1. Introduction

Since at least the work of Becker, the study of crime and punishment as a problem of economics and choice has received significant attention [Reference Chalfin and McCrary3–Reference Polinsky and Shavell20]. Framed simply, one can conceptualise individuals as rational agents choosing whether or not to commit crimes based on the estimated utility of the two competing choices, while the justice system, by setting standards of proof for conviction and the severity of punishments imposed, attempts to influence this choice in some desired way. Questions then arise as to what the thresholds of evidence or levels of punishments should be that will best optimise some stated objective function; for example, to minimise expected crime rates.

Becker asked how many resources and how much punishment should be used to enforce different kinds of legislation. There, the optimal decisions minimise social loss in income from offences – the sum of damages, costs of apprehension, costs of conviction, and costs of carrying out punishments. This choice of optimal criteria and how it is calculated has led to more discussions. For example, in Becker, the damage to society is the cost of the offence minus the gain to the offender. In other words, the gain for the offender is counted as a gain for society – leading to the conclusion that society should allow efficient crimes. In response, Stigler posits that an offender’s illicit gains should not be counted as society’s gains, suggesting a change to what the legislators should optimise. This view is not without its problems, since society’s decision on what counts as illicit gains changes throughout time [Reference Raskolnikov22]. Others have circumvented the issue by focusing on other optimal conditions or narrowing down the details of the illicit activity being considered. For example, Raskolnikov focused on crime where the illicit gains always equal the harm done. Curry and Doyle introduced a voluntary market option for individuals to achieve the same objective as they would with criminal behaviour. With that, Curry and Doyle showed that minimising the cost of crime corresponds with maximising social welfare. The possibilities to be considered are numerous; Polinsky and Shavell give an excellent overview and discussion on deterrence modelling considerations.

At the same time, a large body of work shows that the justice system often has differential effects on various subgroups of the overall population [Reference Knox, Lowe and Mummolo13–Reference Petersilia17]. Motivated by this, some recent works on the economics of crime have begun to build various metrics of ‘fairness’ into the objective function. A fundamental difficulty with this task is that consensus on a formal definition of fairness is lacking. Further, it is known [Reference Chouldechova4, Reference Kleinberg, Mullainathan and Raghavan11] that some fairness metrics are inherently incompatible with others, such that both cannot possibly be achieved simultaneously. And, since these metrics often test the ‘outcome’ of an algorithm, the issue of fairness is further complicated by the infra-marginality problem, where an outcome test for two groups with different risk distributions can suggest bias in favour of one group even if none exists, or sometimes even if the true bias is in favour of the other group [Reference Simoiu, Corbett-Davies and Goel25]. Which definition of fairness is most desirable transcends mathematics and requires moral arguments and philosophical discussions [Reference Loi and Heitz14, Reference Hu7].

Despite these caveats about fairness, generally, researchers on the economics of crime simply choose a plausible notion of fairness and proceed from there, cognisant that their choice may not be shared by all. For example, Persico proposed a model that imposes a fairness restriction for the police such that police behaviour is defined as fair when they police two subgroups with the same intensity; this is coupled with the goal of maximising the number of successful inspections. Persico concludes that, under certain conditions, forcing the police to behave more fairly reduces the overall crime rate. As an alternative notion, Jung et al. consider fairness as an equality in conditional false positive rates between groups, and also show that the crime rate is minimised when this constraint is upheld. Our work adopts this same notion of fairness and shares many other traits with Jung et al. However, due to some key differences between our model and that of Jung et al., we find that equalising false positive rates between groups generally does not minimise crime, nor optimise a general objective function, if it is indeed even possible in the first place. However, we show that under certain circumstances and objective function choices, the fair scenario is in fact the global optimiser.

This work aims to accomplish the following. First, to introduce a model of crime and deterrence that, while certainly only a vastly simplified version of reality, includes certain notions not otherwise included in prior models of this type. This is done in Section 2, in which we will discuss Jung et al.’s baseline model and introduce our own, highlighting the key differences. Second, based on our model, we aim to explore how the crime rate of society depends on the various choices of the justice system and to determine how the justice system might ‘optimally’ achieve a goal of lowering crime while still keeping in mind the negative impact that punishment can have on innocent individuals. This is done in Section 3, where we will explore how the crime rate of a single group reacts with respect to the threshold

![]() $\tau$

set by the judge and the punishment level

$\tau$

set by the judge and the punishment level

![]() $\kappa$

set by the legislator, and in which we introduce a single group objective function and find optimal values of

$\kappa$

set by the legislator, and in which we introduce a single group objective function and find optimal values of

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

under a variety of circumstances. Finally, to determine based on the model whether or not a specific notion of fairness between groups can be accomplished, and what optimality for the justice system might look like when this fairness consideration for two groups is included in the objective function. This is studied in Section 4, where we extend our analysis to the case of two groups and explore how a notion of fairness impacts the objective function previously introduced in Section 3.

$\kappa$

under a variety of circumstances. Finally, to determine based on the model whether or not a specific notion of fairness between groups can be accomplished, and what optimality for the justice system might look like when this fairness consideration for two groups is included in the objective function. This is studied in Section 4, where we extend our analysis to the case of two groups and explore how a notion of fairness impacts the objective function previously introduced in Section 3.

2. Setup and baseline model overview

Footnote

1

We start with a version of Jung et al.’s model. Individuals in a societal group

![]() $k$

make a binary decision to commit a crime (

$k$

make a binary decision to commit a crime (

![]() $c$

) or to remain innocent (

$c$

) or to remain innocent (

![]() $i$

). An individual who chooses to commit a crime receives reward

$i$

). An individual who chooses to commit a crime receives reward

![]() $\rho$

, while an individual who chooses not to commit a crime receives reward

$\rho$

, while an individual who chooses not to commit a crime receives reward

![]() $\nu$

. The difference between these two quantities is

$\nu$

. The difference between these two quantities is

![]() $\gamma \equiv \rho - \nu$

, and varies from person to person within the group since opportunities both within and outside of crime might naturally vary; let the density

$\gamma \equiv \rho - \nu$

, and varies from person to person within the group since opportunities both within and outside of crime might naturally vary; let the density

![]() $\Gamma _k(\gamma )$

represent the distribution of this quantity within the group. Clearly, those individuals with

$\Gamma _k(\gamma )$

represent the distribution of this quantity within the group. Clearly, those individuals with

![]() $\gamma \leq 0$

have no quantitative incentive to commit crime, while those with

$\gamma \leq 0$

have no quantitative incentive to commit crime, while those with

![]() $\gamma \gt 0$

do. We will assume throughout that the density

$\gamma \gt 0$

do. We will assume throughout that the density

![]() $\Gamma _k \geq 0$

is strictly positive at all positive

$\Gamma _k \geq 0$

is strictly positive at all positive

![]() $\gamma$

values, indicating that it contains some mass in the positive

$\gamma$

values, indicating that it contains some mass in the positive

![]() $\gamma$

region so that there are at least some individuals who are motivated to commit crime.Footnote

2

$\gamma$

region so that there are at least some individuals who are motivated to commit crime.Footnote

2

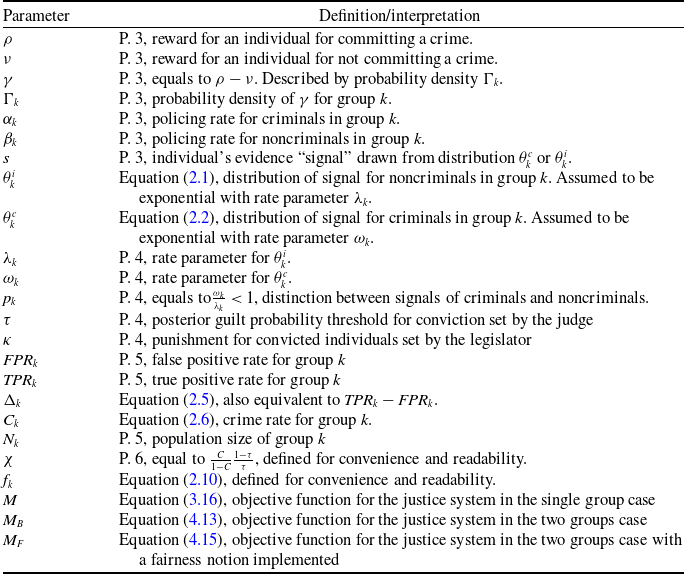

Table 1. List of important model parameters and notations with their definition and/or interpretation in plain language ordered by appearance

Each individual within the group may come under suspicion or scrutiny as a possible criminal and be ‘investigated’ or ‘policed’. Let the group-dependent policing rate for those who choose to commit a crime and those who do not be denoted as

![]() $\alpha _k$

and

$\alpha _k$

and

![]() $\beta _k$

, respectively. We will generally assume that

$\beta _k$

, respectively. We will generally assume that

![]() $\alpha _k\geq \beta _k$

, throughout, in the hope that criminals are at least as likely to be investigated as those who are innocent. Each individual who comes under such scrutiny will produce a random ‘signal’

$\alpha _k\geq \beta _k$

, throughout, in the hope that criminals are at least as likely to be investigated as those who are innocent. Each individual who comes under such scrutiny will produce a random ‘signal’

![]() $s\geq 0$

that represents effectively the amount of evidence that appears to indicate guilt for that individual. The distribution of signals for criminals and innocents within group

$s\geq 0$

that represents effectively the amount of evidence that appears to indicate guilt for that individual. The distribution of signals for criminals and innocents within group

![]() $k$

is denoted as

$k$

is denoted as

![]() $\theta _k^c(s)$

and

$\theta _k^c(s)$

and

![]() $\theta _k^i(s)$

, respectively. We assume, as in Jung et al., that these signals exhibit a Monotone Likelihood Ratio Property (MLRP), meaning that

$\theta _k^i(s)$

, respectively. We assume, as in Jung et al., that these signals exhibit a Monotone Likelihood Ratio Property (MLRP), meaning that

![]() $\frac {\theta _k^c(s)}{\theta _k^i(s)}$

is nondecreasing in

$\frac {\theta _k^c(s)}{\theta _k^i(s)}$

is nondecreasing in

![]() $s.$

That is, a higher signal

$s.$

That is, a higher signal

![]() $s$

never denotes a lower likelihood of being guilty vs innocent. For concreteness, throughout the rest of this work, we will assume that the signals

$s$

never denotes a lower likelihood of being guilty vs innocent. For concreteness, throughout the rest of this work, we will assume that the signals

![]() $s$

are drawn from exponential distributions

$s$

are drawn from exponential distributions

and we define

to guarantee the MLRP. One can interpret the parameter

![]() $p_k$

as essentially indicating how ‘easy’ it is to determine those who are guilty vs innocent within the group

$p_k$

as essentially indicating how ‘easy’ it is to determine those who are guilty vs innocent within the group

![]() $k$

, with

$k$

, with

![]() $p_k$

close to zero indicating that this determination is relatively easy, and

$p_k$

close to zero indicating that this determination is relatively easy, and

![]() $p_k$

near one indicating that the determination is relatively hard.

$p_k$

near one indicating that the determination is relatively hard.

Finally, a judge determines whether the evidence indicates guilt, denoted by

![]() $z=1$

, or innocence, denoted by

$z=1$

, or innocence, denoted by

![]() $z=0$

, for each individual under scrutiny. In contrast to Jung et al., we focus entirely on the case in which the judge determines guilt versus innocence based on the posterior probability of the individual being a criminal, rather than making the decision based directly on the signal. That is, an individual is classified as guilty if the judge determines that their posterior probability of being a criminal given their signal, their group, and a prior belief on guilt is larger than some threshold

$z=0$

, for each individual under scrutiny. In contrast to Jung et al., we focus entirely on the case in which the judge determines guilt versus innocence based on the posterior probability of the individual being a criminal, rather than making the decision based directly on the signal. That is, an individual is classified as guilty if the judge determines that their posterior probability of being a criminal given their signal, their group, and a prior belief on guilt is larger than some threshold

![]() $0\lt \tau \lt 1$

, i.e.

$0\lt \tau \lt 1$

, i.e.

![]() $P(c|s,k) \gt \tau$

; otherwise they are found innocent. The details of this assessment will be provided later. Jung et al. instead focus on policies that are based directly on the signal itself, and which are also based on simple thresholding. There is a discussion within Jung et al. of the possibility of posterior thresholding, in which the authors point out that there is rough equivalency between these two methods – a threshold on signal can be translated to a threshold on posterior and vice versa – as we will elaborate on below. However, for the policy problem that is presented in Jung et al., minimising total crime across groups, it is generally true that the optimal policy will correspond to posterior thresholds that are different for different groups. Here is where our approach fundamentally differs: we will insist in this work that only one posterior threshold exists,

$P(c|s,k) \gt \tau$

; otherwise they are found innocent. The details of this assessment will be provided later. Jung et al. instead focus on policies that are based directly on the signal itself, and which are also based on simple thresholding. There is a discussion within Jung et al. of the possibility of posterior thresholding, in which the authors point out that there is rough equivalency between these two methods – a threshold on signal can be translated to a threshold on posterior and vice versa – as we will elaborate on below. However, for the policy problem that is presented in Jung et al., minimising total crime across groups, it is generally true that the optimal policy will correspond to posterior thresholds that are different for different groups. Here is where our approach fundamentally differs: we will insist in this work that only one posterior threshold exists,

![]() $\tau$

, and then frame our policy problem under this constraint. We make this choice because one focus of this work is on exploring fairness within the context of this problem, and having separate posterior thresholds for each societal group may violate general ethical and/or legal standards held in many societies; this, despite evidence that in reality these standards are sometimes violated [Reference Knox, Lowe and Mummolo13–Reference Fryer6].

$\tau$

, and then frame our policy problem under this constraint. We make this choice because one focus of this work is on exploring fairness within the context of this problem, and having separate posterior thresholds for each societal group may violate general ethical and/or legal standards held in many societies; this, despite evidence that in reality these standards are sometimes violated [Reference Knox, Lowe and Mummolo13–Reference Fryer6].

As a final aspect of the model, anyone found guilty receives punishment

![]() $\kappa$

, set by the legislator, regardless of group. As with the common posterior threshold mentioned above, this assumption comports with general ethical and/or legal standards held in many societies, despite evidence that in reality these standards are sometimes violated [Reference Knox, Lowe and Mummolo13–Reference Fryer6]. In practice, legislators often set a range of punishment levels that judges can choose from to assign to individuals found guilty. But, we will later show that in our framework, the legislator is able to find a single optimal punishment level according to a specific objective function. So, throughout this work, we will assume that the legislator only picks one single punishment level

$\kappa$

, set by the legislator, regardless of group. As with the common posterior threshold mentioned above, this assumption comports with general ethical and/or legal standards held in many societies, despite evidence that in reality these standards are sometimes violated [Reference Knox, Lowe and Mummolo13–Reference Fryer6]. In practice, legislators often set a range of punishment levels that judges can choose from to assign to individuals found guilty. But, we will later show that in our framework, the legislator is able to find a single optimal punishment level according to a specific objective function. So, throughout this work, we will assume that the legislator only picks one single punishment level

![]() $\kappa$

for the entire society, which could be the optimal one. This assumption could be relaxed to form a model closer to reality, but with more complications, including a more complex calculation on the part of the society members that would include a probability distribution of

$\kappa$

for the entire society, which could be the optimal one. This assumption could be relaxed to form a model closer to reality, but with more complications, including a more complex calculation on the part of the society members that would include a probability distribution of

![]() $\kappa$

values that they might receive; this may be considered in future work.

$\kappa$

values that they might receive; this may be considered in future work.

Given the above, an individual then chooses to commit a crime if their expected net utility from committing a crime is higher than not committing crime. The inequality governing an individual’s decision to commit a crime then becomes

Rearranged, we have

where

is a measure of the difference in probability of being found guilty for criminals and innocents within group

![]() $k$

, and is therefore the difference between the true positive rate

$k$

, and is therefore the difference between the true positive rate

![]() $TPR_k$

and false positive rate

$TPR_k$

and false positive rate

![]() $FPR_k$

for group

$FPR_k$

for group

![]() $k$

. Then the overall crime rate, measured as the fraction of people choosing to commit crime for group

$k$

. Then the overall crime rate, measured as the fraction of people choosing to commit crime for group

![]() $k$

satisfies

$k$

satisfies

We assume that the judge has knowledge of the relevant parameters and distributions for all groups, and can then use this knowledge to aid in determining guilt versus innocence for an individual producing a given signal

![]() $s$

. Specifically, the judge makes a Bayesian posterior calculation on the probability of an individual being a criminal based on their signal, group membership, and the known society-wide crime rate

$s$

. Specifically, the judge makes a Bayesian posterior calculation on the probability of an individual being a criminal based on their signal, group membership, and the known society-wide crime rate

![]() $C$

, then decides guilt vs innocence based on the threshold value

$C$

, then decides guilt vs innocence based on the threshold value

![]() $\tau$

on this posterior probability. Let the society-wide crime rate be computed as

$\tau$

on this posterior probability. Let the society-wide crime rate be computed as

where

![]() $\mathcal{G}$

is the number of distinct societal groups (however these might be defined) and

$\mathcal{G}$

is the number of distinct societal groups (however these might be defined) and

![]() $N_k$

and

$N_k$

and

![]() $C_k$

are the fraction of the total society that belongs to group

$C_k$

are the fraction of the total society that belongs to group

![]() $k$

and the crime rate of group

$k$

and the crime rate of group

![]() $k$

, respectively. The posterior probability of an individual being a criminal after observing some signal

$k$

, respectively. The posterior probability of an individual being a criminal after observing some signal

![]() $s$

given a group

$s$

given a group

![]() $k$

is

$k$

is

We note that, from the point of view of an accurate posterior probability, equation (2.7) should use

![]() $C_k$

rather than

$C_k$

rather than

![]() $C$

. However, doing so would essentially represent a prejudice on the part of the judge toward convicting certain groups more readily than others. Since one focus of our work is enforcing fairness within the model, and such a prejudice could readily be construed as unfair, we opt to consider the less biased calculation that uses

$C$

. However, doing so would essentially represent a prejudice on the part of the judge toward convicting certain groups more readily than others. Since one focus of our work is enforcing fairness within the model, and such a prejudice could readily be construed as unfair, we opt to consider the less biased calculation that uses

![]() $C$

rather than

$C$

rather than

![]() $C_k$

.

$C_k$

.

Recall that an individual is classified as guilty (

![]() $z=1)$

if their posterior probability of being a criminal is greater than the threshold set by the judge,

$z=1)$

if their posterior probability of being a criminal is greater than the threshold set by the judge,

![]() $P(c|s,k) \gt \tau$

, with

$P(c|s,k) \gt \tau$

, with

![]() $0\lt \tau \lt 1$

. Then, a crime rate of zero would lead to no one ever being found guilty via (2.7). However, in this circumstance, those individuals with

$0\lt \tau \lt 1$

. Then, a crime rate of zero would lead to no one ever being found guilty via (2.7). However, in this circumstance, those individuals with

![]() $\gamma \gt 0$

will certainly commit crimes, since they will be guaranteed not to be punished, leading to a contradiction. Hence, it must be the case that

$\gamma \gt 0$

will certainly commit crimes, since they will be guaranteed not to be punished, leading to a contradiction. Hence, it must be the case that

![]() $ C_k\gt 0$

, i.e., there will always be some non-zero level of crime if individuals with

$ C_k\gt 0$

, i.e., there will always be some non-zero level of crime if individuals with

![]() $\gamma \gt 0$

exist. Because of this and our assumption about the distributions

$\gamma \gt 0$

exist. Because of this and our assumption about the distributions

![]() $\theta$

, without loss of generality, we can rewrite (2.7) as

$\theta$

, without loss of generality, we can rewrite (2.7) as

Due again to the MLRP for the distributions

![]() $\theta _k^i$

and

$\theta _k^i$

and

![]() $\theta _k^c$

, for any given crime rate

$\theta _k^c$

, for any given crime rate

![]() $ C\lt 1$

the posterior probability of guilt increases with increasing signal, approaching unity as

$ C\lt 1$

the posterior probability of guilt increases with increasing signal, approaching unity as

![]() $s\to \infty$

and having a minimum value at

$s\to \infty$

and having a minimum value at

![]() $s=0$

; for

$s=0$

; for

![]() $ C=1$

the probability is always (correctly) unity for any signal. Then for any

$ C=1$

the probability is always (correctly) unity for any signal. Then for any

![]() $ C\lt 1$

and decision threshold

$ C\lt 1$

and decision threshold

![]() $\tau$

, there will always exist a threshold signal value

$\tau$

, there will always exist a threshold signal value

![]() $s_\tau$

such that only those individuals with

$s_\tau$

such that only those individuals with

![]() $s\geq s_\tau$

are found guilty. If

$s\geq s_\tau$

are found guilty. If

![]() $\tau \leq P(c|0,k)\equiv \tau _0$

this threshold is just

$\tau \leq P(c|0,k)\equiv \tau _0$

this threshold is just

![]() $s_\tau =0$

: everyone is always found guilty in this case. Otherwise, the signal threshold is given by

$s_\tau =0$

: everyone is always found guilty in this case. Otherwise, the signal threshold is given by

where

To reiterate, whenever

then the signal threshold is given by (2.9); otherwise we are in the regime where

![]() $\tau \leq \tau _0$

and everyone is found guilty for all signals, so that

$\tau \leq \tau _0$

and everyone is found guilty for all signals, so that

![]() $s_\tau =0$

and we can effectively set

$s_\tau =0$

and we can effectively set

![]() $f_k=1$

. The existence of a unique

$f_k=1$

. The existence of a unique

![]() $s_\tau$

for each

$s_\tau$

for each

![]() $\tau$

highlights the equivalency between posterior and signal thresholding mentioned above.

$\tau$

highlights the equivalency between posterior and signal thresholding mentioned above.

We can now compute the total probability of being found guilty conditional on investigation for both criminals and innocents of group

![]() $k$

:

$k$

:

Multiplying the quantities in (2.11) and (2.12) by

![]() $\beta$

and

$\beta$

and

![]() $\alpha$

, respectively, gives the false positive rate

$\alpha$

, respectively, gives the false positive rate

![]() $FRP_k$

and true positive rate

$FRP_k$

and true positive rate

![]() $TPR_k$

for group

$TPR_k$

for group

![]() $k$

. Plugging equations (2.11) and (2.12) into equation (2.5), and being careful of inequality (2.10) we have

$k$

. Plugging equations (2.11) and (2.12) into equation (2.5), and being careful of inequality (2.10) we have

\begin{equation} \Delta _k = \begin{cases} \alpha _k f_k^{\frac {p_k}{1-p_k}} - \beta _k f_k^{\frac {1}{1-p_k}}, & f_k \leq 1\\[5pt] \alpha _k - \beta _k, & f_k \gt 1. \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \Delta _k = \begin{cases} \alpha _k f_k^{\frac {p_k}{1-p_k}} - \beta _k f_k^{\frac {1}{1-p_k}}, & f_k \leq 1\\[5pt] \alpha _k - \beta _k, & f_k \gt 1. \end{cases} \end{equation}

We observe that since

![]() $0\lt p_k \lt 1$

,

$0\lt p_k \lt 1$

,

![]() $\frac {p_k}{1-p_k} \lt \frac {1}{1-p_k}.$

So,

$\frac {p_k}{1-p_k} \lt \frac {1}{1-p_k}.$

So,

![]() $f_k^{\frac {p_k}{1-p_k}} \geq f_k^{\frac {1}{1-p_k}}$

when

$f_k^{\frac {p_k}{1-p_k}} \geq f_k^{\frac {1}{1-p_k}}$

when

![]() $f_k\leq 1$

. Combined with our assumption that

$f_k\leq 1$

. Combined with our assumption that

![]() $\alpha _k\geq \beta _k$

we have

$\alpha _k\geq \beta _k$

we have

![]() $TPR_k\geq FPR_k$

and

$TPR_k\geq FPR_k$

and

![]() $\Delta _k\geq 0$

.

$\Delta _k\geq 0$

.

Given all of the group-dependent parameters, as well as

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

, (2.6) is an implicit equation for the crime rate

$\kappa$

, (2.6) is an implicit equation for the crime rate

![]() $C_k$

. In the remainder of this work, we study solutions to this equation in both the single group and two-group cases, and use the crime rates obtained to solve optimisation problems for

$C_k$

. In the remainder of this work, we study solutions to this equation in both the single group and two-group cases, and use the crime rates obtained to solve optimisation problems for

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

.

$\kappa$

.

3. One group

In this section, we will focus on the properties of solutions to equation (2.6) for one single group. For ease of reading, we drop the subscript

![]() $k$

since in this case all parameters and variables belong to a singular group, and in this case,

$k$

since in this case all parameters and variables belong to a singular group, and in this case,

![]() $C$

and

$C$

and

![]() $C_k$

are identical. We define two functions based on the LHS and RHS of equation (2.6):

$C_k$

are identical. We define two functions based on the LHS and RHS of equation (2.6):

In (3.2) we have emphasised that

![]() $\Delta$

is a function of

$\Delta$

is a function of

![]() $C$

. The crime rate solves

$C$

. The crime rate solves

![]() $g = h.$

The function

$g = h.$

The function

![]() $g$

is straightforward, but we will need to explore the function

$g$

is straightforward, but we will need to explore the function

![]() $h$

further. First, we will show that for some parameter region,

$h$

further. First, we will show that for some parameter region,

![]() $h$

has a minimum in the interior of its domain as described in the following lemma.

$h$

has a minimum in the interior of its domain as described in the following lemma.

Lemma 3.1.

![]() $h(C)$

has a minimum at

$h(C)$

has a minimum at

![]() $C_*=\tau$

when

$C_*=\tau$

when

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1.$

The minimum is

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1.$

The minimum is

where

\begin{equation*}\Delta _* = \left (\alpha \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {1}{1-p}} \right )\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}\Delta _* = \left (\alpha \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {1}{1-p}} \right )\end{equation*}

is a constant.

Proof. Recall that

![]() $f$

is a function of

$f$

is a function of

![]() $C$

given in (2.10). Then equation (2.13) is equivalent to

$C$

given in (2.10). Then equation (2.13) is equivalent to

\begin{equation} \Delta = \begin{cases} \alpha f^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta f^{\frac {1}{1-p}}, & C \lt \dfrac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }}\\[15pt] \alpha - \beta , & C \geq \dfrac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }}, \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \Delta = \begin{cases} \alpha f^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta f^{\frac {1}{1-p}}, & C \lt \dfrac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }}\\[15pt] \alpha - \beta , & C \geq \dfrac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }}, \end{cases} \end{equation}

where

![]() $f$

is still a function of

$f$

is still a function of

![]() $C$

. And so, when

$C$

. And so, when

![]() $C \gt \frac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }} \equiv C_0$

,

$C \gt \frac {1}{1+ p\frac {\alpha }{\beta }\frac {1-\tau }{\tau }} \equiv C_0$

,

a constant with respect to

![]() $C$

. Note that

$C$

. Note that

is also a positive constant. The derivative of

![]() $h$

is computed to be

$h$

is computed to be

\begin{align} \frac {\text{d} h}{\text{d} C} &= \begin{cases} -\Gamma (\kappa \Delta ) \kappa \dfrac {\text{d} \Delta }{\text{d} C} =-q(\alpha f^{-1}p - \beta ), & C \lt C_0 \\[8pt] 0, & C \gt C_0. \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\text{d} h}{\text{d} C} &= \begin{cases} -\Gamma (\kappa \Delta ) \kappa \dfrac {\text{d} \Delta }{\text{d} C} =-q(\alpha f^{-1}p - \beta ), & C \lt C_0 \\[8pt] 0, & C \gt C_0. \end{cases} \end{align}

where

Then, any critical point

![]() $C_*$

of

$C_*$

of

![]() $h(C)$

in

$h(C)$

in

![]() $(0,C_0)$

can only occur when

$(0,C_0)$

can only occur when

![]() $\alpha f^{-1}p - \beta = 0.$

Substituting

$\alpha f^{-1}p - \beta = 0.$

Substituting

![]() $f$

from (2.10) and solving, we find the critical point

$f$

from (2.10) and solving, we find the critical point

![]() $C_*=\tau$

, which is also equivalent to

$C_*=\tau$

, which is also equivalent to

![]() $\chi =1$

. However, this critical point will exist iff

$\chi =1$

. However, this critical point will exist iff

![]() $C_* \lt C_0$

; after some algebra this is equivalent to

$C_* \lt C_0$

; after some algebra this is equivalent to

Under this condition, we have that for

![]() $C\lt C_*$

,

$C\lt C_*$

,

![]() $\frac {dh}{dC}\lt 0$

, while for

$\frac {dh}{dC}\lt 0$

, while for

![]() $C_*\lt C\lt C_0$

we have

$C_*\lt C\lt C_0$

we have

![]() $\frac {\text{d}h}{\text{d}C}\gt 0$

, indicating a minimum at

$\frac {\text{d}h}{\text{d}C}\gt 0$

, indicating a minimum at

![]() $C=C_*$

. Further,

$C=C_*$

. Further,

where

\begin{align} \Delta _* = \left (\alpha \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {1}{1-p}} \right ) \end{align}

\begin{align} \Delta _* = \left (\alpha \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {p}{1-p}} - \beta \left (\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\right )^{\frac {1}{1-p}} \right ) \end{align}

is a constant.

The proof above also leads to the following lemma:

Lemma 3.2.

![]() $h(C)$

is monotonically decreasing on

$h(C)$

is monotonically decreasing on

![]() $(0,C_0)$

when

$(0,C_0)$

when

![]() $\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \geq 1.$

$\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \geq 1.$

Next, we will prove a lemma that will help us understand how many times

![]() $g$

and

$g$

and

![]() $h$

intersect which corresponds to the number of solutions to the crime rate equation.

$h$

intersect which corresponds to the number of solutions to the crime rate equation.

Lemma 3.3.

![]() $ \frac {\text{d}h}{\text{d}C} \lt 1$

when

$ \frac {\text{d}h}{\text{d}C} \lt 1$

when

![]() $1 - \frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta }$

for

$1 - \frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta }$

for

![]() $C \in (0,C_0)$

.

$C \in (0,C_0)$

.

Proof. For ease of reading we define

![]() $\phi (C) = \alpha f^{-1} p - \beta =\beta \frac {1-C}{C}\frac {\tau }{1-\tau }-\beta .$

We first compute

$\phi (C) = \alpha f^{-1} p - \beta =\beta \frac {1-C}{C}\frac {\tau }{1-\tau }-\beta .$

We first compute

So, in the domain

![]() $C \in (0,C_0)$

,

$C \in (0,C_0)$

,

Here,

![]() $\phi (C_0) = p \alpha - \beta .$

So, by rearranging our initial assumption and since

$\phi (C_0) = p \alpha - \beta .$

So, by rearranging our initial assumption and since

![]() $f^{-1} \gt 1,$

$f^{-1} \gt 1,$

Rearranging, we have

The lemmas above lead to the following uniqueness theorem.

Theorem 3.4.

If

![]() $1 - \frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta }$

for

$1 - \frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta }$

for

![]() $C \in (0,C_0)$

then there is a unique solution to equation (2.6

).

$C \in (0,C_0)$

then there is a unique solution to equation (2.6

).

Proof. Recall from equation (3.5) that

![]() $0\lt h(0)\leq 1$

. Also,

$0\lt h(0)\leq 1$

. Also,

![]() $h(1) \lt h(0)\leq 1$

from properties of cumulative distribution functions and our assumption that

$h(1) \lt h(0)\leq 1$

from properties of cumulative distribution functions and our assumption that

![]() $\Gamma \gt 0$

. We have

$\Gamma \gt 0$

. We have

![]() $g(0) = 0$

and

$g(0) = 0$

and

![]() $ g(1) = 1$

. If

$ g(1) = 1$

. If

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1,$

then

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1,$

then

![]() $h(c)$

is monotonic by Lemma 3.2. And so there must only be one intersection between

$h(c)$

is monotonic by Lemma 3.2. And so there must only be one intersection between

![]() $g(C)$

and

$g(C)$

and

![]() $h(C).$

If

$h(C).$

If

![]() $1-\frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

for

$1-\frac {1}{q \beta } \leq \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

for

![]() $C \in (0,C_0)$

, then by Lemma 3.3,

$C \in (0,C_0)$

, then by Lemma 3.3,

![]() $\frac {dh}{dC} \lt 1 = \frac {dg}{dC}.$

Similarly, there must be only one intersection between

$\frac {dh}{dC} \lt 1 = \frac {dg}{dC}.$

Similarly, there must be only one intersection between

![]() $g(C)$

and

$g(C)$

and

![]() $h(C).$

$h(C).$

However, if it is the case that

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1-\frac {1}{q\beta }$

for some

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1-\frac {1}{q\beta }$

for some

![]() $C \in (0,C_0)$

, there could be multiple solutions, as illustrated in Figure 1. To summarise the findings of the theorems above and as illustrated in Figure 1, when

$C \in (0,C_0)$

, there could be multiple solutions, as illustrated in Figure 1. To summarise the findings of the theorems above and as illustrated in Figure 1, when

![]() $ \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

there is a unique crime rate for any given

$ \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

there is a unique crime rate for any given

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

, and the crime rate is increasing with

$\kappa$

, and the crime rate is increasing with

![]() $\tau$

for any

$\tau$

for any

![]() $\tau \gt \tau _0$

; that is, crime is minimised when everyone investigated is found guilty. On the other hand, when

$\tau \gt \tau _0$

; that is, crime is minimised when everyone investigated is found guilty. On the other hand, when

![]() $ \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, there are potentially multiple crime rates consistent with (2.6) for certain

$ \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, there are potentially multiple crime rates consistent with (2.6) for certain

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

. However, there is a threshold

$\kappa$

. However, there is a threshold

![]() $\tau _*=C_*=h(C_*)$

that yields the smallest crime rate possible, in which not everyone investigated is found guilty.

$\tau _*=C_*=h(C_*)$

that yields the smallest crime rate possible, in which not everyone investigated is found guilty.

Recall that

![]() $p= \frac {\omega }{\lambda }\lt 1$

is the ratio of the decay rate of the signal for innocents and the decay rate of the signal for criminals, and that

$p= \frac {\omega }{\lambda }\lt 1$

is the ratio of the decay rate of the signal for innocents and the decay rate of the signal for criminals, and that

![]() $p$

closer to 1 indicates that the signal of the criminals and innocents are less distinguishable while lower

$p$

closer to 1 indicates that the signal of the criminals and innocents are less distinguishable while lower

![]() $p$

indicates that the signal of criminals and innocents are more distinguishable. Similarly, the ratio

$p$

indicates that the signal of criminals and innocents are more distinguishable. Similarly, the ratio

![]() $\frac {\beta }{\alpha }$

denotes how different the policing rate is for innocents vs. criminals, with a low ratio meaning that innocents are policed notably less than criminals and a ratio approaching 1 indicating that they are policed at essentially the same rate. Let us rewrite the region

$\frac {\beta }{\alpha }$

denotes how different the policing rate is for innocents vs. criminals, with a low ratio meaning that innocents are policed notably less than criminals and a ratio approaching 1 indicating that they are policed at essentially the same rate. Let us rewrite the region

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

instead as

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

instead as

![]() $p \lt \frac {\beta }{\alpha }.$

Then this region corresponds to one in which the signals between the innocents and the criminals are more distinguishable than their policing rate ratio would suggest. Intuitively, this means that the judge is able to add something valuable to the guilt determination process, and further narrow down who is guilty vs innocent beyond the relatively crude distinction made by the police. Because of this, the judge can choose a threshold

$p \lt \frac {\beta }{\alpha }.$

Then this region corresponds to one in which the signals between the innocents and the criminals are more distinguishable than their policing rate ratio would suggest. Intuitively, this means that the judge is able to add something valuable to the guilt determination process, and further narrow down who is guilty vs innocent beyond the relatively crude distinction made by the police. Because of this, the judge can choose a threshold

![]() $\tau _*$

that minimises crime rate without finding everyone guilty, as shown above. Conversely, the region

$\tau _*$

that minimises crime rate without finding everyone guilty, as shown above. Conversely, the region

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, equivalently

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, equivalently

![]() $p \geq \frac {\beta }{\alpha },$

corresponds to the case where the signals between the innocents and criminals are at most as distinguishable as their policing rate ratio would suggest. In other words, the judge is not as efficient as the police in determining guilt vs innocence, and does not add much of value to the process. Here, the judge minimises crime by just finding everyone guilty, as in this case, the police will have already largely been able to determine guilt before any trial occurs. Generally, it seems plausible that the former case, where the judge is better able to determine guilt vs innocence than the police, is the more realistic of the two.

$p \geq \frac {\beta }{\alpha },$

corresponds to the case where the signals between the innocents and criminals are at most as distinguishable as their policing rate ratio would suggest. In other words, the judge is not as efficient as the police in determining guilt vs innocence, and does not add much of value to the process. Here, the judge minimises crime by just finding everyone guilty, as in this case, the police will have already largely been able to determine guilt before any trial occurs. Generally, it seems plausible that the former case, where the judge is better able to determine guilt vs innocence than the police, is the more realistic of the two.

In the next two subsections, we will discuss the case where there could be multiple solutions. Then, we will explore how the crime rate changes in relation to the threshold

![]() $\tau$

and the punishment level

$\tau$

and the punishment level

![]() $\kappa$

and consider a reasonable objective function for the judge and the legislator to minimise.

$\kappa$

and consider a reasonable objective function for the judge and the legislator to minimise.

Figure 1. Intersection(s) of

![]() $g(C)$

and

$g(C)$

and

![]() $h(C)$

. The dashed lines from top to bottom correspond to the regions

$h(C)$

. The dashed lines from top to bottom correspond to the regions

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

,

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

,

![]() $1 -\frac {1}{qb} \lt \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, and

$1 -\frac {1}{qb} \lt \frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, and

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1 -\frac {1}{qb}$

, respectively. The solid horizontal line indicates the region in which

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1 -\frac {1}{qb}$

, respectively. The solid horizontal line indicates the region in which

![]() $f=1$

. Panel (a) is constructed at a lower threshold

$f=1$

. Panel (a) is constructed at a lower threshold

![]() $\tau$

than that used in (b).

$\tau$

than that used in (b).

3.1. Remark on multiple crime rates

As described above, equation (2.6) may be consistent for several different crime rates

![]() $C$

, that is, the solution might not be unique in some parameter regions. In that case, it is not immediately clear which of these consistent crime rates would manifest, as the overall model assumes that criminals can determine their expected utilities perfectly, and those depend on the crime rate observed. However, we will show that, by our assumption that individuals want to maximise their utility, the smallest of these consistent crime rates will be the one to occur.

$C$

, that is, the solution might not be unique in some parameter regions. In that case, it is not immediately clear which of these consistent crime rates would manifest, as the overall model assumes that criminals can determine their expected utilities perfectly, and those depend on the crime rate observed. However, we will show that, by our assumption that individuals want to maximise their utility, the smallest of these consistent crime rates will be the one to occur.

Suppose there are multiple solutions to (2.6), labelled

![]() $C^{(1)}\lt C^{(2)}\lt \cdots \lt C^{(n)}$

. Each such crime rate can be thought of as representing a Nash Equilibrium of the system. That is, any solution

$C^{(1)}\lt C^{(2)}\lt \cdots \lt C^{(n)}$

. Each such crime rate can be thought of as representing a Nash Equilibrium of the system. That is, any solution

![]() $C^{(i)}$

corresponds to a value

$C^{(i)}$

corresponds to a value

![]() $\gamma ^{(i)}$

that has two properties:

$\gamma ^{(i)}$

that has two properties:

![]() $C^{(i)}=\int _{\gamma ^{(i)}}^\infty \Gamma (\gamma ) \text{d}\gamma$

(the solution is consistent); and if individuals with

$C^{(i)}=\int _{\gamma ^{(i)}}^\infty \Gamma (\gamma ) \text{d}\gamma$

(the solution is consistent); and if individuals with

![]() $\gamma \gt \gamma ^{(i)}$

commit crimes and those with

$\gamma \gt \gamma ^{(i)}$

commit crimes and those with

![]() $\gamma \lt \gamma ^{(i)}$

do not, no individual is tempted to deviate from this unilaterally (a Nash Equilibrium). Note that these threshold

$\gamma \lt \gamma ^{(i)}$

do not, no individual is tempted to deviate from this unilaterally (a Nash Equilibrium). Note that these threshold

![]() $\gamma$

values lie in the order

$\gamma$

values lie in the order

![]() $\gamma ^{(n)}\lt \gamma ^{(n-1)}$

$\gamma ^{(n)}\lt \gamma ^{(n-1)}$

![]() $\lt \cdots \lt \gamma ^{(1)}$

.

$\lt \cdots \lt \gamma ^{(1)}$

.

However, the expected utilities for individuals among these Nash Equilibria are not equal. Note that those with

![]() $\gamma \gt \gamma ^{(1)}$

will commit crimes no matter which equilibrium is selected, and those with

$\gamma \gt \gamma ^{(1)}$

will commit crimes no matter which equilibrium is selected, and those with

![]() $\gamma \lt \gamma ^{(n)}$

will not commit crimes no matter which is selected, so that we need only consider those individuals with

$\gamma \lt \gamma ^{(n)}$

will not commit crimes no matter which is selected, so that we need only consider those individuals with

![]() $\gamma ^{(n)}\lt \gamma \lt \gamma ^{(1)}$

and determine which equilibrium they might prefer. For a fixed behaviour – commit crimes vs not – utility is decreasing with increasing probability of punishment, which itself increases with crime rate. Hence, for any given individual under consideration we need only contrast two of the equilibria:

$\gamma ^{(n)}\lt \gamma \lt \gamma ^{(1)}$

and determine which equilibrium they might prefer. For a fixed behaviour – commit crimes vs not – utility is decreasing with increasing probability of punishment, which itself increases with crime rate. Hence, for any given individual under consideration we need only contrast two of the equilibria:

![]() $C^{(1)}$

, in which case they do not commit crime and crime is as low as possible; and

$C^{(1)}$

, in which case they do not commit crime and crime is as low as possible; and

![]() $C^{(j)}$

, which is the lowest crime rate for which the corresponding

$C^{(j)}$

, which is the lowest crime rate for which the corresponding

![]() $\gamma ^{(j)}$

is less than the

$\gamma ^{(j)}$

is less than the

![]() $\gamma$

value of the individual in question, which is the lowest crime state in which that person commits crime. Then this individual will prefer the equilibrium at

$\gamma$

value of the individual in question, which is the lowest crime state in which that person commits crime. Then this individual will prefer the equilibrium at

![]() $C^{(1)}$

so long as

$C^{(1)}$

so long as

Upon rearranging terms and writing existing quantities in terms of

![]() $\gamma _1$

, the above inequality is equivalent to

$\gamma _1$

, the above inequality is equivalent to

Noting that the term in brackets is positive, this inequality holds for all individuals in question, meaning that they all prefer the lowest crime equilibrium above all others. Therefore, even in cases where there are multiple solutions to (2.6), one would expect that the lowest crime solution should be the one obtained.

3.2. Judge’s and legislator’s objective

We now model the choice of

![]() $\tau$

and

$\tau$

and

![]() $\kappa$

as optimisation problems for the judge and legislator. As a very simple first possibility, perhaps the judge and legislator are working in unison to simply minimise the crime rate

$\kappa$

as optimisation problems for the judge and legislator. As a very simple first possibility, perhaps the judge and legislator are working in unison to simply minimise the crime rate

![]() $C$

. Given the results above, for a fixed punishment level

$C$

. Given the results above, for a fixed punishment level

![]() $\kappa$

, crime is minimised in one of two ways. First, if

$\kappa$

, crime is minimised in one of two ways. First, if

![]() $\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then crime is minimised at rate

$\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then crime is minimised at rate

![]() $C_0=h(C_0)$

from (3.4), since

$C_0=h(C_0)$

from (3.4), since

![]() $h(C)$

is monotonically decreasing on

$h(C)$

is monotonically decreasing on

![]() $(0,C_0)$

in this case. This corresponds to selecting any threshold

$(0,C_0)$

in this case. This corresponds to selecting any threshold

![]() $\tau \in (0,\tau _0]$

, in which case all individuals are found guilty, and

$\tau \in (0,\tau _0]$

, in which case all individuals are found guilty, and

![]() $\tau _0=1/\left [1+\frac {\beta }{p\alpha }\frac {1-C_0}{C_0}\right ].$

If

$\tau _0=1/\left [1+\frac {\beta }{p\alpha }\frac {1-C_0}{C_0}\right ].$

If

![]() $\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, then crime is minimised at rate

$\frac {p\alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

, then crime is minimised at rate

![]() $C_*=h(C_*)$

from (3.9), since that is where

$C_*=h(C_*)$

from (3.9), since that is where

![]() $h(C)$

is minimised in this case (and cases of multiple solutions here will still exhibit the smallest crime rate possible). This corresponds to selecting threshold

$h(C)$

is minimised in this case (and cases of multiple solutions here will still exhibit the smallest crime rate possible). This corresponds to selecting threshold

![]() $\tau =\tau _*=C_*$

; in this case, not all individuals are found guilty. In either of these cases, the crime rate simply decreases with

$\tau =\tau _*=C_*$

; in this case, not all individuals are found guilty. In either of these cases, the crime rate simply decreases with

![]() $\kappa$

, indicating that arbitrarily large punishment should be sought, and no global minimum of crime truly exists.

$\kappa$

, indicating that arbitrarily large punishment should be sought, and no global minimum of crime truly exists.

Of course, it is not clear that in reality severe punishment (for a given threshold) always leads to lower crime. This model makes many simplifying assumptions that are perhaps only approximately true, not least of which the idea that the choice to commit crimes is always based on a logical cost–benefit analysis; crimes of passion do exist, after all. This assumption could be relaxed to allow for individuals to commit crimes even if it is not economically beneficial, but we leave that for future work. But beyond this, even if the model were a perfect simulacrum of the criminal justice system, the objective of simply minimising crime does not appear very satisfying. It suggests draconian punishment, ignoring the fact that these punishments are sometimes, unfortunately, meted out to innocent people. Further, it indicates that the posterior threshold for punishment should be very small – either small enough so that all are guilty, or set to match

![]() $C_*$

, which is being made as small as possible – which generally conflicts with Western ideals that posteriors at least be “the preponderance of evidence,” if not higher.

$C_*$

, which is being made as small as possible – which generally conflicts with Western ideals that posteriors at least be “the preponderance of evidence,” if not higher.

We therefore propose an alternative objective function. Certainly, low crime is still desired, as that minimises the impact of crime on victims, among many other things. However, this desire should be balanced against harm that could also be done to innocent individuals through erroneous punishment. The portion of the objective indicating harm could take many forms and include many items, such as opportunity costs incurred by punishing innocent individuals, or fear and distrust that very severe punishments might instil in citizens. However, to avoid introducing too many other considerations to the model, we stick with a relatively basic term that can be included without much difficulty, and which essentially directly measures the amount of punishment applied to innocent people. We therefore propose that the judge and legislator might consider the objective function

Here,

![]() $\lambda \gt 0$

and

$\lambda \gt 0$

and

![]() $n\gt 0$

are both parameters that change the balance between desiring low crime vs low punishment for innocent individuals who are found guilty. We note that for

$n\gt 0$

are both parameters that change the balance between desiring low crime vs low punishment for innocent individuals who are found guilty. We note that for

![]() $n=1$

, a seemingly natural choice, the second term is directly proportional to the total amount of punishment meted out to innocents, with a constant of proportionality

$n=1$

, a seemingly natural choice, the second term is directly proportional to the total amount of punishment meted out to innocents, with a constant of proportionality

![]() $\lambda$

. However, as we will show below, choosing

$\lambda$

. However, as we will show below, choosing

![]() $n=1$

leads to an unsatisfying solution to the optimisation problem.

$n=1$

leads to an unsatisfying solution to the optimisation problem.

While the natural choice of parameters over which to optimise

![]() $M$

are

$M$

are

![]() $\kappa$

and

$\kappa$

and

![]() $\tau$

, it is easier to analyse the system by choosing to parameterise with

$\tau$

, it is easier to analyse the system by choosing to parameterise with

![]() $\kappa$

and

$\kappa$

and

![]() $\chi$

. This parametrisation is equivalent, so long as we note that some

$\chi$

. This parametrisation is equivalent, so long as we note that some

![]() $\kappa$

,

$\kappa$

,

![]() $\chi$

combinations may not be feasible. Specifically, any

$\chi$

combinations may not be feasible. Specifically, any

![]() $\kappa$

,

$\kappa$

,

![]() $\chi$

combination has a well-defined crime rate, and that crime rate, when combined with

$\chi$

combination has a well-defined crime rate, and that crime rate, when combined with

![]() $\chi$

gives a well-defined

$\chi$

gives a well-defined

![]() $\tau$

. However, for a given

$\tau$

. However, for a given

![]() $\kappa$

, there could exist two (or more) values

$\kappa$

, there could exist two (or more) values

![]() $\chi _1\lt \chi _2$

, with corresponding

$\chi _1\lt \chi _2$

, with corresponding

![]() $C_1\lt C_2$

that both give the same

$C_1\lt C_2$

that both give the same

![]() $\tau$

. As noted above, in such cases when a single

$\tau$

. As noted above, in such cases when a single

![]() $\tau$

gives rise to multiple crime rates, only the lowest rate is realisable, hence the combination

$\tau$

gives rise to multiple crime rates, only the lowest rate is realisable, hence the combination

![]() $\kappa$

,

$\kappa$

,

![]() $\chi _2$

is not feasible. While this could potentially be a problem moving forward, we note that this issue will not arise when

$\chi _2$

is not feasible. While this could potentially be a problem moving forward, we note that this issue will not arise when

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, and even when

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, and even when

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

, we can be sure that any

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

, we can be sure that any

![]() $\kappa$

with

$\kappa$

with

![]() $\chi \leq 1$

is feasible. This is because, when a single

$\chi \leq 1$

is feasible. This is because, when a single

![]() $\tau$

could yield multiple crime rates via (2.6), either one of those crime rates has

$\tau$

could yield multiple crime rates via (2.6), either one of those crime rates has

![]() $\chi \leq 1$

and the others have

$\chi \leq 1$

and the others have

![]() $\chi \gt 1$

, and the

$\chi \gt 1$

, and the

![]() $\chi \leq 1$

rate is the feasible one, or all of the crime rates have

$\chi \leq 1$

rate is the feasible one, or all of the crime rates have

![]() $\chi \gt 1$

. We will revisit this point later.

$\chi \gt 1$

. We will revisit this point later.

Seeking critical points of

![]() $M$

gives the following equations

$M$

gives the following equations

After some algebra, one can show that in order for there to exist a simultaneous solution to the equations above, it must be the case that

Note that since

![]() $\chi \gt 0,$

equation (3.19) requires either that

$\chi \gt 0,$

equation (3.19) requires either that

![]() $n\lt 1$

or that

$n\lt 1$

or that

![]() $n \gt \frac {1}{p}\gt 1$

in order for such a critical point to exist. The

$n \gt \frac {1}{p}\gt 1$

in order for such a critical point to exist. The

![]() $n\lt 1$

case always leads to

$n\lt 1$

case always leads to

![]() $f\gt 1$

and therefore should not be considered further. Assuming

$f\gt 1$

and therefore should not be considered further. Assuming

![]() $n\gt \frac {1}{p}$

, then

$n\gt \frac {1}{p}$

, then

![]() $\chi _o\lt 1$

, which means this is certainly a feasible point. However, we must still determine if

$\chi _o\lt 1$

, which means this is certainly a feasible point. However, we must still determine if

![]() $f=\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \chi _o\leq 1$

. This is automatically the case when

$f=\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \chi _o\leq 1$

. This is automatically the case when

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

; that is, when crime has a minimum at

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \lt 1$

; that is, when crime has a minimum at

![]() $C_*$

. However, if

$C_*$

. However, if

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then this requirement places an upper bound on

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then this requirement places an upper bound on

![]() $n$

for the existence of the critical point, such that

$n$

for the existence of the critical point, such that

![]() $n\lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p - \beta }$

.

$n\lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p - \beta }$

.

Assume for now that all requirements are met for a physically relevant

![]() $\chi _o$

. Let

$\chi _o$

. Let

![]() $FRP_o$

and

$FRP_o$

and

![]() $TPR_o$

be the false positive and true positive rates obtained when

$TPR_o$

be the false positive and true positive rates obtained when

![]() $\chi =\chi _o$

, and let

$\chi =\chi _o$

, and let

![]() $\Delta _o=TPR_o-FPR_o$

. Then any interior critical points are located at

$\Delta _o=TPR_o-FPR_o$

. Then any interior critical points are located at

![]() $(\kappa _o,\chi _o)$

, where

$(\kappa _o,\chi _o)$

, where

![]() $\kappa _o$

satisfies

$\kappa _o$

satisfies

which in general would have to be solved numerically for

![]() $\kappa _o$

. But, by considering the behaviour of the above expression as

$\kappa _o$

. But, by considering the behaviour of the above expression as

![]() $\kappa \to 0$

and

$\kappa \to 0$

and

![]() $\kappa \to \infty$

, we note that the above equation can be made to hold true at any

$\kappa \to \infty$

, we note that the above equation can be made to hold true at any

![]() $\kappa _o\gt 0$

by a careful choice of

$\kappa _o\gt 0$

by a careful choice of

![]() $\lambda$

. Further, these

$\lambda$

. Further, these

![]() $\lambda$

values become arbitrarily large as

$\lambda$

values become arbitrarily large as

![]() $\kappa _o\to 0$

and arbitrarily small (assuming boundedness of

$\kappa _o\to 0$

and arbitrarily small (assuming boundedness of

![]() $\Gamma$

at large arguments) as

$\Gamma$

at large arguments) as

![]() $\kappa _o\to \infty$

, so that any choice of

$\kappa _o\to \infty$

, so that any choice of

![]() $\lambda$

should yield at least one solution

$\lambda$

should yield at least one solution

![]() $\kappa _o$

.

$\kappa _o$

.

We now switch from

![]() $\chi$

to

$\chi$

to

![]() $FPR$

, and check the boundaries of the domain,

$FPR$

, and check the boundaries of the domain,

![]() $\kappa \in [0,\infty )$

and

$\kappa \in [0,\infty )$

and

![]() $FPR \in [0,\beta ]$

, to see whether the critical point(s) above are the only possibilities for a global minimum or not. If

$FPR \in [0,\beta ]$

, to see whether the critical point(s) above are the only possibilities for a global minimum or not. If

![]() $n\lt \frac {1}{p}$

, the next few lines will show that

$n\lt \frac {1}{p}$

, the next few lines will show that

![]() $M \to 0$

as

$M \to 0$

as

![]() $\kappa \to \infty$

in a particular way, leaving no global minimum. To get

$\kappa \to \infty$

in a particular way, leaving no global minimum. To get

![]() $M \to 0$

, we need both

$M \to 0$

, we need both

![]() $C$

and

$C$

and

![]() $\lambda \kappa ^n(1-C)FPR$

tending to zero. As a result, we need

$\lambda \kappa ^n(1-C)FPR$

tending to zero. As a result, we need

![]() $\kappa ^n FPR \to 0$

. For this to happen as

$\kappa ^n FPR \to 0$

. For this to happen as

![]() $\kappa \to \infty$

, we need

$\kappa \to \infty$

, we need

![]() $FPR \to 0$

. Now note that

$FPR \to 0$

. Now note that

![]() $TPR = \frac {\alpha }{\beta ^p}FPR^p$

. Since

$TPR = \frac {\alpha }{\beta ^p}FPR^p$

. Since

![]() $FPR\to 0$

and

$FPR\to 0$

and

![]() $p\lt 1$

,

$p\lt 1$

,

![]() $FPR^p \gg FPR$

. And so, for the requirement that

$FPR^p \gg FPR$

. And so, for the requirement that

![]() $C \to 0$

,

$C \to 0$

,

we need

![]() $\kappa ( \frac {\alpha }{\beta }FPR^p - FPR) \to \infty$

. In particular, we need

$\kappa ( \frac {\alpha }{\beta }FPR^p - FPR) \to \infty$

. In particular, we need

![]() $\kappa FPR^p \to \infty .$

Equivalently, we need

$\kappa FPR^p \to \infty .$

Equivalently, we need

![]() $(\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}}FPR)^p \to \infty$

which is true iff

$(\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}}FPR)^p \to \infty$

which is true iff

![]() $\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}}FPR \to \infty$

. Rearranged,

$\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}}FPR \to \infty$

. Rearranged,

So, since

![]() $\kappa ^nFPR \to 0,$

we need

$\kappa ^nFPR \to 0,$

we need

![]() $\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}-n} \to \infty$

in a way that satisfies (3.22). This condition can only be satisfied if

$\kappa ^{\frac {1}{p}-n} \to \infty$

in a way that satisfies (3.22). This condition can only be satisfied if

![]() $n \lt \frac {1}{p}$

, as claimed. As previously discussed, arbitrarily large punishments are not generally feasible, nor desired, so we will focus on the case where

$n \lt \frac {1}{p}$

, as claimed. As previously discussed, arbitrarily large punishments are not generally feasible, nor desired, so we will focus on the case where

![]() $n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

, where

$n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

, where

![]() $M\to \infty$

as

$M\to \infty$

as

![]() $\kappa \to \infty$

so long as

$\kappa \to \infty$

so long as

![]() $FPR\neq 0$

.

$FPR\neq 0$

.

When

![]() $FPR = 0,$

we have

$FPR = 0,$

we have

![]() $TPR = 0.$

In turn,

$TPR = 0.$

In turn,

![]() $\Delta = 0$

and therefore

$\Delta = 0$

and therefore

![]() $\kappa \Delta = 0.$

So,

$\kappa \Delta = 0.$

So,

Similarly when

![]() $\kappa = 0,$

$\kappa = 0,$

![]() $\kappa \Delta = 0$

and so,

$\kappa \Delta = 0$

and so,

![]() $C = C_{max}$

and

$C = C_{max}$

and

We note that by (3.17), when

![]() $\kappa =0$

and

$\kappa =0$

and

![]() $FRP\gt 0$

,

$FRP\gt 0$

,

![]() $\frac {\partial M}{\partial \kappa }\lt 0$

, indicating that

$\frac {\partial M}{\partial \kappa }\lt 0$

, indicating that

![]() $M=C_{max}$

cannot be the global minimum. Similarly, by (3.18), as

$M=C_{max}$

cannot be the global minimum. Similarly, by (3.18), as

![]() $FPR\to 0$

and

$FPR\to 0$

and

![]() $\kappa \gt 0$

,

$\kappa \gt 0$

,

![]() $\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\lt 0$

.

$\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\lt 0$

.

When

![]() $FPR = \beta$

then

$FPR = \beta$

then

![]() $TPR=\alpha$

and

$TPR=\alpha$

and

![]() $\Delta =\alpha -\beta$

, and there is at least one point

$\Delta =\alpha -\beta$

, and there is at least one point

![]() $\kappa =\kappa _\beta$

that could be a local minimum, which satisfies

$\kappa =\kappa _\beta$

that could be a local minimum, which satisfies

At the same time, at

![]() $(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

,

$(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

,

Note then that if

![]() $\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

, the case in which crime is minimised at

$\frac {p\alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

, the case in which crime is minimised at

![]() $C_*$

,

$C_*$

,

![]() $\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\gt 0$

at

$\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\gt 0$

at

![]() $(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

, and so this point is not a minimum. Alternatively, if

$(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

, and so this point is not a minimum. Alternatively, if

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, then

![]() $\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\gt 0$

and

$\frac {\partial M}{\partial FPR}\gt 0$

and

![]() $(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

is not a minimum when

$(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

is not a minimum when

![]() $n \lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

, which corresponds to the case in which the critical point(s)

$n \lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

, which corresponds to the case in which the critical point(s)

![]() $(\kappa _o,\chi _o)$

exist. The final possibility is that

$(\kappa _o,\chi _o)$

exist. The final possibility is that

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

and

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

and

![]() $n \gt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

, in which case there are no critical point(s)

$n \gt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

, in which case there are no critical point(s)

![]() $(\kappa _o,FPR_o)$

and there is a local minimum for at least one point

$(\kappa _o,FPR_o)$

and there is a local minimum for at least one point

![]() $(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

.

$(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

.

The above arguments lead to the following theorem:

Theorem 3.5.

When

![]() $n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

and either

$n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

and either

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

or

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta }\lt 1$

or

![]() $n \lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

there is a global minimum of

$n \lt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

there is a global minimum of

![]() $M$

in the interior of the domain at

$M$

in the interior of the domain at

![]() $(\kappa _o,FPR_o)$

. When

$(\kappa _o,FPR_o)$

. When

![]() $n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

,

$n \gt \frac {1}{p}$

,

![]() $\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, and

$\frac {p \alpha }{\beta } \geq 1$

, and

![]() $n \gt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

there is a global minimum of

$n \gt \frac {\alpha -\beta }{\alpha p-\beta }$

there is a global minimum of

![]() $M$

along the boundary at

$M$

along the boundary at

![]() $(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

. When

$(\kappa _\beta ,\beta )$

. When

![]() $n \lt \frac {1}{p},$

the objective function

$n \lt \frac {1}{p},$

the objective function

![]() $M \to 0$

as

$M \to 0$

as

![]() $\kappa \to \infty$

and

$\kappa \to \infty$

and

![]() $FPR \to 0$

in a particular way and

$FPR \to 0$

in a particular way and

![]() $M$

has no strict global minimum.

$M$

has no strict global minimum.

The above results indicate that a wide array of “optimal” justice systems occur based on the choice of

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $\lambda$

in (3.16). For example, a system with low

$\lambda$

in (3.16). For example, a system with low

![]() $C$

and high

$C$

and high

![]() $\tau$

is optimal with a very small value of

$\tau$

is optimal with a very small value of

![]() $\chi _o$

coupled with a somewhat large

$\chi _o$

coupled with a somewhat large

![]() $\kappa _o$

, indicating an

$\kappa _o$

, indicating an

![]() $n$

only slightly above

$n$

only slightly above

![]() $1/p$

and a relatively small

$1/p$

and a relatively small

![]() $\lambda$

. Alternatively, as

$\lambda$

. Alternatively, as

![]() $n \to \infty ,$

$n \to \infty ,$

![]() $\chi \to 1.$

This

$\chi \to 1.$

This

![]() $\chi$

corresponds to choosing

$\chi$

corresponds to choosing

![]() $\tau _*$

that solely minimises the crime rate as in Lemma 3.1, in which

$\tau _*$

that solely minimises the crime rate as in Lemma 3.1, in which

![]() $C_*=\tau$

. In other words, as the scaling of

$C_*=\tau$

. In other words, as the scaling of

![]() $M$

with

$M$

with

![]() $\kappa$

grows ever larger, the judge’s best course of action is in solely minimising the crime rate

$\kappa$

grows ever larger, the judge’s best course of action is in solely minimising the crime rate

![]() $C$

, and in this case it is not possible to have both a low

$C$

, and in this case it is not possible to have both a low

![]() $C$

and a high

$C$

and a high

![]() $\tau$

.

$\tau$

.

Figure 2 is a contour graph that shows the behaviour of the objective function

![]() $M$

in a numerical simulation. To construct this plot, for each threshold

$M$

in a numerical simulation. To construct this plot, for each threshold

![]() $\tau$

and punishment level

$\tau$

and punishment level

![]() $\kappa$

indicated, we solve the crime rate equation (equation (2.6)) and then compute the objective function

$\kappa$

indicated, we solve the crime rate equation (equation (2.6)) and then compute the objective function

![]() $M$

. In choosing the parameter values for the numerical simulation, we attempt to keep in mind what a reasonable society might have, though admittedly, the parameters chosen are not based on any empirical values. We choose

$M$

. In choosing the parameter values for the numerical simulation, we attempt to keep in mind what a reasonable society might have, though admittedly, the parameters chosen are not based on any empirical values. We choose

![]() $p = 0.2$

for our simulation, a case where the signals of the criminals and innocents are relatively easy to distinguish. We set the policing rate of criminals at

$p = 0.2$

for our simulation, a case where the signals of the criminals and innocents are relatively easy to distinguish. We set the policing rate of criminals at

![]() $\alpha = 0.8$

. Meanwhile, we set the policing rate of the innocents to be lower, at

$\alpha = 0.8$