1. Introduction

Mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heteroliths are common in sedimentary successions throughout geological time (Haines, Reference Haines1988; Saylor, Reference Saylor2003; Tucker, Reference Tucker2003; Dibenedetto & Grotzinger, Reference Dibenedetto and Grotzinger2005; Gomez & Astini, Reference Gomez and Astini2015; Labaj & Pratt, Reference Łabaj and Pratt2016; Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Veiga, Trentini and Spalletti2016; Ferronatto et al. Reference Ferronatto, dos Santos Scherer, Drago, Rodrigues, de Souza, dos Reis, Bállico, Kifumbi and Cazarin2021). They constitute an essential sedimentary archive for interpreting basin-scale depositional processes and reconstructing regional stratigraphic frameworks across diverse tectonic and paleoenvironmental settings (Saylor, Reference Saylor2003; Tucker, Reference Tucker2003; McNeill et al. Reference McNeill, Cunningham, Guertin and Anselmetti2004; Longhitano et al. Reference Longhitano, Chiarella, Di Stefano, Messina, Sabato and Tropeano2012; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Muto2012a, b, Zeller et al. Reference Zeller, Verwer, Eberli, Massaferro, Schwarz and Spalletti2015; Rossi et al. Reference Rossi, Longhitano, Mellere, Dalrymple, Steel, Chiarella and Olariu2017; Ferronatto et al. Reference Ferronatto, dos Santos Scherer, Drago, Rodrigues, de Souza, dos Reis, Bállico, Kifumbi and Cazarin2021; Smrzka et al. Reference Smrzka, Kuzel, Chiarella, Joachimski, Vandyk, Kettler and Le Heron2022). However, these deposits have received considerably less attention than carbonate or siliciclastic-dominated deposits (Beukes, Reference Beukes1987; Lee & Kim, Reference Lee and Kim1992; Val et al. Reference Val, Aurell, Badenas, Castanera and Subias2019).

A defining feature of these mixed siliciclastic–carbonate deposits is hybrid sedimentation – the co-occurrence of siliciclastic and carbonate sediments in varying proportions and scales within the same depositional regime (Zuffa, Reference Zuffa1980; Schwarz et al. Reference Schwarz, Veiga, Álvarez Trentini, Isla and Spalletti2018). This hybrid system consists of both extrabasinal components (terrigenous siliciclastic grains) and intrabasinal components (autochthonous or parautochthonous carbonates), resulting in pronounced compositional and stratigraphic heterogeneity (Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). Hybridization results from the interaction of distinct depositional processes operating concurrently in the same basin – for instance: fluvial discharge delivering siliciclastic input into a shallow-marine setting with active carbonate production (Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). This interaction gives rise to a variety of mixed deposits at different scales, including alternations of lamina or lamina sets, and strata-scale interbedding of siliciclastic and carbonate facies (Mount, Reference Mount1984; Borer & Harris, Reference Borer and Harris1991a, b; Chiarella & Longhitano, Reference Chiarella and Longhitano2012; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano, Sabato and Tropeano2012b; Longhitano et al. Reference Longhitano, Chiarella, Di Stefano, Messina, Sabato and Tropeano2012), which may occur depending on different depositional processes, sediment supply, relative sea-level changes and/or climatic variations (Gillespie & Nelson, Reference Gillespie, Nelson, James and Clarke1987; Myrow & Landing, Reference Myrow and Landing1992; Sanders & Höfling, Reference Sanders and Höfling2000; Tucker, Reference Tucker2003; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017).

Thus, hybrid sedimentation (between siliciclastic and carbonate end-members) represents a transitional zone and provides particularly sensitive archives of paleoenvironmental changes. A thorough study of the depositional processes governing these mixed systems is therefore essential, as it not only elucidates the complex interactions between siliciclastic and carbonate sedimentation but also provides a robust framework for comprehensive reconstruction of basin evolution (Chiarella & Longhitano, Reference Chiarella and Longhitano2012; Cosovic et al. Reference Cosovic, Mrinjek, Nemec, Spanicek and Terzic2018; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2019; Smrzka et al. Reference Smrzka, Kuzel, Chiarella, Joachimski, Vandyk, Kettler and Le Heron2022).

Most research on mixed systems has focused on Phanerozoic successions (Dorsey & Kidwell, Reference Dorsey and Kidwell1999; McNeill et al. Reference McNeill, Cunningham, Guertin and Anselmetti2004; Breda & Preto, Reference Breda and Preto2011; Bourget et al. Reference Bourget, Ainsworth and Nanson2013; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). In contrast, Precambrian mixed siliciclastic–carbonate systems remain relatively underexplored, despite significant occurrences documented from the Mesoproterozoic (Turner, Reference Turner2009; Bellefroid et al. Reference Bellefroid, Planavsky, Hood, Halverson and Spokas2019), Tonian (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Rainbird and Dix2014), Cryogenian (Giddings et al. Reference Giddings, Wallace and Woon2009) and Ediacaran (Haines, Reference Haines1988).

In India, transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate sediments have been reported from a few Proterozoic basins (Mukhopadhyay & Chaudhuri, Reference Mukhopadhyay and Chaudhuri2003; Mukherjee & Bhattacharya, Reference Mukherjee and Bhattacharya2021; Chakraborty et al. Reference Chakraborty, Barkat and Sharma2023). However, the response of non-skeletal carbonate factories (sensu Smrzka et al. Reference Smrzka, Kuzel, Chiarella, Joachimski, Vandyk, Kettler and Le Heron2022) to siliciclastic influx in such mixed systems remains poorly constrained, and the processes governing these transitions are not yet well understood. In this study, we document an approximately 10 m-thick Mesoproterozoic heterolithic siliciclastic–carbonate deposit, laterally traceable for several tens of kilometres, that occurs at the transition between the Banaganapalle Formation and the Narji Limestone of the Kurnool sub-basin in India.

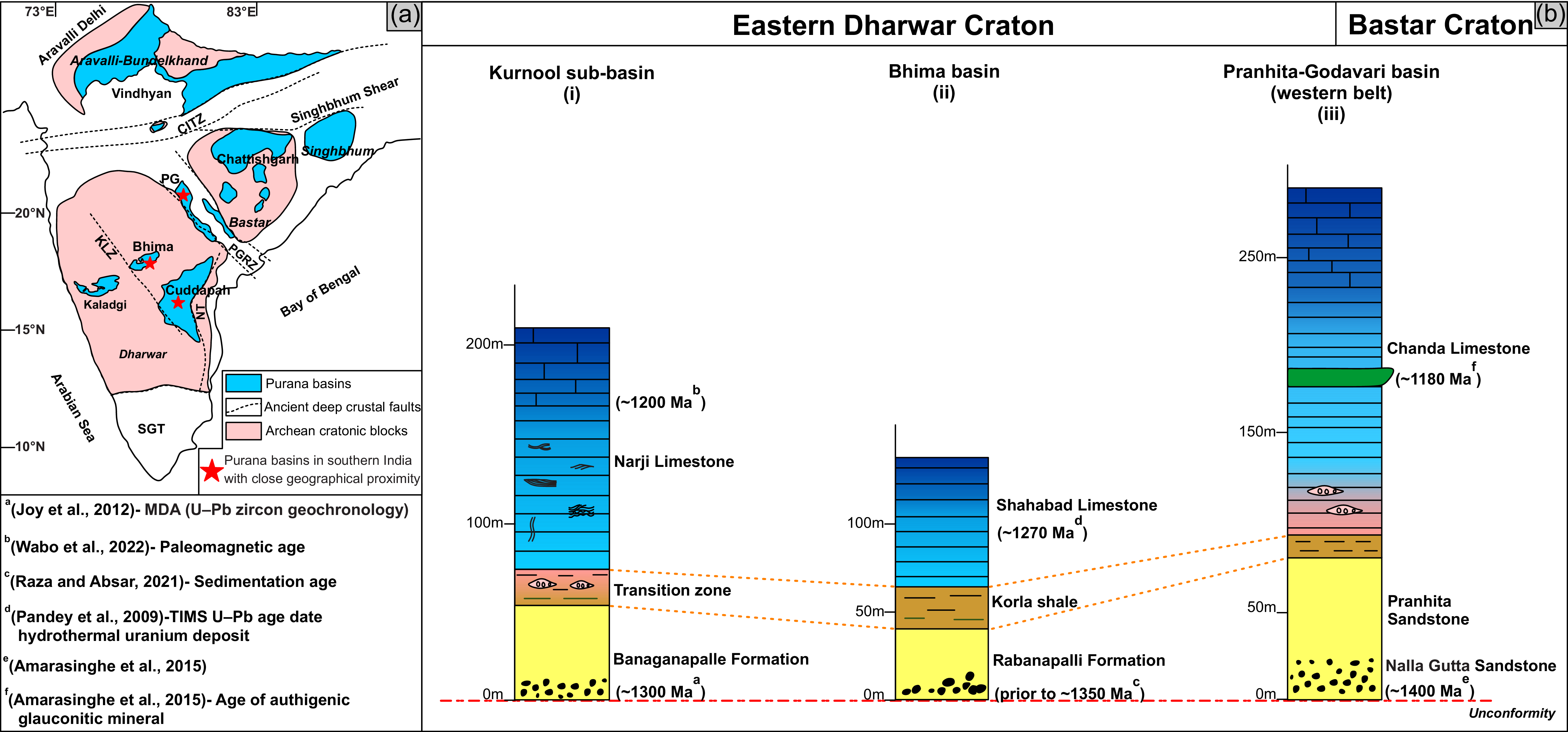

We present a detailed case study of macro and microscale mixing processes of these mixed deposits from the intracratonic Kurnool sub-basin (Figure 1c). This analysis highlights the potential of these mixed deposits to record variations in paleoenvironmental conditions and provides insights into the depositional dynamics of the Proterozoic mixed systems.

Figure 1. (a) Generalized geological map of India showing the location of the Cuddapah Basin. (b) Simplified geological map of the Proterozoic Cuddapah Basin showing the sub-basins and boundary thrusts. Study area in the Kurnool sub-basin is marked by a red rectangle. GKF – Gani-Kalva Fault; KF – Kona Fault; AF – Atmakur Fault (after Saha & Tripathy, 2012). (c) Geological map of the Kurnool sub-basin with locations of studied sections marked by black boxes (i and ii) (modified after GSI Bhukosh portal): i) Sugalimetta section and ii) Ujjalawada section.

The present study aims to: i) reconstruct the depositional environment of the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate succession, ii) develop a depositional model explaining the tectono-sedimentary evolution from a siliciclastic system, through a mixed heterolithic deposit, to a carbonate platform, iii) characterize the scale of mixing between the siliciclastic and carbonate components, in terms of sedimentary processes, and iv) assess potential lithostratigraphic correlation with similar mixed siliciclastic–carbonate deposits from other Proterozoic intracratonic basins of southern Peninsular India.

2. Geological setting

2.a. Regional geology

Proterozoic intracratonic basins of Peninsular India, collectively known as the Purana basins (Holland, Reference Holland1909), are characterized by flat-lying to gently dipping strata (≤ 5°), except near intrabasinal and basin-margin faults (Hoffman, Reference Hoffman1989; Goodwin, Reference Goodwin1996). The Cuddapah Basin (Figure 1a, b), the second-largest Purana basin in India, contains ∼7.9 km of sedimentary fill (Kale et al. Reference Kale, Saha, Patranabis-Deb, Sesha Sai, Tripathy and Patil-Pillai2020), recording multiple sandstone–carbonate–shale cycles from the late Paleoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic (Ramakrishnan & Vaidyanadhan, Reference Ramakrishnan and Vaidyanadhan2010; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012; Saha & Tripathy, Reference Saha and Tripathy2012a, Reference Saha and Tripathy2012b; Tripathy et al. Reference Tripathy, Satyapal Mitra, Sesha Sai and Mukherjee2019). The youngest Kurnool Group, approximately 500 m thick (Nagaraja Rao et al. Reference Nagaraja Rao, Rajurkar, Ramalingaswamy, Ravindra Babu and Radhakrishna1987), is separated from the underlying Cuddapah Supergroup by an angular unconformity in the western part of the Cuddapah Basin (Saha & Tripathy, Reference Saha and Tripathy2012a) (Figure 1b). In the Erraguntla area (Kurnool sub-basin), the basal Kurnool Group is separated from the underlying Tadpatri Formation of the Chitravati Group by an angular unconformity (Chaudhuri et al. Reference Chaudhuri, Saha, Deb, Deb, Mukherjee and Ghosh2002; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012), whereas further west in the Palnad sub-basin, it rests unconformably on the Peninsular Gneiss (Saha et al. Reference Saha, Ghosh, Chakraborty and Chakraborti2009, Reference Saha, Patranabis-Deb, Collins, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2016).

The Kurnool Group (Figure 1c) comprises unmetamorphosed and undeformed sedimentary rocks, forming two cycles of sandstone–limestone–shale litho-packages that are subdivided into six formations (Saha et al. Reference Saha, Ghosh, Chakraborty and Chakraborti2009; Ramakrishnan & Vaidyanadhan, Reference Ramakrishnan and Vaidyanadhan2010; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012). The basal Banaganapalle Formation (50 m) consists of diamond-bearing conglomerates and coarse–to fine-grained sandstones (Chaudhuri et al. Reference Chaudhuri, Saha, Deb, Deb, Mukherjee and Ghosh2002; Saha et al. Reference Saha, Ghosh, Chakraborty and Chakraborti2009; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012). The Banaganapalle Formation passes through a siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit (10 m) that is capped by the Narji Limestone (140 m). The siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit is composed of laterally extensive intraformational conglomerate, calcareous shale–carbonate, and thin glauconitic sandstone. The tuffaceous Owk Shale (approximately 15–20 m) overlies the Narji Limestone, followed by the Panium Quartzite (35–50 m thick), the Koilkuntala Limestone (5–10 m thick), and the calcareous Nandyal Shale (50–100 m thick) in stratigraphically ascending order (Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012).

2.b. Age of deposition

The depositional age of the Kurnool sub-basin remains uncertain (Saha et al. Reference Saha, Patranabis-Deb and Banerjee2024). However, detrital zircons recovered from heavy mineral stream samples around diamond-bearing lamprophyre exhibit a younger age range between 1284 and 1370 Ma and are interpretated as the emplacement age of the lamproite dykes (Joy et al. Reference Joy, Jelsma, Preston and Kota2012). These dykes appear to be the source of diamonds found in the basal conglomerates of the Banaganapalle Formation (Joy et al. Reference Joy, Jelsma, Preston and Kota2012), indicating that the sedimentation in the Kurnool sub-basin began after ⁓1.3 Ga. Alternatively, the emplacement of kimberlites in the Eastern Dharwar Craton (EDC) around 1.1 Ga (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Heaman and Manikyamba2007; Babu et al. Reference Babu, Griffin, Mukherjee, O’Reilly, Belousova, Foley, Aulbach, Brey, Grütter, Höfer, Jacob, Lorenz, Stachel and Woodland2008; Chalapathi Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wu, Mitchell, Li and Lehmann2013) might also have served as the diamond provenance of the Banaganapalle Formation. Therefore, the emplacement age of the lamproite and kimberlite dykes provides constraints on the initiation of the Kurnool sub-basin sedimentation, indicating that sedimentation in the sub-basin occurred after ∼1.3 to 1.1 Ga. Ar-Ar step-heating analysis of glauconitic sandstone from the Narji Limestone capping the Banaganapalle Formation yielded ages between 750 Ma and 1000 Ma (Wabo et al. Reference Wabo, Beukes, Patranabis-Deb, Saha, Belyanin and Kramers2022). On the other hand, paleomagnetic data from the Narji Limestone suggest a Mesoproterozoic (∼1.2 Ga) age of deposition (Wabo et al. Reference Wabo, Beukes, Patranabis-Deb, Saha, Belyanin and Kramers2022; De Kock et al. Reference De Kock, Malatji, Wabo, Mukhopadhyay, Banerjee and Maré2024). Limestone xenoliths have also been reported from the 1093 ± 18 Ma Siddanpalli dyke located between the Bhima basin and Kurnool sub-basin (Dongre et al. Reference Dongre, Chalapathi Rao and Kamde2008; Chalapathi Rao et al. Reference Chalapathi Rao, Anand, Dongre and Osborne2010; Chalapathi Rao et al. Reference Rao, Wu, Mitchell, Li and Lehmann2013). If the limestone xenoliths are from these basins, then the Narji Limestone was deposited >1.1 Ga (Basu & Bickford, Reference Basu and Bickford2015).

The detrital zircon population from the Kurnool sub-basin, particularly from the Owk Shale and the Banaganapalle Quartzite, suggested the depositional age older than 2522 ± 36 Ma for these formations. However, the presence of a single zircon grain dated at 1880 ± 8 Ma and three zircon grains ca. 1300 Ma suggests that sedimentation in the Kurnool sub-basin commenced after 1.3 Ga (Babu, Reference Babu2011; Joy et al. Reference Joy, Jelsma, Preston and Kota2012; Bickford et al. Reference Bickford, Saha, Schieber, Kamenov, Russell and Basu2013). Detrital zircon analyses from the overlying Panium Quartzite yield a maximum depositional age of approximately 913 Ma (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Patranabis-Deb, Alexander, Bertram, Falster, Gore, Mackintosh, Dhang, Saha, Payne and Jourdan2015). Most of the dated detrital zircon grains belong to older Paleoproterozoic age (2061 ± 22 Ma) populations, with the exception of a single near-concordant Neoproterozoic zircon dated at 913 ± 11 Ma. This Neoproterozoic age is significantly younger than the next youngest concordant age (1717 ± 20 Ma, based on five detrital zircon grains). This isolated occurrence of 913 Ma age may be attributed to analytical uncertainty or due to contamination (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Patranabis-Deb, Alexander, Bertram, Falster, Gore, Mackintosh, Dhang, Saha, Payne and Jourdan2015). Nevertheless, the 913 Ma age is considered to constrain the maximum depositional age of the Panium Quartzite (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Patranabis-Deb, Alexander, Bertram, Falster, Gore, Mackintosh, Dhang, Saha, Payne and Jourdan2015, Saha et al. Reference Saha, Patranabis-Deb and Banerjee2024). The dominant cluster of Palaeoproterozoic detrital zircon ages (2061 ± 22 Ma) likely reflects the principal provenance signature, implying that the bulk of Kurnool sedimentation postdates the main age cluster of the Palaeoproterozoic-aged detrital zircons.

Biostratigraphic data based on organic-walled microfossils indicate a late Neoproterozoic age for the Owk Shale (Shukla et al. Reference Shukla, Sharma and Sergeev2020). If the Kurnool sub-basin were indeed of the late Neoproterozoic age, it would be reasonable to expect the presence of detrital zircons younger than 1000 Ma, derived from the uplifted Eastern Ghats following the India–East Antarctica collisional event at approximately 1000 Ma (Basu & Bickford, Reference Basu and Bickford2015). The interpretation of detrital zircon provenance of the Kurnool Group is complex, as it depends not only on available source areas but also on the direction of sediment transport. Given the reported northeasterly to southeasterly paleocurrent directions from the Banaganapalle Formation (Lakshminarayana et al. Reference Lakshminarayana, Bhattacharjee and Kumar1999), it is plausible that the Kurnool sub-basin primarily received detritus from the older Dharwar Craton and/or the older Cuddapah sedimentary succession rather than from the highlands of the Eastern Ghats. Therefore, the absence of <1000 Ma zircons questions the proposed late Neoproterozoic biostratigraphic age assignment for the Kurnool sub-basin (Basu & Bickford, Reference Basu and Bickford2015). However, it should also be noted that if the sediments of the Kurnool Group were not sourced from the uplifted Eastern Ghats, then the detrital zircon ages cannot conclusively rule out a Neoproterozoic biostratigraphic age of deposition.

Radiometric and paleomagnetic age data is favoured here over the paleontological evidence, supporting a Mesoproterozoic depositional age (in between approximately 1.3 to 1.1 Ga) of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin (cf. Basu & Bickford, Reference Basu and Bickford2015).

3. Methodology

Geological traverses were carried out along road-cut sections and hill sections across the Nandyal district, the Kurnool sub-basin, India. Geological mapping was carried out at a 1:50000 scale on topographic maps and open series maps of the Geological Survey of India (GSI Bhukosh), supplemented with Google Earth imagery, SRTM data and previously published maps (Saha & Tripathy, Reference Saha and Tripathy2012; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012). To investigate lateral and temporal variations in the lithostratigraphic units of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin, two key sections were measured at a road cut along NH-40 (connecting Nandyal-Kurnool (15.54752°N, 78.2951°E); Figure 1c–(i)) (approximately 8 m thick) and another at Ujjalawada (15.62235°N, 78.06493°E) (approximately 8–10 m thick); Figure 1c–(ii)). Additional traverses along road cuts and hill sections were conducted to further examine the stratigraphic and sedimentological characteristics of the succession. Lithofacies were identified, and a composite litholog (Figure 2a) was constructed based on grain size, colour, primary sedimentary structure, thickness and sandstone–shale–carbonate relative proportions. Paleocurrent data were also collected from the Banaganapalle Formation. Petrographic analysis of ten thin sections prepared from the transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit was carried out using a Leica DMP4 microscope. For the identification of carbonate mineral phases, Alizarin Red S staining was performed on some thin sections following the standard procedure.

Figure 2. (a) Lithostratigraphic log of the sedimentary succession of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin. (b) Representative composite litholog of the transitional unit between the Banaganapalle Formation and the Narji Limestone.

4. Results

4.a. Banaganapalle Formation

The Banaganapalle Formation, with a maximum thickness of 50 m (Figure 2a), consists of indurated fine-to coarse-grained brown-to yellow-white-coloured, well-to moderately sorted sandstones with a subordinate proportion of clast-to matrix-supported polymictic conglomerates. The basal section of the Banaganapalle Formation is composed of clast-supported to locally matrix-supported, crudely horizontally stratified (Figure 3a) conglomerate beds (individual bed thickness varies between 0.3 to 1 m). Framework clasts (ranging between 2 to 15 cm) are subangular to subrounded, poorly to moderately sorted, and composed of mudstone, shale, jasper, sandstone, quartzite, dolerite, vein quartz, silicified stromatolitic limestone, oolitic chert and black chert. The basal conglomerate beds transition upwards into interbedded conglomerate–cross-stratified pebbly sandstones (5–15 cm set thickness, 40–60 cm bed thickness, Figure 3b). This unit is followed by largely massive, polymictic conglomerates with normal to reverse grading, crude horizontal stratification in places, and sharp basal contacts. In some areas, these conglomerate beds exhibit lenticular, concave-upward, undulating erosive bases (from few tens of cm to 1 m depth).

Figure 3. Field photographs of the coarse-to fine-grained Banaganapalle sandstone. (a) Clast-supported polymictic conglomerate with subangular to subrounded clasts. (b) Interbedding of conglomerate and cross-stratified pebbly sandstone unit. (c) Heterolithic unit of sandstone and silty mudstone with pinch-and-swell geometry. (d) Combined-flow-generated low-angle cross-stratified medium-to fine-grained sheet-like sandstone bed. (e) Trough cross-stratified medium-grained sandstone unit. (f) Well-developed herringbone cross-stratification and tidal bundles within medium-to fine-grained sandstone. (g) Adhesion ripple-laminated sandstone unit. (h) Pin-stripe parallel laminae alternating with well-developed, wedge-shaped cross-strata with alternating coarse-and fine-grained foreset layers. Field photographs of the Narji Limestone: (i) Syn-sedimentary deformation structures and sand dykes cutting through the whitish-grey limestone beds. (j) Well-preserved sand lenses in the grey limestone. (k) Discordant breccia bodies formed by angular to subangular intraformational carbonate clasts within whitish-grey limestone. (l) Grey flaggy limestone with wavy to low-angle cross-laminations. (m) Several bed-parallel mature stylolites within the greyish-black limestone beds. (n) Plane-parallel-laminated, black limestone.

The conglomerate deposits are capped by medium-to fine-grained, planar cross-stratified sandstone beds (15–35 cm thick) exhibiting southeast-directed paleoflow. Stratigraphically up, these medium-to fine-grained cross-stratified sandstone beds alternate with wavy-laminated silty mudstone layers (2–10 cm thick), forming an approximately 1.8 m-thick heterolithic unit with pinch-and-swell geometries (Figure 3c).

The heterolithic unit transitions upward into medium-grained sandstone beds (15–90 cm thick) interbedded with 10–50 cm-thick pebbly sandstone sheets. These sandstones exhibit wavy laminations, low-angle cross-stratification (4–10 cm set thickness, Figure 3d), hummocky and swaley cross-stratification, planar tabular cross-stratifications (5–20 cm set thickness), and occasionally trough cross-stratifications (4–12 cm thick, Figure 3e) with an easterly paleo-flow.

Higher in the succession, the medium-grained sheet-like sandstone beds are dominated by combined-flow-generated structures alternating with 1–1.5 m-thick, sheet-like heterolithic deposits. These heterolithic deposits consist of wavy-laminated silty mudrock and wave ripple-laminated fine-grained sandstone. This heterolithic unit is overlain by medium-grained, dominantly trough cross-stratified (3–7 cm set thickness), sheet-like sandstone beds.

Stratigraphically above this, a 3–4 m-thick alternation of fine-to medium-grained sandstone and silty mudstone exhibits planar and trough cross-stratification (4.5–20 cm and 3–14 cm, respectively), herringbone cross-stratification (5–30 cm per set, Figure 3f), tidal bundles (Figure 3f), wavy laminations, lenticular and flaser bedding, adhesion ripple lamination and interference ripples, with a bidirectional paleocurrent pattern predominantly towards the SSW.

The uppermost part of the Banaganapalle Formation is composed of a 7-m-thick sheet-like, very fine-to fine-grained sandstone deposit. Its lower portion features adhesion ripple lamination (4–8 cm set thickness, Figure 3g), wind-ripple strata (4–15 cm set thickness, Figure 3h) and 2–8 cm-thick wedge-shaped cross-stratifications (Figure 3h), with a polymodal paleocurrent dominated by east-and southwest-directed flow. The upper portion is composed of fine-to medium-grained, trough cross-stratified (10–30 cm thick) and swaley cross-stratified (wavelengths of 80 cm to 3.5 m, maximum amplitude ∼15 cm) sandstone beds (30–60 cm thick) interbedded with wavy-laminated silty mudrock layers. The cross-stratified sandstone shows NE-directed paleoflow direction (Figure 2a). A clast-supported cobbly to pebbly conglomerate layer (10–20 cm thick), laterally extensive over tens of kilometres, sharply overlies the sandstone beds, marking the end of siliciclastic deposition of the Banaganapalle Formation.

4.a.1. Depositional environment

The basal crudely horizontal stratified clast-supported conglomerates and interbedded pebbly to coarse-grained cross-stratified sandstones indicate subaerial hyperconcentrated flow deposits (Sohn et al. Reference Sohn, Rhee and Kim1999; Saula et al. Reference Saula, Mato, Puigdefabregas, Martini, Baker and Garzón2002). Overlying massive to crude horizontally stratified, matrix-to clast-supported conglomerate unit indicates subaqueous cohesive debris flow deposits (Blair & McPherson, Reference Blair and McPherson1998), with local scouring surfaces suggesting deposition from coarse-grained hyperconcentrated turbulent flows (Nemec & Steel, Reference Nemec, Steel, Koster and Steel1984; Mulder & Alexander, Reference Mulder and Alexander2001; Benvenuti & Martini, Reference Benvenuti, Martini, Martini, Baker and Garzón2002; Benvenuti, Reference Benvenuti2003). The conglomeratic basal section of the Banaganapalle Formation is attributed to alluvial fan to fan-delta environments at tectonically active basin margins (Collinson, Reference Collinson and Reading1996).

Planar cross-stratified sandstone interbedded, alternating with heterolithic fine-grained cross-stratified sandstone and wavy-laminated silty mudstone with a pinch-and-swell geometry, represents mouth bar deposits associated with shallow-delta distributary channels, forming a distributary channel–mouth bar complex (Gloppen & Steel, Reference Gloppen and Steel1981; Shultz, Reference Shultz1984; Nemec & Steel, Reference Nemec, Steel, Koster and Steel1984).

Fan delta deposits grade into sheet-like sandstone bodies, characterized by low-angle cross-stratification, wavy lamination, hummocky-to-swaley cross-stratification, and occasional planar tabular cross-strata and trough cross-strata, indicating a shoreface-to-foreshore environment (Cheel & Leckie, Reference Cheel and Leckie1992; Dumas et al. Reference Dumas, Arnott and Southard2005; Dumas & Arnott, Reference Dumas and Arnott2006; Perillo et al. Reference Perillo, Best and Garcia2014).

Ripple-laminated sandstone with thin silty mud partings, interference wave ripples, desiccation cracks, wavy-lenticular-flaser bedding, and oppositely oriented planar cross-bedding suggest a tidal flat environment with periodic subaerial exposure in a foreshore setting (Reineck & Wunderlich, Reference Reineck and Wunderlich1968; Fan et al. Reference Fan, Li, Wang, Wang, Archer and Greb2004; Kale et al. Reference Kale, Pundalik, Karmalkar, Duraiswami and Mukherjee2021).

The tidal flat gradually grades into sandstone sheets, that are characterized by the presence of abundant adhesion structures indicating subaerial exposure and aeolian activity (Kocurek & Fielder, Reference Kocurek and Fielder1982). Planar cross-sets with well-developed wedge-shaped foresets are interpreted as probable remnants of aeolian dunes (Hunter, Reference Hunter1977). The polymodal palaeocurrent pattern, adhesion structures, and wind-ripple strata gradationally overlying the tidal flat suggest deposition in a sandy foreshore–backshore setting in a shallow clastic linear coastal plain (Chakraborty & Sensarma, Reference Chakraborty and Sensarma2008). Interlayered aqueous and adhesion strata probably indicate repeated marine inundation and continuous aeolian reworking of dry sands, forming sand sheet deposits (Kocurek & Fielder, Reference Kocurek and Fielder1982; Dalrymple et al. Reference Dalrymple, Narbonne and Smith1985; Chakraborty & Sensarma, Reference Chakraborty and Sensarma2008).

Above the sand sheet deposits, heterolithic sandstone–silty mudstone with swaley cross-stratification, trough cross-stratification, wave ripples and a polymodal to bipolar paleocurrent pattern signify a relative sea-level rise and deposition in a shallow-marine upper shoreface setting of the Precambrian clastic deposits (Anderton, Reference Anderton1976; Soegaard & Eriksson, Reference Soegaard and Eriksson1985; Chakraborty & Sensarma, Reference Chakraborty and Sensarma2008). The sharp occurrence of a transgressive lag surface above this upper shoreface deposit marks a sudden rise in relative sea level.

4.b. Mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit

The mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit (Figure 2b) sandwiched between the siliciclastic Banaganapalle Formation and the Narji Limestone can be classified into three lithofacies associations: 1) Clayey siltstone with very fine-grained thick tabular glauconitic sandstone, 2) Mixed calcareous shale–carbonate–siliciclastic heterolith, and 3) Intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate intercalated with calcareous shale and tabular-bedded limestone (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of the facies associations in the transition zone mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit and their depositional environments

4.b.1. Facies association 1 (FA1): Clayey siltstone with very fine-grained, thick, tabular glauconitic sandstone

This facies association is approximately 3.5 m thick and laterally persistent for over hundreds of metres. The lower 2.5 m of this facies association predominantly consists of yellow-coloured, parallel-laminated clayey siltstone having millimeter-scale lamina to lamina sets (Figures 4a and 4b) interbedded with distinct tabular sheets of very fine-to fine-grained, green-coloured glauconitic sandstone (1–15 cm in thickness) (Figure 4c). Notably, the glauconitic sandstone beds display combined-flow ripple lamination (1–2 cm thick) and wavy lamination. These glauconitic sandstone beds are bounded by wavy tops and sharp flat bases within the clayey siltstone layers. The bed thickness of glauconitic sandstone decreases upwards, where the glauconitic layer mostly appears as thin streaks. This clayey siltstone unit gradually transitions into a mixed calcareous shale–carbonate–siliciclastic heterolithic unit, suggesting an increase in the calcareous component stratigraphically upwards (Figure 2b).

Figure 4. (a) Litholog of the lower part of the transition zone. (b) Parallel-laminated clayey siltstone beds interbedded with distinct tabular sheets of green glauconitic sandstone beds (highlighted by the red box). (c) Arrow from photograph (b) indicating a thick, medium-to fine-grained glauconitic sandstone bed. (d) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of yellow, very fine-grained, parallel-laminated clayey siltstone (scale bar – 750 µm). (e) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of calcite cement present in the interstitial spaces of fine-grained quartz grains (Qtz) (scale bar – 250 µm). (f) Photomicrograph under plane-polarized light of siltstone containing glauconite grains (marked by red arrows) (scale bar – 500 µm). (g) Photomicrograph under plane-polarized light of medium-to fine-grained, well-sorted, quartz-rich glauconitic sandstone. Glauconite grains (yellowish) (Gl) occur as subrounded peloids with highly irregular boundaries. Stratigraphic positions of photomicrographs d to g are marked in b (scale bar 750 µm).

Petrography of FA1: Petrographic analysis reveals that the parallel-laminated clayey siltstone (Figure 4d) contains patches of fine detrital quartz grains along with carbonate cementation (calcite with little dolomite) in the interstitial pore spaces (Figure 4e). Notably, the concentration of carbonate cement (calcite with little dolomite) within the pore spaces increases upwards (Figure 4b). The parallel-laminated clayey siltstone gradually transitions into very fine siltstone, with an increase in the proportion of glauconite grains (Figure 4f) and eventually into very fine-to fine-grained glauconitic sandstones (Figure 4g). These sandstones are well-sorted, subangular, quartz-rich, and contain 5 to 10% detrital feldspar with a small proportion of carbonate cement (calcite with little dolomite). Some quartz grains exhibit overgrowths, and the matrix content never exceeds 10%. Glauconitic minerals are found as subrounded peloids with highly irregular boundaries. The long axis of these glauconitic peloids ranges from 50 to 250 µm. In plane-polarized light, glauconitic peloids are pleochroic in nature and vary from yellowish-green to dark green in colour (Figure 4g). Under cross-polarized light, the glauconitic minerals display either aggregate or pinpoint extinctions and appear cryptocrystalline to microcrystalline in form. These glauconite grains make up approximately 25% of the rock by volume within the parallel-to-wavy-laminated clayey siltstone facies.

4.b.1.a. Depositional environment

Parallel-laminated clayey siltstone beds indicate low-energy offshore deposition below the storm wave base, where sediments slowly settled in partially restricted environments (Odin & Matter, Reference Odin and Matter1981; Ireland et al. Reference Ireland, Curtis and Whiteman1983). Sharp-based combined-flow ripple-laminated glauconitic sandstone interbedded with parallel-to-wavy-laminated clayey siltstone reflects the dynamic interplay of low-energy background sedimentation and episodic storm events, indicating deposition in a storm-induced middle-to inner-shelf environment with a higher degree of clastic dilution (Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018, Bansal et al. Reference Bansal, Banerjee and Nagendra2020). Glauconite is commonly considered a product of authigenesis in a marine depositional realm (Odin & Matter, Reference Odin and Matter1981; Amorosi, Reference Amorosi1995, Reference Amorosi1997; Harris & Whiting, Reference Harris and Whiting2000; Giresse & Wiewióra, Reference Giresse and Wiewióra2001; Meunier & El Albani, Reference Meunier and El Albani2007; Chattoraj et al. Reference Chattoraj, Banerjee and Saraswati2009; Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Jeevankumar and Eriksson2008, Reference Banerjee, Chattoraj, Saraswati, Dasgupta and Sarkar2012a,b) and formed at or very close to the sediment–water interface (Gomez & Astini, Reference Gomez and Astini2015), at a transition zone between oxidizing conditions above and reducing conditions below (Ireland et al. Reference Ireland, Curtis and Whiteman1983; Conrad et al. Reference Conrad, Hein, Chaudhuri, Patranabis-Deb, Mukhopadhyay, Deb and Beukes2011). Though uncommon in the Proterozoic sedimentary successions, glauconite typically forms in restricted shelf environments (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Bansal and Thorat2016; Tang et al. Reference Tang, Shi, Ma, Jiang, Zhou and Shi2017; Bansal et al. Reference Bansal, Banerjee and Nagendra2020). The presence of glauconitic peloids, which are smaller in size than associated detrital grains and exhibit no spatial relationship with stratification, indicates their in situ early diagenetic glauconitization and ceased once pore spaces were eliminated by overgrowth formation (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Jeevankumar and Eriksson2008).

Petrographic evidence reveals increased carbonate (calcite with little dolomite) cementation stratigraphically upwards within grain interstices, reflecting enhanced carbonate saturation within pore waters, which may potentially be associated with a shallowing-upward depositional trend. Additionally, the presence of carbonate cementation with glauconitic grains suggests early cementation at the sediment–water interface (McBride, Reference McBride1988; Chafetz & Reid, Reference Chafetz and Reid2000). Besides, the absence of any displacement or breakage of carbonate (mostly calcite) cements in pore spaces of the glauconitic sandstones supports its syn-depositional formation within FA1 (Chafetz & Reid, Reference Chafetz and Reid2000).

4.b.2. Facies association 2 (FA2): mixed calcareous shale–siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith

FA1 gradually transitions into a 4 to 5 m-thick heterolithic unit (Figures 2b and 5a), predominantly composed of mauve to brown calcareous shale, glauconitic sandstone, and limestone with well-defined fissility planes. The lower 2 to 3 m of FA2 is characterized by wavy-to parallel-laminated (2–3 cm) very thin calcareous shale (Figure 5b), and laterally impersistent glauconitic sand lenses and stringers (a few mm to 1 cm) (Figure 5b) with sharp basal contacts and wavy top surfaces. Ripple cross-lamination (up to 1 cm) can be observed in these thin sand lenses, and wave ripples are locally observed on the bedding plane surfaces. Additionally, pale brown to buff-coloured mm-thin silt layers occur in variable proportions, mantled by calcareous shale (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. (a) Litholog of the heterolithic unit of the lower-middle part of the transition zone. (b) Field photograph of wavy-to parallel-laminated, very thin calcareous shale alternating with laterally impersistent glauconitic sand stringers, showing sharp basal contacts and wavy top contacts. (c) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of parallel-laminated calcareous shale (scale bar – 500 µm). (d) Photomicrograph under plane-polarized light showing calcareous shale interbedded with very fine-grained glauconite-quartz-rich layers. Detrital grains are angular to subangular. The upper contact of the glauconitic quartz-rich layers exhibits asymmetric convex-up top, occasionally preserves ripple top geometry (marked by red arrow), while the lower contact forms an undulating erosive bounding surface. The photomicrograph was taken using a high-resolution scanner. Red boxes (1, 2 and 3) indicate different textural characteristics in the heterolithic unit. (e) Photomicrograph under plane-polarized light of fine-grained, poorly sorted, subangular to angular glauconitic sandstone composed mainly of quartz, feldspar and glauconite grains (scale bar – 500 µm). (f) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of subangular to subrounded quartz and glauconite grains with calcite cement present in the interstitial pore spaces (scale bar – 250 µm). (g) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of locally developed normal to reverse grading within fine-grained glauconitic sand layers associated with calcareous shale, marked by the red box, named ‘1’ (scale bar – 750 µm). (h) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of a glauconitic sand layer forming a small scour within the calcareous shale, marked by the red box, named ‘2’ (scale bar – 750 µm). (i) Litholog of the heterolithic unit of the upper-middle part of the transition zone. (j) Field photograph of thin, mauve-coloured calcareous shale alternating with mauve-coloured, tabular-bedded limestone. (k) Field photograph of laterally impersistent, very thin, fine-grained sand lenses, embedded within calcareous shale mainly. (l) Field photograph of thin, discontinuous laminae of very fine-grained sandstone. (m) High-resolution scanned photomicrograph of alternating calcareous shale and micritic limestone layers, with detrital quartz and feldspar grains occurring as lenses or patches within the calcareous shale unit. (n) and (o) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of the calcite cement (Figure 5n) in the fine-grained discontinuous sand stringers, made mainly by quartz grains and a few subangular to subrounded calcite grains are also present as floated grains (Figure 5n and o) within the calcareous shale layers (scale bar for Figure 5n–250 µm and for Figure 5o–500 µm). (p) Photomicrograph under cross-polarized light of angular to subangular fine quartz along with calcite grains (scale bar – 500 µm).

The upper part of FA2 (1 to 2 m thick) (Figure 5i) consists of thin (1–3 cm) mauve-coloured calcareous shale, alternating with mauve-coloured tabular-bedded limestone (a few mm to 2 cm thick) (Figure 5j), and mm-thin very fine-grained sand lenses, streaks or stringers (Figure 5k). Very fine-grained sand lamina sets have sharp bases and pinch out laterally over a distance of 3–4 cm, lacking distinct sedimentary features (Figure 5l). The limestone beds (a few mm to 2 cm thick) within this heterolithic unit are either massive or exhibit diffuse millimetre-scale parallel to wavy laminations.

Petrography of FA2: Petrographic characteristics of the lower part of FA2 indicate the presence of wavy-to parallel-laminated, brown calcareous shale (Figure 5c), interspersed with a few fine-grained detrital quartz grains. This µm to several mm-thick calcareous shale unit is well segregated and alternates with mm-thick, fine-grained, poorly sorted, subangular to subrounded siliciclastic layers (Figure 5d), made up of quartz, feldspar, mica and glauconite grains (Figure 5e) with calcite cement (Figure 5f). The glauconitic siliciclastic layers locally develop normal to reverse grading (Figure 5g) and form undulating erosive lower bounding surfaces with occasional scouring (Figure 5h). The proportion of glauconitic sand lenses and stringers is greater in the lower part of this facies association (Figure 2b). Stratigraphically upwards, there is a gradual decrease in siliciclastic layers and an increase in calcite cementation.

Petrographic characteristics of the upper part of FA2 reveal calcareous shale alternating with thin and thick (mm to cm) layers of micritic limestone and a few discontinuous layers of very fine sand stringers. Photomicrographs show moderate segregation of different lithological units in this micro-facies association at the lamina scale (Figure 5m). Along with predominantly calcitic (Figure 5n) in the thin, fine-grained discontinuous sand stringers, a few sub-rounded to well-rounded calcite grains are also present as floated grains (Figures 5n, o) within the calcareous shale layers. The sand stringers are predominantly composed of angular to subangular quartz and calcite grains and devoid of glauconite grains (Figure 5p). Microscopic examination also reveals the alternating layers of calcareous shale, micritic limestone and fine-grained sandstone forming a mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith. The carbonate content increases stratigraphically upwards in FA2.

4.b.2.a. Depositional environment

In the basal part of this facies association, the ripple-laminated glauconitic sand lenses suggest formation by episodic storm-induced offshore-directed bottom currents or by shore-parallel to shore-oblique geostrophic currents (Aigner & Reineck, Reference Aigner and Reineck1982; Snedden et al. Reference Snedden, Nummedal and Amos1988; Leckie & Krystinik, Reference Leckie and Krystinik1989; Duke, Reference Duke1990; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018). The parallel-laminated calcareous shale unit within this mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith indicates deposition from suspension in a low-energy environment (Flügel & Munnecke, Reference Flügel and Munnecke2010; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018; Newport, Reference Newport2019). The well-segregated glauconite-quartz-rich siliciclastic layers, which formed alternatively with the carbonate-rich brown calcareous shale, exhibit normal to reverse grading and erosive undulating lower boundaries. These features suggest deposition influenced by storm events and/or gravity-driven processes in an outer-to middle-shelf environment (Wilson, Reference Wilson1967; McNeill et al. Reference McNeill, Cunningham, Guertin and Anselmetti2004; Halfar et al. Reference Halfar, Ingle and Godinez-Orta2004; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018). The action of storm surges likely eroded into the underlying calcareous shale unit (Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018).

The decrease in silt and glauconitic sand laminae frequency, along with an increase in carbonate content within the calcareous shale, suggests a shift from well-segregated to moderately segregated deposits in the upper stratigraphic levels of the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit. Microscopically, the presence of alternating layers of micritic limestone and moderately segregated calcareous shale with discrete quartz, calcite grains and discontinuous quartz lenses in the upper part of FA2 suggests that siliciclastic and carbonate sediments accumulated simultaneously without inhibiting in -situ carbonate formation, despite the influx of terrigenous siliciclastic material (Flügel & Munnecke, Reference Flügel and Munnecke2010; Jafarian et al. Reference Jafarian, Kleipool, Scheibner, Blomeier and Reijmer2017; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017; Riaz et al. Reference Riaz, Bhat, Latif, Zafar and Ghazi2022). The occurrence of sharp-based thin sandstone lenses within the calcareous shale beds suggests frequent amalgamation of episodic storm events occurring between the fair-weather wave base and the storm wave base (Chakraborty, Reference Chakraborty2004; Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri2005; El-Azabi & El-Araby, Reference El-Azabi and El-Araby2007).

The calcareous shale interbedded with siliciclastic and carbonate laminae with good to moderate segregation, within this facies association (FA2), indicates bed-to lithofacies-scale strata mixing (Punctuated Mixing), which is identified both macroscopically and microscopically (cf. Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). Simultaneous accumulation of both detrital quartz and calcite grains within an individual lamina of moderately segregated calcareous shale under a microscope indicates bed-scale compositional mixing (In-Situ Mixing) (cf. Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017).

This kind of compositional and strata mixing of the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith points to a low-to-moderate-energy depositional setting in a deep subtidal regime of a middle-to outer-shelf environment (El-Azabi & El-Araby, Reference El-Azabi and El-Araby2007; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018).

4.b.3. Facies association 3 (FA3): Intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate intercalated with calcareous shale and tabular-bedded limestone

Intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate beds, ranging from 30 to 60 cm in thickness, are found in association with FA2 (Figures 2b and 6a). These conglomerate beds are laterally extensive, spanning more than hundreds of metres within the calcareous shale and at some places associated with thin mauve (Figure 6b) to grey-coloured tabular-bedded limestone (Figure 6c). Each bed exhibits a sharp, typically concave-up erosional base, characterized by either deep scouring or undulating erosional relief (Figure 6d). Tabular to platy-shaped, subangular to well-rounded clasts are compositionally identical to the surrounding limestone beds. These intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerates are predominantly sandy matrix-supported, though some are clast-supported. The clast sizes vary from 1 to 50 cm (Figure 6c). They are poorly sorted, massive, and lack internal stratification or grading. The associated mauve-to-grey limestone beds often display wavy laminations (Figure 6e).

Figure 6. (a) Litholog of the intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate horizon associated with FA2 of the transition zone. (b) Field photograph of the intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate associated with thinly bedded calcareous shale and mauve-coloured, tabular-bedded limestone unit. (c) Field photograph of grey, tabular-bedded limestone associated with intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerates. (d) Field photograph of the intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate bed showing an undulatory surface with convex to concave-up erosional bases. (e) Low-angle cross-laminated limestone bed associated with intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerates. (f) Photomicrograph under plane-polarized light showing an intraformational conglomerate composed of pebble-sized micritic limestone intraclasts (Cm) floating within a matrix of medium-to fine-grained siliciclastics and carbonate cement. (g) and (h) Intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate under crossed polars, well-rounded quartz grains, including polycrystalline (Qp) and monocrystalline (Qm) varieties, cemented by microspar to sparry calcite (scale bar for Figure 6g – 250 µm and for Figure 6h – 500 µm).

Petrography of FA3: FA3 is characterized by the presence of pebble-sized intraformational clasts, dispersed within siliciclastic matrix and carbonate cement (calcite with little dolomite) (Figures 6f–h). These intraformational clasts are largely monomineralic, primarily composed of micritic limestone (Figures 6f, h), with few microsparites. Additionally, few intraformational clasts of calcareous shale (Figure 6f) are also observed. The matrix is composed of medium-to fine-grained, poor to moderately sorted detrital grains of monocrystalline and polycrystalline quartz, K-feldspar, plagioclase, microcline, and some chert. The interstitial spaces are filled with calcite cement (Figure 6g). The siliciclastic grains are predominantly well rounded (Figures 6g, h), although subrounded to subangular grains are locally present. Grain boundaries are frequently corroded (Figure 6g) probably due to post-depositional diagenesis. Iron-oxide coatings are commonly observed on quartz grains (Figure 6g). Feldspar grains are generally fresh but often display significant alteration, while detrital mica occurs as isolated flakes (Figure 6g). No evidence of microscopic-scale strata and/or compositional mixing has been observed from this facies association.

4.b.3.a. Depositional environment

The calcareous shale unit associated with the thick intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate deposits signifies deposition from decelerating flows, indicating a low-energy environment (Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018). In contrast, mass-flow carbonate-clast conglomerates point to high-energy events with short-distance transport and strong wave action (Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). Such events were capable of eroding and transporting materials from coastal or shallow-shelf regions to more distal subtidal carbonate environments (Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). The rounding of some intraclasts suggests prolonged turbulence, while the predominantly subangular shapes indicate rapid erosion and deposition in a single event without extensive reworking or abrasion (Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). Storm activity might have played a key role in eroding, reworking, generating, and transporting these intraclasts in subtidal carbonate settings (Kwon et al. Reference Kwon, Chough, Choi and Lee2002; Myrow et al. Reference Myrow, Tice, Archuleta, Clark, Taylor and Ripperdan2004; Bayet-Goll et al. Reference Bayet-Goll, Chen, Moussavi-Harami and Mahboubi2015; Wright & Cherns, Reference Wright and Cherns2016; Wang et al. Reference Wang, La Croix, Wang, Guo and Ren2019; Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). Alternatively, the absence of combined-flow-generated structures in associated calcareous shale and thin limestone beds, along with lateral persistence of these intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerate beds for tens of kilometres, indicates tsunami-induced wave action. This process could also be responsible for scouring and reworking these intraformational clasts in a ramp setting (Pratt, Reference Pratt2001, Reference Pratt2002; Pratt & Bordonaro, Reference Pratt and Bordonaro2007; Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021).

The interbedding of FA2 with FA3 also provides strong evidence of sporadic, storm-driven sedimentation (Brett, Reference Brett1983). The sheet-like intraformational carbonate-clast conglomerates, along with calcareous shale and limestone beds, resemble characteristic deposits found in base-of-slope carbonate platform margin successions (Cook, Reference Cook, Doyle and Pilkey1979; Cook & Mullins, Reference Cook, Mullins, Scholle, Bebout and Moore1983; Mukhopadhyay et al. Reference Mukhopadhyay, Chaudhuri and Chanda1997).

4.c. Narji Limestone

The transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith gradually changes into the 140 m-thick Narji Limestone, laterally persistent over few tens of kilometres (Figure 2a).

The lower approximately 35 m of the Narji Limestone is composed of whitish-grey flaggy limestone with 8–30 cm-thick beds and is characterized by the presence of syn-sedimentary deformation structures (SSDS, Figure 3i), sand lenses (1–2 cm in amplitude and 2–7 cm in wavelength, Figure 3j) and sedimentary dykes (mainly made up of siliciclastic grains) (2–5 cm wide and 5–20 cm in height, Figure 3i). The proportion of sand lenses increases upwards in the succession. The oblique to vertically oriented sedimentary dykes frequently bifurcate, converge and interconnect within limestone beds. Discordant carbonate-clast-supported breccia bodies (7 to 40 cm) are also observed. The carbonate clasts in breccia bodies range from pebble to cobble size and angular to subangular in shape (Figure 3k), often associated with sedimentary dykes. At some places, plane-parallel to wavy laminations (2–3 cm thick) and low-angle cross-stratification (1–5 cm thick) are present. However, in most areas, these wavy laminations are syn-sedimentary deformed (Figure 3i).

The whitish-grey limestone transitions to grey limestone beds (5–40 cm thick) with an overall thickness of approximately 17 m. The grey flaggy limestone beds are characterized by combined-flow ripple-laminated structures, hummocky and swaley cross-stratification (4–5 cm amplitude, 5–14 cm wavelength), small trough cross-stratifications (3–4 cm thick), and wavy to low-angle laminations (1–2 cm thick, Figure 3l). Stylolites appear as bed-parallel or transverse/oblique features.

The grey, flaggy limestone transitions into massive, greyish-black limestone beds (7–55 cm thick) with a total thickness of approximately 3 m. These greyish-black limestone beds are characterized by bed-parallel and oblique stylolites (Figure 3m) and near absence of primary sedimentary structures and terrigenous input.

The uppermost 70–100 m comprises black limestone (5–20 cm beds) with plane-parallel laminations (Figure 3n) with marl interlayers (few millimetres thick). The laterally extensive marl–micritic rhythmites serve as a key marker horizon for basin-wide correlation of the Narji Formation and are characterized by the presence of abundant pyrite cubes.

4.c.1. Depositional environment

The lower part of the Narji Limestone is characterized by sand lenses, syn-sedimentary deformed wavy laminations, and low-angle cross-stratifications, indicating deposition in a moderate-to high-energy intertidal environment. In this setting, variations in sediment supply appear to have exerted a stronger control than abrupt changes in water depth (Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). The predominance of SSDS likely resulted from upward injection of thixotropically liquidized clayey carbonate sediments as a result of application of external forces (Gruszka & Van Loon, Reference Gruszka and van Loon2007; García-Tortosa et al. Reference García-Tortosa, Alfaro, Gibert and Scott2011; Chen & Lee, Reference Chen and Lee2013). Steep sedimentary dykes suggest upward escape of liquidized sediment (Rossetti, Reference Rossetti1999; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Van Loon, Han and Chough2009b; Chen & Lee, Reference Chen and Lee2013), while discordant breccia bodies indicate liquefaction and fluidization of weakly cemented carbonates (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Van Loon, Han and Chough2009b, Reference Chen, Chough, Han and Lee2011). SSDS are typically localized, contrasting with large-scale deformations caused by earthquakes or rapid sea-level changes (Sims, Reference Sims, Pavoni and Green1975; Hilbrecht, Reference Hilbrecht1989; Spence & Tucker, Reference Spence and Tucker1997; Wheeler, Reference Wheeler, Ettensohn, Rast and Brett2002; Alfaro et al. Reference Alfaro, Gibert, Moretti, García-Tortosa, Sanz de Galdeano, Galindo-Zaldívar and López-Garrido2010; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Chough, Han and Lee2011).

Stratigraphically upwards, combined flow generated low-angle cross-stratified and hummocky cross-stratified limestone, indicative of high-energy storm-generated flows in a carbonate-depositing shelf environment (Dot & Bourgeois, Reference Dott and Bourgeois1982; Duke, Reference Duke1985; Duke et al. Reference Duke, Arnott and Cheel1991; Myrow & Southard, Reference Myrow and Southard1991; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Słowakiewicz, Tucker, Pancost and Bhattacharya2016). The close association of hummocky cross-stratification, combined-flow structures and wavy laminations in limestone beds indicates a shallow-subtidal regime with occasional storm action up to intermediate depths (Chaudhuri, Reference Chaudhuri2005; Van den Berg et al. Reference Van den Berg, Boersma and Van Gelder2007; Dalrymple, Reference Dalrymple, James and Dalrymple2010; Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). Transitioning to dark grey, flaggy limestones with massive to horizontally laminated beds, and absence of terrigenous input, suggest deposition below storm wave base under low-energy deep subtidal environment (Roy et al. Reference Roy, Chakrabarti and Shome2020).

The uppermost part of the Narji Limestone – featuring marl–micrite rhythmites – indicates low-energy sedimentation in deeper anoxic water (outer shelf) and in warm (tropical–subtropical) climatic condition that probably indicate stabilization of the carbonate platform (Schieber, Reference Schieber1989; Elrick & Snider, Reference Elrick and Snider2002; Westphal & Munnecke, Reference Westphal and Munnecke2003; Elrick & Hinnov, Reference Elrick and Hinnov2007; Westphal et al. Reference Westphal, Munnecke, Böhm and Bornholdt2008; Westphal et al. Reference Westphal, Halfar and Freiwald2010; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Słowakiewicz, Tucker, Pancost and Bhattacharya2016; De Kock et al. Reference De Kock, Malatji, Wabo, Mukhopadhyay, Banerjee and Maré2024). The presence of pyrite within the marl–micrite rhythmites indicates low-reactive iron concentration and higher diagenetic temperatures (60–80°C), which facilitated its formation during later-stage diagenesis (Canfield, Reference Canfield1989; Raiswell & Canfield, Reference Raiswell and Canfield1998; Machel, Reference Machel2001; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Chen, Zhang, Lü, Wang, Liao, Shi, Tang and Xie2019).

5. Discussion

5.a. Depositional model of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin

The 10 m-thick, laterally extensive mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit records the complex interplay between relative sea-level fluctuation and sediment supply (Haines, Reference Haines1988; Saylor, Reference Saylor2003; Dibenedetto & Grotzinger, Reference Dibenedetto and Grotzinger2005; Ferronatto et al. Reference Ferronatto, dos Santos Scherer, Drago, Rodrigues, de Souza, dos Reis, Bállico, Kifumbi and Cazarin2021). Here, we propose a paleogeographic reconstruction of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin that evolved from a siliciclastic depositional system to a stable carbonate platform through this transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith.

The Banaganapalle Formation represents a siliciclastic depositional system initiated as an alluvial fan to fan-delta system and likely linked to basin-opening faults during the active rifting phase (Saha & Tripathy, Reference Saha and Tripathy2012a; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012; Saha & Patranabis-Deb, Reference Saha and Patranabis-Deb2014) (Figure 7a), probably around 1.3 to 1.1. Ga (Joy et al. Reference Joy, Jelsma, Preston and Kota2012). This fan-delta system gradually transitioned into a shallow-marine coastal system that may indicate a decrease in basin slope and a reduction in sediment supply (Figure 7b). This change in paleogeography is typically consistent with a shift from deltaic to linear shallow clastic coastal system in intracratonic rift settings (Posamentier & Allen, Reference Posamentier and Allen1999; Gawthorpe & Leeder, Reference Gawthorpe and Leeder2000; Catuneanu et al. Reference Catuneanu, Galloway, Kendall, Miall, Posamentier, Strasser and Tucker2011).

Figure 7. Depositional models illustrating palaeogeographical reconstructions and the distribution of lithofacies associations: (a) and (b) The siliciclastic depositional systems of the Banaganapalle Formation. (c) The transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic system. (d) Development of a carbonate platform (Narji Limestone).

The parallel-laminated clayey siltstone beds, deposited in offshore environments, overlie the shallow-marine upper shoreface deposits (Figure 7b) of the Banaganapalle Formation succeeded by a sharp transgressive lag surface (Figure 2a). This basin-wide offshore deposit is suggestive of a rapid relative sea-level rise, leading to a basin-wide marine transgression (Meng et al. Reference Meng, Wei, Qu and Ma2011). High and stable sea level led to the formation of intercalated sharp-based glauconitic sandstone beds (1–15 cm) within plane-parallel-laminated clayey siltstone, suggesting an inner-to middle-shelf environment (Odin & Matter, Reference Odin and Matter1981). This marks the initiation of the transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic deposit (Figure 7c). Stratigraphically overlying the calcareous shale–siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit within this transitional zone indicates concurrent carbonate precipitation in a low-energy setting with gradual sea-level rise (Flügel & Munnecke, Reference Flügel and Munnecke2010; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018). The progressive upward increase in thin limestone beds and decrease in fine-grained sandstone laminae suggest a deeper subtidal setting and a transition from middle-to outer-shelf environment (El-Azabi & El-Araby, Reference El-Azabi and El-Araby2007; Li & Schieber, Reference Li and Schieber2018) (Figure 7c). The interbedding of laterally extensive, sharp-based, erosive, intraformational flat-pebble carbonate-clast conglomerates with calcareous shale and thin lime mudstone is a characteristic litho-assemblage of this Proterozoic mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith in the Kurnool sub-basin. This litho-assemblage indicates low-energy suspension settling of calcareous shale with concomitant carbonate precipitation interrupted by high-energy events that deposited these carbonate-clast conglomerates. However, the absence of hummocky or swaley cross-stratification and combined-flow structures in the associated calcareous shale and thin limestone units suggests minimal storm influence. Deposition of the flat-pebble carbonate-clast conglomerates probably resulted from episodic tsunami-induced wave action – that may reflect syn-depositional basin tectonics – eroding the underlying lime mudstone beds (Pratt & Bordonaro, Reference Pratt and Bordonaro2007; Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). The syn-depositional basin tectonics may reflect reactivation of the existing fault systems within the intracratonic Kurnool sub-basin (Saha & Patranabis Deb, Reference Saha and Patranabis-Deb2014) that likely triggered the tsunami events. This reactivation of the faults may also have caused subsidence, leading to a basin-wide gradual relative sea-level rise (Patranabis Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012) reflected by the presence of the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith.

In the overlying Narji Limestone, wavy-laminated to low-angle cross-laminated units with numerous sand lenses indicate a re-established shallow-marine intertidal setting (Figure 7d) (Pratt & Rule, Reference Pratt and Rule2021). The presence of near-vertical sedimentary dykes, discordant limestone breccia bodies and soft-sediment deformation structures suggests multiple triggering mechanisms. The triggering mechanisms could be either endogenic factors such as storm waves, floods, rapid sedimentation, and sea-level changes, or exogenic factors like tsunamis, earthquakes, and fault reactivation (Allen, Reference Allen1986; Jones & Omoto, Reference Jones and Omoto2000; Owen et al. Reference Owen and Moretti2011). However, these syn-sedimentary deformation structures are only found within the shallow-marine intertidal deposit of the lowermost part of the Narji Limestone. Therefore, the horizon-specific, laterally continuous, and localized nature suggests that the SSDS formed mainly due to storm-induced loading and strong wave action (Owen et al. Reference Owen and Moretti2011; Chen & Lee, Reference Chen and Lee2013). Upward in the sequence, combined-flow laminated (1–2 cm) and hummocky cross-stratified (5–14 cm wavelength) flaggy limestone again indicates storm-driven flow in a subtidal environment during gradual sea-level rise (Dalrymple, Reference Dalrymple, James and Dalrymple2010; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Słowakiewicz, Tucker, Pancost and Bhattacharya2016). Stabilization of the carbonate platform (Figure 7d) is marked by laterally extensive, sand-free, black marl–micrite rhythmites (Pomar, Reference Pomar and V2020) across the Kurnool sub-basin. The presence of black-coloured, thick and regionally extensive deeper water marl–micrite rhythmites of the Narji Limestone suggests a relative sea-level rise, leading to a marine transgression and a drowning event in the Kurnool sub-basin (Aigner, Reference Aigner1985; Gomez & Astini, Reference Gomez and Astini2015).

5.b. Variability and causes of mixing in the transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit

Mixed siliciclastic–carbonate sediments form in shelf settings through various complex sedimentological processes (Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). Such deposits typically occur on shallow-marine carbonate platforms and shelves, where siliciclastic input may result from storm activity, tidal currents, fluvial discharge, gravity-driven flows, or reworking and erosion of hinterland and shoreline sediments (Gillespie & Nelson, Reference Gillespie, Nelson, James and Clarke1987; Yose & Heller, Reference Yose and Heller1989; Dorsey & Kidwell, Reference Dorsey and Kidwell1999; Chiarella & Longhitano, Reference Chiarella and Longhitano2012; Chiarella et al. 2012; Smrzka et al. Reference Smrzka, Kuzel, Chiarella, Joachimski, Vandyk, Kettler and Le Heron2022). In the study area, the transition zone shifts from clayey siltstone with glauconitic sandstone interbeds to mixed siliciclastic–carbonate deposits, with an increase in carbonate proportion stratigraphically upwards.

Macroscopic and field observations reveal cm-to dm-scale interbedding of calcareous shale and glauconite-bearing quartzo-feldspathic sandstone, along with intermittent limestone beds (a few mm to 2 cm thick), indicating lithofacies-scale strata mixing (cf. Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017) (Figures 5b, k, l). Petrographic analysis also reveals the strata mixing at bed scale, with well-segregated (Figure 5d) to poorly segregated (Figure 5m) alternating µm-to mm-scale lamina of carbonate-rich calcareous shale and quartz-rich siliciclastics. The µm-to mm-thick, quartz-rich siliciclastic layers, at places, form undulating erosive lower bounding surfaces and asymmetric convex-up top surfaces (Figure 5d), locally develop normal to reverse grading (Figure 5g) and occasionally scour into the calcareous shale (Figure 5h). Such features suggest deposition under short-term, high-frequency sea-level fluctuations – from highstand (formation of carbonate-rich calcareous shale layers) to lowstand (quartz-rich siliciclastic layers) – punctuated by episodic high-energy events (e.g., storms) and/or gravity-driven processes in an outer-to middle-shelf setting (Wilson, Reference Wilson1967; McNeill et al. Reference McNeill, Cunningham, Guertin and Anselmetti2004; Halfar et al. Reference Halfar, Ingle and Godinez-Orta2004). Importantly, these observations demonstrate that strata mixing is not only limited to the lithofacies scale (Figures 5b, k, l) but also occurs at the microscopic scale (Figures 5d, g), providing the first documentation of such microscopic-scale strata mixing processes from this Proterozoic succession in southern India. This type of lithofacies-scale strata mixing in a deep subtidal shelf setting reflects Punctuated Mixing, wherein carbonate mud accumulated as background sediment, while high-energy events like storms eroded fine-grained siliciclastics from nearshore and redeposited it as hybrid deposits alongside carbonates (Tucker, Reference Tucker, Einsele and Seilacher1982; Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017).

Sub-rounded to well-rounded calcite grains are observed (Figures 5n, o) alongside thin, discontinuous lenses of µm-to mm-thin fine-grained quartz layers and discrete subangular quartz grains are found floating within the calcareous shale (Figures 5m–o), which indicate the bed-scale compositional mixing within mm-thick laminae (Figures 5e, f, m, n, o, p). At the laminae scale, this type of bed-scale compositional mixing indicates In-Situ Mixing (Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017) and suggests that sediment accumulation is dependent both on the siliciclastic transport and in -situ carbonate precipitation (Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Muto2009; Chiarella, Reference Chiarella2011, Reference Chiarella, Dalrymple and James2016; Longhitano et al. Reference Longhitano, Chiarella, Di Stefano, Messina, Sabato and Tropeano2012; Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017). The In-Situ Mixing refers to the deposition of siliciclastic and carbonate sediments contemporaneously within the same environment, without inhibiting in situ carbonate formation, resulting in locally developed mixed layers. The degree of segregation between siliciclastic input and carbonate precipitation within the in -situ mixed layer varies with bathymetry of the ambient shelf setting and rate of in -situ carbonate precipitation and sediment supply, forming laminae or laminae sets accordingly (cf. Chiarella & Longhitano, Reference Chiarella and Longhitano2012). In the present study, the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit shows a change in segregation stratigraphically upwards from good (Figure 5d) to moderate (Figure 5m), indicating a gradual transition from outer-to middle-shelf environments (Mount, Reference Mount1984; Chiarella & Longhitano, Reference Chiarella and Longhitano2012).

This study documents the coexistence of compositional and strata mixing, where bed-scale compositional mixing (In-Situ Mixing) forms an integral part of bed-to lithofacies-scale strata mixing (Punctuated Mixing) within the mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith unit. This Mesoproterozoic outer-to middle-shelf mixed heterolithic deposit records the transition from the nearshore Banaganapalle siliciclastic to the shallow-to-deep marine Narji Limestone. Thus, this study also confirms that siliciclastic and carbonate end-members do not pertain to two different realms, but they are part of a depositional continuum (sensu Doyle & Roberts, Reference Doyle and Roberts1983), with strata mixing governed by the balance between terrigenous supply and carbonate productivity (Chiarella et al. Reference Chiarella, Longhitano and Tropeano2017).

5.c. Sequence stratigraphic record

A paleo sea-level history of the lower part of the Kurnool sub-basin has been reconstructed here by studying lithostratigraphy and facies distribution (Figures 7a–d and 8). The initiation of the Banaganapalle Formation is characterized by an alluvial fan to fan-delta system, representing a highstand systems tract (HST), which is typically associated with the progradation of a deltaic system (Posamentier & Allen, Reference Posamentier and Allen1999; Catuneanu et al. Reference Catuneanu, Galloway, Kendall, Miall, Posamentier, Strasser and Tucker2011). This progradational package initially transitions into middle-to lower-shoreface deposits, indicating retrogradational stacking as the rate of sediment supply is slower than accommodation; this retrogradational package then gradually transitions into a shallow-marine linear coastal system, where the entire marine succession coarsens upwards from lower to upper shoreface to foreshore environment. The foreshore then gradually transitions to tidal flat deposits, followed by aeolian deposits due to a relative sea-level fall during lowstand. This change represents that a progradational stacking with the rate of sediment supply is higher than accommodation space. Upward in the succession, the aeolian package again gradually grades into upper shoreface deposits due to a relative rise in sea level, indicating late lowstand and early transgression stage. This upper shoreface deposit is followed by a sharp transgressive lag surface, indicating a rise in relative sea level associated with basin subsidence.

Figure 8. Tectono-sedimentary evolutionary model of the lower part of the Kurnool Group. Shades in the column of water depth curve indicate feasible ranges of depositional environments. The rate of change of relative sea-level controlled by tectonics, sedimentation rate, and water depth are linked to one another and plotted as per change of lithofacies.

This rise in relative sea level leads to the deposition of plane-parallel-laminated clayey siltstone. The sharp transition from wave-agitated foreshore–shoreface deposits to below-wave-base clayey siltstone deposits indicates that the association was deposited within a transgressive systems tract (TST) during basin expansion (cf. Mukhopadhyay et al. Reference Mukhopadhyay, Chaudhuri and Chanda1997). The occurrence of the parallel-laminated clayey siltstone interbedded with thin glauconitic sandstone beds marks the initiation of the transitional zone from the Banaganapalle siliciclastic to the Narji Limestone. Glauconitization is one of the key characteristics of condensed zone sediments and can thereby be considered as typical of TST (Loutit et al. Reference Loutit, Hardenbol, Vail, Baum and Wilgus1988; Haq, Reference Haq and Macdonald1991; Amorosi, Reference Amorosi1995, Reference Amorosi1997; Amorosi & Centineo, Reference Amorosi and Centineo1997). The low rate of sedimentation in the Proterozoic epeiric seas made authigenic glauconite formation possible, even under HST conditions (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Jeevankumar and Eriksson2008). In the present study, the presence of glauconite-rich sandstone bodies within thin interval of yellow clayey siltstone, atop a thick siliciclastic deposition, may be associated with maximum accommodation space during transgression, compatible with a maximum flooding surface (MFS) (Gomez & Astini, Reference Gomez and Astini2015). Therefore, condensation during maximum flooding allowed for the authigenesis of the glauconite beds (Loutit et al. Reference Loutit, Hardenbol, Vail, Baum and Wilgus1988). This system overlies the TST and is characterized by a rapid cessation of coarse siliciclastic input, and a transition from glauconite-rich facies to calcareous shale-rich heterolith. Rare amalgamation of storm beds, as indicated by the presence of thin streaks of very fine-to fine-grained sandstone within the calcareous shale unit in the upper part of the transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith zone, suggests deposition in a distal middle-shelf to outer-shelf environment during a HST with a very low sedimentation rate. Such low sedimentation rates are characteristic of open shelves in Precambrian epeiric sea settings (Banerjee et al. Reference Banerjee, Jeevankumar and Eriksson2008).

The progressive upward transition from the transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolith to the open-marine, storm-influenced shallow-subtidal facies of the Narji Limestone indicates an increase in accommodation space. This pattern represents an acceleration in the relative sea-level rise (Gomez & Astini, Reference Gomez and Astini2015). A rapid transgression led to the formation of a second TST, resulting in the drowning of the platform and the deposition of approximately 70–100 m thick, pyrite-bearing black limestone, presumably in an anoxic, quite deep-water system. Development of this deep-water basinal facies association throughout the upper part of the Narji Limestone in the Kurnool sub-basin suggests a major transgression and formation of a very wide, deep, low-energy marine basin with oxygen deficiency (cf. Galfetti et al. Reference Galfetti, Bucher, Martini, Hochuli, Weissert, Crasquin-Soleau, Brayard, Goudemand, Brühwiler and Guodun2008).

5.d. Correlation amongst mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heteroliths from other South Indian Purana basins

Sedimentary successions within the Mesoproterozoic basins of Peninsular India exhibit characteristic fining-upward trends from basal conglomerates and coarse sandstones to overlying finer clastics and carbonates, reflecting signatures of transgressive events associated with rising sea levels (Chaudhuri et al. Reference Chaudhuri, Mukhopadhyay, Deb and Chanda1999; Patranabis-Deb et al. Reference Patranabis-Deb, Saha and Tripathy2012). In the Kurnool sub-basin, an approximately 10 m-thick, laterally extensive transitional mixed siliciclastic–carbonate heterolithic unit marks the onset of a major transgressive sequence between the basal siliciclastic Banaganapalle Formation and the overlying Narji Limestone.