8.1 Introduction

The manifesto is a call to arms in a battle that has long been fought: defining the purpose of education. In a world that seems so complex and confusing, how do we know what knowledge is relevant for children and young people? As Marenko (Reference Marenko2021, p. 166) said, ‘What does it take to imagine, design and inhabit spaces of experimentation, collaboration and reflection together? How can situations of this kind be crafted?’

In this chapter, Liam, a primary school teacher from Cambridge, presents two responses. The first response is his own experience from the University of Cambridge Primary School (UCPS). The second is from Oslo, Norway, where Aino is a doctoral student studying computational thinking and formative assessment, and Constantinos is professor of mathematics education, specialising in social, cultural and political dimensions of mathematics education; both have worked in schools. The manifesto is a challenging one. It requires different thinking about how we organise and make sense of knowledge(s) and how we craft an education experience that is future-making and dynamic.

8.2 Practitioner Wisdom from Cambridge, UK

My initial reaction to reading Pamela Burnard’s manifesto was to feel overwhelmed. I suspect I am not the only teacher who would feel this way.

The scale of the transformation described is staggering and, in some contexts, difficult to envisage. I read the manifesto again, and again. It brought me more questions than answers. When does cross-curricular, or ‘STEAM’ (science, technology, engineering, arts, mathematics), become transdisciplinary? Do we need to be transdisciplinary? Are silos important sometimes? I read the manifesto again. I thought a lot. I had the pleasure of meeting with Pam to discuss her ideas.

I am not suggesting that you re-read the manifesto umpteen times and seek out the author. What I am suggesting is that you try to keep an open mind when reading the case studies I share with you. Why? Because since reading this manifesto and hearing the term transdisciplinarity, I now – in an eerie Baader-Meinhof way – keep hearing it. I attended a talk by an assistant headteacher turned educational consultant and Ofsted (UK Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills) inspector – she referenced it. Then I heard about a local Cambridge primary school becoming part of the International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Programme – I did some research and found out that the programme is ‘an inquiry-based, transdisciplinary curriculum framework’, ‘guided by six transdisciplinary themes of global significance’ (International Baccalaureate, 2023).

Transdisciplinarity is not a far-flung idea impossible to create in our current education system, because it is already happening. When I can, I am trying to be transdisciplinary in my own classroom, and just down the road from where my own school is, more schools, and more teachers, are trying it too; more children are undergoing a transdisciplinary education than we might think.

To speak in the clearest terms possible, I see transdisciplinarity as a style of education in which the boundaries between subject-specific languages and themes are eroded (Burnard, Colucci-Gray and Cooke, Reference Burnard, Colucci-Gray and Cooke2022) and so ‘disciplines’ are explored in tandem, through inquiry-based learning, guided by teachers, but not in a purely instructional manner. Teachers may have a plan, but when the pupil leads them in another direction, they may choose to let this happen. It calls to mind the famous Reggio Emilia approach (Brunton and Thornton, Reference Brunton and Thornton2015), which also challenges the false dichotomy between the arts and sciences (Gardner, Reference Gardner, Edwards, Gandini and Forman1998). However, Pam is also developing new ideas, such as learning through forms of expression other than language. In my view, to begin with, we should not overthink transdisciplinarity, or worry about whether our practice is transdisciplinary enough – the important thing is to move from seeing education as comprising different, largely discrete subjects, to understanding those subjects as blended and interrelated, as they often are in everyday, adult life. If you are a primary teacher, you may well already be doing this in various different ways.

As Pam says, the future our children will inhabit as adults will be different from the world we currently inhabit, and this requires an evolving approach to education. A transdisciplinary education may better prepare our children for a world markedly changed by AI, climate change and shifting lifestyles, because these features of our lives are intersecting more and more. Many of the professions we now consider ordinary may soon be automated, but AI will also create new jobs that require ‘twenty-first-century skills’ (Holzer, Reference Holzer2022). School is absolutely about more than preparing children for the world of work, but stop to consider what you currently teach; while much of it may be crucial to children’s lives, much of it may no longer be relevant in its current form.

How can we enact large-scale change? Maybe we start small. If you teach maths and English by direct instruction in the morning, why not let children explore a project of their choosing in the afternoon? With the right stimulus and resources, children can engage in transdisciplinary exploration themselves – a child interested in science may attempt to give artistic representation to their (scientific) learning, for example. Can you integrate a transdisciplinary approach one morning a week? At my school, we replaced one afternoon science lesson – which we felt undervalued the science learning by squeezing it into the short post-lunch slot at the end of the day – for a weekly ‘STEM morning’, where science, maths, literacy and other subjects can convene. ‘STEM’ easily became ‘STEAM’ (to include art).

A transdisciplinary education ought to furnish learners the communicative, creative and analytical skills necessary to work alongside powerful AI systems or solve issues posed by climate change. At the same time, different things work in different settings and teachers must lead using their professional judgement.

Let me share with you some of the transdisciplinary learning I undertook with my children at the UCPS, based around enhancing some of these crucial ‘twenty-first-century skills’, namely creativity and innovation.

Title

Constellations: Transdisciplinary Learning across Scientific, Historical, Creative and Literary Boundaries

Liam Connolly

Context

The UCPS is a large, state-funded school established by the University. The open-plan design – the doorless classrooms are arranged around the ‘learning street’, a space that children and adults can use to learn independently or collaboratively – lends itself well to transdisciplinary learning, as does some of its resources; the school has vast outdoor spaces, including a forest area and outdoor classrooms. There is also the advantage of the link to the University and some of its academic departments, as you will see detailed in what follows.

What You Did

We had been learning about Earth and space for some time. We had already been talking about the night sky, the solar system and stars in a literary context through our work on the poetry collection Dark Sky Park by Philip Gross (Reference Gross2018), and this blended naturally with our science learning.

One week in April, we were privileged to visit the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, where Dr Matthew Bothwell and his colleagues gave us a tour of the universe and its history. The children were enthralled by the images and information, and their interest was piqued by the Northumberland Telescope, housed in a steel dome, which was once one of the largest refracting telescopes in the world, with a clock-driven equatorial mounting. ‘I never imagined a telescope would need to be so big!’ one of the children said, and they were even more surprised when Dr Bothwell told them there are many larger telescopes.

Back at school, we carried on a discussion about constellations that had begun at the institute. Using cardboard tubes and black paper pre-cut into squares, as well as pins, glue, cardboard boxes and paper, we made constellation tubes. To do this, I had printed some constellation patterns for children to cut out and stick to the black paper. Students then poked holes in the paper to make constellation patterns. Later, they used plain paper to create their own constellations. The children researched the names of the constellations and wrote them on the tubes, then swapped with each other to see the different constellations as they would be in the night sky. At the institute, they had been shown a very old book that featured drawings of the constellations and what they represented. The children were interested by the constellations that took the shape of animals. They were quickly able to spot parallels between the Latin names of the constellations and the modern English animal names, like Cygnus and cygnet, Delphinus and dolphin.

Later on, some children chose to create similar drawings, designing their own constellations and creatures to go with them, or redrawing historical ones, such as Ursa Major. They researched the stories behind the constellations and journalled their findings. A particular point of interest for many of the children, and one that was straightforward to capitalise on, was the fact that many of the constellations were based on animals. A very interesting point a child brought up at the institute was how some of the drawings of the animals differed to what they looked like in real life, and a staff member explained this was because the nineteenth-century illustrators had likely never seen the animal themselves and were drawing from someone else’s description. The children factored this into their work.

One child said that learning about constellations had made her think about the poem ‘Night Walker’ from Dark Sky Park and wrote her own poem about constellations that would sit alongside Gross’ collection. Later, we followed this up as a class, and more children wrote poems about what they had seen and learnt, mimicking Gross’ style, invoking techniques like enjambment to mirror the shape of the real constellations.

At the institute, the children had encountered real historical artefacts of a scientific nature, and they truly felt like astronomers. Coming back to school, I was able to engage them in a project that covered substantive knowledge from the science curriculum but invoked creative skills. The learning was not without challenges; the children’s interest in astronomy was not always equal. I encouraged those who were less interested in the constellation tube to find a different way of exploring the content, whether that was writing, carrying out their own research or something else. To ensure adequate rigour, it helps to have contingency ideas ready to prompt children who are unsure.

I wished to take the children somewhere to look through telescopes at the night sky and look for constellations themselves, though resources at the time did not allow for it. Fortunately, the community centre near the school sometimes holds such an event, and I encouraged the children to look out for it.

The trip to the institute was key to helping the children feel inspired and excited about constellations, which would not have happened had I introduced the subject by showing them pictures in the classroom; real-world experience is key for transdisciplinary learning and also a stepping stone for teachers to introduce a blend of disciplines. I would recommend beginning in this way – a trip, a visitor, an interesting object, a story, a problem (Russell, Wickson and Carew, Reference Russell, Wickson and Carew2008) – whatever resources you have, they can be contextualised in the real world. And, outside of school, it is quite rare that disciplines and skills remain siloed in the same way. Transdisciplinary learning has a power to break down boundaries and encourage new forms of creativity – many of the children were very proud of their achievements that day and were able to reflect on their successes in developing skills they did not previously consider themselves proficient in.

I am still learning about transdisciplinary practice, as we all are. I do not believe the example I just shared is a paragon of transdisciplinary practice, but it was one of the starting points for me, and a similar approach could be useful for you.

8.3 Practitioner Wisdom from Oslo, Norway

In an increasingly difficult time for state schools, resource scarcity may be one of your biggest challenges. Perhaps your resources align more fully with this second case study, from Aino Ukkonnen and Constantinos Xenofontos; you will notice it could not be more different from my own example, and yet it moves easily through subject disciplines, guided by real-world application, in a somewhat similar style.

Title

Context

In Nordic countries, like Finland and Norway, computational thinking (CT) and programming have been integrated into different school subjects (e.g. mathematics and science) for all school levels (from early years to upper secondary; ages six to eighteen). The lesson presented here provides a transdisciplinary platform for connecting computational sciences, mathematics and arts/crafts by making the computational practices visual and culturally embedded. This proposed lesson brings together ideas developed and applied in two different contexts, though with necessary adaptations to the Norwegian setting. Specifically, we draw on the work of Papageorgiou and Xenofontos (Reference Papageorgiou and Xenofontos2018) in Cyprus, who used ancient mosaics to elicit connections between geometric transformations, cultural awareness and the arts, and the work of Markkanen, Perttuli-Borobio and Juuti (Reference Markkanen, Perttuli-Borobio and Juuti2022) in Finland, in which pupils designed tote bags inspired by curricular goals for sustainable development. The lesson featured a selburose, a symbol of the Norwegian knitting culture (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 The selburose

What You Did

This proposed lesson is adaptable, depending on each classroom and the experiences of the children. It can be used for Grades 6–9 (approximately ages eleven to fifteen).

Key Concepts

Mathematical Key Concepts

Geometric patterns

Translation: sliding a figure in any direction

Reflection: flipping a figure over a line

Rotation: rotating a figure, a certain degree around a point

CT Key Concepts

Abstraction and patterns: recognising patterns in the structure of a selburose

Algorithms: designing the steps of instruction for drawing a selburose

Abstraction and efficiency: exploring how repetitions can be automated

Debugging: detecting and identifying errors in code

Tools

Pen and paper

Scratch on pad or computer (this project requires basic knowledge of Scratch)

Crafts: tote bag or knitting tools

Stage 1

Pupils first explore geometric patterns in their environment, and specifically, the selburose. This can be done by drawing with pen and paper and discussing the repetitions that occur in the pattern (Figure 8.2). Alternatively, or as an extension activity, pupils can create their own variations of the selburose by designing other patterns.

Figure 8.2 Geometric transformations

Stage 2

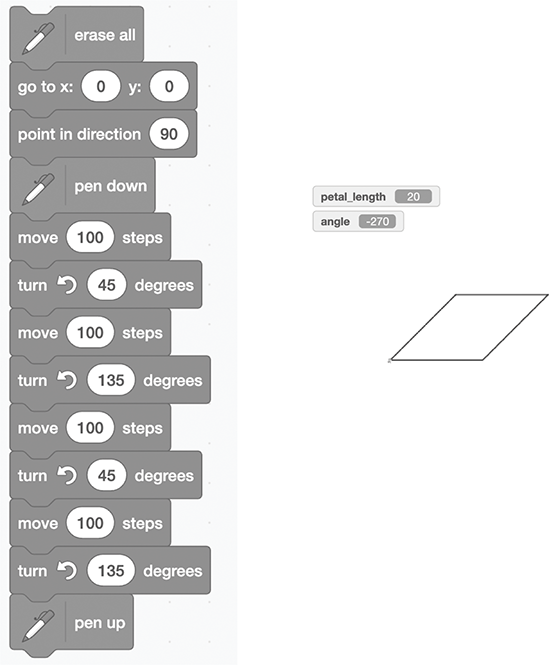

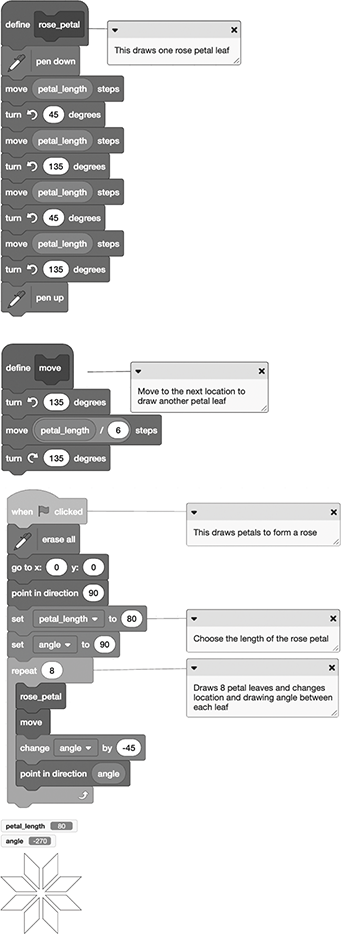

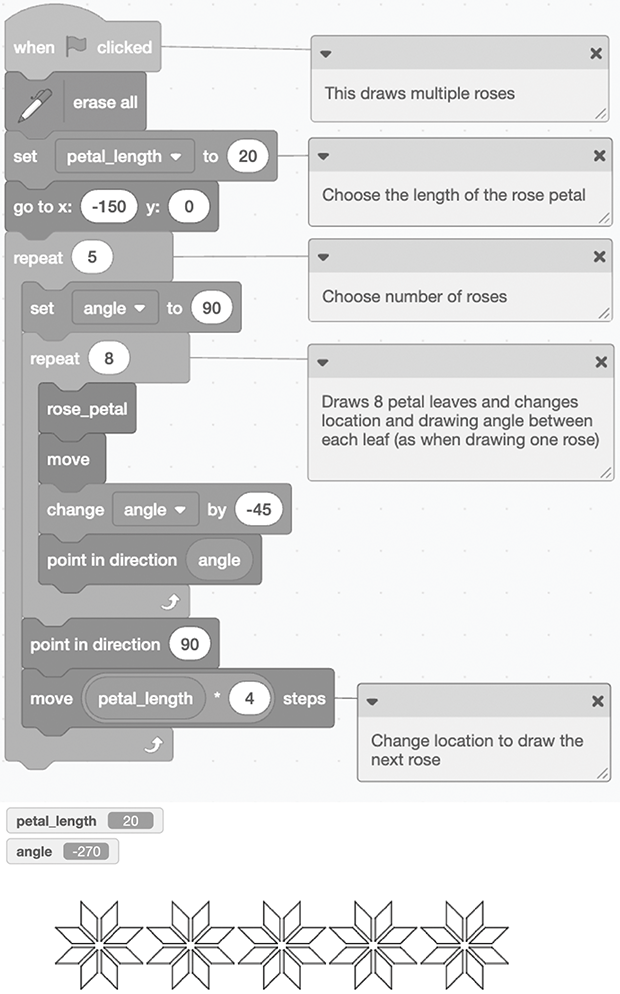

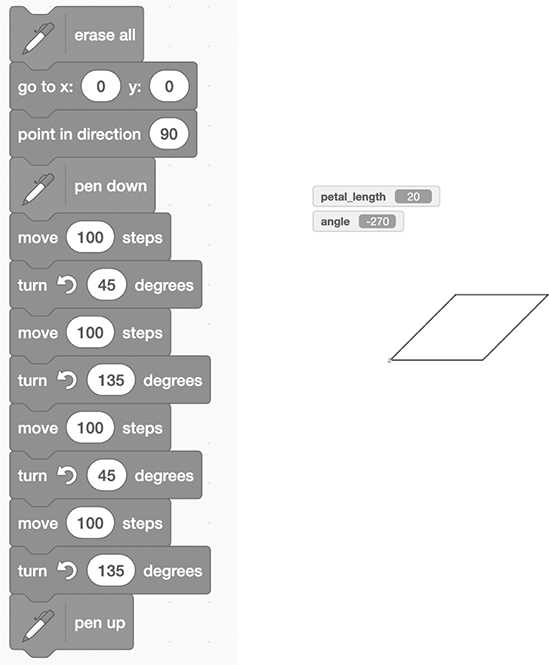

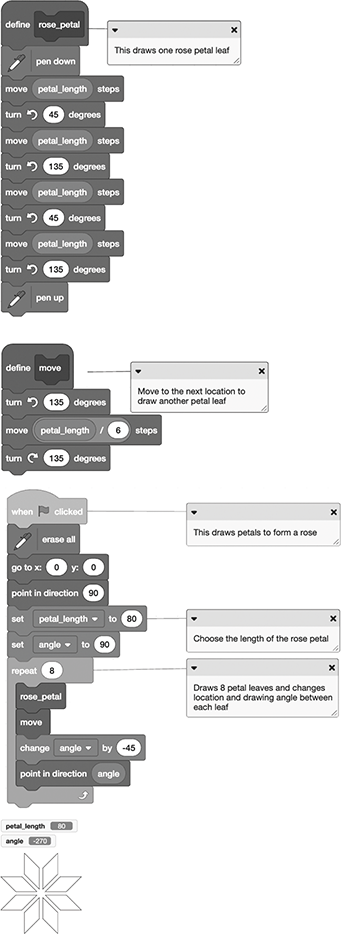

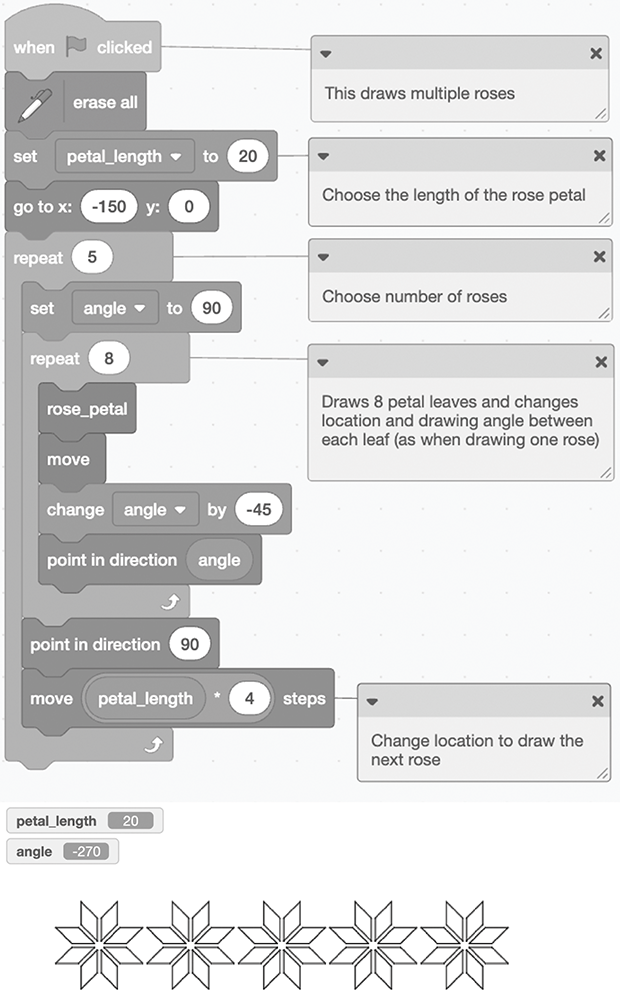

Mathematical and CT share similarities, such as problem solving and abstractions (Rich et al., Reference Rich2020; Shute, Sun and Asbell-Clarke, Reference Shute, Sun and Asbell-Clarke2017). The exploration of geometric patterns (either repeating or growing) can provide transdisciplinary learning opportunities for developing mathematical and programming skills simultaneously. As a subsequent activity, children can draw the selburose in Scratch, a free programming language and website widely used as an educational tool for children of ages eight to sixteen (see https://scratch.mit.edu).Footnote 1 They can start by drawing one petal leaf, and then use functions in Scratch to create the next leaf by rotating the initial one (see Figure 8.3). Later, they can use other functions to draw multiple roses (see Figure 8.4 and 8.5 variations).

Figure 8.3 One petal leaf and a Scratch code that produces the one leaf.

Figure 8.3Long description

The code sequence is represented by coloured pictorial blocks containing plain-text instructions in the following order: 1. Erase all, 2. Go to x: 0, y: 0, 3. Point in direction 90, 4. Pen down, 5. Move 100 steps, 6. Turn anticlockwise 45 degrees, 7. Move 100 steps, 8. Turn anticlockwise 135 degrees, 5. Move 100 steps, 6. Turn anticlockwise 45 degrees, 5. Move 100 steps, 6. Turn anticlockwise 135 degrees and pen up. The petal underscore length is 20 and angle is negative 270. The start position, step, and angle quantities appear to be inputted by the user. One petal leaf is shown on the right as the outcome of the steps followed.

Figure 8.4 The selburose drawn by having a function drawing each leaf.

Figure 8.4Long description

The code sequence to draw a single diamond leaf in Figure 4.3 is given. The sequence has been turned into a function by the addition of a code block header titled define rose petal, and the replacement of the hardcoded 100 steps with the variable petal length. An additional step at the end of the sequence instructs ‘pen up’. The sequence is labelled as drawing one rose petal leaf. A second drawing sequence function titled ‘define move’ is added below. It contains the following code blocks: 1. Turn anticlockwise 135 degrees, 2. Move petal length divided by six steps, 3. Turn clockwise 135 degrees. The sequence is labelled as moving to the next location to draw another petal leaf. Finally, a code block function allows the user to set the petal length and the angle along which the first line is drawn. The rest of the function then uses the previously-defined functions in a loop to draw the selburose. Below, the final selburose diagram output is shown.

Figure 8.5 Repeating the selburose five times.

Figure 8.5Long description

The code block function to define the drawing variables and draw the selburose now features an additional loop. This loop repeats the pattern a user-defined number of times by running the original instructions, then executing the following code blocks: 1. Point in direction 90, 2. Move petal length times four steps. A horizontal row of five selburoses is shown as the output.

In Scratch, visualisation is integral. Therefore, pupils get immediate feedback when running a piece of the program code. The instructions given to the computer (the algorithm) for drawing geometrical patterns can be explored; there are possibilities for refining it with abstraction, and debugging (finding errors in code) can be learned in the process. When drawing geometric figures in Scratch, the computer can be used to automate some of the repetitions. There are numerous ways to automate the process, and drawing the selburose in this program allows students to explore different forms of automation and abstraction. Hence pupils can explore CT and mathematics in conjunction.

Stage 3

Tote bags (Figure 8.6), usually made from a range of fabrics, such as canvas or cotton, are widely available and often considered a good alternative to plastic bags. In the next activity – one that can be linked to curricular goals about sustainable development, as well as arts/crafts – the designed pattern can be printed on tote bags with the use of a laser printer.

Figure 8.6 Tote bag

Reflecting Thoughts

This lesson can be extended to include ideas and concepts from different school subjects. For example pupils can find out about the history of the selburose, investigate how other cultures use similar or different patterns for crafts and be involved in writing activities. We believe such transdisciplinary approaches provide great opportunities for exploring issues of social justice by bringing discussions about cultural awareness and sustainability to the fore.

8.4 Conclusion

From these two case studies, you can see the reach and some of the potential of transdisciplinary practice.

That is not to say that becoming ‘a transdisciplinary teacher’ is easy, or even obligatory. Indeed, many practical barriers stand in the way; the datafication of our education system and the complex infrastructure of assessment and accountability that surrounds our classrooms make many people nervous of creative pedagogy. Transdisciplinarity does not always lend itself to recording and assessing in an Ofsted-friendly way (Allsup, Reference Allsup2016; Fautley, Reference Fautley2015; Regelski, Reference Regelski2016).

In the UK, schools are more challenged for resources than they have been for some time, and the lack of adult support (teaching assistants, learning coaches etc.) for teachers can undercut the potential for project-led learning. Balancing the needs of all learners is complicated, and if some children want to try something completely separate from the rest of the class, there is often the simple safeguarding issue that you do not have an adult to go off with them wherever they want to go.

To change quickly and on a grand scale would require a seismic effort (and a seismic cost). But we can be reflective and developmental in our own settings, to benefit our children, our schools and ourselves. For this, collaboration is key. Teachers have an enormous number of tasks in their existing remits, but if we work together, we can pool expertise and ideas. Professional learning communities are always a good place to start and are a key method of discussing and developing practice (Dimmock, Reference Dimmock2016; Hord, Reference Hord2009). Working together, we can learn to be agile and creative.

Creativity has vast benefits for children’s cognition, motivation, confidence and engagement (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2016; Kaufman and Sternberg, Reference Kaufman and Sternberg2010). And to foster creativity, it is imperative that we (educators and other adults) step back and allow learners to make choices (Cremin, Burnard and Craft, Reference Cremin, Burnard and Craft2006). Creativity is indisputably one of the ‘twenty-first-century skills’ (Holzer, Reference Holzer2022). Flexibility, adaptability and innovativeness will also be essential to the future lives of our learners (Zhao, Reference Zhao2012).

Transdisciplinarity is a way of engendering such skills and supporting our children to become well-rounded individuals who, as well as solving abstract problems in isolation, can merge what were once seen as subject-specific skills and languages and apply solutions to real-world issues. These are the skills that future generations will need: to find new ways of working, to circumvent climate change issues and to complement AI automation rather than being supplanted by it.

Over to You

These challenges are not challenges for the distant future; they are of the here and now. And education needs to adapt to face them. We must not be daunted, but excited. Upheaval – or disruption of the status quo – can be challenging. But it can also bring real positive change, of which educators can be a part. Read the case studies presented here again, and think about how you can start to make these ‘small’ changes in your classroom, because ‘big’ change is coming. As we end this practitioners’ response, we invite the reader to reflect on the following questions, drawing from their own wisdom and practices in their own classroom, school, social, cultural and educational contexts:

How can transdisciplinary thinking be developed in your school or educational context?

How does your curriculum design allow for opportunities to connect, reimagine and evolve the ways we present knowledges?

Where are the tensions and releases in curricula and pedagogy? Where do you find it confusing, difficult and frustrating? Are these the spaces for intercultural and transdisciplinary thinking?

In your context’s professional learning and development strategy, are there opportunities that challenge our assumptions about what learning, teaching, curricula, pedagogy, culture and spaces are? What do they mean for individuals and children, and what are the areas for discussion?

Are you and your team open-hearted and open-minded enough to reimagine what could be?

When and where do you ask, ‘What if?’