Impact statement

Anticipating future demand is of paramount importance for equitable and sustainable management of water resources, particularly in the context of accelerating climate change and socioeconomic transformations. This article presents a comprehensive and methodologically rigorous review of water demand modeling approaches, with a particular focus on their applicability across socioeconomic sectors (municipal, agricultural, industrial, commercial, and institutional) and spatial scales (municipality, watershed, and region). At the heart of the study is the introduction of the STAR framework (System, Trouble/Treatment, Alternative, Response), which provides a clear and innovative roadmap for conducting literature reviews in environmental sciences and beyond. In addition to this framework, the article presents: (a) a new indicator of parsimony relevant for methods selection based on available data, (b) a new classification framework for existing methods and (c) a hybrid modeling workflow aiming to enhance water management and governance decisions supported by an open-source geospatial web software architecture. Due to its flexible design, the proposed workflow and underlying software architecture have potential applications that extend well beyond the field of water management and the nexus approaches, making it a valuable tool for addressing various environmental issues.

Introduction

Freshwater is an essential but limited natural resource that plays a fundamental role in socioeconomic development. Its demand is set to grow considerably in the upcoming decades, making it a highly coveted resource (Hertel and Liu, Reference Hertel and Liu2016). Thus, its availability and management are becoming increasingly critical challenges, especially in the context of prevailing factors such as climate change and socioeconomic growth. These water-demand drivers (Kulshreshtha, Reference Kulshreshtha1993; Huber et al., Reference Huber, Rüdisser, Meisch, Stotten, Leitinger and Tappeiner2021; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Ouyang, Wang, Wu and Guo2023) have already led to numerous usage conflicts among economic sectors worldwide (Roson et al., Reference Roson, Damania, Damania and Dahan2015; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Mu, Jamnani, Hafeez and Gao2020; Rondeau-Genesse et al., Reference Rondeau-Genesse, Caron, Audet, Da Silva, Tarte, Parent, Comeau and Matte2024).

The undesirable situations mentioned above arise, for example, from changes in precipitation patterns and rising temperatures that affect the spatiotemporal availability of water, particularly for agricultural irrigation and industrial uses (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ren, Ouyang, Feng, Tao, Granger and Poudel2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang, Shahid, Xie, Du, Shang and Zhang2018; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Dong, Jin, He, Yin and Chen2023). While future climate projection scenarios anticipate an increase in water stress (Rowshon et al., Reference Rowshon, Dlamini, Mojid, Adib, Amin and Lai2019; Egerer et al., Reference Egerer, Puente, Peichl, Rakovec, Samaniego and Schneider2023; Guemouria et al., Reference Guemouria, Chehbouni, Belaqziz, Epule Epule, Brahim, El Khalki, Dhiba and Bouchaou2023), the extent and timing of water scarcity will vary regionally, primarily due to different socioeconomic assumptions (Shen et al., Reference Shen, Oki, Utsumi, Kanae and Hanasaki2008). In such a context, future water demand models are often used as planning tools to implement effective adaptation and mitigation strategies. By anticipating future water demands of every economic sector, it is possible to promote equitable and sustainable access to water resources, at different spatial scales. Thus, we argue that a multisector and multiscale approach to water demand modeling would help shape public policies and ensure well-balanced allocations of resources in response to future climatic and socioeconomic conditions.

Recent water conflicts in the province of Quebec (Canada) have raised important concerns regarding future water demand (Bernier and Forcier-Martin, Reference Bernier and Forcier-Martin2025; Gerbet and Dépelteau, Reference Gerbet and Dépelteau2025), given anticipated climate disruptions due to the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, on the one hand, and the productivity of the province’s various economic sectors in response to demographic and economic growth, on the other hand. In this context, the Ministry of Environment, the Fight Against Climate Change, Wildlife and Parks and Ouranos commissioned a participatory research project named ProjectEau to strengthen its ability to anticipate future water demand across five key economic sectors, that is, municipal, agricultural, industrial, commercial and institutional. The goal is to propose a methodological water demand projection framework that: (a) reflects the specificities of Quebec’s economic activities, (b) integrates both environmental and socio-economic drivers of the demand and (c) is applicable at several spatial scales, from municipalities to watersheds, with the flexibility of being extended across the entire province. The first phase of the project involved a literature review on existing water demand projection methods to propose a suitable framework for Quebec’s socioeconomic sectors given readily accessible data.

Water demand is often analyzed at multiple spatial scales ranging from an urban point of view (city or municipality) to a watershed and regional or national one (Bijl et al., Reference Bijl, Biemans, Bogaart, Dekker, Doelman, Stehfest and van Vuuren2018). Each scale brings together several economic sectors, that is, municipal/residential, institutional, commercial and even industrial, which are interconnected. For instance, at the watershed, regional and national scales, these water use sectors often co-exist with additional water uses, such as for agricultural production and energy production (Baccour et al., Reference Baccour, Tilmant, Albiac, Espanmanesh and Kahil2025). Although these sectors can be identified separately, they are interdependent, particularly from a practical point of view. For example, the water is often withdrawn from the same source, a river, lake or aquifer, which, de facto, creates interactions, but also tensions, and sometimes real conflicts over access to the resource (Gharib et al., Reference Gharib, Arabi, Goemans, Manning and Maas2024; Hall et al., Reference Hall, Whittemore, Padowski, Yourek, Yorgey, Rajagopalan, McLarty, Scarpare, Liu, Asante-Sasu, Kondal, Brady, Gustine, Downes, Callahan and Adam2024). Such a co-existence of multiple sectors within one spatial scale of interest often requires a balanced, optimal distribution and consumption of available water resources. The methodological approaches culminate in what is called the nexus approaches (Endo et al., Reference Endo, Yamada, Miyashita, Sugimoto, Ishii, Nishijima, Fujii, Kato, Hamamoto, Kimura, Kumazawa and Qi2020; Molajou et al., Reference Molajou, Afshar, Khosravi, Soleimanian, Vahabzadeh and Variani2023), relevant to the understanding and management of the complex interdependencies between, for example, water, food, energy, land and ecosystems (Kebede et al., Reference Kebede, Nicholls, Clarke, Savin and Harrison2021; Alamanos et al., Reference Alamanos, Koundouri, Papadaki and Pliakou2022). These studies have all indicated that by anticipating future water demands of every economic sector within an integrated framework, it is possible to promote equitable and sustainable access to water resources at different spatial scales. Thus, we argue that the modeling of a multisector, multiscale approach to water demand would contribute to shape fair public policies and ensure well-balanced allocations of resources in response to future climatic and socioeconomic conditions.

An examination of current literature reviews on future water demand modeling methods, including univariate, econometric regression, end-use, system dynamics, agent-based and computational intelligence models, reveals several important limitations. In general, the focus is on a single economic sector (e.g., municipal or industrial) or climatic factors alone, thus failing to account for the combined and even compound influence of climatic and socioeconomic conditions on water demand (Potopová et al., Reference Potopová, Trnka, Vizina, Semerádová, Balek, Chawdhery, Musiolková, Pavlík, Možnỳ, Štěpánek and Clothier2022; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023; Mazzoni et al., Reference Mazzoni, Alvisi, Blokker, Buchberger, Castelletti, Cominola, Gross, Jacobs, Mayer, Steffelbauer, Stewart, Stillwell, Tzatchkov, Yamanaka and Franchini2023). Accordingly, several reviews have overlooked the full range of interactions within and between sectors (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Fox, McKenney and Parkin2019; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ding, Shao, Xu, Jiao, Luo and Yu2017; Fiorillo et al., Reference Fiorillo, Kapelan, Xenochristou, De Paola and Giugni2021). This parochial view of existing literature review efforts does not expose the complex dynamics of drivers such as population growth, urbanization, economic development, technological advancements, agricultural practices, cultural practices and policy changes that often compromise the effectiveness of water management strategies. Again, we argue that a more systemic view of water demand modeling methods is therefore essential to overcome these limitations and support the development of more robust water demand management strategies.

This article addresses the limitations of current literature reviews on future water demand modeling methods discussed above by contributing to: (a) a more comprehensive analysis of current modeling approaches and (b) an integrated workflow that captures intra and inter-sectoral interactions. In addition, it introduces a comprehensive streamlined approach for conducting literature reviews in environmental sciences. At the core of this approach is the STAR (Systems, Trouble/Treatment, Alternative, Response) framework (Celicourt et al., Reference Celicourt, Drapeau, Lovince, Azima, Thiaw, Louis, Célicourt, Mertilus, Louis, Said, Chery, Petit-Homme, Pierre, Rousseau, Kabore and Gumiere2025), a methodology guiding our formulation of research questions and literature search strategy. In addition, we used the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; Page et al., Reference Page, Moher and McKenzie2022; Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009), a framework providing a structured process for identifying, selecting, appraising and synthesizing studies from the literature. Furthermore, it presents a data-requirement-based metric, as well as a new nomenclature for classifying the methods and approaches surveyed, and ultimately to guide the selection of modeling methods. Finally, it proposes a hybrid methodological workflow made up of three core modeling components: computational intelligence, dynamic systems and probabilistic scenarios. The proposed workflow ensures broad applicability, making it adaptable not only to water demand management but also to a wide range of challenges in environmental sciences.

The article is organized as follows: the following section outlines the methodology adopted for this review; the third and fourth sections present the results and discussions, respectively. The later examines the strengths, limitations, and similarities between the identified methods. The final section concludes with a summary of the different methods for modeling future water requirements and our recommendations for future research.

Methods

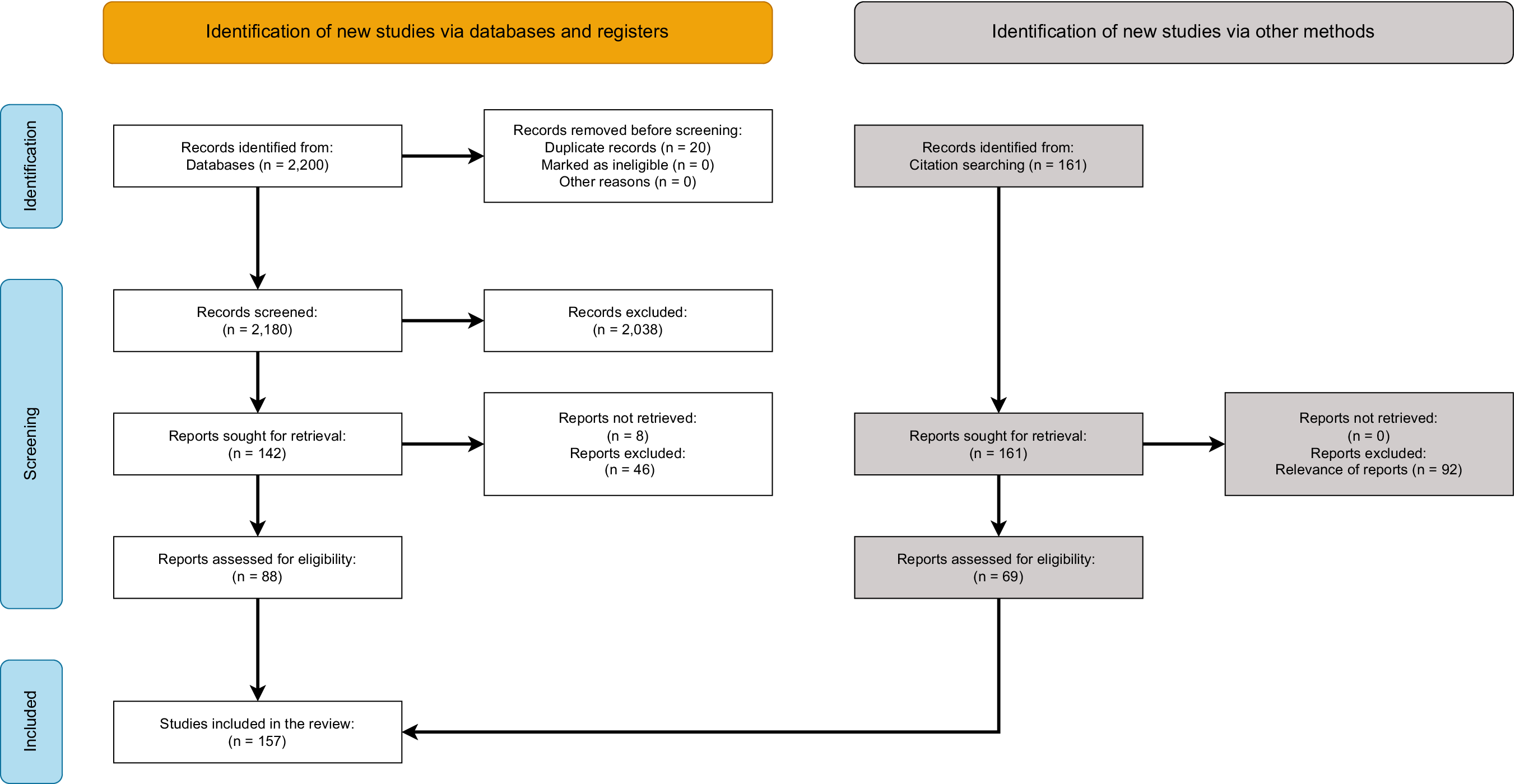

To carry out the literature review, we adopted a structured methodological approach to (a) reduce potential biases related to the publications selection and (b) facilitate the reproducibility of the reported results. To this end, we first selected the PRISMA framework (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; Page et al., Reference Page, Moher and McKenzie2022) recognized for enabling high-quality systematic reviews in the biomedical field. It consists of a checklist of 27 essential elements to integrate in review or meta-analysis reports, as well as a four-phase workflow (identification, selection, eligibility and inclusion) for the selection of relevant studies.

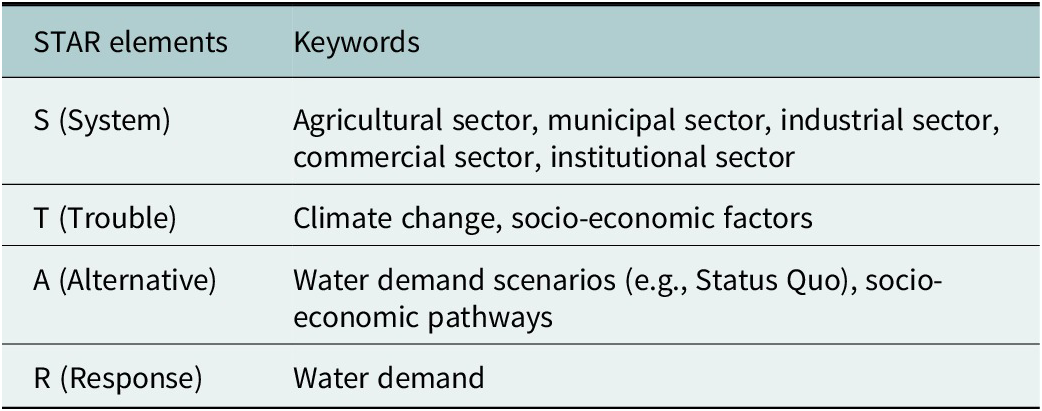

Although the PRISMA framework aims for a true representation of the available knowledge addressed by a research question, it does not elaborate procedures for: (a) crafting research questions and (b) searching the references in the bibliographic databases. These tasks require the application of, respectively, the CIMO (context, intervention, mechanism, outcome; Denyer et al., Reference Denyer, Tranfield and Van Aken2008) and the PICO (population/patient/problem, intervention, comparison/control, outcome; Methley et al., Reference Methley, Campbell, Chew-Graham, McNally and Cheraghi-Sohi2014; Palaskar, Reference Palaskar2017). However, PICO and CIMO are designed for applications in biomedical and institutional management research settings, respectively. Thereby, they are limited in effectiveness and scope particularly because elements of some review questions cannot be explicitly mapped to the PICO structure (James et al., Reference James, Randall and Haddaway2016). Thus, they are unable to accommodate the complexity of socio-environmental systems. The STAR framework (Celicourt et al., Reference Celicourt, Drapeau, Lovince, Azima, Thiaw, Louis, Célicourt, Mertilus, Louis, Said, Chery, Petit-Homme, Pierre, Rousseau, Kabore and Gumiere2025), by design, embodies a broader perspective on literature search and research questions formulation problems specific to the environmental sciences domain. Hence, we have selected it as the most appropriate approach for our review. The elements of the framework and keywords sample used to define our literature search strategy are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Initial STAR-structured keywords used as criteria for our literature search strategy and research questions formulation

From the STAR criteria, two research questions were formulated to support the objective of our proposed review:

-

a. How are environmental and socioeconomic factors modeled in current methods and approaches for sectoral water demand projection?

-

b. How parsimonious are the current methods and approaches for future sectoral water demand modeling when considering the influence of both environmental and socioeconomic factors?

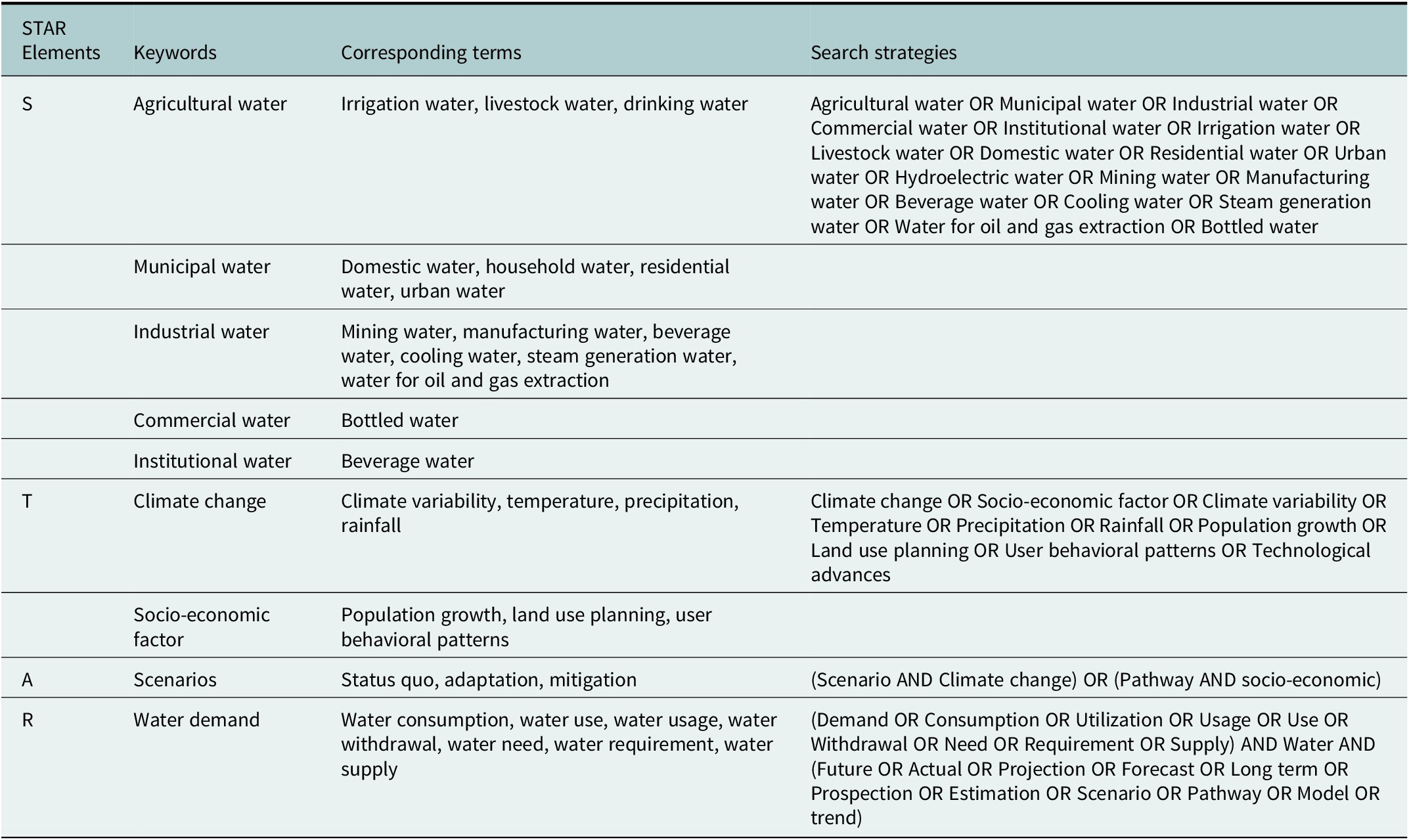

Because of the complexity of our literature review subject, we further defined a more exhaustive list of keywords along with the queries formulated using Boolean operators introduced in Table 2. A targeted search with the keywords or boolean equations was performed in scientific databases like Web of Science, Engineering Village, Scopus, Google Scholar and Proquest Dissertation, to identify the relevant literature. This first step yielded a total of 1,924 references. A snowball sampling approach (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Scott, Geddes, Atkinson, Delamont, Cernat, Sakshaug and Williams2019), complemented by Google search engine and bibliographic management software such as Mendeley, was also employed. It involves the identification of relevant sources from an initial set of key references, then exploring the references cited therein to find further relevant documents. This process is repeated as new sources are found, gradually broadening the search. This non-systematic search yielded 256 additional references for a total of 2,180 articles, book chapters, conference reports, and theses.

Table 2. Summary of the research strategy adopted

Note: The keywords of the second and third columns are selected and grouped according to, depending on the STAR element in question, the sector (municipal, agricultural, etc.) or the driver (climatic or socioeconomic). For each element of the STAR framework, we provide a single Boolean equation that is tested against the bibliographic databases to obtain articles relevant to answer the two research questions of the review.

In Table 3, we define eligibility criteria for selecting the references of relevance to answer our research questions. This assessment of the collected references was conducted in a two-step process, according to the prescriptions of the PRISMA method, that is, based on (a) their titles and abstracts and (b) the full text.

Table 3. Summary table of inclusion and exclusion criteria used for references screening

Our article search and selection processes, summarized in Figure 1, resulted in the inclusion of 157 articles, book chapters, theses, and technical reports.

Figure 1. The PRISMA diagram summarizing our references selection process.

Results

The modeling processes of future water demand rely on a variety of methodological approaches, adapted to the time scales and sectors of economic activities concerned. Here, we report our findings along four main lines: (1) the fundamental methods for which we propose a degree of parsimony metric that reflects the methods complexity and their data requirements, (2) more sophisticated or hybrid approaches resulting from the extension and compounding of the core methods, (3) the uncertainty assessment approaches and (4) the water demand drivers.

A common denominator of the identified methods is the time scale which often influences the reliability as well as the robustness of informed decisions. From a temporal scale standpoint, methods fall into three broad categories, that is, short, medium, and long term (Billings, Reference Billings2008; Donkor et al., Reference Donkor, Mazzuchi, Soyer and Roberson2014; Rinaudo, Reference Rinaudo, Grafton, Daniell, Nauges, Rinaudo and Chan2015). Short-term methods (less than a year) are generally used by municipalities and water supply agencies for operational planning, that is, pump scheduling, system load balancing, and guaranteeing continuous water supply, in order to manage seasonality and peak water needs, among other things. Medium-term methods (from 1 to 10 years) are used for tactical planning to drive medium-term investment decisions, such as building new wells, increasing storage, or upgrading treatment facilities. Long-term methods (beyond 10 years) are developed for strategic planning, which supports the anticipation of structural, technological and political impacts on water demand to, for example, identify future sources, prepare for population growth and adapt to climate change. These categories of methods are represented with orange color in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Diagram summarizing the different methods and approaches used to classify future water demand estimation methods. Concentric circles represent increasing levels of specificity: core methodological categories (inner ring), subcategories (middle ring) and detailed components or applications (outer rings).

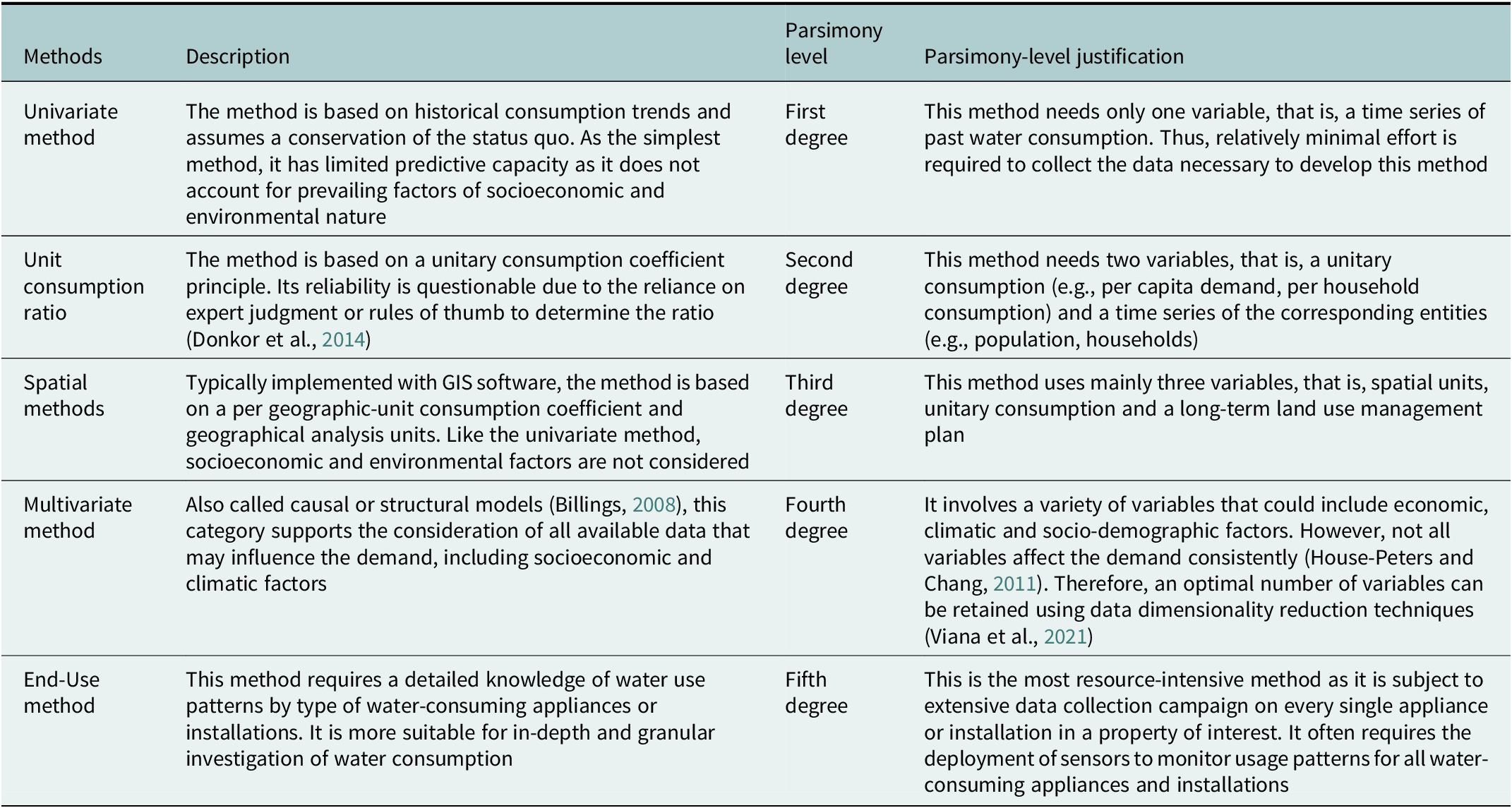

Classes of foundational methods using a degree of parsimony indicator

From an analytical standpoint, we identified the five main categories of water demand modeling methods summarized in Table 4 (Billings, Reference Billings2008; Donkor et al., Reference Donkor, Mazzuchi, Soyer and Roberson2014; Rinaudo, Reference Rinaudo, Grafton, Daniell, Nauges, Rinaudo and Chan2015). A notable difference among these methods is what could be called the ‘dimensional heterogeneity’, which refers to the variability in the number of dimensions or variables required to execute them. We therefore capitalize on this type of heterogeneity to spin off an indicator, a degree of parsimony, to rank these methods and at the same time, answer our second research question. The proposed indicator is defined in terms of the number of variables necessary, the operations (calculations) required to create these variables, and the perceived or anticipated effort in terms of human and computing resources deployment required to support the data acquisition. Accordingly, for a same number of variables, two methods may have different degrees of parsimony if, for example, more resources (calculations, time, mathematical operations) are required to obtain or create the data for one or the other method. In Table 4, we associate the indicator to each of the categories and justify as to why the corresponding degree is attributed. These methods are also represented with the blue color in Figure 2.

Table 4. Summary of the foundational methods for future water demand modeling and their classification according to the proposed degree of parsimony indicator

Advanced water demand modeling methods

Multiple hybridizations of foundational methods are often performed along with more advanced analytical techniques to capture certain complexities in water demand modeling. For instance, we distinguished:

-

a. Soft methods or computational intelligence methods (CIMs), which could be considered as a subset of the multivariate method, are subdivided into three temporal-scale classes, that is, short, medium and long terms. However, despite their predictive accuracy and their independence from statistical assumptions, they are mainly applied to short-term modeling situations (Adamowski et al., Reference Adamowski, Chan, Prasher, Ozga-Zielinski and Sliusarieva2012; Mouatadid and Adamowski, Reference Mouatadid and Adamowski2017; Muhammad et al., Reference Muhammad, Li, Feng, Zhai, Chen and Zhu2019). This category is in orange color in Figure 2.

-

b. Single-sector and multisector modeling methods that integrate tailored variables and spatial resolution to model water demand of specific economic sectors. These methods are often integrated in dedicated software tools (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Martin and Heaney2009; Hejazi et al., Reference Hejazi, Edmonds, Clarke, Kyle, Davies, Chaturvedi, MarshallWise, Eom, Calvin, Moss and Kim2014; Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015). Under this category, we group the econometric methods specific to, for example, the industrial sector represented in yellow in Figure 2.

-

c. The analytical-performance-based methods classification by House-Peters and Chang (Reference House-Peters and Chang2011), depicted in gray color in Figure 2, distinguishes six classes of methods based on criteria such as: (a) spatial resolution considered, (b) temporal resolution of the data, (c) linear and nonlinear relationships modeling in the data, (d) dynamic modeling (e.g., system dynamics models, agent-based models) of the processes and (e) quantification of uncertainty sources and magnitudes in the data and the analyses. In the next subsection, we present a detailed description of the latest subcategory of methods.

It is worth highlighting that the assessment of the methods uncertainty, especially for long-term projections of water demand, has given rise to even more complex methods enabled by the continuous improvement in computational power and data collection (Herrera et al., Reference Herrera, Marazuela and Hofmann2022). As uncertainties can lead to systems being oversized – resulting in increased costs – or undersized and cause constraints on use in times of shortage as well as opportunity costs (Rinaudo, Reference Rinaudo, Grafton, Daniell, Nauges, Rinaudo and Chan2015) and ultimately to system failure (Mijic et al., Reference Mijic, Dobson and Liu2024), the quantification of uncertainties in water demand models become even more necessary for tactical and strategic planning.

Approaches to uncertainty assessment and treatment in water demand modeling methods

Two main approaches have been proposed to deal with uncertainties in future-water-demand modeling methods: (a) the contrasting scenarios approach (Cosgrove, Reference Cosgrove2013; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Schoups and Van de Giesen2013; Sivagurunathan et al., Reference Sivagurunathan, Elsawah and Khan2022) and (b) the stochastic or probabilistic approach (Qi and Chang, Reference Qi and Chang2011; Alhendi et al., Reference Alhendi, Al-Sumaiti, Elmay, Wescaot, Kavousi-Fard, Heydarian-Forushani and Alhelou2022).

The contrasting scenarios approach

Scenarios are narratives developed according to a logical framework that explain how events might unfold (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1997). According to the case study presented by Cosgrove (Reference Cosgrove2013), the Shell company initially developed the scenario-based approach to forecast long-term availability of fossil resources around 50 years ago. However, its use as a water resource management tool, to guide policymaking and decision-making, only emerged in the late 1990s. The uncertainty associated with the evolution of climatic and socio-economic conditions is one of the main reasons for applying the contrasting scenario approach to water (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Schoups and Van de Giesen2013). From a methodological point of view, we distinguish and define two generations of scenario-based approaches.

-

a. The first generation comprises scenarios developed without a reference framework. This category covers the spectrum from an idiosyncratic method to an approach using at most one reference scenarios framework, that is, with consideration of environmental factors alone or socioeconomic factors alone or policy assumptions alone. Here, we refer to those scenarios proposed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the climate change research community which include: the long-term GHG emission scenarios (SA90, IS92, and the Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES); Nakicenovic et al., Reference Nakicenovic, Alcamo, Gerald Davis, Fenhann, Gaffin, Gregory, Grubler, Jung, Kram, Rovere EL, Michaelis, Mori, Morita, Pepper, Pitcher, Price, Riahi, Roehrl, Rogner, Sankovski, Schlesinger, Shukla, Smith, Swart, Rooijen, Victor and Zhou2000; Moss et al., Reference Moss, Edmonds, Hibbard, Manning, Rose, Van Vuuren, Carter, Emori, Kainuma, Kram, Meehl, Mitchell, Nakicenovic, Riahi, Smith, Stouffer, Thomson, Weyant and Wilbanks2010); the representative concentration pathways (RCPs; Van Vuuren et al., Reference Van Vuuren, Edmonds, Kainuma, Riahi, Thomson, Hibbard, Hurtt, Kram, Krey, Lamarque, Masui, Meinshausen, Nakicenovic, Smith and Rose2011); the shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs; O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Kriegler, Riahi, Ebi, Hallegatte, Carter, Mathur and Van Vuuren2014; O’Neill et al., Reference O’Neill, Kriegler, Ebi, Kemp-Benedict, Riahi, Rothman, Van Ruijven, Van Vuuren, Birkmann, Kok, Levy and Solecki2017; Kriegler et al., Reference Kriegler, O’Neill, Hallegatte, Kram, Lempert, Moss and Wilbanks2012) and the shared climate policy assumptions (SPAs; Kriegler et al., Reference Kriegler, Edmonds, Hallegatte, Ebi, Kram, Riahi, Winkler and Van Vuuren2014). Studies by Neale et al. (Reference Neale, Carmichael and Cohen2007) and Liu (Reference Liu2020) in Canada, Boland (Reference Boland1997) and Sanchez et al. (Reference Sanchez, Terando, JordanWSmith, RWagner and Meentemeyer2020) in the United States, Grouillet et al. (Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015) in France and Spain and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Yu, Sun and Liu2023) and Dang et al. (Reference Dang, Zhang, Yao, Mu, Lyu, Zhang and Zhang2024) in China fall under this category.

-

b. The second generation encompasses those realized according to a set of the aforementioned reference scenarios framework integrated into a comprehensive multi-dimensional framework with consideration for quantitative and/or qualitative analyses. The need for this category of scenarios has been raised since the beginning of the 21st century by Vorosmarty et al. (Reference Vorosmarty, Green, Salisbury and Lammers2000), Alcamo et al. (Reference Alcamo and Gallopín2009), and Moss et al. (Reference Moss, Edmonds, Hibbard, Manning, Rose, Van Vuuren, Carter, Emori, Kainuma, Kram, Meehl, Mitchell, Nakicenovic, Riahi, Smith, Stouffer, Thomson, Weyant and Wilbanks2010), who advocated for a more holistic perspective to the scenarios built at finer geographical scales (local, watershed and regional) to account for external factors capable of inducing changes at these scales. We noticed a scant application of this category of scenarios to assess the impacts of global change on water resources, and more specifically on water demand. Hanasaki et al. (Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013) were certainly the first to develop qualitative and quantitative scenarios compatible with climate forcing rates (RCP) and future socioeconomic conditions (SSP) for projecting the water consumption of several sectors of economic activity (agricultural, industrial and municipal) at a global scale. At the same scale, Arnell and Lloyd-Hughes (Reference Arnell and Lloyd-Hughes2014) estimated the impacts of climate change on water scarcity and river flood frequencies in 2050 and 2080, under different combinations of SSPs and RCPs. Fujimori et al. (Reference Fujimori, Hanasaki and Masui2017) estimated the future water abstraction of the industrial sector, again on a global scale, using SSPs with or without SPAs. Yao et al. (Reference Yao, Tramberend, Kabat, Hutjes and EWerners2017) carried out water consumption projections for the industrial, agricultural and domestic sectors of the Pearl River Delta economic zone (regional scale) in China using SSPs and RCPs. Giuliani et al. (Reference Giuliani, Lamontagne, Hejazi, Reed and Castelletti2022) assessed the long-term impacts of climate change mitigation policies linked to land-use change emissions on local water demands in several watersheds in southern and western Africa. Alizadeh et al. (Reference Alizadeh, Adamowski and Inam2022) used SSPs in conjunction with RCPs to create local-scale narrative frames as part of an iterative participatory process to quantify, among other things, the water demand of the agricultural sector in Pakistan.

The stochastic or probabilistic approach

The scenario-based approach suffers from three major limitations: (a) the limited number of quantitative scenarios considered, (b) the implicit and incomplete characterization of uncertainties and (c) the lack of transparency in the implementation of expert judgment procedures (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Schoups and Van de Giesen2013; Sivagurunathan et al., Reference Sivagurunathan, Elsawah and Khan2022). The probabilistic approach addresses the first two limitations by extending the range of possible scenarios based on a repeated execution of forecasting models either with a random variation of input parameters(sensitivity analysis) or according to predefined statistical distribution functions. Examples of studies that apply this approach include the following. In the United States, Hazen and Sawyer (Reference Hazen and Sawyer2004) developed the Long-Term Demand Forecasting System tool used by the Tampa Bay Water operator in Southwest Florida to forecast regional water demand, and Lee et al. (Reference Lee, AWentz and Gober2010) produced long-term water consumption maps using Bayes’ Maximum Entropy geostatistical model for the city of Phoenix in Arizona. Haque et al. (Reference Haque, Rahman, Hagare and Kibria2014) implemented a Monte Carlo simulation to quantify long-term water demand using three future climate scenarios (A1B, A2 and B1 from the SRES framework) and four distinct levels of water restrictions (an implicit SPA) in the Blue Mountains region, in Australia. Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Shi, Yu, Li, Wang and Zhou2016) proposed a framework for probabilistic prediction of urban water consumption and uncertainty estimation in a context of incomplete information in China. Bobojonov et al. (Reference Bobojonov, Berg, Franz-Vasdeki, Martius and Lamers2016) developed a stochastic optimization model to study the impact of climate change (SRES) on farm income and efficiency of water use in western Uzbekistan. Rasifaghihi et al. (Reference Rasifaghihi, Li and Haghighat2020) undertook a stochastic approach to forecasting water consumption under the combined influence of driving variables and climate change (RCP framework) for the city of Montreal, Canada. Sharafati et al. (Reference Sharafati, Asadollah and Shahbazi2021) quantified the relationship between the uncertainty of climate variable projections (RCP) made using a framework incorporating a stochastic model and the variability of water demand for the city of Neyshabur, Iran.

Complementarity of the scenario-based and stochastic approaches

This literature review revealed a remarkable absence of probabilistic models in scenario-based water demand estimation, especially when considering the second-generation scenarios mentioned above. However, the probabilistic approach makes it possible to attach a probability to each of the variables or factors (climatic and socio-economic) of a scenario, or on the other end, a sensitivity analysis can be considered in the event of difficulty in specifying probability distributions. Thus, for each scenario, a range of values within which future water demand is likely to evolve is computed. We found two examples of publications that underscore the inclusiveness and complementarity of the scenario-based and stochastic water demand modeling approaches to form a probabilistic-scenarios approach: Qi and Chang (Reference Qi and Chang2011) who used a system dynamics and regression model to test, through sensitivity analysis, the impact of a variation in layoff rates on water demand in Manatee County, Florida, USA, and Donkor et al. (Reference Donkor, Mazzuchi, Soyer and Roberson2014) who proposed a probabilistic framework based on the Bayesian method to support the implementation of more robust water resource planning and management scenarios. We hypothesize that a probabilistic-scenarios approach would deliver a more credible and reliable future water demand to operators or stakeholders in the water sector.

Water demand drivers

Drivers of water demand can be classified into five major categories according to the elements of the STEEP (social, technology, economic, environmental and political factors) framework (Hammoud and Nash, Reference Hammoud and Nash2014): (a) social factors (e.g., population), (b) technological factors (e.g., water use efficiency), (c) environmental factors (e.g., natural: precipitation, temperature; physical: household size, household density, crop type, cultivated area), (d) economics (e.g., household income, water prices) and (e) political factors (e.g., operating or withdrawal permits) (Grafton et al., Reference Grafton, Ward, To and Kompas2011; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023; Mazzoni et al., Reference Mazzoni, Alvisi, Blokker, Buchberger, Castelletti, Cominola, Gross, Jacobs, Mayer, Steffelbauer, Stewart, Stillwell, Tzatchkov, Yamanaka and Franchini2023; Costa et al., Reference Costa, Meireles and Sousa2024). Although these drivers or factors do not influence the different economic sectors in the same way (as illustrated in Supplementary Appendix 1–4), the per capita water demand parameter (social factor) is often used in practice as a universal variable for domestic/residential/municipal, ICI sectors, and losses in water distribution networks (Renzetti, Reference Renzetti2002; Vaughan et al., Reference Vaughan, Crutcher, Labatt, McMahan, Bradford and Cluck2012).

Urban/municipal/residential water demand drivers and modeling methods

We need to highlight that the residential/municipal/urban sector is the most studied among the five economic sectors of interest in this article. For instance, a number of researchers such as Arbués et al. (Reference Arbués, Garcıa-Valiñas and Martınez-Espiñeira2003), Inman and Jeffrey (Reference Inman and Jeffrey2006), Corbella and Saurí i Pujol (Reference Corbella and Saurí i Pujol2009), House-Peters and Chang (Reference House-Peters and Chang2011), Bich-Ngoc and Teller (Reference Bich-Ngoc, Teller, Gervasi, Murgante, Misra, Stankova, Torre, Rocha, Taniar, Apduhan, Tarantino and Ryu2018), Abu-Bakar et al. (Reference Abu-Bakar, Williams and Hallett2021), and Cominola et al. (Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023) have carried out literature reviews on the different methods for estimating residential/urban/municipal water demand as well as the influencing factors. Among the others, the use of the univariate method was not observed, which would be due to the growth of more sophisticated methods to accommodate the complexity of climatic and socio-economic factors affecting demand since the 1990s. It was at this time that washing machines, dishwashers and swimming pool installations began to become ubiquitous in homes (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Sversvold, Wilcut and Keen2016). However, end-use methods (Boland, Reference Boland1997; Makki et al., Reference Makki, Stewart, Beal and Panuwatwanich2015; Sharvelle et al., Reference Sharvelle, Dozier, Arabi and Reichel2017; Mostafavi et al., Reference Mostafavi, Shojaei, Beheshtian and Hoque2018; Liu, Reference Liu2020), unit consumption ratio (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Ding, Shao, Xu, Jiao, Luo and Yu2017; Reference Wang, Yu, Sun and Liu2023), multivariate statistics (e.g., Neale et al., Reference Neale, Carmichael and Cohen2007; Ashoori et al., Reference Ashoori, Dzombak and Small2017; Parkinson et al., Reference Parkinson, Johnson, Rao, Jones, van Vliet, Fricko, Djilali, Riahi and Flörke2016; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yu, Sun and Liu2023) and spatial methods (Boland, Reference Boland1997; Neale et al., Reference Neale, Carmichael and Cohen2007; Sharvelle et al., Reference Sharvelle, Dozier, Arabi and Reichel2017) are those that are commonly found in the literature. A variety of emerging approaches have addressed the growing urgency of understanding and predicting the impacts of climate change and changing socio-economic conditions on municipal water demand and management, as well as informing the adoption of advanced scientific approaches by water service providers, public authorities, and decision-makers. These include the computational intelligence approach (e.g., Liu, Reference Liu2020; Mumbi et al., Reference Mumbi, Li, Bavumiragira and Fangninou2021; Fu et al., Reference Fu, Sun, Hoang, Yuan and Butler2023; Loucks, Reference Loucks2023; Zolghadr-Asli et al., Reference Zolghadr-Asli, Ferdowsi and Savić2024), system dynamics (e.g., Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li, Ahmad, Chen and Pan2013; Chang et al., Reference Chang, Liu, Bao, Chen and Wang2015; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Cai, Xu, Tan and Xu2019; Liu, Reference Liu2020), the scenario approach (e.g., Boland, Reference Boland1997; Neale et al., Reference Neale, Carmichael and Cohen2007; Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Gan, Yi, Qin and Lu2022) and the probabilistic approach (e.g., Monte Carlo simulation; Haque et al., Reference Haque, Rahman, Hagare and Kibria2014).

As per the determinant of water demand, social, environmental and economic factors remain the most relevant ones. Of the social factors, population plays a predominant role and is calculated using a variety of mathematical models (see Supplementary Appendix 1). A wide range of quantitative and qualitative variables that influence residential water demand are found in the literature. For instance, important social variables include population, education level, age, gender, tenure, immigration rate (House-Peters and Chang, Reference House-Peters and Chang2011; Bich-Ngoc and Teller, Reference Bich-Ngoc, Teller, Gervasi, Murgante, Misra, Stankova, Torre, Rocha, Taniar, Apduhan, Tarantino and Ryu2018; Abu-Bakar et al., Reference Abu-Bakar, Williams and Hallett2021; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023); environmental (natural) variables include precipitation, temperature, evapotranspiration (lawn watering) and wind speed (House-Peters and Chang, Reference House-Peters and Chang2011; Abu-Bakar et al., Reference Abu-Bakar, Williams and Hallett2021); economic variables include water price, household income, property value, Gross Domestic Product and water metering (Arbués et al., Reference Arbués, Garcıa-Valiñas and Martınez-Espiñeira2003; House-Peters and Chang, Reference House-Peters and Chang2011; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Schoups and Van de Giesen2013; Bich-Ngoc and Teller, Reference Bich-Ngoc, Teller, Gervasi, Murgante, Misra, Stankova, Torre, Rocha, Taniar, Apduhan, Tarantino and Ryu2018; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Yu, Sun and Liu2023); environmental (physical) variables include household size, household density, number of bedrooms, garden or lawn area, presence of swimming pools (Makki et al., Reference Makki, Stewart, Beal and Panuwatwanich2015; Bich-Ngoc and Teller, Reference Bich-Ngoc, Teller, Gervasi, Murgante, Misra, Stankova, Torre, Rocha, Taniar, Apduhan, Tarantino and Ryu2018; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023); variables concerning technological advances include the rate of equipment with hydro-economical appliances, the water-use efficiency of appliances, landscaping (Neale et al., Reference Neale, Carmichael and Cohen2007; Cominola et al., Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023); and political variables include water conservation policies, tariff structure (billing frequency), regulations (Corbella and Saurí i Pujol, Reference Corbella and Saurí i Pujol2009; House-Peters and Chang, Reference House-Peters and Chang2011; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Schoups and Van de Giesen2013; Abu-Bakar et al., Reference Abu-Bakar, Williams and Hallett2021).

Beyond the classification of the determinants according to the STEEP framework (Hammoud and Nash, Reference Hammoud and Nash2014), Abu-Bakar et al. (Reference Abu-Bakar, Williams and Hallett2021) introduced a triadic classification of the determinants as: (a) endogenous factors, that is, those directly influencing water demand (e.g., affluence, education, occupation, tenure), (b) exogenous factors, defined as those beyond the water consumer’s control (e.g., migration, tourism, rainfall, water availability) and (c) psychosocial factors (e.g., users’ intentions towards water use). Cominola et al. (Reference Cominola, Preiss, Thyer, Maier, Prevos, Stewart and Castelletti2023) proposed a closely similar classification based on the similarities of variables into: (a) observable determinants, that is, observable endogenous determinants (e.g., sociodemographic, property characteristics), (b) latent or psychosocial determinants (e.g., perception, habits) and (c) external or exogenous determinants (water price, temperature and precipitation).

Agricultural water demand drivers and modeling methods

In contrast to the several literature reviews on the residential water sector available in the literature, we have only found a few that partially cover, the agricultural water demand realm. These focus on: (a) the modeling of evapotranspiration used to calculate crop water demand (Wanniarachchi and Sarukkalige, Reference Wanniarachchi and Sarukkalige2022), (b) the cascading effect of climate change impacts on water availability and crop yield (Anwar et al., Reference Anwar, Liu, Macadam and Kelly2013), (c) precision irrigation scheduling (Gu et al., Reference Gu, Qi, Burghate, Yuan, Jiao and Xu2020; Abioye et al., Reference Abioye, Hensel, Esau, Elijah, Abidin, Ayobami, Yerima and Nasirahmadi2022; Bwambale et al., Reference Bwambale, Abagale and Anornu2022), (d) the impact of drinking water quality on livestock production (Tulu et al., Reference Tulu, Gadissa and Hundessa2023; Tulu et al., Reference Tulu, Hundessa, Gadissa and Temesgen2024) and (e) the economics of agricultural water management (Dudu and Chumi, Reference Dudu and Chumi2008).

Agricultural water demand is generally a function of (a) environmental factors (e.g., physical: irrigated area, crop types, livestock types; natural: temperature, precipitation, solar radiation), (b) economic factors (e.g., water price, producer profit), (c) technological factors (e.g., irrigation system efficiency) and (d) social factors (e.g., demographic evolution, consumption habits, lifestyle) (see Supplementary Appendix 3). It comes down to estimating the demand of its two key components, that is, irrigation and livestock (Hanasaki et al., Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013; Hejazi et al., Reference Hejazi, Edmonds, Clarke, Kyle, Davies, Chaturvedi, MarshallWise, Eom, Calvin, Moss and Kim2014; Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Tramberend, Kabat, Hutjes and EWerners2017; Agrawal et al., Reference Agrawal, Patrick, Davis, Ahiduzzaman and Kumar2022; Alizadeh et al., Reference Alizadeh, Adamowski and Inam2022; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Zhang, Yao, Mu, Lyu, Zhang and Zhang2024; Younis and Davies, Reference Younis and Davies2024). In some cases, water for product washing (Lehto et al., Reference Lehto, Sipilä, Alakukku and Kymäläinen2014; Vergine et al., Reference Vergine, Salerno, Libutti, Beneduce, Gatta, Berardi and Pollice2017) and facility cleaning (Drastig et al., Reference Drastig, Palhares, Karbach and Prochnow2016; Krauß et al., Reference Krauß, Drastig, Prochnow, Rose-Meierhöfer and Kraatz2016; Younis and Davies, Reference Younis and Davies2024) are also accounted for. It is worth highlighting that some researchers argue that farmers’ water use decisions are generally insensitive to variations in water prices (Scheierling et al., Reference Scheierling, Loomis and Young2006; Fraiture and Perry, Reference Fraiture, Perry, Molle and Berkoff2007 and that the price elasticity of water demand can vary depending on the type of crop (Pathak et al., Reference Pathak, Adusumilli, Wang and Almas2022). Some studies have considered demography as one of the key variables influencing agricultural water demand, as population and agricultural production are positively related (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li, Ahmad, Chen and Pan2013).

For instance, irrigation water demand for field crops is estimated from a minimum of five key variables (Döll and Siebert, Reference Döll and Siebert2002; Hanasaki et al., Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Ouyang, Wang, Wu and Guo2023). These include (a) irrigated area, (b) crop evapotranspiration calculated as a function of potential evaporation and a cultural coefficient, (c) effective rainfall, (d) the plant’s irrigation water use efficiency coefficient or the irrigation system efficiency and (e) irrigation intensity or crop density. For greenhouse crops, the amount of water allocated is generally estimated from global radiation, implying that water demand is generally equivalent to crop evapotranspiration (Incrocci et al., Reference Incrocci, Thompson, Fernandez-Fernandez, De Pascale, Pardossi, Stanghellini, Rouphael and Gallardo2020). It should be emphasized that evapotranspiration represents a critical variable in estimating agricultural water demand whether in greenhouses or in fields, for which at least a dozen nonspatial and spatial models have been developed (Prenger et al., Reference Prenger, Fynn and Hansen2002; Fazlil-Ilahil, Reference Fazlil-Ilahil2009; Katsoulas and Stanghellini, Reference Katsoulas and Stanghellini2019; Ghiat et al., Reference Ghiat, Mackey and Al-Ansari2021; Yan et al., Reference Yan, Acquah, Zhang, Wang, Zhang and Darko2021; Mokhtari et al., Reference Mokhtari, Sadeghi, Afrasiabian and Yu2023). In some studies, especially on a large or medium scale, vegetation indices, such as leaf area index, and normalized difference vegetation index are also used as proxies or substitutes to estimate evapotranspiration (Paul et al., Reference Paul, Rajib, Negahban-Azar, Shirmohammadi and Srivastava2021; Mokhtari et al., Reference Mokhtari, Sadeghi, Afrasiabian and Yu2023). In the context of climate projections, irrigation water demand is typically estimated as a function of temperature variation and rainfall variation (distribution and frequency), with averages spanning long time series. For example, Dang et al. (Reference Dang, Zhang, Yao, Mu, Lyu, Zhang and Zhang2024) estimated irrigation water demand as a function of precipitation and actual water use. These projection methods have evolved over the last three decades from simple statistical models (regression of socioeconomic variables; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Tramberend, Kabat, Hutjes and EWerners2017) to hydrological and plant growth models such as CropWat and WaterGAP (Döll and Siebert, Reference Döll and Siebert2002; Hanasaki et al., Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013; Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Zhang, Yao, Mu, Lyu, Zhang and Zhang2024) to the second-generation scenarios mentioned above (Hejazi et al., Reference Hejazi, Edmonds, Clarke, Kyle, Davies, Chaturvedi, MarshallWise, Eom, Calvin, Moss and Kim2014; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Tramberend, Kabat, Hutjes and EWerners2017; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Ouyang, Wang, Wu and Guo2023).

For livestock water demand, studies consider the biological characteristics (large livestock, small livestock, growth stage) and physiological requirements (basic water requirements) of the animals, as well as ancillary demands (hygiene, for example). More specifically, studies define water use quotas (unit consumption ration method) for large and small livestock (Hejazi et al., Reference Hejazi, Edmonds, Clarke, Kyle, Davies, Chaturvedi, MarshallWise, Eom, Calvin, Moss and Kim2014; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Cai and Zheng2018; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Cai, Xu, Tan and Xu2019). For aquaculture, evaporation, infiltration and precipitation are considered (Mauri et al., Reference Mauri, Pandey, Giuliani and Castelletti2022).

Institutional, commercial and industrial water demand drivers and modeling methods

The literature specific to future-water-demand estimation of the ICI sectors is remarkably limited. These three sectors represent a heterogeneous group of water consumers whose demand has historically been calculated using the unit consumption ratio method with water use coefficients derived from the number of employees and/or the number of occupants in the organization (Morales et al., Reference Morales, Heaney, Friedman and Martin2011; Brière, Reference Brière2012; Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015). However, due to the fragmentation and heterogeneity of these sectors, as well as the uniqueness of the facilities and processes implemented by customers, the unit consumption ratio method proves to be very deficient (Frost et al., Reference Frost, Sversvold, Wilcut and Keen2016), particularly in accessing information to differentiate the types of use. To circumvent this problem, Morales et al. (Reference Morales, Heaney, Friedman and Martin2011) proposed a new approach based on a water use coefficient constructed from publicly accessible heated/air-conditioned area and building water consumption data for the state of Florida, USA. Sharvelle et al. (Reference Sharvelle, Dozier, Arabi and Reichel2017) introduced the Integrated Urban Water Management GIS software for projecting municipal water demand, which categorizes ICI sectors into a single category and determines the demand for each ICI user in a spatial unit by averaging all ICI uses and the number of dwellings in that unit. This strategy transforms the method into a kind of unit consumption ratio.

To estimate industrial water demand, we have noted that a range of specific models or approaches have been developed, which we present in Supplementary Appendix 4. Of these, some are based on the organization’s output or production and a ratio of consumption per unit of production or added value (Grouillet et al., Reference Grouillet, Fabre, Ruelland and Dezetter2015; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Cai, Xu, Tan and Xu2019). Methods often consider the water demand according to industry type, that is, manufacturing, power generation, oil production and mining (Brière, Reference Brière2012; Flörke et al., Reference Flörke, Kynast, Bärlund, Eisner, Wimmer and Alcamo2013; Younis and Davies, Reference Younis and Davies2024). Flörke et al. (Reference Flörke, Kynast, Bärlund, Eisner, Wimmer and Alcamo2013) proposed two statistical models for calculating water demand for manufacturing and cooling thermoelectric power plants. For hydroelectricity generation in Quebec, Canada, from water storage dams, Agrawal et al. (Reference Agrawal, Patrick, Davis, Ahiduzzaman and Kumar2022) proposed a unit consumption ratio of 14 m3/MWh of electricity generated based on net evaporation. This ratio is, of course, dependent on climatic conditions, and for this purpose, Strachan et al. (Reference Strachan, Svehla, Heusler and Kersken2016) reported coefficients for different countries such as Austria, the United States and Norway. It should be highlighted that the work mentioned earlier is limited to estimating water demand without a consideration of the impact of climatic and socio-economic changes. In this context, for thermoelectric production, Hanasaki et al. (Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013) proposed a linear regression model for the industrial sector with the following parameters: (a) the amount of energy produced, (b) the intensity of water use and (c) an efficiency coefficient.

Second-generation scenarios (SSP/RCP; high, medium and low efficiency) have been developed around the efficiency coefficient used by Hanasaki et al. (Reference Hanasaki, Fujimori, Yamamoto, Yoshikawa, Masaki, Hijioka, Kainuma, Kanamori, Masui, Takahashi and Kanae2013). For instance, Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Davies and Liu2019) developed the Bow River Integrated Model based on a system dynamics model for the projection of water demand for several sectors (industrial, agricultural, municipal, environmental, and recreational) and several of its subcategories under the influence of climate conditions (RCP) and water management policies (SPA) in Alberta (Canada). Yao et al. (Reference Yao, Tramberend, Kabat, Hutjes and EWerners2017) used a model developed by Flörke et al. (Reference Flörke, Kynast, Bärlund, Eisner, Wimmer and Alcamo2013) based on enterprise’s value added and a coefficient of technological change or efficiency to project water consumption in the manufacturing sub-sector using second-generation scenarios (SSP and RCP). Fujimori et al. (Reference Fujimori, Hanasaki and Masui2017) proposed a regression model to estimate water withdrawal for several subsectors of the industrial sector including pulp and paper, textiles, mining, food processing, using second-generation scenarios consisting in SSP and SPA.

Discussion

This literature review aims to gather knowledge about existing water demand estimation methods to guide the selection of an appropriate one that considers future climatic and socioeconomic conditions. Based on our literature search strategy, we review methods developed since the 1990s using a streamlined methodological approach supported by a juxtaposition of the PRISMA and STAR frameworks. This is an important contribution of the article beyond the reported results as prior to STAR, literature search in environmental sciences were mostly conducted without an enabling systematic framework. Instead, a collection of keywords and ‘regular expressions’ structured as Boolean equations is generally used, an ad hoc approach that is prone to produce incomplete and inconsistent literature search results.

As another important contribution, we had developed an indicator of the level of parsimony of the foundational methods in relation to the number of variables required and the anticipated effort for data acquisition. This enabled the consideration of multivariate statistical methods as the most appropriate class of methods to accommodate the current level of complex interactions between climatic, economic, sociodemographic, technological, political and geospatial factors likely to influence water demand of a country’s economic sectors. The results indicate that the adoption of this family of methods has become very common due to the increasing availability of both temporal and spatial data. However, we noticed a strong emphasis on some sort of unit consumption coefficient (fixed or time-varying) for water demand entities (e.g., population, crop, domestic installations) considered in all economic sectors studied. That coefficient forms the basis of the overall method or approach (e.g., end-use, multivariate statistics, scenarios) applied. Such a strategy simplifies the data collection and processing processes and the implementation of the estimation method or the development of demand projection scenarios.

Data availability has also enabled progress to be made in modeling the relationships between variables of a particular sector (intrasector) or between variables from different sectors (intersector). For example, we have noted that population is a cross-cutting variable in the sense that methods for estimating water demand in all economic sectors use or depend on it (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Li, Ahmad, Chen and Pan2013; Sharvelle et al., Reference Sharvelle, Dozier, Arabi and Reichel2017). It should be highlighted that despite the recognition of the influence of population or estimating water demand in all economic sectors, this relationship has not been explicitly translated into a model for the agricultural sector. Nevertheless, we found that population (sociodemographic factor) alone cannot influence the expansion of irrigated areas, but economic factors must also be considered (Sauer et al., Reference Sauer, Havlík, Schneider, Schmid, Kindermann and Obersteiner2010; Puy, Reference Puy2018; Puy et al., Reference Puy, Piano and Saltelli2020). Often such socio-demographic and economic factors may exist beyond the local agricultural production context, especially when considering concept like virtual water, which accounts for the embedded water used in the production of goods across geographical regions (Chen and Chen, Reference Chen and Chen2013).

The relationships of sectoral or cross-sectoral variables are increasingly modeled using historical data and computational intelligence methods. This notable traction of the so-called data-driven models in water and environmental engineering has also been observed by Zolghadr-Asli et al. (Reference Zolghadr-Asli, Ferdowsi and Savić2024). This family of methods has proven their ability to reveal non-linear relationships between dependent (output) and independent (input) variables, without the need for traditional statistical assumptions. Such relationships are validated by statistical techniques used to estimate prediction errors before they are implemented in long-term simulation models (Liu, Reference Liu2020).

To implement long-term water demand projection, some studies coupled computational intelligence methods with a system dynamics (SD) model. This is becoming a modern approach that stands out from other approaches aiming at an integrated modeling of environmental and socioeconomic factors that govern the evolution of economic sectors, with feedback loops. More importantly, the SD model makes it possible to consider political factors that may influence water demands, hence, to produce more accurate projections (Qi and Chang, Reference Qi and Chang2011). As demonstrated by the analysis of Kelly et al. (Reference Kelly, Jakeman, Barreteau, Borsuk, ElSawah, Hamilton, Henriksen, Kuikka, Maier, Rizzoli, van Delden and Voinov2013) as well as by results presented in Supplementary Tables 5–8 (in Supplementary Appendix), the SD modeling technique is rapidly gaining ground, especially in the field of integrated water management. A notable example of the implementation of this hybrid approach in long-term projection scenarios is that of Liu (Reference Liu2020).

Although, the hybrid approach of computational intelligence and system dynamics models holds great promise for more robust long-term water demand projections, the results of this literature review also revealed that the modeling chain would be incomplete without taking into account uncertainties in the data and/or in the projection results. To this end, the contrasting scenarios approach and the stochastic or probabilistic approach have been proposed, which we discussed in this article. We argue that these approaches are inclusive and complementary. Hence, a probabilistic scenarios approach based on a sensitivity analysis would allow the advantages of both uncertainty-based approaches to be exploited. An extension of the computational intelligence and SD components with a probabilistic scenarios component would lead to an even more comprehensive workflow for future water demand estimation. Such a methodological framework is, therefore, positioned to support sustainable water resources management in highly complex social and ecological systems settings.

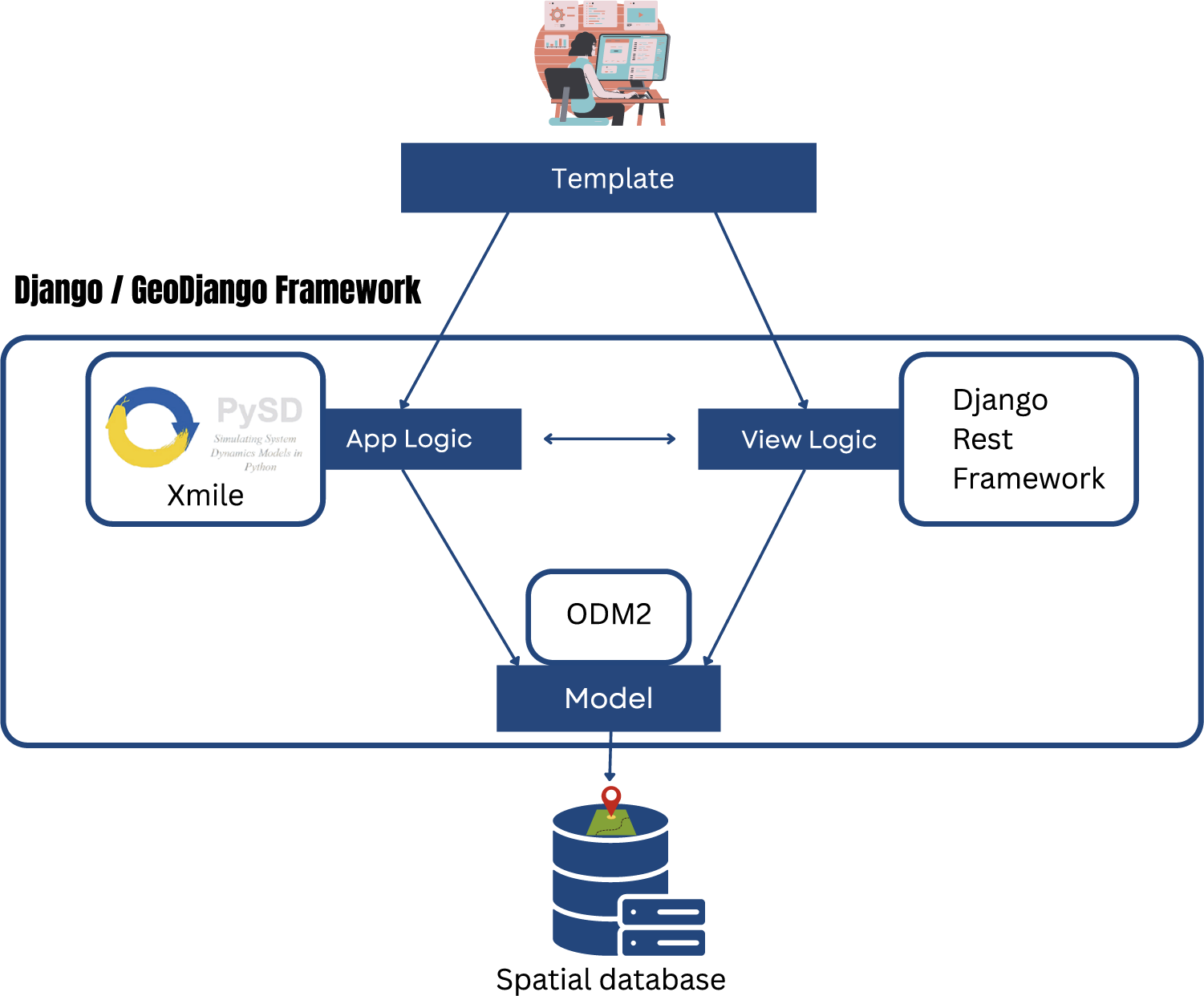

This discussion of future water demand estimation methods and approaches leads us to recommend a hybrid approach made up of three modeling components: computational intelligence, SD, and second-generation probabilistic scenarios. As House-Peters and Chang (Reference House-Peters and Chang2011) suggest, this proposal appears to represent an approach halfway between the parsimony of traditional methods and the high complexity of emerging methods. Advances in the open-source software movement, including the publication of source codes and libraries created using high-level programming languages such as Python, have improved the accessibility for the implementation of the proposed approach. For instance, the development of the PySD library (Houghton and Siegel, Reference Houghton and Siegel2015; Martin-Martinez et al., Reference Martin-Martinez, Samsó, Houghton and Ollé2022; Toba and Nguyen, Reference Toba and Nguyen2022) as well the XMILE standard file format for SD models (Eberlein and Chichakly, Reference Eberlein and Chichakly2013; Gadewadikar and Marshall, Reference Gadewadikar and Marshall2024) make it possible to completely program and run an SD model in a Python development environment, without the use of commercial software systems. Here, we present the architecture of a web-based geographic information system implemented with the Python programming language that integrates the components of the proposed approach (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A proposed representative software workflow for the implementation of multisectoral and multifactorial projections of future water demand based on the Django, GeoDjango, Django REST Framework libraries ecosystem as well as the PySD library.

The proposed workflow, powered by a spatial database that implements the observations data model (Horsburgh et al., Reference Horsburgh, Aufdenkampe, Mayorga, Lehnert, Hsu, Song, Jones, Damiano, Tarboton, Valentine, Zaslavsky and Whitenack2016), also caters to the requirement of extensive qualitative and quantitative knowledge that encompasses stakeholder views and perspectives, time series and spatial socioeconomic and climatic data (Giupponi et al., Reference Giupponi, Balabanis, Cojocaru, Vázquez and Mysiak2024). However, the proposed method as well the accompanying workflow are theoretical in nature and have not been evaluated to fully weigh their technical expertise requirements. In addition, its consideration of the integration of system dynamics models in a geographic information system environment, that is, spatial system dynamics, makes it an apparently sophisticated method. But, when implemented at the watershed level where, for example, at least two economic sectors co-exist, that is, municipal and agricultural, the method can integrate scenario-based land use/land cover projection models, which is relevant to anticipate spatiotemporal water demand dynamics. The method can also incorporate future water availability (supply) data in the form of climatic or hydrologic data projection such as precipitation, temperature and river flow. Consequently, the proposed method along with the modeling workflow could play an essential role in informing adaptive water management and governance decisions such as water rights allocation, the prioritization of critical sectors (e.g., municipal/residential, agricultural) whenever the available resource (supply) is inferior to the demand.

We want to point out that our literature review was not intended to be an exhaustive assessment of future water estimation methods for each of the targeted economic sectors. Moreover, given the criteria for selecting the references, such as the time frame considered (1990–2024), our review could not be exhaustive. However, we did ensure that we covered the universe of methods for future water demand estimation by two complementary search approaches: a systematic approach and a snowball approach. This exercise enabled us to list a range of methods and approaches, from the simplest (e.g., linear regression) to hybrid approaches featuring second-generation scenarios (RCP, SRES, SSP, SPA) integrating quantitative and qualitative data through narrative frameworks. Despite this nonexhaustive evaluation, the references identified enabled us to respond adequately to our two research questions. Beyond the limitations relating to the exhaustiveness of the study, our review could have presented statistics concerning, for example, the temporal distribution of the references consulted. This was not possible because of what we would call a partial contamination of the temporal information, either at the level of the bibliographic databases (improper indexing) or when formatting the attributes of the searched references (years of publication, authors) for export. The problem could also arise at the level of the references processing tool, Rayyan (Johnson and Phillips, Reference Johnson and Phillips2018), during the references importation step.

Conclusion

This literature review contributes a fairly comprehensive account of the body of knowledge accumulated on future water demand estimation methods. It represents the cornerstone for the development of a modern method for short to long term water demand estimation that: (a) considers the specific features of the main national economic sectors as well as the influence of environmental and socioeconomic factors and (b) is capable of being applied to several nested geospatial scales from the municipal scale to the national scale.

The paper proposes a streamlined methodological approach that adheres to the standards of state-of-the-art literature reviews. For instance, we applied the emerging framework named STAR in conjunction with the standard PRISMA framework to support, respectively, the implementation of reference search strategies as well as the formulation of research questions and the screening of retrieved references from selected bibliographic databases. Our analysis of the data extracted (e.g., factors, variables, methods/models/approaches, spatiotemporal scale) from the references allowed us to introduce a new parsimony indicator for existing water demand estimation methods, as well as new nomenclature for the classification of quantitative and qualitative scenario-based approaches. The analysis also revealed that a hybrid method featuring three emerging approaches, computational intelligence, SD, and probabilistic scenarios, would be the most appropriate for integrated modeling of linear and nonlinear relationships between variables in the various factors and economic sectors of interest over the long term. To support the implementation of such a method, we propose a comprehensive workflow based on the Python programming language and some key libraries such as the PySD, Django and GeoDjango. The purpose is to support the complete execution of spatial SD models, especially within a nexus modeling approach context, using a Python development environment, thus without the use of commercial software systems.

As future directions go, we plan to assess the complexity of the method through the simulation of future water demand of two critical economic sectors: agricultural and municipal of a pilot watershed, that of the Nicolet River, in Quebec. This case study will adopt the proposed probabilistic scenario-based approach where scenarios are co-created with water stakeholders of the pilot watershed. Additional sectors can be added after this initial evaluation effort. Putting the method into practice in an incremental or agile manner should provide useful feedback on its robustness and relevance for integrated water demand planning. The specific features of the proposed method and associated workflow will be presented in concrete terms through an assessment at the two spatial scales, that is, municipality and watershed.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2025.10009.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/wat.2025.10009.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Louis R. E. Asie and Louiné Célicourt, currently graduate students at the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (QC, Canada), for their contributions to the paper, particularly for the initial design of, respectively, Figure 2 and Figure 3 used herein.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: A.T.S., H.J.C., and P.C.; methodology: A.T.S., H.J.C., and P.C.; data curation: A.T.S. and H.J.C.; writing – original draft: A.T.S., H.J.C., and P.C.; writing – review and editing: M.J.L, A.N.R, S.J.G., and P.K.; project administration, funding acquisition, methodology, conceptualization, supervision: P.C.; all authors approved the final submitted draft.

Financial support

This research was supported by grants from the Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Lutte contre les Changements Climatiques, de la Faune et des Parcs (MELCCFP) of the province of Quebec and Ouranos (project #711900).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

The research meets all ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the study country.

Comments

No accompanying comment.