1. Introduction

This article discusses how peasant communities were affected by fire disasters related to tar production in northern Finland during the seventeenth century. It explains why the fires occurred, what was done to prevent them, how perpetrators were punished and what factors contributed to the resilience of peasant communities. This resilience was accomplished thanks to the level of reciprocity and communality embedded within the institutional framework of their communal ownership regime, which was created through collective action and shared goals, as well as with assistance from local authorities, using Swedish legislation, and from the institution of fire support (Swe. brandstod). In the Swedish Kingdom (of which Finland was a part until 1809), the importance of forest resources was particularly pronounced owing to the vast quantities of iron, copper, and tar that were produced and exported during the early modern period, which required enormous amounts of wood. Most forests were communally owned by the rural population in the form of commons (Swe. allmänningar) in various constellations.Footnote 1 During the seventeenth century, these commons not only were subjected to increased exploitation but also caught fire, with devastating consequences for individual households and for society at large. This article demonstrates how the benefits derived from their communal ownership regime were crucial for the survival of peasant households that had lived through a fire disaster.

Forests in the Swedish Kingdom were wide-ranging during the early modern period, and there were different kinds of commons and levels of management depending on the region. In central Sweden and in the mining district of Bergslagen, for example, there were several kinds of commons, whereas northern Finland had only two (Swe. byallmänning and sockenallmänning; Eng. village common and parish common). Whereas the peasants’ ancient use-rights to their forest commons were never questioned by state officials in northern Finland, many forest areas in the mining region were turned into rekognitionsskogar, which meant that use-rights were given to owners of mines and ironworks.Footnote 2 The reason for this development was the metal industry’s growing need of charcoal, and even though the production of charcoal was carried out by peasants in their commonly owned forests, crown officials and proponents of the metal industry exerted considerable influence over the management of forest commons in Bergslagen.Footnote 3 Nevertheless, recent research has shown that anthropogenic activities connected to charcoal production and other forest-related industries clearly impacted the fire regime of the region.Footnote 4

In Finland, the production of tar increased tremendously during the seventeenth century; up to 130,000 barrels of tar were exported each year during the 1680s.Footnote 5 The Finnish population’s relation to their natural environment ran deep. Traditions of using forest resources with the aid of fire remained common up until the late nineteenth century, Finland being one of the only countries in Europe that still burnt forest biomass on an extensive scale to clear land and fertilize the soil.Footnote 6 Nevertheless, as this article demonstrates, tar production resulted in a higher frequency of fires. Furthermore, previous dendrochronological research in the eastern region of Karelia (Finn. Karjala) has also shown that the number of wildfires peaked towards the end of the seventeenth century.Footnote 7 This shows a development where peasant communities were forced to deal with issues relating to wildfires on communal lands, fire prevention, socio-economic consequences, as well as strategies to increase the level of resilience within peasant communities.

Recent research has determined that regions characterized by communal ownership could be highly resilient in the face of exogenous shocks.Footnote 8 However, the role that communal ownership regimes played in terms of recurrent episodes of fire disasters has not yet been established. Nevertheless, since the 1960s, the frequency, intensity, duration and seasonality of wildfires in particular ecosystems have been studied. This is generally known as a ‘fire regime’, and the history of past fire regimes has since then been subject to much research within the ecological sciences.Footnote 9 In the Midwestern Tallgrass Prairie (MTP) in the United States, for example, early Europeans recorded how native populations during the 1670s engaged in large-scale landscape clearances with the use of fire, which was followed by a long line of written material, legislation and fire narratives that have been used to explain the development of the MTP fire regime.Footnote 10 However, fire regimes are not consistent; they often change. For example, in temperate Central European conifer forests today, fires are characterized by a high incidence, although with limited spread. Nevertheless, in the Białowieża forest in eastern Poland, for example, the historical fire regime was characterized by a high frequency up until the late eighteenth century with several major forest fires. After this period, no major fires have been detected, likely owing to changes in human forest-related activities.Footnote 11

Similar to charcoal production, tar production required an initial process of pyrolysis where wood was charred in tar pits; this gave the much-needed tar that was mainly used within the naval industry owing to its water-resistant properties. In the Nordic countries, research on wildfires has mainly been carried out within ecological research (fire history) and based on dendrochronological data with the aim of dating wildfires’ extent and occurrence.Footnote 12 For example, the county of Västmanland saw a high frequency of wildfires during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with a decline during the eighteenth century.Footnote 13 A similar development has been noted in southern Norway between 1600 and 1800.Footnote 14 However, these studies lack an important historical perspective since they do not explain how these events affected people’s lives and property, what role social relations and institutions played, or how legislation was used to preserve and protect forests and other land areas. There are, however, sporadic studies regarding how people have been prosecuted for having caused wildfires. Lars Kardell has, for example, shown how people could be sentenced to pay large fines, explaining how two peasants were sentenced to pay 100 silver thalers each in 1715 for having caused a wildfire near the Hällefors silver mine in Västmanland.Footnote 15 Another contribution comes from Sarah Cogos, Samuel Roturier and Lars Östlund, who have studied prescribed burning in northern Sweden during the early twentieth century,Footnote 16 something that the renowned fire historian Stephen Pyne has furthermore termed a mediation ‘between forestry’s fear of wildfire and its passion for fire exclusion’.Footnote 17

As mentioned earlier, scholars within disaster studies have increasingly addressed the resilience of peasant communities. The nature of different disasters could be many: flooding, sand drifts, storms, drought and famines, to name but a few.Footnote 18 The socio-economic consequences of such events could be dire and have given scholars good reason to investigate the level of resilience and vulnerability of past peasant societies; recent studies have shown how they were far from passive in reacting to exogenous crises.Footnote 19 In this context, the benefits derived from communal ownership regimes have been emphasized by many scholars during the last decades.Footnote 20 Common ownership regimes provided advantages of scale in realizing common efforts, facilitating monitoring of user groups and maintenance, and strengthening communality between users by the goals they shared.Footnote 21 Such ownership regimes could also be successful because of the practice of exclusivity in defining user groups, and through inclusivity achieving sustainable resource distribution.Footnote 22 Nevertheless, they were not exempted from periodical episodes of shock, crisis and disaster, induced by either natural phenomenon or anthropogenic activities.

It is not altogether easy to determine the level of resilience within a society. Nevertheless, much recent research on this topic is made possible owing to the hugely influential contributions made by scholars such as Elinor Ostrom and Tine De Moor.Footnote 23 One central reason why common-pool resources and common-pool institutions remained sustainable and resilient for many centuries is the increasing levels of communality, cooperation and stability that such resource regimes created.Footnote 24 This is something that Giulio Ongaro has emphasized contributed to the success of commons in early modern Italy.Footnote 25 Similarly, Maïka De Keyzer has explained how in the late medieval Campine region the management of common lands was facilitated through collective action that discouraged free-riding and countered over-exploitation.Footnote 26 In other circumstances, collective action of commoners was important in, for example, seventeenth-century England when the Crown endeavoured to enclose nearly 2,500 hectares in the forest of Dean; it was successfully reduced to just under one-fifth owing to protests from the local population, who argued that it infringed on their common rights.Footnote 27 Tim Soens has demonstrated the resilience of medieval communities in the North Sea area by analysing their strategies of coping with constantly high risks of flooding,Footnote 28 whilst Robert McC. Netting has shown that Swiss common-pool institutions have endured since the Middle Ages, right up to the present.Footnote 29 This particular development has been further investigated by Tobias Haller et al., who explain how this was made possible owing to the ability of commoners to balance market and state forces, which enabled them to create ‘the right mix of maintaining a resource base for the future but also creating a fair amount of profit and protecting it from degradation’.Footnote 30

To determine that a society was resilient, one must be clear on what the concept denotes. Since the 1970s, the concept has often been defined as the ‘buffer capacity’ of a society, or its ability to ‘absorb disturbance and re-organise while undergoing change so as to retain the same function, structure, identity and feedback’.Footnote 31 Some definitions also focus on the adaptive and transformative capacities of societies or socio-environmental regimes, and thus less on their ability of ‘bouncing back’.Footnote 32 Nevertheless, the level of vulnerability within past societies is important to consider, that is, how exposed communities and individuals were to disastrous events. It is important because, depending on the organization of a society, some groups or individuals can be made more vulnerable than others, which ultimately affects the resilience of the society in question.Footnote 33 For example, Heli Huhtamaa et al. have demonstrated how peasant-tenants under the Swedish Crown in early modern Ostrobothnia were worse off than freeholding peasants in the face of subsistence crises that struck the region at different times throughout the seventeenth century, which in part is explained by the more developed social networks and levels of wealth among freeholders.Footnote 34 Another example can be found in the south-western Netherlands, where property relations between commercial farmers and urban elites helped improve soil conditions after repeated events of flooding during the early modern period, something that local peasant communities were unable to do on their own.Footnote 35

Resilience and vulnerability are two concepts that are not mutually exclusive.Footnote 36 Nevertheless, according to De Keyzer and Soens, attempting to establish ‘an absolute level of resilience or vulnerability for all types of peasant societies or common pool institutions’ is futile since there is too much variation between societies and the potential risks and hazards they may encounter.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, Soens argues that a reasonable approach for establishing that a society was resilient is by ‘bringing the victims back in’ and investigating if past societies were able to ‘limit the exposure of people to suffering and disruption’.Footnote 38 In doing this, it is important to identify whether certain groups were worse off (physically or economically) whilst others benefitted as a consequence of a disaster. In other words, if a society or community was able to recover in an expedient manner, either through structural changes or by returning to a former structure of organization and management, then that society can be regarded as resilient. Conversely, if a society recovered but also produced vulnerable and exposed people, it cannot be classed as resilient.Footnote 39 However, one must also consider the relativeness of these concepts: the resilience and vulnerability of who and what? The reason is because the larger the unit, group or society (individual households, villages, parishes or whole regions), the more difficult saying something general about the resilience and vulnerability of the community becomes. In this article, this is determined by the ownership structure and the exploitation of natural resources that preceded events of wildfire, namely, the common-pool institutions (village and parish communities) and the tar production they practised.

How fire disasters affected the resilience of rural communities currently exists as a significant research gap in our understanding of history. In our own time, as global warming continues to be an escalating problem, vast areas of forests and land are burning every year, resulting in the destruction of ecological diversity and loss of property and human life. Surprisingly, this topic has not been sufficiently researched by historians, even though the use of forest resources and the management of fires in Europe have long histories. The area of investigation in this article is North Ostrobothnia, a place where forests were a central precondition for people’s lives and livelihoods owing to the vast amount of tar that was produced here during the seventeenth century. Furthermore, the source material from the region has enabled a thorough and scientifically coherent analysis that will give new insights into the field of disaster studies and commons research by explaining how peasant communities were able to overcome recurrent episodes of fire disasters by community, solidarity and reciprocity behaviours reinforced by the common-pool institutions they shared.

The structure of the article is as follows. In Section 2, the study area and analysed sources are presented in greater detail, together with climate reconstructions showing how climatological variations can affect the occurrence of fire disasters. Section 3 deals with the importance of communal action in tar production. Section 4 discusses how Swedish forest and fire prevention laws were passed and implemented in Sweden and North Ostrobothnia. In Section 5, the ways in which local communities and legal officials perceived different human causal factors leading to fire outbreaks is presented. Section 6 deals with how peasant communities were able to recover from fire disasters. The article is finally summarized with a conclusion where the results are discussed in Section 7.

2. Study area and sources

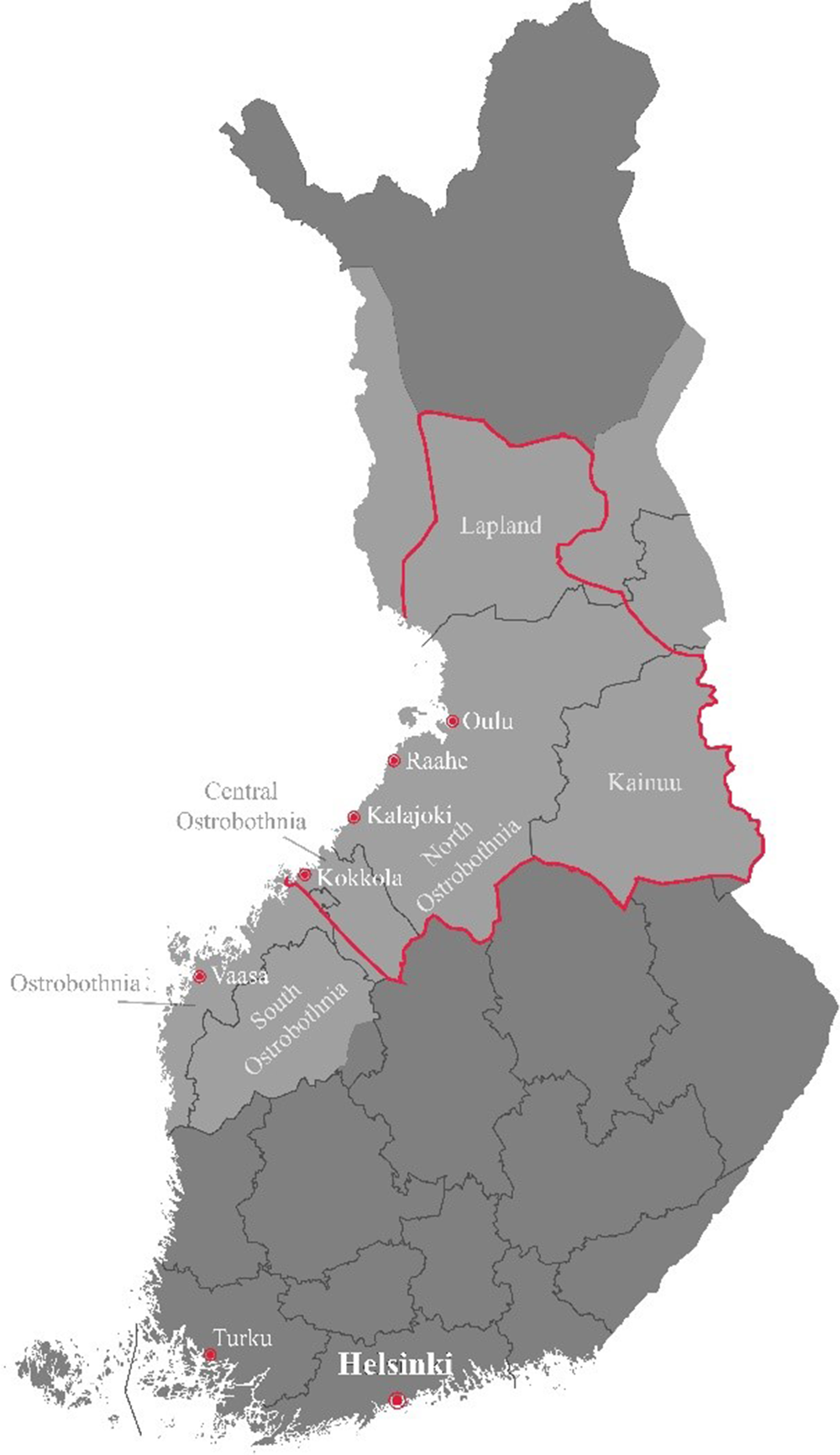

The region under investigation in this article is North Ostrobothnia, located in what is today Northern Finland (see Figure 1). Until 1809, it was an important part of the Swedish Kingdom, very much because of the tar production practised by peasant communities in the region.Footnote 40 It is here necessary to address the use of the English word ‘peasant’ in the context of the Swedish Kingdom. The definition of the concept ‘peasant’ (Swe. bonde) that is used in this article follows that of Olsson and Svensson, namely, ‘all non-gentry landholders managing farms that were subject to taxes and measured in mantal’ (mantal was an assessment of the taxable capacity of a farm or homestead).Footnote 41 The word ‘farmer’ is not used since a ‘bonde’ in the early modern Swedish Kingdom was a socially separated and politically represented social group and approximately 90 per cent of all land was managed by this group, whether as tenants of the nobility or the Crown, or as self-owners or freeholders.

Figure 1. Historical province of Ostrobothnia in Finland coloured in light grey and modern regions outlined in dark grey. The historical province of North Ostrobothnia and the region that is investigated encircled in red. Changes made: names of towns and the regions of modern Ostrobothnia added, the colour scheme changed.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Historical_province_of_Ostrobothnia,_Finland.svg.

The peasants of the region based their livelihood on field cultivation, which included a long-standing practice of slash-and-burn agriculture. This cultivation technique was widely practised in Finland throughout the early modern period, and it has been established that there was a clear correlation between the frequency of forest fires and the practice of slash-and-burn agriculture in western Finland.Footnote 42 However, even though the practice did not disappear completely, tar production came to dominate as the largest income-generating industry for peasant households in North Ostrobothnia during the seventeenth century, partly because of the region’s geographical suitability and vast forest landscapes and numerous waterways that were used as transport routes.Footnote 43 For this reason, the majority of fire disasters occurred as a consequence of tar production. Moreover, North Ostrobothnia is also an interesting region to investigate considering the polycentric and nested character of the peasant common-pool institutions, meaning that peasants organized governance and management activities at various levels.Footnote 44

The main source material that has been studied is local court records (Finn. Renevoidut tuomiokirjat). Each parish in the region had one local court, which usually assembled two or three times a year. These courts operated as a ‘low-cost arena for solving problems’, meaning that they were supposed to provide socially sustainable solutions to problems that occurred in the everyday lives of the rural population.Footnote 45 Furthermore, the courts had a profound attachment to local traditions since the jury (Swe. nämnd) consisted of people chosen from the local community to ensure that its interests were catered for. As such, the legitimacy of the courts was largely based on the active participation of the peasant community, as ‘the jury represented the community and its knowledge of local people and circumstances’.Footnote 46 The local courts were where people went to solve a wide range of different issues in their daily lives. Whilst some matters related to the management of forest commons could be solved in an operational setting, more serious problems had to be treated in a collective-choice situation where all stakeholders had the opportunity to have their say, which took place at the local courts.Footnote 47 Therefore, the local courts were the centre for collective decision-making when matters regarding, for example, communal ownership had to be discussed in a formal setting. However, a court was not only a place used to resolve conflicts. It was also here that people went to discuss and solve issues related to outbreaks of fire and to collectively decide on matters that increased the level of resilience in their communities.

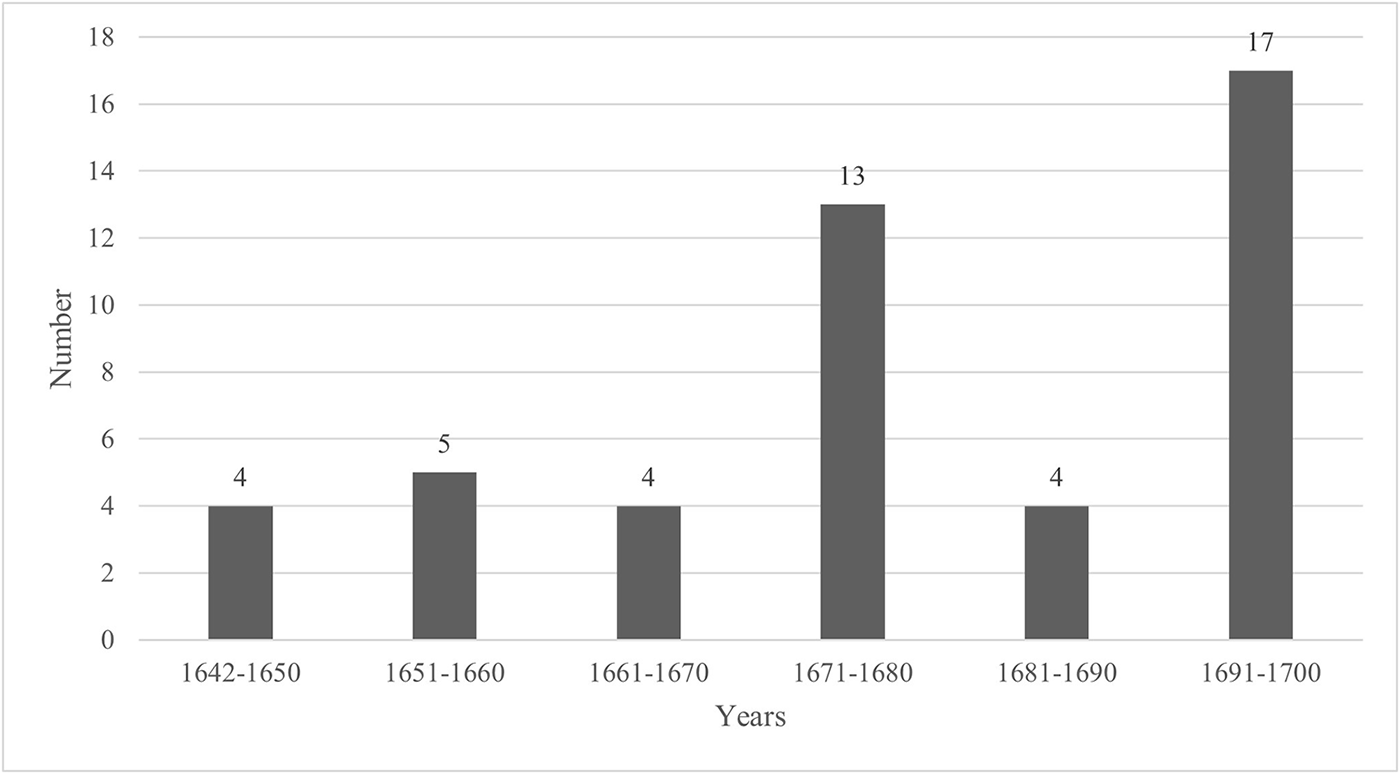

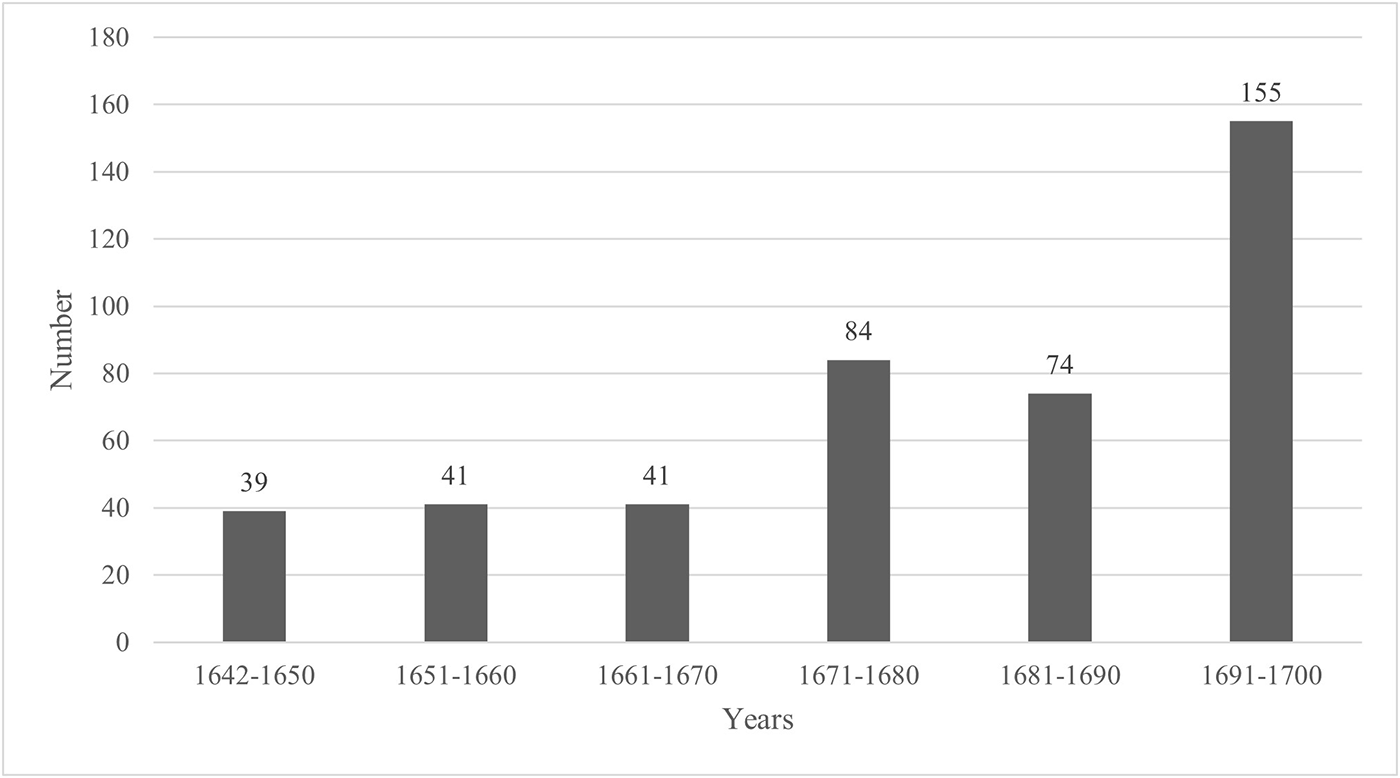

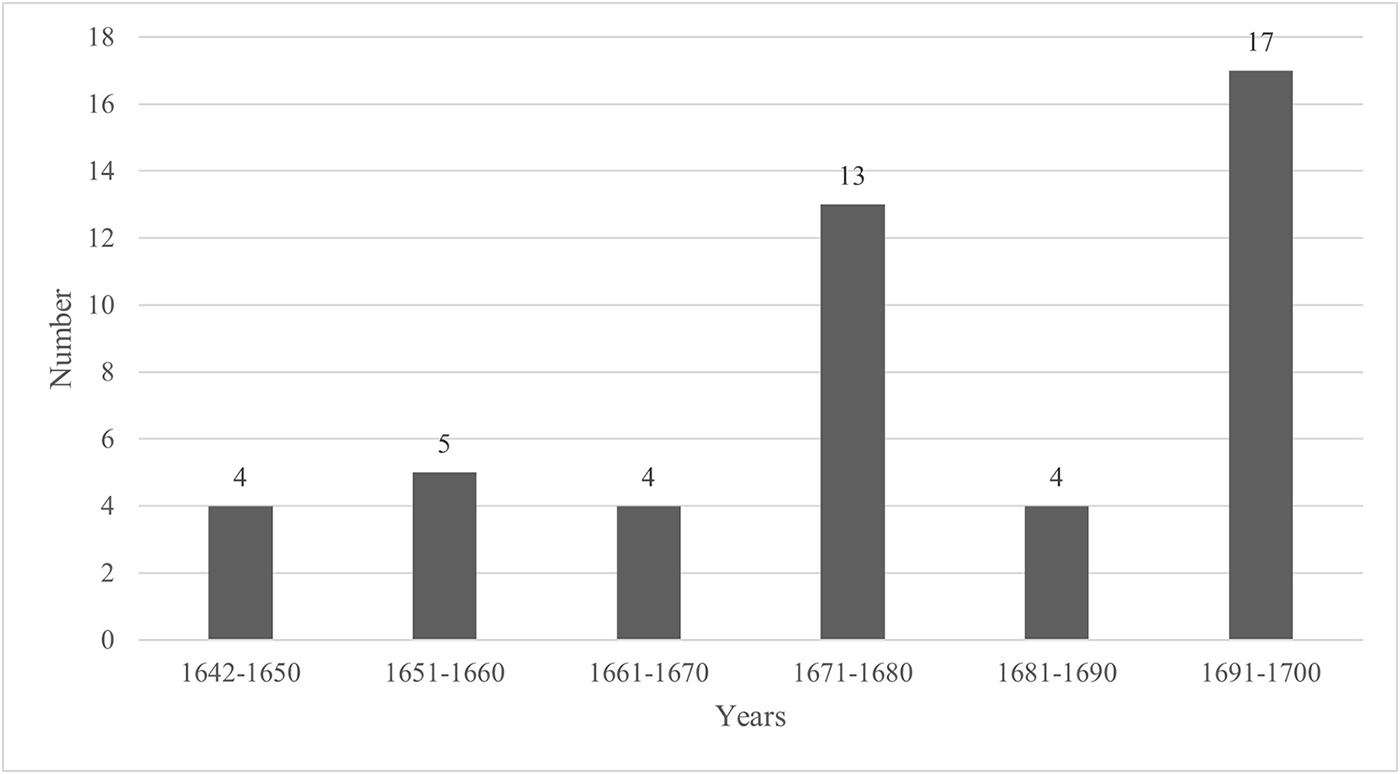

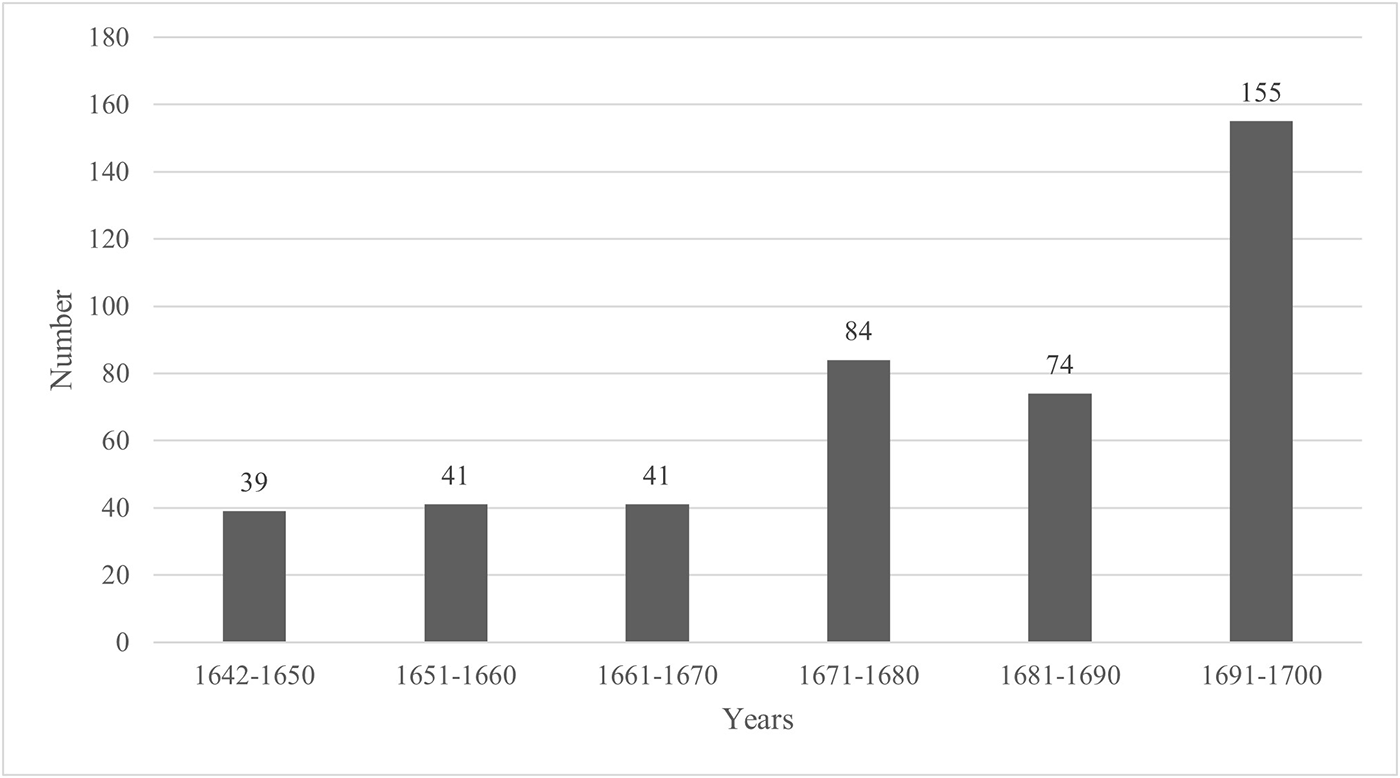

A total of 481 court cases from the period 1642–1700 have been used in the investigation. Out of these, 47 concern outbreaks of wildfire and 434 cases concern applications of fire support (Swe. brandstod) (see Figures 2–4). A sample of these cases has been compared to contemporary tax records, which has made it possible to establish to what degree the monetary or in natura assistance given by peasant communities was enough to enable peasant families to resume the cultivation of their homesteads. The Swedish legislation that has been used is legal codes and forest ordinances that contain information on how wildfires should be counteracted and how to punish those who caused them.

Figure 2. Number of recorded forest fires in North Ostrobothnia during the seventeenth century in ten-year increments. Data source: NAF, Court Records.

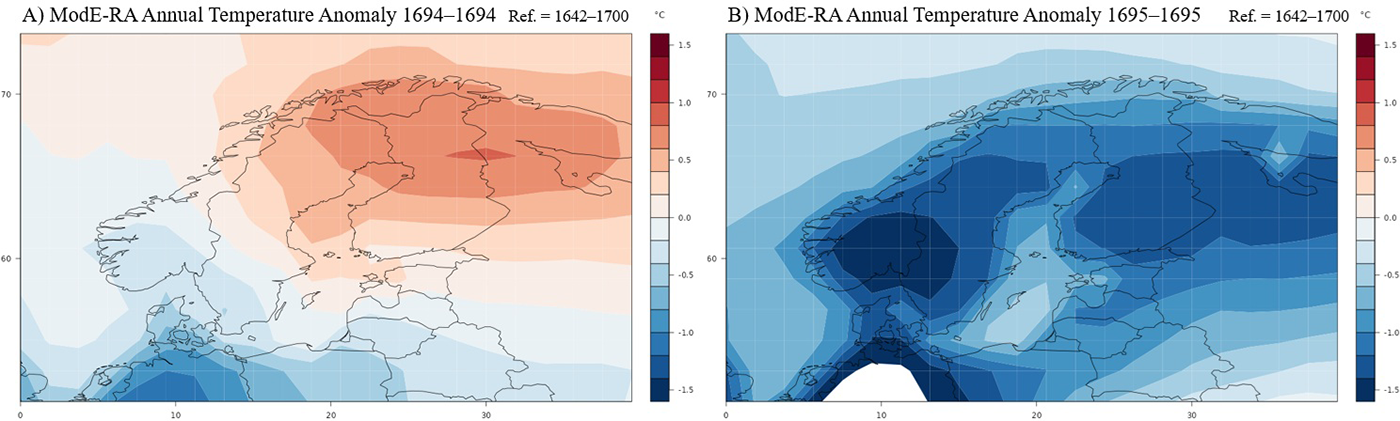

Figure 3. Annual temperature anomaly during the year 1695 to the right and 1694 to the left. Data source: Richard Warren, Niklaus Emanuel Bartlome, Noémie Wellinger, Jörg Franke, Ralf Hand, Stefan Brönnimann and Heli Huhtamaa, ‘ClimeApp: data processing tool for monthly, global climate data from the ModE-RA palaeo-reanalysis, 1422 to 2008 CE’, Clim. Past 20, 2645–2662.

Figure 4. Number of fire support applications in North Ostrobothnia during the seventeenth century. Data source: NAF, Court Records.

The material has undergone quantitative and qualitative analysis. Regarding the former, mentions of wildfires in the court records see an increase during the 1670s and 1690s (see Figure 2). Whilst fire is a natural part of the life cycle of forests, it is easy to establish that these increases resulted from the forest industry in the region.Footnote 48 Nevertheless, climatological variations can also influence the occurrences of wildfire. For example, 13 out of the 17 wildfires during the 1690s took place between 1691 and 1694, after which no wildfires were reported until 1698. In 1695 (Figure 3B), it is possible to identify a clear decrease in annual temperature compared to the year 1694 (Figure 3A). The unusually cold winter of 1694–1695 not only delayed the growing season but also led to a colder and wetter summer, which reduced the risk of drought and fires occurring.Footnote 49 The years leading up to the unusually cold post-1694 years were furthermore emphasized in the court protocols, as producing tar ‘especially in such dry and hot weather’ as in 1693 was considered unwise.Footnote 50

3. Tar production and communal action

The amount of money a peasant family was able to obtain through tar production could be sizeable. As explained by Nils Erik Villstrand, up to 120 barrels of tar could be produced in one year, which could earn the household as much as 300 copper thalers, a sum several times greater than a shipbuilder’s annual income.Footnote 51 The income gained could also be life-saving. The ambition of Swedish kings to be great powers on the European stage of war meant that the need of soldiers was high. Recurring conscriptions burdened the peasantry, and the chances of returning after having served were slim. The money obtained through tar production could be put to good use as peasants could bribe local bailiffs (Swe. fogde) to escape conscription or to simply pay someone to take their place.Footnote 52 Even so, tar production was not a trouble-free enterprise.

Village and parish communities in North Ostrobothnia perceived themselves as such by virtue of their common interests, which were largely influenced by their communal ownership, but also through their joint efforts in producing tar.Footnote 53 The most critical stage of the production process was the distilling, which was an activity carried out in the communal forests, often together with one’s family and neighbours, including men and women, young and old. Once the tar pit (Finn. tervahauta; Swe. tjärgrop) was lit, one had to continuously control the heat so that it did not burst into flames and spread. Not only could the tar wood be consumed but also anything stored at the distilling site, as in the case of Lars Sigfredsson in 1648 whose tar pit (consisting of an estimated 25 barrels) was lost, as well as 36 barrels of finished tar.Footnote 54 Once a fire spread, whatever could be done to extinguish it was paramount, although not easily achieved. In the parish of Pyhäjoki, a particularly devastating and large wildfire spread from one parish to another ‘so that the forest was almost fully engulfed in flames’, destroying vast areas of biomass and several peasants’ tar pits, distilled tar and tar forests.Footnote 55

The reach of an uncontrolled fire was not limited to its flames. Sparks and embers travelled with the wind, ultimately settling down on the highly flammable roofs of buildings, resulting in whole farms being turned into ash.Footnote 56 In the southern part of Kalajoki parish in 1693, a man called Michel Mattsson was supervising one tar pit as it was exposed to an unfavourable wind. It grabbed hold of the flames that ‘had accidentally leaped up to a nearby birch tree, which then fell to the ground, and this he did not acknowledge until it began to spread, which he alone did not have time to put out’. Even though he had ‘cried for help, it had taken over before the people could come’ and the fire thereafter spread throughout the forest to consume the tar of the other peasants in the area.Footnote 57 Another particularly tragic example occurred 15 years earlier. The peasant Henrik Olsson explained to the court how a great fire had caused him great misfortune as it had destroyed his tar pit and tar wood but also the cabin (Swe. pörte) in which he lived during the distilling process. What was even worse was that his son and servant girl (Swe. piga), who were inside the cabin at the time, suffered such injuries that they soon after died.Footnote 58 Events of wildfire as tragic as that one are not uncommon in the court records, meaning that the hazard of tar production was something that peasants knew well. Nevertheless, tar production had become a customary economic practice, and the positive outcomes of this industry outweighed the negatives on a general level.Footnote 59 Like the Campine commons providing commoners with vast heathlands and ‘ghost acres’, North Ostrobothnian peasants were able to diversify their income and make a living through land cultivation and tar production.Footnote 60

As mentioned earlier, the local court was the collective-choice arena in which commoners could solve issues related to fire outbreaks and decide how to collectively fight and prevent fires from spreading. For example, in mid-August 1691, two peasants stood accused of having started a fire in the forest on the 12th of July that summer, which had spread beyond their control. Even though they denied it forcefully, several other peasants testified to their guilt. The fire had caused great damage to both infields and the forest, destroying large amounts of tar wood that were about to be distilled by peasants in the area. Furthermore, the fire was still raging as the discussion took place in the courtroom. The court records reveal how the laymen of the court, the chief constable and the peasants that had gathered immediately went ‘to the fire with every man in the villages, to endeavour to subdue and extinguish it’.Footnote 61

As the previous case clearly demonstrates, the local court served as an important node for the rural population during the seventeenth century. As much as one-third of the local population attended the court meetings, which meant that word of what transpired there, and the decisions taken, spread quickly throughout the parish.Footnote 62 These meetings were therefore important and useful collective-choice situations where commoners could address communal problems and either encourage or dissuade people from practices deemed harmful or wrongful. For example, in terms of forest management, commoners discouraged each other from debarking and cutting pine trees that were too young, since it was considered wasteful.Footnote 63 In a similar manner, discussions also took place concerning how to carry out and organize tar production in correct and safe ways to limit the risk of fires breaking out. For example, tar production during ‘dry and hot weather conditions’ was questioned, discussed and discouraged at a court meeting in Kalajoki in August 1693.Footnote 64 Furthermore, considering that the tar distilling process could last for several days, discussions were also held concerning the number of people that should supervise the tar distilling process at any given time so that the tar pit did not catch fire.Footnote 65 The matter of weather conditions had been discussed 15 years earlier in the same parish when the peasant Sigfred Tulpa had caused a fire that he ‘was unable or incapable of extinguishing in the great drought that was then present’.Footnote 66 Whether or not the two events shared any connection is difficult to determine, but it is possible to establish that the collective-choice and problem-solving arena of the local courts functioned as a platform upon which commoners could raise issues and discuss problems related to tar production, thus incentivizing each other to act in a manner that reduced the risk of fires occurring. As explained by Tine de Moor, structures within which commoners partake and contribute to decision-making processes of common-pool institutions ‘are more likely to survive because “being involved” enhances reciprocal behaviour’. Therefore, considering that matters of fire management, as well as the management of forest commons, were discussed in the same collective-choice setting (the local court) where commoners were involved in the communal decision-making process, the level of resilience of their communities increased because of the institutional framework of their communal ownership structure.

4. Swedish forest laws

The ability of peasants to recover from fire disasters was influenced by the rules of their communities as well as by legislation instituted by the central government. In the Swedish Kingdom, laws touching upon wildfires had been decreed long before the seventeenth century, primarily in the Medieval Scandinavian Provincial Law and the Construction Law. However, new forest legislation was passed during the seventeenth century, as was the case in many European states from the sixteenth century onwards.Footnote 67 In 1647 and 1666, two forest ordinances were decreed, parts of which contained instructions on how to deal with issues related to wildfires. They stated that if a wildfire or forest fire had been caused by mistake, the culprit would pay a fine of 20 marks and compensate the other landholders for the damage the fire had caused. Had it been done with intent, the offender ‘would pay, if he is captured, with his life’.Footnote 68

As pointed out by Paul Warde, ‘laws were not newly invented responses to whatever challenges perceived’. Rather, their origins can be traced through a long line of domestic legislation, often influenced by that of neighbouring states.Footnote 69 Whilst the Swedish ordinances were comprehensive, they did not contain instructions on how to prevent a fire from spreading, or how to prevent it from happening altogether. Because of this deficiency, the Swedish Crown issued a forest fire ordinance on the 10th of December 1690, proclaiming that the forests, ‘of which our kingdom … to a large extent has its origin and function’, are being increasingly devastated by forest fires caused through ‘negligence and carelessness’. Thus, the new laws were to serve as legal tools with which officials could better punish those who had caused such devastations, but also as instructions on how wildfires ‘with caution and power can be subdued and extinguished’.Footnote 70

The new ordinance was made public in North Ostrobothnia in early 1691. The peasantry was given a detailed instruction on how to act if a fire was detected. Those who first took notice of the fire should call upon their neighbours to assist in putting it out. If the fire was spreading quickly, the peasants should let the bidding stick pass from village to village so that everyone would know that there was a fire looming.Footnote 71 Should they fail in this, they would be fined 20 silver thalers (which was a large amount considering that a peasant accrued approximately 85 copper thalers, or roughly 28 silver thalers, in one year)Footnote 72 or suffer the gauntlet. A gauntlet was when an individual was sentenced to run between a double file of men facing each other and armed with clubs or other weapons with which the individual running was beaten. At least one man from each household in the surrounding area was told to assist in extinguishing the fire, and if there were enough people, one should run and inform the chief constable and one should go to the closest church and ring the church bell. Detailed instructions were given on how the chain of command should be organized and how axes, spades, buckets and other necessary implements should be provided by all who had such tools at hand. Everyone was instructed to do ‘all they can and have time to do … to suppress the fire, and to either fell trees or dig and remove all that may nourish the earth fire’.Footnote 73

There are several cases where peasants were fined extraordinarily high amounts for causing a forest fire, which can also be found in legal records from the Swedish mainland.Footnote 74 In Örebro county in 1715, for example, two peasants were fined 100 silver thalers each. However, since they were unable to pay, they were instead sentenced to run 13 times between a double file of 100 men who beat them with clubs or other weapons. Comparably, in the county of Dalarna, 32 individuals were sentenced to pay 3,200 silver thalers for a similar crime.Footnote 75 Whilst transgressions against the forest regulations can be interpreted as an expression of social protest (such as exceeding the permissible limit of forest exploitation),Footnote 76 breaking the forest fire law was a matter of life and death, and it was considered highly shameful and criminal not to help when a fire was raging. Even if a fire did not threaten to consume someone’s home at a certain instance, it very well could the next time. The ordinance thus stipulated that ‘as long as the fire persists, none of those who have congregated shall be allowed to leave until everything is well extinguished and permission is given’.Footnote 77

The court cases from the 1690s have demonstrated how the forest fire ordinance was adopted by local courts in North Ostrobothnia. This conclusion can be contrasted with results gained from dendrochronological research in Sala in Västmanland County in central Sweden. Whilst the period 1490–1690 saw frequent fires, the post 1690-period only saw traceable fires during particularly dry years.Footnote 78 Whilst this could be explained by climatic conditions, it is striking that this was the year when, up until that time, Sweden’s most comprehensive and detailed forest fire ordinance was decreed on how to prevent and combat fires from occurring.

When wildfires occurred, top-down measures were not always enough. To achieve an effective management of extinguishing fires, bottom-up measures were often more attuned to local circumstances. As argued by Bas van Bavel et al., ‘agricultural systems, settlement location, and construction methods were often adapted to the natural environment to minimize risks’. In this context, the structure of communal management facilitated such efforts, as entire communities, with expert knowledge of local conditions, could effectively work together to avoid possible disasters and mitigate the subsequent negative outcomes.Footnote 79 We should ask if the legislation decreed facilitated or hampered the ability of North Ostrobothnian peasant communities to ‘bounce back’ after a fire disaster, and whether or not it produced vulnerable people.Footnote 80 A possible argument is that the external assistance given, and forceful punishments decreed by the state, demonstrate a weakness and vulnerability in the peasants’ common-pool institutions, that is, that they were less able to withstand these shocks on their own. However, as pointed out by Jane Mansbridge, polycentric systems of governance are often facilitated by the state’s involvement.Footnote 81 Furthermore, Tobias Haller et al. have shown how common-pool institutions in Switzerland were essential in the implementation of laws among commoners.Footnote 82 If so, the institutions should be seen as indicators of the resilience of the society in which they lived. The instruction given on how to fight the spread of a fire was grounded on close cooperation amongst everyone who lived in the area: peasant and state official alike. The punishment for not complying was a clear indicator that the welfare of the forests was not just the responsibility of one individual or group but that of all. As such, the efforts of the Swedish state were by all things considered to be facilitating factors in the peasants’ ongoing struggle to minimize the number of fire disasters, as well as their negative outcomes.

5. Accident or carelessness?

Wildfires did not respect boundaries, nor did they respect rules of ownership. Establishing whether a fire had been caused by accident or carelessness was important. If a fire had started in a tar pit and spread to the surrounding forest, the person who had caused it was held responsible to all suffering parties. For example, in Pyhäjoki parish in 1678, Johan Hindersson accused his neighbours Anders Andersson and Bertil Matsson of having caused a fire in their tar pit, consuming Johan’s 100 loads of tar wood. The two peasants confessed that they had caused the fire but maintained that they had put it out. Another peasant by the name Olof Olsson testified to Anders and Bertil’s story, confirming that they had indeed put out the fire with three fathoms of water. Even though Olof’s testimony spoke in Anders and Bertil’s favour, the court suggested a voluntary settlement where they should give Johan five barrels of tar, which they agreed to.Footnote 83

The prevailing attitude towards fires that had started by accident and those that had started by carelessness differed on the point that the former was considered to be of less fault on the part of the accused. A peasant who had suffered from a fire that someone else had accidentally started could also take this attitude, thus indicating that a certain level of understanding concerning the precarious nature of tar production prevailed between peasants. In Pyhäjoki parish in 1678, Enut Christersson explained to the court how his neighbours Henrik Sigfredsson and Erik Jöransson had reduced 180 loads of his tar wood to ashes when they had let the tar pit that they shared go up in flames. They did not deny this but added that ‘the fire had been set loose by accident and could not be extinguished’, and that they had lost 24 barrels of tar. Enut admitted that he understood that ‘his neighbours by no means willingly did this’ and the court therefore decided that Henrik and Erik should only reinstate one-quarter of what Enut had lost, adding up to six barrels of tar.Footnote 84

As mentioned earlier, carelessness was not kindly received, especially if the damage caused was significant. This demonstrates not only the importance of forest resources but also how disastrous the consequences of a wildfire could be. An example of this is the case of Henrik Bertilsson Raumala who on Midsummer Eve 1693 had walked through the forest together with Pål Pålsson. After a while, they decided to sit down and smoke some tobacco and Pål therefore lit a fire. Soon, the area around them was caught by the flames and the fire quickly spread. The chief constable and a few laymen had inspected the damage and concluded that it had affected five peasants who lived in the area where Henrik and Pål had been walking. Between them, the damage included 85 ship planks (Swe. vränger), 24 loads and 20 fathoms of tar wood, 20 fathoms of firewood and one tree trunk intended for house construction. The value was estimated to be 76 copper thalers. The misfortunate event ultimately led the court to charge the defendants with reinstating those who had suffered from the fire and to pay a fine of 30 silver thalers. They considered the punishment to be reasonable since ‘this damage was caused by carelessness’ and their intentions did not include the ‘lighting of swidden’. In other words, had they claimed, or in any way been able to prove, that the fire was caused by some accident connected to slash-and-burn agriculture, the punishment would have been less harsh.Footnote 85

6. Brandstod: fire support

To determine the degree to which Ostrobothnian peasant communities were able to recover from fire disasters, we need to look more closely at the help available to those affected by a fire. The early modern period saw many new laws and initiatives aimed towards aiding those in need, such as the poor. This can be exemplified by the Elizabethan Poor Laws instituted in 1597 and 1601, which instructed that donations should be given to the deserving poor, which were based on taxes collected from villages and towns.Footnote 86 In the Netherlands and France, poor relief systems were based on ‘benevolent societies’, such as the Daughters of Charity, whereas poor relief was collected through land and rent revenues in the Campine, Belgium.Footnote 87 But help was also available when people suffered from catastrophes. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, large sums of money were collected to help the most vulnerable and to reinvigorate commerce, which facilitated the preservation and re-establishment of socio-economic functions within the city, something that can be compared to the fire of Valencia in 1447.Footnote 88 In terms of fire disasters, so-called mutual societies existed in Britain during the early modern period, such as the Hand-in-Hand, the Union and the Westminster, all founded between 1696 and 1717 and acting as the main fire insurers until the early nineteenth century.Footnote 89

In the Swedish Kingdom, the institution of fire support (Swe. brandstod) is believed to originate from twelfth century Scania and was later established in the Country Law of Magnus Eriksson during the 1350s.Footnote 90 It stipulated that ‘In whatever hundred such [fire] damage has occurred, as has now been said, the hundred owes him fire support, as the damage is estimated’. Earlier research has labelled this system the ‘cradle of the Swedish half-public mutual fire and property insurance organisation at the countryside’.Footnote 91 However, the system was not based on pre-paid premiums and rural communities did not form anything resembling insurance companies. Magnus Eriksson’s Law of the Realm stipulated that everyone had to ‘give fire support, who are residents, clerics, and laymen, and likewise the members of their household’ and that ‘[n]o one should be free from this’.Footnote 92 This stipulation was later revised in King Christopher’s Land Law in 1442 and later found its way into the Beggar Regulation of 1642, which declared that ‘if someone has suffered from fire and wildfire, that person should … properly prove the damage before the district court’ before being able to receive help from the parish community.Footnote 93 In other words, the institution of fire support was a stand-by financial mechanism based on reciprocity to compensate for losses owing to fire damage. The damage intended in the laws was primarily damage to the farm, houses and other buildings, grain, fodder, livestock, household and personal items. As such, damage to the forest was not covered. However, the court records from North Ostrobothnia show that financial support was sometimes provided anyway.Footnote 94

In total, 434 cases have been found that concern the application of fire support between 1642 and 1700 (see Figure 4). As explained by Pentti Virrankoski, a person who had suffered from a fire could apply for fire support in the form of tax relief. However, this had only been used sporadically until the reign of Gustav II Adolf (1611–1632).Footnote 95 In North Ostrobothnia, the number of cases concerning wildfires shows a clear correlation with the number of fire support applications (see Figures 2 and 4). However, wildfire did not always precede an application. Poorly built houses could burn down during storms as the wind could penetrate the walls and cause flames and embers to spread from the fireplace, or because of the poor quality of chimneys.Footnote 96 Nevertheless, most applications were granted given that a proper investigation had preceded the court visit, and that carelessness had not been the initiating cause of the fire.

The extent of the burnt areas is rarely stated in the court records. Instead, the extent of the damage to finished or semi-finished products, animals and buildings is specified. The most common way to receive help was in the form of monetary contributions. This could also be combined with other forms of assistance, such as help with reconstructing buildings or foodstuff, which was also the case in central Sweden.Footnote 97 By calculating the average extent of damage and aid given in North Ostrobothnia during the 1680s,Virrankoski estimated that as much as 63 per cent of the value was reinstated. However, the amount of money granted varied depending on social status, since clergymen, for example, sometimes received more compensation than the actual value of what had been lost.Footnote 98 By instead focussing on cases when tar had been lost and considering its value at the time in relation to the compensations given, the average compensation was approximately one-third of the value lost.Footnote 99 In other circumstances, the size of contributions could vary greatly. In the case of Henrik Olsson discussed earlier, he was granted a total of 20 copper thalers in 1678.Footnote 100 In 1698, Carin Simonsdotter, a soldier’s widow, appealed to the court as her farm had burnt down, at which time ‘her father-in-law, husband, brother-in-law and many other very useful and irreplaceable persons for the household, with death having departed, so that she alone with a few small children remained’. She was granted fire support from the parishes of Siikajoki and Saloinen, amounting to roughly 150 copper thalers.Footnote 101

Another way to determine whether the institution of fire support made it possible for peasant families to resume the cultivation of their homesteads is by analysing contemporary tax records. During the early modern period, the main economic burden for peasants was to pay taxes to the crown, which continuously increased throughout the seventeenth century.Footnote 102 If a household was unable to pay taxes for three years in a row, it was marked as ‘deserted’ (Swe. öde) in the tax records and most families were evicted. Thus, a ‘deserted’ marking signals a decline in subsistence.Footnote 103 Since the court records contain the name of the fire support applicants, the date of the fires and the money received in fire support, the effectiveness of the fire support institution in reducing levels of vulnerability can be determined. This has been done by examining whether the applicants continued to pay their taxes more than three years after the fire event. Of the 434 fire support applications, 143 applications (33 per cent) were chosen at random. Similar to compensations for damaged forest products, the average compensation was one-third of the property lost. Unfortunately, the person registered in the tax records and the applicant of the fire support was not always the same person (the applicant could, for example, be the son or wife of the person registered in the tax records). Nevertheless, the fate of 57 families was confirmed (40 per cent), and the investigation showed that only three households (5 per cent) were marked as deserted up to five years after the reported fire disaster.Footnote 104 This demonstrates that the help given by the parish community was in most cases enough, that the vulnerability of individual peasant households was lowered by the fire support institution and that the level of resilience of peasant communities was consequently strengthened by these measures.

Communality and reciprocity were two important elements of daily interaction and exchange between people,Footnote 105 and people perceived it as natural to aid those who had fallen on hard times since, after all, no one knew when their turn would come. Nevertheless, the particular circumstances of each case were important to consider. In 1693, for example, the peasant Michel Mattsson was convicted for having instigated a forest fire that had caused enough damage to the communal forest that the other commoners had reason to claim compensation. However, one of the affected peasants instead asked the court if Michel could receive financial help on the grounds that he was a poor man who ‘could not possibly afford to compensate for the damage’. The laymen of the court and the gathered peasantry emphasized that Michel was a hardworking, productive and pious man who could not be accused of having caused this fire on purpose. The court therefore decided to grant him fire support. The last part of the record includes a sentence that demonstrates the goodwill that persisted among peasants: ‘Thus, one cannot reasonably refuse them of their own will to give to whom they please, so the jury and the parishioners in each locality shall assist in obtaining this voluntary grant’.Footnote 106

As mentioned earlier, the fire support institution in the Swedish Kingdom was a stand-by financial mechanism based on reciprocity and shared a likeness with relief systems available in the Campine.Footnote 107 The redistribution and aid mechanism of fire support was mandatory, meaning that when someone was deemed deserving, everyone in the parish had to contribute no matter their social or financial standing. Still, support was given even when it had not been decreed by the court. The conditions were even such that whilst each parish was obliged to support their own members, several cases have demonstrated that aid was given by other neighbouring parishes as well, even though this was not mandatory.Footnote 108 Not only is this evidence of the polycentric and nested character of North Ostrobothnian peasant communities,Footnote 109 but the vital aid given to those in need also demonstrates the robustness of the peasants’ common-pool institutions. As such, the level of communality reduced vulnerability and increased the ability to recover from fire disasters and personal economic ruin, thus increasing the level of resilience.

7. Conclusion

The purpose of this article has been to present and discuss how peasant communities were affected by fire disasters in North Ostrobothnia during the seventeenth century, and to explain how community, solidarity and reciprocity behaviours increased their resilience and ability to recover from such events. A bottom-up and top-down perspective has been used to present different factors of resilience and vulnerability, made possible by the analysis of local district court protocols, tax records and Swedish legislation. Through the peasants’ practice of tar production, the number of fire disasters increased in North Ostrobothnia, which made peasant communities increasingly vulnerable. Yet, the income gained had become a fundamental part of the peasants’ household economy, and the level of vulnerability therefore had to be reduced by resilience-boosting counter-measures. Below are the three most significant factors of resilience that have been identified.

The first factor of resilience was the community, solidarity and reciprocity behaviours reinforced by the common-pool institutions they shared. Collective action and goodwill towards members of the community that had fallen on hard times were characteristic elements of their communities, and the communal ownership regime structuring their industrious activities and daily life defined what they perceived to be the common good. Peasants cooperated in the production of tar and made collective decisions on how to manage the exploitation of their forests, including how to collectively act when a fire was raging, how the consequences of fire disasters should be dealt with and how support should be given to those deemed deserving. Ultimately, this increased the level of resilience in their communities and helped them overcome recurrent episodes of fire disasters.

The second factor of resilience was the relationship and cooperation that existed between peasant communities and Swedish authorities. The local courts were the place where peasants and state representatives met to investigate and evaluate the scale of the damage caused by wildfires, their causes and the level of compensation. Furthermore, the new legislation of the seventeenth century emphasized very clearly the importance of cooperation between the rural population and local officials to mitigate the negative socio-economic consequences of fire disasters. As such, their shared perception in these endeavours created conditions where they could work towards implementing rules and strategies aimed at limiting the occurrences of fire disasters, which ultimately reduced the level of vulnerability. These findings resonate with, for example, Swiss commons research that has similarly emphasized the importance of cooperation between state representatives and common-pool institutions in law implementation.Footnote 110 However, the results furthermore give new insights concerning the importance of local courts functioning as conflict-solving arenas and nodes for addressing communal problems related to fire disasters and the implementation of risk-reducing behaviours.

Focussing on the victims is important to establish whether a society was resilient by investigating to what extent people were exposed to suffering and disruption, and whether some benefitted whilst others suffered.Footnote 111 The third factor of resilience is determined by the ability of peasant communities to recover from fire disasters and return to a former structure of organization and management, and in doing so, not produce vulnerable and exposed people. In this context, the North Ostrobothnian case shows how the institution of fire support was reinvigorated during the seventeenth century and was able to restore peasant households. Even though large sums of money were collected and distributed to the misfortunate victims of catastrophes such as the Great Fire of London, the institution of fire support stands out in functioning as a stand-by socio-economic safety net large enough to get most people back on track.Footnote 112 Furthermore, voluntary donations were often given by several parish communities even when the court had not granted fire support and despite it not being stipulated by any legal code, which demonstrates a high level of empathy and communality amongst peasant communities.

In this way, and in sum, peasant communities in North Ostrobothnia were able to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience through community, solidarity and reciprocity behaviours, through the use of Swedish laws and cooperation with state officials, and through the institution of fire support. The significance of these findings is not only that early modern rural communities were more accustomed to recurrent episodes of fire disasters than previous research has shown. Equally significant is how they were able to overcome these tragedies by relying on the communal ownership regime that structured their lives and livelihoods, and by actively participating in and utilizing the legal system, thereby contributing to make their communities more resilient.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks PhD students Niklaus Bartlome and Richard Warren at Bern University, Switzerland, for assisting in providing the annual temperature figures through the data processing tool of the state-of-the-art ModE-RA Global Climate Reanalysis ‘ClimeApp’, which they created (https://mode-ra.giub.unibe.ch/climeapp/). The author thanks Prof. Dr Heli Huhtamaa at Bern University, Switzerland, for reading the manuscript and for funding the author’s project ‘Environmental hazards and impact on the management of commons during the early modern period’ through the SERI-funded ERC Starting Grant project ‘Climatic impact and human consequences of past volcanic eruptions’ (VolCOPE) and the SNSF-funded Ambizione project ‘Distal socio-economic impacts of big volcanic eruptions in 1500–1900 CE Switzerland and Sweden’ (DEBTS).

Competing interests

The author declares none.