Negative neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as apathy (characterised by the loss of motivation to participate in activities, social withdrawal and emotional indifference), blunted affect and alogia, are a core feature of Alzheimer’s disease, and constitute a behavioural dimension independent of depression and cognitive status. Reference Reichman, Coyne, Amirneni, Molino and Egan1–Reference de Jonghe, Goedhart, Ooms, Kat, Kalisvaart and van Ewijk3 Patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) also manifest negative neuropsychiatric symptoms. Reference Hwang, Masterman, Ortiz, Fairbanks and Cummings4 Negative symptoms contribute substantially to the huge personal and economic costs of dementia: they are associated with functional deficits, Reference Benoit, Andrieu, Lechowski, Gillette‐Guyonnet, Robert and Vellas5 and a rapid course of both cognitive and functional decline. Reference Landes, Sperry and Strauss6,Reference Lechowski, Benoit, Chassagne, Vedel, Tortrat and Teillet7 Additionally, caregiver burden and distress has been significantly associated with the presence of negative neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia patients. Reference Fauth and Gibbons8,Reference Andrieu, Coley, Rolland, Cantet, Arnaud and Guyonnet9

Negative neuropsychiatric symptoms are also a hallmark of severe psychiatric disorders like schizophrenia. In our previous studies, we demonstrated that fasting peripheral levels of the amino acid proline, a central nervous system (CNS) neuromodulator, Reference Phang, Hu, Valle, Scriver, Beaudet, Sly and Valle10 interact with the activity of the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) enzyme that inactives dopamine, to predict negative symptom outcomes in patients with, Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11 or those at risk for, Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12 psychiatric illnesses. Specifically, the COMT Val158Met functional polymorphism has a direct impact on dopamine levels in the frontal cortex, Reference Lachman, Papolos, Saito, Yu, Szumlanski and Weinshilboum13,Reference Chen, Lipska, Halim, Ma, Matsumoto and Melhem14 and we observed that for patients with the high activity enzyme (COMT Val/Val), high plasma proline was associated with less severe negative symptoms or greater symptom improvement over time, with the opposite finding in those with one or two copies of the low-activity COMT Met allele, who exhibited significantly greater negative symptom severity in the presence of high proline. Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12

Proline is catabolised by the enzyme proline oxidase, encoded by the proline dehydrogenase (PRODH) gene, and study of the Prodh null mouse suggests that elevated proline induces glutamatergic synaptic transmission, Reference Gogos, Santha, Takacs, Beck, Luine and Lucas15,Reference Paterlini, Zakharenko, Lai, Qin, Zhang and Mukai16 and notably, results in increased prefrontal dopamine transmission and functional hyper-dopaminergic responses. A concomitant upregulation of COMT gene expression observed in the CNS, potentially reflects a compensatory response to the activated dopamine signalling in this model. Reference Paterlini, Zakharenko, Lai, Qin, Zhang and Mukai16 Elevated peripheral proline has been associated with multiple psychiatric phenotypes, Reference Clelland, Read, Baraldi, Bart, Pappas and Panek17,Reference Namavar, Duineveld, Both, Fiksinsk, Vorstman and Verhoeven-Duif18 and there is evidence of increased CNS and peripheral proline levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Reference Pomara, Singh, Deptula, Chou, Schwartz and LeWitt19–Reference Trushina, Dutta, Persson, Mielke and Petersen21 Furthermore, while a reduction in dopamine, dopamine metabolites and dopamine receptors have been reported in Alzheimer’s disease (reviewed in Reference Šimić, Babić Leko, Wray, Harrington, Delalle and Jovanov-Milošević22 ), studies have described associations between COMT and psychosis in Alzheimer’s patients Reference Borroni, Agosti, Archetti, Costanzi, Bonomi and Ghianda23 (and reviewed in Reference Perkovic, Strac, Tudor, Konjevod, Erjavec and Pivac24 ), and the Val158Met genotype has been associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms and degeneration within dopamine-innervated brain structures (such as the prefrontal cortex) in patients with multiple dementias. Reference Gennatas, Cholfin, Zhou, Crawford, Sasaki and Karydas25 Given these findings, we tested the hypothesis that dopamine (as assessed via COMT Val158Met) and proline interact to also modify negative symptom severity in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Method

We conducted a cross-sectional study of patients with a clinical diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment with underlying Alzheimer’s biomarkers (MCI+). All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. The protocol was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Review Board (IRB) (numbers AAAR8755, AAAS0071 and AAAV5130), and by the US Army Medical Research and Development Command, Office of Human and Animal Research Oversight. Eligible subjects were identified from participants of Columbia University’s Alzheimer’s and Dementia Research Center (ADRC), Columbia’s Memory Disorders Clinic and from patients under the care of the Columbia Doctors Neurology Aging and Dementia Practice. All subjects were interviewed as to their capacity to provide informed consent (see the supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10926 for additional details), and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Subjects were instructed to fast 8+ hours prior to their on-site single-study visit. Negative symptoms were assessed via the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms in AD (SANS-AD). Reference Reichman, Coyne, Amirneni, Molino and Egan1 Positive PANSS symptoms were also evaluated. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were employed to assess depression and cognition, respectively (see the supplementary material for details on assessment administration). A fasting blood draw was obtained for assay of plasma proline and COMT genotyping, as described. Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12

Demographics, clinical characteristics and medication status were compared across genotypes, and genotype distributions tested for Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). The relationship between negative symptoms, demographics and clinical characteristics, was also assessed. Testing the primary hypothesis of an interaction between COMT and proline on negative symptoms and following the statistical analysis design of our previous study, Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12 we employed Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (Lasso) regression for model prediction, using the double selection feature for testing a priori determined covariates (gender, depression and positive symptoms). Again, as a sensitivity analysis, we employed a post-hoc stepwise selection procedure, starting with the independent variables of proline, COMT and the COMT × proline interaction, plus Lasso retained covariates. Analysis was conducted in Stata/BE v18.0 for Windows (College Station, Texas, USA; https://www.stata.com/). For all tests, the level of significance was fixed at p < 0.05, two-tailed. Benjamini–Hochberg’s corrections were employed to control the False Discovery Rate (FDR, 5%) following use of three negative symptom assessment scales. STROBE reporting guidelines were employed.

Results

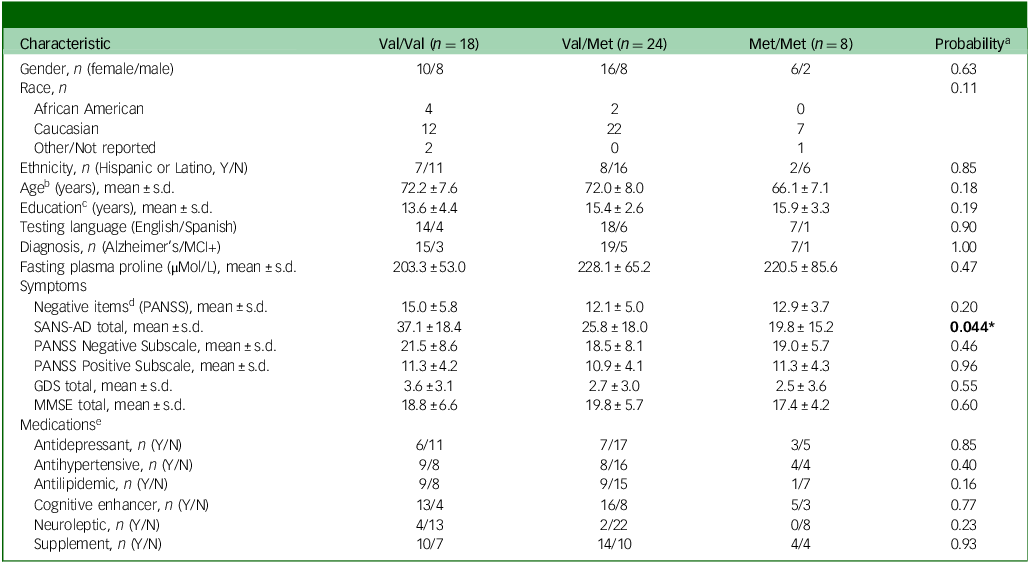

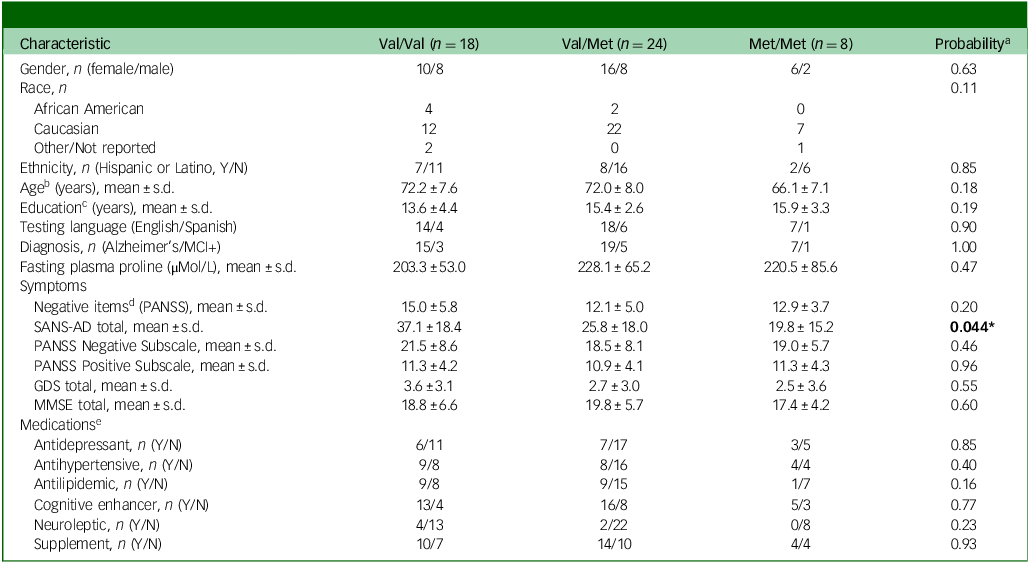

A total of 50 participants completed the study. Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The sample was in HWE for Val158Met (p > 0.05), and genotype groups were well matched. Regarding negative symptoms, there were no differences across genotypes for the negative items of the PANSS (sum of items N1, N2, G7, G8 and G10), Reference Kane, Honigfeld, Singer and Meltzer26 or the PANSS negative subscale (sum of items N1–N7). However, Val/Val subjects had significantly higher total SANS-AD scores (Table 1, p = 0.044) and so as for our previous study of psychiatric patients, Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11 we employed the negative items of the PANSS as the primary outcome assessment, with secondary analyses of negative symptoms using the SANS-AD and the PANSS negative subscale. For all negative symptom assessments, significantly higher scores were observed in Alzheimer’s disease as compared with MCI + dementia (Table 1), and therefore diagnosis was included as a covariate. Further, and as expected, subjects with Alzheimer’s disease had significantly lower MMSE scores compared with subjects with MCI + dementia (Supplementary Table S1, p = 0.0006), and to avoid multicollinearity between the independent but related variables of diagnosis and cognition, diagnosis was chosen as the covariate for all subsequent models.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of the dementia subjects, n = 50

MCI, mild cognitive impairment; PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; SANS-AD, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Bold text indicates a significant difference between groups.

a. Significant p-value (<0.05) when comparing characteristics across three catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype groups, calculated by one-way analysis of variance, Kruskal–Wallis or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All tests were two-tailed.

b. n = 49, as one subject did not report their age.

c. n = 48, as two subjects did not report their years of education.

d. Items N1, N2, G7, G8 and G10 of the PANSS.

e. n = 49, as medication use for one subject was not available. Only medication groups prescribed to ≥10% of the sample (n = 5) are reported.

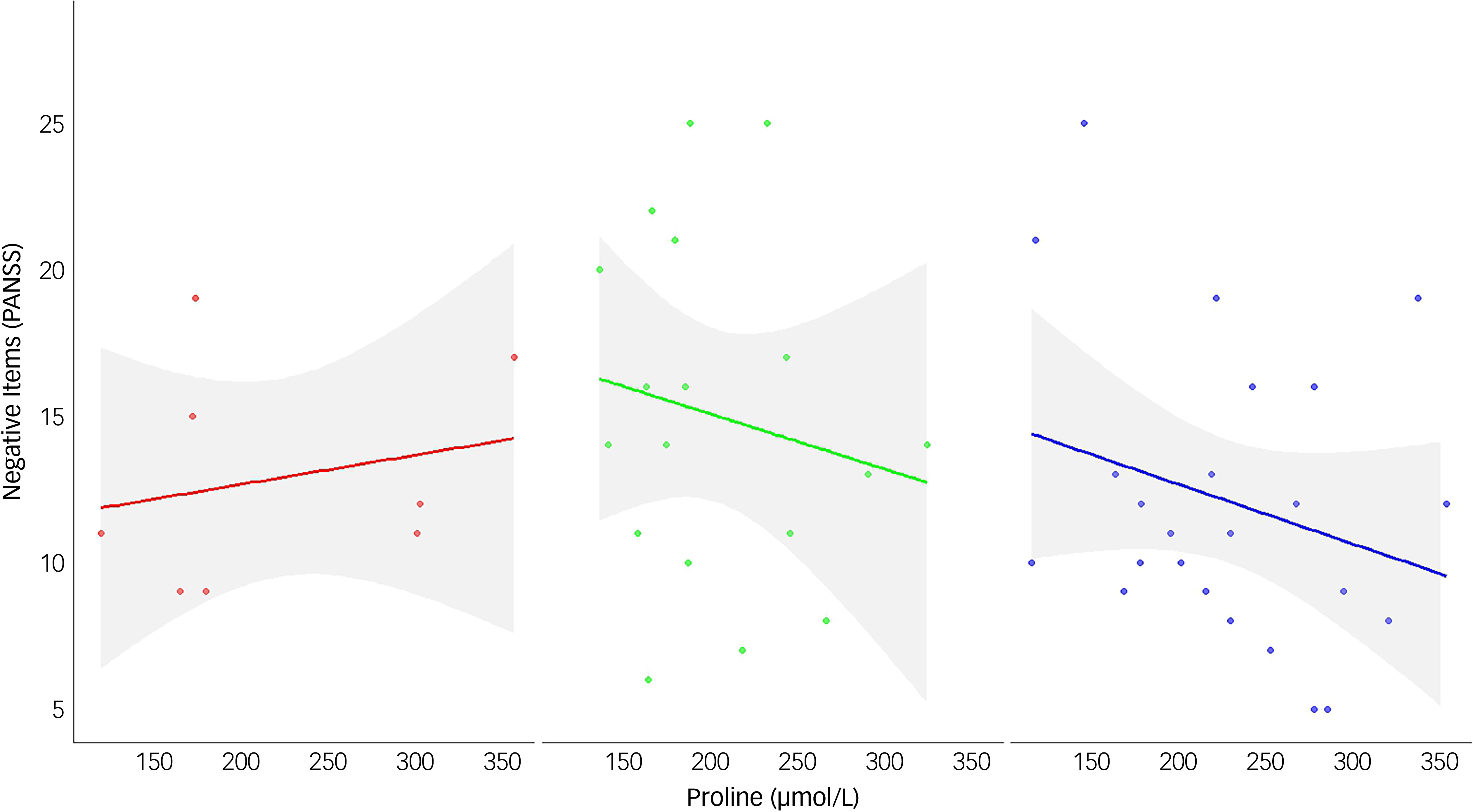

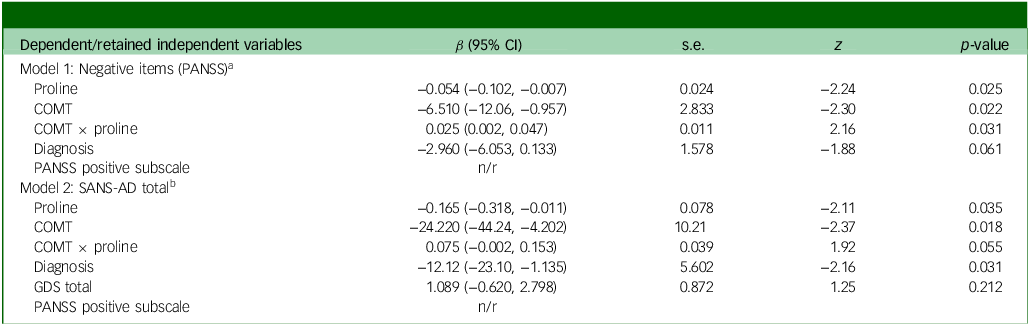

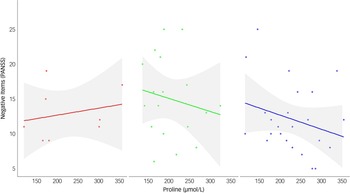

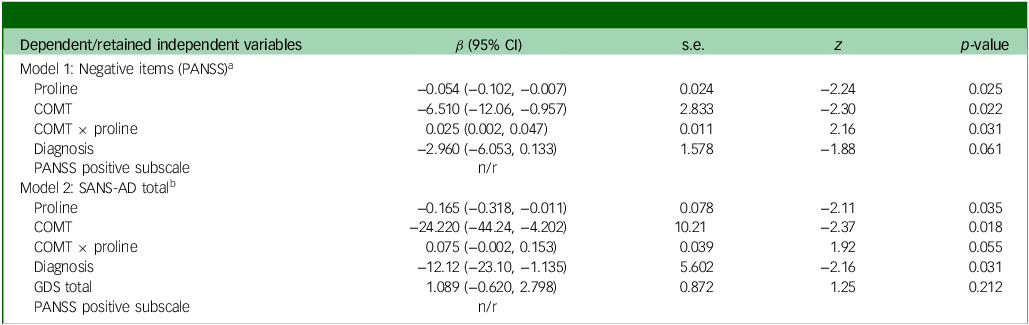

Via Lasso regression modelling, we observed a significant interaction between COMT and fasting plasma proline on negative symptoms (as assessed via the negative items of the PANSS Reference Kane, Honigfeld, Singer and Meltzer26 ), following adjustment for diagnosis and the retained variable of the PANSS positive subscale (Table 1, interaction β-coefficient 0.025, 95% CI (0.002, 0.047), p = 0.031 which remained significant after testing correction). Higher proline was beneficial for both Val/Val and Val/Met dementia patients, but detrimental to Met/Met patients (Fig. 1). In a post-hoc sensitivity analysis the interaction remained significant (Supplementary Table S2), suggesting a robust finding. In secondary analyses, we tested for an interaction between COMT and proline on two additional and highly related measures of negative symptoms, the SANS-AD total score and the PANSS negative subscale; however, although supportive of our primary analysis, the interactions did not reach statistical significance (SANS-AD interaction β-coefficient 0.075, 95% CI (−0.002, 0.153), p = 0.055, Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1; PANSS negative subscale interaction β-coefficient 0.030, 95% CI (−0.005, 0.066), p = 0.093).

Fig. 1 The interaction between catechol-O-methyltransferase genotype and proline on the negative items of the Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) subscale. Data are plotted for each genotype group: Met/Met (left panel, n = 8, red), Val/Val (middle panel, n = 18, green), and Val/Met (right panel, n = 24, blue). Regression lines represent predicted values from simple linear models, with shaded areas indicating 95% confidence intervals. Among individuals with the Met/Met genotype, higher proline levels (x-axis) are associated with more severe negative symptoms (y-axis). In contrast, an inverse relationship is observed in both the Val/Val and Val/Met groups, where elevated proline levels correspond to fewer or less severe negative symptoms.

Table 2 Prediction of negative symptoms by the COMT × proline interaction, n = 50

COMT, catechol-O-methyltransferase; s.e. of β; z, critical value; PANSS, Positive and Negative Symptom Scale; n/r, point estimates of retained covariate(s) not reported in Lasso model; SANS-AD, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms in AD; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale.

a. Model 1, Wald χ 2(4) = 10.14, p = 0.0382. Independent variables: COMT (ordinal Val/Val, Val/Met, Met/Met), proline (continuous), interaction (COMT × proline), diagnosis (binary). Covariates: GDS total score (continuous), gender (binary), PANSS positive subscale (continuous).

b. Model 2, Wald χ 2(5) = 23.94, p = 0.0002. Independent variables: COMT (ordinal Val/Val, Val/Met, Met/Met), proline (continuous), interaction (COMT × proline), diagnosis (binary), GDS total score (continuous). Covariates: gender (binary), PANSS positive subscale (continuous).

Discussion

In this proof-of-concept study of patients with Alzheimer’s disease or MCI dementia with underlying Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, we observed that levels of the CNS neuromodulator proline and COMT Val158Met genotype interact to predict negative neuropsychiatric symptoms. As for our studies of patients with severe psychiatric illness Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11 and those at risk for psychosis, Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12 higher proline was beneficial for Val/Val dementia patients, but detrimental to those with the Met/Met genotype. Interestingly, in this first study of dementia patients, high proline was also found to be beneficial for Val/Met patients, which is somewhat inconsistent with our prior findings on psychiatric patients. Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12

Elevated plasma proline (hyperprolinemia) has been linked to a range of neuropsychiatric phenotypes, including developmental delay and intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, psychosis spectrum disorders Reference Clelland, Read, Baraldi, Bart, Pappas and Panek17,Reference Namavar, Duineveld, Both, Fiksinsk, Vorstman and Verhoeven-Duif18 and Alzheimer’s disease. Reference Pomara, Singh, Deptula, Chou, Schwartz and LeWitt19–Reference Trushina, Dutta, Persson, Mielke and Petersen21 Further, in patients with 22q11 deletion syndrome, who routinely exhibit elevated proline due to hemizygous deletion of the PRODH gene on chromosome 22, negative neuropsychiatric symptoms show opposing severities by COMT allele. Reference Vorstman, Turetsky, Sijmens-Morcus, de Sain, Dorland and Sprong27–Reference Schneider, Van der Linden, Glaser, Rizzi, Dahoun and Hinard31 Taken together, we suggest a common mechanism across neuropsychiatric disorders, as previously proposed Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12 : specifically, for Met/Met patients in the presence of high proline, a potential increase in dopamine transmission in the prefrontal cortex is exacerbated by low COMT activity, ultimately resulting in a frontal dopaminergic state above optimal levels. Conversely, in Val/Val patients, higher prefrontal COMT activity would likely reduce dopamine, limiting dopamine-receptor-mediated excitation, Reference Bilder, Volavka, Lachman and Grace32,Reference Tunbridge, Harrison and Weinberger33 and leading to potential prefrontal hypodopaminergia. Thus, higher proline would be beneficial for Val/Val patients, via shifting prefrontal dopamine signalling to optimal levels. In this model, and as speculated, Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12,Reference van Duin, Ceccarini, Booij, Kasanova, Vingerhoets and van Huijstee34 negative symptoms would be induced in conditions of both hyper- and hypo-dopaminergia, reflecting the inverted U-shape curve proposed for cognitive dysfunction in psychosis, Reference Tunbridge, Harrison and Weinberger33 executive function in Parkinson’s disease Reference Fang, Tan, Tu, Liu and Yu35 and the opposite impact of dopamine receptor availability on cognitive and motor performance in Alzheimer’s disease. Reference Reeves, Mehta, Howard, Grasby and Brown36 It is interesting to speculate that reduced catecholamine levels in the ageing cortex, Reference Kalbitzer, Deserno, Schlagenhauf, Beck, Mell and Bahr37,Reference Zanto and Gazzaley38 may dampen the impact of elevated proline, particularly for those patients with the Val/Met genotype who have intermediate enzyme activity, resulting in the unexpected finding of a negative relationship between high proline and less severe symptoms in heterozygotes.

Regarding limitations, one key limitation of this study is the sample size; as completion of 50 participants in total resulted in relatively small genotype groups. However, this first investigation of dementia patients builds positively from our previous studies. Although the COMT × proline interaction did not reach statistical significance for all negative symptom assessments, we did observe a significant interaction using the negative items of the PANSS, the one assessment that was used across all our studies, Reference Clelland, Drouet, Rilett, Smeed, Nadrich and Rajparia11,Reference Clelland, Hesson, Ramiah, Anderson, Thengampallil and Girgis12 with interactions trending towards significance when measuring negative symptoms via the SANS-AD total score and the PANSS negative subscale. The SANS-AD was specifically designed for research with dementia patients; the scale derived from the original Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms, but with the attention and alogia sections removed. Reference Reichman, Coyne, Amirneni, Molino and Egan1 The difference in effect sizes and significance between the negative items of the PANSS, the PANSS negative subscale and the SANS-AD may indeed reflect the different behaviours assessed. Replication of this work with a larger dementia sample would thus be valuable to fully explore these initial findings, in particular using instruments specifically developed for individuals with neurodegenerative diseases, Reference Robert, Clairet, Benoit, Koutaich, Bertogliati and Tible39 while also accounting for cultural factors. Reference Yi, Tan, Hong and Yu40 Future work should also include mechanistic studies to validate the proline x dopamine interaction hypothesis.

In summary, our exploratory, but positive finding that high proline has opposing effects on negative symptoms by COMT genotype in patients with dementia, further supports the development of therapeutics to specifically target the interaction pathway, across neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10926

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (C.L.C.), upon reasonable request, and approval by the Columbia Institutional Review Board.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study coordinators and clinical staff of Columbia University’s Taub Institute and Alzheimer’s and Dementia Research Center, as well as Taub’s recruitment coordinators Bettina Idney and Lambrini Whitney. Most importantly, we would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study, as well as their caregivers.

Author contributions

Concept and design of the study – C.L.C., J.D.C. Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data – J.D.C., H.W.C., A.M.C., J.H.A., B.R., S.A.W., N.K., E.D.H., L.S.H., D.P.D. and C.L.C. Statistical analysis – C.L.C. Drafting of the initial manuscript – C.L.C. Critical revision and review of the final manuscript – all authors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Department of Defense (DoD) via grant number W81XWH-18-1-0285 to C.L.C. and the National Institute of Aging (NIA) via grant number R21AG058020 to C.L.C. This publication was also supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through grant number UL1TR001873. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the DoD.

Declaration of interest

C.L.C. is an International Editor and Statistical Advisor for the British Journal of Psychiatry Open and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper. C.L.C. and J.D.C. are inventors of a patent that describes use of proline-modulators as a treatment for schizophrenia. The patent is owned by their respective institutions and C.L.C. and J.D.C. may benefit financially in the future if these patents are licensed. L.S.H. has received research funding from Abbvie, Acumen, Alector, Alnylam, Biogen, Bristol-Myer Squibb, Cognition, Eisai, EIP/Cervomed, Genentech/Roche, Janssen/Johnson & Johnson, Transposon, UCB and Vaccinex. L.S.H. has received consulting fees from Biogen, Corium, Eisai, Genentech/Roche, Medscape, New Amsterdam and Prevail/Eli Lilly. D.P.D. has received research funding from the NIA and Alzheimers Association and is a Scientific Adviser for GSK, Acadia and Eisai. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.