Introduction

People with life-threatening illnesses may experience suffering in multiple dimensions: physical, psychological, social, and existential (Saunders Reference Saunders1964). This may be associated with clinical syndromes of anxiety, depression, demoralization, and a desire for hastened death (Nikoloudi et al. Reference Nikoloudi, Galanis and Tsatsou2025). These, in turn, relate to diminished quality of life, increased frequency and quantity of ER visits and hospitalizations, and suicide (Grobman et al. Reference Grobman, Mansur and Babalola2023; Sadowska et al. Reference Sadowska, Fong and Horning2023). Unfortunately, existing interventions often fail to adequately address the psychospiritual dimensions of suffering associated with a life-threatening illness. For instance, although antidepressants are widely prescribed to treat depressive and anxiety symptoms in individuals with advanced cancer, evidence for their efficacy in this population remains limited and inconsistent (Schimmers et al. Reference Schimmers, Breeksema and Smith-Apeldoorn2022; Vita et al. Reference Vita, Compri and Matcham2023). Psychotherapeutic approaches have likewise demonstrated only modest benefits for quality of life, sense of meaning, anxiety, and depression, and importantly, there are currently no FDA-approved treatments for existential distress (Grob et al. Reference Grob, Bossis, Griffiths, Carr and Steel2013; Schimmers et al. Reference Schimmers, Breeksema and Smith-Apeldoorn2022).

Psilocybin is the psychoactive ingredient in psilocybe cubensis, colloquially known as “magic mushrooms.” These fungi grow around the globe and were used by Mesoamerican civilizations as part of religious ceremonies and healing rituals (MacCallum et al. Reference MacCallum, Lo and Pistawka2022). More recently, psilocybin has garnered interest within Western medical practice for its promise in treating end-of-life distress, amongst other disorders (Agin-Liebes et al. Reference Agin-Liebes, Malone and Yalch2020; MacCallum et al. Reference MacCallum, Lo and Pistawka2022). While its mechanism of action remains incompletely understood, research suggests that psilocybin promotes cortical structural and functional neuroplasticity via activation of intracellular 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) 2A receptors (Vargas et al. Reference Vargas, Dunlap and Dong2023). Research suggests that psilocybin’s therapeutic effect may also be mediated in part by the dissolution of self-boundaries and the experience of a “mystical” state of consciousness, often characterized in North American literature by a sense of unity with a greater whole, positive mood, transcendence of space and time, and ineffability (Weiss et al. Reference Weiss, Roseman and Giribaldi2024). This leads to increased psychological flexibility and a sense of connection with nature, self, and others, engendering increases in positive attitudes about death, coherence, and life meaning (Shnayder et al. Reference Shnayder, Ameli and Sinaii2023). The patient’s expectations and mindset (often referred to as “set”) and therapeutic setting (specifically one in which they feel comfortable, safe, and supported) predict a more intense alteration of consciousness and protect against difficult psychological experiences, i.e., a “bad trip” (Carhart-Harris et al. Reference Carhart-Harris, Roseman and Haijen2018).

Psilocybin has emerged as a potential alternative to commonly utilized treatments for psychological distress related to life-threatening illness. Studies of patients with advanced-stage cancer who receive psilocybin-assisted therapy (PAT) have observed rapid, robust, and durable effects on measures of both depression and anxiety (Shelton and Hendricks Reference Shelton and Hendricks2016). In a 2024 study of patients with cancer, clinically significant effects remained constant or improved 8 weeks after a high-dose psilocybin session, with a mean 66% reduction in anxiety symptoms and a 50% depression remission rate amongst participants – a 2016 study demonstrated similar results sustained for at least 6 months (Agrawal et al. Reference Agrawal, Richards and Beaussant2024; Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Johnson and Carducci2016).

Since 5 January 2022, Health Canada’s Special Access Program (SAP) permits prescribing psilocybin for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions when conventional treatments have failed or are unsuitable. Approvals are granted on a case-by-case basis, providing legal access to the prescriber or their delegated health care professional without specifying the exact setting of administration. As such, one may receive this treatment at home (Health Canada 2023).

Methods

A 51-year-old man with metastatic lung cancer since 2021 was referred to an outpatient palliative care clinic in February 2022 with a prognosis of less than 6 months. He was originally diagnosed with a squamous cell carcinoma of the nasal vestibule in 2017 which led to a total rhinectomy and permanent disfigurement. He was successfully treated for anxiety and depression using sertraline and cognitive behavioral therapy after his initial diagnosis, but these treatments were ineffective following his cancer recurrence. His referral to PC came in conjunction with resignation from his job due to medical disability, and a feeling of what he described as “free falling.” The patient reported symptoms of anxiety and depression to his original psychologist at the cancer center, which he believed were undergirded by what he described as a loss of control. He did not express suicidality and initially wanted to die a natural death. However, with increasing physical and psychospiritual suffering, he eventually decided to schedule Medical Aid in Dying (MAID) for his next birthday, approximately 6 months later. Disease progression in his lung subsequently necessitated the insertion of a chest tube, resulting in significant pain and discomfort and opening the possibility of having MAID sooner in the event of intolerable suffering. Despite increasing sertraline to 100 mg and ongoing psychotherapy, he continued to experience a constant state of anguish, death anxiety, and despair. Secondary to this poor response and having learned about the possibility of PAT through his palliative care physician, he expressed interest in pursuing this treatment. When disease-modifying treatments were concluded, the patient moved to his rural lakeside cottage to live out his last days, receiving support from his wife and from palliative homecare services. He expressed interest in undergoing PAT in this location as it was the place where he felt most comfortable and at ease.

The psilocybin was authorized through the SAP and shipped to the hospital pharmacy by an approved third-party supplier. SSRIs were considered contraindicated with psilocybin at the time due to concerns for serotonin syndrome. For this reason, and because they were also causing side effects, they were stopped several weeks prior to PAT. A consulting psychiatrist joined the treatment team and established a diagnosis of major depressive disorder with anxious distress. He offered the patient 3 preparatory sessions modelled on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). These sessions focused on mindfulness practices, emotional exploration, and reducing experiential avoidance – specifically targeting the ACT processes of present-moment awareness, acceptance, and cognitive defusion (Ruiz Reference Ruiz2010). The patient was encouraged to notice and let go of attempts to control internal experiences and to approach difficult emotions and thoughts with openness. Eight weekly integration sessions based on the same ACT components were planned for after the psilocybin session.

Non–home-care settings (palliative-care residence and outpatient clinic) were explored; however, given the patient’s strong preference for being outside the city and his entreaty that receiving care there was deeply meaningful to him, treatment at his rural cottage was selected to optimize privacy, comfort, and set/setting. Synthetic psilocybin at a dose of 25 mg was administered orally in the company of his palliative care physician and psychiatrist, who chose a nondirective psychotherapeutic approach. The dosing took place in a bedroom with a hospital bed set up. We had previously agreed that his wife could remain onsite for the session without any direct engagement unless needed, but she was eventually asked to leave the kitchen area as her activities were distracting to the session close by. Over the course of the experience, the patient requested to move to his living room and later outdoors, where he sat facing the lake. Music via both headphones and speakers as well as an eye mask were offered, but the patient ultimately decided to spend most of the session without them and in direct conversation with the physicians. A broad range of topics were brought up by the patient and discussed amongst the 3, some of which had profound significance as stated below.

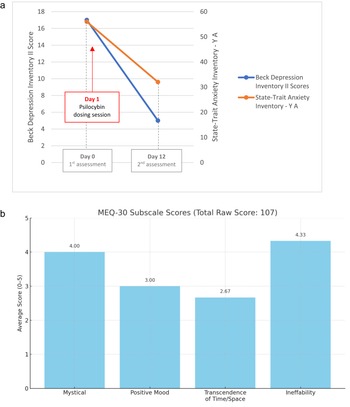

There were no adverse events reported. Depression and anxiety were measured using commonly validated scales both pre- and post-treatment via the Beck’s Depression Inventory II (BDI) and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y A (STAIYA) (Smarr and Keefer Reference Smarr and Keefer2011; Spielberger et al. Reference Spielberger, Gorsuch and Lushene1983) and the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ) was self-reported 1 day post-treatment (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Johnson and Griffiths2015).

With the patient’s consent, the dosing session was audio-recorded for documentation and accuracy. All patient quotations included in the result section are transcribed verbatim from the recorded session.

Results

During the first hour of the psilocybin session, the patient reported an increase in pain despite taking his regular extended-release and breakthrough doses of hydromorphone as planned. After nearly 30 minutes of guided somatic psychotherapeutic practices, he reported being able to “disconnect” from the pain and expressed a desire to relocate from the bedroom to the house’s screened-in porch, from which he could see the lake and hear the wind in the trees. The patient then reported significant visual changes while having a “mystical experience” (Figure 1b for MEQ), accompanied by intense catharsis and emotional relief. He discussed his family dynamics, romantic relationships, and his connection with animals (his pet cat was present for most of the time): “I no longer feel the pain; I feel that I am flying, flying over my body … I know that the doors will close soon, that this is my last opportunity to say or do the things that are important to me, to express this pain and grief that I have not been able to express, to communicate to others…”

Figure 1. (a) Evolution of the Beck Depression Inventory II and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y A before and after psilocybin dosing session. (b) Mystical Experience Questionnaire according to subscales.

He further described the session as a consolidation of long-held insights: “This experience is not a revelation, but the manifestation of all my thoughts and realizations.”

Finally, he articulated a sense of perspective and acceptance:

Life is a lesson in humility; I arrived with zero, I leave with zero… Everything has a meaning, nothing is created, nothing is lost. I need to stop resisting.

Measurements taken 11 days after the psilocybin session for BDI were reduced from 17 to 5 (from “mild” to “absent or minimal” depression), and those for STAIYA from 56 to 32 (from “high” to “no or low” anxiety) (Figure 1a). Integration ended after the fifth week according to the patient’s wish to spend more of the time he had left with friends and family. The patient reported an easing of his overall suffering persisting at least 2 months after administration of psilocybin. He continued to describe an improved sense of spirituality and connection to his environment, and his wife observed an improved mood and reduced irritability. The patient ultimately decided to have MAID nearly 3 months after psilocybin treatment due to poorly controlled physical pain and respiratory issues. The day before his MAID date, he reached out to the team to express his gratitude for having done the therapy and how meaningful he had found it, stating he had wished it was done sooner so that he had the necessary time to deal with what had come up.

Discussion

This case report describes PAT for a patient with advanced cancer who had transitioned from hospital care at an academic center to home-based palliative care in a rural community. In this case, PAT provided effective and rapid amelioration of his symptoms. Administering psilocybin in the patient’s home allowed him to undergo the treatment in a comfortable and safe environment, an important consideration when emphasizing the paramount role of set and setting in PAT (Pronovost-Morgan et al. Reference Pronovost-Morgan, Greenway and Roseman2025; Roseman et al. Reference Roseman, Nutt and Carhart-Harris2018).

This context is particularly relevant in light of emerging literature on compassionate access to psilocybin in Canada, which has highlighted that not all patients report positive experiences (de la Salle et al. Reference de la Salle, Kettner and Lévesque2024). Our case suggests that tailoring the treatment to individual needs – including selecting a meaningful, peaceful setting – may enhance therapeutic outcomes (Hartogsohn Reference Hartogsohn2017). Providing PAT in the patient’s rural cottage, described as his “sanctuary,” likely contributed to the sense of safety, openness, and depth of the experience.

Despite his profoundly spiritual experience, unrelenting pain, physical suffering and loss of autonomy led him to schedule MAID 3 months after his PAT. He reported that he was more at ease with the idea of death than before PAT, which brings up the discussion of whether a patient’s demoralized state can compromise their capacity to give consent for MAID (Kissane Reference Kissane2004). This case supports the idea of access to PAT for appropriate patients when access to MAID has been granted, whether it ends up changing their decision or not (Byock Reference Byock2018; Rosenblat and Li Reference Rosenblat and Li2021). The patient remained grateful for PAT until the end and wished he could have started the therapeutic journey sooner (Farzin Reference Farzin2023). This was the first case of PAT under the SAP in QC, and the palliative care, PAT, and MAID were all delivered to the patient’s rural country cottage and billed under the public healthcare system. With potentially increased availability of psilocybin as it is considered for broadened regulatory approval, PAT could become a viable option for managing psychospiritual distress in palliative care and hospice patients. Furthermore, as more and more patients are treated at-home, future work could include creating practice guidelines and considerations for home-based PAT.

To augment a growing body of evidence from randomized controlled trials, we recommend a prospective-case series examining differences in outcomes for PAT between homecare versus various clinical settings to understand the benefits and challenges inherent to each. Such a study could clarify differences in outcome, including potential differences in adverse events. The number of integration sessions necessary to achieve a meaningful reduction in psychospiritual symptoms following psilocybin treatment also bears further study given the patient’s sustained remission after 5 integration sessions, the scarcity of time for many advanced cancer patients, and the limited availability of competent providers (i.e., clinicians with appropriate training and supervision in psychedelic-assisted therapy, including competencies related to safety, ethical practice, and the psychospiritual dimensions of care) (Phelps Reference Phelps2017). How PAT changes patient perception of MAID, and decisions with respect to the same, also bears further investigation (Poppe et al. Reference Poppe, Bublitz and Repantis2025). Overall, discerning the importance of these different variables to clinical outcomes will help determine how PAT can be implemented at scale for this patient population.

Acknowledgments

In loving memory of M.K., who braved the unknown and paved the way for others. We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to his beloved wife and extended family who supported him until the end.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec (AUDACE program).

Competing interests

Houman Farzin is the founder of Mystic Health and an investor in Beckley Psytech. He is a trainer for the non-profit organization TheraPsil and was a volunteer member of their training and ethics committees. He also served as a site physician in Montréal for MAPPUSX, a Phase 3 clinical trial of MDMA-AT for PTSD sponsored by Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelics Studies (MAPS).