Introduction

In the Prelude to his groundbreaking biography, Gabriel Fauré: A Musical Life (translated by Roger Nichols), Jean-Michel Nectoux begins with the extraordinary question that was often posed to him, ‘Why Fauré?’Footnote 1 His extensive archival research recovered unpublished works and filled in missing or incomplete accounts left open because of what he described as a widespread assessment of Fauré as a ‘marginal or minor composer’.Footnote 2 The biography makes a deeply personal, musically sensitive, and compelling case for reassessment of Fauré’s compositional output which I would enthusiastically recommend to anyone wanting to deepen their relationship with his music, as I assume avid listeners of this reviewed album may wish to do.

Nectoux’s assessment of Fauré both anticipated and continues to stimulate the admiration of contemporary connoisseurs championing performances of the composer’s work beyond the tradition of individual works that have been continuously performed, like his many fine art songs, the first violin sonata, and the Élégie, Op. 40, for cello and piano. The urgency for a reassessment of the composer’s broader output is further evidenced by a tendency for Fauré’s music to be the subject of Francophile collected works projects which includes the current volume Horizons II, continuing a recording project featuring the composer’s instrumental chamber music that began in 2018 with Horizons, an album including recordings of both violin sonatas, both cello sonatas, the piano trio, a number of works for solo strings with piano, art songs, and solo piano works.Footnote 3

Horizons II

The second installment of this recording project, Horizons II, in three compact discs, includes the hallmark gems of Fauré’s late instrumental chamber music: full recordings of both the Piano Quartet no. 1 in C minor, Op. 15, (N 48; 1879, rev. 1883) and Piano Quartet no. 2 in G minor, Op. 45 (N 9; 1886); both the Piano Quintet no. 1 in D minor, Op. 89, (N 158; 1887–1905) and the Piano Quintet no. 2 in C minor, Op. 115, (N 188; 1919–1921); the String Quartet in E minor, op. 121, (N 195; 1923–24) and the Serenade for piano and cello, Op. 98, (N 169; 1908).Footnote 4 The album’s supplementary CD booklet and jacket playfully express the spirit of this recording project, which features members of the ensemble in opulent sartorial stylings typical of the Roaring 1920s, inviting the listener into the social milieu of period salon performance patrons. The CD booklet features short essays by acclaimed American jazz pianist Brad Mehldau, French musicologist Iréne Mejia Buttin, and a coquettish short story by Guy de Maupassant, ‘La moustache’, providing a sense of provocative salon entertainment set against the horrors of the first World War and suggesting the mustache (which Fauré often wore) as a metonym for the period’s essential French sensibility. While Brad Mehldau – who in May 2024 recorded and released an album honouring the composer, called Après Fauré – remarks on the dreamy harmonic soundscapes he sees influencing his own practice among a century of jazz music, Iréne Mejia Buttin locates Fauré’s turn to chamber music in relationship to the 1871 founding of the Société Nationale de Musique and as an essential part of the development of his late musical style.Footnote 5

Fauré’s quintessential chamber music begins with the composition of his first violin sonata (1875–76) and piano quartet (1876–83), both composed in his early thirties. The composer’s two piano quartets and quintets form much of his compositional output in this genre (and in this recording) which is not surprising given that the composer frequently performed the works himself on the piano, often accompanied by one of his favourite chamber music partners, the virtuoso violinist and accomplished composer Eugène Ysaÿe (1858–1931). Fauré’s intimate familiarity with these ensemble forces puts his piano chamber works in clear relationship to archetypes of the compositional medium such as the two quartets by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart K. 478 and K. 493 and the quartet and quintet by Robert Schumann, Opp. 44 and 47. The hallmark of their compositional effectiveness – and a significant interpretative necessity in performance – is in the ability to both balance the sonic mass of the piano against the combined string ensemble and to spread engaging melodic material across the ensemble to create extraordinary textures and facilitate meaningful conversational interactions.Footnote 6 The performances featured on this disc of Simon Zaoui’s sparkling pianism matched with strings led by the expressive and visionary violin playing of Pierre Fouchenneret joined by Raphaël Merlin (vc), Marie Chilemme (vla), and Quatour Strada are filled with fiery energy and sensitive, balanced phrasing that draw the listener into Fauré’s intimate musical world.

Listening to a piano quartet or quintet I alternate between imagining the agency of the individual pianist balanced against the social unit of the blended string ensemble – as in the first movement’s opening theme of the Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, where the unison string theme is first accompanied by (bar 1), then commented on (bar 8), and finally overtaken by the piano (bar 14) – and focusing my attention on melodic voices expressed by individual string instruments or expressed in the left or right hands of the piano – such as in the subordinate theme of the same movement beginning in bar 38 with the warm and sensitive viola tone of Marie Chilemme traded in canon across the ensemble. While the conventional challenge to a string player in this format is to understand the nature of their role, when to blend and when to project, the pianist’s challenge is considerably more complex, requiring some technical and musical listening skill outside that of typical solo piano playing. The pianist develops a sense of how to open registral space to make room for string melodies to project – as in the ethereal beginning of the Piano Quintet No. 1 in D minor where Simon Zaoui’s arpeggios create a breathtaking atmosphere, or the earthy beginning of the Piano Quintet No. 2, where the shared lower register and activity of the piano makes projection for the first thematic entrance a significant challenge for the solo viola – as well as to sing pianistic melodic and bass lines so that they can match the focus and clarity that a string instrument may imbue into a cantabile melodic line, such as Simon Zaoui does magically at the beginning of the development in the first movement of the Piano Quartet No. 1 in C minor, soaring over hushed, sustained string harmonies like a Chopin nocturne.

Typical coaching I have received and passed on to student pianists to learn to be effective chamber musicians is to rely less on the sustain pedal than in solo playing, allowing the sustained string sounds to fill out the ensemble, lightening accompanimental textures especially in middle registers that overlap with string melodies and expressively projecting pianistic melodic lines in the outer edges of the piano voice while applying finger pedalling techniques to create singing bass lines and upper melodies. This advice is particularly apt in performance of Fauré’s music given contemporary accounts of his playing: Marguerite Long described his touch as ‘supple’ and ‘heavy’ to produce a ‘beautifully rounded sonority’, and remarked that his most frequent comments were ‘Nuances without changing speed’, and ‘Let’s hear the bass!’; Alfred Cortot expressed surprise that a ‘sensitive poet [like Fauré] would be such a dry pianist’ and that he ‘never used the pedals’.Footnote 7 Fauré’s chamber works are exemplars of the piano chamber music tradition but also pose unique interpretative challenges given his increasing attention devoted to complex contrapuntal textures, a pervasive lyrical impulse and especially interest in linear, melodic bass lines that eventually became hallmarks of his ‘third period’ compositional style as described by Nectoux.Footnote 8

The recordings featured in this collection are a remarkable testament to the blend of lyricism and understated virtuosity that characterizes Fauré’s chamber music. Each of the hallmark inner Adagio and Andante movements of these works sing with opulent expressivity across the ensembles, and the Scherzo from the first piano quartet as well as Allegro vivo from the second piano quintet practically leap out of the recording with enthusiasm and energy. As a virtuoso pianist himself, Fauré was unsurprisingly quite discerning in his assessment of performances of his work by others, notably criticizing performances of many other contemporary professionals, including Lucien Capet of Quatuor Capet whom he characterized as being ‘an admirable Beethoven player’ but missing the mark in a performance of the D minor Piano Quintet Op. 89.Footnote 9 While Fauré’s relationship to pianist Marguerite Long changed over time, his early endorsement of her pianistic interpretations and the ownership she often claimed over his performance style make her historical recordings of Fauré’s chamber music an interesting benchmark for gauging the spirit of the composer’s pianistic lyricism in this context.

The recording style as a whole is highly polished, and microphone placement feels very close and dry with minimal reverb added, creating a feeling for the listener of being intimately involved in the space of the performing group, or in a small salon room. As opposed to a common unfortunate tendency for a large concert grand piano to overwhelm string parts, in this recording the mix is weighted significantly towards the strings – and particularly the first violin among the strings – which provides an unusual and highly textured perspective on these chamber works not typically representative of a concert hall experience. As a listener I feel somewhat like I am standing three feet from Pierre Fouchenneret, which is an extraordinary listening perspective for these works not often experienced by listeners outside the ensemble. This intimate perspective unfortunately may be an overcorrection of the challenges posed by the natural sonic presence of the piano, and results in some virtuosic passage work and cantabile lines given to the piano feeling backgrounded or accompanimental to secondary voices outlined in the strings.

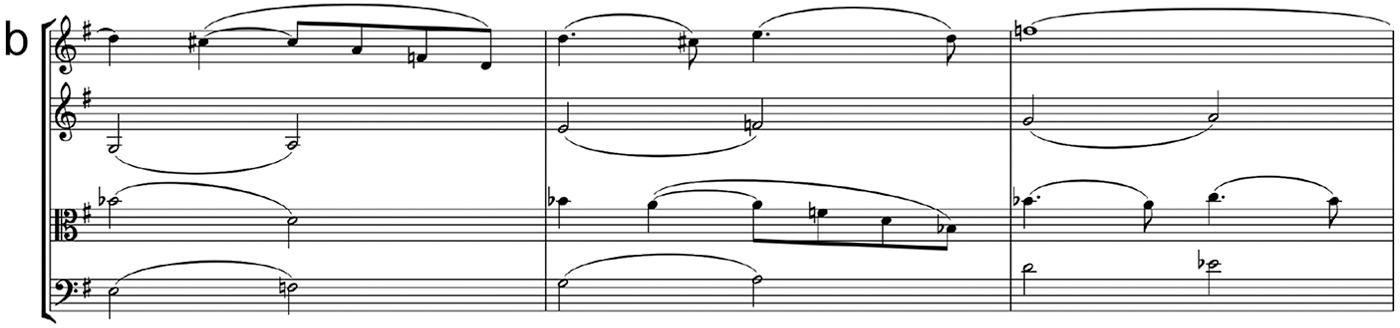

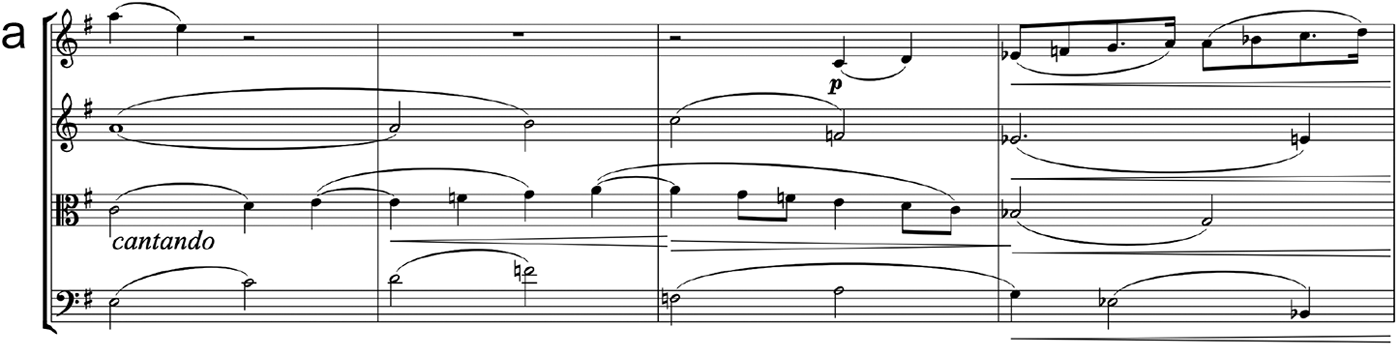

In the sparkling scherzo Allegro vivo of the second piano quintet, Op. 115, pianist Simon Zauoi’s virtuosic capabilities are on full display accompanied by Quatuor Strada, set against lyrical melodies such as the first violin’s cantando beginning in bar 41. However, when the piano is given the same cantando melody in bar 65, the imitative responses in the strings are significantly more present in the balance, reducing the listener’s ability to focus on the continuity of the pianist’s melody that transforms into the extraordinary lyricism of the melody in bar 77 and retransition to the running semiquavers in bar 91. In the Op. 89 piano quintet there is a similar balance issue in the Adagio’s interior theme beginning at bar 47: the piano begins a melody marked dolce cantabile followed by the viola marked dolce in close canon, but the recording mix suggests that the viola part is primary. When the violin answers five bars later with the same melody and the cello in canon and again in forte at bar 61, this same melody is clearly the primary line. In the opening Allegro molto of the Op. 45 piano quartet, the strings present the main theme in fortissimo octaves against churning demisemiquavers in the piano, but as the piano takes the melody over in the transition to the second group at bar 11, in this recording the sound of the strings continues to dominate even as their role is properly countermelody. Similarly for the final thematic statement in the lowest register of the piano seven bars before the movement’s end: while each sustained note receives accents in low octaves, the pianissimo chromatic line in the first violin dominates the recorded texture. The 1940 recording made by Marguerite Long, Jacque Thibaud, Maurice Vieux, and Pierre Fournier by contrast draws the listener’s ear clearly to primary thematic material both in performance execution and mixing, though it lacks the same textural clarity afforded by the close microphone techniques used in this collection’s modern recording style.

Fauré’s Architecture: Model-Sequence Technique

Fauré’s compositional style is often characterized in its unique approaches to counterpoint and harmony. Another essential stylistic element, the composer’s frequent expressive use of conventional model-sequence technique, both in expected form-functional locations such as digressions and transitions and its use as a compositional and expressive principle for larger sections, provides significant interpretative insight into the architecture of his late style. Many extraordinarily expressive high points are reached through transposed repetition of contrapuntal cells, sometimes imbued with slight variations to increase tension or add colour.Footnote 10 The interpretation in this set of recordings is particularly sensitive to the intensity of musical feeling and direction that is afforded by usage of this technique, so this recording makes a good companion to listeners wanting to explore this aspect of the composer’s musical language.

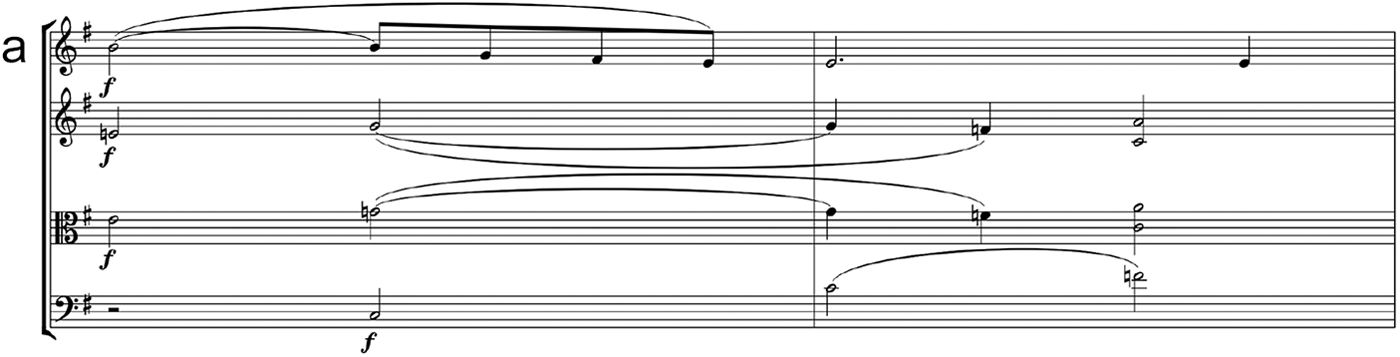

Fauré’s usage of the technique in conventional places such as digressions or transitions, such as in the digressions from the Op. 89 Adagio’s primary and interior themes, follow typical formal templates from Classical music, although often in support of slippery or disorienting harmonies. The digression of the primary theme in bars 13–17 provides a one-bar model in bar 13 that repeated precisely in bar 14 except for the last beat, which sets off a rising sequential chain transposed by minor thirds until it completes the d3–d4 octave in the bass register of the piano. The digression of the interior theme from bars 55–60 features a similar rising relationship of minor thirds driven by the cello line from A♯ in bar 55 to G♮ in bar 60, this time supporting a two-bar cell in bars 55–56 that is transposed upward a minor third in bars 57–58, followed by a new one-bar model in bar 59 that is repeated up a minor third in bar 60; this telescoping fragmentation of grouping size is used often by Fauré to increase the sense of momentum and speed without altering tempo. A danger in sequential passages like these for performers is to wander without a sense of direction or providing changing harmonic colours through the sequenced units. In this recording, both digressions are wonderfully realized by the ensemble, creating an extraordinary build in tension and anticipation towards the full-throated and dramatic return of the initial thematic material.

More extraordinary, and arguably responsible for much of the movement’s intense expressive character, is how material in the Op. 89 Adagio is subjected to extension through model-sequence technique when it returns. This is evident in returns of material at both a small and large scale and represents a compositional principle of heightened activity in subsequent parallel sections noted by Joel Lester in the music of J. S. Bach.Footnote 11 At the smaller scale, we can see this principle illustrated when material from bars 5–8 returns after the digression in bars 22–25. While bars 7–8 are a contrasting response to bars 5–6, bars 22–23 are repeated up a fifth in bars 24–5 as the line crescendos to a dramatic return of the primary theme in bar 26, this time in string quadruple octaves counterpointed by the descending scalar countermelody in the piano decorated by triplets. The closing section for this primary theme beginning in bar 30 features an extended model-sequence passage (bars 30–1 repeated up a half step in 32–3, bar 34 repeated up a half step in bar 35, bar 36 repeated up a third in bar 37 and again in bar 38) that continues the energy from the return of the primary theme until the melody from bars 1–4 is repeated in diminution in bars 39–40, providing a climactic summary to this opening section.

At a larger scale, when material from bars 5–8 returns after the interior theme, it is subjected to much more intense sequential repetition: bars 79–82 are repeated up a step in bars 83–86 connecting to the sequential digression of bars 87–92. The sequencing process continues as bars 93–94 are repeated up a step in bars 95–96 and again in bars 97–98 blending the digression and descending piano countermelody of bar 26ff into the return of theme in bar 97 in string octaves. The theme itself here is sequentially extended by two bars in bars 100 and 101 through the rising chromatic scale, leading to a 6-bar thematic statement instead of the typical 4-bar blueprint. The overall effect from bars 79 to 102 then is of continuous sequencing of thematic material to vary and intensify the original theme and is a powerful representative of Fauré’s usage of this technique for specifically expressive and intensifying effects.

That my ear is drawn towards these essential architectural characteristics of the works through these recordings shows the intimate understanding and care that the performers have taken in crafting their interpretation. Focusing on the pervasive model-sequence element of Fauré’s compositional architecture is a remarkably effective way to engage with the significant accomplishment of this recording as well as to understand the nuance of the composer’s late tonal language.

String Quartet in E minor, Op. 121

I was very pleased to hear Quatuor Strada’s fine recording of Fauré’s only string quartet, Op. 121 (N 195; 1924), in E minor, which does not experience the same difficulties in mixing as the chamber works with piano. As the last work the composer wrote while experiencing increasing hearing loss, this quartet is a remarkable document of his musical style which was undertaken with serious consideration. As Fauré wrote in a letter to his wife on 9 September 1923:

I’ve started a Quartet for strings, without piano. It’s a medium in which Beethoven was particularly active, which is enough to give all those people who are not Beethoven the jitters! Saint-Saëns was always nervous about it and didn’t try the medium until near the end of his life. He didn’t succeed as he did in other areas of composition. So you can imagine that I’m nervous in my turn. I haven’t told anyone, and shan’t until I’ve nearly finished. If people ask, ‘Are you writing anything?’ I shall say bluntly ‘No!’ So keep this to yourself.Footnote 12

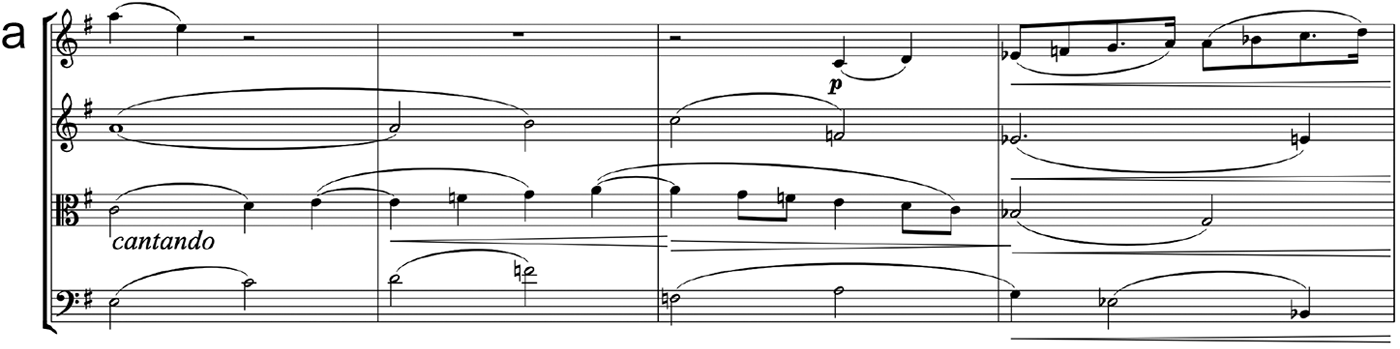

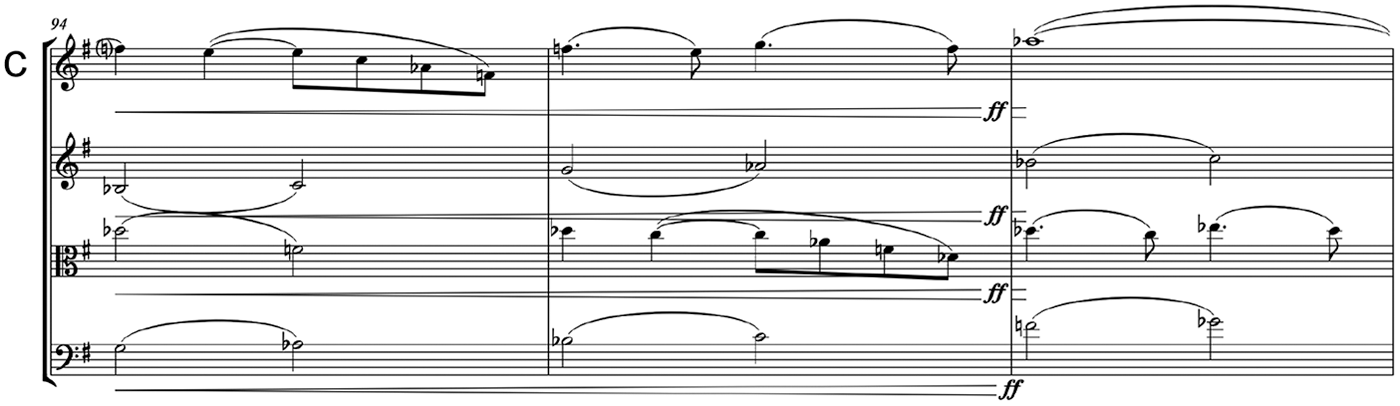

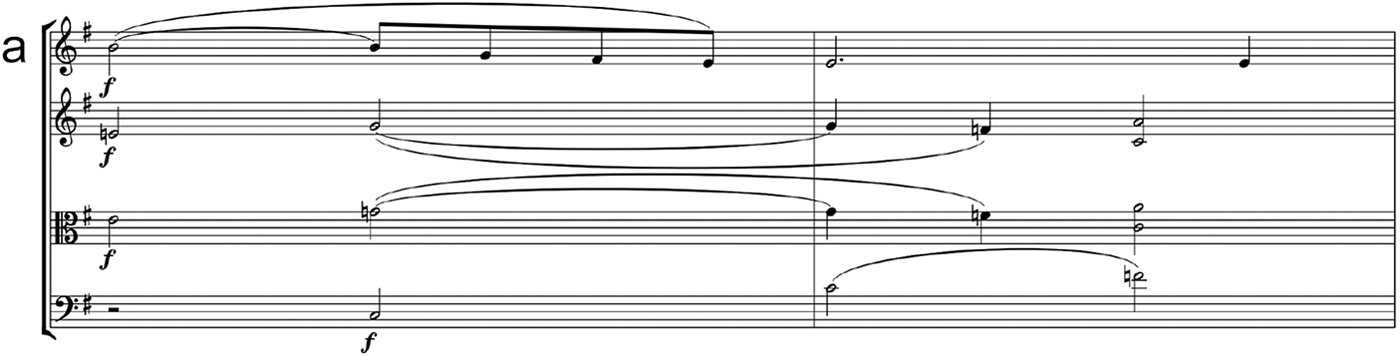

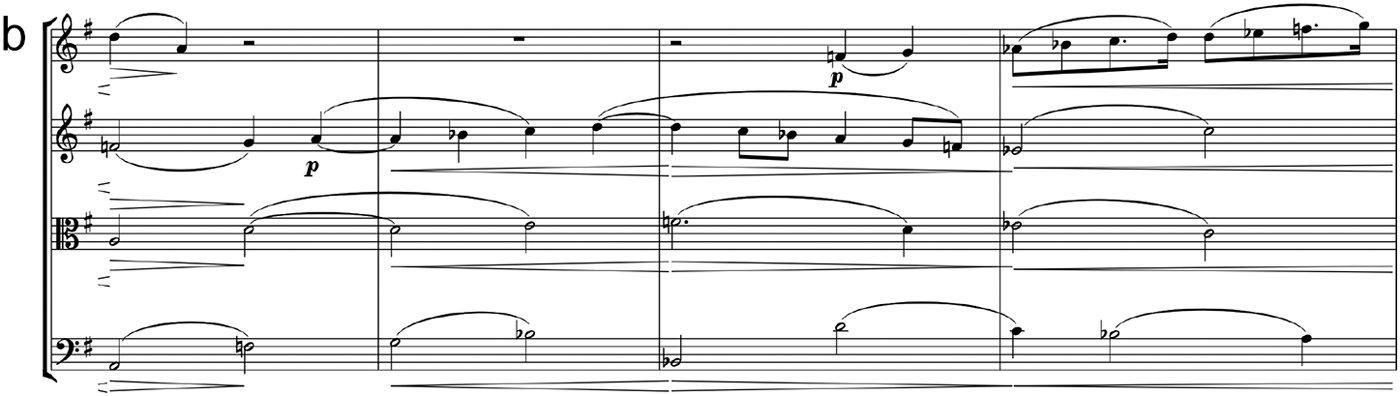

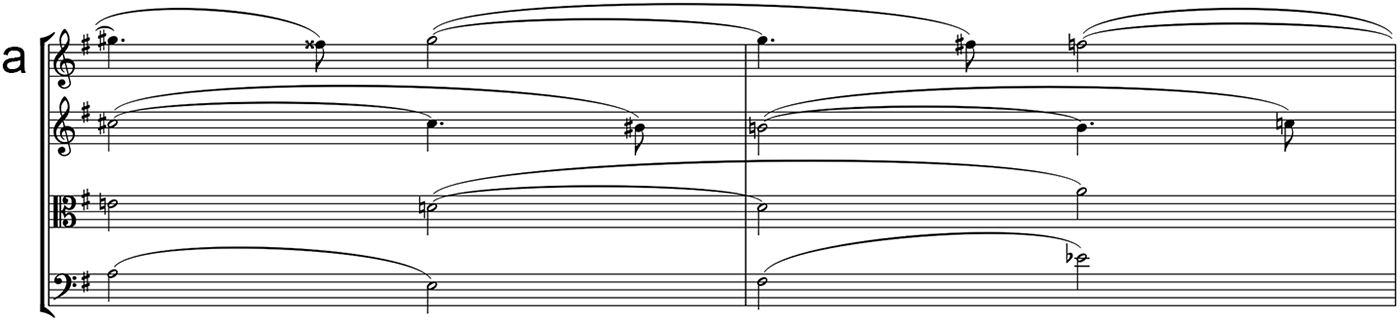

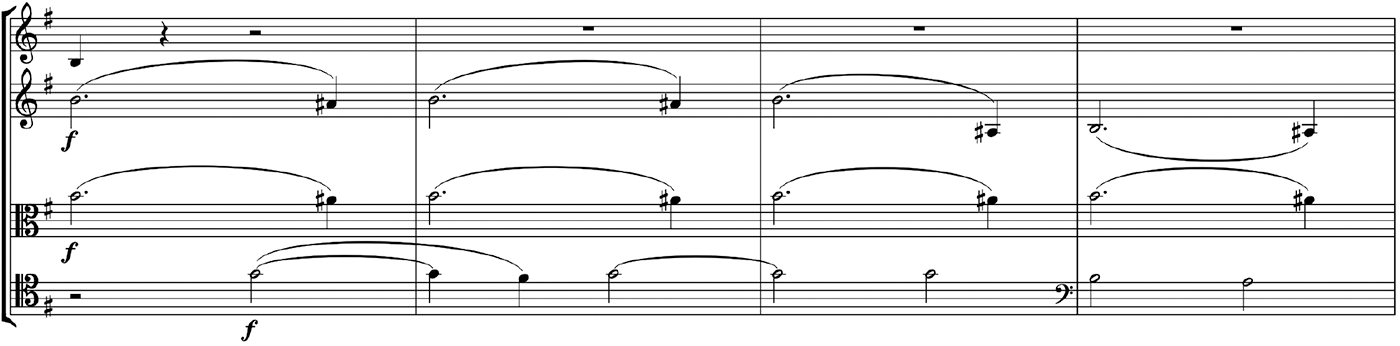

While the Andante of this quartet was the first movement to be finished, the Allegro moderato exhibits masterful clarity working in the Classical sonata-allegro form and is saturated with model-sequence technique that provides each section with direction and variety as floating contrapuntal cells are considered at different tonal levels through each section. The development of this movement in particular is remarkable over the course of 50 bars for its telescoping of the scale of sequenced units as illustrated in Examples 1–6 below while engaging with a rotational thematic structure referencing elements from the exposition.Footnote 13 The development begins with a ten-bar unit in bars 60–69 that evokes the exposition’s main theme in B minor, followed with an exact repetition returning to E minor in bars 70–79; Example 1 and following line up these sequential statements to facilitate note-to-note comparison. Because of the 10-bar length of this cell, it is easy to miss that the bars 70–79 are an exact repetition up a fourth.

Example 1a. Gabriel Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, Op. 121, mvt 1. Allegro Moderato, bars 60–69Footnote 14

Following this initial reference to the exposition’s main theme, the thematic rotation continues in Example 2 with a reference to the cantando melody of the exposition’s subordinate theme (bar 35) in a four-bar unit in bar 80–83. A quick answer referencing the first violin’s arabesque from the main theme leads to the unit repeated up a fourth in bars 84–87 with violin 2 and viola parts interchanged.

Example 1b. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 70–79

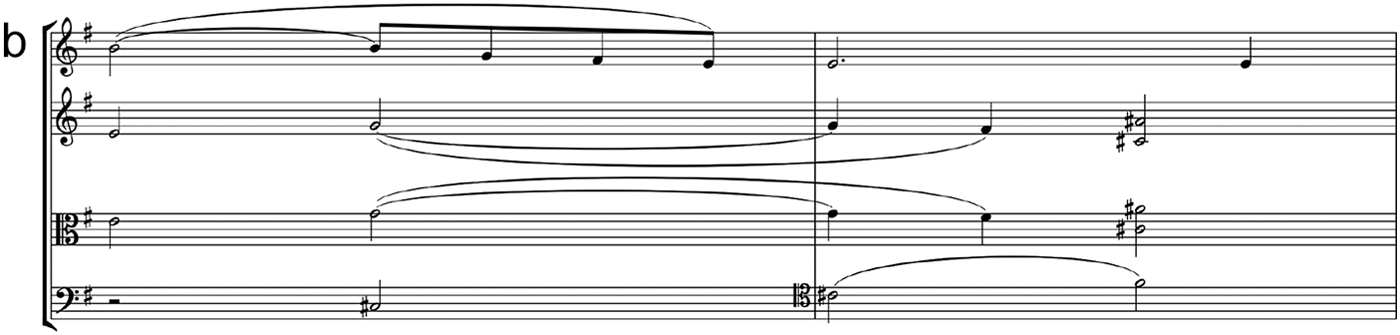

Example 2a. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 80–83

Example 2b. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 84–87

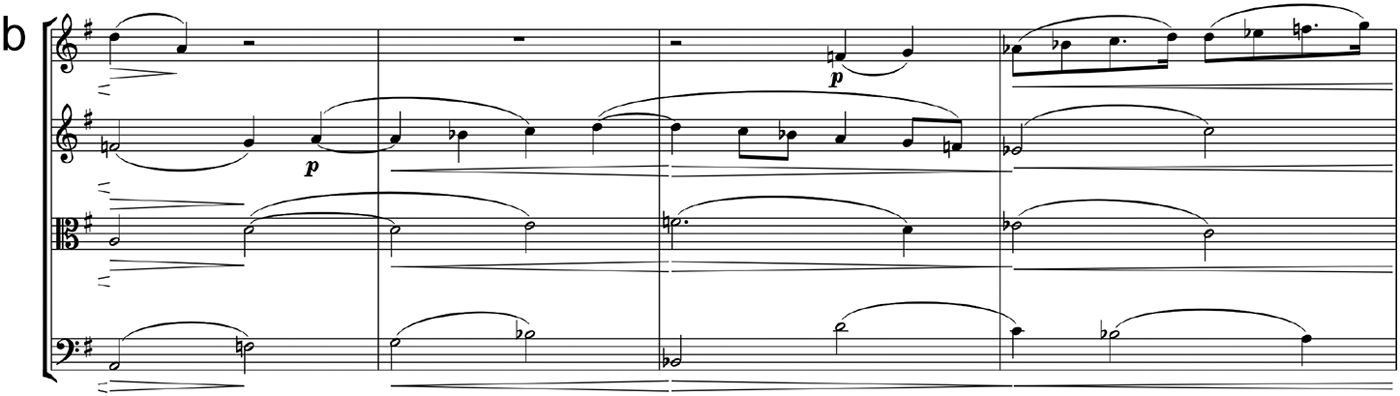

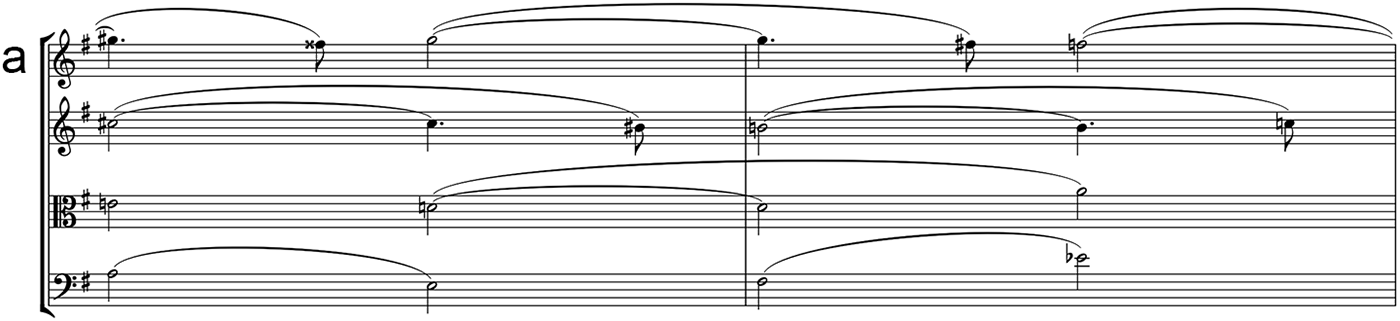

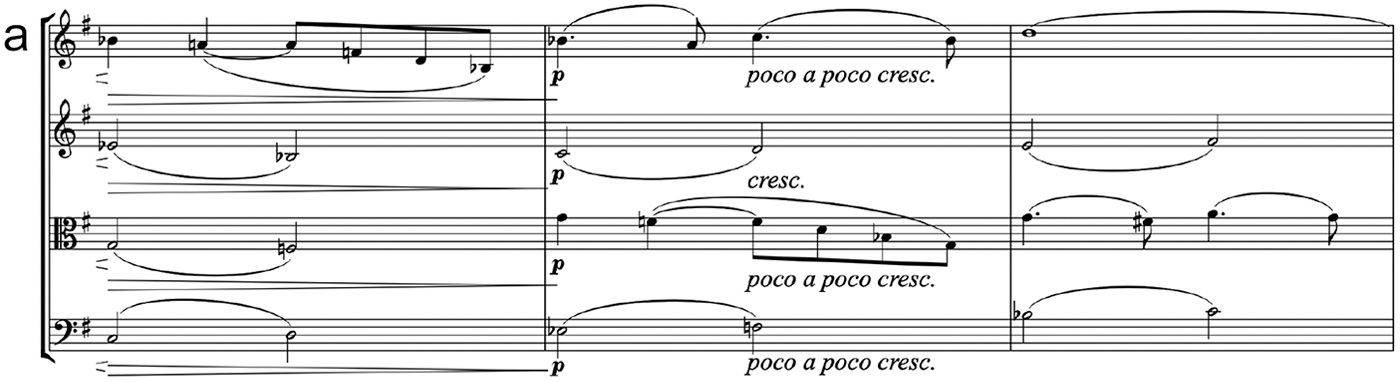

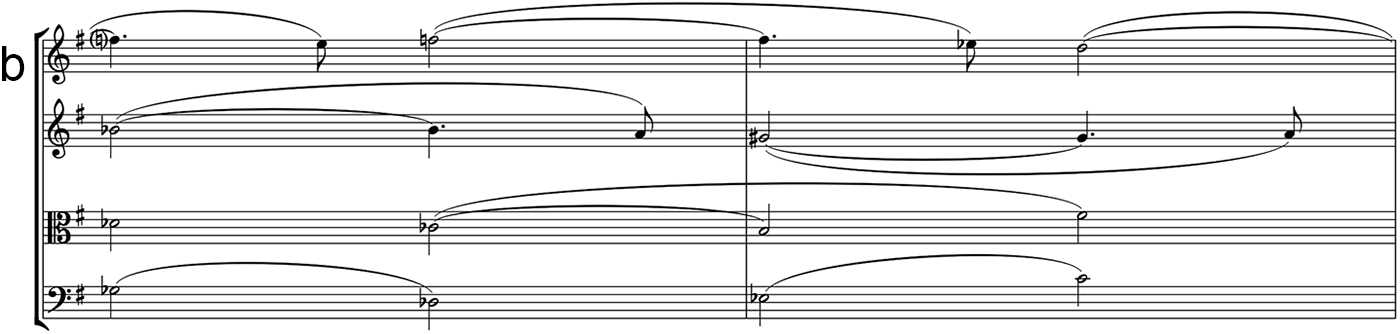

As the development’s intensity increases, the sequencing unit sizes decrease to three bars as shown in Example 3, with a descending motive in bar 80 in the first violin (with material from bars 5–6 expanded from stepwise motion to arpeggiations) answered in canonic imitation in the viola in bar 81. Each subsequent repetition is transposed up third, first a major third, and then a minor third. This differing transposition level is made possible with some slight intervallic changes evident when comparing bars 89–90 to 92–93 in Example 3.

Example 3a. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 88–90

Example 3b. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 91–93

Example 3c. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 94–96

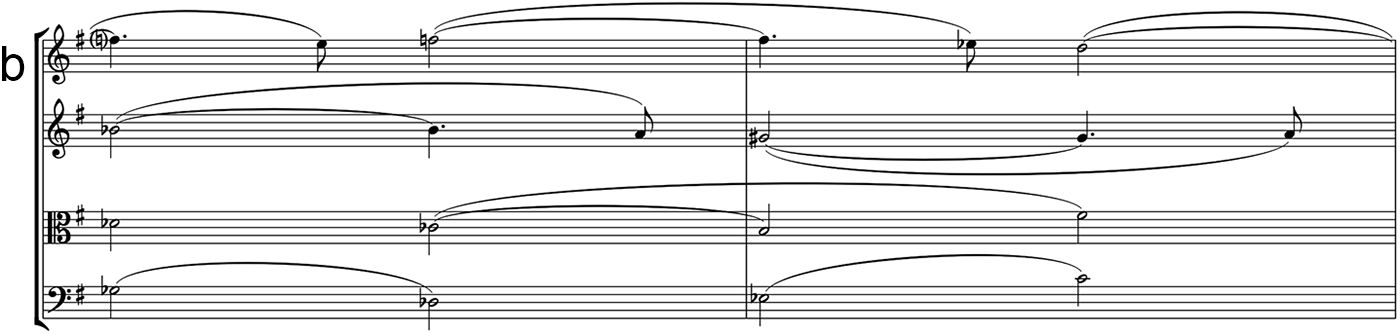

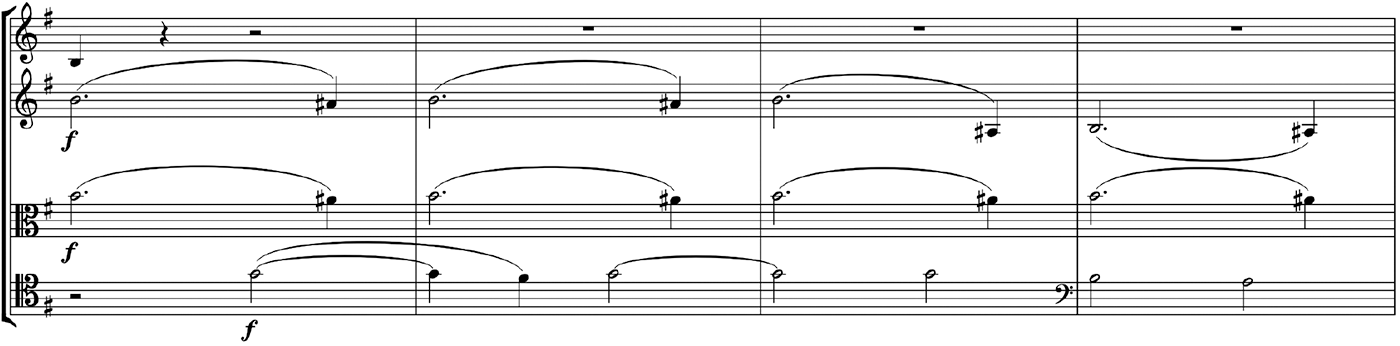

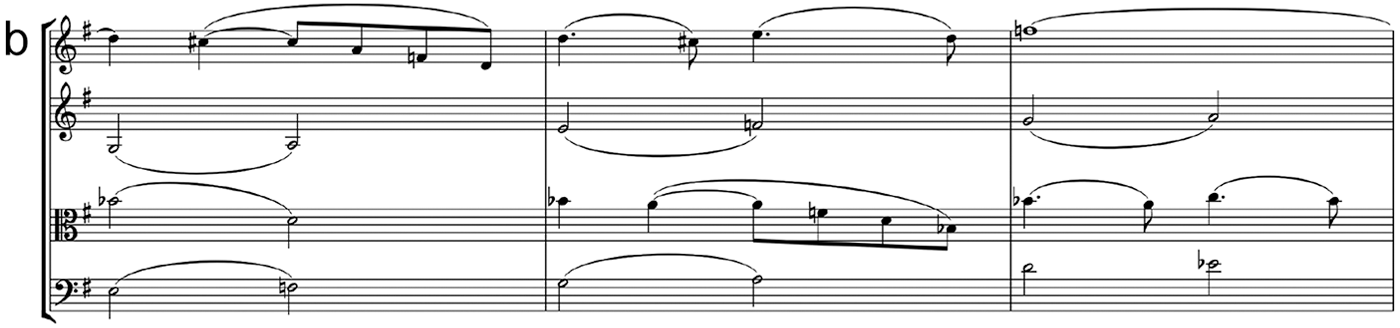

Example 4 shows the sequencing unit sizes decreasing to two bars in bars 97–102, and the transposition direction descending instead of ascending as the music deliriously spins out of control.

Example 4a. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 97–8

Example 4b. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 99–100

Example 4c. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 101–102

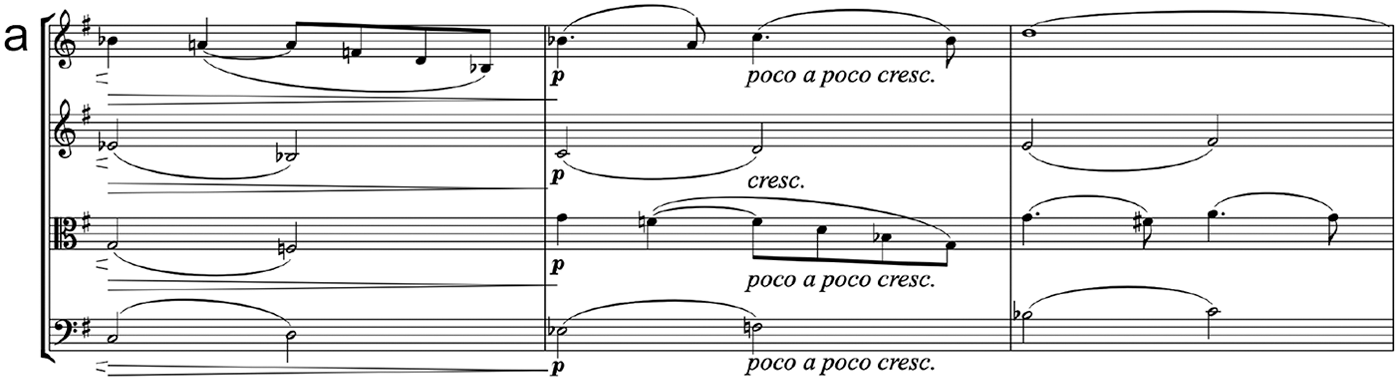

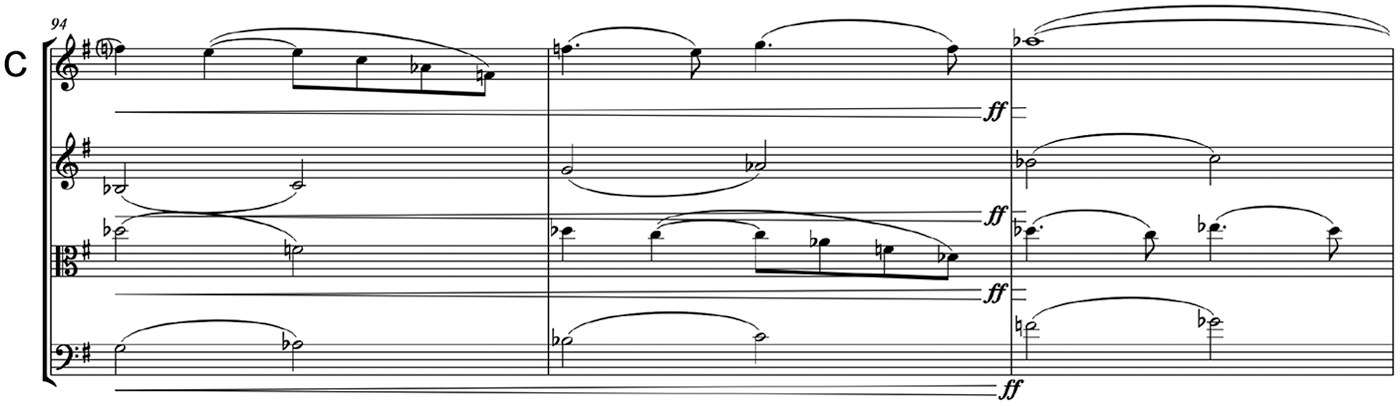

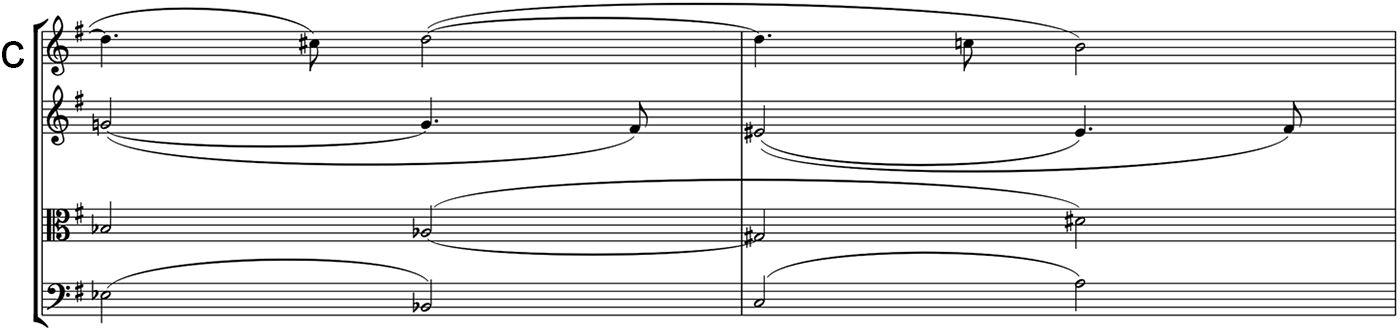

Example 5 represents the arrival of maximum intensity for this development section where an E minor harmony representing the home key reached in the first violin’s melodic line is held steady as pedal point while the harmonic support in the cello and viola is ratcheted up a half step between the two sequence units.

Example 5a. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 103–104

Example 5b. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 105–106

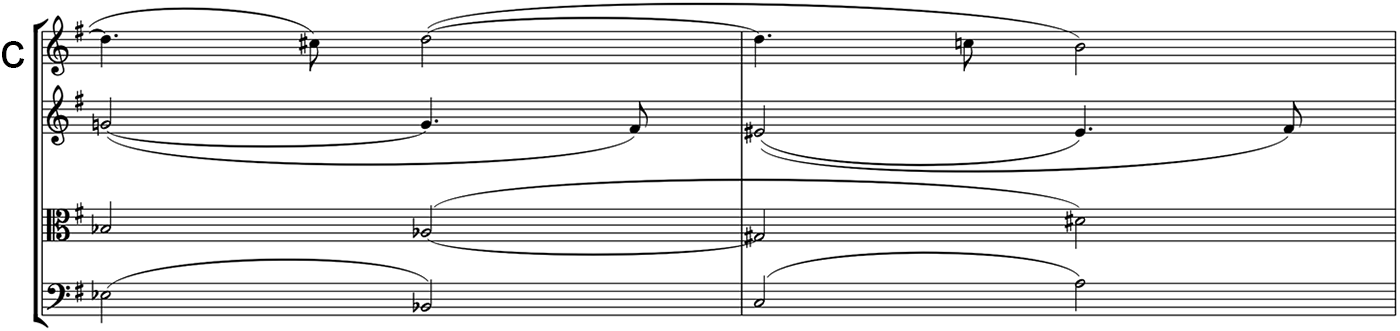

Example 6 ends the sequential process that has permeated the entire development with an arrival on a dominant pedal point articulated in all instruments but violin 1. In all, the sequential process and telescoping grouping size illustrate a tightly controlled compositional plan for this development section that compactly references materials from the exposition while heightening their expressive potential and intensely driving to the dominant preparation that ends the developmental process.

Example 6. Fauré, String Quartet in E minor, bars 107–110

The A minor Andante movement of this quartet is the emotional core of the work and holds the spark of Fauré’s inspiration to embark on writing a string quartet. The movement is beautifully rendered by Quatuor Strada and includes a quintessential sequential passage from bars 24–41 that exhibits the same principle of telescoping grouping as the music builds from a gentle rocking piano to a burning fortissimo that figuratively points over the horizon towards the future.

Conclusion

While the technique of sequential repetition has a reputation for being mechanical and repetitive, or being associated with particular form-functional processes like digressions or transitions, it is truly remarkable to hear Gabriel Fauré using this process and the power of repetition to communicate some of his most powerful emotions and provide building blocks of architecture for entire musical sections and movements in his late style. In many ways, the spirit of his contrapuntal and harmonic style finds an effective vehicle in the structure, direction and repetition offered by model-sequence technique and gives the listener a chance to wonder at his contrapuntal inventions through different transpositional levels, like turning a kaleidoscope with each musical idea. The ability of Quatuor Strada and each of the musicians in this recorded collection to take these compositional materials and bring them to life in such a compelling way is a testament to their deep passion and understanding of Fauré’s compositional language in this recording.