English Catholics who sailed on Spanish ships are rarely discussed in studies of maritime history and religious emigration during the Tudor period. The work of Paula Martin stands as a notable exception, focusing on Englishmen who served in the Spanish Armada of 1588 as entretenidos (unattached officers) and aventureros (gentlemen adventurers).Footnote 1 However, broader research on English mariners in Spanish service has yet to be fully developed. This article seeks to contribute to the field by presenting English Catholics on Spanish vessels as a complex seafaring group. The article will highlight their career trajectories, their relations with the Spanish authorities, and their collaboration with English priests in exile. In doing so, it will argue that whilst their numerical presence was not large, their activities are revealing of the complex nature of Anglo-Spanish connections. It will address five key issues relating to this group of seamen. Firstly, it will explore Sir Thomas Copley’s privateering enterprise, which strengthened Spanish maritime defence in the waters of the Low Countries. Secondly, English seamen within the Spanish navy will be considered. Thirdly, their motivation, whether based on individual inspiration or collective identity, will be examined. Fourthly, the issues surrounding religious activity on Spanish ships and collaboration between clergy and sailors will be covered, and finally, the points of tension between English mariners and Spanish authorities, as well as the means by which the former left Spanish service, will be considered.

Studies on Catholic exiles often focus on religious and political reasons for migration from England.Footnote 2 The controversial case of the sea adventurer and Catholic Thomas Stucley (c. 1520–1578), who fled to Spain in April 1570 with significant political ambitions to liberate Ireland, is well known.Footnote 3 Mercantile and trade interests have also been cited as reasons for migration to Spain.Footnote 4 English sailors captured by the Inquisition often converted to Catholicism to avoid penalties, as was the case with sailors from John Hawkins’ ships, who were captured and settled in New Spain in 1569.Footnote 5 According to Thomas O’Connor, the conversion of prisoners of war was, in many cases, nominal, and only after living in Spain for many years did they absorb the Catholic culture.Footnote 6 Through an examination of sailors’ circumstances, this study reveals additional causes and reasons for English Catholics’ involvement in Spanish naval service, including religious motivations, military or family ties, and impressment from prison or galleys.

Recent scholarship has asserted that the number of English Catholic exiles in Europe was small,Footnote 7 and the presence of English sailors in the Spanish fleet was similarly limited. However, they were relatively more numerous in the Spanish Netherlands during the 1570s, likely due to active recruitment organised by the exile Sir Thomas Copley (1532–1584). Later, the English were appointed to various regional armadas and employed in one-off expeditions, but were prohibited from sailing to the West Indies. Elements of the mariners’ religious life not only reflect the specifics of religious practices aboard but also highlight the collaboration between English sailors and English priests. While the collaboration between priests and laypeople in England has been the subject of several studies, primarily focusing on harbouring priests ashore,Footnote 8 some issues related to conveying priests to England have also been explored.Footnote 9 However, historians rarely paid attention to the collaboration between English sailors and Catholic clergy. An exploration of the challenges faced by English sailors in Spain and Spanish-controlled territories, as well as their reasons for departing from Spanish service, connects with the questions raised by Anne R. Throckmorton regarding all English Catholic exiles.Footnote 10 This article demonstrates that English sailors encountered the same difficulties as other exiles, including poverty, suspicion, and discrimination, though these challenges were experienced within their distinct maritime context.

Working with the Sources

This research draws on material preserved in Spanish and British archives.Footnote 11 Both Spanish and English sources contain inherent biases—the Spanish sources portraying Englishmen and Protestants unfavourably, and the English sources reflecting hostility towards Catholics, particularly during the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604). Some of these materials, therefore, are problematic when used in isolation. One example is the correspondence of William Cecil (1520/21–1598). As Francis Edwards has demonstrated, Cecil and his agents often distorted reality to present Catholics in the worst possible light in order to influence the Queen’s policy.Footnote 12 Consequently, evidence must be treated with caution and this article aims to carefully contextualise the sources and employ them in conjunction with other pieces of evidence.

Spanish documents in this study are mostly sourced from the Council of War, including reports from officials and petitions from English mariners requesting payment. In the 1580s, the Council was staffed by professional councillors and secretaries, becoming more expert and efficient, though it still operated slowly due to a lack of personnel.Footnote 13 The Council’s internal documents provide a valuable source of information on English seamen’s careers in the Spanish naval forces and army. While errors in its documentation are occasional, these can be cross-checked by comparing them with similar information from other Council records.

Before proceeding further, it is also necessary to clarify the issue of name translation in the early modern period. In an age when phonetic transcription often took precedence over consistent orthography—indeed, before standardised spelling existed—a wide range of variant forms could be recorded for the same individual. For example, Captain Edward Cripps may be found in English records as Cripes or Cripse, and in Spanish as Eduardo Cripsio, Crispio, or Crispeo. Similarly, the Spanish naval commander Pedro de Zubiaur is variously recorded as Cubiaur, Cubiaure, or Subiauer; while another commander, Antonio de Urquiola, appears as Orquiola, Orqueollo, or Voquiola. This article will adopt the standard modern form of each name where one exists. Otherwise, the version most frequently found in the relevant native-language sources has been used. One notable exception is the name of Robert Persons, S.J., (1546–1610) which appears in both early modern and modern usage as either Persons or Parsons. While both forms have historical precedent, this study employs the former, as it aligns more closely with how he styled himself—Roberto Personio—in Spanish spelling.

Sir Thomas Copley’s enterprise in the Low Countries

The precise number of English seamen who migrated to Spain and its controlled territories remains unknown, but some general parameters can be established. Hundreds of English seamen entered Spanish service, including some with their own ships, when Spain sought to secure control over the rebellious Low Countries. Between 1568 and 1571, the English government radicalised its policy towards Catholics in response to the growing rivalry with Spain, rebellions in northern England and Ireland, the Ridolfi Plot, and the Pope’s excommunication of Elizabeth I.Footnote 14 Nine pieces of major anti-Catholic legislation were enacted between 1570 and 1585.Footnote 15 For example, one act, issued in 1571, forbade reconciliation with the Catholic Church and classified Roman Catholicism as an act of political disloyalty.Footnote 16 It is no surprise that some English Catholics chose exile in the Netherlands, where they could join Spanish forces. The earliest evidence of this influx dates to 1574, when Richard Bingham (1527/28–1599), Commander of the Royal Navy, informed William Cecil that two masters, James Ramson and John Young, each with a crew of one hundred mariners, had offered their services to the King of Spain.Footnote 17 Around the same time, Cecil was also informed of an offer made to Sir Thomas Copley, an English Catholic exile recruiting for the Spanish army and navy: the mariner Avery Philips had offered ‘to bring over 300 mariners and 12 ships.’Footnote 18 Meanwhile, Sir John Smith wrote about ‘a gentleman of great worship in England who is ready … to send him [Copley] … eight hundred mariners and who had bought the Mary Rose, one of the Queen’s ships.’Footnote 19 Smith himself joined Copley’s fleet, possibly on his own ship.Footnote 20 Despite concerns about conflicts between English mariners and German mercenaries in one of the Spanish camps, Thomas Copley wrote enthusiastically to Philip II in June 1574 about the arrival of many English Catholics.Footnote 21

It was not only committed Catholics who sought a place on Copley’s ships. In 1574, William Cecil was informed that Englishmen who arrived in the Low Countries to serve the Spaniards who were not Catholics were sent away, including mariner Avery Phillips, who ‘was no Catholic and therefore was not to be enlisted.’Footnote 22 Not all sailors passed the entry examination, which required every sailor to confess his sins and take communion before joining a Spanish ship.Footnote 23 Some entered Spanish naval service in the 1570s not because of genuine Catholic beliefs, but rather because they were adventurers seeking financial gain. Technically, this service was a business arrangement with the Spanish King, who retained one-tenth of the gained prizes.Footnote 24 Delays in payment of shares from the booty were not always tolerated, suggesting seamen’s material interests rather than spiritual motivations. One English report stated that 80 English mariners began to demand passports to leave Copley’s privateers in Spanish service, as they had only been paid for two months. Additionally, one sea officer was reluctant to return to England because he had committed piracy.Footnote 25

The number of English mariners serving in foreign forces became so significant in the 1570s that Elizabeth I issued a proclamation on 26 October 1575. This prohibited English mariners from serving in France and the Low Countries, as English soldiers and mariners were robbing English ships.Footnote 26 However, this proclamation did not achieve the desired outcome, at least in the Spanish Netherlands. Between 1574 and 1580, there was a notable influx of English mariners into Spanish service in the Netherlands, coinciding with Sir Thomas Copley’s tenure there. The period was particularly conducive to such activities, as the Wars of Religion in France and the Dutch Revolt against Spain extended to the seas, drawing many English seamen into the conflicts. While a multinational Protestant force of privateers operated in the Channel, a Catholic fleet was also active.Footnote 27 Flanders proved to be particularly fertile ground for recruiting English soldiers and mariners. Although the majority joined the Protestant forces of the Dutch rebels led by William of Orange, many others enlisted with the Spanish contingent. Their motivations varied, ranging from economic and religious factors to a military interest in gaining practical experience. Notably, from 1572 onwards, the Elizabethan government covertly dispatched troops to the Low Countries disguised as volunteers.Footnote 28

In 1574, Copley formally took up Spanish military service with the task of recruiting soldiers and, about this time, received Letters of Marque against ships of Hollanders and Zealanders. He appointed English deputies within these letters to fight the Dutch rebels at sea.Footnote 29 Therefore, his active organisational role must have been one of the crucial factors making this influx of English mariners possible. They arrived at a point when the Spanish command was struggling to create a permanent squadron in the waters of the Netherlands to counter the Sea Beggars, who had captured Brill and Flushing in 1572. The Armada of Flanders was only in its formative phase and would not operate till 1583, when the Spaniards recaptured Dunkirk and established the first admiralty of the Spanish Netherlands there. An attempt to create a squadron of private merchant ships at Santander from 1573 to 1574 failed due to a lack of finances and a typhus outbreak.Footnote 30 Therefore, Copley’s international privateers filled a gap in the Spanish maritime defence against the Sea Beggars.

Although Copley’s maritime activity has been omitted or only briefly mentioned in studies on his life, his work for Spanish forces requires further consideration.Footnote 31 He was a potentially attractive recruiter for Catholics loyal to the Queen and for those who were willing to oppose her. Copley aimed to present his work as being of benefit for both Elizabeth I and Philip II, claiming that in the Netherlands, he was helping to suppress rebels who fought against their monarch, in Copley’s words, ‘their naturall and lawful king.’Footnote 32 However, his efforts were not rewarded by the Queen and her ministers despite his regular claims that he was serving foreign princes only for reasons of financial necessity. His activity was not in line with English foreign policy, which supported the Dutch rebels. Early in 1580, Thomas Copley left the Netherlands for Paris, probably having resigned from his position and pension.Footnote 33 By this point, his naval service was no longer needed. In 1580, Spain annexed Portugal, significantly reinforcing its naval presence in the western waters by acquiring Portuguese sailors and galleon-type warships.Footnote 34

English seamen among other nationals

In the 1570s, the presence of numerous foreign privateers, especially English privateers, in service was unusual for the Spanish forces in the Atlantic in this period.Footnote 35 The Spanish naval systemFootnote 36 was traditionally based on national maritime recruitment, which was typical for all large European countries of the time. Relatively large territories allowed countries such as England, France and Spain to be self-sufficient in human resources, unlike smaller maritime nations, such as the Dutch Republic or German city-republics, which had to use international recruitment.Footnote 37 Foreign sailors were recruited in significant numbers only when the domestic supply failed to meet demand. This happened in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries when, exhausted by the Anglo-Spanish war, Spain enlisted many foreigners into its expedition to England in 1597 and to Ireland in 1601.Footnote 38

The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was a natural consequence of tensions that had been building since Elizabeth’s accession. Key factors contributing to the conflict included religious antagonism between Protestant and Catholic regimes, English support for Dom António’s efforts to reclaim Portugal, ongoing confrontation in the Netherlands, English piracy and smuggling and Spain’s rigid control over the western Atlantic and the Pacific, from which it sought to exclude other nations. The war was primarily a naval conflict, with battles occurring in both European and American waters. These included English raids on Lisbon, Cadiz, the Azores, and the West Indies, as well as Spanish armadas sent to the English coast, beginning with the Gran Armada of 1588.Footnote 39

Spanish payment lists issued during the war years 1589 and 1590 indicate that out of 252 positions for sea officers, mariners, soldiers, and gunners, Englishmen were mentioned in only ten positions, comprising 30 individuals. Despite this small number, their presence was greater than that of other foreign recruits (nine positions, featuring 1 Flemish, 2 Portuguese, 1 Venetian, 1 Lombard, 1 Neapolitan, and 5 Irish).Footnote 40 The war with England likely contributed to the higher number of Englishmen recorded in these lists, as the Spaniards required men familiar with the English coastline and capable of interrogating prisoners. For instance, in August 1590, Pedro de Zubiaur (c.1540–1605), a Spanish sea general of the Armada of Biscay, reported from Ferrol that he had received 3 English and Dutch pilots. At this time, Zubiaur’s squadron was actively attacking English and Dutch shipping in the Atlantic, particularly along the Portuguese coast and in the English Channel.Footnote 41 Although the general trend was that English sailors formed only a small minority among foreigners recruited into the Spanish naval service—most being from Catholic countriesFootnote 42—this pattern may have shifted during the Anglo-Spanish War within the regional squadrons operating in European waters, as the evidence above suggests. Spanish ships remained predominantly nationally manned, though they were at times in urgent need of the expertise of English navigators.

There was a strong cultural bias among Elizabethans, including Catholics, against going to Spain. Christopher Highley has outlined their most common fears: they believed that living in Spain would strip them of their Englishness, expose them to alien foodstuffs and a climate deadly to the English-born, and cause them to lose their godly beauty—namely, their pale complexion—under the merciless Spanish sun.Footnote 43 Moreover, the number of Catholics in England was steadily declining, and the remaining Catholic community was increasingly divided over how to negotiate their place in Protestant England. Travel to Spain required financial resources or, in the case of recusants, official permission,Footnote 44 while Spanish suspicion toward the English was yet another deterrent.Footnote 45 Additionally, the low status and poor pay of mariners in Spain further discouraged migration.Footnote 46 Consequently, no essential conditions existed for a large-scale influx of Catholic sailors from England.

The number of Irish refugees in Spanish service was higher due to the ongoing Tudor conquest of their homeland. While most Irishmen enlisted in the land army, some served in various armadas, particularly those operating in the Atlantic.Footnote 47 Martín de Bertendona (1530–1604), a naval general, encouraged the Irish to form nucleus communities, which later became a sort of embryonic marine regiments in locations such as Santander, Ferrol, A Coruña, Vigo, and Lisbon.Footnote 48 The policy of establishing separate Irish regiments probably contributed to their underrepresentation in the Spanish payment lists of soldiers and mariners analysed above. The Spanish never considered creating similar units for English exiles, not only because of their smaller numbers but also due to a general mistrust of them as members of a hostile nation.

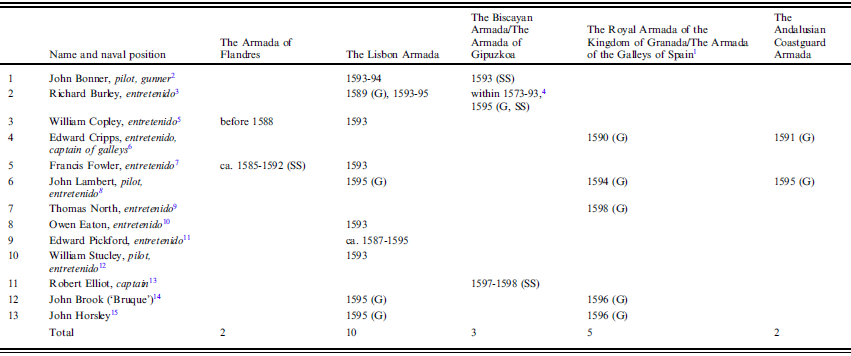

As shown in Table 1 below, the careers of thirteen English seafarers in Spanish service reveal that they were most frequently assigned to the Lisbon Armada. This was the least active of all Spanish regional armadas. The Biscayan Armada and the Armada of Flanders participated in warfare, and the Andalucian Armada mainly escorted West Indian convoys from the Azores to Spain. In contrast, the Lisbon Armada patrolled the Portuguese coast from Cape San Vincent to Cape Finister, linking the Biscayan Armada and the Andalucian Armada.Footnote 49 The assignment of some Englishmen to Lisbon’s coastal Armada might be explained by their lack of deep-sea experience, although others, such as John Bonner, Richard Burley, and John Lambert were expert seamen. For the latter, the placing of loyal English officers in this most passive Armada, under close control of coastal administration, suggests some degree of distrust towards them as representatives of a hostile nation. In 1593, many English and Irish officers in Lisbon were investigated for possible espionage.Footnote 50

Table 1. Careers of English seafaring officers and gunners in Spanish service during the Anglo-Spanish war

(SS) sailing ship, (G) galley; The single year listed in the column refers to the date indicated in the document rather than the full duration of the individual’s service.

1 Esteban Mira Caballos, El sistema naval español en el siglo XVI: Las Armadas del Imperio, in 2001, Revista de Historia Naval nº 74, (1-18) 12.

2 Juan Bonner piloto yngles, 11 de enero de 1589, GyM, leg. 267, fo. 48, AGS; Joan Boner, piloto ingles, GyM, leg. 390, fo. 481, AGS; Joan Boner, 14 de febrero de 1594, GyM, leg. 422, fo. 78, AGS; Juan Boner piloto yngles, 7 de diciembre de 1595, GyM, leg. 447, fo. 93, AGS; Juan Boner, 1596, GyM, leg. 477, fo. 126, AGS.

3 Ricardo Burley ingles, 23 de septiembre de 1593, GyM, leg. 389, fo. 604, AGS; Ricardo Burley cavallero yngles, 12 de noviembre de 1595, leg. 447, fo. 139, AGS.

4 In 1593, Burley stated that he had served the Spanish King in the waters of England and France under various generals for twenty years, after which he was appointed to the galleys of Lisbon. The specific positions in which he served are not identified, but one of them was very likely in the Armada of Biscay under the command of Pedro de Zubiaur. In the same petition, Burley requested a transfer to this squadron, ‘which sails off the coast of France,’ and referred to Zubiaur as a reliable witness to the fact that he had not been raised among the infantry but had spent his entire life at sea, see Ricardo Burley ingles, 23 de septiembre de 1593, GyM, leg. 389, fo. 604, AGS.

5 Guillermo Copley ingles, 20 deciembre de 1590, GyM, leg. 307, fo 204, AGS; Memorial de Guillermo Copley, criado del Rey en Lisboa, 1594, GyM, leg. 415, fo. 317, AGS.

6 A Don Alonzo de Bazan, 10 de mayo de 1599, GyM, leg 302, fo. 131, AGS; Eduardo Cripsio ingles, 16 de mayo de 1590, GyM, leg 299, fo. 47, AGS; Eduardo Cripsio, 27 de febrero de 1589, GyM, leg. 238, fo. 30, AGS; el adelantado de Castilla, 3 de marzo de 1589, GyM, leg 268, fo. 195, AGS; Conde de Santa Gadea, 16 de diciembre de 1591, GyM, leg 319, fo. 213, AGS.

7 Francisco Fouler cavallero yngles, 1595, Consejo y Juntas de Hacienda, 331, AGS; Francisco Fouler yngles, 30 de junio de 1595, Consejo y Juntas de Hacienda, 330, AGS; Relacion de entretenidos ingleses e irlandeses que hay en la armada, 1593, GyM, leg. 393, fo. 238, AGS.

8 Martin de Durango Varaya, 3 de junio de 1595, GyM, leg. 447, fos 164, AGS; Juan Lamberto, piloto, 1595, GyM, leg. 447, fo. 165, AGS; Don Juan da Silva, 2 de febrero de 1595, Lisboa, GyM, leg. 424, fo. 73, AGS; Juan de Cardona, 16 de septiembre de 1595, San Lorenzo, Estado, leg. 2348, AHN.

9 El capitán Thomas Norte ingles, 4 de marzo de 1598, GyM, leg. 530, fo. 343, AGS.

10 El capitan Ioen Eton, cavallero ingles, 24 de noviembre de 1595, Madrid, GyM, leg 438, fo. 110, AGS; Relacion de entretenidos ingleses e irlandeses que hay en la armada, 1593, GyM, leg. 393, fo. 238, AGS.

11 Duarte Picford ingles, 8 de deciembre de 1595, GyM, leg 442, fo. 109, AGS.

12 Relacion de entretenidos ingleses e irlandeses que hay en la armada, 1593, GyM, leg. 393, fo. 238, AGS.

13 Elliot was based in A Coruña, one of the main locations of the Biscayan Armada, suggesting he may have been a member of this regional squadron. However, further evidence is required to confirm this, as he could also have operated as an independent privateer while his ship was in service, see El capitan Roberto Eliot ingles, 13 de marzo de 1598, GyM, leg. 530, fo. 316, AGS.

14 Los pobres ingleses que estan en Galeras de España, 12 de enero de 1596, GyM, leg. 472, fo. 99, AGS.

15 Footnote Ibid .

The table shows a tendency to employ Englishmen in coastal patrolling, but this does not suggest that they did not distinguish themselves in naval campaigns. In 1588, a treasure galleon of the Gran Armada, Nuestra Señora del Rosario, carried at least seven Englishmen.Footnote 51 Some Englishmen also sailed aboard the Gran Armada’s Portuguese galleon San Mateo.Footnote 52 In 1591, William Copley (1565–1643/1644) participated in the capture of the famous English galleon Revenge at Flores Island in the Azores.Footnote 53 Four years later, Richard Burley led a piratical raid with four Spanish galleys on Mount’s Bay, off the Cornish coast, which included a celebration of Mass in the local church.Footnote 54

It appears that the vessels of the Carrera de Indias, travelling between the Americas and Spain, carried more foreigners than the home-based naval squadrons. In 1568, the Casa de la Contratación issued instructions prohibiting its ships from taking more than six foreign sailors each, citing security concerns.Footnote 55 As representatives of hostile nations, the English and the French were rarely found in these merchant flotas and convoying armadas.Footnote 56 The Spanish administration sought to exclude English sailors entirely from the fleets bound for the West Indies. During the Anglo-Spanish War, it was repeatedly specified in 1589, 1594, 1598, and 1599 that no Englishmen were among the foreign sailors in these expeditions.Footnote 57 The frequency of such specifications suggests that the issue persisted—despite official efforts, some Englishmen still managed to pass unnoticed into these fleets (for direct evidence, see the letter by Dr Burgos de Paz from 1596, cited below). Nevertheless, English sailors were more present in the home-based Spanish armadas than on trade routes in the West Indies, though they remained a minority in both contexts. Richard Hawkins (c. 1560–1622), a naval officer and privateer, might have exaggerated when, in June 1598, he wrote to the Queen from a Sevillian prison that ‘Of maryners and gunners there is not a shipp w[i]ch is not p[ar]tly fournished w[i]th Flemish and English.”Footnote 58 Captured in a sea battle, Hawkins was still in a Sevillian prison, with limited access to information from the outside world, when he made his assessment.Footnote 59

Discerning Motivation

Mariners who left England to serve Spain at sea held varying degrees of militant Catholic views. Some, such as the pilots John Bonner and John Lambert, the entretenido and Captain Edward Cripps, or the entretenido Richard Burley, pursued long careers in the Spanish navy, assimilating into local Catholic culture. As Thomas O’Connor has pointed out, this cultural immersion was essential to the formation of religious identity.Footnote 60 Pilot John Bonner joined the Spanish navy in Lisbon in 1588 and subsequently took part in the Armada’s crusading campaign, having left his wife and children in Weymouth. They were still living in Weymouth in 1592, while he continued his career in the Spanish fleet.Footnote 61 He remained in service despite not receiving the income he had hoped for. Only in 1597, after a lengthy bureaucratic process, did Bonner receive the payment he had been promised for his work from 19 January 1588 to 24 January 1593.Footnote 62 Perhaps he was driven by strong religious convictions and had already been known as a Catholic, even among Protestants, long before his service with Spain. In 1581, while trading at Portuguese Santos, Brazil, Christopher Hare, a Protestant and the master of the Minion of London, used Bonner’s name to conceal the true identity of his purser, Thomas Griggs, who had ‘misused himself’ in Brazil by participating in Francis Drake’s raid.Footnote 63 In 1580 and 1581, Bonner was a part-owner of the ship Jewell, also known as Falcon, which undertook trading voyages overseas, particularly to Hamburg and the Bay of Biscay.Footnote 64

While Pilot Bonner and seamen like him entered Spanish service individually, others did so in groups, following a military leader. Edward Cripps, Henry Ireland, and Owen Eaton accompanied Colonel Sir William Stanley (1548–1630) in January 1587 when he and his regiment surrendered Deventer to the Spanish army in the Netherlands.Footnote 65 Militant Catholic views may have inspired them either at the time of their initial entry into service or later, through contact with English priests in Spain who promoted military action against Protestant England. For instance, in the Netherlands, Cripps transferred his military allegiance from the Protestant leader Sir Philip Sidney (1554–1586)—who was killed in a skirmish at Zutphen in October 1586—to the Catholic William Stanley at Deventer. Later, in Spain, he closely collaborated with Robert Persons, S.J. According to an English agent’s report, in 1591, Cripps declared that his main intention was to burn English ships.Footnote 66 The relationships between William Stanley and his officers might, in some ways, be compared to those between the Earl of Essex (1565–1601) and his Catholic followers in England, who took part in his naval raids on Cádiz and the Azores and later supported his notorious rebellion in London in 1601. As Dan O’Sullivan highlights, Catholic noblemen were bound to Essex by a culture of honour rooted in traditional chivalric ties.Footnote 67 Nonetheless, some of Stanley’s followers, such as the soldiers John and Owen Salusbury of Rug, later reconsidered their allegiance to Spain and left the Spanish army. In 1596, they joined the Earl of Essex in his attack on Cádiz.Footnote 68

Some Englishmen who served on Spanish ships arrived with their family members, motivated by a sense of familial solidarity. The Pickfords emigrated from Cornwall to Spain in the late 1570s. According to A. L. Rowse, their relocation was triggered by the execution of Cuthbert Mayne in 1577, the first martyred seminary priest.Footnote 69 In December 1595, Edward Pickford declared that he had served in the Spanish armadas for eight years.Footnote 70 Other members of the Pickford family fought in the army of the Portuguese King Sebastian in Africa, participating in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir on 4 August 1578, as well as in the Gran Armada of 1588.Footnote 71 In 1618, a Pickford—described as an ‘old beaten soldier’ and a ‘captain or master of a ship’—transported students from Madrid via San Sebastián to the English seminary at St Omer, France.Footnote 72

In addition, the sons of Catholic immigrants whose fathers took them out of England appear in Spanish records. William Stucley was brought to Spain in 1570 by his father, the well-known sea adventurer and soldier Sir Thomas Stucley, when he was eight years old.Footnote 73 In January 1588, he was enlisted in the Gran Armada under the Marquis of Santa Cruz and, soon after, from July to August, served as a pilot aboard the galleon Rosario in this Armada’s failed expedition to England. In July 1589, he was still in naval service, but by 1593 a Spanish report recorded him as deceased.Footnote 74 Similarly, Sir Thomas Copley of Gatton, Surrey, fled England in 1570, taking his son into exile.Footnote 75 William Copley (1565–1643), who would have been around five years old at the time, later followed a military and naval career.Footnote 76 In 1591, he declared that he had served for ten years, first in Flanders and then in the Armada.Footnote 77

Another group of English mariners in Spanish service was recruited from prisons and galleys on the condition that they convert to Catholicism. Although the Mediterranean regional armadas included most of Spain’s galleys due to the specific nature of warfare in the region, other armadas also employed this type of vessel usually for coastal operations (see Table 1). Ordinary prisoners of war were sentenced to serve on galleys for varying terms, with the possibility of being exchanged. Spain made extensive use of galleys and, like other maritime powers that relied on them, faced a chronic shortage of oarsmen. To meet this demand, not only prisoners of war but also convicts (forzados) and slaves—many of whom were Muslims—were forced to row.Footnote 78 Mariners serving on coast-bound Spanish galleys had more frequent contact with priests than those on ocean-going Spanish vessels, which often sailed without chaplains.Footnote 79 As Fernández-Armesto has suggested, the government was concerned about the spiritual welfare of oarsmen, who were required to confess during Lent and attend Mass. Chaplains played a crucial role in pacifying potentially mutinous rowers and easing the consciences of their overseers.Footnote 80 This was particularly important in the context of religious conflicts—between Catholics and Protestants in the western Atlantic and between Christians and Muslims in the Mediterranean. For prisoners, real or feigned conversion to Catholicism was a common means of escaping forced labour or imprisonment.

In 1591, Robert Persons, the leader of the English Jesuits and founder of English seminaries in Spain, took an active interest in converting and patronising English prisoners. In the winter or early spring of that year, many of the 70 enslaved men on galleys in Puerto de Santa María converted to Catholicism.Footnote 81 In March 1591, Persons wrote from Seville that 90 men and 18 boys had become Catholics while serving on galleys, likely including those in Puerto de Santa María.Footnote 82 That same month, he also received newly converted Englishmen who had been arrested on English ships in Sanlúcar de Barrameda.Footnote 83 In December 1591, two young noblemen, the brothers Tomás and Agustín Strickley, who had been taken from an English flagship, were sent to the seminary in Valladolid to Persons.Footnote 84 Contact between English sailors and Jesuit seminaries in Spain continued beyond Persons’ conversion efforts in 1591. In 1597, the English ship Daisy intercepted a flyboat from Sanlúcar de Barrameda, on which they arrested Robert Allison, a former sailor on Drake’s ship. Allison had been travelling to England from the English seminary in Seville, where he had lived among seminary priests.Footnote 85 Another sailor taken from Drake’s last voyage, Richard Gifford, later confessed that he had voluntarily attended the English seminary in Seville and had spoken there with the Jesuit Edward Walpole (bap. 1560, d. 1637).Footnote 86

It appears that Persons did not usually convert prisoners himself but rather received them after their conversion, providing religious instruction and education. Writing to the King about the converts on the galleys, Persons praised the captain, his officers, and two English chaplains as reliable and active figures in the prisoners’ conversion. He also noted their connection to the regiment of Sir William Stanley, which had surrendered Deventer to the Spaniards in 1587.Footnote 87 In his report to the King on the mass conversions in the galleys at Puerto de Santa María, Martín de Padilla (1540–1602), Count of Santa Gadea, highlighted the role of Captain Edward Cripps and Ensign Henry Ireland.Footnote 88 Both were Stanley’s men, and it is likely that Persons was referring to them in his letter. These English officers promoted Catholicism directly among prisoners, much as Pilot Andrew Facy did later.Footnote 89 In 1598 or earlier, Facy gave an English sailor in a Spanish prison a book of Father Persons’ work, urging him to read it in order to ‘be better resolved, as touching the religion between you and us.’Footnote 90

Religious Activity onboard ship

On Spanish ships, as on English and other European vessels in the sixteenth century, officers’ duties were not separate from religious responsibilities. The captain of the galleys, such as Edward Cripps, was responsible for ensuring that all onboard received the sacraments and for reprimanding or punishing those who blasphemed.Footnote 91 On sailing ships, masters typically conducted religious services themselves.Footnote 92 On Sunday evenings, the master preached in front of an altar adorned with candles and religious images. The crew participated in the service by reciting the Salve Regina, the Litany, the Credo, and the Ave Maria.Footnote 93 English chaplains and officers were not the only ones who could minister to English Catholics or reconcile English captives on Spanish ships. Irish chaplains, such as Richard Burck, also conducted services for both nationalities, as he spoke English.Footnote 94 In 1598, sailor and soldier John Stanley confessed to the English Admiralty that the Catholic emigrant and sea captain Robert Elliot, an English gentleman born in Somerset, had received the sacrament from an Irish bishop.Footnote 95

The presence of priests significantly increased on the large crusading expeditions, which were one-off enterprises organised for a specific purpose. Catholic missionary goals became central during the three Spanish Armadas, which sought to invade England with landing troops and Catholic priests.Footnote 96 As a result, priests were included in substantial numbers on these Armadas, with English priests among them. Three chaplains of English origin were aboard the first Spanish Armada in 1588.Footnote 97 The Armada that departed for England in late October 1596 probably carried nearly 40 seminary priests, ‘the most part of them [being] Englishmen.’Footnote 98 It is likely that several English Jesuits were also aboard the third Armada in 1597.Footnote 99

Clergy and Sailors in Concert

English Jesuits were particularly interested in English sailors for several reasons. While helping a much-neglected group, such as galley slaves, was important, another motivation was also at play. In 1591, Robert Persons, explained to Philip II his intention to transform the converts into a seminary of Catholic soldiers from the enemy nation, which could potentially encourage more Englishmen to serve the Spanish King.Footnote 100 However, this plan was not realised. Philip II rejected an offer from former English galley prisoners to serve him, prompting Persons to complain to Don Juan de Idiaquez, a member of the Council of State.Footnote 101 In 1598, in Naples, Persons returned to the issue of converting English sailors imprisoned on galleys, probably those belonging to the Armada of Naples, another Spanish regional squadron. This time, having abandoned the idea of creating a military seminary, he demanded that the 34 new converts pledge to remain Catholic and return to England.Footnote 102 The aim of this adapted plan was to sustain the Catholic population in England, a population which was potentially crucial in helping either a foreign army or a successful domestic faction to rescue the realm from heresy. For this reason, the Elizabethan Catholic hierarchy did not encourage mass emigration of Catholics from England.Footnote 103

The Spanish authorities, however, were deeply distrustful of the English, especially former prisoners. The tribunal in Seville was sceptical about placing the reconciled Englishmen in monasteries for further religious instruction, as they often used this as a first step to escape.Footnote 104 Specific cases of English sailors’ escapes are recorded in the English State Papers. For instance, in 1598 or 1599, mariner Triamor Diconson was held in Madrid’s prison ‘until, upon pretence of turning Catholic,’ he undertook a pilgrimage to Rome. Once embarked on the pilgrimage, he ‘made himself known as a Protestant and cast away his pilgrim’s habits at Montpellier.’Footnote 105 Similarly, in 1598, mariner Ralph Cantrell, after being captured by the Dunkirkers, was released from prison with a nullified ransom in exchange for service in the Spanish fleet—likely the Armada of Flandres. He later escaped to London from Le Tréport, France.Footnote 106

Nevertheless, English seamen in exile, including former prisoners, were potentially valuable partners for English priests, as they could transport both priests and boys, along with Catholic materials. Due to the efforts of Robert Persons, English colleges were established in Spain and its territories, namely in Valladolid (1589), Seville (1592), and St Omer (1593). Persons also played a role in founding the Irish College in Salamanca (1592) and the Scottish College in Douai (1594).Footnote 107 These institutions became part of a broader network of British Catholic colleges in Europe. They provided a rigorous education to Catholic youths who had secretly left the British Isles, preparing them for ordination to the priesthood. Many of these priests later returned clandestinely to England, Scotland and Ireland to promote Catholicism. As reported by English Jesuits to Philip II in 1594, ‘There are five or six of these seminaries in Rome, Valladolid, Seville, Rheims, Douai, and at St. Omer. From these seminaries have come more than three hundred priests who are living at present in England.’Footnote 108 The claim that nearly 300 seminary priests arrived between 1574 and 1596 is also present in academic studies.Footnote 109 Regarding the longer period, Patrick McGrath and Joy Rowe, using data from Godfrey Anstruther’s dictionary of seminary priests, have calculated that 471 priests were active in England between 1574 and 1603.Footnote 110

In 1598, Master William Love confessed that, after serving in a Spanish Armada, he had been hired to transport English priests and Jesuits. He was subsequently sent to the college in Saint-Omer, Flandres, where he encountered a brother of Robert Persons, S.J.Footnote 111 William Randall, described in an English report as an exceedingly skilled mariner and pilot, lived in Dunkirk with his Flemish wife. He was known as an active conveyor of priests and intelligence. The same English report stated that Randall was connected to prominent English Catholic clergy, including Cardinal William Allen (1532–1594) and Robert Persons.Footnote 112 Meanwhile, Joseph Creswell, S.J. (1556–1623) advocated for the business interests of an English conveyor. He petitioned the Spanish State Council to grant the exclusive right to an English conveyor from Saint-Malo, Francis Nayler, to transport metal, lead, and cloth from Spain to England.Footnote 113 For security reasons, Catholic sailors were considered the best option for such conveying operations. In May 1591, the priest William Warford (c. 1560–1608) sought a ship with a Catholic master in Protestant Amsterdam to travel from there to Newcastle.Footnote 114 Sanlucar de Barrameda became a key hub through which English priests secretly travelled to England. To support these clandestine journeys, the English clergy of the Sanlucar Chapel had access to the hospice of the Saint George Brotherhood, a colony of English merchants, which was frequented by English sailors—either released prisoners of war or those who had arrived in Spain on non-English ships.Footnote 115

English mariners could also provide expert advice. In the 1580s and 1590s, Robert Persons focused on the military liberation of England from Protestant heresy. In addition to his project to create a seminary of Catholic soldiers, he also sought to develop successful invasion plans for Philip II’s army. In March 1594, Persons received a document from pilots John Lambert (written as N. Lambert in the document) and John (Jo.) Jones, suggesting Milford, Hampshire, as the most suitable location for the Spanish forces to land in England.Footnote 116 This may not have been the first contact between Persons, S.J. and Lambert. In December 1590, on behalf of Philip II, official Fernando de Alvia tasked Persons and Colonel William Stanley with examining and interrogating a religious refugee and pilot, John Lambert, on navigation matters, with a specific focus on the English coast.Footnote 117

Like other English exiles in Spain, English sailors benefited from their connections to English priests for protection and support. In 1602, Persons claimed that thanks to his efforts, ‘no Englishman was put to death’ in Spain between 1588 and 1596. As Felipe Fernández-Armesto notes, ‘In Spain, the notion that Englishmen were irremediably tainted with heresy was reinforced by the foregone conclusions of the Inquisitions’, which, biased against anyone from a Protestant country, chastised all English people for any ignorance of the Catholic faith.Footnote 118 Regardless of how devout an English refugee might have been, he was never secure from suspicions of espionage.Footnote 119 In 1588, Spanish agent Antonio de Vega informed the government that the English Queen had sent many spies disguised as Catholic refugees to Spain and Italy.Footnote 120 In 1591, Persons wrote that the Spanish authorities ‘showed no confidence in any living person of our nation, both within and outside the kingdom.’Footnote 121

Points of tension

In 1593, Francis Englefield (c. 1522–1596), a King’s pensioner and an adviser on English affairs, compiled a report for the Spanish authorities regarding English and Irish officers in the fleet. This noted several competent English sea officers, while simultaneously warning of many suspicious Englishmen in Lisbon.Footnote 122 Both sides employed spies outside and within their territories, particularly during wartime. Englishmen typically accessed English intelligence through prisoners who were exchanged and returned to England. In September 1598, William Pitts, an English prisoner in A Coruña, was approached by several English sailors offering their services to the English government in exchange for a pardon or reward.Footnote 123 One of these was Andrew Facy, a former prisoner captured on the English coast who had become a pilot on one of the Spanish ships. Facy established contact with English intelligence through an English captain who had been taken prisoner and, at the time of their last meeting, was about to be sent to England as part of a prisoner exchange. In August 1598, Facy secretly sent a dispatch to the Lord Admiral, informing him of Spanish forces in A Coruña and requesting money to bribe Spanish officials.Footnote 124 There is no record of the Admiral’s response. The following month, Facy again asked Pitts to deliver a dispatch to the Lord Admiral or Earl of Essex. He reported on a 100-ton galleon and a 50-ton pinnace, which would enter the Channel with him as a pilot aboard.Footnote 125 Ultimately, he led these ships directly into English hands. During the voyage, Facy served as a pilot and interrogated English captives, performing the latter role so convincingly that they mistook him for a Spaniard.Footnote 126 From the source material remaining, one possible suggestion is that Englishmen like Facy, pressed from a Spanish prison, were probably more inclined to run away or betray the Spaniards than those who entered service voluntarily. The extant evidence suggests that the poor conditions and the Spanish authorities’ distrust of Englishmen were also factors. Not all sailors who contacted English agent Pitts in the Spanish prison were former captives; some may have feared persecution due to suspicions of their involvement in Richard Burley’s case. The zeal with which English individuals were pursued in Spain also raised the prospect that English Catholics might suffer imprisonment as well.Footnote 127

In 1593, Burley informed the Council of War that he had served the King in the waters of England and France for 20 years. He had fought aboard the galleon Rosario in the 1588 Armada and later in the squadron of Pedro de Zubiaur, based in Lisbon.Footnote 128 In 1595, under the orders of Don Diego Brochero, he led four galleys in a successful and risky raid on the Cornish coast.Footnote 129 During the 1580s, Burley, along with an Irishman, Patric Grant, spied for Spain, assessing which English and Irish merchants and sailors in Spain were good Catholics, suspicious, or heretics.Footnote 130 Despite his long and loyal service and achievements, in August 1598, he was imprisoned and tortured by the Spanish authorities.Footnote 131 This coincided with efforts to target and imprison all Englishmen suspected of collaborating with him in Seville, Ayamonte, and Sanlúcar de Barrameda.Footnote 132 Later, English Vice-Admiral Sir William Monson (c. 1568–1643) wrote that Robert Cecil (1563–1612) had framed Burley by planting a false letter among Spaniards.Footnote 133 This explanation is plausible, as English state papers contain no confirmation of Burley’s involvement in spying for England.

In general, Catholic seamen faced the same challenges as other Catholic immigrants. As Anne R. Throckmorton pointed out, exiles encountered poverty, instability, and the existential crisis triggered by displacement, which led to feelings of alienation, being outcast, and viewed as outsiders. Throckmorton illustrates this psychological crisis through the example of the well-known William Stanley, who experienced depression for several months while in Antwerp.Footnote 134 Exiles often abandoned family, friends, property, and material possessions, exchanging all of these for an insecure and isolated life among strangers who spoke an unfamiliar language. The likelihood of facing financial hardships, xenophobia, civil disabilities, and economic restrictions dramatically increased. They frequently experienced poverty, homesickness, and isolation, and were not entirely safe from arrest, especially if the host government decided to deport them back to their home country due to shifting international circumstances.Footnote 135

The cumbersome bureaucracy of the Spanish administration was one of the factors contributing to these issues. A 1592 English report noted that the Spanish authorities secretly sent agents to recruit English mariners and officers in Plymouth, Norfolk, and Newcastle, promising ‘large entertainment’ if they would accept the King’s service.Footnote 136 The Spaniards sought to hire English pilots with expertise on the English coastline, offering the promise of large wages and a prosperous life. However, the reality often fell short of these promises. In 1590, Captain Cripps wrote to the Council of War stating that English pilots and mariners at Ferrol were suffering greatly, having neither received their salaries nor been provided with provisions.Footnote 137 In 1591, a Spanish official reported that ‘most Irish, English, and Flemish officers of the Armada’ at Ferrol were in dire need of money to support themselves.Footnote 138 In 1593, four English officers in the Royal Armada petitioned the government urgently for payment due to their extreme need.Footnote 139 It should be noted, however, that Spanish sailors also faced issues with delayed payments and insufficient wages.Footnote 140 Perhaps the Irish, whom the Spaniards treated more favourably as a friendly nation, were occasionally better served than the English. In February 1595, two Englishmen, Francis Fowler and Edward Pickford, requested full payment of their salaries, similar to the payments received by the Irish entretenidos.Footnote 141 Overall, financial shortages were a common problem for all Catholic exiles.Footnote 142

Leaving Spanish service

Like other seafarers, Englishmen left service on Spanish ships in various ways, making it difficult to discern a common pattern. John Bonner resigned because of undermined health,Footnote 143 William Stucley died in service;Footnote 144 Richard Burley was arrested under the false accusation of espionage;Footnote 145 Robert Elliot departed for Scotland.Footnote 146 Due to incomplete evidence, it is impossible to determine the average length of service for English mariners. However, the table above suggests that the duration of their service was typical for this occupation, ranging from two to nine years, with Richard Burley as a rare exception, serving for twenty years.

Some Englishmen emigrated to the New World. Cases of Spanish and foreign sailors escaping ashore in the West Indies were frequent. The government stipulated severe punishments for this, but the chances of successfully finding escapees overseas were generally low.Footnote 147 In 1596, Doctor Burgos de Paz wrote that the English and other nationals sailed disguised as mariners on Spanish merchant ships to the West Indies and, upon reaching the destination, ran away from the ships inland, where ‘they are not asked from which land or nation they are.’ The assumption in this report that all runaways were spying for Protestant England reflects the wider distrust in Spain towards English nationals.Footnote 148 In the Spanish Americas, the Inquisition was less efficient at detecting suspicious foreigners because of the large distances, hardly accessible regions, and scarce and scattered populations.Footnote 149

English runaways who dispersed among locals in the Americas may have been culturally assimilated more rapidly than in Spain. Unlike in Spain, where there was a hospice for English merchants in Sanlúcar de Barrameda and relatively frequent sea communications with England, Englishmen had no such hubs in the Spanish Americas or Portuguese Brazil, the latter having been under Spanish control since 1580. The runaways settled among locals, like, for instance, four English seamen who jumped the English ship Minion in 1581.Footnote 150 Although rare, English Catholics continued to practice sailing in the waters of the West Indies. An account published by Richard Hakluyt reveals that in 1586, near La Plata, Cumberland’s men captured a Portuguese vessel with the English ‘master or pilot’ Abraham Cocke aboard.Footnote 151 Masters were usually responsible for religious services on Spanish ocean-going vessels.Footnote 152 Theoretically, Cocke could perform these religious duties.Footnote 153

Conclusions

In conclusion, English mariners entered Spanish service during the 1570s in the rebellious Netherlands, likely due to recruitment efforts led by Sir Thomas Copley. While conditions were favourable for recruiting zealous Catholics at this point, not all those who joined as sailors were religiously motivated; many were likely fortune-seekers. It appears that fewer English seamen entered Spanish service during the Anglo-Spanish War than had enlisted as privateers under Sir Thomas Copley in the 1570s. Paradoxically, although Copley professed loyalty to Queen Elizabeth, his pro-Spanish activities inflicted greater damage on Elizabethan policy in the waters of the Low Countries than those of many English exiles who openly opposed her rule.

The English maritime community in Spain was relatively small, with a more substantial presence in the home-based squadrons, particularly in the Lisbon Armada, than on West Indian ships. As demonstrated, this community formed for various reasons, including militant Catholicism, military fellowship, and family connections. Equally important were survival strategies, such as the release of mariners from prison in exchange for their conversion to Catholicism. These motives could be combined with other reasons for being in Spain, such as political ambitions or economic interests. Both English and Spanish spies were also present on the ships. To better understand the causes and motivations of this diverse community, further biographical studies of its members are needed. Such studies will offer a more detailed understanding of English mariners’ strategies for survival.

Suspicions of espionage and false Catholicism were part of everyday life in Spain. Alienation, isolation from broader society, and poverty—shared by all sailors, regardless of their religion, in both Spain and England—were also prevalent. In such conditions, connection to fellow countrymen, particularly English priests, must have been vital. This article has demonstrated that English sailors in Spain were linked to English priests, engaging in mutually beneficial collaborations, such as spiritual support or advocacy in political and economic matters, in exchange for expert advice or assistance with conveying operations. This collaboration between mariners and priests has yet to be fully explored, highlighting the need for further research and the discovery of new cases in archives.