Human–computer interaction (HCI) and User Experience (UX) professionals can benefit from having a basic understanding of law and the legal system in the United States. Technology design significantly impacts many areas of life and work, sometimes requiring regulation and other times indirectly or more directly influencing laws and policies. Technology itself can also be designed and used to implement or enforce regulations and policies. Laws can impose requirements on some areas of technology design. For example, in design areas where user data and privacy might be involved, legal compliance and regulation can easily become a necessity. Design that impacts the securing of user information, design of health-related systems, and design of systems that interact with government services all illustrate the value that HCI and UX professionals can find in understanding U.S. law. This chapter will cover the history of U.S. law, the basic constructs of the U.S. legal system, the differences between law and policy at the federal versus state level, the use of legal resources, and how to apply basic legal principles to HCI research. It should be noted that new executive branch leadership, changes in court opinions, and new or revised legislation can have a significant impact on the legal topics discussed in this chapter.

1.1 History of the U.S. Legal Structure

The U.S. legal structure was heavily influenced by the backgrounds of the immigrants who made up the early English and European colonial population in the U.S., combined with the factors that motivated the original states to break away from England.Footnote 1 The Declaration of Independence was predicated by a restriction of freedoms and compounded by a desire to protect what were considered to be “natural” human rights, which are rooted in the philosophies of those such as John Locke, St. Thomas Aquinas, and many before them.Footnote 2 The idea of natural rights acquired by birth actually comes from a framework of natural law that, ironically, would have also influenced the legal system of England. The emergence of a new government and therefore formalized U.S. law was also influenced by the idea of “federalism,” where there exists a national (or federal) level of government as well as a state level of government in the U.S., carrying with that structure a certain amount of state government power and independence from the federal government in certain matters.Footnote 3 Similar tensions and struggles between state power and federal power that were present at the time of the original creation of the U.S. Constitution are still present today. The structure of the U.S. government in its conception also has significantly dictated the structure of U.S. law. A core aspect of that structure is the separation of powers through the executive (U.S. president and executive agencies), judicial (federal court system), and legislative (Congress) branches of government.Footnote 4 As such, the U.S. Constitution established the basis for legislative power for creating laws, the executive power to veto legislation and enforce laws, and the judicial power afforded by the creation of the U.S. Supreme Court and lower federal courts. This government design was intended to balance out the power of the U.S. federal government.Footnote 5

1.1.1 Basis for U.S. Law

Civil law is law that is based primarily on laws that have been codified through enacted legislation, while common law is derived primarily from prior judicial rulings and precedent.Footnote 6 Many legal traditions and inherent assumptions on legal basics come from common law tradition and precedent that has evolved over almost 1,000 years, dating back to the early royal judges in England. By the time of the Declaration of Independence, the traditions of English common law were well established in various forms throughout the North American colonies.Footnote 7 While this resulted in a legal tradition that in general is common law, there are a number of aspects of U.S. law that have been codified through constitutions, statutes, international treaties, court rules, and the regulations from administrative agencies at both the federal and state levels.Footnote 8

1.1.2 The U.S. “Adversarial” System of Law

At the international level, many countries follow an “inquisitorial” system of law, which means that the judge can ask questions and call witnesses, rather than the attorneys.Footnote 9 In the U.S., there is an “adversarial” system of law which has as one of its hallmarks a neutral decision-making party to passively decide the case and two opposing parties who present arguments and evidence, with equal opportunity to argue their case before the passive party, which would be the judge and sometimes a jury.Footnote 10 It is believed to be essential that the primary decision-maker (judge) does not actively gather evidence and engage in the arguments but rather has a more passive role in evaluating the evidence. This type of legal structure is considered to be “adversarial” because there is an opposing clash of conflicting arguments and evidence by both sides of the case (plaintiff and defendant). A jury is a common component of the adversarial system because it is another passive component (like the judge) without prior knowledge of the facts and not actively engaged in the investigation or questioning process.Footnote 11 For criminal cases where the criminal charge has a potential for incarceration for six months or longer, the Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides a right to a trial by jury.Footnote 12 For lesser crimes, a trial by jury is not required; however, some states (e.g., Virginia) provide the right to a trial by jury in all cases – with the caveat that the plaintiff has to pay for the costs if they lose the case.Footnote 13 Many juvenile courts (e.g., Illinois) view nonviolent juvenile cases as civil rather than criminal, so there is no trial by jury,Footnote 14 and the majority of civil cases do not have trials by jury.Footnote 15

1.2 Statutes and Judicial Precedent

At the federal level, the U.S. Congress creates and enacts a statute (law), and the courts are left to interpret the law.Footnote 16 There is often vagueness or insufficient details from Congress as to how to interpret what they have enacted. If Congress does not agree with how a law is being interpreted by the courts, it has the option to later revise the law to add clarity to any ambiguity. Over time, as courts interpret laws that have been passed, future court decisions are based on those prior court decisions by applying a particular rule of law when there is similarity between a current case and a prior ruling – this is the concept of judicial precedent, known as stare decisis.Footnote 17 Stare decisis is considered to be “horizontal” when a court is deferring to its own decisions, while “vertical” stare decisis is a court deferring to the decisions from higher courts. This concept of a strict judicial precedent is the approach that holds current legal decisions to unambiguous aspects of past legal decisions, regardless of whether the current court agrees with the prior decision.Footnote 18 The contemporary approach of what seems to be a “relaxed” interpretation of judicial precedent allows for flexibility in a judge’s decision in that they do consider legal precedent, but they can override precedent if they think that the earlier decision(s) was incorrect.Footnote 19 In 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court illustrated that stare decisis can quickly disappear in a single court decision.Footnote 20

1.3 Constitutional versus Statutory versus Administrative Law

The various sources of U.S. law are relevant to a good understanding of how to interpret and apply the law. Constitutions exist at the federal and the state levels across the U.S. The highest source for U.S. law is the Constitution of the United States, and adherence to constitutional content takes precedence over any other law or regulation. In fact, the structure set forth by the U.S. Constitution is what outlines the authority given separately to the federal government and the individual states.Footnote 21 The U.S. Constitution also outlines the core protection of individual rights, provides the framework for courts to review laws that might conflict with the Constitution, and creates the U.S. division of government that is separated as the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Most legal cases do not directly involve constitutional law and instead involve statutory law, administrative law, and questions regarding the resulting regulations.Footnote 22 The first ten amendments (the Bill of Rights) that were adopted two years after the U.S. Constitution were considered to be a condition attached to the initial approval of the Constitution, which is why those rights are considered to be so connected to the U.S. Constitution rather than a revision or change of direction.Footnote 23

A very influential level of legal authority is the administrative law level, which refers to the regulations from and administration from federal and state agencies, and because administrative agencies can dictate regulations and rules that directly involve business and everyday life, administrative law can impact HCI and technology. Administrative law finds its source in both federal and state agencies and orders, and it is often more directed and narrow in focus.Footnote 24 At the federal level, there is no specification in the U.S. Constitution that creates these federal administrative agencies, however, they can be created by the three branches of the U.S. government (usually by the legislative branch – U.S. Congress).Footnote 25 Administrative law is derived from statutory law (passed by Congress at the federal level or by various state legislative bodies). Congress creates agencies to focus on and specialize in particular aspects of U.S. statutes or areas of government that require expertise, enforcement, review, and service to the public.Footnote 26 Some agencies are primarily focused on social welfare or public service (Social Security Administration, Department of Health and Human Services, etc.), while other agencies are primarily designed for regulatory purposes (Federal Trade Commission, Environmental Protection Agency, etc.).Footnote 27 The U.S. Congress often delegates its authority to specific federal agencies, not only to oversee and implement statutes but also sometimes to further act under a form of “quasi-legislative authority” to create rules or regulations.Footnote 28 One of the many examples of this would be the REAL ID Act as established by Congress following the recommendations of the 9/11 Commission, where the Department of Homeland Security was subsequently expected to create the standards and implement the statute.Footnote 29 So, this is where administrative law would begin. The Department of Homeland Security was created in 2002 as a response to U.S. efforts to prevent future terrorism, following the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001.Footnote 30 The Secretary of Homeland Security would issue proposed rules (administrative law) relating to the implementation of the REAL ID Act, and following a required comment period (where public input is requested), a final rule would be published – essentially becoming administrative law.

If a scenario arises where the interpretation or implementation of a U.S. statute through administrative law presents the possibility for misapplying the intent of the statute, the U.S. Supreme Court sometimes ends up hearing cases related to administrative law. It is not uncommon for an administrative regulation to flow from a U.S. statute that contains ambiguity.Footnote 31 Judicial deference refers to courts permitting a certain level of independence in how an agency applies a statute. The U.S. Supreme Court has used three levels of deference to administrative agencies regarding such scenarios. Chevron deference has been the highest level since the 1980s (established with Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.),Footnote 32 used for an agency’s interpretation of a statute relating to that agency.

However, in June 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Chevron deference, which will have an unpredictable impact on federal agency regulations.Footnote 33 In the written decision another legal concept – stare decisis – was noted as not being relevant to maintaining the Chevron precedent. This change is especially important to laws that relate to technology because of the fast-moving pace of technology and the frequent reliance on an agency’s interpretation of existing law. We acknowledge that this change presents unpredictability in many areas of technology law. This is not a minor shift, in that a plethora of regulations and court cases rely on the Chevron structure. In Justice Kagan’s dissent, she noted that in areas of technical expertise, this will likely create a significant shift, with the courts and legislature now needing to rely on more specific technical expertise in their cases and proposed legislation.

Of all the various components of the legal framework for digital accessibility, the one that relies most heavily on agency interpretation is the legal requirement for web accessibility under Title III (Public accommodations) of the ADA. Unlike Title II of the ADA, or Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, or the Air Carrier Access Act, all of which have regulations that specify in detail the requirements for web accessibility, requirements for Title III (public accommodations) of the ADA rely on an agency interpretation. Among other things, the regulations state: “A public accommodation shall furnish appropriate auxiliary aids and services where necessary to ensure effective communication with individuals with disabilities. This includes an obligation to provide effective communication to companions who are individuals with disabilities.” However, neither the statute nor the regulations specifically mention websites. Since 1996, the Department of Justice (DOJ) has stated that websites of public accommodations are covered under the “effective communications” requirement of Title III of the ADA, which exists in both the statute and the regulations. Courts have generally (but with some exceptions) deferred to the DOJ interpretation, applying the effective communications requirement to cover all forms of communication, including websites. Sources of reference for this interpretation usually include the initial letter from Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Deval Patrick to Sen. Tom Harkin in 1996Footnote 34 and the DOJ Statement of Interest in the New v. Lucky Brand Jeans case in 2014 explaining the application of the “effective communications” requirement to websites.Footnote 35

Auer deference is the next level (established with Auer v. Robbins),Footnote 36 used for an agency’s interpretation of its own regulations.Footnote 37 The lowest level is Skidmore deference (established with Skidmore v. Swift & Co.),Footnote 38 which is used for agency opinions, letters, manuals, and other guidelines related to administrative regulations. The concept of these levels of deference to administrative law does not permit violation of constitutional rights, other clear statutes, or interpretations that are arbitrary and capricious.Footnote 39

The administrative rulemaking process is guided by a law established in 1946, called the Administrative Procedure Act (APA),Footnote 40 which together with separate mandates from Congress, outlines the procedures for rulemaking, including the requirement for posting notices of proposed rules and publishing the final rules in the Federal Register. The APA also addresses standards for the courts to review administrative rules if a person has been incorrectly affected by the actions of an administrative agency. Agency rules can be categorized as being interpretive, which essentially describes how an agency will implement a statute as written by Congress, or legislative, which carries more weight in that an administrative agency will establish their procedures for carrying out a delegated mandate from a statute.Footnote 41

The legislative rules can be further broken down into substantive versus procedural rules. While procedural rules only impact the procedures by which an agency can enforce and implement a mandate, substantive rules are more like actual statutes, in that they can impact the rights of individuals.Footnote 42 The APA outlines three approaches to administrative rulemaking: exempted, formal, and informal. Exempted rulemaking is outlined in the APA and applies to things such as rules regarding the military, foreign affairs, or government grants.Footnote 43 The formal rulemaking process is the most extensive and longest approach to rulemaking. As such, it is only used when a statute from Congress specifies that the formal process applies.Footnote 44 This extensive process follows the APA procedure with a notice to the public (Notice of Proposed Rulemaking or NPRM), a public hearing (mini trial-like hearing), and finally the official rule, based on a decision from an administrative law judge or other official.Footnote 45 The informal rulemaking process applies to any rulemaking where the formal or exempt process does not apply. There is still the requirement for an NPRM, typically published in the Federal Register, but after a public comment period (now also available online through Regulations.gov), the administrative agency can then issue its final rule. Administrative law, even after the final rule, is not absolute.Footnote 46 Any administrative agency actions can face judicial review, and an individual who believes that an agency’s action should be changed or reversed can file a civil case in the matter, and if there is a potential constitutional issue (“question”) in play, it could also be reviewed by a federal court. In order for this to happen, it would have to be proved that a “protected” right has been violated, which is the doctrine of “standing” (validating that federal review is available for the matter).Footnote 47

1.4 Federal versus State Law

The U.S. legal system has a layer of complexity because of there being not only the federal legal system but also separate legal systems for each state. The laws of one state can be slightly or dramatically different from the laws of another state. This can change over time, for example, there is now a dramatic increase in state laws regarding abortion, since the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs.Footnote 48 Regardless of which state becomes the venue for a legal case, federal law will always be involved whenever there is a constitutional question, a question of individual freedom that is protected by the Bill of Rights, a federal statute (federal tax law, for example), or the regulations of a particular federal agency involved (such as the FDA). Any of the above automatically makes the legal question a federal legal question.

Because of the way that the federal government has limited itself under the U.S. Constitution,Footnote 49 states have significant latitude for issues that do not involve federal questions. States are able to create whatever laws they determine are necessary for their citizenry, and they are only limited by the restrictions of the U.S. Constitution and federal law – in other words, if a particular law is not prohibited by the U.S. Constitution or federal statutes, states are able to create their own statutes in areas such as contract law, tort law, family law, and criminal law. Likewise, state agencies are able to create their own regulations based on state laws, as long as there is no conflict with federal law.

1.5 U.S. Court System

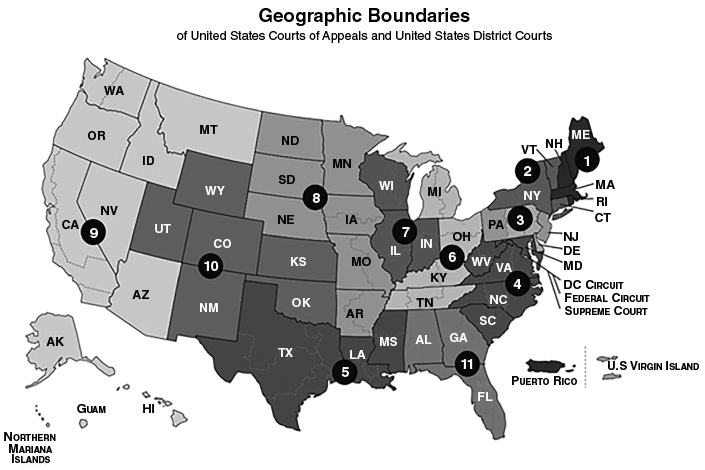

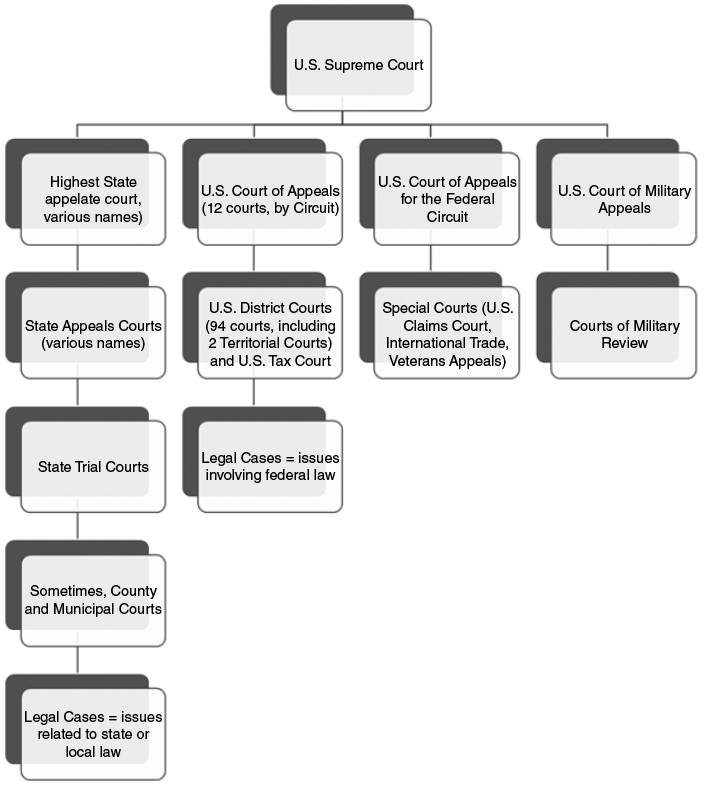

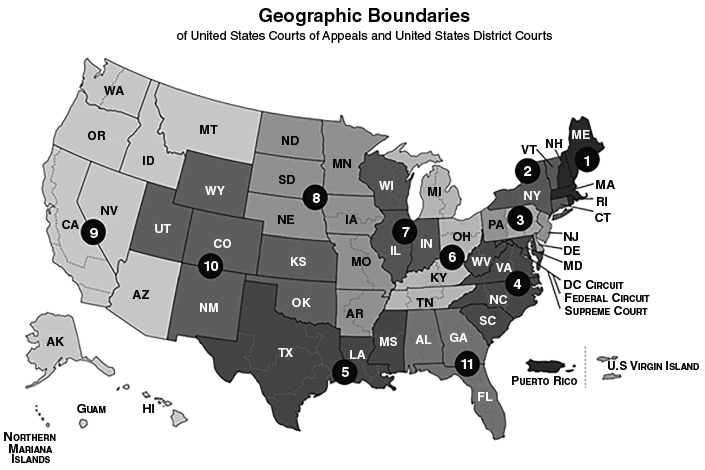

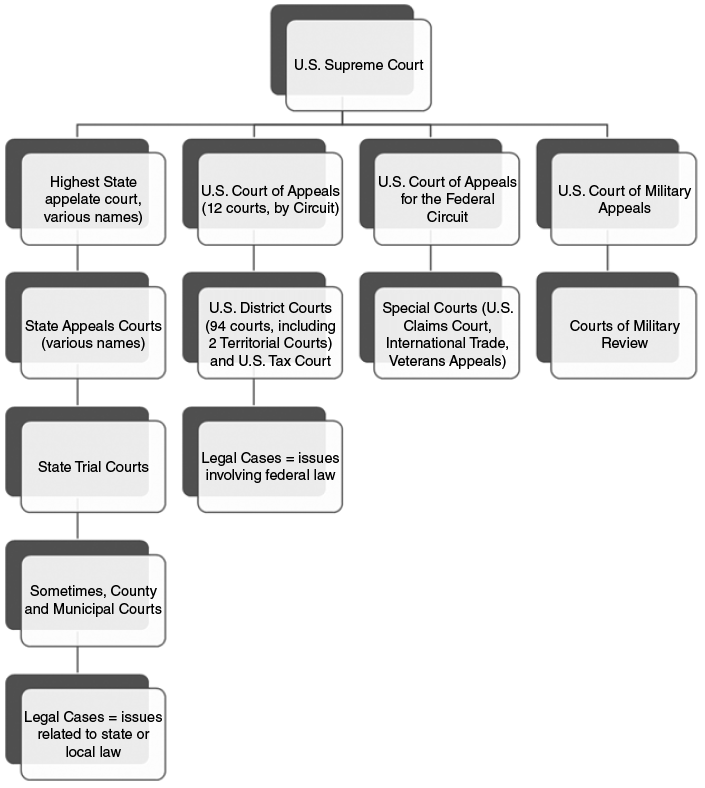

A broad way to consider the court structure in the U.S. is by classifying courts as trial courts (where most cases are initiated) or appellate courts (where cases from trial courts are “appealed” and reviewed for validity). Just as there are federal and state laws, there are federal and state court systems. The origin and structure of the federal court system is traced back to the U.S. Constitution.Footnote 50 The federal court system receives its authority from the U.S. Constitution, which established the U.S. Supreme Court and the Congressional authority to create the lower federal court system. At the federal level in the U.S., the District (trial) courts and Courts of Appeals are organized by thirteen regions (circuits), and each one of those circuits has a Court of Appeals. One of those circuits is considered to be the Federal Circuit, which has federal jurisdiction over international trade, International Property (IP) law (refer to Chapter 6), federal contracts, and similar case topics.Footnote 51 There are 94 district courts spread across those circuits, with at least one district court in every U.S. state, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The distribution of these 94 district courts is determined by state populations. Most federal cases and lawsuits begin at the district court level, where a single judge reaches a decision (ruling) or the suit is settled between the two parties.Footnote 52 The second federal court level is the appellate level (discussed in Section 1.6). The final (and highest) level of the federal court system is the U.S. Supreme Court, which has discretion to choose a limited number of cases from the U.S. Courts of Appeals. It also has the power to consider decisions from state courts whenever there is a question about the U.S. Constitution or federal law.Footnote 53 It is said that 95 percent of all legal activity occurs within state courts.Footnote 54 The state court system structure can vary from one state to another. However, there are general similarities across state court systems within the U.S. they generally have a trial court level (the names of the courts can vary by state), an appellate court level, and a final appellate court (often called the state supreme court). Figure 1.1 provides a general depiction of the U.S. court system.

Figure 1.1 Diagram of the U.S. court system

1.6 The Appellate Process

When a legal issue is appealed, the appellate process is used, and the primary arguments are in the form of written briefs that are submitted to an appellate courtFootnote 55 (at the state level, there can be different names used for the appellate courts – for example, it is called the Court of Appeals in Virginia,Footnote 56 but in Pennsylvania, there are two intermediate appellate courts, one called the Commonwealth Court – for administrative and civil public law – and another called the Superior court – for criminal and private civil law).Footnote 57 Appellate courts only address legal issues, not facts (which need to be remanded to trial courts). At the federal level, there are thirteen Circuit Courts of Appeals across the U.S. Unlike the lower trial court level, where arguments and evidence may be presented, the appellate courts focus on the written briefs and then typically a short time of oral arguments, with a much smaller audience (attorneys and their assistants, rarely clients).Footnote 58 Generally, there is a right to have your case appealed at a mid-level appellate court. However, the top-level federal and state-level appeals courts in the U.S. also have what is known as discretionary jurisdiction, which means that they can decide whether or not to accept an appeal of a lower court’s decision. In fact, very few cases are taken up by the top-level appellate courts. It is important to understand that an appeal is not a second trial of a case with evidence and witnesses. At the mid-level appeals courts, there is often a three-judge panel to review the proceedings of the lower court to evaluate whether or not the decision of the lower court was correct.Footnote 59 After a review of the case, an appellate court will either affirm or reject the decision of the lower court. If an appellate court finds that the law was incorrectly decided by the lower court, it may reject and remand (return) the case to the lower court, which then must follow the guidance of the appellate court’s decision.Footnote 60

1.7 U.S. Circuits and Their Impact on U.S. Law

Because the Circuit Courts of Appeals in the U.S. hear cases based on geographic jurisdiction and not collectively,Footnote 61 there can be different decisions that have been reached in cases in separate Circuits that may share a common legal question. Essentially this means that there could emerge a difference of opinion on a particular legal issue, and when this occurs, this is referred to as a “circuit split.” A circuit split can eventually result in the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately reviewing a particular case.Footnote 62 Another unique aspect of the U.S. federal court system is that there is an impact on precedent (recall the prior mention of stare decisis) and the order in which decisions are binding to lower courts. The result is that a decision by the U.S. Supreme Court is binding to all lower courts. On the other hand, because of the Circuit structure, Court of Appeals and District Courts in one Circuit are not bound by a decision of a Court of Appeals in a different Circuit, even though they are all U.S. federal courts. Lower courts within that particular Circuit would, however, be bound by that decision. So, the practical result is that a particular legal decision could only impact a particular geographic area within the U.S. Figure 1.2 depicts a map of the U.S. Appeals Courts districts, as provided by uscourts.gov.

The concept of jurisdiction involves whether a particular court has the legal authority to hear a particular case.Footnote 63 Courts also cannot hear cases related to events or actions that are in the future (have not yet occurred). For a case to be heard in a federal court, there generally must be a federal statute, treaty, or constitutional question involved. Federal courts have jurisdiction over cases that involve a dispute between two or more states, a case involving U.S. ambassadors or similar public officials, or a dispute between the U.S. federal government and a state. Federal courts also have jurisdiction over cases where the dispute involves an amount greater than $75,000 USD. If the defendant and plaintiff are from different states and the dispute in a case exceeds that threshold, it is considered to be a diversity of citizenship case, where federal jurisdiction can apply.Footnote 64 Once general jurisdiction is determined, the decision between several courts that could have jurisdiction is often based on the geographic nature of the case.Footnote 65 For example, if an incident occurred closer to a District Court in a particular state, that court may be selected to hear the case. “Subject matter jurisdiction” means that a court is legally permitted to hear the case based on the case type (such as a federal contract issue falling under the jurisdiction of a federal court). “Personal jurisdiction” means that a particular court has the legal power over a defendant in the case (such as a state court not being able to force a defendant from another state to appear in court).Footnote 66 At the federal level, the U.S. Supreme Court only receives cases that have already proceeded through the District Court and appellate court levels. The U.S. Supreme Court then has significant latitude over which cases it elects to hear, and it selects from thousands of cases that are submitted each year, typically through a writ of certiorari, which means that the requestor is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the case record from the lower court.Footnote 67 At least four of the nine Supreme Court Justices must agree to review the case for it to reach the docket (agenda) of the Supreme Court.Footnote 68 A refusal to review the case (denial of cert) does not mean that the Supreme Court is validating a decision from the lower court but rather that it will not be reviewed. At the state level, a state’s highest appeals court (often called a state supreme court) is the final stop for most cases, unless there is a federal issue involved.

1.8 Substantive versus Procedural Criminal Law

Criminal law differs from civil law in the U.S., in that its focus is on defining what is considered to be criminal activity and the related penalties for conviction of those activities (such as theft, assault, etc.).Footnote 69 Civil law, by contrast, is focused on the rights of individuals in their dealings with other individuals or organizations.Footnote 70 As a result, most HCI and technology topics tend to be related to civil rather than criminal law, where the focus is on civil liability rather than criminal guilt and conviction. The resulting remedies (based on the court decision) are related to financial damages and/or an injunction (order from a court) that mandates an action or mandates an action to cease.Footnote 71 Most criminal law in the U.S. has its roots in federal- and state-level statutes as well as common law for defining the basics of crimes such as murder and theft. Criminal law carries with it the penalty of fines, imprisonment, or both. And in the U.S., criminal law has evolved to reflect the views of society, by creating or modifying federal and state level statutes.Footnote 72 For the U.S. federal government, criminal statutes are confined by the powers explicitly given in the U.S. Constitution. States in the U.S. can also create their own criminal laws, as long as they do not violate any of the individual rights provided in the U.S. Constitution. Where things get a bit more complicated and controversial is when both the U.S. federal government and individual states make the same activity a crime by statute, both with prescribed repercussions (the term “overcriminalization” is often used). This ultimately results in a “stacking” of violations where someone can be prosecuted for both federal and state crimes for the same offense. A core common law requirement for something to be considered criminal was based on a knowledgeable intent to commit a crime, using the idea of a criminal act (known as actus reus) and a guilty mind (known as mens rea), and under this framework, a simple unknowing mistake was not categorized as a crime.Footnote 73 With the volume of new statutes covering various aspects of what is determined to be criminal activity, there is the ongoing question of whether each new statute is thoroughly vetted for intent and the necessity of the statute.

1.9 Executive Orders in the U.S.

In the U.S., executive orders and memorandums from the President (at the federal level) or from governors (at the state level) are related to the discussion of administrative law. The orders should be based on delegated authority from U.S. federal statutes.Footnote 74 These orders and memos are used to provide specific direction to agencies and government employees regarding either something within the scope of constitutionally provisioned executive power or related to statutes or regulations and how they should be implemented. One example of such an executive order was the 2021 Executive Order on Protecting Americans’ Sensitive Data from Foreign Adversaries, which was released as being supported by 50 U.S.C. 1701 (International Emergency Economic Powers Act), 50 U.S.C. 1601 (National Emergencies Act), and 3 U.S.C. § 301 (relating to the delegation of government functions).Footnote 75 It is important to note that executive orders are prioritized by courts at a lower level than statutes or regulations, and an executive order cannot overrule a statute or regulation or case law, despite what leaders may sometimes claim.

1.10 Sovereign Immunity and U.S. Law

Another concept that the U.S. inherited from English Common Law is the doctrine of “sovereign immunity” for the U.S. federal government and state governments. This was rooted in a tradition of the courts being prevented from suing the king, and it has continued in the U.S. under a structure that requires the U.S. federal government or individual states to permit themselves to be sued for various reasons, yet they have control over what those reasons might be.Footnote 76 For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many states in the U.S. limited their liability for decisions related to the pandemic by relying on this legal tradition of sovereign immunity.

1.11 Understanding Court Opinions and Case and Statutory Citations

When your research into legal frameworks leads to a court opinion, the first step in understanding the implications of that opinion is to determine the date of the decision and whether it was decided by a U.S. federal court or a state court. This is important to determine because the date can help determine whether the decision is valid and holds authority today or whether it has been nullified or modified by a more recent decision. Legal databases are mentioned later in this chapter, and many of those databases will provide a notification regarding decisions that are “overturned” (meaning nullified or amended). Determining the type of court is valuable for understanding whether the decision of that court has authority in a particular situation (whether it’s “good law”) or whether it has been reversed by a higher court. After determining the authority of the court opinion, the next step is to review the facts of the case, which can be found in the first part of the court opinion.Footnote 77 The facts of a case begin with the parties in the dispute, the details of the conflict, and what the parties have requested of the court. This is followed by any procedural facts of the case, particularly if the case was already reviewed by lower courts or administrative agencies.Footnote 78 Finally, there will be the decision that has been reached by the judge or the majority of the judges on the panel for that court (known as the “holding”). This provides insight into how any laws in question should be interpreted or what the next steps for the case will be. If applicable, it will also detail whether there was a new legal rule created or whether an existing legal rule was modified. Sometimes the decision process means it is remanded (sent back) to a lower court or agency. Sometimes the opinion is that the court agrees with (affirms) a decision made by a lower court or agency. There are also instances where a court will reverse a decision from a lower court or administrative agency.Footnote 79

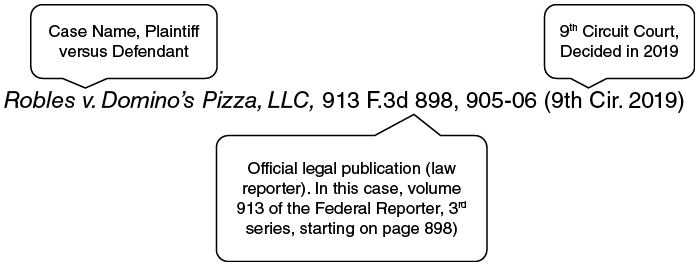

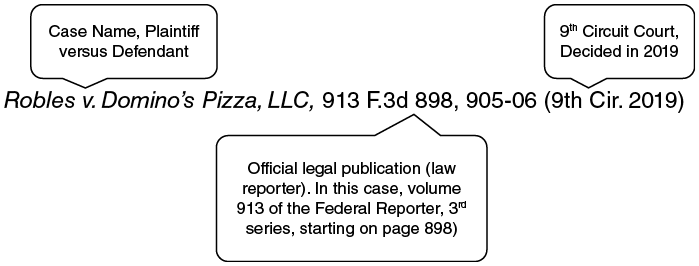

The case citation itself reveals a little bit about the case. The format of case citations can at first seem a bit cryptic. It is very common for anything that can be abbreviated or shortened to be abbreviated. Behind that format is a way to determine the court that decided the case, the date of the decision for the case, the name of the case, and where it can be located. For example, with Nat’l Fed’n of the Blind v. Target Corp., 582 F. Supp. 2d 1185 (N.D. Cal. 2007), the plaintiff (party filing the case) is the National Federation of the Blind, and the defendant named in the case is Target Corporation. The 582 F. Supp. 2d is the reporter volume number and abbreviation (in this case, it is referring to Volume 582 of the Federal Supplement, 2nd series), the 1185 is the first page, and the 2007 is the date the case was decided in the Northern District of California. As another example, a U.S. Supreme Court decision from 1973 might look like this: Chicago Mercantile Exchange v. Deaktor, 410 U.S. 113, 93 S.Ct. 705, 35 L.Ed. 2d 147 (1973). This citation would mean that the plaintiff was Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the defendant was Deaktor, the U.S. Reports volume was 410, with the first page being 113. For this citation, it is also noted that this was published elsewhere (as is usually the case with U.S. Supreme Court cases), including the Supreme Court Reporter and the Lawyer’s Edition. Note that state cases are published in “regional” reporters based on the geographic location of the state. For example, Massachusetts and New York state cases are published in the North Eastern Reporter, which would be abbreviated as N.E. Figure 1.3 shows an illustrated diagram of a federal court case citation (even though states are not always in the geographic reporter that you would expect).

Figure 1.3 Diagram of a federal court citation

When locating and reading a case or ruling (decision) through a database or online legal reference, the decision begins with the heading area, listing the plaintiff(s) and defendant(s), followed by the case number and court where the case was heard. This is followed by information regarding the particular reporters where the case is published and dates specifying when the case was argued and decided (if it has been decided). If this case has already been heard by prior courts, the next section will list the decisions by those prior courts as well as where those decisions can be found (the citations). The next portion of the case is the “disposition,” which describes the final determination (action) by the court. This could be granting or denying a request or (if it is a higher court) it could be affirming or reversing the decision of a lower court or sending the case back (remanding it) to a lower court. Next will be a case summary which provides background information regarding the case, followed by a summary of the court’s opinion and a summary of the facts, history, and holding of the court.

In the court reporters or other databases, there may also be a “syllabus” before the core information from the court, which is another summary of the opinion as added by the court reporter or database. This is supplemental and not part of a court’s decision.

Following this will be the information regarding the counsel (attorneys) who represented the parties in the case. Finally, there will be a lengthier opinion, starting with the judge who wrote the opinion, and this portion is where the finer details are included, such as the history of the case facts, relevant legal issues, relevant statutes, and any relevant past decisions (precedent) that can be applied to the current case. The opinion then details the court’s analysis and their ruling based on that analysis. For U.S. Supreme Court cases (and sometimes appellate court cases), there will be a majority opinion of the Court, followed by any dissenting opinions of the court for the case (judge(s) who disagree with the majority opinion). Note that the order of the above structure might be slightly rearranged or different based on the court (federal versus state) and the level of the court (District Court versus Supreme Court, for example).

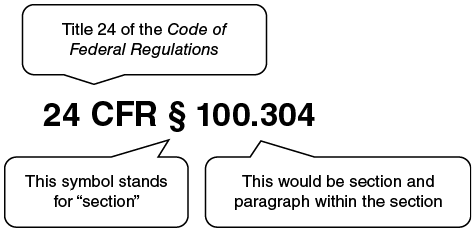

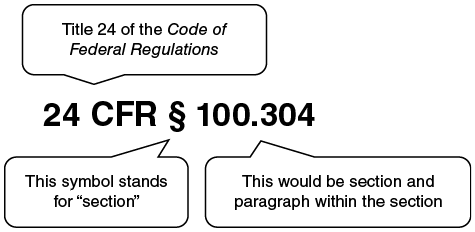

To better understand the parts of a U.S. or state-level Code citation, when examining a citation such as 47 U.S.C. § 618 (2012), the statute is found in Title 47 of the U.S. Code, the symbol represents the word “Section,” which is Section 618, in this case, and the 2012 is the year of that particular U.S. code. Things can be even more specific than just the section, and a subsection and paragraph can even be specified with this citation format. For a federal regulation, it would be listed in the Code of Federal Regulations and might look like 47 C.F.R. § 216.1. For that regulation, it would be referring to Title 47 in the Code of Federal Regulations and section 216.1. Figure 1.4 depicts a diagram of a federal regulation.

Figure 1.4 Diagram of a federal regulation citation

For a state-level example, Cal. Civ. Code § 55.61 would be referring to California state civil code, section 55.61.

1.12 How to Find Legal Sources

There are some key things to consider when doing research that involves legal sources or trying to find legal sources related to an HCI topic. The first approach to legal research should involve determining jurisdiction as introduced earlier. After identifying statutes or regulations that may apply to a technology or situation, it must be determined whether it is a federal statute/regulation or a state statute/regulation, and whether it can be applied to the specific topic at hand. As previously noted regarding the parts of a court case or a statute, it is important to also know the date of the statute or the court decision. It is possible that the decision is no longer applicable because of a more recent decision.

The next step in legal research is locating the sources for the particular topic. If relevant, a good starting point would be federal or state statutes, as those are the primary source for many laws. The second source for research would be cases that are related to those statutes as well as the technology topic itself. A third source for legal research would be administrative regulations or rulings that relate to your topic. Because of the rapidly changing nature of HCI and technology, this may be the most likely place to find regulations related to a more novel technology, as older statutes and rulings may not address it. Often statutes do not keep up with the pace of technology, and as a result, regulations are the best place to search for legal relevance. Finally, law reviews and other scholarly publications can help point the way to other primary and secondary sources for legal research. While a number of printed sources still exist, most recent (and many older) sources are now available in electronic format.

One thing that becomes evident when reading law reviews is that the citation format looks very different from other formats such as APAFootnote 80 and MLA.Footnote 81 Most legal citations follow a format known as “Bluebook” format, which is based on a regularly updated handbook called The Bluebook: A Uniform System of Citation.Footnote 82 Citations from relevant law review articles can often lead to other good sources (both primary and secondary), and popular tools such as Google Scholar can assist you as you uncover legal resources. However, electronic databases such as WestlawFootnote 83 (for secondary sources and copies of primary sources), Lexis/NexisFootnote 84 (for secondary sources and copies of primary sources), or EBSCO Legal CollectionFootnote 85 (for secondary sources) provide a wealth of legal resources. Unless there is existing access to a library which has subscribed to those resources, a subscription fee is involved to access those resources. The CFR, USC, and other state codes are available free of charge. The “eCFR” provides electronic access to the Code of Federal Regulations as offered by the U.S. National Archives.Footnote 86 This tool can be used to easily search by CFR reference or expand/search through various federal regulations. U.S. Code can also be accessed indirectly online through websites such as the Legal Information Institute website managed by Cornell Law School.Footnote 87 Another alternative portal is the Justia.com portal for federal and state codes and statutes.Footnote 88 An example at the state level of a primary source, is the Maryland legal code, which can be found online through the Thurgood Marshall State Law Library.Footnote 89

Another good way to continue legal research is to use a relevant case or statute and find other cases or statutes that might be citing that particular case or statute, helping with the expansion of the legal research. A favorite tool for this is Shepherd’s United States Citations,Footnote 90 which is a feature within LexisNexis that may also be available at select libraries. This resource shows other court decisions that cite the particular case or statute that has already been located (in the legal field, it is referred to as “Shephardizing”). Westlaw provides similar functionality using “flagging” (a red flag on a case means that the case is no longer considered “good law”).

1.13 Applying U.S. Legal Basics to HCI Research

Legal research often follows the “CREAC” (Conclusion, Rule, Explanation, Analysis, Conclusion) approachFootnote 91 and in law review articles, there is a noticeable difference in approach as well as citation procedure and format (using the Bluebook format previously mentioned). There is a focus on identifying the laws that apply and the source of those rulings. There is an examination of the history of the law and its current state – is it still undecided, and as noted before about the federal court system, is there a “circuit split” that impacts the law in the U.S.? The legal jurisdiction for the topic is examined, and the distinction between state and federal law is noted, particularly where there may be a conflict between the two. History and historical precedents (if they are good law) have value in law to a certain degree, and on the other hand, computer developments in 1978 have little relevance today. And, as emphasized before, the concept of stare decisis is critical to determining the legal answer.

When conducting HCI research that involves legal questions or an aspect of technology that might have an impact on law or public policy, it is good to begin with the question of where the research or technology would be used in the U.S. to determine what legal jurisdiction might apply. Once there is a better sense of jurisdiction, the U.S. federal laws and (if relevant) state laws can be examined that might intersect with the research or be impacted by the technology. When exploring potential legal sources, it is good to remember that some sources (e.g., secondary sources such as law reviews) are theoretical versus other sources (court rulings, for example). Court rulings can also be classified as binding precedent (depending on the jurisdiction) versus persuasive precedent (a court opinion that may be considered but is not binding – an opinion on a matter of definition not directly related to the case question, for example). It is also essential to remember that federal law always takes precedence over state law. As discussed previously, on the federal level, a Court of Appeals can overrule a District Court, and the U.S. Supreme Court can overrule a Court of Appeals. At the state level, a mid-level appeals court can overrule a lower-level trial court, and the state’s highest-level court of appeals can overrule the mid-level courts. Unlike HCI research, there is no wiggle room in determining whether the source of the information (legal rulings for this discussion) is of lower or higher quality. With law, a strict priority of weighting is based on the source: constitutions (which have the highest priority), statutes, regulations, case law (which has higher priority but is lower than a constitution and can counteract each other), and executive orders (which have lower priority). Refer to Chapter 11 for information on treaties and laws of other countries.

As noted in Section 1.12, it is then essential to identify additional primary and secondary sources of law that relate to the topic. Are there any statutes or court decisions that directly apply to the research or technology? If there are no clear laws or relevant decisions, the next step would be to determine where there might be similarity from other statutes or case law. Because of the novel and evolving nature of HCI and technology, it is likely that this scenario might occur. Laws may easily predate current and emerging technology, and therefore a framework or relevance for the legal question might be developed based on a similar situation, which may not even be technology related. Recent law review articles might be helpful, as there may be similar topics that are being explored from a legal perspective. However, these case materials and other scholarly resources are theories or research but are not the law. Also note that legal theory tends to be a discussion of legal approaches or novel legal arguments, unlike the type of theories encountered in HCI with hypotheses and rigorous methodologies. Court rulings provide the framework for the legal rules, not quantitative research like might be expected with HCI.