In the seventeenth century, Chinese literati initiated a philological movement that rejected the received traditions of imperial orthodoxy. Seeking to return to the ways of antiquity through textual criticism, these philologists described their approach using a phrase that originated in the first century: “Seeking Truth from Facts” (shishi qiushi 實事求是). Two centuries later, a middle-aged communist named Mao Zedong 毛泽东 (1893–1976) appropriated this phrase to encapsulate his approach towards revolutionary work, which privileged the first-hand investigation of local socioeconomic conditions. After Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping 邓小平 (1904–1997) argued that the success or failure of China’s nation-building program would depend in part on returning to the tradition of Seeking Truth from Facts, which, Deng argued, had been lost to the excesses of the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 1

In between these well-known episodes, shishi qiushi could be found in automobile advertisements, missionary translations, and on the gates of Confucian academies. For three hundred years, Chinese intellectuals have found the idea of Seeking Truth from Facts strangely alluring, employing shishi qiushi to capture something essential about themselves, their intellectual projects, and their moral commitments. But what is Seeking Truth from Facts? What explains its usage by such diverse personages, in such diverse contexts? What does the recurrence in the center of modern Chinese intellectual life of an epistemological phrase dating back two millennia tell us about modern Chinese history and the Chinese present?

Although Mao would likely have rejected a direct lineage linking him to Qing-Dynasty (1644–1911) philologists, since the 1980s Chinese historians have put forward Mao’s usage of Seeking Truth from Facts as evidence for Mao and the Communist Party of China (CPC) belonging to a trans-dynastic tradition of Chinese empiricism.Footnote 2 While such an interpretation results in part from the CPC’s increasing identification of itself with an invented and unbroken “traditional Chinese culture,” this also reflects an older historiographical tradition that emerged from the pens of liberal intellectuals such as Liang Qichao 梁啓超 (1873-1929), for whom the appropriation of shishi qiushi by eighteenth century philologists indicated the existence of a proto-scientific method in early modern China.Footnote 3 This idea—that even before Westernization, China was in some ways already “modern”—later found proponents amongst Anglophone scholars such as Joseph Needham, Benjamin Elman, and other China-centric historians who sought to demonstrate that imperial China possessed various characteristics associated with Western modernity, including science and capitalism.Footnote 4

When the works of Needham and Elman were first published, the excavation of China’s scientific history was a necessary corrective to the previously dominant historiographical paradigm of “Western impact,” which had overlooked important Chinese sites of natural inquiry and commercial growth.Footnote 5 However, this apologetic stance of reclaiming science, capitalism, and modernity for China was quickly attacked by other scholars who criticized the flattening of Chinese history and the erasing of differences between China and Europe.Footnote 6 In part, these debates arose from definitional differences. The apologetic framework frequently portrays science as a quality that one either “has” or does not, often broadening definitions so that it becomes difficult to establish what China truly shared with the West. Looking at the social context of Chinese empiricism allows us to explore new avenues of comparison with Europe. In this article, instead of defining science disciplinarily—such as the practice of astronomy or mathematics—I adopt a conceptual and social lens to explore how new ideas, methodologies, and organizational forms surrounding empiricism emerged in China around the same time as in Europe.

The genealogy of shishi qiushi paints a complex, nuanced picture. The rise of shishi qiushi provides additional evidence for a shared global empirical moment in the early modern period: stimulated by political collapse, the challenge of assimilating novel information, and new geopolitical shifts, global intellectuals questioned inherited textual traditions in favor of new empirical methodologies. This global empirical moment transformed the intellectual landscapes of China and Japan by playing midwife to the transposition of modern science to East Asia. As Lewis Bremner’s recent work demonstrates, Japanese intellectuals adopted science not only because of Western militarism and epistemic violence, but because East Asian scholars were interested in the natural laws of anatomy and optics.Footnote 7 China’s participation in this global empirical moment builds the case for East Asia sharing in an incipient global modernity.

However, there were also crucial differences between what empiricism meant in China and Europe. Tracing the path of shishi qiushi reveals that although since the seventeenth century Chinese and European knowledge communities faced parallel structural problems, they pursued different solutions. The rise of global empiricism was driven by the challenges faced by individuals and states in verifying and acting on novel, unfamiliar sources of information. However, while in Europe the solutions to this problem largely manifested in the form of state–society partnerships (often enmeshed within capitalist profit-seeking and inter-state competition), in China, these solutions largely emerged either exclusively in private scholarly circles or in state bureaucracies, with few productive links between the two.Footnote 8 Moreover, instead of engendering new organizational forms of knowledge production (such as professional associations), early modern China’s solutions to these problems largely relied on traditional literati circles or the imperial bureaucracy. Thus, although China was in some ways on a parallel track to Europe, it developed different orientations towards organizing knowledge production. We might then say that science and modernity in Europe and China ran along parallel, but not coterminous tracks.

Seeking Truth from Facts is perhaps the most prominent of the “epistemic virtues” of modern China. Shishi qiushi was a temporal parallel to European epistemic virtues such as “objectivity,” which guided European natural philosophers and, later, scientists. Although the idea of the “objective” (keguan 客觀) does exist in Chinese (a fin de siècle neologism from Japan), to be objective never described an aspirational moral stance in the way that Seeking Truth From Facts did. Comparing shishi qiushi to European epistemic ideals illuminates how Chinese empiricism differed from that of Europe. Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison argue that in Europe, epistemic virtues changed according to the “epistemic anxieties” engendered by shifts in understandings of the self.Footnote 9 In contrast, Chinese epistemic ideals have more closely followed shifts in the political and social realms. Whereas for nineteenth-century Western scientists, “objectivity” primarily described a relationship between humans and physical reality, Seeking Truth from Facts emphasizes the researcher’s connection to the social body, revealing how modern Chinese epistemology has always been reflexively concerned with the social position of knowledge production, and has understood knowledge production to be a collective social endeavor. Furthermore, compared to Europe, the epistemic anxieties of Chinese intellectuals were disproportionately centered on misinformation, fraud, and separating truth from falsity.

It is of course impossible to depict the entire history of Seeking Truth from Facts in a single essay. Instead, I depict three snapshots corresponding to the Qing Dynasty, the Republican Period (1911–1949), and the People’s Republic of China (PRC 1949–). Part one shows how during the Qing, shishi qiushi became associated with the quintessentially modern qualities of reflexivity, expertise, and syncretism.Footnote 10 Part two describes how in the Republican Period, after absorbing these qualities, shishi qiushi was popularized through newspapers, journals, and popular print. During this period, shisi qiushi became associated with Western science, but was also seen as fundamentally and retrospectively “Chinese” due to its ancient pedigree. These qualities led Mao Zedong to appropriate the phrase to describe his approach to revolutionary praxis. Part Three shows how after 1949 the CPC hoped that by encouraging cadres to “Seek Truth from Facts,” the state could eliminate misinformation and succeed in the data gathering required for Soviet-style planning. This was not an easy task, however, and statistical fabrication soon turned into an epidemic. After 1976, shishi qiushi became a rallying cry for Deng Xiaoping as he worked to reorient the CPC.

Part one: Qing origins

Early Qing empiricism: Philologists, textual skepticism, and reflexivity

In the early Qing, a philological movement emerged in which scholars questioned the authenticity of sacred texts foundational to state ideology. Carrying out what they called “evidential scholarship” (kaozheng 考證), these philologists argued that many passages and texts in the Neo-Confucian canon had been forged, and thus could not communicate the authentic teachings of Confucius and other sages. These philologists advocated reading texts from the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE–9 CE), seeking to rediscover a pure and uncorrupted dao, which they argued had been lost through generations of illegitimate transmission.Footnote 11

The Qing Dynasty was the most formative period in the history of shishi qiushi. Starting with evidentiary scholars, subsequent generations of Qing literati and officials would be similarly drawn to shishi qiushi’s empirical connotations. Over time, these actors imbued shishi qiushi with three important qualities: reflexivity, expertise, and syncretism. By the fall of the Qing, Seeking Truth from Facts would be deeply associated with the idea of knowledge as constantly progressing (reflexivity), the possession of specialized and practical knowledge that could be deployed to verify novel information (expertise), and with being both universal and Chinese (syncretism). Early Qing philologists were particularly instrumental in making reflexivity a Chinese epistemic virtue.

The seventeenth century rise of evidentiary scholarship, and philologists’ interest in textual forgery, was precipitated by a moral and intellectual crisis which accompanied the fall of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) to northeastern Manchu invaders. Even before the fall of the Ming, literati had begun to feel a sense of crisis, disillusioned with urban consumerism, the growth of sectarian cults, and political factionalism.Footnote 12 After the fall of the dynasty, Ming loyalists concluded that the dynastic failure was a result of Ming scholars’ indulgence in empty metaphysical thinking, exemplified by the figure of Wang Yangming 王陽明 (1472–1529). These scholars concluded that something had gone wrong in the understanding and practice of the dao, and they were determined to find what that was.

Evidentiary scholarship offered one potential answer. In the late Ming, philologically inclined scholars came to believe that portions of a number of important texts had been forged, including the Book of Documents. In the early Qing, scholars such as Yan Ruoqu 閻若璩 (1636–1704) continued this work, substantively proving the fabrication of key texts.Footnote 13 Evidentiary scholars slowly developed a theory of what had happened, arguing that Han-Dynasty literati had placed forgeries into academic circulation. In particular, evidentiary scholars condemned what were called “Old Text” (guwen 古文) manuscripts, which had reportedly been discovered in the walls of Confucius’ former residence, and whose script and literary style differed significantly from that of most contemporary Han texts, called “New Text” (jinwen 今文).Footnote 14 Some eighteenth-century evidentiary scholars began to advocate for returning to the study of New Text writings, such as the Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals, as opposed to the Old Text Zuo Commentary, which was seen as tainted.Footnote 15

Over time, China’s evidentiary scholarship broadened to include a range of philological techniques, including citations, tables and diagrams, chronologies, etymology, and calligraphic analysis.Footnote 16 Evidentiary scholars provided detailed and historically grounded commentaries, and also utilized novel sources, including collecting and transcribing bronze and stone inscriptions.Footnote 17 Philologists sought to recover not only forgeries, but ancient forms of ritual they believed had been corrupted, obscured, or forgotten, such as those related to ancestral rites and memorial halls.Footnote 18 Over time, Qing evidentiary scholars came to greatly value reflexivity as a virtue. This represented a sea change in how literati approach the classics, as philology “transformed Confucian inquiry from a quest for moral perfection to a programmatic search for empirically verifiable knowledge.”Footnote 19

For evidentiary scholars, Seeking Truth from Facts came to epitomize this reflexive approach to knowledge production. The phrase Seeking Truth from Facts originated in the History of the Former Han (Hanshu 漢書), the first century chronicle of the Western Han Dynasty compiled by Ban Gu 班固 (32–92 CE).Footnote 20 Ban Gu’s History includes a number of biographies of illustrious figures from the dynasty, including King Xian of Hejian 河間献王 (160–129 BCE), one of Emperor Jing’s thirteen sons. The brief biography begins:

King Xian of Hejian, [Liu] De, was established [as king] in the second year of Emperor Jing’s reign. He was a studious man who loved antiquity and sought truth in facts. He would obtain rare manuscripts from people, carefully copy them, return the transcription while keeping the original, and give handsome presents to encourage others to bring more. Because of this, learned people did not hesitate to come from afar to visit him, some bringing their ancestors’ old texts to offer to King Xian, so that his library came to rival that of the Han court.

河間獻王德以孝景前二年立, 修學好古, 實事求是。從民得善書, 必為好寫與之, 留其真, 加金帛賜以招之。繇是道術之人不遠千里, 或有先祖舊書, 多奉以奏獻王者, 故得書多, 與漢朝等。Footnote 21

The biography further noted that the texts King Xian coveted were not “superficial” (fubian 浮辯) like those collected by his relative, King An of Huainan, who wrote the eclectic Huainanzi (淮南子); rather, King Xian was noted to be passionate about classics such as the Rites of Zhou (Zhouguan 周官) and Book of Documents. Footnote 22

The original first century CE meaning of shishi qiushi should be understood in the context of Han letters. The Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) unified the warring states of the North China Plain in 221 BCE. Although short-lived, the Qin proved disastrous for scholarly life: not only did the first Qin emperor proscribe and destroy certain privately held texts, but when the Qin collapsed only fifteen years after its founding due to internal revolts, the sack of the capital led to many texts being burned and lost.Footnote 23 After the Han Dynasty replaced the Qin in 202 BCE, many manuscripts survived or were copied from memory, and found their way into imperially sponsored libraries. But this led to tricky questions surrounding the authenticity of recovered or orally transmitted texts.Footnote 24 Because shi 實 could approximately mean “authentic” or “verified,” it seems not unlikely that King Xian was involved in the verification of “authentic” texts and their links to antiquity.Footnote 25 This is supported by the fragmentary writings about King Xian, which describe him as compiling a Record of Music (Yueji 樂記) based on recovered sources, reconstructing and submitting ritual dances to the imperial throne, and endowing scholarly chairs for researching the Book of Songs and Zuo Commentary. Footnote 26

From this brief biography and other writings about King Xian, one can observe some of the reasons that Qing philologists might have admired him: he lived in the Former Han, their favored period; like them, he was a bibliophile, with an immense private library; he valued the classics above other works, and supported scholarly endeavors out of his own pocket. Additionally, the King of Hejian could be seen as embodying the kind of textual skepticism and reflexivity the philologists themselves had begun to practice.Footnote 27

Despite evidentiary scholars’ identification with the Han and their goal of restoring antiquity, evidentiary scholarship did not presage a return to the past as the philologists believed, but instead represented a revolutionary and reflexive approach to scholarship and intellectual life. In many ways, this movement was analogous to Renaissance Europe’s rediscovery of the Greek Classics, a point made early on by Liang Qichao, who called this period “China’s Renaissance.”Footnote 28 However, although China’s reflexive turn parallelled intellectual developments occurring in early modern Europe, the textual focus of evidentiary scholars meant that this break with the past was only partial. Although philological work was an important aspect of Renaissance scholarship, equally important was the flourishing of new forms of patronage for engineers such as Galileo, and a widespread cultural fascination with measurement and mechanical experimentation.Footnote 29 For Qing philologists, classical texts remained the arbiters of truth. Nor did the Qing court seek to develop and mobilize natural scientific knowledge on the same scale as in Europe. Outside of a limited use of Jesuit cartography and astronomy, the Manchus relied on innovations in frontier military strategy and logistics to build one of the largest land empires in history.Footnote 30 But even though the evidentiary scholarship movement did not alter the text-dominant nature of Chinese knowledge production, the long term impact of this skepticism was enormous: reflexivity did not remain localized within philology, but sprouted in other areas as well.

Ruling by natural law: Mid-Qing empirical statecraft

In the early 1800s, a similar empiricist bent developed amongst Qing officials, who increasingly shifted the focus of statecraft away from texts and towards political economy. This would have deep ramifications for the histories of Chinese intellectual life and governance, as subsequent generations of Chinese officials became interested in the empirical work of investigating and mobilizing “natural laws,” primarily in the social and economic realm.

By the late eighteenth century, philology had become part of mainstream gentry life in the Yangzi Delta, made possible by the renewed material and cultural flourishing of cities such as Suzhou, which had been devastated by the Manchu conquest. With governance and commerce restored, old gentry families and new money merchant-literati engaged in the printing of books, building of libraries, and discussion of textual authenticity.Footnote 31 Most of this commerce in books and ideas was largely divorced from the actual practice of government. Although philology may have initially been concerned with social issues, over time, it became a scholarly exercise.Footnote 32 However, great changes were simultaneously occurring in Qing bureaucratic culture that would slowly bring Seeking Truth from Facts into the orbit of Qing statecraft.

In the eighteenth century, a new breed of pragmatic official emerged who greatly esteemed the ethos of shishi qiushi. These bureaucrats were epitomized by the provincial governor Chen Hongmou 陳宏謀 (1696–1771). Born in the mountainous borderland of Guangxi Province, Chen grew up far from the Yangzi Delta, and arose as a bureaucratic prodigy not because of his literary style, but due to his moral rectitude and effective management of political economy. Chen’s broad intellectual mandate included knowledge of agriculture, land taxation, granary management, famine relief, dike maintenance, and military affairs. In his emphasis on broad, pragmatic erudition, Chen was heir to a branch of Confucian empiricism that rose to prominence around the same time as evidentiary scholarship. In the seventeenth century, Neo-Confucianism underwent a shift in focus towards worldly affairs and governance.Footnote 33 Stimulated by the increasingly complicated nature of Qing rule, these Statecraft officials concerned themselves with “reordering the world” (jingshi 經世), and sought empirical, specialized knowledge in the realm of government and political economy.

As a result of this shift, by the time Chen Hongmou rose to power, the language of shishi qiushi was already familiar to Statecraft officials. Growing up, Chen learned to describe his focus on worldly affairs as a “quest for substance and practicality” (qiushi 求實). According to William Rowe, shi 實 was possibly Chen’s “favorite adjective,” its meanings including “solid” and “real,” and also symbolizing the personality traits of “honesty, straightforwardness, frugality, and lack of pretense.” Chen opposed this solidity to falsity, emptiness, or flowery language. As Rowe writes, shi “referred to anything that was what it claimed to be—granaries that were genuinely filled (not merely reported as such), government workers who were actually on the job (not merely on the payroll),” whereas the opposite “existed in name only.”Footnote 34 The “substantive” was thus an orienting ideal in Chen’s professional and personal life: an official should focus on materially aiding the populace, and doing so with an earnest heart.

Although Chen and evidentiary scholars both shared a love of the “substantive,” Chen contrasted his shi against the “dry, unengaged pedantry” of philology.Footnote 35 Chen remained more committed to Neo-Confucian virtues than the philologists. For Chen, a dual focus on practical statecraft and moral cultivation were two sides of the same coin. Despite the association of shishi qiushi with evidential scholarship, Chen used the phrase to speak of this dual orientation. For instance, in an early-eighteenth century letter to the county magistrate Wang Wending 王文鼎 Chen wrote,

If [one] makes their primary concern materially aiding the populace, their heart will naturally be able to Seek Truth from Facts. [If so], material benefit will spontaneously arise, and maladies will spontaneously be removed. [Conversely], there is not a single pursuer of reputation or quick results who does not start out hardworking and end up idle.

苟以利濟為懷, 心必能實事求是。利不期興而自興, 弊不期除而自除。設沽名(或) [以] 求效, 未有不始勤而終怠者。Footnote 36

For Chen, merely being a technocrat was not enough: governance had to be carried out with an earnest and loving heart, and based in an official’s moral cultivation. Chen’s usage of shishi qiushi thus combined the two sides of “substantive” as both an orientation towards worldly action, and an earnest attitude. Having the correct attitude would lead the righteous official to seek out appropriate techniques of governance; earnestness would lead to empiricism.

Statecraft officials introduced a new permutation of reflexivity into shishi qiushi and Chinese empiricism. Philologists, Statecraft officials, and Chinese literati more broadly all agreed that universal “principles,” (li 理) fundamentally structured the universe. However, there was disagreement over exactly which “principles” to pay attention to, and where they were to be found. For Neo-Confucians such as Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200), li were most crucially innate moral principles that undergirded literati identity and ethical behavior, and acted as a foundation for familial and political stability.Footnote 37 For evidentiary scholars, the most important li were those that underlay the efficacy of ancient institutions and rituals, and were to be found in pre-Song texts.Footnote 38 But in the hands of Chen Hongmou and Statecraft officials, li began to resemble the “natural laws” of Enlightenment Europe.Footnote 39 For Statecraft officials like Chen, “principles” were to be found in natural objects and human affairs. These were not morally neutral laws; nor did they exist independent of government action. For Chen, the “natural” was also moral, and included the guiding role of officials and government. This led to a conflation in Chen’s mind between the moral and the politically efficacious. As Rowe describes, “Chen subjects his li to a sort of utilitarian test: what is right and moral will work in practice, and what truly works in practice must do so because it conforms to principle.”Footnote 40

This particular form of reflexivity would have long-lasting consequences. The conflation of natural law, morality, and efficacy, and their association with the epistemic ethos of shishi qiushi, would be inherited by Mao Zedong in the 1930s. Reflexive empiricism in the Qing Dynasty and in Communist China meant to evaluate the truth of an idea based on its governmental efficacy, and the people who were seen as rightly carrying out and evaluating truth were scholars-officials (and today, CPC cadres and leaders).

Late Qing bureaucracy: Expertise and the problem of verification

By the 1800s, shishi qiushi was used by evidentiary scholars and Statecraft officials to describe an ethos of earnest empiricism, a focus on worldly matters, and an appreciation of reflexivity. In the nineteenth century, shishi qiushi also came to be associated with verifying uncertain information, and was positioned as the opposite of falsity and fabrication.

Starting with Europe’s Age of Exploration, “verification” became a thorny problem for monarchs and merchants, as states and their subjects were flooded with novel information coming from Asia and the New World.Footnote 41 This information was “disembedded” from its immediate environment, sent through distant and increasingly impersonal social networks. European knowledge practitioners sought out new ways to cement social and epistemic trust, inventing various technologies to evaluate the truth of far-flung information.Footnote 42 One of these technologies was the emergence of “experts” who represented abstract bodies of knowledge and offered evaluational services (expertise) to laypeople.Footnote 43

The problem of “verification” did not only exist in Europe. In nineteenth century China, Seeking Truth from Facts became associated with verification and trustworthiness, primarily as a result of the increasing size and complexity of the Qing Empire. With a rapidly increasing population, contact with European empires, and the need for military strategies to subdue Central Asia, the Qing required knowledge of rapidly changing local situations. In many cases the Qing succeeded—such as in their conquest of the Dzungar Empire in present-day Xinjiang. In other areas, however, Qing intelligence could be highly deficient—such as Qing geopolitical information about Europeans.Footnote 44 Information gathering was increasingly important, but also treacherous, as a lack of organized experts meant the Qing was frequently behind the ball in learning about geopolitical events and industrial techniques. Additionally, longstanding imperial problems of administrative disinformation were exacerbated by Manchu–Han ethnic tensions, leading to epistemic and political crises for the Qing Court.Footnote 45 In order to overcome these information problems, the Qing Court invented new information channels to better monitor officials and assimilate distant information, such as the Palace Memorial and the Grand Council.Footnote 46

One example of this new environment of uncertainty (and the resulting desire for trustworthiness with which shishi qiushi became associated) comes from Qing personnel management. Qing officialdom underwent great changes in the nineteenth century, as magistrates and governors hired a new class of private secretaries (muyou 幕友) to provide subject-matter expertise and draft policies.Footnote 47 Many secretaries had personal connections with officials; however, as the private bureaucracies of high officials such as Zeng Guofan 曾國藩 (1811–1872) expanded, so too did the need for standards of personnel evaluation. Amidst this personnel expansion, Seeking Truth from Facts became a descriptor of the kind of person that Statecraft officials valued.

In the nineteenth century, shishi qiushi as an adjective came to describe someone who was dutiful, diligent, a policy expert, and thus, hirable. For instance, in the 1860s, Zeng Guofan commented on a report written by the former magistrate Ding Richang 丁日昌 (1823–1882), whom Zeng employed as one of his secretaries. Zeng wrote that,

The submitted report not only lays out the pros and cons of [different methods] of taxation, but also dissects and makes clear the accumulated [evil] habits of the prefecture and county yamens of Jiangxi Province. It is thus sufficient to see that this magistrate gives his attention every day to governing his subordinates; his [attitude] of Seeking Truth from Facts can be greatly commended.

據稟各條, 不獨於丁漕利弊確切指陳, 且於江省各州縣衙門積習, 疏剔明暢。足見該令素日留心吏治, 實事求是, 殊可嘉獎。

Later in his career, Ding was particularly successful in reforming tax systems that had broken down under the accumulating machinations of yamen runners and rural gentry, and which were exacerbated by the Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864).Footnote 48 As Financial Commissioner and Governor of Jiangsu from 1867–1870, to raise taxes Ding brought in new settlers for reclaimed land, enrolled them into tax registers, and hired clerks to oversee taxation, all the while ensuring that no magistrates fabricated registers.Footnote 49 Seeking Truth from Facts in this context indicated Ding’s expertise and competence as an administrator and policymaker.

In Zeng’s appraisal of Ding, we see the kind of limited reflexivity valued by Statecraft scholars: an ability to think of novel solutions to problems of the day while remaining within the contours of the Qing bureaucracy. Ding’s rapid rise (from secretary, to county magistrate, to head of the Jiangnan Arsenal, to Governor of Jiangsu) was likely a result of his patrons’ evaluation of his abilities along these lines. Ding’s situation hints at the peculiar place of expertise in the late Qing: although experts in policy, science, and weaponry were increasingly valued and employed, they still functioned within and attempted to buttress a relatively stagnant imperial system and its ruling ideology. Scientific expertise was and would remain subordinated to Chinese state authority; nevertheless, experts became an increasingly important part of Chinese state verification and policymaking.

Zeng Guofan, syncretism, and science in China

In addition to reflexivity and verification, the final attribute attached to shishi qiushi during the Qing was syncretism. In late-nineteenth century China, shishi qiushi became a “boundary object” linking together disparate ideas and groups into a common discourse and epistemic values.Footnote 50 In early modern Europe, natural philosophy played a similar role: although by the nineteenth century, science came to be valued on its own terms, in the seventeenth century it initially won supporters through functioning as a “handmaiden” to theology, spur to industry, and aid to imperial statecraft.Footnote 51 In China, religion was not a key part of this story. While the Jesuits had attempted to create a link between science and Christianity in the seventeenth century, they found limited success.Footnote 52 Rather, shishi qiushi acted as a handmaiden to science, bringing together science and the nascent idea of a “traditional Chinese culture.”

Crucial to this story of syncretism is Zeng Guofan. Zeng exemplified the new breed of late-Qing Statecraft official, but was also singular in his desire to overcome what he saw as unnecessary divisiveness and vitriol between evidentiary scholarship and Neo-Confucianism. By positing shishi qiushi as a fundamental Confucian empirical ideal that transcended any one intellectual tradition, Zeng turned Seeking Truth from Facts into a boundary object that could help mediate late-Qing intellectual divides. Due to the efforts of Zeng and others, shishi qiushi came to be seen as a virtuous quality in and of itself, independent of any one political or scholarly allegiance.

Zeng Guofan’s promotion of shishi qiushi as a syncretic quality also had unintended consequences, as shishi qiushi quickly became a source of prestige that Qing scholars could appeal to when attempting to legitimize unfamiliar forms of knowledge, such as Western science. Although Zeng promoted science in China in a limited fashion, it was the Protestant missionaries translating scientific texts into classical Chinese that first began to argue for the overlap of shishi qiushi with the scientific spirit. The result was that shishi qiushi came to represent a way of being both scientific and Chinese, universal and particular.

Similar to Chen Hongmou, Zeng Guofan was a devout Neo-Confucian moralist who believed that self-cultivation, strict adherence to ritual, and study of Neo-Confucian texts were all important preconditions for governance. Although Zeng was not opposed to evidential scholarship (known as “Han Learning”), he feared the acrimony that had developed between promoters of philology and Neo-Confucian philosophy, or “Song Learning.” Zeng attempted to heal this rift by arguing that Han and Song Learning were all part of the same tradition of Chinese empirical study, which dated back to the sages of antiquity. Zeng drew equivalences between Han and Song Learning by comparing shishi qiushi with Zhu Xi’s famous epistemological tenets. Zeng wrote:

In this age, starting with the Qianlong and Jiaqing reigns, all scholars strove for broad erudition. Hui Dong, Dai Zhen and those like them dove deeply into philology and etymology, embodying the attitude of King Xian of Hejian: Seeking Truth from Facts. They disparaged the worthies of the Song as vacuous. However, are the so-called “facts” not “things”? Is “truth” not “principles”? Is “Seeking Truth from Facts” not Master Zhu’s “approach things and exhaust their principle?”Footnote 53

近世乾嘉之開, 諸儒務為浩博。惠定宇、戴東原之流鉤研詁訓, 本河間獻王實事求是之旨, 薄宋賢為空疏。夫所謂事者非物乎, 是者非理乎, 實事求是, 非即朱子所稱即物窮理者乎?

Zeng indicated that for him, Qing philology was only the most recent branch of a broader, more ancient empirical tradition in which Song Learning also shared, thus nullifying the critiques of Han Learning advocates that Song Learning was divorced from antiquity and authentic tradition.

Zeng papered over some uncomfortable historical realities. Zhu Xi’s epistemological stance was largely directed towards the moral and ritual world, not towards nature or the bureaucracy.Footnote 54 In downplaying the differences between Zhu Xi, Han Learning, and Statecraft, Zeng opened himself up to later criticism by historians such as Joseph Levenson that he had contributed to the museumification of the Confucian tradition.Footnote 55 However, in suggesting an irreconcilable contradiction between science and Confucianism, Levenson might have overlooked how by the mid-nineteenth century, Qing elites had become beholden to a new epistemic ideal that allowed for the absorption of new forms of knowledge without sacrificing an authentic kernel of belief: shishi qiushi. The challenge that natural empiricism in the form of science posed to Confucianism was eased by Chinese intellectuals’ conscious embrace of novelty, focus on finding solutions to concrete problems, and a syncretic urge to discover “principles” everywhere.

In the late nineteenth century, this syncretic impulse expanded, and Seeking Truth from Facts became indelibly associated with Western science. “Science” was first translated into classical Chinese using the Song term “investigating things to extend knowledge” (gewu zhizhi 格物致知), and later, the Japanese neologism kexue (科學). An important forum in which shishi qiushi became attached to science were the translation projects funded by Zeng Guofan and Li Hongzhang 李鴻章 (1823–1901), which translated Western scientific texts into classical Chinese. In the 1860s, powerful, quasi-independent officials like Zeng and Li sought to build their own Western-style military and industrial machinery, whose power they had witnessed during the Opium War (1839–1942) and Taiping Rebellion. These officials believed that training Chinese scholars in Western technical arts was a crucial step for the Qing to develop modern weaponry. To translate European scientific and engineering texts into Chinese, they established a translation bureau within the Jiangnan Arsenal, as well as the Tongwen Guan (同文馆) in Beijing, whose main instructors were Western missionaries such as W.A.P. Martin (1827–1916) and John Fryer (1839–1928).Footnote 56 Although the audience of these translations was at first limited to the small coterie of Chinese scholars interested in Western learning, it would rapidly expand as Chinese elites became increasingly concerned about the viability of the Qing empire, and looked to the West for inspiration.

As a part of these efforts, Fryer and the well-known translator Xu Shou 徐壽 (1818–1884) founded the Chinese Scientific Magazine (Gezhi huibian 格致彙編), in which they translated the spirit of scientific inquiry as “Seeking Truth from Facts.”Footnote 57 At the same time, Fryer and Xu disparaged the philology with which shishi qiushi was associated, contrasting the “scientific” approach to knowledge production with non-scientific approaches concerned with “ancient texts.” In the eighth issue of the magazine, they introduced the microscope to their readers:

Microscopes are an indispensable instrument in elementary instruction. Today, the most capable [Chinese] people want to switch toward Western Learning, to Seek Truth from Facts. They do not engage in the philological study of ancient texts. Instead, by means of the strength and precision of contemporary physics, science and natural history have become the most important subjects in the classroom. But relying on eyesight cannot give us true precision. For instance, when looking at the leaves of a tree, one only sees its green color, pattern, and the shape of its edges, some flat, some curved, some serrated. People do not generally know that leaves possess an ingenuity beyond that of any machine which humans can build. But when using a microscope to peer at ordinary leaves, one realizes that they are formed from innumerable micro-components merged together, with each component possessing its own function. There are small perforations that suck in air, tubes that can gather and digest nutrients, and veins that circulate liquid and leave the leaf firm and sleek. With human eyes, one cannot clearly see this, but through a microscope, its image is clear. Thus, reading about something over and over again is nothing compared to seeing it for oneself.Footnote 58

Knowingly or not, this passage drew an interesting parallel to a passage written by Wang Yangming in the sixteenth century, in which he described how he had adopted a literal interpretation of Zhu Xi’s imperative to “investigate things,” and attempted to understand the “principle” of a bamboo stalk for seven days, with no apparent knowledge gained. Quickly giving up, Wang turned inwards, focusing on becoming a sage through “a continuous process of internal self-renewal.”Footnote 59 The writings of these nineteenth century missionary editors implied that Wang’s fundamental assumption was flawed: “principles” could indeed be derived from common plants if one knew where to look and had the proper tools to do so. Through articles such as this, shishi qiushi became indelibly associated with Western science, and science became seen as fulfilling the same goals that Zhu Xi had proclaimed, although via a different route.

Part two: Republican dissemination

Republican epistemic anxieties: Science, novelty, and fraud

By 1911, the qualities attached to shishi qiushi were more or less fixed: reflexivity, expertise, and syncretism. Before the Republican period, however, the use of Seeking Truth From Facts was mostly limited to philologists and Statecraft officials. During the 1920s and 1930s, the term spread on the wings of the popular press, taking on new functions and coming to symbolize both China and science, not only in advertising slogans, but in calls for revolution as well.

In the early twentieth century, shishi qiushi spread widely and became further linked to the question of verification and trust within a changing, novel environment. Starting in the late nineteenth century, China rapidly urbanized through its position in European colonial networks. New commodities, ideas, and forms of association flowed across China’s borders, creating an effervescent and unstable foment. In this context, shishi qiushi came to reflect the uncertainty of ordinary Chinese citizens about who they were, what they were consuming, and where their country was going. Within this uncertain environment, Western science came to enjoy unprecedented authority, and Seeking Truth from Facts became almost identical with both a scientific spirit as well as classical Chinese erudition; shishi qiushi could tell people where they came from (the classical tradition), where they were going (science), and offered the possibility of synergy between the two.

One microcosm of this environment of uncertainty were the consumer practices of Shanghai urbanites. Newspapers published commercial advertisements for imported and domestically produced goods of a staggering variety, ranging from cigarettes and monosodium glutamate to cars, perfume, and gramophones. This produced many new and unsettling questions for Chinese consumers. How was a consumer to choose among various products and brands? This problem was made all the more daunting because of the omnipresence of counterfeiting.Footnote 60

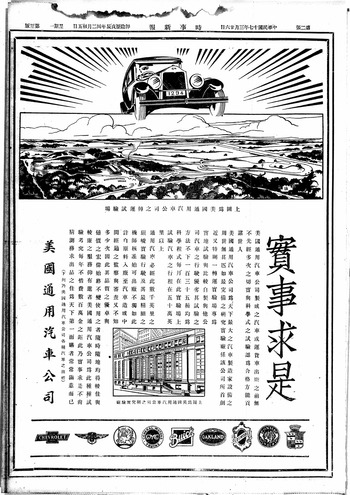

In confronting this novel landscape, “science” became a source of great authority, as did shishi qiushi, which came to mean something like “scientific, reliable, and honest.” Newspaper advertisements described their products and companies as shishi qiushi, implying that they were not counterfeit, not hiding defects, and instead were well-made by honest, technically proficient companies. One advertisement for General Motors automobiles appeared in the Shishi xinbao (時事新报) in 1928 (Figure 1), stating that,

Before American General Motors cars or trucks leave the factory, they all undergo multiple rounds of strenuous and scientific testing. Only when we decide they meet our standards are they offered to the public.

美國通用汽車公司製成之汽車或運貨車, 出廠之前無不先經多次之切實與科學式之試驗; 認為合格方能貢諸世人。

Figure 1. “Seeking Truth from Facts,” GMC advertisement, Shishi xinbao 時事新报 (Shanghai, China), March 26, 1928.Footnote 64

The advertisement featured a beautiful new car and an image of the testing center it had passed through. Written in classical Chinese without punctuation, the advertisement harkened back to a nostalgia-laden Chinese literati culture, while also promoting quintessentially modern products and scientific credibility. Many other advertisements similarly attempted to use traditional culture to sell their products. This nostalgia was most explicitly cultivated in the “Native Products” (guohuo 國貨) movement of the late 1920s, which not only advocated for Chinese consumers to buy Chinese-made products, but also for Chinese men and women to dress and consume in ways that reflected their heritage.Footnote 61

This fusion of classical imprimatur and scientific authority was also reflected in scholarship, in what was called the “National Essence” (guocui 國粹) movement. Initiated by the well-known philologist and anti-Manchu nationalist Zhang Binglin 章炳麟 (1869–1936), the idea of National Essence was wrapped up in the efforts of Zhang and others to collect and publish books they deemed to be central to the history of the “Han race.”Footnote 62 Promoters of National Essence scholarship did not reject modernity, but rather sought to create a synthesis that valued the Chinese past.Footnote 63 In biographies of Qing literati published in the magazine National Essence Learning (Guocui xuebao 國粹學報), National Essence advocates used Seeking Truth from Facts to epitomize this synthetic orientation. For instance, in introducing a letter by the nineteenth-century literatus Wang Xisun 汪喜孫 (1786–1848), the editor stated that, “in his scholarship, he sought truth from facts, studying Han Learning but not discarding Song Learning.”Footnote 65 Like Zeng Guofan’s syncretism, many Republican Chinese consumers and intellectuals sought to reconcile the “new” science with the “old” literati culture; shishi qiushi helped them to form this bridge.Footnote 66

Mao Zedong’s revolutionary epistemology

The course of the genealogy of shishi qiushi was forever changed by its contact with Mao Zedong. Mao valued shishi qiushi for the same reasons as many of his contemporaries: its embodiment of being both classical and scientific, Chinese and modern. Mao also valued its reflexivity, and argued that through the collective research of cadres who “Seek Truth from Facts,” the CPC could reflexively update its knowledge base and ensure that policies would not lag behind rapidly changing events and environments.Footnote 67 At the same time, Mao also valued shishi qiushi for its ability to aid the CPC in verifying wartime intelligence: Mao believed that truth-loving cadres steeped in the ethos of shishi qiushi would not defraud the state by submitting false information. In 1941, Mao promoted shishi qiushi across the Party as part of the Rectification Movement, and empirical investigation became an important aspect of Party work.

Born outside of Changsha, Hunan in 1893, Mao Zedong was not a cosmopolitan urbanite, and did not engage in the emerging consumerism that came to define Shanghai’s bourgeoisie. Rather, he was one of the multitude of rural intellectuals who grew up in gentry families, and whose formative education was in the Classics and literati writings. But Mao also grew up alongside the flood of Western scientific thought that inundated early-twentieth century China.Footnote 68 As the scions of the gentry entered new educational institutions, they brought their literacy in classical Chinese and commitment to a life of moral action into contact with the promise of transforming the Chinese nation through natural and social scientific research.

Because of his rural upbringing, it is less likely that Mao would have been exposed to the ethos of shishi qiushi from the commercial advertisements and newspapers of China’s urban centers. But this did not mean that shishi qiushi did not surround Mao as an ideal. For instance, the term appeared in popular books Mao read like Words of Warning to a Prosperous Age (Shengshi weiyan 盛世危言) by the nationalist comprador Zheng Guanying 鄭觀應 (1842–1922).Footnote 69 In addition, while at Hunan First Normal School, Mao became an avid reader of his provincial compatriot Zeng Guofan.Footnote 70 Shishi qiushi was firmly attached to Hunanese Statecraft learning, and was physically inscribed upon the gate of the Yuelu Academy (Yuelu shuyuan 嶽麓書院), which Mao visited as a student.Footnote 71

Mao’s understanding of shishi quishi was inextricably tied to the larger social scientific research movement that exploded in China in the 1920s and 1930s. As young Chinese elites studied abroad, they learned social research methodologies which they then brought home.Footnote 72 Affiliated with a variety of political groups, these idealistic young men and women sought to identify the core “problems/questions” that plagued China.Footnote 73 Many of these intellectuals looked to the Chinese countryside, which was China’s largest economic sphere and which was also seen as particularly backwards.Footnote 74 Pragmatists such as James Yen set up model counties where they attempted to combat illiteracy and unsanitary conditions. Mao developed his own approach to rural social research, which focused on first-hand observation, meetings with local stakeholders, and using Marxist categories to analyze local conditions.

During the 1920s, while he was still a young man, the exigencies of revolution led Mao to carry out a number of informal social surveys. When the CPC’s alliance with the Nationalist Party (KMT) fell apart in 1928, Mao and a small band of CPC cadres fled into the mountainous borderland between Hunan, Jiangxi, and Fujian. There, Mao would spend the next six years building a series of autonomous base areas, or Soviets, which would last until 1934, when the CPC was forced to flee KMT encirclement, embarking on the famous Long March. The initial process of establishing political power in Jiangxi was incredibly fraught: the CPC was confronted with complex local political situations that involved powerful kinship organizations, entrenched gentries, and secret societies.Footnote 75 To understand these local politics, Mao carried out detailed surveys of different counties, and produced summaries of the process of land redistribution.Footnote 76

When he arrived in Yan’an in 1935, Mao had already arrived at a tentative research methodology.Footnote 77 By 1938, Mao became the most powerful military and political leader in the CPC, but he still lacked respect as a Marxist theoretician.Footnote 78 It was in this phase of struggle with the “returned students” from the Soviet Union that Mao linked his research program to the phrase shishi qiushi. Without having studied in the Soviet Union, and with no deep connections to the Comintern, Mao could not claim a superior understanding of the Marxist-Leninist canon than Soviet-trained leaders. However, Mao did possess superior knowledge of China’s domestic conditions, and had practical experience in building revolutionary power. In 1941, Mao argued that, to win the war, the entire CPC needed to Seek Truth from Facts, and that the means of doing so would be for the entire Party to study his rural surveys and carry out “Investigation and Research” (diaocha yanjiu 调查研究). The CPC set up a network of research offices that would carry out rural surveys for the rest of the 1940s.Footnote 79 During the Winter of 1941, Mao provided the calligraphy for an engraving above the entrance the Central Party School. The inscription, carved in stone, read “Seeking Truth from Facts.”Footnote 80 These research offices and the information they provided to Party committees would form an important part of the CPC’s organizational strength, which helped it win the war against Japan, and later the KMT.Footnote 81

In his promotion of shishi qiushi, Mao carried on intellectual legacies originating in seventeenth century China. The way that Mao identified truth with political efficacy mirrored the thinking of Chen Hongmou. For Mao, shishi qiushi meant to discover the “laws” (guilü 规律) of the universe through research, and to update socialist theory accordingly. Mao’s shishi qiushi was also syncretic, seeking a middle ground between scientific research, China’s particular conditions, and Marxism. Finally, Mao’s understanding of Seeking Truth from Facts was related to the problem of verification: by establishing research offices within CPC committees, Mao sought to create a network for verifying social and economic information from far flung locales. The place of expertise within the CPC also had legacies in the imperial past. Like the scholar-officials of the Qing, Mao was wary of independent sources of expertise that could challenge Party authority, and instead sought to create intellectuals who were “Red and Expert,” or knowledgeable in their subject matter and loyal to the Party.Footnote 82 However, achieving the proper balance between expert authority and mass input was tricky, as was revealed in the CPC’s struggles with statistical fraud in the 1950s.

Part three: PRC consolidation

Verification problems in the early PRC

By 1949, shishi qiushi was part of Chinese state ideology and national construction. In the 1950s, the CPC attempted to deploy shishi qiushi to help produce honest and loyal state subjects who would submit accurate statistics to the Party. However, these efforts failed when local cadres and farmers lied about grain production, contributing to the Great Leap famine. At the same time, the CPC vacillated between a stubborn dogmatism that an earlier Mao might have decried, and an extreme reflexivity that led to unrealistic, un-empirical policymaking.

By the time the PRC was founded in 1949, both shishi qiushi and Maoist investigation were associated with the Party’s wartime successes. Mao and the Party believed that this ethos and related research practices would be important to socialist construction. However, research and data gathering in the 1950s were quite different compared to the previous decade. During the war, intellectuals had played an important role in intelligence gathering. However, in the 1950s, these experts clashed with the state over freedom of conscience and economic policies, leading the CPC to view them with increasing suspicion. The balance of “Red versus Expert” tilted towards Red, with Party committees taking charge of data work.Footnote 83 The CPC believed that mass virtue could replace expertise in state data gathering, with millions of farmer-informants embodying shishi qiushi and contributing data to the state. However, this vision would be impossible to realize. CPC information gathering in the 1950s became mired in fraud and misinformation, and the Mao-era was characterized by state–society disconnect. By the end of the 1950s, the CPC found itself in a state of deep epistemic uncertainty. What was the cause of this failure?

Surveillance is a crucial governance task for all modern states.Footnote 84 Starting in the eighteenth century, centralizing European nation-states began to collect agricultural, economic, and social data on a mass scale for the first time in world history.Footnote 85 By the early twentieth century, countries such as France, Germany and England could request statistics from businesses and numerate farmers.Footnote 86 In contrast, Chinese farmers and many businesses did not keep systematic accounts.Footnote 87 China also largely lacked the communities of professional researchers that European states relied on.Footnote 88 The PRC thus faced the prospect of building the required epistemic communities of experts and local informants largely from scratch. This was a huge problem, especially because the CPC had ambitious plans for implementing a centrally planned command economy with massive data requirements.Footnote 89 To solve this “crisis in counting,” the CPC founded data-gathering institutions such as the State Statistical Bureau (Guojia tongjiju 国家统计局), tasked with gathering the data required for compiling annual and five year plans.Footnote 90 However, it quickly became apparent that information gathering would not be a straightforward endeavor. For one, the pure scale of the PRC economy and lack of trained personnel meant that the CPC faced immense difficulties in gathering statistics. More sinisterly, the intentional fabrication of information would become a major problem for the PRC.

False reporting went by a number of names (jiabao 假报, xubao 虚报, shaobao 少报, huangbao 谎报, fukua 浮夸, manchan 瞒产), but in each instance it had the same cause: the recognition by local cadres and farmers that state information gathering directly impacted their material lives. By exaggerating local production numbers, local officials could impress their superiors. By underreporting, local cadres and farmers could avoid taxation and grain procurement. False reporting worsened over the course of the 1950s, exacerbated by increasing state control of grain and industrial materials. After the policy of Unified Purchase and Sale (tonggou tongxiao 统购统销) was implemented in 1953, the PRC began to purchase all “surplus grain” (yuliang 余粮) left over after subtracting that which was needed for local fodder, seed, and consumption. Due to this policy, agricultural statistics became a battlefield upon which local governments negotiated how much grain would remain locally.Footnote 91

Because of the weakness of PRC statistics, the exact amount of grain harvested per year and stored at the sub-county level was usually unclear even to county officials. CPC leaders at the national, provincial, and county level all needed to determine how much grain could be procured from the areas under their jurisdiction. In this context, Seeking Truth from Facts became associated with the difficult work of determining exactly how much grain existed at the local level. This problem of mass verification was extremely fraught: localized famines occurred throughout the 1950s due to local officials over-estimating grain yields and refusing to listen to farmers’ complaints about hunger. After these famines were brought to light, the responsible county party secretaries were castigated as “lacking the spirit of Seeking Truth from Facts.”Footnote 92

This positioning of Seeking Truth from Facts as the opposite of false reporting continued during the Great Leap Forward (1958–1961), during which the fabrication of grain and steel production reached unprecedented heights.Footnote 93 Although the Party Center itself helped to cause this false reporting due to the political pressure it placed on cadres, leaders including Mao were scandalized by the sheer scale of false reporting. A bizarre scenario emerged in which official newspapers simultaneously celebrated the fabricated accomplishments of the Great Leap while also calling on cadres to Seek Truth from Facts and honestly report grain yields.Footnote 94

This chaotic state of affairs reflected the difficulties of maintaining the values of both reflexivity and verification within regimes of Stalinist economic planning. In some ways, the CPC embodied the tradition of reflexivity when it cited Mao in telling cadres how they should be watchful for “new things” (xin shiwu 新事物) that could emerge during socialism—such as record harvests—which could change the national economic calculus.Footnote 95 Yet Mao’s extreme reflexivity often came into conflict with the need for empirical verification. The desire to embrace “new things” overlooked the cold hard fact that the face of China had not changed: grain production had not skyrocketed, farmers were resistant to state procurement, and false reporting was worse than ever. The empirical basis of the CPC’s truth-seeking became perverted by over-optimistic, wishful thinking, and reflexivity without verification.

Deng Xiaoping and the search for a new socialist path

Although Mao’s reputation was forever tarnished by the Great Leap, the reputation of shishi qiushi was higher than ever. When the worst of the famine had ended by 1962, CPC leadership reflected on what had happened, and reached a consensus that CPC leadership had pressured local cadres to lie, and therefore had not exemplified the ethos of shishi qiushi. Footnote 96 As a result, the Party made 1961 the “Year of Investigation and Research,” and sent Beijing-based cadres down to the countryside to inquire into local economic circumstances.Footnote 97 The shocking wreckage they found there contributed to the rise of moderate agricultural policies from 1962–1963. However, this moderation was interrupted by the eruption of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. After a decade of political chaos, Mao Zedong passed away in 1976. Following a brief power transition, the CPC embarked on the reforms that have defined contemporary China. Shishi qiushi played an important and underappreciated role in these reforms, which were partially driven by reformers who rallied around shishi qiushi as an epistemic ethos whose moderate reflexivity and empiricism could be deployed to help salvage the Chinese revolution. The ideal of Seeking Truth from Facts helped to spur the establishment of new research institutions, and to articulate a new understanding of socialism itself.

After the death of Mao Zedong in autumn 1976, the CPC was pushed into a deep epistemic crisis and uncertainty about the future of Chinese socialism. CPC leadership questioned the Soviet model of economic planning, the endless political campaigns, as well as the subordination of expertise to revolutionary loyalty and the mass line. In debates that emerged within Party journals and the press, CPC leaders argued these problems stemmed from dogmatism, an emphasis on book learning, rote copying of foreign models, and following administrative dictates that ignored both universal “economic laws” (jingji guilü 经济规律) and China’s “national conditions” (guoqing 国情).Footnote 98

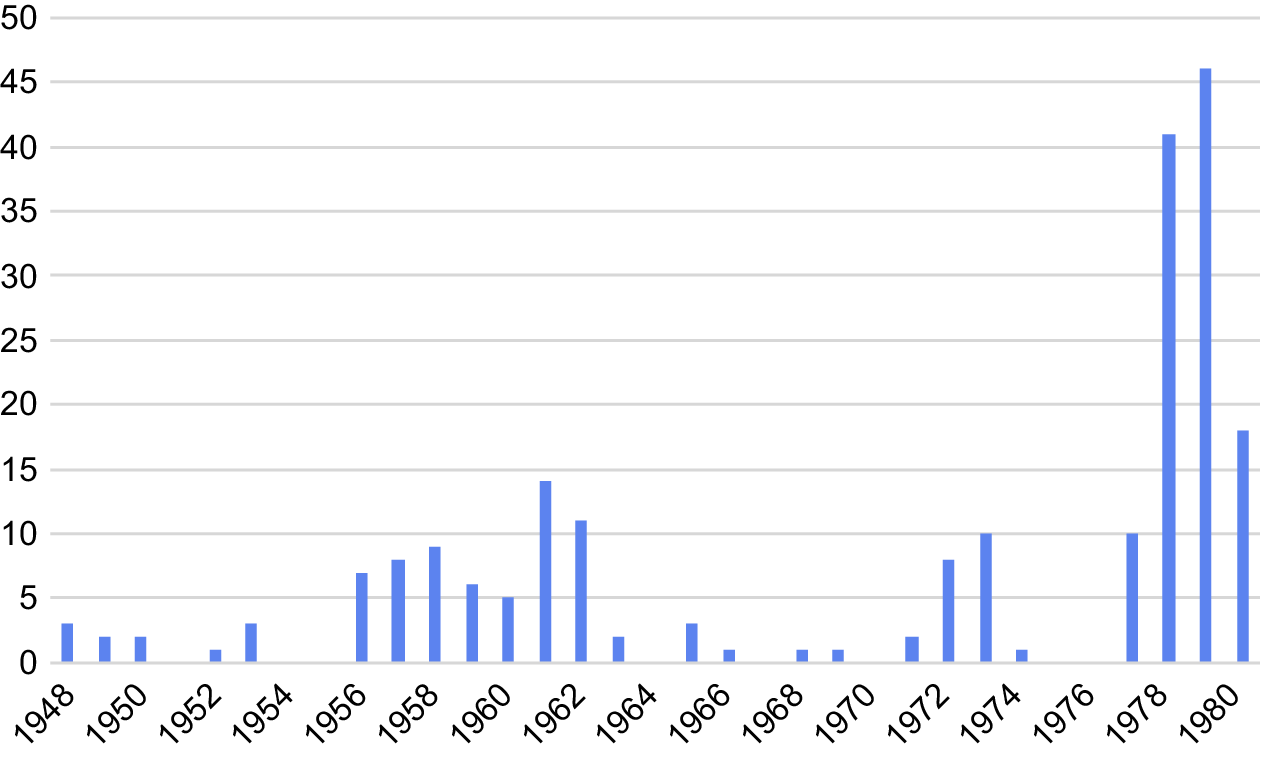

In early 1978, assistant director of the Central Party School Hu Yaobang 胡耀邦 (1915–1989) helped initiate a well-known publicity campaign that brought these issues into the center of national Party life: the “Practice is the Sole Criterion of Determining Truth” campaign (shijian shi jianyan zhenli de weiyi biaozhun 实践是检验真理的唯一标准).Footnote 99 An important effect of the campaign was to create a new intellectual consensus within the CPC on the need to be more committed to empirical research and science-based policymaking. The central symbols around which this consensus congealed were Investigation and Research and Seeking Truth from Facts. Shishi qiushi was valorized in the press, as can be seen in the increasing number of People’s Daily articles with shishi qiushi in their title (Figure 2).

Figure 2. People’s Daily articles with shishi qiushi in the title. Compiled using the OriProbe People’s Daily Online Database.

It is of course somewhat strange that an epistemic ethos should be placed at the center of the Party’s quest for rejuvenation. The reason for this is likely that after a decade of factional strife and political chaos, shishi qiushi was one of the few things that everyone in the Party could agree upon as an undisputed good. The multivalent meaning of shishi qiushi allowed it to function as a boundary object linking together the entire CPC. Separated from the wartime period by thirty years, the CPC imagined a mythical Yan’an in which empiricism reigned and dogmatism was rejected. The names of new journals published by provincial Party schools revealed how they saw themselves as inheritors of Yan’an legacies: the Xinjiang Provincial Party School’s journal Seeking Truth from Facts was first published in 1978; the Jiangxi Party School’s Truth Seeking (Qiushi 求实) in 1979. Today, the CPC’s primary theoretical journal is titled Seeking Truth (Qiushi 求是).

This was not mere intellectual wrangling; it produced tangible results in the form of new think tanks and academic committees such as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan 中国社会科学院) and Central Party School (Zhongyang dangxiao 中央党校), both established in 1977. Long-shuttered universities reopened, and the CPC publicly committed itself to modernizing PRC scientific research. Missile scientists, agrarian reformers, and economists were quickly given positions in new consultative bodies that advised the Party Center. By 1980, this new milieu of expert-informed policymaking helped produce the One Child policy as well as decollectivization.Footnote 100 The balance between “Red versus Expert” now swung towards expertise.

This change in CPC policymaking occurred alongside a shift in how the Party viewed itself and Chinese history. Like Chen Hongmou before them, CPC leaders generally believed that following and mobilizing natural and economic “laws” was the best path to successful governance. However, there were disagreements over what these laws were, and whether they were static or shifting. Mao had followed Marx and Stalin in assuming that certain economic laws could change as history progressed. The “laws” that occurred in capitalist countries—such as rational self-interest—might not apply under socialism. This perspective contributed to a widespread belief in the Mao-era CPC that transforming the political consciousness and “backwards” mentalities of the peasantry was necessary to ensure the success of collectivization.Footnote 101 At the same time, as was the case with Chen Hongmou, the CPC believed that the best way to test the truth of natural or economic laws was through evaluating the success or failure of governance. In the late 1970s, CPC leaders lost faith in their own power to shape the mentalities of farmers and workers, and came to accept the existence of transhistorical “economic laws,” which they then sought to discover and mobilize.Footnote 102 This was part of a much broader shift in the socialist world, which increasingly rejected heavy-handed Stalinist models of state-driven economic and social engineering, and made room for market mechanisms, individual initiative, and science.Footnote 103

This effervescence of new ideas and institutions culminated in the idea of “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics,” which Deng Xiaoping announced during the opening remarks to the Twelfth National Congress of the CPC in 1982.Footnote 104

A new path forward had been discovered for Chinese socialism, ending the period of epistemic uncertainty that had plagued the CPC since the mid-1970s. Shishi qiushi and Investigation and Research would play an important role within this new understanding of China’s future. Socialism in China would no longer be seen through a Stalinist teleology proceeding rapidly to rural communes and heavy industry. Instead, the form of Chinese socialism would be more indeterminate, and suitable to both China’s particular “national conditions” and universal “economic laws.” To discover these laws would require the Party’s embodiment of the attitude of shishi qiushi, and be manifested through a new and productive relationship between scientific experts, cadres, and Party leadership.

Conclusion

Within “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics” and contemporary CPC state ideology, one can observe epistemic traits that first became attached to shishi qiushi during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: reflexivity, expertise, and syncretism. Beginning with Qing philologists, Chinese elites have been reflexive in their openness to following the perceived dictates of natural and social laws. To do so required verifying uncertain information. Because of this, Chinese elites have come to valorize scientific expertise. Finally, syncretism has been driven by an urge to be both Chinese and scientific; to be broad minded but also rooted in place.

Seeking Truth from Facts is a palimpsest: each usage leaves traces in its subsequent expression. Although shishi qiushi always speaks to the specific situation in which its collective authors find themselves, these authors also convey meanings inscribed by shishi qiushi’s previous iterations. Each of the three snapshots described here left their mark: shishi qiushi now means to be modern and scientific, Marxist, truthful, and Chinese. It means to engage with problems inherent to modernity, such as the verification of distant information, and calls on its adherents to refuse teleological closures and to embrace reflexivity in their intellectual inquiry.

The history of shishi qiushi reveals how embracing uncertainty lies at the heart of modern Chinese intellectual life. With population growth, a complex and expanding bureaucracy, and novel geopolitical realities, early modern Chinese elites were all too clear on the need for learning that might address these issues. At the same time, the Neo-Confucian imperial ideology that lasted since the fourteenth century—and the authenticity of its supporting texts—were increasingly subjected to intense scrutiny and outright suspicion. Exposure to scientific thinking presented additional challenges to traditional cosmologies. By the late-nineteenth century, this chaotic influx of new ideas, forms of association, and fragile political stability, produced a new settlement: Chinese elites were increasingly ready to abandon received intellectual traditions in favor of new and convincing ideas, the evidence for whose validity was to be produced in the realm of political, economic, and social praxis. Within the shifting historical contexts of the coming centuries, the epistemic ideal of shishi qiushi remained a cynosure, curiously functioning to both validate the abandonment of old ideas for new ones, yet also generating a sense of intellectual continuity that linked Chinese intellectuals to their forebears.

Shishi qiushi reveals the epistemic optimism of modern Chinese intellectual life, in that shishi qiushi offered a connection not just to the past, but to the future. Though often pessimistic about the times in which they lived, Chinese intellectuals believed that, despite having given up an intellectual heritage of great value, they were gaining something greater in return. New, better truths would replace lesser, outdated ones; older, outdated modes of social organization would fall away, fondly remembered, but gone.

Competing interests

The author declares none.