While it is well known that Israel’s current government coalition is the most right-wing in Israel’s history, the fact that the government’s politics reflect an ideological shift toward American conservatism is scarcely discussed (but see Reznik Reference Reznik2020; Sagiv Reference Sagiv2020; Segal and Greenspan Reference Segal and Greenspan2024). The most pronounced manifestation of this shift is the judicial overhaul this government promotes, which is based on and legitimized by American conservative ideas of a restrained and politically controlled judiciary. Additional examples, in very different domains, include the refusal to sign the 2011 Istanbul Convention, opposing governmental intervention in family matters, and promoting school vouchers based on “parents’ choice.” Such policies were absent from the Israeli Right’s politics in the past, and they reflect a turn toward American conservative ideology that parallels, at least partially, similar ideological shifts in countries like Hungary, Poland, and India.

Given that conservatism, and American conservatism in particular, was never present as a coherent political ideology in Israeli politics (Ben-Porat Reference Ben-Porat2005; Rynhold Reference Rynhold2002), what stands behind this ideological shift? More specifically, what explains the importation of conservative ideas from the United States to Israel? The prevailing literature on ideational importation commonly focuses on national efforts by another country (Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2002), the efforts of expert ideational entrepreneurs (Ban Reference Ban2016; Campbell Reference Campbell2004), global knowledge networks of think tanks (Stone Reference Stone2001), and transnational advocacy networks (TANs) (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). But none of these sources of ideational importation apply to the ideological transformation of Israel’s Right; in fact, foreign powers like the US and the European Union have criticized the proposed judicial overhaul, and experts and leading think tanks have directly opposed it. Thus, viewed from prevailing frameworks of ideational importation, the growing presence of American conservative ideas is puzzling.

We tackle this puzzle by relying on the diaspora politics literature, according to which diaspora actors can operate as transnational agents of normative change (e.g., Adamson Reference Adamson2016; Shain Reference Shain1999; Shain and Sherman Reference Shain and Sherman2001). Specifically, we argue that ideological change can be explained by diaspora–local cooperation (DLC) and develop the microfoundational mechanisms of this causal connection (Délano Alonso and Mylonas Reference Délano Alonso and Mylonas2017; Koinova and Karabegović Reference Koinova and Karabegović2019). Like other forms of transnational ideas-based networks, DLC reflects a reciprocal connection based on ideational cooperation and agreement rather than material interests. But as diaspora actors are defined as such by their national attachment (Abramson Reference Abramson2017; Adamson Reference Adamson, Lyons and Mandaville2012), DLC is based on both shared ideas and values and a shared (constructed) national identity. This unique bond not only enhances the political legitimacy of the involved actors, but also enables an ideational change whose geographical scope—a single country—is narrower than that of TANs or global think tank networks, yet is concurrently more intensive and multidimensional within this scope. Accordingly, DLC serves as the basis for an ideational change that can yield an ideological shift.

Based on this analytical framework, our empirical analysis demonstrates how the rise of American conservatism in the Israeli Right was produced through a DLC of Jewish American actors and local actors on the Israeli Right. We focus on three central but distinct domains—government, economy, and social moralities—that have witnessed ideological changes of different scopes. This case selection allows us to examine, through process tracing, both the general mechanisms linking DLC and ideological change and the conditions supporting a more pronounced ideological shift. We rely on a variety of qualitative data sources, including publications by conservative Israeli organizations, parliamentary records, media articles, and interviews.

The Ideological Shift of the Israeli Right toward American Conservatism

Following Sheri Berman (Reference Berman2006; Reference Berman, Béland and Cox2011) and Michael Freeden (Reference Freeden1996; Reference Freeden, Freeden, Sargent and Stears2013), we define ideology as a coherent set of ideas, beliefs, and values that provide unifying narratives for interpreting political reality and mobilizing collective action. Both argue that ideologies are dynamic and adaptable. Accordingly, ideological change occurs when ideologies are reinterpreted, revised, or replaced, leading to significant shifts in political discourse, practices, and policy preferences. This process is not linear or uniform, and involves struggles over the interpretation and prioritization of key concepts within a given ideological framework.

Freeden’s morphological approach suggests that ideologies are organized around core, adjacent, and peripheral concepts. Core concepts define an ideology’s essence (e.g., “liberty” for liberalism and “equality” for socialism), provide its foundation, distinguish it from other ideologies, and remain relatively stable over time. Adjacent concepts interact with core concepts and modify their meaning, shaping the interpretation of an ideology in different historical and cultural contexts (e.g., concepts like “democracy,” “human rights,” and “free markets” influencing the meaning of “liberty” in liberalism). Peripheral concepts are located at the outermost layer of an ideology and accordingly are more susceptible to change, often responding to short-term political, societal, and intellectual developments. They thereby shape how an ideology is practically applied in specific circumstances (e.g., “environmental sustainability” influences specific contemporary policy debates without altering the core of the liberal ideology).

According to these definitions, the changes that took place among Israel’s Right amount to an ideological change. While its core values—territorial maximalism and Jewish ethnonationalism—remained stable, it adopted elements from the repertoire of American conservatism, which were historically absent from its ideology. These new adjacent and peripheral concepts have accordingly reshaped the ideology of the Israeli Right as a whole. To account for this shift and its specific components, summarized in figure 1, we first briefly survey American conservatism and its core values and concepts. We then elaborate on the absence of conservative political values from the Israeli Right’s ideology in the past and on why their current adoption reflects an ideological shift.

Figure 1 The Ideological Change of the Israeli Right

Note: Concepts that have achieved the deepest ideological penetration in contemporary Israeli conservatism are underlined.

American conservatism was largely a reaction to the expansion of the federal government. George Nash ([Reference Nash1976] Reference Nash2006) specifies libertarianism, traditionalism, and anti-communism as the three intellectual streams that together created the American conservative movement. Given its multiple sources, American conservatism is hardly a homogeneous ideology (Kurth Reference Kurth, Levinson, Williams and Parker2016). On economic issues, American conservatism resists state intervention and promotes individual freedom and small government (Van Horn and Mirowski Reference Van Horn, Mirowski, Mirowski and Plehwe2015), supporting tax cuts, deregulation, privatization, anti-unionism, and climate skepticism (Dunlap and Jacques Reference Dunlap and Jacques2013).Footnote 1 On social issues, it adheres to “traditional Judeo-Christian values” and to social institutions like religion and family, viewing abortion as violating the natural moral order and the LGBTQ rights movement as undermining traditional family structures (Fisher Reference Fisher, Barclay, Bernstein and Marshall2009; Munson Reference Munson2010). On judicial issues, American conservatism emphasizes a restrained interpretation of the law, often adopting an “originalist” constitutional interpretation (Young Reference Young1993, 623–25). Conservatives also support limited intervention in the decisions of the elected branches of government, but concurrently suspect broad government powers and object to government “overreach” (Kalman Reference Kalman1998).

The rise of American conservative ideology in Israel has been pronounced since conservatism, as a holistic political ideology—especially in its American version—had never existed in the Israeli political landscape (Rynhold Reference Rynhold2002). As depicted in the left panel of figure 1, historically, the definitive attribute of the Israeli Right was its nationalist and hawkish stances and its embrace of ethnonationalism (Pedahzur Reference Pedahzur2001). The main party on the Israeli Right is Likud, whose predecessor, Herut, was primarily defined by its territorial maximalism. Especially since 1967, the Israeli Right has been defined by its opposition to territorial compromise and less so by socioeconomic issues. Even though Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has been identified as “neoconservative,” this mainly pertained to the unique combination of hawkishness and neoliberalism in his political stances (Ben-Porat Reference Ben-Porat2005), from which the moral and governmental-judicial aspects of American conservatism were completely absent.

Furthermore, the Israeli Right has traditionally promoted policies and positions that do not align with, and even run counter to, American conservatism. On economic issues, while Likud occupied positions on the right side of the political spectrum, it traditionally advocated for a robust welfare state. The religious parties in Israel traditionally even possessed a socialist overtone (e.g., Hominer Reference Hominer2016), and the ultra-Orthodox parties simply promoted sectarian interests (Gutwein Reference Gutwein2016).

On judicial and governmental issues, the Israeli Right was not committed to ideas of a restrained judiciary or a politically controlled bureaucracy. For example, Likud’s first coalition was well known for refraining from politicizing the civil service and its “pork barrel” politics of political appointments was motivated by pragmatic rather than ideological considerations (Galnoor Reference Galnoor2010, 117–18). Furthermore, members of the Knesset (MKs) from Likud and MafdalFootnote 2 voted for the 1992 legislative changes on which Israeli judicial activism was based. Likud’s chairman of the Knesset Constitution Committee, Uriel Lin, and Justice Minister Dan Meridor were the main proponents of these changes (Sapir Reference Sapir2010).

On moral and social issues, the Israeli Right possessed views that were rooted in Jewish religion and tradition rather than traditionalist tendencies. For example, opposition to same-sex marriage was not based on a discourse that highlighted family values, but rather derived from the sanctity of customary conceptions of marriage in the Jewish tradition and the perceived contradictions between Jewish law and gay relationships (Ben-Porat et al. Reference Ben-Porat, Filc, Ozturk and Ozzano2023).

As summarized in the right panel of figure 1, and detailed in the empirical analysis, the nascent Israeli conservative movement differs from the historical Israeli Right along all these three ideational axes. Regarding economic issues, the conservative Right’s support for market competition is grounded in moral arguments regarding individual rights and liberties and portraying progressive policies like affirmative action as unjust and immoral. Such arguments were generally absent from the historical Right’s discourse. On governmental issues, past criticism of the judicial system primarily pertained to content rather than structure—expressing frustration whenever the court made decisions that countered their political goals (e.g., regarding illegal settlements in the Occupied Territories) and portraying the judges as “leftists,” without anchoring such frustration in principled demands to curtail judicial powers. In contrast, the ascending conservative Right wishes to politicize the courts by, among other measures, enhancing political control over judicial appointments. On social issues, the conservative Right has “secularized” traditional religious arguments against LGBTQ and nontraditional families, using American conservative themes such as “family values.”

Indeed, and as further elaborated in the empirical analysis, the degree of ideological change has varied across different ideational domains. It has been most pronounced in the governmental domain, in which American conservatism has become a defining feature of the contemporary ideology of the Right, as reflected in its public discourse and its sweeping reform attempts. In the economic and moral domains, new ideological components have entered the discourse and affected certain policies, though in a less sweeping manner.

In sum, the ideological shift we identify and analyze below does not entail a wholesale replacement of the ideological structure of the Israeli Right, but a reconfiguration of its morphology. Specifically, the Israeli Right discarded a range of adjacent and peripheral concepts previously integral to its ideological formation, such as the welfare economy and civil rights. Concurrently, it preserves its core concepts: territorial maximalism and Jewish ethnonationalism. The shift thereby reflects a rearticulation of ideological boundaries rather than a rupture, consistent with Freeden’s understanding of how ideologies evolve through the recomposition of their internal conceptual architecture.

The Puzzle of American Conservatism in Israel

The question that then follows is what explains the process through which elements of American conservative ideology have been entering into the Israeli Right after years of absence. According to Sheri Berman (Reference Berman2006; Reference Berman, Béland and Cox2011), ideological changes result from a combination of structural conditions and human agency. Specifically, her model of ideological change defines a two-stage process through which old ideologies decline and new ones emerge. First, an existing ideological framework erodes, often due to political crises, social transformations, or economic upheavals. As an ideology fails to address contemporary challenges, its credibility diminishes, its dominant ideological assumptions are questioned, and a political space opens for new interpretations and solutions. In the second stage, new ideological alternatives emerge and compete, based on the efforts of actors who formulate, promote, and institutionalize alternative ideological streams. These streams compete for dominance, and those best addressing contemporary political and social dilemmas ultimately gain traction. This process is not deterministic but depends on whether ideological entrepreneurs—politicians, intellectuals, and activists—manage to articulate compelling narratives and build coalitions that can institutionalize the new ideology.

Berman’s model is compelling but only partially applies to our case, especially since the Israeli Right’s core ideology did not go through crisis. While the Oslo process somewhat challenged territorial maximalism, the collapse of the process has significantly weakened its “dovish” ideological rival (Yakter and Tessler Reference Yakter and Tessler2023). Nevertheless, the weakening of the “two-state solution” within Israeli politics did challenge the Israeli Right since it led to a shift in the center-left political agenda toward socioeconomic issues (most prominently following the 2011 social justice protests across Israel) and judicial issues (culminating in the judicial allegations against Netanyahu, the Right’s unquestionable leader). While these shifts did not undermine the core tenets of the Right’s ideology, they exposed its relative weakness vis-à-vis its political opposition. They allowed the Center-Left to challenge right-wing dominance thanks to the progressive positions of the Israeli public on socioeconomic issues (Yakter Reference Yakter2020) and the high popularity of anti-corruption discourse (Shain Reference Shain2010).

Yet beyond these contextual conditions, which pertain to the first stage in Berman’s model and enabled the ideological shift within Israel’s Right, the question that remains pertains to the second stage: what explains the particular direction of its ideological shift toward American conservatism? Specifically, as this shift was based on the importation of ideas foreign to Israeli politics, which actors stood behind this importation and what explains their success? As we elaborate below, given the prevailing literature on ideational importation, this is a puzzle. The actors the literature commonly identifies with ideational importation—resourceful governments, prominent experts, and transnational advocacy bodies and networks—were either absent from the process or otherwise opposed it. Newly formed think tanks did play a role, but this does not solve the puzzle of who formed them, how they were formed, and why. The following paragraphs briefly elaborate on each of these sources of ideational importation and on their limited ability to account for the ideological shift in the Israeli Right.

One source of ideational importation identified in the literature is the efforts made by countries like the US to disseminate capitalist ideas during the Cold War (e.g., Dezalay and Garth Reference Dezalay and Garth2002), or those made by European countries to disseminate liberal values (Schimmelfennig Reference Schimmelfennig2001). Such efforts are supported by the disseminating countries’ vast economic and organizational resources. But the entrance of American conservative ideas into Israel was not supported by other countries. In fact, regarding the judicial overhaul, US and EU leaders expressed significant concerns about Israeli democracy (Bassist Reference Bassist2023; Friedman Reference Friedman2023).

An additional source of ideational importation the literature commonly refers to is experts. There are many examples of experts importing ideas (e.g., Lerner, Pereira, and Schlager Reference Lerner, Pereira and Schlager2024), especially when operating as ideational entrepreneurs (Mandelkern and Shalev Reference Mandelkern and Shalev2010) or within an “epistemic community” (Adler and Haas Reference Adler and Haas1992). Experts’ location at the intersection of two or more political arenas familiarizes them with both external ideas and the local arena they strive to influence (Campbell Reference Campbell2004). In addition, they can utilize their status and connections within international professional networks to enhance their local ideational influence (Ban Reference Ban2016; Mandelkern and Shalev Reference Mandelkern and Shalev2010). But experts also cannot be regarded as the source of American conservatism in Israel. Most Israeli experts—economists, political scientists, and legal scholars—have fiercely warned against the judicial overhaul and its detrimental effects on Israel’s economy and democracy (e.g., Ater, Raz, and Spitzer Reference Ater, Raz and Spitzer2023; Roznai and Cohen Reference Roznai and Cohen2023). Indeed, some actors who took part in disseminating conservative ideas in Israel had professional credentials. But their marginal position within their field suggests that their expertise cannot be regarded as sufficient for inducing a comprehensive ideational change.

Two additional sources of external ideas discussed in the literature are transnational networks of think tanks and TANs. Though these two types of networks are markedly different, both are characterized by a nonhierarchical structure that enables actors to operate beyond their domestic context, and provides the means by which organizations—individually and in coalition—can project their ideas across countries.

TANs are well-recognized agents of change, particularly in regard to high-value-content issues marked by informational uncertainty: human rights, environmental protection, and Indigenous rights (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). These networks consist of international and domestic nongovernmental organizations, social movements, foundations, and even parts of governmental institutions. They function across national borders to promote change in international politics through the strategic mobilization of information and ideas. While TANs are commonly identified with the liberal international order, there are also transnational networks of organizations that promote right-wing and conservative values (Bob Reference Bob2012) and therefore can potentially explain a conservative ideological shift. Yet in our case, there were no apparent TANs in action.

Like TANs, transnational networks of think tanks have been key actors in advancing various ideas. Think tanks operate as a repository for ideas produced elsewhere and advocate for their application to a local context, building a domestic network and linking it to a global one, and providing expert opinions (Stone Reference Stone2001). Whereas TANs are commonly identified with liberal values, transnational networks of think tanks are also identified with conservative ideas and values, such as economic neoliberalism (Fischer and Plehwe Reference Fischer, Plehwe, Salas-Porras and Murray2017) and climate change skepticism (Dunlap and Jacques Reference Dunlap and Jacques2013). Unlike the above-mentioned agents of ideational change, think tanks’ role in importing American conservatism to Israel is more complicated. Established Israeli think tanks either did not play a role in promoting conservative ideology or explicitly opposed it. Yet newly formed think tanks have played a crucial part in the change we seek to explain (Segal and Greenspan Reference Segal and Greenspan2024). But as we elaborate below, the latter were not part of a global network of think tanks and reflect a different “origin story.” Who stands behind the formation of these think tanks, and how did they manage to induce an ideological change in the Israeli Right?

Theoretical Framework: Cooperation of Diaspora and Local Actors as an Additional Channel of Ideational Importation

We explain the rise of American conservatism in Israel by building on prevailing insights from the diaspora politics literature, focusing on DLC—the cooperation of diaspora and local actors—as an additional channel of ideational importation. Like the above-mentioned sources of ideational importation, DLC is based on shared ideas and/or values. Yet it differs from them by being also based on national identity. The sense of national kinship serves as the impetus for DLC, whose raison d’être is exerting influence on the homeland, rather than a universal diffusion of a certain set of ideas or values. This means that DLC fosters a unique type of political legitimacy for the involved transnational actors and provides an infrastructure for multidimensional ideational importation, through which ideas within a variety of domains are being imported and thereby can culminate in an ideological shift.

Relying on and combining insights from prevailing literatures on diaspora politics and on global think tank networks and TANs, our framework elaborates on the microfoundations of DLC as a source of ideological change. First, it discusses DLC as a source of ideological entrepreneurship and the motivation of diaspora and local actors to cooperate for the sake of ideological change. Second, it highlights how specific characteristics of DLC, and the contextual conditions it operates within, affect its ability to induce this change.

DLC as a Source of Ideational Importation

We regard a “diaspora” as a socially and politically constructed identity rather than a fixed entity (Adamson Reference Adamson, Lyons and Mandaville2012; Brubaker Reference Brubaker2005; Ragazzi Reference Ragazzi2012; but see Grossman Reference Grossman2019). Diaspora actors are defined as such by their self-perception—and by the perception of their local collaborators—as stakeholders in their homeland politics. DLC does not reflect the cooperation of a whole diaspora with the whole nation-state. Diaspora communities consist of diverse individuals, groups, and organizations that often hold divergent, and possibly conflicting, political positions (Grossman, Böcü, and Baser Reference Grossman, Böcü and Baser2025; Shain [Reference Shain1989] Reference Shain2010). Thus, like other sources of ideational importation (e.g., TANs), DLC reflects cooperation at the individual or organizational level between diaspora actors and local actors who share specific values and beliefs.

In contrast to TANs or epistemic communities, DLC is based not only on shared ideas and values, but also on a sense of national kinship in which shared ideological commitments are embedded. An extensive literature details how diasporas influence politics within their nation-states (Lyons and Mandaville Reference Lyons and Mandaville2012) by providing financial support and economic investments (e.g., Leblang Reference Leblang2010; Reference Leblang2017), promoting their homeland interests through lobbying efforts in their hostlands (Shain Reference Shain1999), and assisting in—or perpetuating—homeland armed conflicts (Shain Reference Shain2002; Smith and Stares Reference Smith and Stares2007). Diasporas also take part in identity formation processes within their homeland (Abramson Reference Abramson2017; Shain and Sherman Reference Shain and Sherman2001). These examples reflect that diaspora actors have a stake—first and foremost, in their own eyes—in domestic politics and a sense of belonging to the national community. Given this self-perception, diaspora actors may seek to promote ideological change they consider normatively desirable or politically appropriate in their homeland.

The sense of national kinship also affects how diaspora actors are defined and regarded in the homeland, and the unique type of political legitimacy they enjoy. Although located “geographically outside the state,” they are still seen “identity-wise […] inside the people” (Shain and Barth Reference Shain and Barth2003, 451).Footnote 3 Thus, diaspora actors cannot be easily dismissed as “outsiders” meddling in internal issues. This is particularly true for local political actors who hold an anti-universalist political approach and regard transnational influences as illegitimate interventions. Beyond such a mutual view of kinship, local actors are inclined to take part in such cooperation when they can utilize the resources that diaspora actors offer them. In the context of ideational importation, these resources are not only material but also ideational. Following Berman (Reference Berman, Béland and Cox2011), we suggest that local actors will cooperate with diaspora actors in ideological importation especially when they see a necessity to utilize outside ideas to update their ideology in response to changing social and political realities—for example, when they suffer (or perceive themselves as suffering) from an ideational weakness vis-à-vis their political rivals and when they can utilize “imported” ideas as new sources of political power.

Conditions Supporting DLC-Induced Ideological Shift

DLC shares various features with other forms of transnational ideational networks like global think tank networks and TANs (Adamson Reference Adamson, Al-Ali and Koser2003). First, DLC-induced ideational importation relies on the localization of outside ideas. This pertains not only to linguistic translation but also to contextual adaptation, whereby through “congruence building” (Acharya Reference Acharya2004), translation (Ban Reference Ban2016), or “vernacularization” (Levitt and Merry Reference Levitt and Merry2009), external perceptions, ideas, norms, and values tap into local issues and offer concrete responses and solutions to prevailing concerns. Localized ideas may vary in their content and scope, ranging from relatively wide scope or generality, like paradigms and worldviews, to more concrete and narrow ones, like specific policy ideas and programs (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). When ideational localization is effectively applied to ideas of various scopes, it can potentially affect more meaningfully adjacent and peripheral concepts, and thereby yield an ideological shift. In other words, effective ideational localization is a necessary condition for ideological change. But as we elaborate below, it is not a sufficient condition; effective ideational localization does not automatically translate into ideological change.

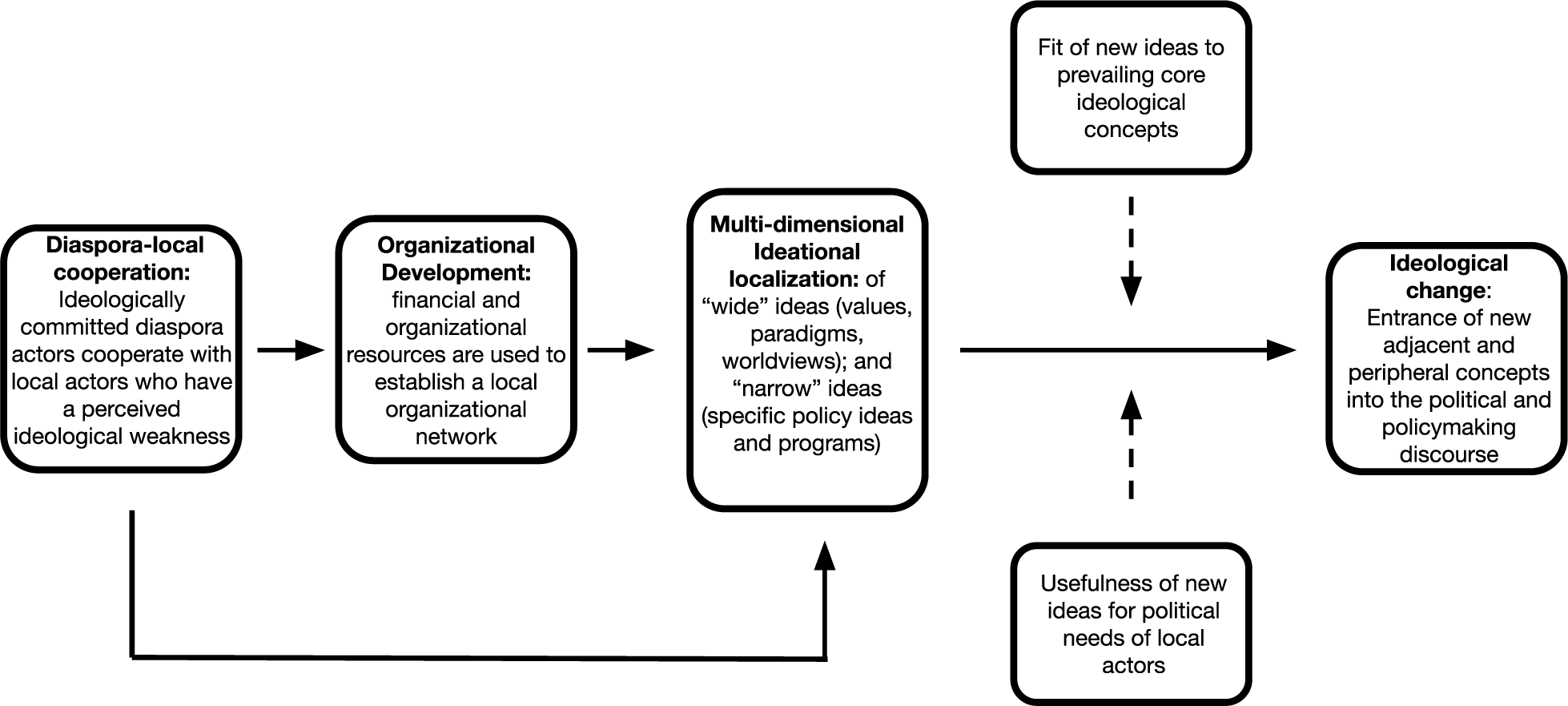

Second, and as depicted in figure 2, organizational development—namely the construction of organizations that serve as ideational dissemination platforms, including think tanks, media outlets, journals, and book publishers—is a necessary condition for effective ideational localization (Rich Reference Rich, Béland and Cox2011). Although diaspora actors do not enjoy the immense financial resources of states, some diaspora communities (particularly in the US) possess relatively significant financial resources they can mobilize.

Figure 2 Causal Links between DLC and Ideological Change

Third, DLC organizational structure also reflects reciprocal and horizontal relations between a variety of individual actors. Such relations are primarily based on shared ideational commitments rather than material interests. Both organizational development and ideational localization require the cooperation and division of labor between diaspora and local actors. Diaspora actors are crucial for providing material resources for organizational development, but local actors are needed to utilize these resources in establishing an organizational infrastructure. Regarding ideational localization, local actors, who are much more familiar with local ideas and discourse, are crucial for the active adaptation of external ideas to local systems of meaning, but it is diaspora actors who provide local actors with initial access to these ideas (Adamson Reference Adamson2006).

But DLC also differs from prevailing forms of transnational ideational networks. Whereas the basis for cooperation in other transnational ideational networks is primarily joint ideational commitments, DLC is primarily based on a (constructed) sense of national kinship and a shared national identity. This crucial difference affects the type of ideational importation DLC is involved in. Prevailing forms of transnational ideational networks focus on relatively specific ideas, norms, or issues. This definitely applies to TANs, which usually focus on concrete issues like human rights or environmental protection, but also to global think tank networks, which cooperate on a shared commitment to a certain agenda (Abelson Reference Abelson1995; Dunlap and Jacques Reference Dunlap and Jacques2013; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998). Such a focus only makes sense, since the common ideational and/or normative agenda defines the reason for the formation of these networks in the first place.

We argue that since it is primarily based on national kinship, DLC provides an infrastructure for multidimensional ideational importation. That is, an importation of ideas that relate to various themes and are not focused on specific issues or domains (in contrast to the importation of neoliberal economic ideas that relate to a specific domain, for example). While multidimensional ideational importation may result from other types of cooperation, we suggest that by being based on a sense of national attachment, DLC is a sufficient condition for such ideational importation.

We further suggest that multidimensional ideational importation is a necessary but insufficient condition for facilitating an ideological change like the one we seek to explain. Since multidimensional ideational importation is not limited to a specific domain, it will not necessarily yield an ideological change whose scope and depth are equal across all its domains. Thus, even when ideational importation relies on effective organizational and ideational localization, the transformation of prevailing ideological concepts depends on certain conditions. First, following Berman, who asserts that ideological change occurs in response to concrete crises or opportunities that render new ideas useful, we suggest that the uptake of new ideas is contingent upon their perceived necessity given shifting historical or political circumstances. Specifically, the ideological effect of imported ideas depends on whether and how they serve the interests of political actors in the specific political context they operate. For example, different imported ideas may have differing utility in terms of coalition building, neutralizing political threats, or legitimizing certain policies or political actions.

Second, following Freeden, we suggest that imported ideas affect adjacent and peripheral ideological concepts when they align with, and reinforce, core ideological concepts. When proposed ideological changes reinforce core ideological components, they are more likely to be embraced and adapted and to become a definitive ideological tenet. Conversely, when imported ideas conflict with or require significant reinterpretation of core components, ideological change will be more limited. Of course, such “fit” between imported ideas and prevailing concepts is not predetermined; rather, it is open to an active interpretation of both imported ideas and prevailing concepts, and to political contestation over such interpretation. Nevertheless, the adoption of some interpretations will be easier than others when they rely on preexisting political tendencies.

In sum, and as summarized in figure 2, our framework suggests that DLC contributes to organizational infrastructure development through which multidimensional ideational localization can take place. We further suggest that multidimensional ideational localization is a necessary but insufficient condition for ideological change, which also depends on whether and to what degree imported ideas align with core ideological concepts and concrete political needs.

Research Design

We utilize the suggested analytical framework for studying the Israeli Right’s ideological shift toward American conservatism. We focus on the three central domains within American conservative ideology: government, economy, and social moralities. Focusing on these domains allows us to examine whether and how the suggested causal mechanism applies to the influence of core American conservative concepts on the Israeli Right’s ideology. Furthermore, since the depth of ideological change in these three domains is not identical and has been most pronounced in the governmental domain, comparing them allows us to examine the conditions affecting the actual impact of localized ideas on the prevailing ideology.

We use process tracing (Beach and Pedersen Reference Beach and Pedersen2016; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2012) to examine the causal links between DLC and ideological change. Table 1 elaborates on possible observable manifestations and relevant data sources for each of the links of the causal mechanism and details the type of evidence that each observable manifestation provides; specifically, whether it passes a “hoop” test (necessary evidence for validating our argument, whose absence undermines the argument and whose presence does not confirm the argument), a “smoking gun” test (sufficient evidence for validating our argument, whose absence does not reject the argument), or a “straw in the wind” test (indicative but inconclusive supporting evidence) (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2012).

Table 1 Observable Manifestations of the Causal Mechanism, Process-Tracing Tests, and Data Sources

As detailed in the right-hand column in table 1, various data resources were used, chosen according to the evidence required for examining each causal link. Note that since the link between DLC and organizational development is not formally reported, it was examined through six semistructured interviews with prominent figures in Israeli conservative organizations who took a central and active part in DLC and in forming the main organizations embodying organizational development.Footnote 4 These interviews, which took place in 2021 and lasted 30–90 minutes, were conducted in person and via Zoom videoconferencing software by Or Asher, who also transcribed them. Interviews were conducted in Hebrew, and excerpts from them and from other Hebrew sources were translated by the authors. The timing of these interviews, well before the political turmoil in which these organizations have been involved since late 2022, enhances their reliability and provides a unique source of information.

DLC-Led Organizational Infrastructure for Multidimensional Ideational Domains

The following paragraphs examine the role of DLC in building the extensive organizational infrastructure on which the multidimensional ideational localization of American conservatism took place. To do so, we first describe the main organizations that have carried out this task, and then assess how DLC has played out in this process.

Extensive Organizational Development

The two main new conservative organizations in Israel are Tikvah Fund and Kohelet Policy Forum.Footnote 5 Both were founded and funded by Jewish American philanthropists associated with the American conservative movement. Tikvah was founded in the US in 1992 by Zalman Bernstein, a Jewish American financier dedicated to propagating conservative ideology and Orthodox Jewish views among American Jewry (Cohen Reference Cohen2017). Initially, Tikvah’s main activity in Israel was supporting the Shalem Center, a conservative think tank that was formed in 1994 and later turned into an academic institute, but in 2016 Tikvah established an Israeli branch to supplement its American one. Tikvah’s chairman since 1999, Roger Hertog, is a renowned conservative philanthropist. In addition to Tikvah’s resources, Hertog’s own foundation contributes to conservative think tanks and educational programs in American universities. In 2024, Tikvah’s Israeli branch was renamed the Herut (“liberty”) Center.

Tikvah funds several projects in Israel, including the journal HaShiloach, which circulates right-wing and conservative ideas; Shibolet, a publishing house for contemporary nonfiction books that aims to appeal to “an elite in construction” and to further “the intellectual revolution of the conservative right-wing” (Shibolet, n.d.); the Israel Law and Liberty Forum (ILLF), a legal organization modeled after the Federalist Society; the Argaman Institute, which hosts student seminars on conservative thought; and Iyun, a journal targeted at the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Israel. Until 2018, Tikvah also funded Mida, a conservative online media outlet that presents hawkish and nationalist stances on foreign policy matters, libertarian positions on economic issues, and skeptical positions on climate change. Tikvah’s overarching effort is “to cultivate a conservative elite that would carry these ideas to every walk of life—media, bureaucracy, judiciary, and academia” (Tikvah Fund 2020).

The second main organization, Kohelet Policy Forum, is a policy-oriented think tank engaged mainly in policy research, lobbying, and petitioning Israeli courts. Kohelet was founded in 2012 by Moshe Koppel, an American-born Israeli and a professor of computer science at Bar-Ilan University. The identities of Kohelet’s benefactors have not been officially disclosed, but media reports trace two Jewish American philanthropists—Jeffrey Yass and Arthur Dantchik—as its main funders (Slyomovics Reference Slyomovics2021). Yass and Dantchik are also major donors to conservative and libertarian organizations in the US like the Cato Institute, the Atlas Network, and the Institute for Justice (Jones Reference Jones2021).

DLC Initiates Extensive Organizational Development

Interviews with key figures in Tikvah and Kohelet provide “smoking gun” evidence supporting the suggested causal link between DLC and organizational development.Footnote 6 First, they reveal that conservative American Jews and their Israeli partners met and discussed possibilities for cooperation after the former had reached out to, or actively searched for, Israelis who could build and head local organizations. These initial contacts were followed by extensive funding provided for this goal by diaspora actors. For example, Tikvah’s Israeli branch was initiated in a New York Tikvah seminar, where Hertog and Eric Cohen, the then executive director of Tikvah, met with Amiad Cohen, who would become the executive director of Tikvah’s Israel branch. Hertog and Eric Cohen were looking for someone with management skills who identified with the fund’s ideas to set up and operate the fund’s Israeli branch. Likewise, Mida was founded following a meeting between Ran Baratz—who lectured in several Tikvah-related organizations such as Shalem—and Hertog. Hertog initiated the meeting after Baratz received media attention for not being hired by the Hebrew University, allegedly due to his political opinions. Kohelet was founded following a series of meetings between Moshe Koppel and Kohelet’s funders, who revealed their shared interest in affecting public policy in Israel.

As suggested above, DLC is also based on local actors who perceive their position as weak vis-à-vis the rival political camp, thereby seeking new ideas to challenge their opponents. This was a prevailing sentiment among right-wing activists and intellectuals in Israel since the 1990s (e.g., Hazony Reference Hazony2016), especially on issues beyond foreign affairs and security. A recurring assertion in the interviews was that the Israeli Right lacked a coherent agenda on social issues. According to one interviewee, “[the Right was in a] vacuum … from the early 1990s and most prominently in national experiences like the Gaza disengagement to the 2011 social protests.” This vacuum, the interviewee continued, is long standing in Israeli politics: “[T]he Right was traditionally defined by security concerns and issues of religion-state relations, while other issues were neglected or absent. [It] failed to recognize the significance of the Ka’adan ruling in time, nor did it grasp the importance of the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty when it was enacted. The Right had no grounding in these areas. […] Gradually, as the Left pushed harder, people on the Right began recognizing this void and engaging with it.”Footnote 7

In this context, American conservatism provided an overarching ideology for these underlying tendencies. As stated by an interviewee who participated in Tikvah’s seminars in the US and was part of Israeli conservative organizations, “[s]ome of the content was new to me, but … it aligned well with my intuitions. It was a different language and set of emphases. This exposure helped me understand the wider conversation, see my place in it, and engage with perspectives I hadn’t understood before—creating a common ground for dialogue, especially with left-wing viewpoints.”Footnote 8

The Role of National Kinship

Crucially, this different language was embedded in the context of shared national attachment. The links between diaspora and local actors were based not only on shared ideas and ideological perceptions but also on a kinship perception. As we suggested above, this affects the political legitimacy of the involved actors, which in the Israeli case is manifested most clearly in the differential treatment of donations from foreign governments and diaspora actors. For instance, new Likud-led legislation proposes to impose an 80% tax on all donations originating from foreign governments and bar organizations whose primary funding sources are foreign states from submitting petitions to the Israeli Supreme Court. The targets are liberal and human rights organizations, which unlike right-wing organizations rely on such donations (Shpigel and Lis Reference Shpigel and Lis2025). Against that, the political legitimacy of diaspora actors is reflected by the fact that Israeli organizations across the political spectrum—both right- and left-wing—seek their financial support. For example, the reservist organization “Brothers in Arms,” established in opposition to the judicial overhaul, conducted multiple fundraising events in the US (Tibon Reference Tibon2023).

National kinship is also crucial for understanding the motivation of involved diaspora actors. The most prominent demonstration of this is Hertog, Tikvah’s emeritus chairman. Though he does not necessarily frame his philanthropic efforts in nationalist or Zionist terms, his actions and investments clearly articulate a profound connection to the Jewish people and Israel. Hertog agreed to lead Tikvah at the request of his late business partner Zalman Bernstein, who established the Avi Chai Foundation (1984) and later Tikvah to stimulate Jewish intellectuals in Israel and the US (Stephens Reference Stephens2010). Speaking at the first conference of the Israeli conservative movement, Hertog (Reference Hertog2019) emphasized that commitment to the survival and prosperity of Israel is not merely symbolic but calls for active participation in its political and institutional development.

As we suggested above, such national attachment is a precondition for a willingness to invest in multidimensional ideational change, one that is not limited to a particular ideational domain. Indeed, Hertog (Reference Hertog2019) explicitly expressed his willingness to promote political conservatism in Israel, assuming that “ideas must manifest themselves in the cultural and political processes” to shape the country’s future. The role of national attachment is also demonstrated by the variety of enterprises promoted by Hertog, through Tikvah and personally, already during the 1990s. These include $100 million contributed by Tikvah for the Shalem Center. Moreover, Tikvah, under Hertog, contributed to Israeli universities and educational institutions like Ein-Prat ($2 million), a premilitary leadership academy for high-school graduates located in a West Bank settlement. Hertog also personally contributed $250,000 in 2016 to the Ir David (“City of David”) Foundation, a Jerusalem-based settler organization focusing on archaeological excavations and real-estate acquisitions.

The diaspora actors who funded Kohelet are more clandestine in their philanthropic endeavors in Israel, so evidence for their national attachment less explicit. Yet in several interviews Moshe Koppel described them as “very Jewish” and “Zionists.” Describing his initial meetings with them, which were meant to be about business cooperation, he attested that Israel and “how to make it better” were more interesting subjects for them to discuss (Rotenberg Reference Rotenberg2019). Furthermore, the observable choices of these Jewish American philanthropists offer compelling evidence of their national attachment to Israel. For example, Yass and Dantchik contributed to Israeli organizations like the Israeli national emergency service, Magen David Adom (e.g., $150,000 in 2019), as well as to PEF Israel Endowment Funds ($200,000 in 2016), a charity that collects and distributes money to charities in Israel only.

The national attachment of involved diaspora actors is further underscored by the fact that Hertog, Yass, and Dantchik also direct their contributions to organizations exclusively in the two countries to which they have national identification, Israel and the US. This includes prominent conservative US think tanks like the Cato Institute and the American Enterprise Institute; Yass and Hertog were also board members in these respective organizations. Hertog also contributes to Jewish organizations like Chabad chapters in American universities. Their targeted investments reveal a prioritization of Jewish and Israeli causes. They reflect how these diaspora actors perceive themselves not merely as ethnic or religious affiliates, but also as active participants in the Israeli national project, with both a stake and a role in shaping its future.

Ideological efforts might also dovetail with economic interests, since these philanthropists are also financial investors in Israel (for instance, Yass and Dantchik have invested in the Israeli fintech company eToro, where Likud MK Nir Barkat’s investment firm BRM is also a major shareholder). Their support for conservative causes aligns with policy preferences that fit their business agendas. In this sense, the promotion of conservative economic and social policies—like deregulation, tax reductions, or opposition to labor protections—can simultaneously serve ideological and material goals.

Empirical Analysis: From Organizational Development to Ideational Localization and Ideological Change

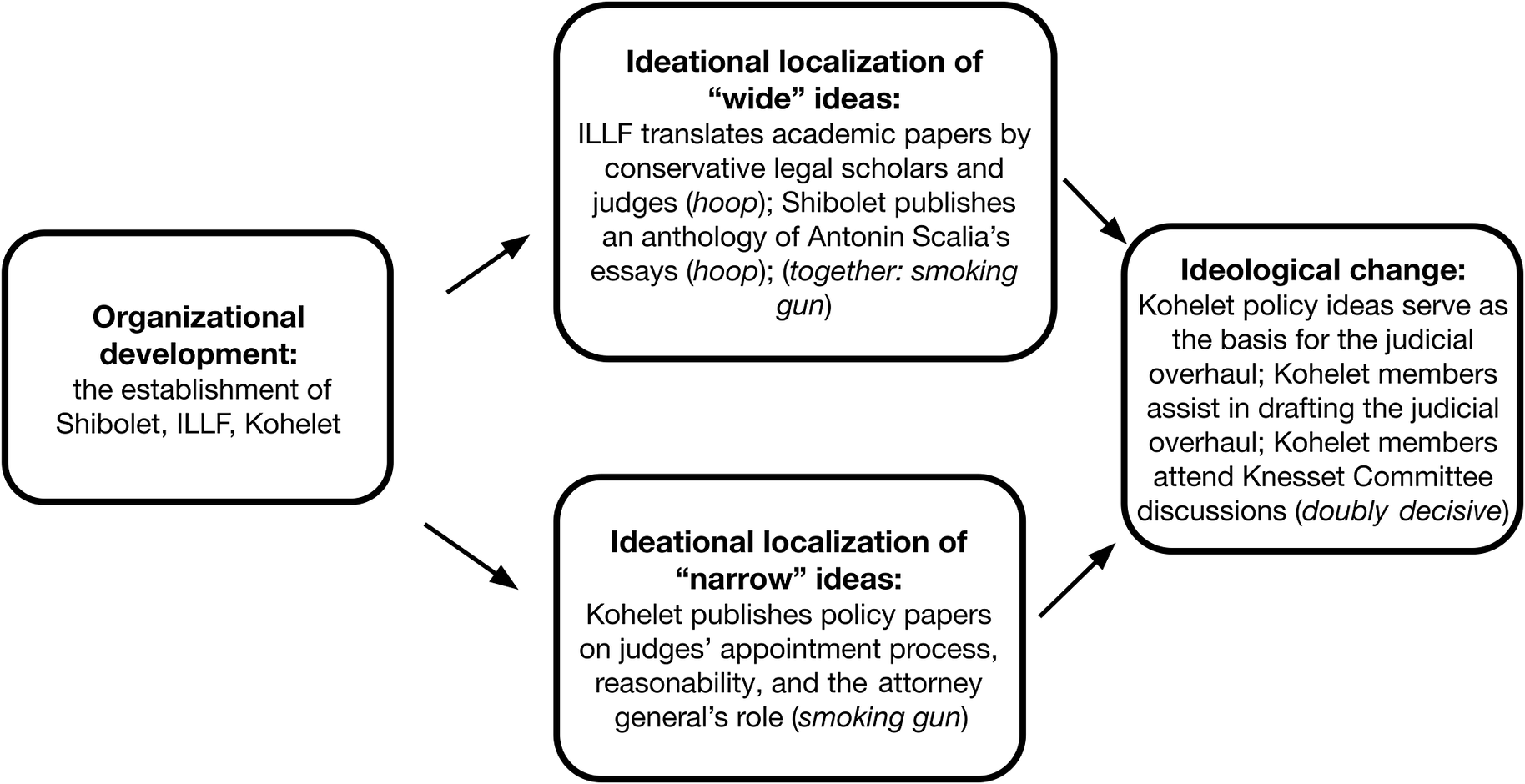

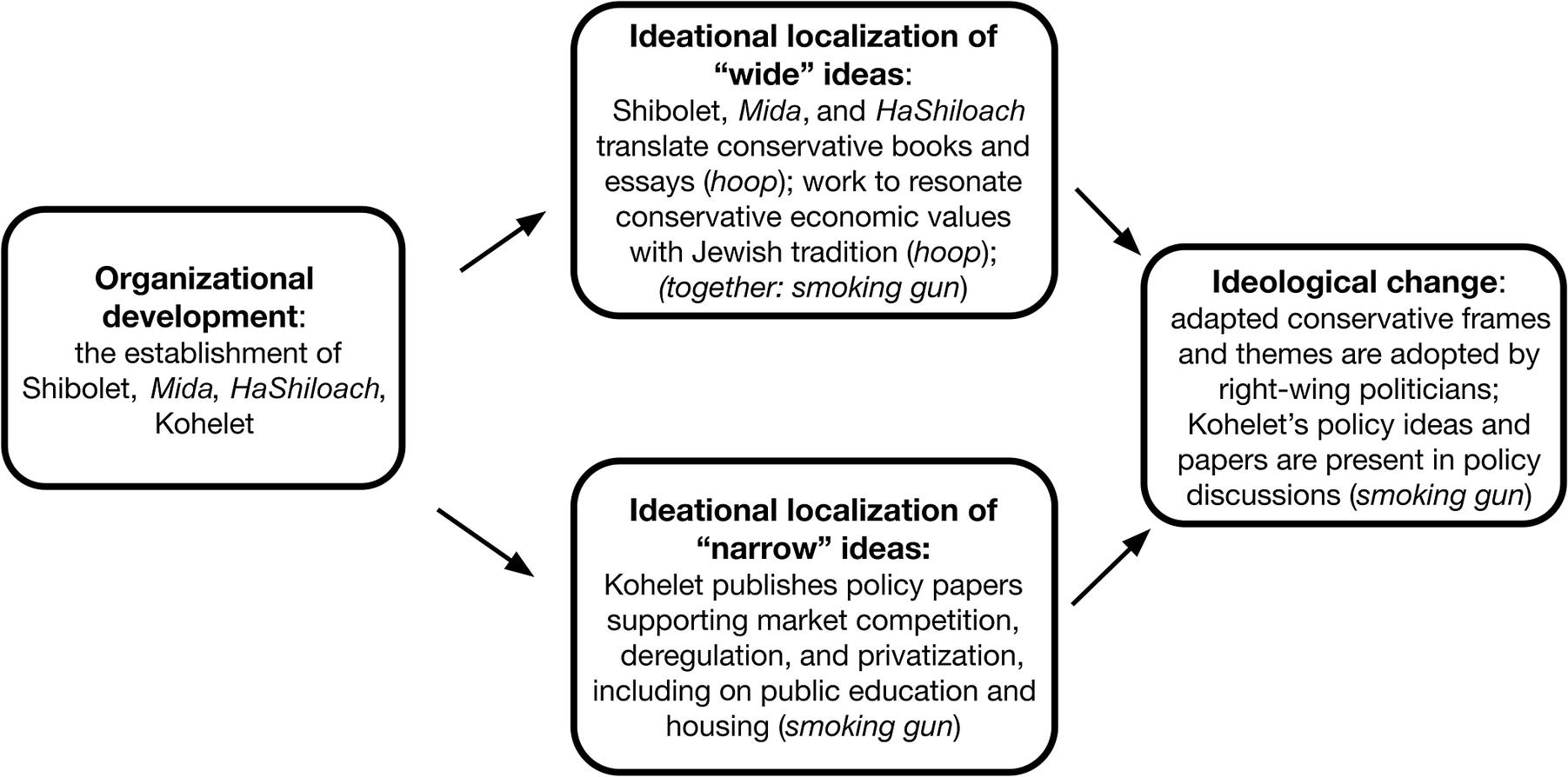

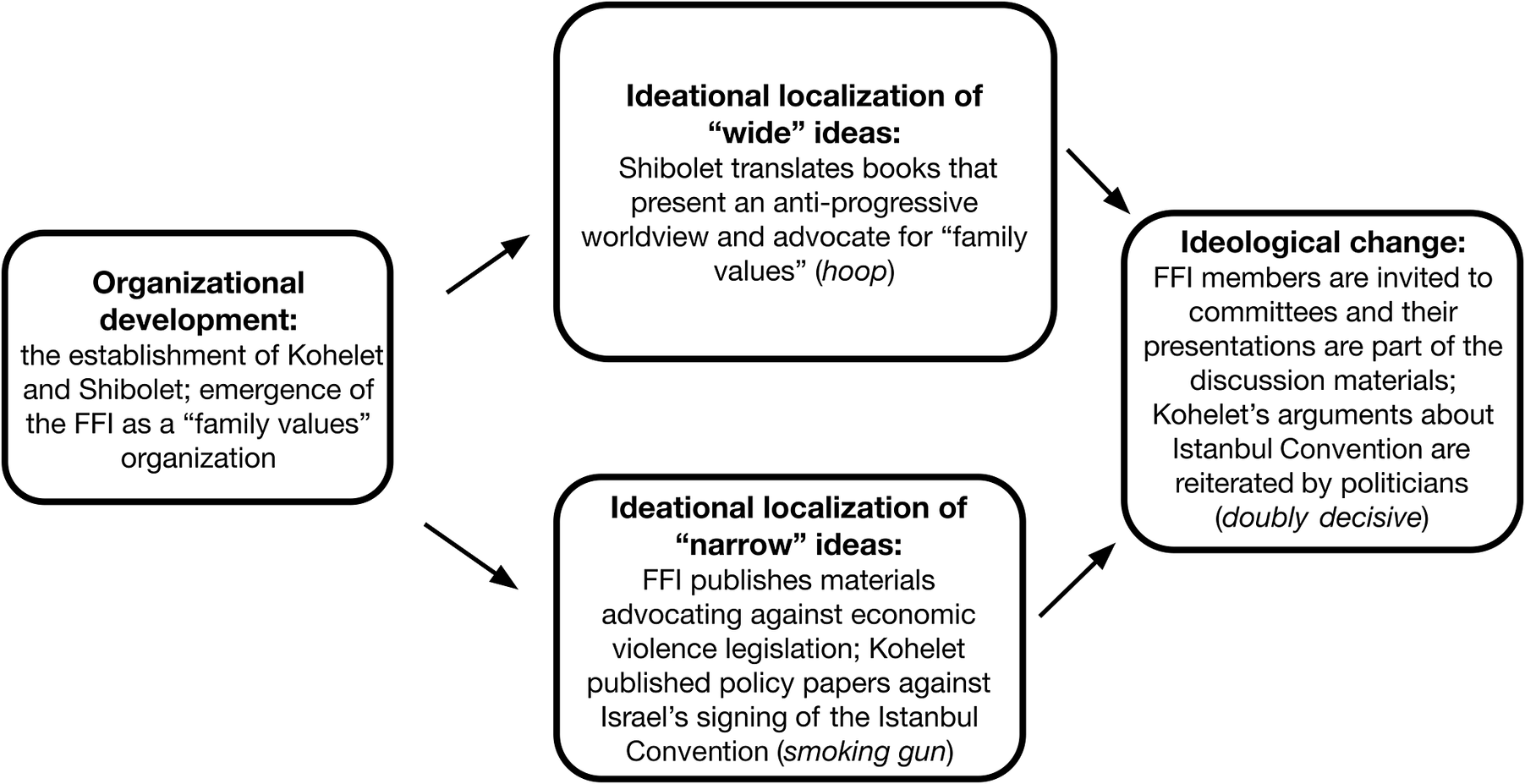

The following sections describe how organizational development—forming a local network of conservative organizations—enabled ideational localization—the adaptation of American conservative ideas into the Israeli context. They also describe how ideational localization evolved into an ideological change within the Israeli Right—namely, the entrance of conservative ideas into the political discourse and into policies promoted by right-wing political parties and politicians. The empirical analysis from here onward is organized under the three above-mentioned domains: government, economy, and social moralities. Figures 3, 4 and 5 summarize the main causal links between organizational development and ideological change in each of the themes. These figures also detail the type of process-tracing tests the empirical evidence passes (see the online appendix for a detailed assessment of the empirical evidence).

Figure 3 Causal Links between Organizational Development and Ideological Change (Government)

Figure 4 Causal Links between Organizational Development and Ideological Change (Economy)

Government

The central organization spreading a conservative legal approach in Israel is ILLF, the Federalist Society emulator established in 2020 by Tikvah Fund (see figure 3). ILLF translates articles authored by conservative legal scholars into Hebrew and curates for them an online library. Ideational localization in this context is most clearly manifested in the library’s dedicated section for criticizing Israel’s “constitutional revolution,” which granted the courts judicial review authority between 1992 and 1995. Notable translated articles, all uploaded during 2022, include former US Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s “A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law,” Jeremy Waldron’s “The Core of the Case against Judicial Review,” and “Judicial Activism Reconsidered” by Thomas Sowell. ILLF’s online library aims to introduce principles of judicial conservatism to Israeli law students and legal practitioners and to provide foundational resources for developing institutional reforms in Israel, particularly regarding the role and authority of the Supreme Court (ILLF, n.d.).

While conservative Israeli organizations endorse principles like those supported by American conservatives, they adapt them to Israel, which unlike the US lacks a fully written constitution. This is most evident in Shibolet’s comprehensive anthology of translated texts by Justice Scalia, published in 2023 amid a fierce national struggle around the Israeli government‘s attempt to weaken the judiciary. Notably, each chapter was accompanied by a short introduction, clarifying its relevance to Israel, despite the distinctions between the two legal systems. For instance, regarding Scalia’s support for the political appointment of justices, it was emphasized that adopting such an approach in Israel would allow the people, rather than the judges themselves, to control the judicial nomination process (Scalia Reference Scalia, Nataf and Nataf2023, 179).

Kohelet also plays a crucial role in the localization of policy ideas pertaining to governmental issues. The goal, according to Koppel, is “the dissolution of unelected power hubs that exploit the state’s power to impose their own values” (Tikvah Fund 2020). This pertains to the professional ranks of the Israeli bureaucracy and, more crucially, to judges. As per American conservatism, Kohelet papers argue that unelected institutions like the Supreme Court ought to be weakened vis-à-vis the legislative branch. Accordingly, one Kohelet paper provides a comparative analysis of judicial appointment processes in 42 democracies and 50 US states, arguing that the process in Israel, in which legislators supposedly play a limited role, is unusual (Cohen, Bakshi, and Nataf Reference Cohen, Bakshi and Nataf2021). This paper suggests politicizing the judges’ appointment process by ensuring a majority for the government within the Supreme Court. Another Kohelet paper utilizes the conservative worldview in the context of the attorney general, who is traditionally an independent unelected official. The paper argues for subordinating the attorney general to government ministers and for defining the attorney general’s legal opinions as advisory instead of binding (Bakshi Reference Bakshi2016). An additional Kohelet paper criticizes the judicial activism of the Israeli Supreme Court, contending that the court expanded the meaning of the “reasonableness” measure to intervene in executive decisions and arguing against such a move (Solo and Garber Reference Solo and Garber2022).

Kohelet’s policy papers in the governmental domain also address the public sector, which in line with American conservative thought is perceived as a liberal stronghold. This perspective is also demonstrated by Ran Baratz (Reference Baratz2020), founder of Mida, who asserted in an article in HaShiloach that “every senior official, in Israel as in any administration in the Western world, undergoes a sharp political indoctrination, which clothes Progressiveness in the guise of ‘expertise,’ ‘professionalism,’ and ‘objectivity.’” In line with this view, Kohelet advocates for increasing political appointments within the Israeli public sector, which due to its British tradition is much less politicized than its US counterpart (Ben-Shlomo and Klein Reference Ben-Shlomo and Klein2015).

The very significant impact of these ideas on ideological change is most clearly manifested in the judicial overhaul, advanced by an Israeli government composed solely of right-wing parties, since January 2023. The reform’s key components closely align with proposals previously articulated in Kohelet’s policy papers: limiting the Supreme Court’s authority to exercise judicial review, revoking the court’s power to review basic laws, abolishing the reasonableness standard in the judicial review of administrative actions, reforming the judges’ appointment committee to grant government control over judicial appointments, and diminishing the legal authority of government and ministerial legal advisors by changing their advice from binding to nonbinding (Roznai, Dixon, and Landau Reference Roznai, Dixon and Landau2023, 295–96).

Kohelet played a key role in formulating the judicial overhaul. Aviad Bakshi, author of several of the above-mentioned papers and head of Kohelet’s legal department, openly acknowledged that he counseled Justice Minister Yariv Levin in drafting reform bills. Levin met with Bakshi six times between January and March 2023, twice right before the reform was announced. Levin also held meetings with Kohelet’s Moshe Koppel in January and February and expressed gratitude to Bakshi and Kohelet when announcing the reform (Pyuterkovsky Reference Pyuterkovsky2023). Shimon Nataf, a former Kohelet researcher whose papers served as blueprints for Levin’s reforms, became a special advisor to MK Simcha Rothman, the Knesset Constitution Committee chairman and a staunch advocate of the reforms (Chilai Reference Chilai2023). Kohelet also took an active role in the Knesset Constitution, Law and Justice Committee discussions about clauses of the judicial overhaul.

Furthermore, prominent figures within Israeli conservative organizations championed the judicial overhaul through both American and Israeli media outlets. Prior to the official announcement of the reform by Levin, two executive members of ILLF and Tikvah Fund authored an article in the National Review arguing for the necessity and urgency of a judicial reform, strikingly resembling the actual reform components (Meisel-Diament and Green Reference Meisel-Diament and Green2022). In an interview with a right-wing Jewish American outlet, Koppel asserted that the reform is necessary since “the checks and balances that exist in other [Western, democratic] countries do not exist in Israel,” and therefore, “The [Supreme] Court can do whatever it wants” (Isaac Reference Isaac2023).

Local conservative organizations have also managed to shift the public discourse regarding the judicial system in Israel. A tangible manifestation of this shift is the now customary differentiation—promoted by right-wing actors—between “conservative” and “liberal” judges, a distinction that was virtually nonexistent in Israeli discourse until recently (Rothman Reference Rothman2018). The origin of this American-style ideological framing can be traced to the tenure of Ayelet Shaked, a prominent politician from the right-wing Jewish Home party, who served as justice minister from 2015 to 2018, and who explicitly sought to reshape the judiciary along ideological lines. This distinction became even more prominent during the judicial overhaul initiative led by the Right, which was explicitly framed as a “conservative” reform (Baum Reference Baum2016). The significance of this discursive shift lies in its power to recast the critique directed at the judicial system by the Right not as an antidemocratic move, but as a legitimate ideological confrontation between competing worldviews.

Economy

The harbinger of conservative economic thought in the Israeli Right is Shalem, which in 1995 established a publishing house dedicated to translating canonical conservative works to Hebrew (e.g., Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom and Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom). Continuing Shalem’s effort, the primary actor today responsible for translating American conservative economic worldview is Shibolet Library, a collaborative initiative of Tikvah and a right-wing publisher, Sela-Me’ir. Prominent examples include Thomas Sowell’s The Quest for Cosmic Justice, Mark Levine’s Unfreedom of the Press, and Charles Murray’s Losing Ground, the “budget-cutter’s bible” (New York Times 1985). Concurrently, Mida, the right-wing media outlet funded by Tikvah, translates economic articles and essays from American conservative outlets like the National Review (e.g., Krauthammer Reference Krauthammer2022; Sowell Reference Sowell2022) and prominent conservative figures like Dennis Prager. Figure 4 traces the causal links between these groups and ideological change in the economic domain.

Localizing and promoting conservative economic thought that adheres to free-market ideas is not an easy task given Israel’s interventionist background. To overcome this difficulty, conservative ideational localization has been based on reaching back to Jewish tradition and scriptures. Conservative localizers depict the Jewish tradition as one of self-reliance and adherence to limited government (Hazony Reference Hazony2016; Sorek Reference Sorek2020). For example, the chief editor of HaShiloach, Yoav Sorek (Reference Sorek2017), contends that biblical social commandments advocate for the social responsibility of the affluent rather than distributive justice, and that the Bible sees wealth and “growing the pie” as desirable even if inequality expands. Another prominent local conservative figure, Rabbi Chaim Navon (Reference Navon2021), argues in a book published with Tikvah’s assistance that the Bible’s disdain for the king’s authority suggests that Jewish tradition adheres to a limited government that does not intervene in individual and community autonomy.

Ideational localization of conservative ideas also encompassed concrete policy ideas and programs. Formulating policy proposals advocating market competition is mainly done by Kohelet, which advocates deregulation, tax cuts, and privatization of public services and utilities. Kohelet also advocates anti-union measures like introducing a “right to work” clause that allows employees to abstain from union membership (Feder, Sarel, and Zicherman Reference Feder, Sarel and Zicherman2016).

The formulation of specific policy recommendations grounded in conservative economic principles is particularly discernible in the education field, where a recurring theme is the imperative to decentralize and privatize the Israeli public education system. In line with its general anti-union stance, Kohelet’s policy papers also call for transitioning teachers’ employment arrangements from collective agreements to performance-based individual contracts (Ben-Shlomo Reference Ben-Shlomo2018; Lubowitz Reference Lubowitz2018; Shafet, Ben-Shlomo, and Klein Reference Shafet, Ben-Shlomo and Klein2018; Tomer Reference Tomer2021). Kohelet also promotes a voucher system, incorporating “school choice” and “parents’ choice” frames from analogous American organizations (DeBray-Pelot, Lubienski, and Scott Reference DeBray-Pelot, Lubienski and Scott2007). Interestingly, in the field of education, a “second generation” of organizational development took place: organizations founded through DLC paved the way for the expansion of a local network of conservative organizations. With Kohelet’s financial support, Kohelet-affiliated researchers established two organizations advocating for the privatization of Israel’s education system and the weakening of the powerful teachers’ unions: The Next Generation: Parents for Choice in Education, and Teachers Lead Change. These two groups are precedents of other organizations that promote such causes in the name of parents and teachers.

The visible impact of localized conservative economic worldviews is manifested in their adoption by right-wing politicians who incorporate conservative frames and themes into their agenda. Furthermore, these politicians contribute to the dissemination of conservative economic ideas within the Israeli political landscape and the broader public sphere. For example, Shaked (Reference Shaked2017) published an article in Tikvah’s HaShiloach unfolding a conservative worldview that sees any vote in the Knesset as “a vote of no confidence in our ability as individuals and communities to conduct ourselves well enough without the state determining the course of our lives.” Crucially, to establish her viewpoint Shaked cites works published by Shalem’s library of political theory translations, including those written by John Locke, the American Founding Fathers, and Milton Friedman.

The contribution of ideational localization to ideological change is no less clear when it comes to specific policy ideas. Upon reviewing Knesset committee discussions, it is evident that Kohelet is frequently invited to committees addressing various economic issues. In the following analysis we focus on the presence of Kohelet’s policy ideas regarding public education, illustrating how ideas, once localized, enter the political and public debate.

As mentioned above, Kohelet’s vision for the Israeli public education system is one of privatization and school choice. Following their publication in 2018, these policy ideas appeared in discussions of the Knesset Education Committee. In a 2020 discussion on schools’ administrative autonomy, a Kohelet researcher explained that a lack of administrative autonomy for school principals contributed to the unequal achievements of Israeli pupils. Moreover, committee members were presented with a position paper of an umbrella organization called the Coalition for Autonomy in Education, of which Kohelet is a member, which argued for a transition from collective agreements to individual contracts for teachers. The paper also suggested implementing a voucher system, using the “school choice” trope used by conservative American groups (Coalition for Autonomy in Education, n.d.). These suggestions were reiterated in the discussion by a Likud MK (Knesset 2020b, 3–4). Notably, the proposal for school choice was included in the platform of the Religious Zionist Party in 2022 (Religious Zionist Party 2022). Though we do not have evidence that the Religious Zionist Party was directly influenced by Kohelet’s working papers, the similarities between its ideas and those of Kohelet are significant. In addition, Kohelet has influenced the policies promoted by the Religious Zionist Party in other policy areas (e.g., regarding the judicial system, which we detailed above).

Beyond education, Kohelet actively promotes a broad range of policies grounded in conservative economic principles. These include efforts to reduce the role of the state in various sectors and to advance market-based reforms. For instance, the organization has published policy papers advocating for the abolition of Israel’s public housing system, arguing that it distorts the housing market and creates inefficiencies. Similarly, Kohelet has called for the privatization of Israel’s public broadcasting services, claiming that they impose an unnecessary burden on taxpayers. Notably, a recent bill introduced by Israel’s minister of communications appears to be directly influenced by these proposals.

Social Moralities

Analogous to the dynamics observed in the previous subsections, Shibolet translates into Hebrew conservative works like Ben Shapiro’s The Right Side of History and Bullies, Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life, and Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe. (While Murray and Peterson are not Americans, their works have granted them a stature within American conservatism that allows us to include them in our analysis.) These books counter the liberal standpoint regarding social issues, expressing a Manichean perspective that demarcates a clear divide between postmodern and progressive ideologies (e.g., feminism) and conservatism. The former are portrayed as posing an existential threat to collective identities like the nation, the community, and the family. A common theme lies in these books’ contentions against identity politics, which they regard as fostering societal divisions.

A particularly prominent topic is the family. In 2022, Shibolet translated Scott Yenor’s controversial book The Recovery of Family Life (translated into Hebrew as To Save the Family), which claims that liberalism, feminism, and the sexual liberation movement are a “rolling revolution” that will eventually abolish marriage and family (Schaefer Riley Reference Schaefer Riley2021). Drawn from this type of argumentation, Israeli conservatives localize concerns about marriage and family. In HaShiloach, there is a dedicated section called “family and community,” whose articles generally argue that the family cell is under attack by progressive and postmodern approaches embedded in state institutions and academia (Navon Reference Navon2017; Pua Reference Pua2021). Similarly, Rabbi Navon’s book (2021), financed also by Tikvah, argues that postmodernism is a “dismantling ideology” that undermines the importance of family and sees it as an oppressive institution.

The influence of social-moral conservative ideas on the Israeli Right is evident in the emergence of “family values” organizations (see figure 5). While closely associated with Republican and conservative politics in the US, this issue has hardly been politicized in Israel, which is widely regarded as the epitome of family-centric values among postindustrial societies (Fogiel-Bijaoui Reference Fogiel-Bijaoui, Roopnarine and Gielen2005). The most prominent manifestation of the localization of policy ideas is the work done by the Family Forum Israel (FFI), a coalition of organizations advocating for conservative family policies and against family policies they identify as progressive. FFI’s objective is “preserving and promoting” the family cell in Israel and protecting it from feminist, progressive, and LGBT agendas that they believe wish to dismantle it (FFI, n.d.). Like the organizations that focus on education policy, FFI reflects second-generation organizational development: prominent members of FFI have participated in Kohelet’s training seminars, and several organizations operating within FFI benefit from Kohelet’s financial support (Glazer Reference Glazer2021).

Figure 5 Causal Links between Organizational Development and Ideological Change (Social Moralities)

As in the context of economic and governmental ideas, local conservative organizations are actively engaged in decision-making processes. For example, FFI members appeared before the Knesset Constitution Committee in September 2020 to object to legislation aimed at defining financial violence within familial relationships as a criminal offense, thereby enabling spouses, primarily women, to file charges in such cases (Knesset 2020a). They asserted that such legislation would allow state institutions to intervene in the sanctity of the family cell, potentially undermining the institution of marriage and, consequently, reducing marriage rates and contributing to lower birth rates and national demographic decline. To support this argument, the presentation cited the translation of Douglas Murray’s The Strange Death of Europe.

The ideological change can be observed in right-wing politicians’ adoption of the same “family values” tropes. MKs who opposed the financial violence bill, mostly from right-wing parties, framed their opposition in line with FFI’s argument. These MKs based their opposition on a mix of noninterventionist and moral arguments, arguing that state institutions—in this case, courts—should not infiltrate the family and that family sanctity rests on intricate personal relationships that must not be disrupted by any outside intervention. During the discussion, an MK from a religious Zionist party pejoratively stated that the bill derived from “progressive forces” that seek to dismantle the Israeli family. Another MK from Likud even claimed that such bills possess a “communist dimension” (Knesset 2020a, 18, 24).

Another illustrative example of ideational influence and change in the context of family policy is conservative organizations’ opposition to Israel’s accession to the Istanbul Convention, a human rights treaty established by the Council of Europe to address violence against women and domestic violence. Initially, the Israeli government indicated its willingness to sign the treaty in November 2021. Yet once conservative organizations “discovered” this initiative they actively sought to thwart it, and they eventually succeeded by gaining broad support from right-wing politicians. In May 2022, Kohelet promptly published several position papers asserting that the Istanbul Convention is not effective in combating violence against women and poses a threat to Israel’s immigration policy (Peter and Bakshi Reference Peter and Bakshi2022). One contention posited that the convention would subject Israel’s public systems to intrusive oversight by the EU (Kontorovich Reference Kontorovich2022). These arguments were reiterated by right-wing MKs in a conference titled “The Curse from Istanbul” and hosted by MK Simcha Rothman (Baruch Reference Baruch2022). Rothman argued that “joining the Istanbul Convention will not decrease violence against women but will jeopardize Israel’s immigration policy, exploiting the crucial issue of domestic violence to introduce the Council of Europe and foreign organizations into the education and legal systems in Israel.” A Likud MK contended that the treaty would permit “anti-Zionist and anti-Semitic human rights organizations to infiltrate schools and undermine Israel from within,” while another claimed that it would “facilitate the entry of millions of Muslims into Israel” (Baruch Reference Baruch2022).

Kohelet and other conservative organizations were invited to a Knesset committee discussion addressing the issue in May 2022. Their papers served as materials for the committee’s discussion, during which they articulated their primary arguments against endorsing the treaty, which were very similar to those expressed in Rothman’s conference. Ultimately, the coalition agreement between Likud and the Religious Zionist Party stipulated that Israel would not join the convention (Knesset 2022, 19–21).

We should note that there is a fundamental difference between the conservative approach and how family values were perceived by the “historical” Israeli Right. Indeed, family values are not a new theme in the Israeli Right, especially among its religious political parties. Yet such discourse was primarily rooted in Jewish law, emphasizing, for example, the sanctity of customary understandings of marriage in the Jewish tradition and the perceived contradictions between Jewish law and LGBT relationships. In contrast, imported conservative ideas have introduced a “secularized” and ideologically rigid framing of family values. This ideological shift has reframed family values not solely as a religious concern, but as part of a broader ideological battle against progressive norms, akin to the framing used by American social conservatives. One consequence of this transformation is the emergence of principled right-wing opposition to policies aimed at combating domestic violence—policies that, in earlier religious discourse, would not have been seen as controversial. This suggests that the “secularization” of family values has paradoxically produced more inflexible and ideologically driven resistance to certain social policy interventions.

Conditions Affecting Ideological Change

The empirical analysis of all ideational domains demonstrates the mechanism through which DLC has led to ideological change in the Israeli Right. Since these ideational domains reflect the core ideological tenets of American conservatism, the analysis supports our general claim regarding the role of DLC as a source of multidimensional ideational importation upon which an ideological shift is constructed.

At the same time, the empirical analysis also demonstrates that these three domains reflect varying degrees of ideological change. Ideological change has been most pronounced in the governmental domain. This is demonstrated by the overwhelming commitment of the current government to the judicial overhaul, which is combined with an extensive discursive change that legitimizes this institutional change. At the same time, ideological change in the economy and social morality domains remains limited to date. As suggested in the theoretical framework section, this variation can be explained by political needs and the degree of congruence between new ideas and the core ideological components. These two factors indeed differed between the three ideational domains.

The reform package in the governmental domain reflects the long-standing preferences of many right-wing political actors, who have viewed the judiciary—particularly the Supreme Court—as an impediment to their political and ideological agenda, especially in terms of furthering the settlement project in the West Bank. These long-term political aspirations combine with immediate political needs that ushered in the adoption of conservative judicial thought and the curtailing of the judiciary, namely the personal legal challenges facing Netanyahu and other members of his coalition (e.g., Aryeh Deri, the leader of the Shas party, a major coalition partner).

At the same time, these ideas align with core ideological components of the Israeli Right, particularly the rising tensions between the liberal-judicial framework and the evolving political reality in the Occupied Territories. Right-initiated expansions of formal legislation that entrench legal and civil discrimination between Israeli (Jewish) settlers and Palestinians have—based on the Right’s core values of territorial maximalism and Jewish ethnonationalism—increasingly clashed with the normative expectations of judicial liberalism. Similar tensions are evident within Israel, most notably in the case of the 2018 Nation-State Law, which, in line with the Right’s core value of Jewish ethnonationalism, prioritizes Jewish national identity while sidelining principles of civic equality. These confrontations mark a departure from traditional right-wing notions, which had often assumed that annexation of the Territories would eventually entail equal rights for the Palestinians. Contemporary right-wing ideology increasingly rejects this assumption, thereby deepening its conflict with the liberal-judicial order and supporting ideological realignment.

In comparison to the governmental domain, ideological change in the arenas of economic and social morality issues has been relatively limited. While there have been some achievements for the conservative agenda in the social-moral domain—such as the decision not to sign the Istanbul Convention and the refusal to advance domestic violence legislation—these accomplishments appear modest when compared to the significant ideological shifts in the governmental domain. In line with our framework, we suggest that the key reason for this disparity is that conservative ideas about social moralities do not provide opportunities to enhance the power or interests of right-wing political actors and only partially align with core components of right-wing ideology.