Impact statement

Biological soil crusts, also known as biocrusts, are communities on the surface of desert soils that stabilize the ground, reduce erosion, trap dust and add carbon and nitrogen to otherwise infertile soils. In one of the hottest and driest regions on Earth, the Arabian Peninsula, these functions directly affect land degradation, air quality and the capacity of soils to support vegetation under extreme heat and aridity. However, this region has been largely ignored in global biocrust research. This article compiles what is currently known about which organisms form biocrusts, where they occur and how they function. Further, this work identifies the main pressures biocrusts face in the Arabian Peninsula, including grazing, off-road traffic, construction and rapid environmental change. This work outlines practical responses that can be deployed now. Some of these are protective, such as reducing disturbance so that intact crusts are not physically destroyed, and others are active restoration, which use locally adapted cyanobacteria and their partner microbes to seed new biocrusts on bare, eroding soil. This work also describes how shaded areas beneath solar farms can act as large-scale nurseries to grow biocrust material with minimal water use, directly linking renewable-energy infrastructure to land restoration. Biocrusts should be managed as core ecological infrastructure. Doing so offers a low-cost, climate-resilient way to stabilize degraded soils, keep nutrients in place for vegetation to recover, lock carbon into the ground and reduce dust that impacts human health. This has immediate relevance for drylands management and public health in the Arabian Peninsula and offers a pathway for other drylands that are moving toward similarly extreme conditions.

Introduction

Biological soil crusts (biocrusts) are communities of photoautotrophic (algae, lichens, cyanobacteria and bryophytes) and heterotrophic (bacteria, fungi, protozoa and nematodes) organisms that live within or in the uppermost millimeters of the soil (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Belnap, Büdel, Antoninka, Barger, Chaudhary, Darrouzet-Nardi, Eldridge, Faist, Ferrenberg, Havrilla, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa, Maestre, Reed, Rodriguez-Caballero, Tucker, Young, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou and Bowker2022). Biocrusts are estimated to cover around 12% of Earth’s land surface globally, and up to one-third of dryland areas (Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Belnap, Büdel, Crutzen, Andreae, Pöschl and Weber2018). In drylands, which constitute over 40% of the global land surface and are home to more than two billion people (Prăvălie, Reference Prăvălie2016), biocrusts function as ecosystem engineers, significantly contributing to soil stabilization, carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) fixation, nutrient cycling and influencing hydrology (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Bowker, Cantón, Castillo-Monroy, Cortina, Escolar, Escudero, Lázaro and Martínez2011; Pointing and Belnap, Reference Pointing and Belnap2012; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Reed, Travers, Bowker, Maestre, Ding, Havrilla, Rodriguez-Caballero, Barger, Weber, Antoninka, Belnap, Chaudhary, Faist, Ferrenberg, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa and Zhao2020; Sosa-Quintero et al., Reference Sosa-Quintero, Godínez-Alvarez, Camargo-Ricalde, Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, Huber-Sannwald, Jiménez-Aguilar, Maya-Delgado, Mendoza-Aguilar, Montaño, Pando-Moreno and Rivera-Aguilar2022; Garcia-Pichel, Reference Garcia-Pichel2023). The presence of biocrusts significantly affects soil fertility, vegetation dynamics and resilience to erosion and desertification, making them vital allies in the context of land degradation neutrality and climate change adaptation (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Mugnai, Rossi, Certini and De Philippis2018; Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Castro, Chamizo, Quintas-Soriano, Garcia-Llorente, Cantón and Weber2018). Despite this recognition, the global distribution of biocrust research remains heavily skewed toward regions such as North America, Europe, China and Australia (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Bowker, Cantón, Castillo-Monroy, Cortina, Escolar, Escudero, Lázaro and Martínez2011; Li et al., Reference Li, Hui, Tan, Zhao, Liu and Song2021; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Belnap, Büdel, Antoninka, Barger, Chaudhary, Darrouzet-Nardi, Eldridge, Faist, Ferrenberg, Havrilla, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa, Maestre, Reed, Rodriguez-Caballero, Tucker, Young, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou and Bowker2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ma, Yang, Ma, Zhang, Zhao and Chen2024; Rosentreter and Eldridge, Reference Rosentreter and Eldridge2025), while other major drylands, including the Arabian Peninsula, remain largely underrepresented in the biocrust.

The Arabian Peninsula, encompassing some of the hottest and driest environments on Earth – such as the Rub’ al Khali (“Empty Quarter”), vast gravel plains and coastal sabkhas (Vincent, Reference Vincent2008) – has been a “terra incognita” for biocrust ecology until very recently (e.g., Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010; Murgia et al., Reference Murgia, Fiamma, Barac, Deligios, Mazzarello, Paglietti, Cappuccinelli, al-Qahtani, Squartini, Rubino and al-Ahdal2019; Alotaibi et al., Reference Alotaibi, Sonbol, Alwakeel, Suliman, Fodah, Abu Jaffal, AlOthman and Mohammed2020). Early observations in this region were limited to anecdotal botanical surveys and incidental reports of cryptogamic diversity, including lichen records from southern Yemen, Kuwait and Oman (e.g., Müller, Reference Müller1893; Brown, Reference Brown1998; Pócs, Reference Pócs2009). These historical fragments hinted at a potentially rich but largely overlooked biocrust flora. Yet, systematic studies exploring biocrust composition, spatial distribution and ecological functions were absent until the past two decades (e.g., Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010; Murgia et al., Reference Murgia, Fiamma, Barac, Deligios, Mazzarello, Paglietti, Cappuccinelli, al-Qahtani, Squartini, Rubino and al-Ahdal2019; Alotaibi et al., Reference Alotaibi, Sonbol, Alwakeel, Suliman, Fodah, Abu Jaffal, AlOthman and Mohammed2020). Recent research conducted over this period has documented the presence of cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts, their roles in soil fertility and stability and the potential of indigenous microbial consortia for ecosystem restoration (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010, Reference Abed, Al-Sadi, Al-Shehi, Al-Hinai and Robinson2013; Murgia et al., Reference Murgia, Fiamma, Barac, Deligios, Mazzarello, Paglietti, Cappuccinelli, al-Qahtani, Squartini, Rubino and al-Ahdal2019; Alotaibi et al., Reference Alotaibi, Sonbol, Alwakeel, Suliman, Fodah, Abu Jaffal, AlOthman and Mohammed2020). However, these advances remain fragmented and geographically limited, underscoring the urgent need for a comprehensive synthesis of what is currently known about biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula.

In this review, we aim to consolidate the emerging body of research on biocrust diversity, composition and ecological roles in the Arabian Peninsula. Specifically, our objectives were to: first, integrate historical and recent records to resolve taxonomic composition and spatial distribution; second, assess how community structure and ecophysiological adaptations underpin key ecosystem functions; and finally, evaluate vulnerabilities to anthropogenic climate change and nonclimatic land-use pressures, alongside the potential of biocrust-based restoration to support sustainable land management and ecosystem resilience in this underexplored yet ecologically pivotal region. We provide an overview of the main taxonomic groups (lichens, bryophytes, cyanobacteria, algae and fungi) and explore their ecophysiological adaptations, distribution patterns and functional contributions across this area. Furthermore, we highlight knowledge gaps, identify future research directions and evaluate the potential of biocrust-based restoration approaches to support sustainable land management and ecosystem resilience in this underexplored yet ecologically pivotal region. The Arabian Peninsula represents some of the Earth’s most extreme environments and offers unique opportunities to understand biocrust resilience and adaptation under conditions of extreme aridity. This knowledge will be increasingly valuable in the current global context of climate change, with ongoing and forecasted widespread increases in atmospheric aridity (i.e., the degree of dryness of the atmosphere, which reflects the imbalance between atmospheric water demand [i.e., potential evapotranspiration] and water supply [i.e., precipitation]) across drylands worldwide (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Yu, Guan, Wang and Guo2016). By synthesizing available data and setting a forward-looking research agenda, this review aims to establish a scientific baseline that can foster a deeper understanding and more effective stewardship of biocrust communities across the Arabian Peninsula and other hyper-arid regions. We begin by providing an overview of how research attention has varied across different taxonomic groups and through time within the Arabian Peninsula, highlighting both well-studied and overlooked components of biocrust diversity. Next, we synthesize current knowledge on patterns of community composition and spatial distribution across the major biocrust constituents, with a particular emphasis on how these patterns are linked to key ecosystem functions such as soil stabilization, nutrient cycling, and water regulation. Building on this ecological foundation, we then assess the emerging impacts of anthropogenic climate change (i.e., shifts in temperature, atmospheric aridity and precipitation regimes) and nonclimatic land-use pressures (i.e., grazing, off-road traffic, urban expansion and pollution), which collectively threaten the persistence of biocrusts in the region, while also exploring management strategies to conserve or restore their ecological functions. Finally, we identify critical research gaps that remain specific to the Arabian Peninsula context and outline priorities for future investigations that could guide both scientific progress and evidence-based land management.

Bibliographic analysis of biocrust-forming organisms in the Arabian Peninsula

To analyze how research on biocrusts has evolved in the Arabian Peninsula, we searched Web of Science and Google Scholar using relevant keywords (“biological soil crust,” “biocrust,” “lichens,” “bryophytes,” “fungi,” “algae,” “cyanobacteria,” “Arabian Peninsula,” “Bahrein,” “Qatar,” “Yemen,” “Saudi Arabia,” “Oman,” “United Arab Emirates”). We evaluated the total number of publications per organism, per decade and the total number of references per year. Although the terms “biocrust” or “biological soil crust” have been rarely used until recent years, we included organisms fitting this classification, as defined by Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Belnap, Büdel, Antoninka, Barger, Chaudhary, Darrouzet-Nardi, Eldridge, Faist, Ferrenberg, Havrilla, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa, Maestre, Reed, Rodriguez-Caballero, Tucker, Young, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou and Bowker2022): “Biological soil crusts (biocrusts) result from an intimate association between soil particles and differing proportions of photoautotrophic (e.g. cyanobacteria, algae, lichens, bryophytes) and heterotrophic (e.g. bacteria, fungi, archaea) organisms, which live within, or immediately on top of, the uppermost millimetres of soil. Soil particles are aggregated through the presence and activity of these often extremotolerant biota that desiccate regularly, and the resultant living crust covers the surface of the ground as a coherent layer.” Accordingly, we only included terricolous organisms. Where available, we extracted the coordinates and data associated with the presence of biocrust or related organisms from those studies. A list of all the 161 references we identified is included in Figure S1 and Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

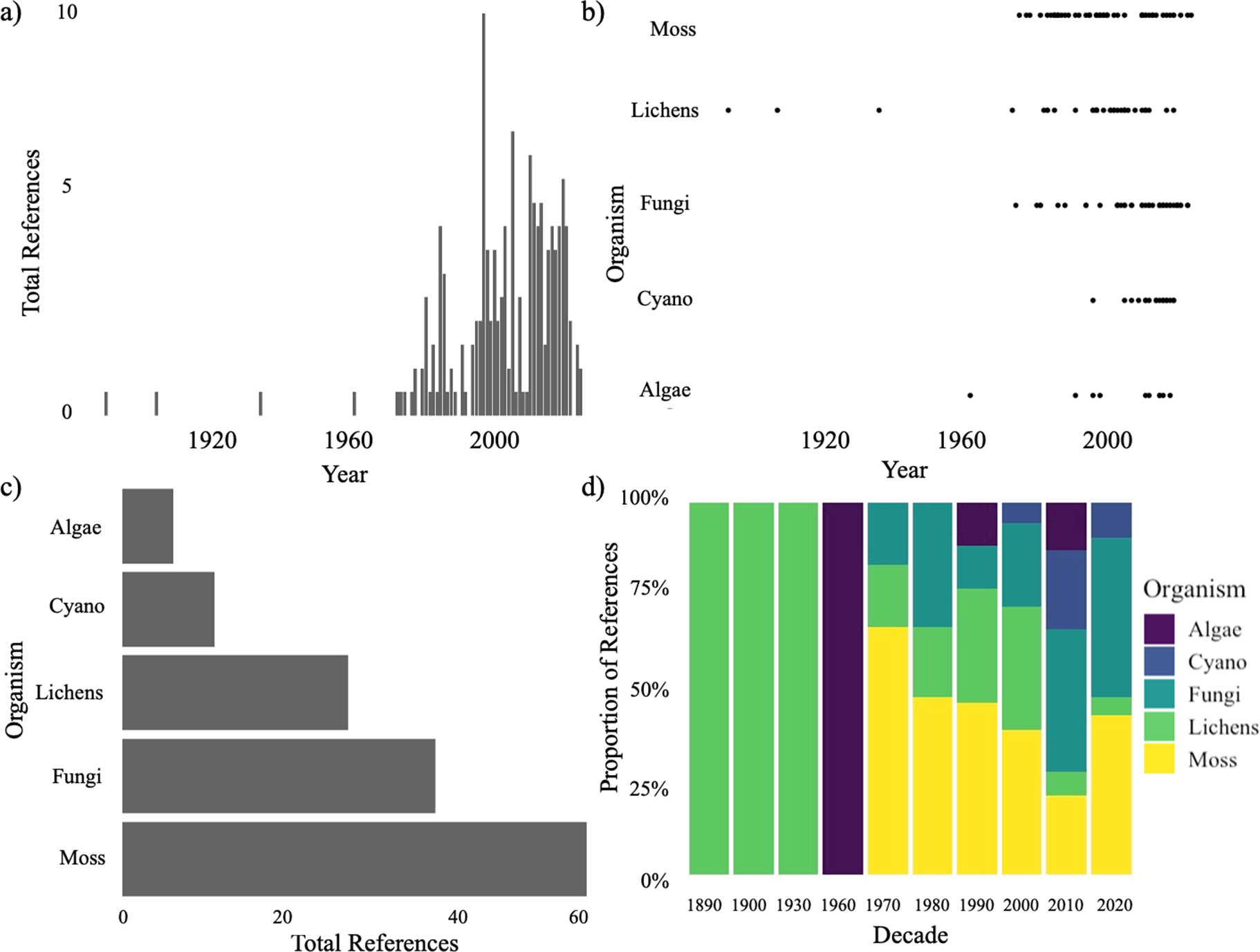

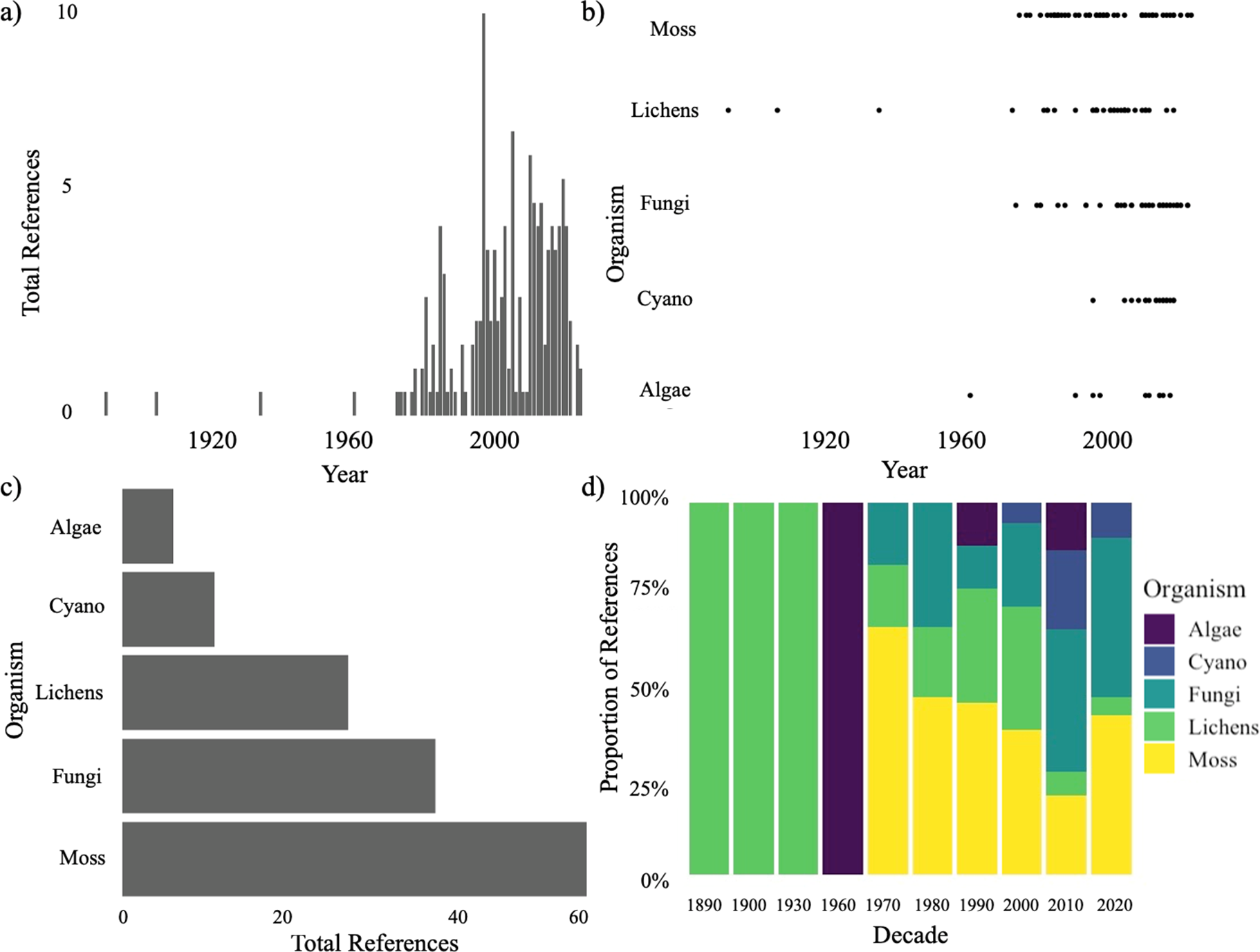

Our literature review highlighted clear temporal trends and taxonomic biases in the scientific literature on biocrust organisms in the Arabian Peninsula (Figure 1). Research has markedly increased since the 1970s, with the total number of references peaking in the early 2000s, followed by sustained but variable levels of research output in subsequent years (Figure 1a). However, before the 1970s, reference counts remained extremely low or absent, indicating limited historical research activity. Mosses emerge as the most frequently studied biocrust component overall, as shown by both the absolute reference counts (Figure 1c) and their dominance in earlier decades (Figure 1d). While lichens were the primary focus in early literature (pre-1960), mosses dominated from the 1970s through the 1990s. However, in more recent decades (2000s–2020s), the proportion of moss-focused studies has declined, while fungi and cyanobacteria have seen substantial increases in representation. This temporal trend suggests a broadening of research interest over time, with newer attention directed toward previously underrepresented groups such as fungi and cyanobacteria (Figure 1b). Collectively, these results suggest both historical and emerging trends in organismal focus, pointing to shifting priorities and growing taxonomic inclusivity in biocrust research.

Figure 1. Temporal patterns in the literature on biocrust-forming organisms in the Arabian Peninsula. (a) Annual total number of references. (b) Year of reference publication by organism group. (c) Cumulative reference count associated with each organism group across the entire dataset. (d) Decadal proportional distribution of references by organism.

Overall, our literature review highlights pronounced temporal and taxonomic biases, as well as uneven geographic coverage in existing research. These limitations underscore the need for a more comprehensive understanding of biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula. In the following section, we therefore examine current knowledge on their occurrence across the region, with particular attention to the dominant organisms shaping biocrust communities under different habitats and microclimatic conditions.

Biocrust community composition and distribution in the Arabian Peninsula

Recent surveys have provided the first detailed looks at biocrust communities in Oman (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Klempová, Gajdoš and Čertík2015; Maharachchikumbura et al., Reference Maharachchikumbura, Wanasinghe, Cheewangkoon and Al-Sadi2021). In coastal and central Oman, biocrusts appear across a range of soils, from alkaline loamy sands to silty loams, and climate settings (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). At lowland hyper-arid sites near the coast, biocrusts are usually thin, dark microbial films dominated by filamentous cyanobacteria (often appearing as a blackish soil patina). In contrast, at higher-elevation inland sites (e.g., Jabal Al-Akhdar ~2,000 m), both cyanobacteria-dominated and lichen-dominated biocrusts occur side by side, indicating that slightly cooler, moister conditions at altitude support the addition of lichens to the community (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019). Field observations confirm that cyanolichens (i.e., lichens with cyanobacterial partners) and chlorolichens (i.e., lichens with green algal partners) become more common in these upland biocrusts (Brown and Schultz, Reference Brown and Schultz2002). Lichen colonies appear together with dark cyanobacterial mats in certain montane sites of the Peninsula (e.g., Schultz, Reference Schultz1998; Abed et al., Reference Abed, Dobrestov, Al-Kharusi, Schramm, Jupp and Golubić2011). Together, these observations show a shift from simple cyanobacterial communities in exposed and harsher lowlands to more complex, lichen-rich communities at higher altitudes, where conditions are less extreme (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019). This pattern has also been documented in other drylands worldwide (e.g., Belnap, Reference Belnap2003; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Zhang and Wang2021). The next subsections discuss current knowledge of the major biocrust constituents across the Arabian Peninsula.

Cyanobacteria and algae

Cyanobacteria are the most consistently reported and compositionally dominant group in biocrusts across the Arabian Peninsula. Initial research explored algal communities in the saline soils of Al-Shiggah, Al-Qaseem, Saudi Arabia (Chantanachat, Reference Chantanachat1962; Arif, Reference Arif1992), identifying species adapted to high-salinity environments such as Nodularia spumigena. More recent investigations from inland desert wadis in Oman have documented hypersaline mats dominated by filamentous cyanobacteria, particularly Microcoleus, Oscillatoria and Phormidium, which collectively form dense microbial layers (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Klempová, Gajdoš and Čertík2015). In the southwestern regions of Saudi Arabia, including the Asir highlands, surveys have recorded occurrences of Nostoc, Anabaena and Chroococcus (Arif and El-Syed, Reference Arif and El-Syed1997). Cyanobacterial communities in Riyadh’s desert soils were also found to include widespread genera such as Nostoc and Oscillatoria (Al-Wathnani et al., Reference Al-Wathnani, Ara, Tahmaz and Bakir2012). In western Saudi Arabia, a more diverse assemblage was reported, with Lyngbya, Scytonema and Tolypothrix being among the 31 species identified (Al-Sodany et al., Reference Al-Sodany, Issa, Kahil and Ali2018). High-throughput sequencing analyses of arid soils from the regions of Abha, Hafar Al Batin and Muzahmiya, in Saudi Arabia, further confirmed the dominance of cyanobacteria across sites, with a strong representation from families such as Microcoleaceae and Nostocaceae (Khan and Khan, Reference Khan and Khan2020). Altogether, these studies indicate that, while filamentous cyanobacteria dominate in more extreme or saline habitats from the Arabian Peninsula, higher elevation and more vegetated zones support more diverse cyanobacterial assemblages (e.g., Schultz, Reference Schultz1998; Abed et al., Reference Abed, Dobrestov, Al-Kharusi, Schramm, Jupp and Golubić2011, Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019).

Fungi

Fungal and heterotrophic bacterial communities across the Arabian Peninsula exhibit substantial taxonomic and functional diversity, shaped by the region’s extreme aridity, high salinity and nutrient-poor soils (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al-Sadi, Al-Shehi, Al-Hinai and Robinson2013, Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019). In Saudi Arabia, early studies identified several specialized fungal groups, including halophilic, osmophilic and cellulose-decomposing taxa, with genera such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Cladosporium and Alternaria commonly reported from desert and saline soils (Abdel-Hafez, Reference Abdel-Hafez1981). In Bahrain and eastern Saudi Arabia, Fusarium species have received particular attention, with multiple species isolated from arid soils, reflecting regional fungal biodiversity (Mandeel et al., Reference Mandeel, Al-Laith and Mohsen1999; Mandeel, Reference Mandeel2006). Keratinophilic fungi, such as Chrysosporium and Microsporum, have been isolated from Bahraini soils, pointing to a distinct subset of fungal taxa specialized for decomposing keratin-rich substrates (Deshmukh et al., Reference Deshmukh, Mandeel and Verekar2008). In addition, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi have been recorded in various parts of Saudi Arabia, with Funneliformis mosseae frequently reported from both cultivated and natural saline habitats (Al-Qarawi et al., Reference Al-Qarawi, Mridha and Dhar2013). Molecular studies have revealed further diversity, with internal transcribed spacer (ITS) barcoding detecting a wide array of endophytic and rhizospheric fungi in association with native plants such as Rhazya stricta, including members of the Pleosporales, Hypocreales and Eurotiales (Baeshen et al., Reference Baeshen, Sabir, Zainy, Baeshen, Abo-Aba, Moussa and Ramadan2014). Recent metagenomic surveys have also identified oleaginous fungal genera, such as Mortierella, Mucor and Rhizopus, expanding the known fungal assemblages in Saudi desert soils (Moussa et al., Reference Moussa, Al-Zahrani, Almaghrabi, Abdelmoneim and Fuller2017; Yehia et al., Reference Yehia, Ali and Al-Zahrani2017). Studies from Kuwait have reported thermotolerant and halotolerant genera, including Emericella, Thermomyces and Aphanoascus, from sabkhas and sandy desert soils (Halwagy et al., Reference Halwagy, Moustafa and Kamel1982; Al-Musallam, Reference Al-Musallam1989).

Lichens

Early studies of lichens in the Arabian Peninsula date back to collections from mainland Yemen (Müller, Reference Müller1893), Socotra (Steiner, Reference Steiner1907) and Bahrain (Lamb, Reference Lamb1936). Subsequent studies by Mandeel and Aptroot (Reference Mandeel and Aptroot2004, Reference Mandeel and Aptroot2006) significantly expanded the lichen inventory of Bahrain, documenting both epiphytic and saxicolous taxa, including Ramalina, Lepraria and Dirinaria, which, although ecologically relevant, fall outside the scope of this review as they do not form soil surface biocrusts. In Saudi Arabia, research has primarily concentrated on montane and highland regions, where drought-tolerant lichens thrive under harsh arid conditions. Abu-Zinada and Hawksworth (Reference Abu-Zinada and Hawksworth1974) and Abu-zinada et al. (Reference Abu-zinada, Hawksworth and Bokhary1986) surveyed lichen diversity in areas around Taif, Abha and Al-Baha (Saudi Arabia), documenting the presence of species such as Parmelia, Usnea and Cladonia. Although Cladonia includes terricolous species forming biocrusts in drylands (e.g., Cladonia convoluta, Maestre, Reference Maestre2003), these cited surveys did not establish its occurrence on the soil surface. These areas, characterized by relatively higher elevation and seasonal moisture, support more diverse lichen communities compared to the surrounding lowlands. Lichenological work in Kuwait and Yemen revealed diverse cyanophilous taxa, such as Collema, Heppia and Peltula, adapted to extreme temperature fluctuations and low moisture availability (Schultz, Reference Schultz1998; Schultz et al., Reference Schultz, Brown and Büdel2000). Qatar-based studies have documented crustose and foliose lichens as integral components of biocrust and epiphytic communities, including Lecanora and Physcia, capable of withstanding high salinity and intense heat (Al-Thani and Al-Meri, Reference Al-Thani and Al-Meri2017; Al-Thani and Yasseen, Reference Al-Thani and Yasseen2018; Babikir and Kürschner, Reference Babikir and Kürschner1992;). On Socotra Island and in southern Yemen, taxonomic work has revealed island-specific endemics and new species, such as Heppia arenacea, Lempholemma polycarpum and Thelopsis paucispora, underscoring the region’s biogeographic uniqueness and the need for further exploration (Schultz, Reference Schultz2005; Breuss and Schultz, Reference Breuss and Schultz2007; Kukwa and Flakus, Reference Kukwa and Flakus2009). These findings collectively illustrate a rich, yet understudied, diversity of lichens across the Arabian Peninsula, shaped by microclimatic niches and extreme edaphic conditions.

Bryophytes

Early bryological surveys by Frey and Kürschner (Reference Frey and Kürschner1982, Reference Frey and Kürschner1984) provided the first systematic documentation of bryological diversity in Saudi Arabia, particularly from the Asir Mountains. These studies recorded arid-adapted species, such as Crossidium asirense, characterized by its compact growth form and xerophytic traits. Further exploration in central Saudi Arabia’s Jabal Tuwayq mountain range expanded the known bryoflora with new desert taxa exhibiting adaptations to high temperatures and episodic moisture availability (Frey and Kürschner, Reference Frey and Kürschner1987). Among these, Fissidens arabicus was described as a novel species, notable for its small, densely packed leaves and its growth in shaded rock crevices (Pursell and Kürschner, Reference Pursell and Kürschner1987), highlighting the morphological specializations of Arabian bryophytes.

Subsequent regional efforts have significantly expanded the bryophyte species inventory across the Peninsula, including surveys in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and Socotra. These inventories have documented taxa, such as Bryum radiculosum and various Barbula and Tortula species, many of which display desiccation tolerance and morphological adaptations to arid and semi-arid environments (Kürschner, Reference Kürschner2000; Kürschner and Sollman, Reference Kürschner and Sollman2004; Kürschner and Frey, Reference Kürschner and Frey2011; Kürschner and Ochyra, Reference Kürschner and Ochyra2014). The presence of these species across contrasting elevations, from montane zones to wadis and alluvial plains, reflects both the environmental heterogeneity of the region and the broad ecological amplitude of the bryophyte flora.

Comprehensive checklists and recent annotated inventories have further clarified species distributions across distinct habitat types, including sabkhas, rawdahs and escarpments (Hugonnot et al., Reference Hugonnot, Pépin and Freedman2025; Kürschner and Frey, Reference Kürschner and Frey2020; Taha, Reference Taha2019;). In Kuwait, bryophyte communities documented by El-Saadawi (Reference El-Saadawi1976, Reference El-Saadawi1978, 1979) included highly drought-resistant taxa, such as Didymodon spp. and Syntrichia spp., which persist under prolonged desiccation. In Yemen and Oman, surveys identified previously unrecorded bryophytes forming assemblages alongside vascular plants and cryptogamic biocrust elements, including Weissia, Funaria and Entosthodon (Kürschner and Ochyra, Reference Kürschner and Ochyra2004, Reference Kürschner and Ochyra2014). On Socotra, diverse bryophyte communities have been recorded in montane habitats, where species such as Riccia and Scopelophila contribute to the high endemism of the island flora (Kilian and Hubaishan, Reference Kilian and Hubaishan2006; Kürschner et al., Reference Kürschner, Al-Khwlani and Al-Gifri2015).

In general, taxonomic composition tracks environmental gradients, with cyanobacteria tending to dominate under harsher, more saline, or lowland conditions, while mixed communities of lichens, mosses and cyanobacteria are more common at higher elevations, cooler sites or more vegetated habitats. These shifts in community structure are expected to translate into distinct functional outcomes, as the capacity of biocrusts to stabilize soils, regulate water fluxes and mediate carbon and nitrogen cycling varies across taxa (Bowker et al., Reference Bowker, Mau, Maestre, Escolar and Castillo-Monroy2011; Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Reed, Travers, Bowker, Maestre, Ding, Havrilla, Rodriguez-Caballero, Barger, Weber, Antoninka, Belnap, Chaudhary, Faist, Ferrenberg, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa and Zhao2020; Concostrina-Zubiri et al., Reference Concostrina-Zubiri, Valencia, Ochoa, Gozalo, Mendoza and Maestre2021; Hoellrich et al., Reference Hoellrich, James, Bustos, Darrouzet-Nardi, Santiago and Pietrasiak2023). In the next section, we therefore explore how biocrust communities in the Arabian Peninsula contribute to these key ecosystem processes.

Ecological functions of biocrusts

Biocrusts deliver a range of vital ecosystem functions and services in the areas where they inhabit. Among them are dust suppression, erosion control, C sequestration, N fixation, the enhancement of soil fertility and hydrological regulation (Barger et al., Reference Barger, Weber, Garcia-Pichel, Zaady, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016; Durán et al., Reference Durán, Mora, Matus, Barra, Jofré, Kuzyakov and Merino2021; Gufwan et al., Reference Gufwan, Gufwan, Abdulraheem and Jaafar2025; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Sun, Jiang, Shang and Zheng2025). These functions and services are especially pertinent to the hyper-arid and arid landscapes of the Arabian Peninsula, where extreme temperatures, low and unpredictable rainfall with strong interannual variability and high wind activity make its soils particularly susceptible to degradation (Patlakas et al., Reference Patlakas, Stathopoulos, Kalogeri, Flocas and Kallos2019; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023). In this section, we explore key ecological functions and services provided by biocrusts that are essential for effective land management in this region.

Soil stabilization and erosion control

Perhaps the most prominent ecological role of biocrusts is physical soil stabilization (Mager and Thomas, Reference Mager and Thomas2011; Antoninka et al., Reference Antoninka, Faist, Rodriguez-Caballero, Young, Chaudhary, Condon and Pyke2020). Filamentous cyanobacteria, algae, fungi and lichens bind the topsoil into a cohesive layer that resists wind and water erosion, a vital function in sandy or silty deserts in the Arabian Peninsula and beyond (Figure 2). Growing evidence from the Arabian Peninsula indicates that biocrusts are important geomorphic agents in this region, reducing both wind erosion and sediment loss during rare rain events by stabilizing otherwise loose, sandy soils (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al-Sadi, Al-Shehi, Al-Hinai and Robinson2013, Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019). In the neighboring deserts of the Negev (Israel), cyanobacterial biocrusts stabilize dune sands and reduce sand movement (Veste et al., Reference Veste, Littmann, Breckle, Yair, Breckle, Veste and Wucherer2001), a process likely to occur in the Arabian Peninsula. Field studies in Oman found that biocrusts dominated by cyanobacterial genera such as Microcoleus, Nostoc and Scytonema on loamy sands enhance soil stability (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). In Qatar, Richer et al. (Reference Richer, Anchassi, El-Assaad, El-Matbouly, Ali, Makki and Metcalf2012) found that higher biocrust coverage correlated with lower soil erosion rates compared to bare soil, emphasizing their protective role. Galun and Garty (Reference Galun and Garty2001) noted that both cyanobacteria- and lichen-dominated biocrusts contribute to soil cohesion by binding particles and forming erosion-resistant layers, mitigating soil loss and preserving fertility and structure. Abed et al. (Reference Abed, Al-Sadi, Al-Shehi, Al-Hinai and Robinson2013) also reported that cyanobacteria- and lichen-dominated biocrusts in Oman improve soil aggregation, further supporting erosion control in arid environments. Furthermore, several studies have also highlighted the role of lichens and mosses in stabilizing soil surfaces. For example, the presence of drought-tolerant mosses, such as Syntrichia and Didymodon, recorded in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia (Taha, Reference Taha2019; Hugonnot et al., Reference Hugonnot, Pépin and Freedman2025) further supports their role in surface stabilization in the areas where these organisms are present.

Figure 2. Examples of cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts in (a) the Al Ula region (Saudi Arabia) and (b) central Saudi Arabia. Photographs by Corey Nelson.

Hydrological effects

While direct measurements of biocrust hydrological effects in the Arabian Peninsula are scarce, the presence of well-developed biocrusts is expected to modulate rainwater infiltration and runoff (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Reed, Travers, Bowker, Maestre, Ding, Havrilla, Rodriguez-Caballero, Barger, Weber, Antoninka, Belnap, Chaudhary, Faist, Ferrenberg, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa and Zhao2020). Depending on their composition and architecture, biocrusts can either increase or decrease soil infiltration of water (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Reed, Travers, Bowker, Maestre, Ding, Havrilla, Rodriguez-Caballero, Barger, Weber, Antoninka, Belnap, Chaudhary, Faist, Ferrenberg, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa and Zhao2020). Some biocrusts, especially those with rough surfaces (e.g., lichen- or moss-dominated), enhance surface roughness and can slow down runoff by creating micro-pores and channels in the crust, giving water more time to percolate. For example, cyanobacterial filaments can leave behind voids that can absorb water (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Mugnai, Rossi, Certini and De Philippis2018; Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Singh, Hashem, Abd Allah, Santoyo, Kumar and Gupta2023) and mosses can act like sponges (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Bowker, Maestre, Alonso, Mau, Papadopoulos and Escudero2010). Further, biocrusts’ fibrous biomass and polysaccharide secretions can improve soil’s water holding capacity and aggregate stability (Kakeh et al., Reference Kakeh, Gorji, Mohammadi, Asadi, Khormali, Sohrabi and Eldridge2021). In the Arabian Peninsula, where most rainfall is torrential but brief (Patlakas et al., Reference Patlakas, Stathopoulos, Flocas, Bartsotas and Kallos2021), biocrusts can help rainwater soak into the ground rather than immediately evaporating or pooling. During light rains, biocrusts protect the soil against raindrop impact and prevent surface sealing, while during intense storms, a crust layer can shed excess water as runoff, thereby directing water to discrete plant patches that harvest it, a process documented in the nearby Negev Desert (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Zaady and Shachak2002). Abed et al. (Reference Abed, Al-Sadi, Al-Shehi, Al-Hinai and Robinson2013) observed in Oman that cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts increased soil porosity and infiltration rates, while lichen-dominated crusts reduced infiltration due to hydrophobicity. Galun and Garty (Reference Galun and Garty2001) noted similar variability across Middle Eastern biocrusts, suggesting that regional differences in crust composition affect water dynamics.

Carbon fixation and soil organic matter

Biocrusts function as important C sinks at the soil surface, sequestering atmospheric CO₂ and enriching the soil with organic matter that can sustain soil food webs (Dou et al., Reference Dou, Xiao, Revillini and Delgado-Baquerizo2024, Reference Dou, Xiao, Wang and Kidron2022). The C fixed by biocrusts not only stays in their biomass, but is also released as polysaccharide slimes, litter (dead cells and lichens peeling off) or exudates, which enrich the topsoil (Garcia-Pichel, Reference Garcia-Pichel2023) and provide material for heterotrophic fungi and bacteria to decompose (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Thomas, Hoon and Sen2024). Galun and Garty (Reference Galun and Garty2001) described that Middle Eastern biocrusts, including those in the Arabian Peninsula and particularly those dominated by cyanobacteria, green algae and lichens, can maintain photosynthetic activity during moisture events, such as dew or fog. This metabolic flexibility enables episodic yet efficient C fixation, which accumulates over time and can therefore contribute meaningfully to C cycling in otherwise C-poor soils. Indeed, Abed et al. (Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019) observed that soil C content was increased under biocrusts compared to nearby noncrusted soils in Oman. These authors also found Actinobacteria to be abundant alongside primary producers in these biocrusts, indicating active C cycling within the biocrust community. Although studies in the Arabian Peninsula are largely missing in this aspect, biocrusts could also hold large potential for C sequestration (e.g., Kheirfam, Reference Kheirfam2020; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Tao, Peng, Wang and Wang2025), contributing to both environmental sustainability and economic development in the arid environments of the Peninsula, where organic C is naturally scarce (Plaza et al., Reference Plaza, Zaccone, Sawicka, Méndez, Tarquis, Gascó, Heuvelink, Schuur and Maestre2018; Schipper et al., Reference Schipper, Al Muraikhi, Alghasal, Saadaoui, Bounnit, Rasheed, Dalgamouni, Al Jabri, Wijffels and Barbosa2019).

Nitrogen fixation and nutrient cycling

N fixation by biocrust organisms, particularly cyanobacteria, provides a crucial source of N to dryland soils, supporting both the biocrust organisms and nearby vegetation (Dias et al., Reference Dias, Crous, Ochoa-Hueso, Manrique, Martins-Loução and Cruz2020). Heterocystous cyanobacteria, either free-living or within lichens (as in cyanolichens), continually enrich the soil by conversion of atmospheric N2 gas into nitrogenous compounds that are made available in the soil (Nawaz et al., Reference Nawaz, Joshi, Nelson, Saud, Abdelsalam, Abdelhamid, Jaremko, Rahman and Fahad2024). In Arabian biocrusts, Nostoc and Scytonema are prominent examples of N2-fixing cyanobacteria and, in Omani biocrusts dominated by these genera, significantly enriched soil N levels have been documented in association with high N fixation rates (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). Here, a high abundance of cyanobacterial sequences within the biocrust communities were associated with N-fixing genera and field samples showed significant nitrogenase activity (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). The N fixation capabilities of cyanobacteria have also been documented in other regions across the Arabian Peninsula, such as southwestern Saudi Arabia (Arif and El-Syed, Reference Arif and El-Syed1997; Al-Sodany et al., Reference Al-Sodany, Issa, Kahil and Ali2018) and close to Muscat, Oman (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). Cyanobacteria-dominated biocrust, through their metabolic byproducts, fertilize the soil with ammonium and amino acids, gradually building up soil fertility over long periods (Moreira-Grez et al., Reference Moreira-Grez, Tam, Cross, Yong, Kumaresan, Nevill, Farrell and Whiteley2019). Furthermore, when biocrusts are destroyed, studies record a decline in not only surface soil C but also N, demonstrating the importance of these organisms for nutrient accumulation (Kuske et al., Reference Kuske, Yeager, Johnson, Ticknor and Belnap2012). While well known for their role as soil fertilizers, biocrusts can also contribute to N losses. Abed et al. (Reference Abed, Lam, de Beer and Stief2013) reported elevated denitrification and nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions when cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts were moistened, rapidly denitrifying nitrate and producing N2O at rates an order of magnitude higher than non-crusted soil in Oman. Thus, biocrusts can act both as N sources (via fixation) and sinks (via denitrification), dynamically mediating N cycling in the Arabian Peninsula.

As discussed in this section, biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula operate as a tightly coupled system linking soil structure, hydrology, and biogeochemistry (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang and Belnap2016; Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019). Filamentous cyanobacteria, lichens, and mosses act as key structural agents by binding particles and forming soil aggregates, thereby reducing erosion from wind and water while retaining nutrient-rich fractions (e.g., Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023). Enhanced aggregation and increased surface roughness also moderate hydrological dynamics (Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Cantón, Chamizo, Afana and Solé-Benet2012; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Canton, Lazaro and Domingo2013), slowing runoff from short, intense storms and prolonging moisture residence after wetting events, which extends the window of biological activity (Rajeev et al., Reference Rajeev, Da Rocha, Klitgord, Luning, Fortney and Axen2013). These wet pulses activate photosynthesis and extracellular polysaccharide production (carbon inputs), as well as heterocystous N fixation (nitrogen inputs), reinforcing soil aggregation, fertility and conditions favorable for plant establishment, ultimately creating a positive soil–water–C–N feedback loop (Elbert et al., Reference Elbert, Weber, Burrows, Steinkamp, Büdel, Andreae and Pöschl2012; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang and Belnap2016). Conversely, disturbance disrupts this linkage: soil aggregation declines (Belnap, Reference Belnap2003), runoff and dust emissions increase (Belnap and Gillette, Reference Belnap and Gillette1998; Elbert et al., Reference Elbert, Weber, Burrows, Steinkamp, Büdel, Andreae and Pöschl2012), biological activity windows shrink (Rajeev et al., Reference Rajeev, Da Rocha, Klitgord, Luning, Fortney and Axen2013; Ferrenberg et al., Reference Ferrenberg, Reed and Belnap2015) and C and N fixation rates drop (Barger et al., Reference Barger, Weber, Garcia-Pichel, Zaady, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016; Belnap, Reference Belnap2003), often accompanied by post-wetting nutrient losses such as nitrate leaching or denitrification bursts (Homyak et al., Reference Homyak, Blankinship, Marchus, Lucero, Sickman and Schimel2016; Krichels et al., Reference Krichels, Jenerette, Shulman, Piper, Greene, Andrews, Botthoff, Sickman, Aronson and Homyak2023). Accordingly, minimizing disturbance and strategically aligning restoration interventions with natural moisture events can provide synergistic benefits for soil stabilization, water regulation and C–N cycling across the Peninsula (Antoninka et al., Reference Antoninka, Bowker, Reed and Doherty2015, Reference Antoninka, Faist, Rodriguez-Caballero, Young, Chaudhary, Condon and Pyke2020).

Environmental challenges and adaptations

Biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula endure some of the most extreme environmental conditions on the planet. The hyper-arid lands of the Peninsula are characterized by summer temperatures exceeding 45°C, intense solar irradiance and ultraviolet (UV) radiation, scarce and erratic rainfall (annual precipitation can be <50 mm in core desert areas) and, in many places, high soil salinity (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023). However, there are limits to the resilience of biocrust constituents (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Belnap, Büdel, Antoninka, Barger, Chaudhary, Darrouzet-Nardi, Eldridge, Faist, Ferrenberg, Havrilla, Huber-Sannwald, Malam Issa, Maestre, Reed, Rodriguez-Caballero, Tucker, Young, Zhang, Zhao, Zhou and Bowker2022), and increasing anthropogenic pressures as well as climate change are introducing new challenges. Here, we discuss how biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula respond to environmental stressors in a changing world.

Adaptation to extreme heat and desiccation

Many cyanobacteria and lichens can tolerate the environmental conditions typical of the Arabian Peninsula by suspending metabolism during dry spells and reactivating when water returns, as well as by an array of physiological strategies (e.g., Pointing and Belnap, Reference Pointing and Belnap2012; Pringault and Garcia-Pichel, Reference Pringault and Garcia-Pichel2004). For example, filamentous cyanobacteria, like Microcoleus, are highly motile and can respond to upcoming desiccation by descending the soil profile to escape lethal heat and UV exposure (Garcia-Pichel and Pringault, Reference Garcia-Pichel and Pringault2001). Further, they produce extracellular polysaccharides that retain moisture and slow drying (Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Cantón, Chamizo, Afana and Solé-Benet2012; Rajeev et al., Reference Rajeev, Da Rocha, Klitgord, Luning, Fortney and Axen2013; Kakeh et al., Reference Kakeh, Gorji, Mohammadi, Asadi, Khormali, Sohrabi and Eldridge2021). Some cyanobacterial species, such as Nostoc and Scytonema, synthesize scytonemin, a protective pigment, in response to UV radiation (Garcia-Pichel and Castenholz, Reference Garcia-Pichel and Castenholz1991; Mackelprang et al., Reference Mackelprang, Vaishampayan and Fisher2022). High concentrations of scytonemin in exposed biocrusts in Oman indicate that they are dominated by pigment-producing cyanobacteria able to resist intense UV radiation (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Al Kharusi, Schramm and Robinson2010). Likewise, some algae produce carotenoids that quench reactive oxygen species generated by high light and UV (Galun and Garty, Reference Galun and Garty2001). Fungal cell walls (including those of lichen mycobionts) contain melanin and other photoprotective compounds (Suthar et al., Reference Suthar, Dufossé and Singh2023). Moreover, in lichens, excess light is additionally dissipated by specific pigments in their algal partner (Beckett et al., Reference Beckett, Minibayeva, Solhaug and Roach2021). Heat tolerance is also critical, and enzymes and membranes of biocrusts are adapted to function at high temperatures. For example, some cyanobacteria alter the saturation of their membrane lipids to maintain fluidity at high temperatures (Galun and Garty, Reference Galun and Garty2001). However, as climate change pushes temperatures even higher and potentially prolongs droughts, these limits may be tested, making the hottest, driest edges of the region become too hostile even for biocrusts, contracting their range (Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Belnap, Büdel, Crutzen, Andreae, Pöschl and Weber2018; Baldauf et al., Reference Baldauf, Porada, Raggio, Maestre and Tietjen2021; McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023).

Vulnerability to physical disturbance

Biocrusts are highly susceptible to mechanical disturbances (Ferrenberg et al., Reference Ferrenberg, Reed and Belnap2015). In the Arabian Peninsula, common threats include trampling by livestock and humans, off-road vehicle use, construction, sand mining and oilfield activities, which crush or bury the crust, disrupting its structure and exposing underlying soil to erosion, as seen in Gulf countries (Al-Awadhi and Alkandary, Reference Al-Awadhi, Alkandary, Abd el-aal, Al-Enezi and Karam2024), Kuwait (Khalaf et al., Reference Khalaf, Al-Awadhi and Misak2013; Islam and Jacob, Reference Islam, Jacob, Suleiman and Shahid2023) and, specifically, Saudi Arabia (Assaeed et al., Reference Assaeed, Al-Rowaily, El-Bana, Abood, Dar and Hegazy2019). These physical disturbances reduce cyanobacterial abundance and N-fixing capacity, leading to decreased soil stability and fertility (Adelizzi et al., Reference Adelizzi, O’Brien, Hoellrich, Rudgers, Mann, Moreira Camara Fernandes, Darrouzet-Nardi and Stricker2022). Moreover, recovery of biocrusts in hyper-arid environments is exceedingly slow, with lichen and moss-dominated crusts predicted to take decades to centuries to fully recover (Kidron et al., Reference Kidron, Xiao and Benenson2020; Adelizzi et al., Reference Adelizzi, O’Brien, Hoellrich, Rudgers, Mann, Moreira Camara Fernandes, Darrouzet-Nardi and Stricker2022). Thus, in regions with a history of pastoral land use and increasing recreational activities, managing physical impacts on biocrusts is crucial. Beyond ecological impact, degraded soils are a source of fugitive dust with serious implications for human health (Etyemezian et al., Reference Etyemezian, Ahonen, Nikolic, Gillies, Kuhns, Gillette and Veranth2004; Griffin, Reference Griffin2007; Pointing and Belnap, Reference Pointing and Belnap2014; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Stanelle, Egerer, Cheng, Su, Cantón and Belnap2022). In North America, especially in the southwestern United States, loss of biocrusts due to off-road vehicles, grazing or urban expansion has been linked to increased airborne dust, which can carry harmful pathogens and pollutants (Etyemezian et al., Reference Etyemezian, Ahonen, Nikolic, Gillies, Kuhns, Gillette and Veranth2004) and is linked to respiratory issues, such as asthma, bronchitis and silicosis, particularly among vulnerable populations living near degraded areas (Griffin, Reference Griffin2007). Thus, protecting biocrusts not only preserves ecosystems but also contributes to public health by reducing dust emissions from arid landscapes (Pointing and Belnap, Reference Pointing and Belnap2014; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Stanelle, Egerer, Cheng, Su, Cantón and Belnap2022).

Climate change

The Arabian Peninsula is projected to experience rising temperatures, more frequent extreme heat waves and shifts in rainfall, from overall drying in some areas to slight winter-rain increases in others (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023). However, these precipitation increases are forecasted to coincide with rising temperatures, which will be particularly pronounced in the southwest of the Peninsula (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023). Warmer and drier conditions are expected to push biocrusts toward their physiological limits globally (Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Belnap, Büdel, Crutzen, Andreae, Pöschl and Weber2018). Experimental studies in global drylands have found that warming and reduced rainfall alter lichen metabolism and tissue chemistry, reducing their ability to regulate soil N cycling (Baldauf et al., Reference Baldauf, Porada, Raggio, Maestre and Tietjen2021; Concostrina-Zubiri et al., Reference Concostrina-Zubiri, Valencia, Ochoa, Gozalo, Mendoza and Maestre2021; Ferrenberg et al., Reference Ferrenberg, Reed and Belnap2015; Ladrón de Guevara et al., Reference Ladrón de Guevara, Lázaro, Quero, Ochoa, Gozalo, Berdugo, Uclés, Escolar and Maestre2014). Although, to our knowledge, no studies have yet examined the effects of climate change on biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula, insights from other dryland regions suggest that a warmer and drier climate in Arabian deserts could markedly alter community structure. In particular, increased aridity may reduce lichen cover (e.g., Baldauf et al., Reference Baldauf, Porada, Raggio, Maestre and Tietjen2021), since lichens are prone to faster desiccation and shortened periods of metabolic activity (e.g., Green et al., Reference Green, Pintado, Raggio and Sancho2018; Barták et al., Reference Barták, Hájek, Orekhova, Villagra, Marín, Palfner and Casanova-Katny2021) and drive shifts toward more stress-tolerant assemblages, characterized by greater dominance of cyanobacteria and reduced representation of mosses (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Coe, Sparks, Housman, Zelikova and Belnap2012; Finger-Higgens et al., Reference Finger-Higgens, Duniway, Fick, Geiger, Hoover, Pfennigwerth, Van Scoyoc and Belnap2022). Increased intensity of rainfall events is another predicted impact of climate change, where precipitation patterns are expected to shift from light beneficial rains to heavy downpours that can erode nascent crusts or leach away nutrients (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Román, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Moro2014; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Dai, Gao, Gan and Yi2021; Dou et al., Reference Dou, Xiao, Yao and Kidron2023). Further, these more intense events may bring stronger winds or storm events that physically disturb surfaces (Kidron et al., Reference Kidron, Ying, Starinsky and Herzberg2017; Kidron and Zohar, Reference Kidron and Zohar2014). While higher CO2 levels can enhance photosynthesis in cyanobacteria and lichens when they are active (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Maestre, Ochoa-Hueso, Kuske, Darrouzet-Nardi, Oliver, Darby, Sancho, Sinsabaugh and Belnap2016), potentially allowing them to use water more efficiently, any CO2 benefit will likely be negated by moisture stress and erosion if rains become rarer and more intense.

Because disturbance and ongoing climate trends can disrupt the stabilization–hydrology–biogeochemistry feedback outlined above, proactive management of biocrust communities becomes essential. In the next section, we evaluate potential strategies for the Arabian Peninsula, ranging from passive protection measures that safeguard existing biocrusts to active inoculation approaches designed to accelerate recovery under regional environmental conditions.

Restoration and management of biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula

As discussed in the previous section, the hyper-arid landscapes of the Arabian Peninsula face increasing pressures from climate change, intensified land use, urban expansion and overgrazing, leading to soil degradation, biodiversity loss and reduced ecosystem resilience. In this context, biocrusts emerge as a promising nature-based solution for restoring soil functions and enhancing land sustainability (Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Lucas-Borja, Pereira and Muñoz-Rojas2020; Gufwan et al., Reference Gufwan, Gufwan, Abdulraheem and Jaafar2025) and agricultural productivity (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Zhou, Ullah, Zhao, Wang, Su and Xiong2022; Gufwan et al., Reference Gufwan, Gufwan, Abdulraheem and Jaafar2025) in desert environments. Their proven roles in soil stabilization, C sequestration and hydrological control make them ideal candidates for supporting ecological restoration efforts in degraded drylands. However, biocrust restoration in the Arabian Peninsula is still in its early stages, and there is a lack of field-based applications and region-specific guidelines. This section examines emerging strategies for biocrust restoration and management, and identifies key challenges and opportunities for integrating biocrusts into dryland rehabilitation and conservation frameworks in the Arabian Peninsula.

Passive protection

The simplest biocrust conservation method is to prevent disturbance. In the Arabian Peninsula, this means managing land use to reduce activities that destroy biocrusts. Controlling off-road vehicle access in sensitive desert areas, creating designated trails and managing grazing pressure could allow existing biocrusts to remain intact and recover naturally. Incorporating biocrust awareness into land management plans, military training protocols and development projects is an important step for biocrust conservation (Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Castro, Chamizo, Quintas-Soriano, Garcia-Llorente, Cantón and Weber2018). Some Gulf countries, for instance, already restrict vehicular activity in dune ecosystems to combat desertification (Assaeed et al., Reference Assaeed, Al-Rowaily, El-Bana, Abood, Dar and Hegazy2019) and the beneficial effects of fencing for biocrusts have long been recognized across drylands worldwide (Figure 3) (Ayuso et al., Reference Ayuso, Oñatibia and Yahdjian2024; Karnieli and Tsoar, Reference Karnieli and Tsoar1995; Noy et al., Reference Noy, Ohana-Levi, Panov, Silver and Karnieli2021). Although natural recovery of biocrusts in hyper-arid parts of the Peninsula will be slow, given time and favorable climate conditions, disturbed crusts can regenerate from remaining fragments or propagules blown in from elsewhere (Hawkes and Flechtner, Reference Hawkes and Flechtner2002; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang and Belnap2016). Nonetheless, passive protection will be futile if the area is open to renewed disturbance.

Figure 3. Biocrusts along the Israel-Egypt border. The fenced, restricted-access zone on the Israeli side has allowed for passive long-term preservation of intact biocrust communities, in contrast to more heavily disturbed areas across the border (Noy et al., Reference Noy, Ohana-Levi, Panov, Silver and Karnieli2021).

Active restoration

Active restoration approaches inoculate soils with biocrust organisms, such as lichens, mosses and cyanobacteria, to promote biocrust formation on bare or degraded soils (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Mugnai, Rossi, Certini and De Philippis2018; Muñoz-Rojas et al., Reference Muñoz-Rojas, Román, Roncero-Ramos, Erickson, Merritt, Aguila-Carricondo and Cantón2018; Román et al., Reference Román, Roncero-Ramos, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Cantón2018; Giraldo-Silva et al., Reference Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Barger and Garcia-Pichel2019). There is a growing interest in using these organisms for land restoration in global drylands (e.g., Antoninka et al., Reference Antoninka, Faist, Rodriguez-Caballero, Young, Chaudhary, Condon and Pyke2020; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Adessi, Certini and De Philippis2020; Román et al., Reference Román, Chilton, Cantón and Muñoz-Rojas2020; Yadav et al., Reference Yadav, Singh, Hashem, Abd Allah, Santoyo, Kumar and Gupta2023; Jech et al., Reference Jech, Dohrenwend, Day, Barger, Antoninka, Bowker, Reed and Tucker2025), especially in regions where conventional approaches are impractical or cost-prohibitive. In particular, biocrust-forming cyanobacteria make ideal soil inoculants as they require less water and nutrients to establish than lichens and mosses and thus are better suited for the hyper-arid conditions of the Peninsula (e.g., Antoninka et al., Reference Antoninka, Faist, Rodriguez-Caballero, Young, Chaudhary, Condon and Pyke2020; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Mugnai, Rossi, Certini and De Philippis2018; Muñoz-Rojas et al., Reference Muñoz-Rojas, Román, Roncero-Ramos, Erickson, Merritt, Aguila-Carricondo and Cantón2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen and Hu2013; Nelson and Garcia-Pichel, Reference Nelson and Garcia-Pichel2021; Reed et al., Reference Reed, Coe, Sparks, Housman, Zelikova and Belnap2012). Two general methods have been developed for creating cyanobacterial biocrust inoculum: whole community cultivation and culture-based consortia approaches. Whole community cultivation uses remnant biocrust communities as seeds to grow the entire biocrust community (both phototrophic and heterotrophic components) under conditions that maintain the original microbial community composition but require an ample supply of remnant communities, which may not be present in hyper-arid areas (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Chen and Hu2013; Muñoz-Rojas et al., Reference Muñoz-Rojas, Román, Roncero-Ramos, Erickson, Merritt, Aguila-Carricondo and Cantón2018; Giraldo-Silva et al., Reference Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Penfold, Barger and Garcia-Pichel2020). The second approach, culture-based consortia, identifies and isolates key biocrust constituents from areas to be restored to create consortia of locally adapted cyanobacteria (Giraldo-Silva et al., Reference Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Barger and Garcia-Pichel2019). In areas of low biocrust coverage, this approach holds a large advantage as cyanobacterial consortia can be sourced from minimal material and cultivated indefinitely. In both these efforts, multiple studies have shown that compositional matching of cultivated to native communities, as well as conditioning inoculum to local conditions, can enhance establishment success and minimize ecological disruption (Román et al., Reference Román, Roncero-Ramos, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Cantón2018; Ayuso et al., Reference Ayuso, Giraldo-Silva, Barger and Garcia-Pichel2020; Giraldo-Silva et al., Reference Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Penfold, Barger and Garcia-Pichel2020). To our knowledge, no field-based biocrust inoculation trials have been reported from the Arabian Peninsula, but the region’s extensive degraded drylands and severe water limitation make it a high-potential test bed for locally adapted, cyanobacteria-led restoration.

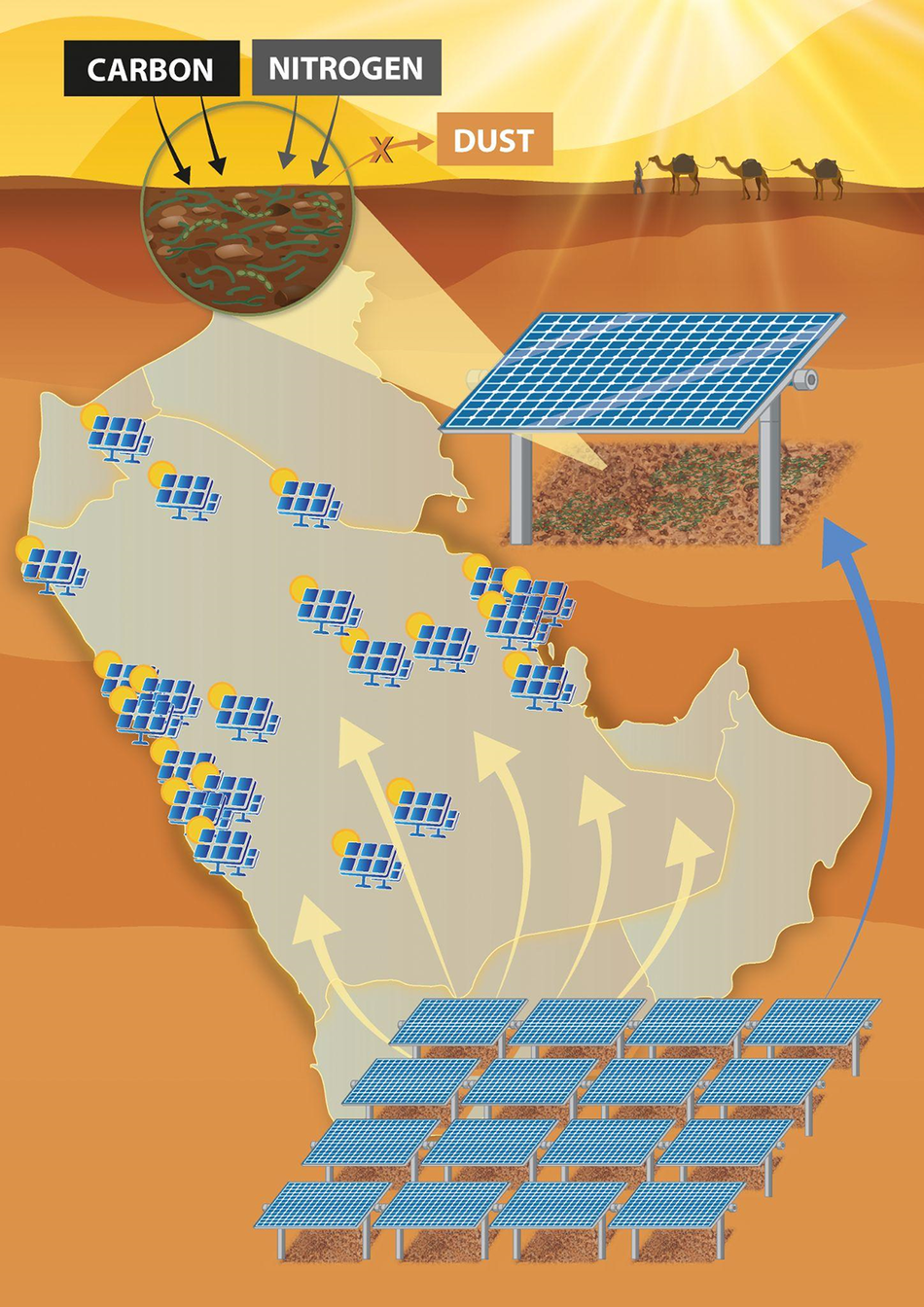

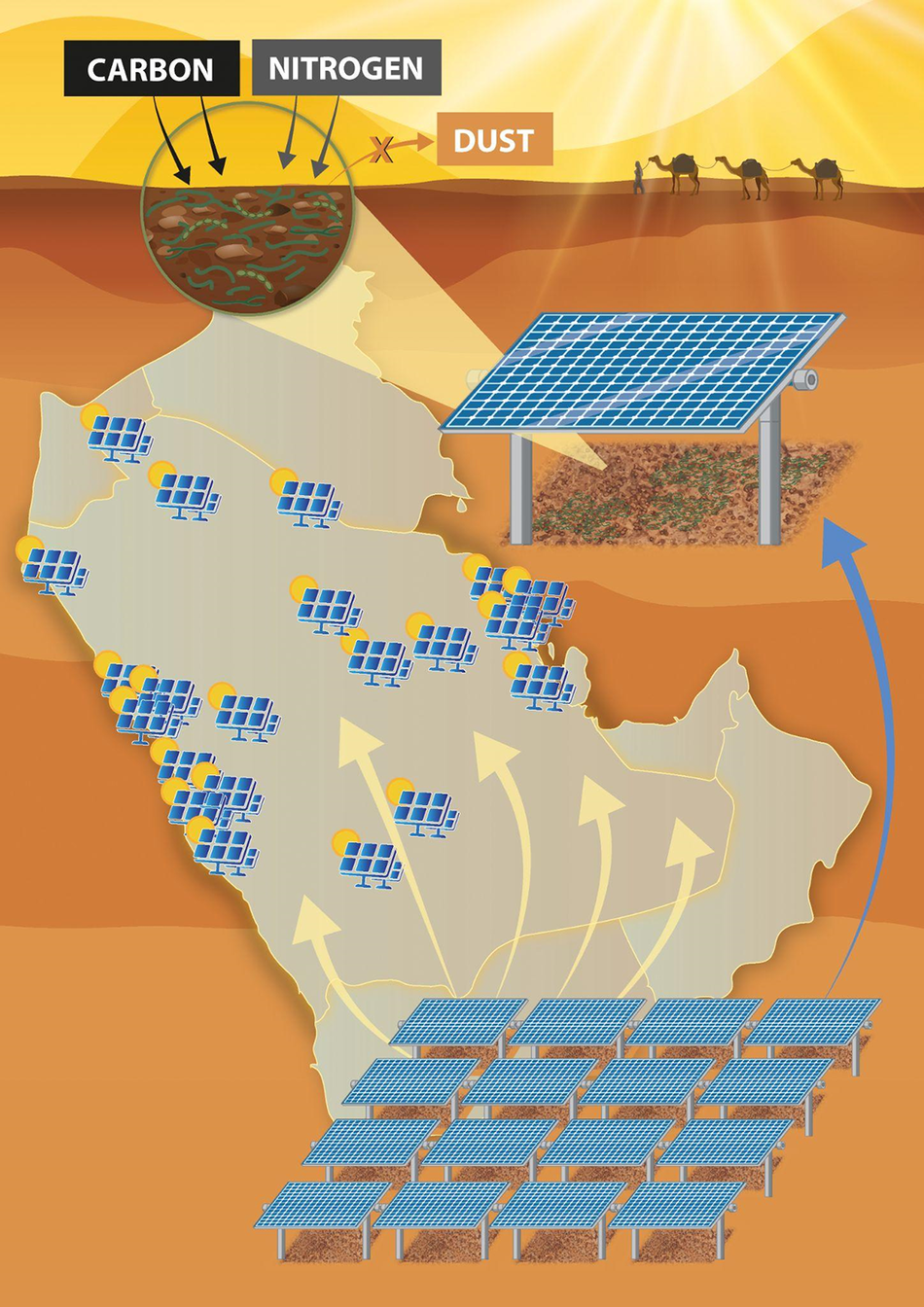

Despite advances in the active restoration of biocrusts, the scalability of these approaches remains a major challenge. Presently, most biocrust restoration approaches have infrastructure and manpower requirements that make restoring more than a few hundreds of square meters cost-prohibitive. However, a promising solution to this problem recently proposed demonstrated the potential dual use of solar power plants as biocrust nurseries (Heredia-Velásquez et al., Reference Heredia-Velásquez, Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Bethany, Kut, González-de-Salceda and Garcia-Pichel2023). In this study, the shaded environments beneath solar panels were found to promote the growth of biocrusts, and it was demonstrated that these areas could be used to continuously cultivate native biocrust communities at the hectare scale for transplantation to degraded soils. This innovative strategy not only leverages existing land uses for ecological and commercial benefit (e.g., C capture and dust mitigation) but also addresses key logistical barriers to large-scale biocrust production, such as land access, protection from disturbance and water management. This work provides a replicable model that could be highly relevant for the Arabian Peninsula, where expansive solar energy developments are underway (Hepbasli and Alsuhaibani, Reference Hepbasli and Alsuhaibani2011; Dasari et al., Reference Dasari, Desamsetti, Langodan, Attada, Kunchala, Viswanadhapalli, Knio and Hoteit2019). Integrating biocrust nurseries into the growing number of solar farms across the Arabian Peninsula could support local restoration goals while enhancing the multifunctionality of renewable energy infrastructure, making this approach especially appealing for desert nations seeking both sustainability and land rehabilitation outcomes (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Illustrating the dual-use strategy for large-scale biocrust cultivation beneath solar panel arrays in the Arabian Peninsula. The shaded microenvironments created under photovoltaic panels promote the establishment and growth of native biocrust communities, which, in turn, can enhance soil C and N levels while reducing dust emissions. These solar farms could serve as decentralized biocrust nurseries, enabling hectare-scale restoration efforts across the Arabian Peninsula. This approach has the potential to offer a scalable and sustainable model for integrating ecological restoration with solar energy infrastructure.

Knowledge gaps and future research directions

As presented throughout this work, research on biocrusts in the Arabian Peninsula is still in its infancy, and many questions about their ecology and biogeography in this region remain unanswered. Filling these knowledge gaps will not only advance ecological science in the region but also inform conservation and restoration efforts. In this section, we discuss key areas that future biocrust research in the Arabian Peninsula should pay particular attention to.

Biodiversity surveys across regions

In addition to earlier surveys (e.g., Abu-zinada et al., Reference Abu-zinada, Hawksworth and Bokhary1986; Mouchacca, Reference Mouchacca2005; Taha, Reference Taha2019), more recent work includes habitat-stratified biocrust community surveys in Oman (Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019), updated bryophyte floristics in Saudi Arabia (Hugonnot et al., Reference Hugonnot, Pépin and Freedman2025) and microbial diversity in Saudi sabkha and desert soils (Alotaibi et al., Reference Alotaibi, Sonbol, Alwakeel, Suliman, Fodah, Abu Jaffal, AlOthman and Mohammed2020). Despite these growing efforts, large extents of the Arabian Peninsula that could potentially host biocrusts, such as the gravel plains of Saudi Arabia, the Dhofar limestone plateau and the inland mountain ranges of Hijaz, remain largely unexplored and thus current knowledge of local biocrusts in these regions remains very limited. Therefore, comprehensive field surveys and sampling across different habitats in the region are needed. These should ideally combine traditional taxonomy with modern genomic techniques to capture the full genetic diversity of biocrust constituents. Given the high abundance of unclassified diversity (e.g., many unclassified fungal operational taxonomic units (OTUs) found in Oman [Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019]) and low coverage of microbial diversity in soils across the Peninsula, Arabian biocrusts will harbor undiscovered taxa. These efforts will uncover microbial biogeography patterns, refine our understanding of biocrust distribution and, thereby, improve predictions of how crusts may respond to climate change or other disturbances.

Ecophysiology and adaptation studies

The extreme conditions of the hyper-arid lands of the Peninsula make them ideal natural laboratories to understand how organisms function at physiological limits (Blanco-Sacristán et al., Reference Blanco-Sacristán, García, Johansen, Maestre, Duarte and McCabe2024). Future biocrust research in the Arabian Peninsula could examine, for example, the temperature and desiccation tolerance thresholds of locally dominant cyanobacteria and lichens, which have already been studied in other environments (e.g., Potts, Reference Potts1999; Gauslaa et al., Reference Gauslaa, Coxson and Solhaug2012). Lab and field experiments that simulate the diurnal cycles of heat and humidity can reveal the physiological strategies these organisms employ in the Peninsula, such as the activation of antioxidant systems (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang, Shu and Zhang2013) or the melanization of talli in fungi (Chowaniec et al., Reference Chowaniec, Latkowska and Skubała2023) to protect against high UV radiation. Further, in some areas of the Peninsula, such as Jiddat al Harasis in Oman and the Liwa Oasis region in the United Arab Emirates, heavy dewfall may sustain crusts in the absence of rain, as is the case in the Atacama Desert (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Baumann, Lehnert, Samolov, Achilles, Schermer, Wraase, Eckhardt, Bader, Leinweber, Karsten, Bendix and Büdel2020; Beysens, Reference Beysens2022). Measuring nighttime CO2 uptake to assess dew use by biocrusts could guide conservation and restoration by identifying areas favored by fog or dew. Such studies can also enhance understanding and help pinpoint species most at risk under worsening climate extremes.

Tailored restoration techniques to local conditions

A majority of biocrust restoration approaches have been developed for the drylands of North America and Asia (Rosentreter et al., Reference Rosentreter, Bowker and Belnap2007; Antoninka et al., Reference Antoninka, Faist, Rodriguez-Caballero, Young, Chaudhary, Condon and Pyke2020; Faist et al., Reference Faist, Tucker, Reed, Antoninka, Bowker, Barger, Dohrenwend, Day, Bellagamba, Belnap, Duniway, Fick, Giraldo-Silva, Nelson, Bethany, Velasco-Ayuso and Garcia-Pichel2020; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Zhao, Belnap, Zhang, Bu and Zhang2020; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Wang, Zhang, Pan and Jia2021), but region-specific trials are needed to test their applicability on the Arabian Peninsula. Given the high aridity of the Arabian Peninsula, these trials should focus on identifying the key native microbial biocrust species, like cyanobacteria, and test their capabilities for use as inoculum. Once comprehensive banks of local cyanobacteria and microalgae have been obtained, they could be used as inocula in field trials on degraded lands, like abandoned farms or overgrazed rangelands, to compare factors such as inoculum type (e.g., single vs. multispecies), use of mulch and timing of application.

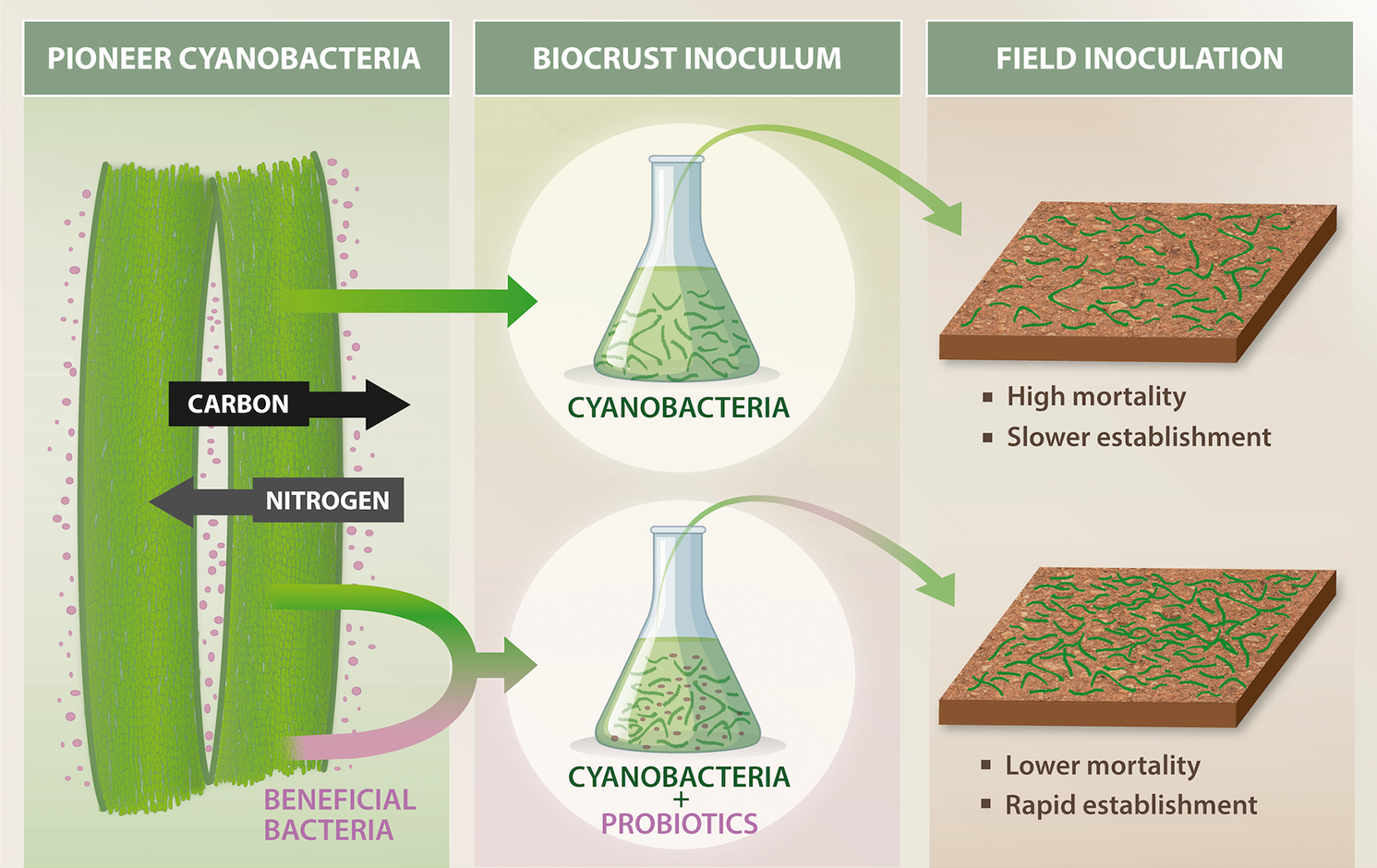

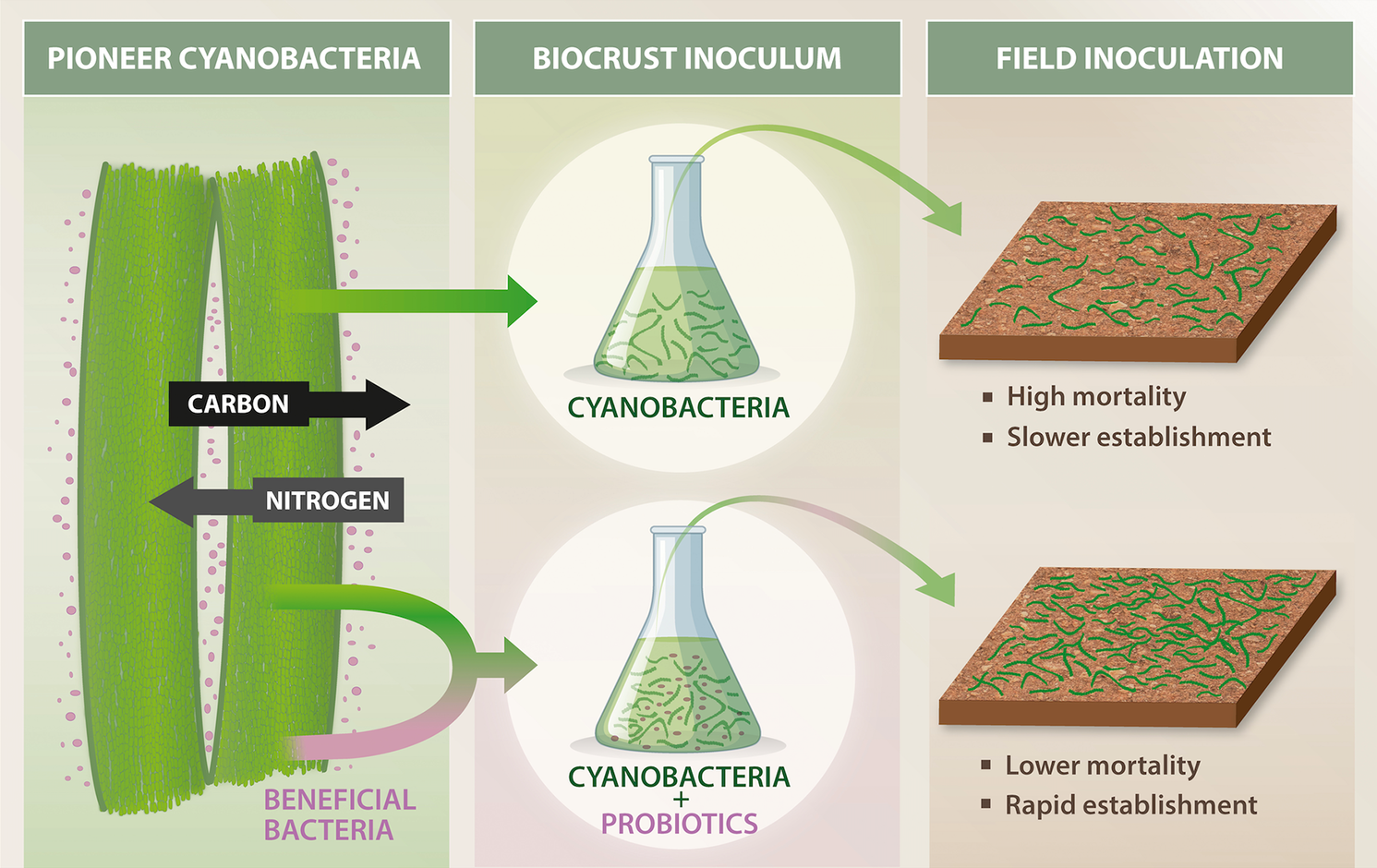

Evidence is growing that an understanding of biocrust microbial ecology is key to successful restoration efforts. Recently, it was discovered that cyanobacterial pioneers that form biocrusts maintain a N-fixing “cyanosphere” community (analogous to the rhizosphere), allowing the cyanobacteria to colonize N-poor bare soils (Couradeau et al., Reference Couradeau, Giraldo-Silva, De Martini and Garcia-Pichel2019; Nelson and Garcia-Pichel, Reference Nelson and Garcia-Pichel2021; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Giraldo-Silva, Thomas and Garcia-Pichel2022). The potential application of these microbial interactions was shown in a pioneer study that revealed the inclusion of “probiotic” cyanosphere bacteria not only leads to more rapid establishment of biocrust than inoculation without, but in some cases, inoculation with only “probiotics” was sufficient to regenerate biocrusts (Nelson and Garcia-Pichel, Reference Nelson and Garcia-Pichel2021; Figure 5). Understanding such synergisms could improve inoculum performance under harsh desert conditions, such as those on the Arabian Peninsula, and could significantly increase the feasibility of large-scale biocrust restoration in degraded drylands. Further investigation of these microbial interactions could lead to the development of consortia tailored to selectively enhance soil properties of interest, such as enhancing C and N cycling, dust capture or promoting growth of native vegetation.

Figure 5. Biocrust probiotics are beneficial heterotrophic bacteria that can enhance soil aggregation, nutrient cycling and community resilience when co-inoculated with pioneer cyanobacteria. These probiotics complement phototrophic functions, accelerating biocrust formation and stabilization in degraded dryland soils. Incorporating biocrust probiotics into restoration efforts can significantly improve the establishment and ecological function of biocrusts, especially under the extreme environmental conditions typical of the Arabian Peninsula.

Long-term studies

Long-term experimental plots are key to monitoring the effects of climate change, particularly if done across environmental gradients, both latitudinal and altitudinal (e.g., Fukami and Wardle, Reference Fukami and Wardle2005; Elmendorf et al., Reference Elmendorf, Henry, Hollister, Fosaa, Gould, Hermanutz, Hofgaard, Jónsdóttir, Jorgenson, Lévesque, Magnusson, Molau, Myers-Smith, Oberbauer, Rixen, Tweedie and Walker2015; Prager et al., Reference Prager, Classen, Sundqvist, Barrios-Garcia, Cameron, Chen, Chisholm, Crowther, Deslippe, Grigulis, He, Henning, Hovenden, Høye, Jing, Lavorel, McLaren, Metcalfe, Newman, Nielsen, Rixen, Read, Rewcastle, Rodriguez-Cabal, Wardle, Wipf and Sanders2022). Long-term monitoring of biocrust establishment and soil improvement can provide valuable insights for regional revegetation and dust control efforts (Kerem et al., Reference Kerem, Nejidat and Zaady2024; Gufwan et al., Reference Gufwan, Gufwan, Abdulraheem and Jaafar2025b). By maintaining multiyear monitoring of fixed sites with periodic surveys of biocrust cover and composition correlated with weather data, one might detect if warmer temperatures are leading to species shifts (Ladrón de Guevara et al., Reference Ladrón de Guevara, Gozalo, Raggio, Lafuente, Prieto and Maestre2018) or reduced productivity (Finger-Higgens et al., Reference Finger-Higgens, Duniway, Fick, Geiger, Hoover, Pfennigwerth, Van Scoyoc and Belnap2022). Because such long-term studies are rare in the region, even observational data (e.g., repeated photography of marked biocrust plots year after year (Swe et al., Reference Swe, Williams, Schmidt, Potgieter, Cowley, Mellor, Driscoll and Zhao2023; Qiu et al., Reference Qiu, Antoninka and Xiao2024) could be very valuable and provide early warning of climate impacts. Furthermore, collaboration with climate modelers to overlay biocrust distribution with projected climate envelopes might identify areas at risk of biocrust loss or, alternatively, new areas where biocrusts could expand if conditions become more favorable, as evaluated at a global scale (Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Belnap, Büdel, Crutzen, Andreae, Pöschl and Weber2018). For example, a slight increase in rain in parts of the Peninsula (McCabe et al., Reference McCabe, AlShalan, Hejazi, Beck, Maestre, Guirado and Peixoto2023) might allow biocrusts to form in places where they currently do not grow.

Bioprospecting and biotechnological potential

The extreme environments of the Arabian Peninsula are likely to harbor microbial communities with unique metabolic adaptations. These extremophilic microbes may possess novel enzymes, pigments and secondary metabolites with significant industrial applications, including pharmaceuticals, agriculture and bioenergy. For instance, desert biocrusts have been found to contain radiation-resistant bacteria, such as Deinococcus radiodurans and Rubrobacter radiotolerans, which exhibit remarkable resilience to ionizing radiation and could be sources of highly stable biomolecules (Mousa et al., Reference Mousa, Abu-Izneid and Salah-Tantawy2024). Furthermore, the robust growth, high photosynthetic efficiency and efficient nutrient uptake of cyanobacteria and algae from biocrusts also show potential for scalable biotechnological applications, particularly in biofuel production, aquaculture, nutraceuticals and wastewater treatment. Chantanachat (Reference Chantanachat1962) documented numerous algal species from arid soils in the Rubʾ al Khali (Empty Quarter, Saudi Arabia), introducing taxa such as Neochloris oleoabundans, notable for its high lipid content and prospective applications in biotechnology. Isolated green algae and cyanobacteria from Riyadh’s desert soils exhibited potent antibacterial properties (Al-Wathnani et al., Reference Al-Wathnani, Ara, Tahmaz and Bakir2012), while desert microalgae from Qatar showed exceptional resilience to extreme conditions, including successful cryopreservation (Saadaoui et al., Reference Saadaoui, Al Emadi, Bounnit, Schipper and Al Jabri2016). Metagenomic analyses of desert microbial communities have revealed a wealth of biosynthetic gene clusters involved in the production of bioactive compounds, including terpenoids, polyketides and nonribosomal peptides, underscoring their potential for biotechnological exploitation (Andreani-Gerard et al., Reference Andreani-Gerard, Cambiazo and González2024). Given the high proportion of unclassified microbial taxa already identified in preliminary studies carried out in the Arabian Peninsula (e.g., Abed et al., Reference Abed, Tamm, Hassenrück, Al-Rawahi, Rodríguez-Caballero, Fiedler, Maier and Weber2019), it is plausible that many novel taxa and potentially entirely new metabolic pathways remain to be discovered. Establishing a comprehensive strain library, coupled with genomic and metabolomic profiling, could unlock new avenues for the discovery of commercially valuable microbial products, positioning the region as a significant reservoir of biotechnological innovation.

Conclusion

Although often restricted to sheltered microsites and displaying patchy distribution in the Arabian Peninsula, biocrusts play an important role in stabilizing soils, regulating moisture dynamics at the soil–atmosphere interface and initiating nutrient cycling in some of the most extreme and nutrient-poor environments on Earth. Their localized yet persistent presence across the hyper-arid landscapes of this region underscores their ecological resilience and potential as keystone components in efforts to sustain and restore dryland ecosystems. Future research should prioritize comprehensive field surveys and high-resolution spatial mapping of biocrusts across the Arabian Peninsula, alongside applied studies on their use in restoring degraded soils, mitigating desertification and enhancing land and agricultural productivity under changing climate conditions. In particular, advancing restoration trials with regionally adapted inocula of biocrust-forming cyanobacteria and exploring practical frameworks for integrating biocrust nurseries into infrastructure developments, such as solar farms, should be central to the research agenda. Just as importantly, meaningful progress will depend on interdisciplinary collaboration among ecologists, microbiologists, land managers and policymakers to translate scientific knowledge into actionable, culturally relevant strategies for conservation and sustainable land management using biocrusts. By advancing our understanding of biocrusts, we can not only fill critical regional knowledge gaps about these often-overlooked organisms, but also contribute to the broader global agenda of building resilient ecosystems in a rapidly changing climate.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10007.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10007.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT (https://chat.openai.com/) during the preparation and review of this manuscript to improve the academic language and accuracy of the text. All AI-assisted text has been reviewed, verified and edited by the authors, taking full responsibility for the context of this work. The authors thank two anonymous reviewers and Sergio Ayuso, the handling editor of this work, for their comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of our work. J.B.-S. thanks Alexandre Soares Rosado and Tadd Truscott, for their genuine interest in biocrusts and for starting a promising conversation around these organisms in Saudi Arabia, where much is still to be discovered.

Author contribution

J.B.-S. conceived the idea and wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to the review and the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) Research Funding and Services (RFS) under Award No. RFS-2024-6206, funded by the KAUST Climate and Livability Initiative.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear editors,

I am writing to inquire as to the suitability of our manuscript “Biological Soil Crusts in the Arabian Peninsula: Ecological Functions, Current Knowledge and Research Gaps” for submission as a Review to Drylands. In this work, we present the first comprehensive synthesis of biological soil crust (biocrust) diversity, composition and ecological roles across the Arabian Peninsula, a hyper-arid region that has remained largely underrepresented in global biocrust research.

Our review highlights critical knowledge gaps in biocrust biodiversity mapping, ecophysiological adaptations and restoration strategies specific to the Peninsula’s unique landscapes. We outline a research agenda that emphasizes regionally tailored approaches, like leveraging solar‐farm infrastructure for biocrust nurseries, to foster large‐scale land rehabilitation and dust mitigation. Given the rapid expansion of development and the intensification of climate pressures in across the Arabian Peninsula, a thorough understanding of biocrust communities is urgently needed to integrate these microscopic pioneers into land management and greening initiatives. We believe this work will be of interest to your readers because it (1) synthesizes disparate data into a coherent framework for conservation and restoration in arid environments, (2) identifies locally adapted biocrust taxa and their potential applications and (3) proposes innovative, scalable strategies that link renewable energy infrastructure with ecological restoration. Moreover, by situating Arabian biocrusts within a broader dryland context, our review offers insights that are applicable to other hyper-arid regions worldwide.