Creolization creates a new land before us, and, in this process of creation, it helps us to liberate Columbus from himself.

Édouard GlissantFootnote 1

My feet feel slight pain as I walk barefoot on the bark strips that form the ground of the massive artwork that is Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto’s Nosso Barco Tambor Terra (‘Our Ship Drum Earth’, hereafter NBTT). The tactile irritation is the only discomfort my five senses encounter while inside the piece, an installation hosted at the Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia (Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology; MAAT) from 30 April to 7 October 2024, in Lisbon, Portugal. The piece is visually stunning, formed by the knitting of multi-colour chintz (chita), a spun cotton commonly used in Brazil. The webs outline the external shape and internal design of a ship, though some imagination is required to discern the form of the caravel (caravela) associated with early Portuguese colonialism that is meant to be evoked. Pillared by ornately designed vertical trunks that extend from the floor to the ceiling and recall trees, the ship also holds sacks of dry foods – rice, beans, and corn – as well as fragrant sacks of spices hanging from its ceiling that make walking around it a variegated olfactory experience. The work is meant to be walked through, sat in, lounged in, smelled, and above all sounded, as participants are invited to play the percussion instruments that hang from its ceiling or are connected like tree roots on the ground (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

As an ethnomusicologist, I take some pride in identifying many of the instruments that form the piece (seen in Figure 1) – surdos, repiques, and agogôs from Brazilian samba; European timpani; Portuguese rural adufes (frame drum); Indian tabla – yet many others I could not initially place. The work is, at its title implies, at once a ship – our ship (nosso barco) – something imagined to be in motion; and it is a world – a drum earth (tambor terra) – a planetary geography of human existence mapped through percussion instruments. The soundscape emerging from the ship is often an uncoordinated but pleasant cacophony that reverberates around the atrium. Beyond the aleatoric experimentation of visitors, however, the ship was also ‘played’ during its exhibition at higher levels of coordination at several events, acting as host for varied percussion-based musical practices that primarily reflected the diverse musical communities residing in Lisbon. These events generally manifested a musical lusofonia – that is, musical expressions of communities hailing from or descending from Portuguese-speaking areas around the world – as many of Lisbon’s immigrant and post-migrant communities have come to Lisbon through postcolonial immigration networks. Groups from Portugal, Brazil, Cape Verde, and Guinea-Bissau performed in the ship, often blending rhythms and creating Lusophone musical fusions. Yet, this ship, containing the world, also provided a stage to musicians from or playing the music of Morocco, Cuba, India, Afghanistan, among others.

In taking the form of a caravel carrying spices, foods, drums, and other items that circulated due to colonialism, Neto’s work spotlights Portugal as Europe’s oldest and longest-lasting colonizing country. He scrutinizes its role in the creation of a ‘Europe of which Portugal was the harbinger’,Footnote 2 and by extension of a modern world of exchange and circulation; as sung in its National Anthem, Portugal is the country of ‘Heroes of the Sea … who gave new worlds to the world’. In highlighting the Lusophone world within a more global soundscape through instruments and performances, the work plays on a tension between a particularity and universality of colonial and postcolonial experience. Neto’s ship is an invitation to critically rethink, or, more appropriately in his terminologies, to re-embody or re-experience, hegemonic narratives of coloniality. I understand it as a decolonial critique of occidentalism, which Latin American decolonial scholars have portrayed as the collection of ‘philosophical, political, and cultural paradigms that emerge from and are imbedded in the historical phenomenon of European colonization’.Footnote 3 In his artistic discourse, Neto rejects what he views as occidentalism’s attendant dualisms: the division between nature and culture, colonizer and colonized, performer and audience, subject and object, vision and aurality. The work is a critique not only of the moment ships departed from the Tagus ‘and the world changed forever’,Footnote 4 but of an entire Western episteme that Neto views as having emerged contemporaneously, connecting the Renaissance to the ‘Age of Discoveries’.

For all this past orientation, I argue that the performance events reinforce the fundamentally futurist orientation of the work. Just as performance enacts the future, a ship, Neto told me, ‘always points to the future, but navigates in the present’.Footnote 5 In his various speeches and interviews surrounding the artwork, he asked, ‘Where do we want to go in this drum ship earth of ours?’ I interpret this provocative question as implying a series of other questions: Who as a species do we want to become in the postcolonial future? What are the possibilities for collaboration among the fragments left by the legacies of empire?

For Paul Gilroy, conviviality after empire refers to the ‘processes of cohabitation and interaction that have made multiculture an ordinary feature of social life in Britain’s urban areas and in postcolonial cities elsewhere’. He urges readers to discover in ‘Britain’s spontaneous convivial culture’ ‘a new value in its ability to live with alterity without becoming anxious, fearful, or violent’.Footnote 6 In my forthcoming book, I draw on Gilroy’s notion to argue that Brazilian music in Portugal is conditioned by postcolonial intimacy, an affective context of familiarity that is predicated on the countries’ postcolonial relationship, shared language, and history of circulation of people, material culture, and musical expressions,Footnote 7 and I suggest that postcolonial intimacy can have liberatory as well as reactionary expressions. By creating a space for experimenting with the possible fusions of global percussion emanating from the postcolonial present, Neto’s ship is meant to enact such convivial and intimate but also critical possibilities that arise from colonialism in the Portuguese ex-metropole. I furthermore view the musicking of the work as decolonial in intent, understanding ‘decoloniality’ as a form of praxis, through Bacchetta and Maesa-Cohen’s view of the term as ‘undoing [coloniality], and undoing [that] also opens a space for a different kind of doing’.Footnote 8

In other words, I argue in this article that Neto proposes intimate conviviality as a foundation for critique of the occidentalist, colonial past and the enactment of sensory regimes of a future decolonized world. I consider the musicking that occurred inside the ship as encompassing a series of convivial performative instantiations of the work’s decolonial possibilities. These acts performed specifically in Lisbon, the historical metropole of the Lusophone world, intervened upon the central myths of Portuguese coloniality. In centring performance, rather than solely representation and the provenance of objects, they formed an innovative part of a broader decolonial turn in the curatorial strategies of Portugal’s elite art institutions in a European context in which calls to decolonize the museum have grown ever louder. Over the course of the exhibition, the ship accumulated the meanings of performers’ and visitors’ imaginations of decolonial futures, making the artwork a fundamentally shared project rather than solely the product of Neto’s vision. The collaborative structure of the work allowed the invited musicians and the public to collectively assert their own distinct responses to these questions. All-female ensembles who were invited to perform, for example, notably brought to the fore the issue of female exclusion in percussion and popular music in general, highlighting the role of gender oppression in colonial histories, which had not been prominent in the ship’s initial philosophical design.

In what follows, I explain the colonial symbolism of the location in which the ship was stationed, discuss the philosophical design of the artwork, and examine in detail the performance events that occurred during its exhibition Figure 2. The article is based on interviews with Neto and others, attendance at and participation in the public musical events, and my experience as an ethnomusicologist of Brazilian and Portuguese music, having conducted research about the carnivals of Rio de Janeiro and Lisbon.Footnote 9

Figure 2. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

Belem, ships, and legacies of the Portuguese colonial empire

I was walking along the Tagus River, and, suddenly, I looked ahead and saw nothing. And I realized that there was the Atlantic. Then I looked to the side and imagined all those caravels coming out of the bowels of Europe. I felt this desire to discover things, this absurd curiosity, this energy … But I also [felt] a voracity, a voracity that began to eat the Earth, because this spirit has spread across all the geographies of the world.Footnote 10

This contradictory duality of colonial exploration that Neto describes emanating from his first physical presence on Lisbon’s River Tagus in 2018 – curiosity combined with exploitation – would be central to the conception of NBTT. The exchanges brought about by Portuguese colonialism became key to the formation of new hybridities that may ultimately point to alternative futures. No place, therefore, would be better to undertake such a project questioning these legacies than Lisbon’s Belem neighbourhood where the MAAT overlooks the River Tagus. Belem, Elsa Peralta argues, is ‘the most paradigmatic case of inscription and condensation in the national public space of a memory alluding to the Portuguese colonial empire … housing a memory complex’.Footnote 11 Belem’s riverfront is the site of Vasco da Gama’s departure, which resulted in the navigation of a sea route to India, and thus the beginning of Portugal’s empire in Asia. It has long held a significant place in the colonial imagination of the Portuguese collective memory as a space of origin for the Portuguese ‘Golden Age’ precipitated by what are known in popular discourse as the ‘Discoveries’.

It was only in the later nineteenth century, however, long after Portugal had lost most of its eastern empire and many decades after having lost Brazil in 1822, that governmental and cultural actors engaged in a series of ‘monumentalization actions’Footnote 12 to transform Belem into the pre-eminent site for the glorification of empire. These colonial memories beginning three centuries earlier served as an inspiration for Portugal’s later imperial exploits, as it expanded colonial control of Angola and Mozambique amid the European ‘Scramble for Africa’ (gaining steam following the Berlin Conference in 1884) to regain an international foothold after the country had become a peripheral power within Europe. Buildings associated with the ‘Age of Discoveries’ were renovated, grand urban spaces were built with names such as ‘Empire Square’ (Praça do Império), and others commemorating the navigators were constructed. Colonial gardens featuring vegetation from the colonies were designed, and the official residence of the president was established, making Belem a place of memory as well as the country’s central site of political power. Several museums supporting colonial memorialization were founded or considered, including naval, colonial, and ethnology museums.

The Estado Novo authoritarian state (1933–74), led primarily by the dictatorship of António Oliveira de Salazar, retrenched past colonial nostalgia as a foundation for contemporary imperial exploits. In 1940, Belem held the Portuguese World Exhibition, which attracted three million people to visit pavilions highlighting its colonial possessions. In the 1950s, Portugal appropriated an ideological framework that had been articulated by Brazilian anthropologist Gilberto Freyre in the 1930s, known as lusotropicalismo. The theory offered an apologetics for Portuguese colonization in Brazil, extolling the supposed tolerance of the colonial Portuguese whose willingness to mix with the native populations and Afro-descendent enslaved populations promoted a supposed social intimacy and lack of racism in Brazil, or a ‘racial democracy’. Lusotropicalismo became key to Portugal’s defence of its colonial holdings as essentially beneficent, non-racist, and tolerant, while the rest of Europe began to decolonize. The Portuguese revolution, which was launched by a military coup on 25 April 1974, and was marshalled by officers fed up with Portugal’s bloody colonial wars in Africa, led directly to political decolonization of the African colonies in 1975.

In the fifty years since the revolution, Portugal has sat uneasily with its colonial history. The country has largely sought to resituate its place in the world, and more specifically in Europe as it joined the EU in 1986, by engaging in the postcolonial diplomacy of lusofonia. Based on the ‘shared’ Portuguese language between countries and communities spanning the globe, lusofonia has been a framework for dialogue within the postcolonial world and, since 1996, the Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries. At Lisbon’s 1998 Expo, Portugal’s obsession with its maritime history within this new configuration was on display in its theme of ‘The Oceans, a Heritage for the Future’, commemorating 500 years of the Portuguese ‘Discoveries’. Anthropologist Tim Sieber writes,

Amidst all the seeming representation of multicultural, international, including lusophone, cultural expression in the Lisbon festivities, Portuguese culture itself was implicitly presented as homogeneous, traditional, fairly static, fundamentally European, and white – in sum, sharply distinct from … lusophone forms the Portuguese themselves supposedly spawned.Footnote 13

Such instantiations of lusofonia have been critiqued by Sieber and others as neo-imperialist, neo-lusotropicalista exercises that put Portugal at the centre of mediating between its postcolonial partners. In Belem, the decades following the revolution witnessed a similarly sanitized memorialization of colonialism as a historical facilitation of exchange, communication, and cosmopolitanism. ‘Commodify[ing] the national past, at the expense of the deflation of its ideological context’,Footnote 14 Peralta writes, Belem became a site for both the pedagogical extolling of Portugal’s greatness and tourist consumption. New museums were founded, such as Centro Cultural de Belem in 1988 managed by the Discoveries Foundation, that supported these postcolonial cosmopolitan aspirations. As recently as 2017, the building of a long-in-the-works Museum for the Discoveries has been proposed.

Yet this sanitized framing of ‘Discovery’ has come more heavily under public critique by activists and scholars in Portugal who have reframed the ‘Discoveries’ as the ‘Expansion’ (Expansão), and the museum as originally conceived has not moved forward. In an ‘international scenario of growing ideological polarization around identity politics’, alternative narratives, performances, and exhibitions have proliferated in Belem, and Lisbon more widely, for the ‘contestation and articulation of countermemories’.Footnote 15 In a public letter opposing the Museum of the Discoveries, the signatories called for a new museum reflecting the ‘problematic richness’ of Portugal’s colonial history. While not exclusively devoted to this goal, MAAT has curated several works that mark a decolonial turn in the ‘curating of legacies of colonialism’ in Portugal.Footnote 16 The reflection on the ‘problematic richness’ of Portuguese colonialism is an excellent encapsulation for the provocations expressed in NBTT, which clearly disrupt Belem’s triumphalist symbolism of colonial memory by taking the form of one of the country’s most treasured symbols: the ship.

For any lisboeta, the image of the caravel, which proliferates throughout Lisbon, is a metonym of the entirety of this colonial history and imperial mythmaking. Portugal’s stylized sidewalks feature elaborate portraits of the ship through the arrangement of black and white stones. Belem’s Monument to the Discoveries, built in 1960, takes the form of the caravel bow, jutting into the air with Prince Henry the Navigator, who commissioned Portugal’s early explorations in the fifteenth century, at the top, holding a miniature caravel – a ship within a ship (Figure 3). Apartheid South Africa, which supported Portugal’s domination of nearby Mozambique, gifted the Compass Rose Square that lies in front of the monument, with Portugal’s ‘Discoveries’ inscribed in the ground upon a map of the earth, and the monument has often been vandalized for its colonialist aspirations.

Figure 3. The Monument to the Discoveries in Belem.

Indeed, the ship is perhaps the paradigmatic image of Atlantic colonialism more broadly. Paul Gilroy employs the figure of the ship in The Black Atlantic as a ‘chronotope’, a configuration of space and time that disrupts the boundaries of borders and territories, as he calls attention to the Atlantic as space of circulation: ‘The image of the ship – a living, micro-cultural, micro-political system in motion … focus[es] attention on the middle passage, on the various projects of return to Africa, on the circulation of ideas and activists as well as the movement of key cultural and political artifacts.’Footnote 17 Through the ship, Gilroy reconceptualizes the Black Atlantic as ‘rhizomatic,’ that is, as created through the encounters caused by circulation between the continents of products and exploited Black bodies. But the ship also became a site of Black agency, pan-African connection, and Black mobility, a ‘countercultural of modernity’ for the creation of alternative futures. Historians Linebaugh and Rediker similarly depict the figure of the ship as expressing the ‘machine of commerce’ and the ‘engine of empire’Footnote 18 but also as forging the ‘first place where working people from different continents communicated’.Footnote 19

In a book theorizing the Lusophone ‘Brown Atlantic’ – brown due to its heightened racial mixing – Portuguese anthropologist Miguel Vale de Almeida plays on Gilroy’s archetype of the sailor, noting the ubiquity of sailors in the folklore of the Afro-Brazilian-dominant state of Bahia where the sailor is usually depicted as a white Portuguese man. Yet, like Neto, he provocatively asks if ‘this traveling Sailor … might be a symbol of the reformulation (or should I say inversion?) of the images of ships, sailors, and navigations that saturate the Portuguese national(-ist) imagery? Could he be a symbol of other ways of thinking identities and emancipatory movements?’Footnote 20 Similarly, Neto plays on such classic nautical images and references in order to question the possibilities for these legacies to be resignified and transformed for decolonial futures.

Arte contemporosa: the design of Nosso Barco Tambor Terra

[Arte contemporosa] wants to go beyond the surface, beyond the smooth, the signifier and the signified; it wants to be inside the body, uniting the physical, mental, spiritual and ancestral body; it wants transparency and materiality, union of the diverse; it is naturally relational, symbiotic, mutualistic, multinatural. It believes in the wisdom of the fingers, wants to touch and be touched, exchange, feel through the pores.Footnote 21

On a wall surrounding NBTT at MAAT is written a manifesto of what Neto calls arte contemporosa, a neologism that combines contemporary art with the porous – that is, a contemporary art that is tactile and sensory. He traces his lineage as a sculptor within the revolutionary transformations in the plastic arts that occurred in the twentieth century, citing precedents that promoted abstract conceptualization as embodied in the physical artwork. He designates his ‘school’ as Brazilian neoconcretismo ‘with objectivity and subjectivity walking together through interactivity’, building on the work of Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, and Hélio Oiticica.Footnote 22 Many of his sculptures are large and immersive labyrinths that provoke multiple senses, and they have been featured in the museums of five continents, including the Venice Biennial.

NBTT is Neto’s largest installation to date. Visually, the artwork evokes images of a ship with elements recalling sails, canvas, and ropes. Its woven webs feature coloured flowers and plants, which were cut and crocheted at Neto’s studio, appropriately named the atelienave (Workship). Many of his sculptures explore weights and counterweights, and in NBTT these are provided through some of the key commodities that circulated in the colonial market: sacks containing foods, such as corn, chickpeas, beans, rice, as well as spices such as cinnamon and clove, because, as he told me, ‘Spices were the motivation for these great navigations’. These ‘dry smells’ are one of many sensory elements that make the artwork immersive, ‘entering and touching our bodies’, as the artist described, and providing affective, embodied experiences that manifest the work’s conceptual framework. His work is a rejection of what he called ‘that do not touch’ of most exhibited art (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

Figure 5. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

Neto’s manifesto for arte contemporosa connects this tactile art to a critique of an implied Western episteme: ‘[Arte contemporosa] is suspicious of cultures that think they are superior to nature, for nature is also us; it respects weaknesses, exposes tensions, but respects limits, wants to touch the world with care, attention and love’.Footnote 23 He establishes an aesthetic discourse that at times essentializes particular conceptions of the West and its Others but that provide a performative framework for his intervention on colonialist symbolisms in order to recover the knowledge of colonized peoples and nature. Such essentialist dualisms provide a powerful discursive strategy for Neto’s critique, yet an unresolved tension in the work rests in his valorization of non-Western others in ways that perhaps leave the West vs the Rest binary intact. At other times, he argues against dualism, while markers of the West are not wholly rejected but are rather decentred and recontextualized in horizontal dialogue with those of non-Western others. This at times contradictory tension is reminiscent of other ways that Neto works with material at hand, resignifying, for example, lusotropicalist notions of racial mixture as powerful foundations for musical and social transformation. It is perhaps not the artist’s goal to provide a unified and coherent philosophical statement but rather to ruminate in provocative ways about the possibilities that arise directly from the legacies of colonialism, as problematic as they may be.

In this sense, I understand his arte contemporosa as broadly a performative critique of occidentalism, a framework which decolonial scholars have suggested links the transformations of modernity wrought in the Renaissance to the contemporaneous projects of colonialism. Through colonialism, occidentalism became, as Walter Mignolo writes, ‘the overarching geopolitical imaginary of the modern/colonial world system’.Footnote 24 Similarly, for Neto, colonialism was not only a political transformation, but also an epistemological one in both metropole and colony:

Portuguese colonization generated a production of gigantic wealth that fed the entire European intellectual structure. This entire process of intellectualization, rationalization, mathematics, science and so on, took place due to the financial support that came from all these colonies. Gold from Brazil went straight to London to support the Industrial Revolution.

For Neto, the divisions of self and other created through the colonial stipulation of the West and the Rest are linked to the attendant dualisms of subject and object, body and mind, and culture and nature. He understands these binaries as having been expressed during the Renaissance through the development of perspectivism in the visual arts: ‘because of perspective, the society we live in today is the society of objectivity … and this rationalism produces a social organization based around productivity’. Perspectivism, he argues, is an artistic manifestation of humanity as distinct from that which it observes, resulting in the ‘distancing of people from the earth … We became the beings of culture, the beings of the object and rationalism.’ According to the artist, this process resulted in the ‘disenchantment of European people’ from nature to dominate it, and a distancing from a multi-sensorial mode of knowing the world present in other cultural epistemologies.

In these terms, traditional Western sculpture, which exteriorizes art as an object to be perceived, similarly separates the viewing subject from an object. By contrast, an immersive, non-dualist approach to sculpture aims to ‘create a calming serenity between body and culture, body and nature, a continuity between us and the body of the Earth’. Neto’s rejection of perspectivism implies a resignification of the object in relation to the subject, as written in the manifesto: ‘[Arte contemporosa] also uses objects, but it knows that they are the striking expression of human beings, and it knows that they, despite their artificiality, are also nature’.Footnote 25 Through the multi-sensorial and interactive design of Neto’s art, objects enter into a visceral relationality with the embodied subject. Claiming that ‘perspective is the triumph of vision’, Neto troubles the modern pre-eminence of vision in Western culture through his multi-sensory work in the traditionally visual field of sculpture. Indeed, cultural theorists have argued that hegemonic narratives of modernity rely on a separation of vision from sound and other senses, and an elevation of vision as the highest epistemological sense. Jonathan Sterne, for example, challenges the notion that ‘in becoming modern, Western culture moved away from a culture of hearing to a culture of seeing’ by showing how sound itself became an object of scientific knowledge.Footnote 26 Notably, Sterne connects the development of modern notions of sound and vision to colonialism as well: ‘Capitalism, rationalism, science, colonialism, and a host of other factors – the “maelstrom” of modernity … all affected constructs and practices of sound, hearing, and listening.’Footnote 27 The narratives of modernity regarding the pre-eminence of vision became based, Sterne argues, on the cultural myths of the ‘audiovisual litany’, including the dichotomies that ‘hearing is concerned with interiors, vision is concerned with surfaces’; ‘hearing is about affect, vision is about intellect’; ‘hearing is a sense that immerses us in the world, vision is a sense that removes us from it’.Footnote 28 As Sterne rewrites the history of modernity with sound as its object, Neto similarly destabilizes narratives about both sensorial fields and puts them in dynamic engagement with one another.

Neto’s anti-dualism is also a rejection of culture as a mark of absolute difference between human communities and a proposal instead of relationality and interaction, as the manifesto continues:

[Arte contemporosa] is a friend of the boa constrictor, the snake and the cundaline; it knows that light vibrates in waves as well as in packets of energy and that the two things are not exclusive; on the contrary, they are complementary, yin and yang, at the same time. It studies the continuity between bodies, between mind, hand and earth, sees planet earth as a body, not as a landscape; it sees itself as part of the earth’s body, as well as part of the entire universe, or would it be better to say the entire multiverse?Footnote 29

As in the manifesto, particular cultural differences are referenced throughout the work. Boa constrictors, for example, are embodied in the snaking chintz that outlines the ship, as ‘the serpent in certain South American indigenous cultures is our mother’. But these particular references are given meaning primarily in their interaction with others.

In this celebration of mixture, Neto brings forth his own identity as a Brazilian in the artwork. Working through conventional languages in order to subvert them, he draws on well-known tropes of Brazilian cultural exceptionalism rooted in lusotropicalismo, while refusing to erase the violence inherent in this mixture. He puts himself in the lineage of the Brazilian avant-garde, whose foundational concept of antropofagia (cannibalism) valorized indigenous Brazilian agency to ‘eat’ the rest of the world, digest it, and mix it up, producing a result that is fundamentally Brazilian and hybridized. He distinguished Brazil’s history of mestiçagem (racial mixture) from the ‘one-drop rule’ of racial identity in the United States, arguing that the United States represented the ‘extreme Occident’ – ‘those who separate and classify the most and are against the idea of mixing’. Linking this reflection to sculpture, he relates that he ‘saw in Europe and in the United States that the separation between figure and background is very clear. The figure and the background don’t mix, whereas, here in Brazil, it’s a forest, and anything can happen.’ This celebration of hybidrity relates to his own ambivalent relationship to the West. Growing up in Brazil, he described, was a process of postcolonial enculturation as a Westerner, yet, as he has toured the world, he has often been interpellated as a non-Westerner. Switching to English, he recounted, ‘What I understood is that we are not Western, because we are not peer, we are poor … For me, it’s a relief not to be Western, plagued by the problems of structures of separation, classification, and separation’.

The four words of the NBTT’s title, ‘our ship drum earth’, are distinct references that similarly collapse into one another, every term signifying every other. The ship contains percussion instruments from around the world, acting as a vehicle through which these items and the performative cultures to which they are associated circulated. The ship is a drum to be entered and played, and it is also the world, ‘our world’. Similarly connecting the local to the global, Gilroy argues that, ‘If conviviality helps to fix that primary local pole of this interpretative exercise, the other extreme can be approached via the idea of “planetarity”’, which ‘suggests both contingency and movement’.Footnote 30 Our ship drum earth remaps the world through its display of percussion, with the interior of the ship holding several knit trunks that arise from the ground like trees to the top representing world areas (Figure 6). With African drums woven into the central trunk, the continent acts as the ship drum earth’s central core, ‘the place of origin for us all’, as Neto relates, out from which the other trunks radiate. South American instruments appear to the southwest, while European instruments appear at the northwest and far west. Asian instruments, particularly from India and Thailand, appear east of the African core. These musical synecdoches of postcolonial others gain a central protagonism in NBTT, and the remapping ‘provincializes Europe’ by highlighting Africa and its percussive traditions and leaving Europe to is extremities.Footnote 31 Neto valorizes the ‘Others of Western music’, those instruments and traditions that were exteriorized from Western culture by orientalism.Footnote 32 By placing African percussion at the centre, the piece simultaneously risks essentializing Africa with percussion and rhythm, reflecting the ways that the ship often reasserts conventional binaries at the same time as it seeks to undercut them.

Figure 6. Mapping of ship world through drum placement by Neto.

Though Neto originally conceived of the piece as highlighting distinct continents, eventually a more organic conception evolved. He described how his idea for this mapping was partly inspired by the anti-colonial notion of ‘archipelago-places’ of Caribbean postcolonial theorist Édouard Glissant, who writes of ‘such a concept of the Relative, of the open links with the Other, of what I call a Poétique de la Relation, [which] shades or moderates the splendid and triumphant voice of what I call Continental thinking, the thought of systems’.Footnote 33 This cultural relativity is the expression of creolization, which, for Glissant, is ‘the product of this synthesis’ and ‘a new kind of expression, a supplement to the two (or more) original roots, or series of roots’.Footnote 34 The theorist argues that, unlike European settlers in the Americas, who brought with them ‘preserved folklore’, Afro-descendant communities worked with cultural ‘traces’, which were combined with other elements. This rhizomatic expression of créolité is a ‘lived experience’, a ‘present-day goal’, and a future-oriented ‘utopian ideal’ of solidarityFootnote 35 that may forge ‘future Americas that are at last and for the first time both deeply unified and truly diversified’.Footnote 36 In NBTT, the continental boundaries between the clusters are likewise ill defined, propitiating the creolized sonic and cultural mixing that Neto proposes as a performative futurity, as he recounted: ‘We have drums from all over the world. Drums from Thailand are different from drums from Africa and drums from Brazil, but they are still drums. It’s not always easy to pick up the Japanese way of playing a taiko drum because culturally it’s very different from us. But this conversation is viable.’

A crucial partner in the curation of the percussion instruments was the Lisbon-based Portuguese percussionist Tânia Lopes, whose own musical background had involved several intercultural projects based on percussion. In my interview with her, she recounted her musical formation as arising from her participation in orquestras de percussão, neo-folkloric percussion ensembles that have exploded in popularity in Portugal in the last three decades based on creative combinations of Portuguese percussive traditions.Footnote 37 She studied with Uruguayan percussionist Santiago Vázquez, whose ensemble Bomba del Tiempo in Buenos Aires works through a series of hand signals that fuse global percussion traditions through improvisation. As musical lusofonia became an increasingly popular frame for performance in Portugal in the past decades, much of her work has involved intercultural collaboration with Afro-descendent percussion traditions from the Lusophone world, such as a project that mixed Portuguese carnival characters with Brazilian percussion and afro-mandingo from Guinea-Bissau. Yet, in these collaborations, she has sought to work in a more horizontal manner than Sieber’s critique of musical lusofonia discussed earlier, akin to what ethnomusicologist Bart Vanspauwen describes as ‘lusofonia as intervention’.Footnote 38 Focusing on hip-hop scenes in Lisbon that bring together musicians descending from various geographies impacted by Portuguese colonialism, Vanspauwen argues that the commonality of postcolonial experience can provide a framework for subaltern collaboration that challenges the coloniality too often reaffirmed in the lusofonia framework. Lopes’s experience of working in Lusophone percussion fusion projects from a critical perspective made her the ideal candidate to collaborate with Neto, as NBTT emerged as a similarly ‘interventive Lusophone’ project, with an initial conception to feature percussion instruments from Portugal and its ex-colonies. Neto enlisted her to collect traditional instruments from Portugal’s ex-colonies in Africa, to which were added several Brazilian instruments in consultation with the artist.

Neto had recently travelled to Thailand from where he brought several percussion instruments, and they decided that these would be added as well. (Incidentally, Belem’s main Empire Square features a pavilion offered by the Thai embassy in homage to 500 years of Luso-Thai ‘friendship’, a memorial to the fact that non-Lusophone geographies have also long been impacted by Portuguese colonialism.) Lopes explained that gradually the concept shifted and that ‘the ship would contain everything’. For Neto, this expansion beyond Lusophone references was a logical extension of the artwork, playing on the protagonism of Portugal as the origin of lusofonia and the resultant globalized world:

Lusofonia was perhaps the first strong manifestation of this macro expansion of the West, but I didn’t want to be limited to lusofonia … This issue of navigation from Portugal really had a huge impact on me when I was there. But I’m also a guy who’s traveling all over the world … The world is bigger than lusofonia, though lusofonia is also a planetary manifestation.

Indeed, it is through this tension between the particularity of lusofonia and the universality of globalization, seen in Figure 7 in Neto’s own playing of a surdo accompanied by talba, that he seeks to ask the question of where we, humanity, want to travel in this ship drum earth of ours, going beyond a circumscribed narration of Portuguese colonialism and its impacts.

Figure 7. Ernesto Neto (left) playing surdo accompanying Francisco Cabral on tabla. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

In addition to musical mixing, Neto also valorizes Brazil for its spirit of musical participation, as expressed in the manifesto: ‘Arte contemporosa sees itself as loving, praising the vibrant strength of the drum, caxixi, flute, guitar, maraca, in singing, learning from childhood that joy is healing. It values social balance; no one is greater than nature just as no one is greater than anyone else; we all have our contribution to make’.Footnote 39 The artist has in recent years been involved in learning percussion himself through his participation in the oficina of the bateria (percussion group) Balança, mas não cai (It Swings but Doesn’t Fall Apart), which teaches samba and other Brazilian percussion traditions. Oficinas are participatory classes with a generally low cost of entry dedicated to the study of particular musical traditions or instruments. Many are run by blocos, or carnival parading ensembles, whose oficinas provide the point of entry to participate in carnival.

Neto’s celebration of participatory music is reminiscent of ethnomusicologist Thomas Turino’s distinction between presentational and participatory ‘fields of music making’. For Turino, ‘the participatory field is radical within the capitalist cosmopolitan formation in that it is not for listening apart from doing … Participatory performance is radical in that it hinders professionalism, control, and the creation of commodity forms’.Footnote 40 Western society, Neto argues, is dominated by the ‘relationship of stage/audience’, akin to what Turino has called the ‘presentational’ field. Neto valorizes the origins of Brazilian music in the Afro-descendent roda, a circular form a music-making that is the basis of many other Afro-Brazilian and contemporary popular genres. In a roda de samba, he relates, ‘The musicians surround a table, but around them there are a lot of people playing this, playing that, drumming and everyone dancing around … The idea is to include and not exclude.’ Through interaction with NBTT, Neto urges a reclamation of what he frames as Western society’s repression of musical expression and division of performers and spectators. Elsewhere, I have critiqued Turino’s model of participation for its reification of formalist binaries between musical cultures. In the case of Brazil, I argue that musical practices often evade the distinctions Turino makes between presentational and participatory performance. Yet I suggest there that musical participation is a value that provides a performative foundation for the enactment of inclusion, as we see in Neto’s statements as well.Footnote 41

In NBTT, Neto extends the participatory ethic in a post-human (or pre-human) direction, offering in the manifesto the ship as an intervention in the human relationship with the earth itself:

Our Ship Humanity Planet Earth needs everyone: insects, bees, plants, trees, animals, fungi, lichens, bacteria … as in drumming we all need to be together, at the same time, Umbuntu, neither in front nor behind. There is space for everyone to have their individual expression, but between the beginning and end of each cycle we all have to be together so that the balance and illumination of all give space for the shine, trance and well-being of each being.Footnote 42

For Neto, the drum emblematizes the union of culture and nature, a human construction based on the vegetable body and animal skin. NBTT is an expression of a participatory, cosmic environmentalism, in which we must treat the earth well, because the planet is an extension of our own body. Neto cites in the manifesto the Bantu philosophical concept of umbuntu, often translated as ‘I am because you are’, or, as he translates it, ‘being together – we all know how to dance and sing’.Footnote 43

During the months the work was exhibited, it provided a space of musical participation for visitors to enter and experiment with the diverse percussion instruments (Figure 8). On a given visit, the beats emanating from the boat were sounded by the random collection of visitors there at any one time. I visited several times, finding different ways to play the instruments, while my then four-year-old daughter ran around the ship in delight testing the sound and feel of each one. Visitors rarely experimented in isolation but were rather joined by others, whose collective musical action resulted in a relatively uncoordinated soundscape. Though neither Neto nor Lopes cited John Cage as an inspiration, the music emerging from the boat was reminiscent of aleatoric composition in which some element of the composition is left to chance. Lopes described the ship’s shifting soundscape:

The sound begins very softly, disappears, suddenly very loud and then drops. There are those who stay very quiet listening; there are those who listen and play even louder; there are those who don’t listen and just play. It’s always on the move. I don’t often see people playing together, but I do see individuality expressed, some people with hands hidden playing lightly, calmly, very softly; others arriving awkwardly and playing with force … But I’ve also experienced moments of listening to a sound and starting to hear little things being added, as if the visitors were building a theme without knowing that they were building something together.

Figure 8. Visitors playing instruments. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

For Neto, the musical expression emanating from the ship is akin to the emergence of creole languages, those which function within multiple linguistic systems but constitute new communicative systems. Glissant argues that these languages are based on ‘forgetting, that is to say, integration, of what the language is based upon: the multitude of African languages, on the one hand, and of European languages, on the other’.Footnote 44 Creole languages function through ‘The perpetual need to get around the rule of silence [imposed by colonialism, which] creates a literature that is not naturally continuous, but that bursts forth in fragments’,Footnote 45 yet, for Glissant, this ‘multiculturalism is not disorder’.Footnote 46 Linebaugh and Rediker similarly locate the ship as a crucial space for the creolization of language: ‘European imperialism also created the conditions for the circulation of experience within the huge masses of labor it had set in motion. The circulation of experience depended in part on the fashioning of new languages … [such as] the pidgin English that became in the tumultuous years of the slave trade the essential language of the Atlantic … It was a dialect that arose less from its lexical range than from the musical qualities of stress and pitch.’Footnote 47 Such linguistic-musical creolization was thematized by Neto in the artwork’s own theme song, ‘Tambor Terra’, written by Neto. The lyrics appeared on the wall surrounding the exhibition, and the recording is featured on the exhibition’s webpage on the museum website:Footnote 48

Nosso barco tambor terra

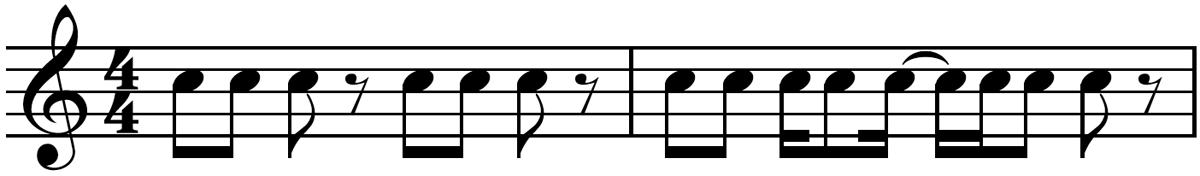

In the first strophe, the song transforms the four words of the artwork’s title, shortening the words and pronouncing them with different accents and intonations marked by the Portuguese diacritics, as if creolized by the diverse speakers who came in contact with the Portuguese language. In the second verse, Neto uses ‘incorrect’ Portuguese common in the Brazilian variant, using the second person plural ‘we’ along with the third person singular ‘go’, to ask the fundamental question of the work: ‘Where are we going?’ In the second instance of the question, it is pronounced in an accent from Rio de Janeiro, shifting from the European Portuguese ‘nós’ to ‘nois’. These transformations are a portrait of linguistic creolization in process. Musically, Neto’s song points to Afro-Brazilian origins, as it is composed as an afoxé, a genre rhythmically based around the ijexá rhythm played on the agogô bell, which is used in the Yoruban-derived Afro-Brazilian religious tradition of Candomblé (Example 1). The bloco Filhos de Gandhi of the Brazilian city of Salvador brought these sacred rhythms into carnival, creating the secular genre of afoxé through which ijexá has since circulated in Brazilian popular music but which maintains a clear reference to Afro-Brazilian origins.

Example 1. Theme song integrating original written melody provided by Neto with lyrics and ijexá rhythm as heard by author in the song as recorded.

NBTT is a manifestation of Neto’s elaborate conceptual design poetically brought to life in his manifesto on arte contemporosa. While he at times reasserts the very binaries he seeks to destabilize elsewhere, he frames arte contemporosa as a critique of the Western/modern/colonial episteme, providing a foundation for the world wrought by colonialism to be transformed towards new futures. But it would be those who visited and experimented with the piece that would further set these alternative paths in motion, especially in the performance events to which this article now turns.

Decolonial musicking in ‘Our Ship Drum Earth’

Though the sculpture stood primarily as an invitation for haphazard musicking, the ship also acted as an immersive stage for musical performances and lecture-demonstrations. It was also itself ‘played’ by professional musicians who performed on the sculpture’s instruments, transforming it into a percussion orchestra. These events were curated primarily by Lopes, who was on site for the duration of the exposition, while Neto was present at the opening and closing but otherwise resided in Rio de Janeiro. Working with her numerous contacts of musicians and percussion groups throughout the Lisbon area, she provided a space of protagonism for immigrants, students, and others for whom performing in a noted museum was not necessarily a norm. Over the course of the installation, the ship accumulated meanings arising from these collaborative performances, which generated responses to Neto’s provocative question of ‘where’ to take the vessel.

Most of the performers hailed from Portugal’s ex-colonies and Portugal, reflecting the dynamics of postcolonial migration in which the movement of communities from ex-colonies to ex-metropole is facilitated by common language, cultural references, and diplomatic accords. Much of this postcolonial migration was first based on labour migration from the former African colonies, which increased markedly after the country’s independence in 1975 especially to the Lisbon area, while Brazilian migration emerged in the 1990s, making Brazilians now the largest immigrant group in the country. Neto explained that the performances ‘were totally linked to lusofonia because this is the material we had at hand’. Yet, similarly to how the percussion instruments displayed were connected especially to the Lusophone world but moved beyond it to a more planetary representativity, Lopes took care to feature other musicians and communities whose residence in Lisbon is determined not by direct postcolonial links to Portugal but to other, more recent migratory patterns that reach beyond it. The rest of the article discusses the opening, which installed the ship in Lisbon; the lecture-demonstrations, which protagonized various immigrant groups to tell their stories through music and narration; and the closing, when the ship ‘set sail’ off to forge new postcolonial futures, fashioned not only by its initial construction but the succession of events during its time in Lisbon.

Opening

The opening on 30 April 2024 featured two separate elements: a concert using the ship’s percussion instruments and a mobile parade departing from the ship and circling its exterior. The concert was led by eight professional percussionists who were either residents of Lisbon or Neto’s percussion teachers from Rio de Janeiro who accompanied the artist to Lisbon for the occasion. I was a musical participant in the exhibition’s opening, which allowed me to follow the planning for the event, having been invited to play with Lisbon’s Brazilian carnival bloco Bué Tolo, an ensemble based on samba school percussion that plays a variety of genres and with which I play trumpet.

In a pre-performance pep talk, Neto lauded these percussionists as exponents of the mysteries of the ‘multicultural percussion traditions living here in Portugal, a country that created a huge mess (bagunça) around the world; but, at least through percussion, we are able to dialogue’. Then the musicians descended to the ship. Their performance was framed around the repetition of a paradinha, or a rhythmic break derived from the call and response practices of Rio’s samba schools in which the lead repique drum plays a rhythm after which the bateria (percussion ensemble) responds with the same rhythm (Example 2). The piece took the form of what could be called (but the musicians did not) a rotating ‘concerto’, with the paradinha taking the function of a ‘ritornello’ (also my term) between which different solo instruments were featured, which subsequently established a groove associated with the instrument that the other musicians accompanied. Since each performer would lead the others along with any visitors who attempted to play along, the function of this ritornello would be to calm the inevitable chaos that might ensue as well as to transition from one performer to another.

Example 2. Repique-derived paradinha/‘ritornello’.

The performance began with four renditions of this rhythm led by the repique. Portuguese percussionist André Soares, who has extensively studied the percussion traditions of the Portuguese ex-colony Guinea-Bissau, then began a solo groove on the West African dunun drums to which the other percussionist gradually added, creating an improvised, polyrhythmic texture. This beginning of the concert on West African percussion marked a performative statement consistent with the work’s spatial reorganization of the world with Africa at its centre. An agogô bell interrupted the groove with the call and response ritornello, and suddenly a rumbling timpani entered in the far west of the ship with dynamically contrasting unmetred rolls giving way to a more stridently marked metre with a musical improvisation based as much on taiko as Western percussion. The performer, Ryoko Imai, is a Japanese percussionist and resident of Lisbon who trained in Western art music as well as taiko and performs in elite orchestras around the world. She eventually played the ritornello, and the attention shifted to the Portuguese percussionist Paulo Charneca, who played a Portuguese bass drum in an improvisation reminiscent of the booming bombos, ensembles of northern Portugal consisting of prominent bass drums accompanied by snares and often bagpipes.

The ritornello again interrupted his groove, as the attention moved to the east of the ship for Francisco Cabral, a Portuguese percussionist who has devoted himself to the study of the North Indian tablas – the subcontinent too was marked by Portuguese colonialism, though direct rule was eventually consolidated primarily in the South Indian state of Goa. He played six tuned tablas in a performance that captured the development structure of Hindustani performance in miniature. Beginning with an unmetred section that highlighted the melodic profile of the percussion, akin to the introductory alap which establishes the rag (melodic mode), he shifted into an eight-beat tal (percussion cycle). In Hindustani music, the tabla generally enters only once the metre is established after the alap, which is interpreted by voice or a melodic instrument not accompanied by percussion, but Cabral creatively adapted this structure by initially using the tabla melodically and without metre. This provided a foundation for an increasingly complex set of rhythmic variations accompanied by the others until the next ritornello shifted to Portuguese percussionist Ricardo Passos playing the Arabic darbuka, just east of the African centre. Similarly beginning with an unmetred introduction akin to the introductory taksim section in Arabic music (which is also generally not played by percussion), he then shifted into the common iqa (rhythmic mode) of maqsum. He was interrupted by a Brazilian repique played by the Brazilian percussionist Manguerinha, who played the paradinha rhythm, which is itself associated with this drum, before launching into a complex samba improvisation, eventually shifting into a samba groove led by the three percussionists from Rio de Janeiro. The entire ‘concerto form’ could be summarized as: Paradinha/Ritornello, Dunun (Guinea-Bissau), Ritornello, Timpani (Western Art Music), Ritornello, Bombo (Portuguese percussion), Ritornello, Tabla (India), Ritornello, Darbuka (Middle East), Ritornello, Samba (Brazil).

Manguerinha interrupted the musicians again, shifting into afoxé, which offered first an invitation to the audience to accompany the musicians and then provided the shift to the second part of the event, marked by the musicians leading the audience in singing the work’s theme song. I emerged with Bué Tolo, and we began to play the song on the horns, amplifying the voices, as we led the visitors out of the ship and then to circle around it, engaging in what Neto framed as a ritual collective blessing (Figure 9).Footnote 49

Figure 9. Opening parade showing author on left playing trumpet. Photo by Luís Barra, 2024. Image credit: MAAT.

From a melodic perspective, our playing of the theme song was the most planned element by the curators. At the first rehearsal two days before the opening, it was obvious to me that the organizers had a clear idea of what the percussion was to do, but the horns were left at the last minute to propose melodies to play over the different rhythms. I unexpectedly played a fundamental role in the opening event as the horn player who chose and coordinated most of the melodic repertoire. We scrambled at the last minute to put together a repertoire that was agreed upon a day before and honed in the museum green room in the hour before the gig. This seemed a fitting reversal of the position in which percussionists are often put to figure out rhythmic accompaniment to harmonic and melodic elements prepared by arrangers. The songs I proposed had to fit the theme of the piece as well as the rhythmic profile and cultural contexts of the rhythms that were to be played. My participant-observation in the opening thus reflected the dialogic, participatory impulse of Neto’s design, as the parade was the result of an exercise in intercultural improvisation resulting in multicultural bricolage. Rather than defining full control over the end result, Neto approached the other musicians involved as co-creative collaborators whose participation was crucial to the realization of the ship’s musical possibilities. My research into these events was a manifestation of an uncertainty principle of much ethnomusicological research that was especially true in this case. It was impossible to study the musicalization of the ship without altering it; the work was a musical Schrodinger’s cat.

The parade groups included Bang Bang percussion, a Lisbon-based group that plays afro-mandinga percussion traditions of Guinea-Bissau, carrying three double-sided drums of difference sizes and pitches; Casa da Pia, a Portuguese neo-folkoric orquestra de percussão of students taught by Lopes, for whom the integration of students was an important element of the work’s participatory invitation; and Bué Tolo, which was invited to the event by the Brazilian teachers of Neto, as the group’s leader had worked in Rio de Janeiro with some of the primary groups of the city’s street carnival. Reflecting a surprise of multi-sited fieldwork, I had played alongside and worked with these musicians during my fieldwork in Rio de Janeiro on street carnival. The parade, instigated as it was by Brazilians who lead multiple carnival ensembles, took on a carnivalesque atmosphere, with one person costumed as an ambulante, a mobile beer seller of Rio’s street carnival. But it retained a sacred element, as each group stopped for the next in a salutation (saudação) for the ship, providing space to play their individual contribution before the other groups began to accompany.

In a fashion similar to the concert portion, each of these groups would lead the others in a rhythm, which would provide a foundation for accompaniment, as the groups had studied each other’s rhythm beforehand. After the performance of the ship’s theme song, Bué Tolo shifted into funk, a rhythm and genre that became popular in Brazil in the 1970s with the Black Rio movement, inspired by the Pan-Africanist politics of American funk (and distinct from the later carioca funk genre). US funk’s embrace in Brazil was implicitly, and sometimes explicitly, a rejection of the conciliatory lusotropicalista ‘myth of racial democracy’ espoused by the military dictatorship of the time. The horns played the melody of ‘Que Beleza’ (What Beauty) by Tim Maia, one of the most visible pop musicians to arise from the movement. The song’s refrain, a buoyant repetition of ‘what beauty’, appeared merely a comment on the artwork’s aesthetic, but the lyrics (here excerpted and translated by the author) in retrospect seemed to provide a deeper reading of the ship:

Que beleza é sentir a natureza

Maia’s portrait of the beauty of recovering the past in a Brazilian Afro-diasporic context of fragmentation of cultural knowledge from Africa seemed unwittingly a fitting commentary on Neto’s own creolized, multi-temporal mythology in which the past, present, and future are all embodied in the ship’s movement towards some new location.

The Iberian Peninsula itself was decentred but not absent, as the students of the orquestra de percussão Casa Pia next played a rhythm (rumba de baixana) from Galicia, a Celtic-identifying region of Spain with many common links to the north of Portugal, over which the horns played a binary melody originally played by bagpipes (gaitas). Bang Bang percussion took over, playing the sofa rhythm of Guinea-Bissau. Lacking musical references from the country, I suggested we play João Donato’s ‘Emoriô’, a Brazilian pop song commonly played in Rio’s street carnival based on the ijexá rhythm, which has a rhythmic profile relatively similar to sofa. The lyrics of the song reflect on the Afro-Brazilian origins of Brazilian culture and its religious pantheon of orixás, and here it was on this occasion accompanied by West African percussion.

The paraders finally arrived in the area to the west of the ship, where the group Finka Pé, composed by women of Cape Verdean descent, was seated and began playing the genre batuku (from the Portuguese batuque, or the act of drumming). The songs are generally accompanied by a polyrhythmic 6/8, or three against two, rhythm, providing a foundation for call and response vocals and dance. The primary percussion instrument of the tradition was allegedly developed in response to the colonial prohibition of playing drums, as the batucadeiras stuffed clothes in bags, which they held between their knees and on which they beat out the rhythm. The group is organized at the association Moinho da Juventude, a cultural organization located in the Cova da Moura neighbourhood of Lisbon. The area is often referred to by the Brazilian term favela due to the informal constructions and marginalized Afro-descendent populations that reside there. Dating from the migratory influxes from Cape Verde and other African countries following the Portuguese revolution, Cova da Moura remains one of the most disenfranchised areas of the city, and Moinho da Juventude provides educational services and cultural activities in the area. Images of Amílcar Cabral, the anti-colonial freedom fighter of Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau likely assassinated by the Portuguese government, are omnipresent in Cova da Moura, and they mark a visual manifestation of the ongoing struggle for independence from Portuguese coloniality. At this performance outside Neto’s ship, this gesture was expressed by two young people who unfurled the Cape Verdean flag to wild applause (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Cape Verdean batuku at the opening.

The event ended with all the percussion groups playing samba together, over which the horns played the refrain of Clara Nunes’s samba, the ‘Canto das três raças’. The song memorializes the ‘three races’ – Indigenous, African, and European – whose violent mixture created Brazil, commemorating the resistant legacies of each one, such as the African maroon communities (quilombolas) and anti-Portuguese independence movements. These histories have created a country in which ‘Every people of this land, when they can sing, sing of pain.’ This expression of suffering shifted to happiness in the final performance of the samba ‘Tristeza’, the lyrics of which implore sadness to depart from the soul and invite joy to return through song. Both songs were well known and the audience sang along, as the emotional movement from pain to joy was meant to capture the ship’s contradictory legacies of past injustices and alternative futures.

Though the concert and parade of this opening had many pre-planned elements, much of it was also left to chance. The improvisations during the concert were accompanied by the sonic chaos of an audience that did not (and were not supposed to) respect conventional high art expectations for silence, while some visitors played along. Much like the ship itself, the performance provided a planned structure to be adapted and transformed through the invitation to participation and spontaneity.

BatuConversas

In contrast to the chaos of the opening, the following events were small and intimate, generally featuring musicians and groups from the various immigrant communities in Lisbon in a series of lecture-demonstrations called ‘BatuConversas’, a neologism that mixed ‘batuque’ with ‘conversation’. At the first BatuConversa, the work’s curator, Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, framed this series as performative incarnations of the concepts embodied in the sculpture, explaining,

The caravels changed the history of humanity forever through colonial and violent processes … but they also changed it in an unpredictable, fertile, living, organic way that allowed encounters that would not have been possible otherwise. And what we have here is a meeting of musicians who come from different places in the world, and each will bring their own stories, their cultures, their ways of seeing the world.

In other words, the BatuConversas provided a stage for the invited immigrant artists to expound on their experiences and respective percussive traditions, allowing for prolonged interventions on the meaning of the artwork that surpassed what had been anticipated by Neto.

The first BatuConversa event was entitled appropriately with the onomatopoeia of samba percussion ‘Bum Bum Paticumbum Prugurundum’. Held two days after the opening, it included many but not all the professional musicians from the opening concert, representing musical cultures of Brazil, Portugal, and North Africa, as well as three other percussionists from Guinea-Bissau, Cuba, and Afghanistan. Keeping with the participatory ethos, throughout the event, the visitors were invited to participate as dancers and percussionists to play the instruments hanging from the ship and experiment with the rhythms the artists introduced. After the musicians introduced themselves and their respective traditions, the visitors were invited to sing the sculpture’s theme song, which had come to feel within a few days to be deeply tied to the artwork through its many iterations.

The Brazilian musicians began the event playing a series of Afro-Brazilian rhythms including ijexá, the rhythm of the theme song, speaking of the importance of musical inclusion in Afro-Brazilian music and religion and connecting these elements to contemporary secular traditions such as the roda de samba and Rio’s samba schools. Osvaldo Pegudo of Cuba similarly spoke of the African foundations of Cuban percussion in santería, the Afro-Cuban syncretic religion of Yoruba origin that emerged somewhat in parallel to Candomblé. He drew links to contemporary genres and carnival traditions in Cuba, involved the visitors in clapping the rhythms, and introduced a series of dances linked to the percussion instruments. Gueladjo Sane, who had performed with the National Ballet of Guinea-Bissau around the world, performed on the country’s dunun trio of drums from Guinea-Bissau and presented various dances of the country. Introducing the wooden idiophone bombolom tied to the African core, he spoke of its communicative power and likened it to a telephone.

While most of the musicians hailed from the Lusophone and/or Afro-diasporic worlds, perhaps the most unexpected participant was Ustad Fazel Sapand of Afghanistan, who introduced the tablas and the drum syllabary of bol. When the Taliban re-conquered Afghanistan in 2021 and re-imposed their interdiction of music, 300 musicians and students were given asylum as refugees in Portugal. Most of these musicians were members of the Afghanistan National Institute of Music, which was founded in 2010 to maintain and develop the country’s classical music traditions related to the Hindustani music of Northern India. The school is notable for its mission to educate girls and women, and its ensembles have toured the world playing at prestigious venues such as New York’s Kennedy Center. On this occasion, describing his transformation from music teacher to refugee while he learnt English, Portuguese and ‘Portinglês’ at the same time, Sapand related how he has maintained his musical practices in Portugal in a variety of fusion projects, currently completing a Master’s in ethnomusicology at Universidade Nova de Lisboa. His inclusion in the event fell well beyond the Lusophone frame and represented the broader multiculturality of Lisbon’s immigrant communities, as well as continuing dynamics of mobility due to Western imperialism beyond Portuguese colonialism. It highlighted Neto’s notion that ‘the world is larger than lusofonia’.

Portuguese percussionist Ricardo Passos presented percussion of the Arabic world, underlining the developmental continuities between frame drums such as the Arabic riqq, the Portuguese adufe and the Brazilian pandeiro linked through the Arabic conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. Drawing on Fazel’s presentation of bol, he explained the drum syllabaries in the Arabic world, sparking a discussion between all the musicians about rhythmic vocalizations around the world, from the highly systematized in India to the informal but omnipresent vocalizations in Brazil. Leaving Portugal for last, as consistent with the sculpture’s anti-Eurocentric design, Lopes presented the Portuguese adufes, associated especially with women’s vocal music from the Beira Baixa region. She made connections between the techniques of playing the alfaia drum in Brazilian maracatu and the Portuguese caixas de rufo, the zabumba drums of Portugal, and the related zabumbas of Brazil. She performed on the Portuguese bombos and explained that the bombo ensembles are also called Zé-Pereiras, the same name as the mythical Portuguese immigrant who is credited for founding Rio de Janeiro’s carnival parading traditions in the nineteenth century. The event ended in a collective jam led by Sane of Guinea-Bissau, embodying the work’s proposal of intercultural musicking with Africa at its centre. Bringing to life the sculpture’s logic of displaying diverse instruments in juxtaposition with one another, the performers took the opportunity to put their individual percussion traditions in broader historical contexts, making transcultural links between them; discussing the circulations of instruments, rhythms, and people around the world; and strengthening the connections that the ship’s mobility made possible.

These initial events had featured predominantly male performers, reinforcing the links between percussion and masculinity in many musical cultures, despite Lopes’s own work with women-dominant percussion groups. This pattern was disrupted in the final BatuConversa, a lecture-demonstration concert by the all-women Brazilian immigrant samba collective Gira. The group has become a staple of Lisbon’s nightlight since it originated in a workshop held during the pandemic by the international network of Mulheres na roda de samba (Women in samba circles). Gira’s explosion in popularity has allowed the musicians to leave often precarious work situations and embrace music as a full-time activity, as they now perform weekly and tour around Europe.

By attracting a younger, more female, and more politicized following, Gira stands out among the city’s weekly samba events, which are generally male-dominated. The table around which they perform is usually draped with a large trans-inclusive rainbow flag, promoting their aim to transform the samba tradition to be open to marginalized genders and sexualities. As one of the members explained, ‘Nobody questions where the women are in samba. The stereotype is either you are dancing or you are applauding the men. No, we want to be in the roda and be applauded too; we want to be on the microphone talking about what is important to us.’Footnote 50 They aim to create a ‘safe space’ in samba for immigrants, women, queer people and others traditionally excluded. The band’s name ‘Gira’ points to its Brazilian immigrant context in Portugal, as the word means to ‘turn’ or to ‘circle’, referring to the roda formation in which they perform as well as the Afro-Brazilian origins of samba they valorize, while, in European Portuguese, Gira is also a feminine adjective meaning ‘pretty’. They generally begin their concerts with the song ‘Deixa a Gira Girá’ (which is heard as ‘Let the pretty one turn’ in European Portuguese) by Os Tincoãs, a Bahian popular music band that drew on Candomblé elements in the 1960s. The song names Afro-Brazilian deities as origins of the lyrical voice. Like other rodas de samba, Gira primarily plays well-known songs to which the audience surrounding the roda enthusiastically sing along, but Gira’s particular repertoire selection highlights female musicians and Afro-Brazilian rhythms that are at the origins of samba. As one journalist wrote, ‘The fight against gender discrimination, racism and xenophobia is a large part of the group’s identity and is present in every detail: from the choice of repertoire to the place where they perform.’Footnote 51

In NBTT, the group sat near the African centre, taking hold of the instruments linked to the ship, as well as their own, and invited the visitors to encircle them inside (Figure 11). After a rendition of ‘Deixa a Gira Girá’, they recounted an origin story of samba as one of circulation, from Angola to Bahia to Rio de Janeiro, and now through immigration to Lisbon. Providing a groove on the cavaquinho (small chordophone), they introduced each instrument as it entered to fill in the polyrhythmic texture. The musicians presented different forms of samba, from the improvisational partido alto to full song forms, pairing down the instruments to show how they ‘conversed’ through interlocking rhythms. The group’s leader recounted how the cavaquinho was born in Braga, Portugal, and was bought to Brazil during colonization. She explained how their percussion instrumentation, including Afro-Brazilian percussion based in Candomblé to valorize this cultural heritage, which in other groups is rare or treated as an accessory, differentiates them from other rodas de samba. They use, for example, the atabaque drums of Candomblé and the unusual ilu, which was developed by enslaved Africans who, with no access to traditional percussion instruments, transformed barrels into drums. The ilu traditionally has a cross at its base, an element of syncretism that allowed the enslaved to maintain their musical and spiritual traditions while appearing to be practising Catholicism. Afro-Brazilian syncretic traditions were indeed often designed to be tolerated by the Portuguese colonizers while maintaining Afro-descendent traditions, such as capoeira, which disguised martial arts as dance. Finally, emphasizing the participatory element of NBTT, they broke the audience into groups and invited them to choose an instrument from the ship, assigning each group a rhythmic part that was combined to create the polyrhythm of ijexá. Over this chaotic texture, they sang ‘Emoriô’, resonating with the song’s selection at the opening event.

Figure 11. Gira’s BatuConversa.

In Gira’s NBTT performance, the ship became a space for the sharing of stories often excluded from elite institutions, and one media report even claimed that samba ‘invaded’ the MAAT at the BatuConversa, highlighting the genre’s alterity, even if without negative intent.Footnote 52 The group members recounted how the group’s professionalization had allowed a member who had worked for five years in domestic services to live from music performance. They asked the audience to imagine that a women’s roda might ‘become normal’, providing a performative inspiration for the normalization of women’s musical participation beyond their traditionally consigned roles. By placing their feminist posture in the decolonial context of NBTT, they advanced an intersectional critique of coloniality akin to what Maria Lugones calls that of ‘the coloniality of gender’, in her argument that the construction of normative gender and sexuality in Latin America was forged in the colonial encounter.Footnote 53 In other words, rather than solely seeking to decolonize the relationship between the ex-colony of Brazil and ex-metropole of Portugal through their performance, the Brazilian immigrant feminist collective extended Neto’s decolonial critique to a more encompassing assault on the intersecting social oppressions wrought by colonialism. In this way, the BatuConversas provided a space for the accumulation of meanings to the ship as the exhibition went on.

Closing

Entitled ‘The Ship Sets Sail’ (O barco vai de saida), the closing event inverted the structure that had been established in the opening. It began similarly with a concert of four percussion groups but ended in a parade that left the MAAT and processed west along the River Tagus. The opening thus had acted to install the work in the museum and the closing signalled its end, at once embodying the ship’s departure from the MAAT and referencing the departures of so many ships before. The work’s curator, Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, proclaimed in the programme notes of the event that the performance would manifest

a symbiotic ‘living body’ of sounds, rhythms, beats, and geographies … Symbolically, the encounters of sounds, rhythms, and beats from different parts of the world … can be seen as a counterpoint to the multitude of languages spoken across the world, alluding to the possibility, in specific moments and contexts, of languages that allow for communication beyond the verbal, enabling authentic and profound encounters.Footnote 54

While musically commenting on the opening event in particular, this final event also embodied the transformations the ship had experienced over the months of events which had been fundamentally out of Neto’s hands, highlighting the collaborative result of its time in Lisbon. For example, the intersectional curatorial approach of the final BatuConversa of highlighting female agency in music and percussion was expanded in the final event. It brought together previously participating groups, such as Bué Tolo and Bang Bang, with two new all women’s groups: Baque Mulher, a Brazilian ensemble playing maracatu of northeastern Brazil, and Adufe e Algiudar, a Portuguese women’s group dedicated to folkloric song accompanied by the Portuguese adufe (frame drum). In line with Neto’s vision of musical mixing, Adufe e Algiudar presents itself in the programme notes as a neo-folkloric group dedicated to diverse Portuguese traditions but open to experimentation, arrangement, and mixture: ‘The adufe is our mechanism of travel, like a square wheel that, with the help of sonic companions, takes us wherever we want to go. The alguidar – a bowl usually used for washing and kneading – is a metaphor for the reactiviation, reinvention and mixing of sounds.’Footnote 55