1. Introduction

The study of vowel quality has traditionally been based on single-point formant frequency measurements which provide a static cross-sectional view of the vowels under examination. Although the limitation of this static approach was acknowledged by Tiffany (Reference Tiffany1953), who noted the role of vowel duration and changes in formant frequencies over time in vowel perception, the term Vowel Inherent Spectral Change (VISC) was only coined in 1986 by Nearey & Assmann (Reference Nearey and Assmann1986). VISC analysis has since been increasingly adopted in descriptive studies of different inner circle varieties of English, such as American English (Fox & Jacewicz Reference Fox and Jacewicz2009), British English (Williams & Escudero Reference Williams and Escudero2014), and Western Sydney Australian English (Elvin et al. Reference Elvin, Williams and Escudero2016). More recently, VISC is progressively used in the investigation of vowel shift (e.g. Renwick & Stanley Reference Renwick and Stanley2017; Stanley Reference Stanley2020). There is considerable evidence now acknowledging spectral change as an essential part of the vowel system; even for nominal monophthongal English vowels (Hillenbrand Reference Hillenbrand, Stewart Morrison and Assmann2013; Schwartz Reference Schwartz2021).

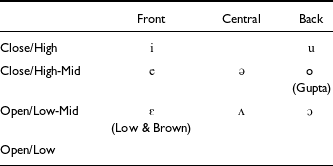

Table 1. Distribution of seven monophthongs based on Gupta (Reference Gupta1994) and Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005)

1.1 Past descriptions of Singapore English vowels

Singapore English is a postcolonial English that has been recognized as a nativized variety (Wee Reference Wee, Wee, Goh and Lim2013; Tan Reference Tan2014), with the younger generations of speakers acquiring it as their mother tongue. In terms of its sound system, it has a syllable-timed rhythm, as pointed out by Deterding (2001; Reference Deterding2007) and Low et al. (Reference Low, Grabe and Nolan2000). There is no tendency towards vowel reduction in monosyllabic function words and syllables containing /ə/ (Deterding Reference Deterding2007:28). Hence, syllabic consonants are not a feature of Singapore English. It is also a non-rhotic variety, with instances of the postvocalic /r/ categorized as an emergent feature of low occurrence among a minority of speakers, as demonstrated by Tan (Reference Tan2012; Reference Tan, Hashim, Leitner and Wolf2016) and Kwek (Reference Kwek2017). Particularly, much has been said about its lack of monophthong pair contrast and the reduction of specific diphthongs, and this section will provide a summary of what is common among past observations on these aspects of Singapore English vowels.

Previous descriptions of Singapore English vowels have generally been impressionistic. Of the more comprehensive descriptions by Gupta (Reference Gupta1994), Bao (Reference Bao1998), Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004), Wee (Reference Wee, Bernd Kortmann, Mesthrie, Schneider and Upton2004), Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007), only Deterding offered an analysis based on formant frequency measurements, and single-point readings for monophthongs at that. Altogether, these past descriptions have collectively identified seven to nine monophthongs in Singapore English. All concur on the conflation of the vowel sounds /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/, /ɜ, ə/ and /æ, ɛ/, where tense-lax vowel pair contrast is not found. The possible distributions of these monophthongs are illustrated in Tables 1–3.

Table 1 shows the distribution of monophthongs as described by Gupta (Reference Gupta1994) and Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005). Both Gupta and Low & Brown specify seven monophthongs each; both have the vowels [i, u, e, ə, ʌ, ɔ] in common, while Gupta includes [o] and Low & Brown has [ɛ].

The seven monophthongs suggested in Gupta as a ‘reasonable guide to the sound of the vowels of most varieties of Singapore English’ (1994: 9) are essentially the same set as Deterding’s (see Table 2), except for the absence of [ɛ] in Gupta’s. With only seven monophthongs in Gupta’s analysis, the vowels in dress, trap, square and face are all observed as [e]; no vowels are pronounced [ɛ]. Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005:127) adopt Gupta’s analysis with some modification. Similar to the observations of Deterding and Lim (as shown in Table 2), Low & Brown identify the vowels in dress, trap, square as [ɛ] and the vowel in face as [e]. The other difference is the vowel in goat, which Gupta perceives as [o] and Low & Brown describes as the diphthong [oʊ].

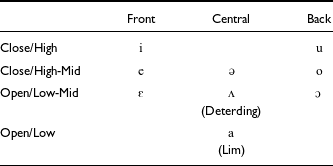

Table 2 shows the distributions of the eight monophthongs respectively based on the descriptions of Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007). The observations of Deterding and Lim are almost identical, except for the vowel in the keywords strut, bath and palm. Where Deterding analyzes it as [ʌ], Lim describes it as the lower more frontal [a]. None of the above descriptions perceives the vowel in face as [ei] but there is no consensus on the identification of the vowel in goat as a diphthong or a monophthong.

Table 2. Distribution of eight monophthongs based on Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007)

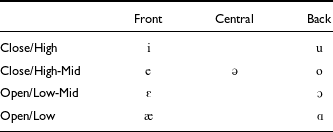

Table 3 shows the distribution of the nine monophthongs as described by Bao (Reference Bao1998) and Wee (Reference Wee, Bernd Kortmann, Mesthrie, Schneider and Upton2004). Compared to the monophthongs described in Gupta (Reference Gupta1994), Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005), Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007), there is the additional low front vowel [æ] and the low back vowel [ɑ] instead of [ʌ]. According to Bao (Reference Bao1998:155), [e], [æ] and [o] are the realizations of the diphthongs /eɪ/, /ɛə/ and /oʊ/. Although he made no reference to the keywords in Wells’ standard lexical sets (1982), his observations are similar to Wee’s perceptions of [e], [æ] and [o] as the vowels in face, square and goat. All six descriptions above identify the vowel in face as [e], and with the exception of Low & Brown, they similarly identify the vowel in goat as [o].

Table 3. Distribution of nine monophthongs based on Bao (Reference Bao1998) and Wee (Reference Wee, Bernd Kortmann, Mesthrie, Schneider and Upton2004)

With the target diphthongs /eɪ/, /ɛə/ and /oʊ/ reduced to monophthongs, the number of diphthongs is undisputed in the works of Gupta (Reference Gupta1994), Bao (Reference Bao1998), Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004), Wee (Reference Wee, Bernd Kortmann, Mesthrie, Schneider and Upton2004) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007). The five diphthongs are /ai/, /ɔi/, /au/, /iə/ and /uə/, as in the vowels in price, choice, mouth, near and poor respectively. The only exception is Low & Brown’s inclusion of the diphthong /oʊ/ for goat.

At this juncture, it is important to clarify that for the purposes of the present study, there will be no a priori assumption that any of the above past observations will be found in the dataset examined. All potential phonemes will be considered, independent of the above descriptions.

1.2 Objective of the present study

The present study stems from a comprehensive sociophonetic examination of Singapore English vowels by C. Low (Reference Low2023) which finds ethnicity and age differences to correlate strongly with vowel sound variation through the analyses of VISC and vowel duration. Using the same dataset and methods, this study similarly analyzes the VISC of Singapore English vowels and examines possible contrast in duration between its tense-lax vowel pairs. Compared to the single time point references used in past studies (as summarized in section 1.1), the present study aims to determine if the same conflations of the monophthong pairs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/, /æ, ɛ/ and /ɜ, ə/ and diphthong reductions of /ɛi/, /ɛə/ and /oʊ/ are observable through the more dynamic and finer grained VISC method along with vowel duration analysis. Especially since the past descriptions were published more than 18 years ago, the present study also aims to provide an update on the description of the vowel system.

2. Materials and methods

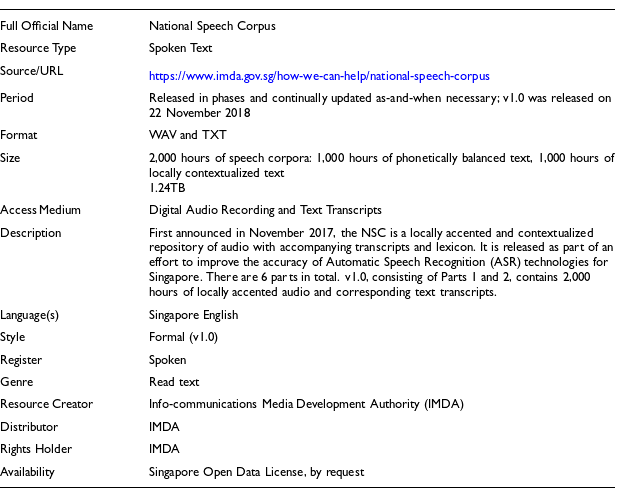

This study is based on data from Version 1.0 of the National Speech Corpus (NSC), the very first large-scale public corpus of spoken Singapore English. Compiled by the Infocomm and Media Development Authority (IMDA), a Singapore government statutory board that develops and regulates its info-communications and media sectors, the NSC was developed to provide a repository of locally accented and contextualized speech to support the development and improvement of automatic speech recognition technologies for use in Singapore.

2.1 The phonetically balanced sub-corpus of the NSC

Released in November 2018, Part 1: Phonetically Balanced Text of the NSC Version 1.0 consists of 1,000 hours of read speech based on about 72,000 sentences extracted and adapted from Singapore news websites and is further supplemented with 200 specially crafted sentences to ensure the representation of all documented phones of Singapore English in the corpus. These 200 standard sentences were assigned to every speaker, while additional sentences were assigned using an algorithm that factored in the human capacity and time limitations of the recording sessions (Koh et al. Reference Koh, Mislan, Kevin Khoo, Ang, Ng and Tan2019:322). Table 4 provides a summary of Version 1.0 of the NSC.

Table 4. The National Speech Corpus (NSC) version 1.0

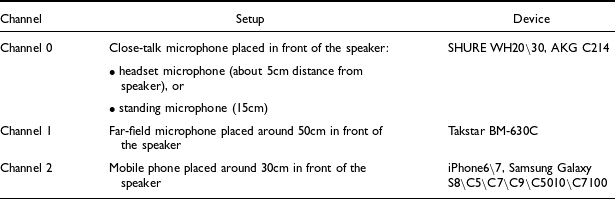

A total of 1,036 speakers from diverse backgrounds and ages were recruited for Part 1 of the NSC Version 1.0. Outsourced to an AI data resource company, the recording took place in recording studios and quiet rooms in co-working spaces in various locations and over a duration of about three months. Three channels were set up for the recording of every speaker using close-talk microphones, far-field microphones and mobile phones. Table 5 shows the setup for each of the recording channels. WAV files from Channel 0 were used for this study.

Table 5. Setup for speech recording

2.2 Selected dataset

Meant for a larger sociophonetic investigation of the variation and change in the vowels of Singapore English, the selected dataset caters to the need for a representative sample across the requisite ethnic groups, educational levels and age ranges (which are the factors examined for correlation with vowel sound variation in the original study, the results of which have been briefly mentioned in section 1.2. The stratified breakdown of the selected speakers is presented in Table 7 in section 2.2.2.). Selection of the dataset is based on the following criteria:

-

• speech material,

-

• speaker profile, and

-

• availability and usability of the relevant sound files.

2.2.1 Speech material

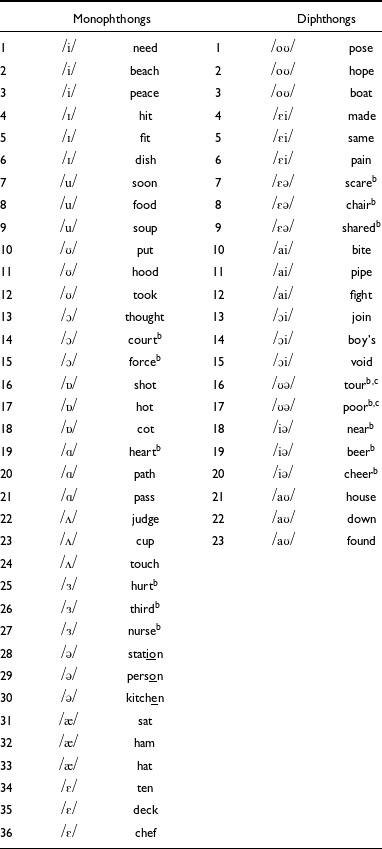

Three tokens for each vowel phoneme in the CVC environment are selected and these are monosyllabic content words, except for the case of /ə/ where bisyllabic words are the next best alternative. To avoid the effects of coarticulation on the vowels’ spectral features and duration as much as possible, vowels in or close to the /hVd/ environment are preferred. Referred to as the “null” environment by Stevens & House (Reference Stevens and House1963), the /hVd/ context is used in Hillenbrand et al. (Reference Hillenbrand, Getty, Clark and Wheeler1995), Hillenbrand, Clark & Nearey (Reference Hillenbrand, Clark and Nearey2001) and adopted in most other sociophonetic studies on vowels.

Table 6. Selected phonemesa and words

Table 7. Stratification of the 148 selected speakers

a Speakers in the secondary education category are those who have attained the Singapore-Cambridge General Certificate of Education (GCE) Normal Level or Ordinary Level as their highest level of education.

b Speakers in the post-secondary category are holders of the GCE Advanced Level or diplomas from non-university higher education programs as their highest educational qualification.

In principle, every speaker in the phonetically balanced sub-corpus would have read the standard set of 200 sentences. Hence, it makes sense to carry out word and phoneme selection from among these 200 sentences. Naturally, the 200 standardized sentences do not offer the full list of /hVd/ or even /bVd/ words. Hence, the additional rules below from Di Paolo et al. (Reference Di Paolo, Yaeger-Dror, Beckford Wassink, Di Paolo and Yaeger-Dror2011:88–89) have served as a guide for the selection, although it is still not possible to fulfil all of the guidelines:

-

• avoid tokens that precede nasals,

-

• avoid tokens that precede velars,

-

• avoid liquids /r/ and /l/,

-

• avoid glides /j/, /w/, and

-

• avoid consonant clusters.

For diphthongs /ɛə/, /ʊə/ and /iə/, exceptions have been made to accommodate the shortage of suitable tokens in the corpus. Hence, words without a final consonant have to be included (i.e. scare, chair, beer, cheer, near, poor and tour). (As mentioned in section 1.1, Singapore English is a non-rhotic variety.) In the case of /ʊə/, there are only two tokens available. Another exception due to a limitation of choice is the word found for /aʊ/ which ends in a two-consonant cluster. Owing to even greater limitations, triphthongs are not explored in this study.

To help with the selection of suitable words, ShinyConc (Wolk & Fastrich Reference Wolk and Fastrich2019) was used to create a custom concordancer running in RStudio (RStudio Team 2021) for the 200-sentence subset of the corpus. Table 6 lists the selected vowels and words.

2.2.2 Speaker profile

According to Koh et al. (Reference Koh, Mislan, Kevin Khoo, Ang, Ng and Tan2019:321), the recruitment of speakers for the NSC conformed to the following criteria:

-

• age 18 years and above, which is the local age requirement for legal consent,

-

• Singapore citizenship and having been raised in Singapore, or Singapore residency and having lived in the country for at least 18 years,

-

• literacy in English, and

-

• formal education in English in a Singapore public school for at least six years.

In addition to the above criteria inherent in the NSC, the data selection for the present study took further steps to limit the possibility of crosslinguistic influences from speakers’ non-English dominant language(s) and eliminate the likely effects of gender-related differences. Hence, only female speakers who have specified English as their first language (L1) are selected. Extensive works on language and gender as well as gender differentiation in language change have revealed significant differences in the linguistic patterns of men and women. Women are more likely to be the gatekeepers in maintaining speech variants associated with overt social prestige or they may be more progressive in adopting incoming non-standard variants (Labov Reference Labov1990:205–206). In general, women are more often found to be the leaders of linguistic change than men (Labov Reference Labov2010:197–199). Hence, only female speakers have been selected for the study.

In the set of recordings stored as individual WAV files for each sentence, not all the speakers are found to have the complete set of 200 sentence files. Moreover, in some of the recordings, parts of sentences have been left out or misread. Hence, the resultant dataset is derived from all available and usable sound files that remain in the set after meticulous checking.

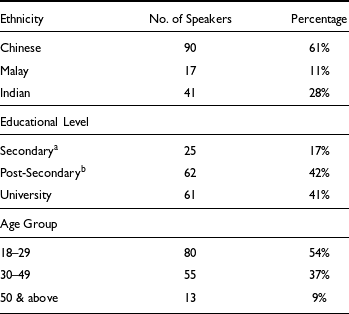

Based on all the above criteria, only female L1 English speakers with the complete set of relevant data files have been selected for the study. There are 148 such speakers in total. Table 7 provides a stratified breakdown of the speakers.

As the NSC was compiled with the aim of reflecting the ethnic composition of Singapore, with a majority of Chinese and minority of Malays and Indians, the 148 speakers in the selected sample also roughly reflects the ethnic composition of the society at large, although not in the exact Chinese : Malay : Indian ratio of 74.3 : 13.5 : 9.0 in percentages as presented in the Census of Population 2020. The breakdown by education listed in the Census of Population 2020 in the ratio of Secondary : Post-Secondary : University is 16.3 : 25.3 : 33.0 (%). Compared to the figures in Table 7, the selected sample of 148 speakers has a higher proportion of Post-Secondary and University level speakers. There is no similar age composition reported in the Census of Population 2020, however.

2.2.3 Singapore English as represented in the NSC

The NSC uses the term Singapore English to refer broadly to locally accented English spoken by Singaporeans or residents who have lived in Singapore for at least 18 years and have had at least six years of formal education in a Singapore public school, as reflected in the speaker requirements (see section 2.2.2). This rules out the possibility of including adult immigrant speakers who would likely maintain their home accents. In this study, the term Singapore English is used in line with the variety represented in Part 1 of the NSC from which the dataset is taken, but with the added requirement that it is speech produced by L1 speakers (as described in section 2.2.2). As Part 1 consists of read sentences mainly from news websites, it exacts more careful articulation than if the speakers were to engage in natural conversation. At the same time, the speakers were paid participants and the recordings were made in the rather unnatural and formal settings of recording studios and quiet offices. Given the above setup, it will not be unreasonable to expect the participants to be speaking the ‘best’ English they could muster into the recording devices.

Hence, the term Singapore English when attributed to the English variety in Part 1 of the NSC would refer to the variety of English spoken by Singaporeans in formal situations. By usage then, it is not to be confused with Singlish. It cannot also be labelled as an educated variety since a wide range of educational levels is represented in the corpus. Consequently, the present study defines Singapore English as the formal variety (a.k.a., Standard Singapore English, for want of a better term), spoken by Singaporeans across ethnic groups, age groups and educational levels, as reflected in the NSC dataset. However, the term Standard Singapore English is avoided here because of the problems that standard language ideology entails (Lippi-Green Reference Lippi-Green2012; Milroy Reference Milroy2001).

2.3 Procedure

Annotation of each WAV file and extraction of respective formant and duration measurements were performed on Praat version 6.1.52 (Boersma & Weenink Reference Boersma and Weenink2021). Formant measurements were then normalized using Johnson’s ΔF vowel intrinsic and speaker intrinsic vocal tract length normalization method (2018; 2020). This was performed using the norm_deltaF function by Stanley (Reference Stanley2021) on F1, F2 and F3 measurements via the tidyverse set of packages (Wickham et al. Reference Wickham, Mara Averick, Winston Chang, François and Grolemund2019) in RStudio.

2.3.1 Analyzing VISC

Formant readings were taken at 15 time points between the onset and offset of each vowel. Starting at 15% after the onset and 15% before the offset to limit the coarticulatory effects of the surrounding consonants, consecutive readings were taken at 5% intervals for both monophthongs and diphthongs. Specifically, formant readings were taken at 15%, 20%, 25%, 30%, 35%, 40%, 45%, 50%, 55%, 60%, 65%, 70%, 75%, 80% and 85% of each vowel’s duration. This provides for smoother and higher resolution trajectory plots as well as better fitting of models during regression analysis. Formant trajectory charts as well as vowel trajectory charts in terms of inverse F1–F2 scatter plots were generated on RStudio using codes adapted from Stanley (Reference Stanley2018).

2.3.2 Analyzing vowel duration

Vowel duration readings were easily taken through Praat, measuring the distance between the specified onset and offset of each vowel. Building upon early works such as Fry (Reference Fry1955) and House (Reference House1961), research has long established various factors affecting vowel duration. Such factors include tongue height, vowel tenseness, postvocalic consonant voicing and manner of articulation of adjacent consonants. Factors affecting vowel duration will be discussed in section 4.3.

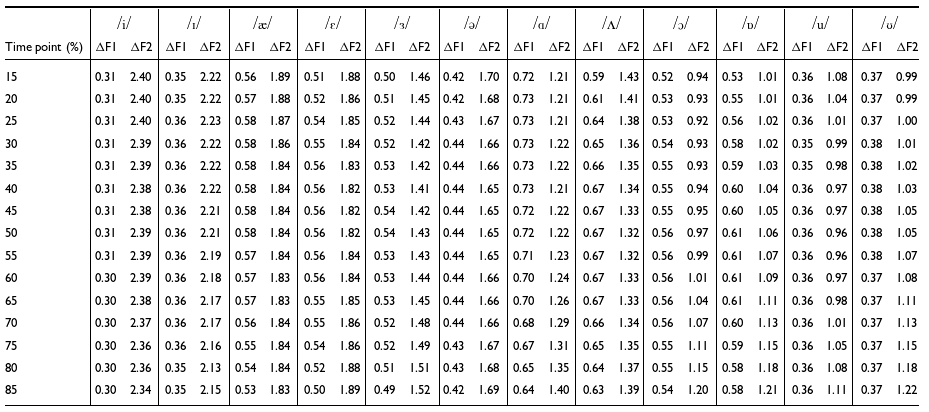

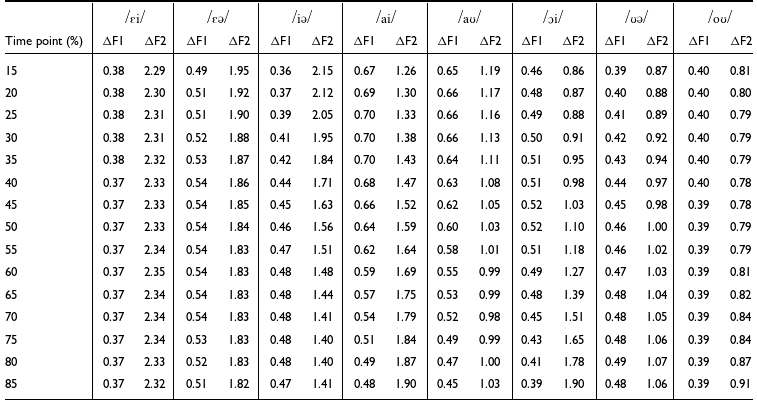

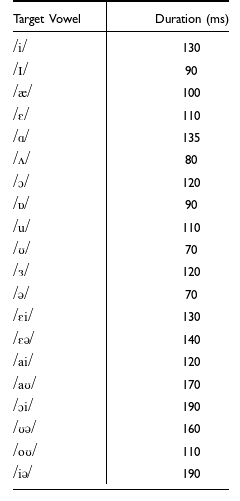

3. Results

The median normalized formant (ΔF1 and ΔF2) values measured at 15 time points between the vowel onset and offset are displayed in Tables A and B in the Appendix. The median duration measurements for each vowel are also available in Table C in the Appendix. Median values are used instead of mean values so as to eliminate any skewness caused by potential outlier values.

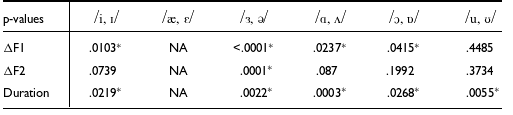

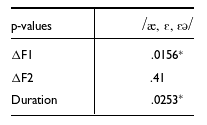

Table 8. Significance of contrasts between phonemes in each monophthong pair

Table 9. Significance of contrasts between /ɛə/ and /æ, ɛ/

3.1 Regression analysis

The 15 time point ΔF1 and ΔF2 measurements and durational values have been fitted in respective linear mixed effects models using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in RStudio. The significance of the contrasts between each phoneme in the target monophthong pairs are tested using ΔF1, ΔF2 or Duration as the dependent variable, Vowel Pair and Tenseness as fixed effects, and Speaker and Word as random effects. The following is the lmer formula used: Dependent Variable ∼ Vowel Pair * Tenseness + (1|Speaker) + (1|Word), REML=FALSE, data.

Through the emmeans pairwise test using the emmeans package (Lenth Reference Lenth2025), the contrast between the phonemes in their respective vowel pairs is tested for significance. Table 8 shows the p-values indicating the significance of the contrasts. The asterisk * is added to denote significance (p ≤ .05). As a whole, the phonemes in the target monophthong pairs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/ and /ɜ, ə/ are seen to show significant contrast in their ΔF1, ΔF2 and/or duration. No significant contrasts are seen between /æ/ and /ɛ/.

Regression analysis has also been performed on the variance in ΔF1, ΔF2 and duration among the spectrally similar vowels /æ, ɛ, ɛə/ using the lmer formula: Dependent Variable ∼ Phoneme + (1|Speaker) + (1|Word), REML=FALSE, data. The differences in ΔF1 and duration between /ɛə/ and /æ, ɛ/ have been found to be significant. Table 9 lists the p-values derived.

The significance of Vowel Type (monophthong or diphthong) for the entire vowel set has also been analyzed using the following lmer formula: Duration ∼ Vowel Type + (1|Phoneme) + (1| Speaker) + (1|Word), REML=FALSE, data. The durational contrast between the target monophthongs and diphthongs have been found to be significant (p-value = .000248).

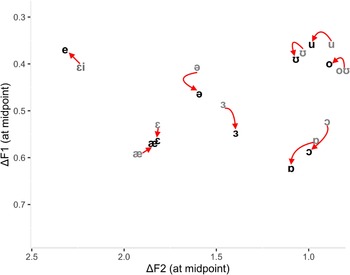

3.2 VISC of target monophthongs

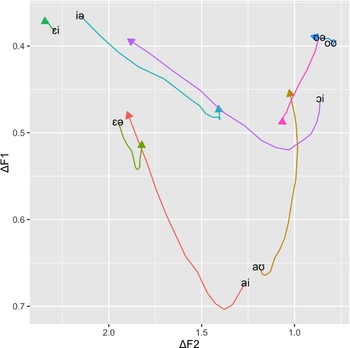

Figure 1 shows the trajectory paths of the target monophthongs visualized in an inverse F1–F2 vowel chart. Vowel labels are placed at their 15% time point position, indicating the start of each trajectory. Arrow heads are labelled at each vowel’s 85% time point position, indicating the direction and end point of the trajectory. Differences in VISC within each of the spectrally similar pairs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/ and /ɜ, ə/ are visibly apparent, with clear differences in their height and backness as reflected in the inverse F1–F2 plot, and length of trajectory. The trajectories of /æ, ɛ/ can be seen to overlap closely, as corroborated in the lack of significant differences shown in regression analysis reported in the above section, although it can be seen in Figure 1 that /æ/ begins and ends in a lower position than /ɛ/.

Figure 1. Trajectory paths of target monophthongs.

Also shown in Figure 1, the monophthongs that are lower in the vowel space, namely /æ, ɛ, ɜ, ɑ, ʌ, ɔ, ɒ/, demonstrate greater spectral change than those that are higher. In particular, the low back vowels /ɑ, ʌ, ɔ, ɒ/ show the greatest change in their trajectories. In addition, the trajectories of /u/, /ə/ and /ɛ/ show that these vowel sounds begin and end at about the same respective positions in the vowel space.

3.3 VISC of target diphthongs

Figure 2 shows the trajectory paths of the target diphthongs. /iə, ɔi, ai, aʊ/ are seen to exhibit characteristic large spectral movements that are expected of diphthongs. Compared to these, /ʊə, ɛə/ are seen to demonstrate moderate spectral change. Relative to the large and moderate movements of these diphthongs, /ɛi, oʊ/ show the least spectral change.

Figure 2. Trajectory paths of target diphthongs.

Figure 3. Trajectory paths of all target vowels.

Figure 3 shows the trajectory paths of all the target monophthongs and diphthongs visualized in the same vowel space. /ɛi/ and /oʊ/, which are seen in Figure 2 to demonstrate the least spectral change among all target diphthongs, can be seen in Figure 3 to have the minimal spectral change that is more characteristic of monophthongs of similar spectral range, namely the high front vowels /i, ɪ/ and the high back vowels /u, ʊ/. As seen in both Figures 2 and 3, /ɛi/ is realized at a much higher and more fronted tongue position compared to /ɛə/, signaling that the two do not share the same initial sound. Hence, the approximation of /ɛi/ is closer to [e] than to [ɛ]. At the same time, the brief trajectory of /oʊ/ does not indicate any upward and forward approximation towards /ʊ/ or /u/. Hence, it seems to be realized as [o].

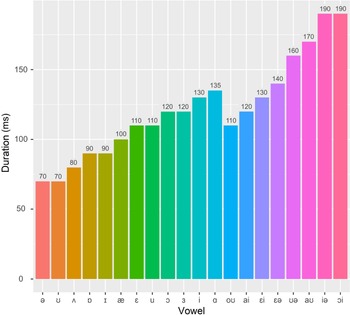

Figure 4. Ranked median duration of the target monophthongs and diphthongs.

The similarity in spectral qualities of the target diphthongal vowel /ɛə/ and the monopthongal pair /æ, ɛ/ can also be seen in Figure 3. The trajectories of /ɛə, æ, ɛ/ overlap very closely. /ɛə, ɛ/ are seen to start higher in the vowel space than /æ/, with the latter showing less spectral movement than /ɛə/ and /ɛ/, and /ɛə/ showing slightly more movement than /ɛ/ as expected of a diphthong.

3.4 Duration of target vowels

This exploratory study of the duration of Singapore English vowels is meant to complement the above VISC analysis and achieve more conclusive results. While this brief study of vowel duration helps to capture a fuller picture of the vowel system as a whole, it is not designed to fully address all possible issues that affect the length of each vowel. Nevertheless, factors that can possibly affect vowel duration will be addressed and these will be discussed in section 4.3.

Figure 4 ranks all the target monophthongs and diphthongs according to their median duration for clearer comparison. The target diphthongs /ɛə, ʊə, aʊ, ɔi, iə/ have the longest duration among all the vowels under scrutiny. /ɛə/, being one of these five longest diphthongs, is clearly longer in duration than its spectrally similar monophthong pair /ɛ, æ/. /oʊ/ is clearly the shortest among the target diphthongs and is even shorter than the monophthongs /ɔ, ɜ, i, ɑ/.

The target diphthongs are generally longer than the target monophthongs, with the exception of /oʊ, ai, ɛi/. Both /ɛi/ and /oʊ/ have the exact same duration as their respective spectrally similar longer monophthong counterparts /i/ and /u/.

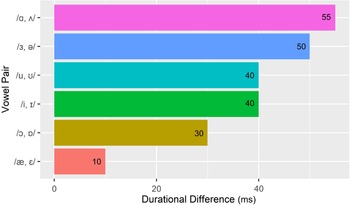

Figure 5 shows noticeable contrast in the duration of the target monophthongal pairs. The target tense vowels /i, u, ɔ, ɑ, ɜ/ are longer than their supposed lax counterparts /ɪ, ʊ, ɒ, ʌ, ə/ by an average of 44 milliseconds. /æ/ and /ɛ/, both being lax vowels, demonstrate the least difference in duration in comparison with the rest of the spectrally similar target monophthong pairs. In terms of duration, /æ/ and /ɛ/ are the most similar among all the monophthong pairs.

Figure 5. Ranked durational differences of each target monophthong pair.

4. Discussion

Having analyzed the vowels from the NSC dataset in terms of their VISC and duration, key observations are summarized below.

4.1 Target monophthongs

From VISC and duration analyses, the monophthongs in each spectrally similar pair, /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/ and /ɜ, ə/, are clearly seen to be realized as distinct vowel sounds, with the tense-lax vowel contrast within each pair found to be statistically significant either in ΔF1 and ΔF2 measurements and/or durational values. Only /æ/ and /ɛ/ are observed to have the greatest spectral overlap and closest durational values; specifically, no significant contrast can be found. Hence, from this study, it can be observed that unlike what the multiple past descriptions have concluded, there is no clear conflation of the monophthongs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/ and /ɜ, ə/ in Singapore English as represented in the NSC dataset. The only conflation that can be seen are between /æ/ and /ɛ/.

4.2 Target diphthongs

In the VISC analysis of the target vowel set, /iə, ɔi, ai, aʊ/ are clearly seen to demonstrate the large spectral change that is characteristic of diphthongs. In addition, /ɛə, ʊə, aʊ, ɔi, iə/ are the longest vowels in the set. Considering the results of VISC and durational analyses concurrently, it can be established that /iə, ɔi, ai, aʊ, ɛə, ʊə/ are realized as diphthongs by the speakers in the selected NSC dataset.

The high front target diphthong /ɛi/ and its high back counterpart /oʊ/ are clearly seen in VISC analysis to demonstrate little spectral change. This limited spectral change is found to be similar to those of their corresponding spectrally similar monophthong pairs /i, ɪ/ and /u, ʊ/. Moreover, /ɛi/ and /oʊ/ are among the shortest of the target diphthongs and have the exact same respective durations as their longer monophthong counterparts /i/ and /u/. As examined through their trajectories, /ɛi/ and /oʊ/ are seen to be approximated as the monophthong sounds [e] and [o] respectively, with their heights closer to /i, ɪ/ and /u, ʊ/ in the vowel space. This observation of the monophthongization of /ɛi/ and /oʊ/ falls in line with previous descriptions of Singapore English vowels, as spelled out in section 1.1.

4.3 Factors affecting duration

While the above exploration of vowel duration offers essential evidence to help with the evaluation of the vowels in the NSC dataset, it must be noted that there are various factors that can affect vowel duration. These have long been established by early works which are still very much cited today. For example, it is well established knowledge that vowels in lexically stressed syllables have a longer duration (Fry Reference Fry1955; Reference Fry1958; Morton & Jassem Reference Morton and Jassem1965). Peterson & Lehiste (Reference Peterson and Lehiste1960) and House (Reference House1961) also provide concurring observations that vowels have their own intrinsic duration. House further notes that tense vowels are inherently longer than lax vowels and a secondary influence to that is tongue height; low vowels are inherently longer than high vowels.

There is also the vowel lengthening effect of postvocalic voiced consonants while at the same time vowels preceding fricatives are generally longer than those preceding stops (House & Fairbanks Reference House and Fairbanks1953; House Reference House1961). Other factors include the vowel-shortening effect of additional suffix syllables (Lehiste Reference Lehiste1972; Klatt Reference Klatt1973) and the increase in duration when vowels occur in phrase final position (Oller Reference Oller1973; Klatt Reference Klatt1975; Berkovits Reference Berkovits1984).

Most of the early works on the determinants of vowel duration are based on variants of American English or highly controlled experimental studies, with later studies by others testing these predictive models on other varieties of English and other languages. A covariance structure model approach used by Erickson (Reference Erickson2000) to examine the effects of the above factors concluded that the strongest effect was intrinsic duration, with lexical stress being the second strongest predictor and postvocalic consonant voicing a significant effect but not a strong predictor of vowel duration. Meanwhile, position in a word and phrase-final position are found to have a small to moderate effect.

The vowels from the NSC dataset have been examined with the above factors in mind. The monophthongs and diphthongs do indeed demonstrate some system of intrinsic duration. Diphthongs in this dataset are indeed longer than monophthongs in general and the diphthongs that are monophthong-like are shorter in duration. It is also true that tense monophthong vowels are found to be longer than lax ones. This observation of intrinsic duration has been corroborated by the results of regression analysis, as reported in section 3.1. The durational contrast between the monophthongs and diphthongs has indeed been found to be significant and tenseness indeed correlates with durational differences within the affected monophthong pairs. However, the same cannot be said of low vowels being inherently longer than high vowels. There is no clear indication of this trend in the data. There is also no compelling durational pattern between vowels preceding voiced and voiceless final consonants. However, it is noted that vowels preceding stops are generally shorter than those preceding fricatives and affricates.

As the selected words are monosyllabic content words, possible disparity caused by stressed and unstressed syllables is circumvented. In the case of the schwa /ə/, bisyllabic words have been selected in an effort to avoid function words. However, as Singapore English is widely claimed as syllable-timed rather than stressed-timed (e.g. Tongue Reference Tongue1979:38; Platt & Weber Reference Platt and Weber1980:57; Tay Reference Tay1982:135) and substantiated by Low et al. (Reference Low, Grabe and Nolan2000) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2001), lexical stress or the lack of it in the case of syllables with a schwa /ə/ nucleus may not have such a strong effect on vowel duration.

Because the words in the dataset have been selected to provide an overall description of the vowel system of Singapore English and facilitate in-depth investigation into variations along social divides (as summarized in section 1.2), they are not designed to test the possible effects of additional suffix syllables and word positioning on vowel duration. At the same time, these are shown to have only small to moderate effects (Erickson Reference Erickson2000).

Figure 6. Duration of all /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ words.

However, as it was not possible to avoid words with r in postvocalic position in their spelling in the selected wordlist, there is the possibility of rhoticity affecting vowel duration in the words court, force and heart, and also hurt, nurse, third, beer, cheer, near, chair, scare, shared, poor and tour, despite Singapore English being generally known as a non-rhotic variety. Although investigations by Tan (Reference Tan2012; Reference Tan, Hashim, Leitner and Wolf2016) and Kwek (Reference Kwek2017) have shown that rhoticity is still an emergent feature of low occurrence, and although cursory checks were carried out during the annotation stage on Praat to ensure there were no extreme cases of the postvocalic r, the possibility of r-colored vowels cannot be totally dismissed, especially in the cases of court, force and heart where the other words in the set (i.e. pass, path and thought) do not contain a postvocalic r in the spelling.

The duration plots of all /ɑ/ and /ɔ/ words in this study are featured in Figure 6. As seen in these plots, the durations of heart and court, which are open to the possibility of rhoticity, are actually shorter or equally short in duration compared to the other vowels in the set. Figure 6 also reflects a tendency for vowels preceding stops to be generally shorter than those preceding fricatives (an observation mentioned earlier in this section). In the case of force being the longest in the set, the possible reason may be its fricative ending, compared to stops in both court and thought. Judging from this comparison, the risk of r-colored vowels affecting durational considerations in this study is not consequential.

5. Conclusion

Previous descriptions of Singapore English, namely Gupta (Reference Gupta1994), Bao (Reference Bao1998), Lim (Reference Lim and Lim2004), Wee (Reference Wee, Bernd Kortmann, Mesthrie, Schneider and Upton2004), Low & Brown (Reference Low and Brown2005) and Deterding (Reference Deterding2007), have generally converged on the observations that target monophthong pairs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/, /æ, ɛ/ and /ɜ, ə/ are realized as single vowel sounds. They have also concurred in general on the monophthongization of /ɛɪ/, /ɛə/ and /oʊ/. Having examined the VISC and duration of Singapore English vowels as represented in the NSC dataset, the monophthongs /i, ɪ/, /u, ʊ/, /ɔ, ɒ/, /ɑ, ʌ/ and /ɜ, ə/ are seen to be realized as distinct vowel sounds. However, /æ, ɛ/ have been observed to be realized without significant contrast between them. With regards to diphthongs, the NSC vowel set shows the reduction of /ɛɪ/ and /oʊ/ to [e] and [o] respectively, but not the reduction of /ɛə/.

Although there are differences reported in this paper compared to observations in past studies, they should not be attributed to language change even though the past studies referenced have a time difference of more than 18 years from the present study. As laid out in this paper’s introduction, there is now considerable evidence that spectral change is an essential part of the vowel system, even in monophthongs. Also as explained, some of the previous descriptions of Singapore English vowels were impressionistic in nature, while the acoustic-based studies relied on the widely used method of steady state analysis of vowel quality. In conjunction with using VISC analysis in the present study, the added vowel duration analysis provided a more complete representation of each vowel’s sound quality. With the adoption of more current methods and a combination of analytical tools, it is no surprise that there are differences in the vowel behavior observed. Rationally, the description reported here should only be taken as an update based on the additional analytical methods used and not to be mistaken for a demonstration of sound change in Singapore English.

On the note of sound change, apparent time change would be a more established and exact method of study. In the larger sociophonetic study performed by the author (mentioned in section 1.2) using the same dataset reported in this paper, variation by speakers’ age groups have been traced to demonstrate vowel shift in Singapore English. Comparing the vowel sounds produced by speakers from 18 to 69 years old, patterns in the vowel shift were noted. A representation of the model is reproduced in Figure 7. The vowels in grey denote the sounds produced by the older speakers, while the vowels in black denote those produced by the younger speakers, with the arrows indicating the general direction of change.Footnote 1

Figure 7. A representation of vowel shift in Singapore English based on C. Low (Reference Low2023).

While the exploration of vowel duration reported in this paper has demonstrated the presence of intrinsic duration, with diphthongs indeed longer than monophthongs and tense monophthongs indeed longer than lax ones, an area for further exploration would be to tease out different constraints on vowel duration in Singapore English. While established known constraints on vowel duration are based on highly controlled experimental studies or studies on variants of American English, some of which have been discussed in section 4.3, a study with data expressly collected to accommodate the different consonantal constraints can help to validate if the same vowel durational constraints reported in section 4.3 are found in Singapore English. As evidenced in the Scottish Vowel Length Rule (Aitken Reference Aitken, Benskin and Samuels1981), different varieties of English may exhibit different vowel durational patterns. A deeper exploration of the vowel durational patterns of Singapore English will further validate or substantiate the results of the present study.

Appendix

Table A. Median normalized formant values of target monophthongs at 15 time points

Table B. Median normalized formant values of target diphthongs at 15 time points

Table C. Median duration of all target vowels