Scholars have long debated how the economic opportunities and costs of globalization impact the politics of taxation and redistribution.Footnote 1 These works generally show that globalization puts expansionary pressure on the welfare state, driven in large part by growing support for taxation and redistribution. Trade, investment, and immigration both displace workers—creating demands for compensation—and expose people to volatile international markets.Footnote 2 Largely missing from this debate, however, is a key group of winners from globalization: migrants and their families. While migration is known to alter the character of host-country politics,Footnote 3 its impact on the political preferences of migrants and their broader sending communities remains relatively unexplored.Footnote 4

Nearly 300 million people currently live overseas (that is, out of their home country), and many more have returned home after living overseas.Footnote 5 These migrants can be important agents of political and economic change in both host and home countries. Immigrants represent an important voting bloc in many high-income democracies, including the United States, with nativist politicians frequently warning of immigrants’ supposed preferences for greater public services.Footnote 6 Members of global diaspora communities send home financial as well as political remittances in the form of campaign contributions, political knowledge and advocacy, and other forms of formal and informal participation. Former migrants, meanwhile, frequently become local community and political leaders after returning home with improved economic resources and new experiences.Footnote 7

Does migration lead migrants to become more or less supportive of taxation and redistribution? Globalization research has focused on two mechanisms that increase support for the welfare state: economic displacement and exposure to market volatility. However, these mechanisms may not apply to migrants. Unlike displaced workers, migrants typically gain economically from working abroad. Moreover, families often use migration strategically to reduce economic risk that comes from domestic economic conditions. This suggests migrants might actually oppose redistribution—a possibility overlooked by current theories that focus on globalization’s losers. Examining how migration affects the political preferences of migrants and their families can therefore help us develop more nuanced understandings of how globalization impacts the politics of taxation and redistribution.

We argue that migration decreases migrants’ support for the welfare state. Personal economic advancement is one of the primary drivers of migration,Footnote 8 and migrants stand to make significantly higher wages in host societies than in their home countries.Footnote 9 It is well established that pecuniary gains lead people to embrace more fiscally conservative policies.Footnote 10 At the same time, the process by which economic gains are achieved, we argue, is just as important as the gains themselves. Migrants self-select into migration and work hard to navigate foreign cultures and markets. Through this process, they attribute success to their own hard work, build self-confidence, and learn to rely on themselves rather than the state.Footnote 11 The process of cultivating economic autonomy through self-reliance leads migrants to anticipate that migration will be a stepping stone toward greater well-being and upward mobility.Footnote 12 By contrast, while migrants’ left-behind families typically benefit economically from remittances, they do not have the same experience of earning income through personal hard work and risk-taking. Therefore, while migrants would be predicted to adopt more fiscally conservative attitudes, household members would not.

Studying the effects of migration on political attitudes is methodologically challenging. People who are interested and successful in moving abroad are almost certainly systematically different from those who are not, confounding comparisons across groups. Without altering the legal frameworks that structure cross-border migration, efforts to promote international migration and analyze its effects have largely proven unsuccessful.Footnote 13 A central challenge in facilitating overseas migration has been identifying people who want to migrate but cannot.

Our research design, geographical setting, and sample selection process allow us to overcome these hurdles. We conducted a randomized controlled trial in which potential migrants in India were connected with hospitality-sector jobs in the Middle East. The sending region in our study is the Northeast Indian state of Mizoram. Because Mizoram has traditionally been isolated from outside labor markets, international migration opportunities were both novel and potentially lucrative for residents, whose domestic employment prospects are limited. Working with local governmental and nongovernmental agencies, as well as with training and recruitment firms, we identified individuals interested in overseas employment and randomly selected half of them for a training and placement program for employment in carefully vetted hospitality-sector jobs in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Our subjects joined the millions of labor migrants working in the Global South and in the Gulf in particular; the India–United Arab Emirates (UAE) migration corridor is the second-largest in the world, after the Mexico–United States corridor.Footnote 14

Program participants and their household members were surveyed approximately two and a half years after treatment selection—two years after the treatment group began to migrate overseas. To obtain a fuller picture of how migration affects migrants, we also surveyed the subjects at baseline (prior to selection) and at midline (after treatment selection but before migration). We also conducted long-form interviews with migrants and with matched individuals in the control group.

Our findings shed light on the channels by which international mobility affects political attitudes, earnings, and household decision making. In the first stage, our intervention was highly effective in enabling enterprising, educated Indians to move overseas. Twenty-three percent of individuals in the treatment group migrated overseas for work, while only 3 percent of those in the control group did. Although program participants across the board preferred overseas opportunities to domestic ones, only those in the treatment group were able to substitute the former for the latter.

Most importantly, we find that migration significantly reduced migrants’ support for the welfare state. At endline, our preregistered index of fiscally conservative attitudes was 0.35 standard deviations higher in the treatment group than in the control group. Treatment-group individuals were less likely to support taxation and redistribution, less likely to support state intervention to reduce inequality, and more likely to say that economic success is a result of personal effort rather than circumstance. Yet migrants’ household members became more supportive of taxation and redistribution.

These results—migrants becoming more fiscally conservative but household members not—appear to be driven not only by material gains but also by the process by which those gains are achieved. First, both migrants and their households experienced substantial economic gains from migration. Two years after the program began, people in the treatment group were earning more than twice as much per month as those in the control group, notwithstanding similar rates of employment. These material benefits were felt by family members as well; the left-behind families of individuals selected for treatment reported substantially higher household incomes, assets, and remittance-sending. Thus, material gains alone do not appear to explain the difference in redistribution attitudes between migrants and their family members.

Second, migrants became more financially independent, self-reliant, and confident in their future economic prospects. Treatment-group individuals expressed significantly more optimism regarding their futures and more willingness to prioritize their careers over marriage and childbearing. Third, people selected for the program became markedly more opposed to taxation and redistribution as they were preparing to move overseas. This illustrates how the prospect of future upward mobility and the effort migrants put into moving overseas can instill confidence, self-reliance, and a commitment to principles of economic autonomy. Last, long-form qualitative interviews highlight the mechanisms by which migrants’ economic confidence and financial independence following migration shifted their political preferences. Together, the evidence suggests that the source of economic gains matters: income earned through personal effort reduces support for redistribution, while passively received remittances have no such effect.

We find no evidence for several alternative explanations. Interacting with high-capacity, low-taxation regimes did not decrease migrants’ trust in Indian institutions, thereby reducing support for redistribution. Nor is there evidence that the training program itself—the first component of our intervention—shifted redistribution attitudes or economic outlooks. Also, COVID-19 shutdowns did not have different effects on the treatment and control groups.

Our findings contribute to two key debates in the political economy scholarship. First, they demonstrate how migration reshapes support for the welfare state among migrants themselves, not just native-born communities. Like other manifestations of globalization, cross-border migration influences both demands on, and attitudes toward, the welfare state. We find that migrants, like the native-born, largely turn away from taxation and redistribution—but because of what they stand to gain rather than what they stand to lose.Footnote 15 Second, our findings help explicate the mechanisms by which economic gains shift views on redistribution: fiscal attitudes depend not just on the income that people earn, but also on how they earn it.

Theory of Migrants’ Welfare State Preferences

How does the act of migrating abroad impact individuals’ preferences for redistribution? Migration is one of the main avenues for upward mobility in the global economy, making migrants main economic winners from globalization.Footnote 16 Examining migrants’ political economy preferences is important for two reasons. First, migrants and their families are a large and growing constituency the world over.Footnote 17 Importantly, they often maintain political ties to both their home and host countries, potentially influencing policy outcomes in both locations. Understanding migrants’ views can help reconcile competing findings. For example, migrants in the West largely support leftist, pro-immigration political parties,Footnote 18 but diasporas are an important support base for some fiscally conservative parties in their origin countries, such as the Bharatiya Janata Party in India, the Justice and Development Party in Turkey, and the Liberal Party in Brazil.Footnote 19 Second, studying how migration changes redistributive preferences can help us better understand how economic resources, opportunities, and financial independence—particularly when they originate from globalization—broadly shape political attitudes. Thus, for both empirical and theoretical reasons, migrants’ welfare-state attitudes are important for elucidating the politics of globalization.

How Migration Affects Migrants’ Political Attitudes

To theorize the determinants of migrants’ welfare-state preferences, we turn to the international trade literature, which suggests that globalization has two distinct economic impacts on voters: economic gains and losses; and increased income volatility. Canonical work argues that economic volatility increases demand for the welfare state.Footnote 20 As Rodrik argues, “government spending appears to provide social insurance in economies subject to external shocks,” with welfare expenditure serving as a “risk-reducing instrument” for globalizing economies.Footnote 21

Importantly, attitudes about taxation and redistribution reflect a combination of personal pocketbook concerns and broader normative attitudes. Individuals may weigh the potential impacts of specific state-sponsored welfare programs and likely costs in taxes on their own material welfare. At the same time, they hold broader attitudes on the appropriate roles of state action versus personal responsibility in addressing inequality.Footnote 22 These broader normative attitudes can influence a wide variety of social and political views. For example, in India, attitudes toward the welfare state drive conflicts over how state resources and opportunities are allocated across regions and identity groups.Footnote 23

How does this argument apply to cross-border migrants? On the one hand, we may expect that migrants also become more supportive of redistribution because of the significant volatility associated with migration. For example, migrants are subject to sudden changes in host and home countries’ economic and immigration policies, which may make it difficult for migrants to access jobs, send remittances, stay in the host country, or return home. The effects of volatility can vary with migration type; circular migrants, for example, may face more volatility because they are affected by policy changes in both countries. Because migrants face greater volatility than non-migrants, we may expect them to demand greater state involvement and redistribution. Native-born citizens and anti-immigration political parties often warn that immigration will have this effect, increasing demands on the welfare state.Footnote 24 For this reason, immigration generally leads to less support for the welfare state among native-born populations.Footnote 25

In contrast, we argue that there are important reasons that volatility does not affect migrants in the same way it affects workers in importing and exporting sectors. To start, migration is inherently an individual decision. Workers in tradable sectors likely view the state as responsible for compensating the risks and volatility that emerge from globalization because it is the government’s tariff policies that influence where factories are opened and closed. But migrants themselves choose to move, live, and work abroad. Therefore, migrants should be less likely to view government policy as responsible for their economic experiences or prospects, compared to other economic-policy domains. Migrants also take on risks that typically accrue individualized economic returns that dwarf the impacts of reducing restrictions on cross-border flows of goods and capital.Footnote 26 Therefore, potential economic gains from migration should outweigh downside risks as a motivating factor, especially for people who self-select into those risks.

Our core argument is that migration reduces migrants’ demands for taxation and redistribution for two reasons. First, we expect that the significant individualized economic gains that accompany migration are a key driver of migrants’ preferences for a shrinking welfare state. Second, we expect that how migrants accrue income and wealth—through grit, hard work, and sacrifice—fosters a commitment to principles of economic autonomy and, in turn, opposition to state-led taxation and redistribution.

Economic Gain

We expect migrants’ views on redistribution to shift because of the material gains they accrue from migration. Many people in low- and middle-income countries migrate because they see it as a path toward economic gain.Footnote 27 Because wage differentials are starker across national boundaries than internally,Footnote 28 migrants anticipate greater economic gains internationally than domestically.Footnote 29

This is especially true for people whose domestic employment choices are constrained for structural reasons. Members of marginalized ethnic groups, for example, may face systemic barriers to economic advancement in local labor markets.Footnote 30 They encounter discrimination in hiring and promotion, lack access to kinship-based professional networks, and frequently face wage differentials in identical jobs performed by members of majority groups.Footnote 31 Overseas employers are less likely to discriminate in hiring and promotion based on the social hierarchies in migrant-origin regions, making international employment especially attractive for members of these groups.Footnote 32

Yet cross-border migration opportunities are out of reach for the vast majority of people in the developing world. In many destination countries, stringent immigration policies pose insurmountable barriers to those seeking entry for employment. And even when immigration is easier, most potential migrants lack critical knowledge and resources: information on jobs; connections to viable employers; occupational skills and industry “know-how” to demonstrate suitability for specific jobs; interviewing experience; and assistance in navigating the complex bureaucratic hurdles to migration.Footnote 33 In such contexts, recruitment and placement agencies serve as critical “migration institutions,”Footnote 34 closing these gaps and providing access to overseas employers. Connecting individuals with these institutions, therefore, should enable job-seekers to migrate overseas for work.

In turn, people who overcome barriers to migration face a new landscape of economic possibilities. Standard factor proportion models hold that migrants should receive real income gains from moving from relatively labor-abundant to relatively labor-scarce societies.Footnote 35 Some observational studies support this contention, showing that migrants fare better economically compared to non-migrants in their home country.Footnote 36 And because of migrant remittances sent back home, their families’ incomes and assets often increase as well.Footnote 37

Yet, experimental evaluations of international migration’s effects on the economic well-being of migrants and their families are rare,Footnote 38 and isolating this effect presents significant inferential challenges.Footnote 39 Migrants differ systematically from those who do not move; migrants might be more entrepreneurial, have access to better professional networks, or have more household assets and education. In fact, other scholars have argued that the up-front costs of migration outweigh the long-run benefits, especially for low-skilled individuals from poorer countries.Footnote 40 This suggests that migration has positive economic effects, but that evidence is needed as to whether these benefits outweigh the costs.Footnote 41 Typically, higher-paying jobs abroad provide an opportunity for migrants to improve their wages and send remittances to household members at home.Footnote 42

We argue that by bolstering their economic resources, migration reorders individuals’ political preferences, particularly regarding the size of the welfare state. Observational and experimental studies show that people who experience economic gains become less supportive of taxation and redistribution.Footnote 43 This effect could be purely the result of self-interested, material considerations: people are eager to protect their newfound gains from taxation, and their increased wealth reduces their dependence on government assistance. But these same studies also suggest that economic gains drive shifts in the ideologies that undergird support for taxation and redistribution. People who experience economic gains become more likely to say that economic advancement is possible without government assistance, that people are responsible for their own economic destinies, and that those who gain economically are therefore deserving of their gains. Given that migrants stand to earn higher salaries overseas, we should expect migrants to become significantly less supportive of taxation and redistribution and less likely to believe that it is necessary or deserved.

Self-Reliance

We argue that migration also changes migrants’ attitudes for psychological reasons, by shaping their perceptions of their economic pasts and futures. In particular, migration encourages migrants to become more self-reliant—that is, more likely to believe themselves capable of achieving economic goals without assistance. The process of migration requires significant effort and risk-taking, even compared to other forms of employment-related upward mobility. To gain economically, migrants make fraught decisions to leave their homelands, navigate immigration policies, and adjust to living and working in foreign environments. Even migrants who return to their sending regions typically do so with skills and experiences that they could not have gained at home.

Therefore, migration should shape views on both past and future economic gains, and therefore also views on state taxation and spending. First, migrants are likely to become more confident in their own ability to overcome economic and social challenges and less likely to believe they will need state intervention in the future. Bazzi, Fiszbein, and Gebresilasse call this “rugged individualism,” and show that the harsh challenges that migrants on the American frontier had to navigate led to more individualistic attitudes and, consequently, more skepticism of welfare policies.Footnote 44

Second, the skills and opportunities provided by migration promise continued material advancement in the future. Prior work shows that individuals are aware of the prospect of upward mobility and that they may shift their economic decisions and political preferences based on anticipated gains.Footnote 45 Migrants who successfully navigate the challenges involved in relocating overseas are plausibly much more confident of their economic futures—both because they have demonstrated their own resourcefulness and because the prospect of upward mobility may amplify their belief in that resourcefulness. For this reason, migrants are less likely to perceive themselves as likely to need government-provided insurance.

Third, migrants’ experiences foster a broader belief that personal effort leads to economic success and that economic gains are therefore deserved. As migrants overcome challenges independently, they are likely to develop this belief. Research shows that when their hard work is rewarded with success, people are more likely to attribute economic outcomes to personal effort rather than government policy or luck.Footnote 46 Migrants, thus, may view their achievements as justly earned. A large body of work has demonstrated that such beliefs in the link between effort and success are associated with lower support for state-led redistribution.Footnote 47

Overall, we expect that the combination of economic prospects and the experience of accruing wealth through personal grit will lead migrants to believe that personal effort drives success, making them more opposed to taxation and redistribution and less supportive of state intervention to reduce inequality. This combination of economic gain with a perception of deserved upward mobility recalls the findings of Liu that Chinese adults who graduated from college after public service reform expanded merit-based government employment were less supportive of redistribution than those who graduated before.Footnote 48

Distinguishing economic gain from self-reliance effects. We argue that it is not only economic gains but also the manner in which they are earned that shapes individuals’ redistribution preferences. This theory leads us to predict different effects for migrants and their household members. Household members also stand to earn considerable economic dividends through remittances. However, they lack the experience of earning their income through self-reliance and hard work; to the contrary, they become more dependent on others for their economic security. We therefore predict that migrants’ household members will not become more supportive of fiscally conservative policies. Together, this implies that migration’s impact on welfare-state preferences depends not only on individuals’ economic standing but also on their confidence, self-reliance, and perceptions of how they earned the new income. In other words, the impact of migration on redistribution preferences will depend on the pathways by which it generates economic opportunity. (Conversely, if economic resources alone drive preferences for redistribution, we would expect that both migrants and their household members become less supportive of redistribution.)

Alternative Arguments

There are alternative explanations for potential changes in migrants’ political economy preferences. The most notable of these is that migrants experience new economic and political institutions overseas and compare them to their home countries’ institutions, which shapes their views of government and economic policies.Footnote 49 These mechanisms are likely to be specific to the institutional and economic contexts in the home and destination countries at the time of migration. Regardless of the context, redistribution views are likely to be closely related to trust in government institutions. For example, Indian migrants residing in Gulf countries might observe the high capacity of governments there running on relatively low tax rates and become less trusting of the Indian government or less supportive of high taxes. Likewise, India–Gulf migrants in 2020–2021 were plausibly quite impressed with Gulf governments’ effective handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, especially in contrast to the Indian government’s response, which might have reduced their trust in the Indian government and high taxes. Government programs that facilitate migration may also increase migrants’ trust in home-country governments and increase support for state-led redistribution. In our empirical design, we pursue strategies to test these alternative mechanisms.

Why Study Migration Within the Global South?

Why look at the politics of migration through the lens of South–South migrants—and particularly of migrants and sending communities? More than 40 percent of migrants worldwide, nearly 120 million, live in the Global South.Footnote 50 About one in six international migrants live in the Gulf region alone, most of whom come from South and Southeast Asia.Footnote 51 The vast majority of migrants in the Global South, as in most other regions (notably excluding the United States), migrate to seek out job opportunities and often return home after employment stints abroad. In all, there are nearly 80 million labor migrants in the Global South and millions more who migrated for family reasons.Footnote 52

Scholarly work on migration, however, has focused disproportionately on the politics of receiving communities in the Global North (see Appendix G.4). Studying South–South migration flows is important because such migrants play critical roles in the economic and political life of sending countries. First, they have an influence through their families. The resources and ideas they send home can influence political behavior. For lower- and middle-income countries in the Global South, out-migration is one of the primary ways that globalization shapes the domestic economy. Because wage differentials are starker across national boundaries than internally,Footnote 53 migrants stand to gain considerably from overseas employment and send much of those gains back to their communities. Worldwide, financial remittances represent a greater source of international income than foreign direct investment.Footnote 54 Migrants can also influence the politics of their home communities through “social and political remittances”: they experience different political and economic systems and communicate their experiences back to friends and family. Migrants are often noted as a source of social and political change.Footnote 55

Second, South–South migrants are more likely than South–North migrants to return home after periods of migration overseas. The most common destination countries in the Global South, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, typically have very restrictive paths to permanent residence or citizenship. Economic migrants within the Global South typically return home after short stints of employment abroad.Footnote 56 This means that they can play an outsized role in their home communities, earning higher salaries overseas and returning to their communities with greater economic resources. For both of these reasons, studying how migration shapes the political attitudes of migrants and their families, especially those regarding the economy, is important to tease out the effects of migration in the developing world.

Research Design

Setting

Our study focuses on hospitality-sector employment opportunities in the GCC states for young people from Mizoram.Footnote 57 Mizoram is a small, geographically isolated border region that is home to the Mizos, an ethnic group classified by the Indian government as a Scheduled Tribe in view of its historical marginalization. Like other such groups in India, Mizos face poor economic conditions and substantial barriers in domestic labor markets. In Mizoram, private-sector employment is anemic, and government employment is highly politicized. Meanwhile, even educated English-speaking Mizos have difficulty finding work in mainland India, where they face discrimination as conspicuous racial and religious minorities.Footnote 58 Mizos are phenotypically closer to Southeast Asian than South Asian population groups, and the vast majority are Christians.

GCC employment opportunities, meanwhile, fuel a large and growing migration corridor from South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa to the Middle East. More than 40 percent of the world’s migrant population comes from Asia, and more than 60 percent of these people emigrate to other Asian and Middle Eastern countries.Footnote 59 India is the world’s largest source of emigrants (18 million worldwide) and recipient of remittances (USD 110 billion per year); migrants from South Asia account for nearly 50 percent of some GCC-country populations.Footnote 60

The GCC countries have a sizable demand for foreign English-speaking workers to serve in the hospitality sector. Labor migrants earn far higher wages in the GCC than in similar work at home, and remittances from temporary workers frequently serve as fuel for growth and investment for migrant-sending communities. Other regions of South Asia, such as Kerala, Bangladesh, and Nepal, have leveraged labor migration and remittances into substantial economic growth.Footnote 61 Because of Mizoram’s remoteness and small population, the state has had few connections to employers abroad and little emigration. Following the example of these other regions, the Mizoram state government and local NGOs decided to encourage workers to seek employment opportunities abroad, and sought assistance to evaluate a program to place Mizos in hospitality-sector jobs in the Gulf region. For more on our study setting, see Appendix A.1.

Recruitment Strategy and Sample

We identified and recruited a group of prospective candidates interested in migrating to GCC countries for employment but lacking the know-how and connections to do so. We relied on a variety of media to advertise the opportunity. We placed advertisements in leading Mizo newspapers and television networks, distributed recruitment materials with the help of local NGOs (most notably Mizo Zirlai Pawl, Mizoram’s largest community organization), and attended government-sponsored job fairs. Materials were translated into Mizo to reach a wide audience. The advertisement period was two months in summer 2018. While we targeted the entire state of Mizoram, most applicants came from Aizawl, which was unsurprising given the higher educational attainment and English skills in the capital. All our advertising materials asked applicants to be eighteen or older and have at least Grade 10 standard education. We also screened them for English competency.

Before treatment assignment, all subjects were surveyed at baseline by a Delhi-based survey firm (CVoter) to record basic demographics and pretreatment measures of our key outcomes. (Appendix A.3 discusses our survey methodology.)

The resulting pool of 392 candidates is broadly reflective of the upwardly mobile population that stands to benefit from work abroad: young, educated, and unemployed (Table 1). Their average age was twenty-three. More than 70 percent had completed Grade 12, and more than 85 percent were unemployed. These characteristics are similar to those of South Asian migrants in the UAE and other Gulf countries more broadly (Appendix G.1 compares our sample to Gulf migrants from other parts of India). From this pool, half (196) were randomly selected to attend a training and recruitment module. Before selecting subjects into treatment and control, we used a matching algorithm to generate blocked pairs to ensure balance along key covariates which might predict economic prospects: age, gender, education, and English proficiency (as judged in our own screening).Footnote 62 We then randomized between each pair, assigning one to treatment and the other to control. Our randomizations resulted in observably similar groups of respondents distributed between the two conditions (see Appendix B.1 for balance tables).

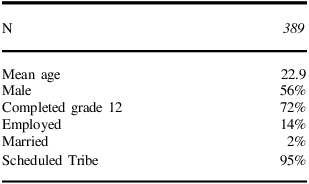

Table 1. Demographics of subjects

Note: Due to an administrative error in matching registrations to surveys, we are missing baseline demographic data on 3 of the 392 candidates.

Treatment: Job Training and Recruitment

The main treatment in this study has two parts, designed specifically to connect subjects with potentially lucrative employment opportunities in the GCC.

First, all selected individuals were eligible for a free, five-week hospitality training program (from October through November 2018) administered by a Bangalore-based job-training firm (Free Climb) and hosted by a local NGO (Social Justice and Development India) in conjunction with the government of Mizoram’s Youth Commission. This program had two parts. The first, classroom-based part (three weeks, full-time), included instruction and role playing on basic food preparation, counter service, casual dining service, and housekeeping. During the second part (two weeks, part time), managers of local hotels and restaurants showed participants how their establishments function. Concurrently, instructors helped participants prepare résumés for foreign employers and practice interview skills, while also providing basic information on regulations and resources in the Gulf region. This training was intended to offer only a basic understanding of the industry to help candidates credibly interview for positions with employers abroad; employers in GCC regions provide extensive job-specific training once employees are hired.

In the second component of the intervention, individuals in the treatment group were invited for interviews with employers in the hospitality sector in the GCC. Our recruitment partner, Mumbai-based Vira International, selected (and vetted for ethical labor practices) businesses interested in recruiting and sponsoring workers from Mizoram. These ranged from multinational food and beverage service outlets such as Pizza Hut and Costa Coffee to luxury hotel firms such as Mandarin Oriental. These potential employers conducted several rounds of remote and in-person interviews between March and July 2019. Every individual in the treatment group was invited for interviews, typically more than one, and employers offered jobs to most of those who attended interviews. On the offer of employment, the employers applied for visas on behalf of the job candidates. Those with job offers received logistical assistance in obtaining immigration documents and medical certificates, requirements for employment in the GCC. The recruitment firm and our local project manager scheduled meetings and checked paperwork for the candidates. More details on our intervention are provided in Appendix A.4.

The treatment bundles two elements: the training program and opportunity for overseas placement. This bundling was both theoretically motivated and practically necessary. First, migration requires both information on overseas opportunities and logistical infrastructure. Our treatment was designed to make the migration process in the context of a field experiment more realistic by providing information and connections similar to those that potential migrants would require under normal conditions. Second, foreign employers had little information on the labor market in Mizoram and wanted assurance from an outside training firm that candidates had the basic knowledge of hospitality-sector jobs. Nevertheless, an array of qualitative and quantitative evidence suggests that the placement opportunity itself, not the training program, explains any significant differences between the treatment and control groups. We investigate this evidence more fully in the Alternative Explanations section.

Ethical Considerations

Careful consideration was given to the ethics of this study, which was approved by institutional review boards at Columbia University, Stanford University, Dartmouth College, and the US Naval Postgraduate School. While international employment provides otherwise unattainable economic opportunities for many migrants, it also poses physical and psychological risks. Cases of migrant-worker exploitation in the GCC have been reported.Footnote 63 This study was embedded within the Research and Empirical Analysis of Labor Migration program, which aims to improve empirical knowledge regarding labor migration to the Gulf to promote fairer migration processes and better outcomes for migrants. The goal of our project was to evaluate a blueprint for ethical cross-border labor migration for governments’ and NGOs’ future use. We worked closely with partners to minimize the risks participants might face, to ensure that the benefits of the program flowed to the participants, and to protect participants’ informed consent.Footnote 64

We carefully vetted project partners; selected a sector (hospitality) that is relatively reputable (compared to construction, for example); screened employers for fair recruitment and labor practices; connected would-be migrants with agencies safeguarding migrants’ rights; and offered subjects extensive information on risks, rights, and resources. Appendix A.5 provides an extended discussion on ethics.

Outcomes and Estimation

The main endline survey was conducted in between January and March 2021, roughly two and a half years after the beginning of the program. Of the 392 pretreatment subjects, 248 (63 percent) responded to this survey. These surveys lasted around thirty to forty-five minutes and asked a variety of economic, social, and political questions. By contacting participants via WhatsApp as well as phone, the survey firm was able to reach those in India and those overseas. Following this survey, we conducted a similar survey of subjects’ family members—mostly parents, with a few older siblings—based on contact information collected from subjects on the baseline survey. This survey had a higher response rate, with 303 out of 392 responding (77 percent). A brief review of similar studies on migration and development programs in low- and middle-income countries (see Appendix B.5) shows that these response rates are fairly typical for studies attempting to recontact specific individuals in low- and middle-income countries.Footnote 65 Young job seekers frequently move or change their contact information, especially over the course of a two-and-a-half-year project.

A host of statistical tests indicate that attrition resulted in no systematic bias in the results among the main subjects (see Appendix B.2). First, based on multi-sample t-tests, there are no significant differences in response rates between the treatment and control groups. Second, there are no significant patterns in attrition based on pretreatment characteristics: OLS models predicting response rates based on these characteristics have no predictive value according to omnibus F-tests. Third, there is no evidence of any significant imbalance between the treatment and control groups before or after attrition. OLS models predicting treatment status by pretreatment covariates provide no predictive value in baseline, midline, or endline respondents, based on omnibus F-tests. Fourth, for the same reason, controlling for a variety of pretreatment covariates in OLS models has almost no effect on the main results. Last, a sensitivity analysis of the main results suggests that any bias in attrition would have to be very large to affect the main results. Together, these results indicate that differences-in-means between treatment and control respondents are likely to be valid estimates of the treatment effect among respondents, and possibly among non-respondents as well.

The equivalent tests for the secondary household-member survey reveal that the response rate for family members is significantly higher in the control group than in the treatment group, and there is some evidence of demographic imbalance between the two groups. We evaluated the potential bias resulting from these imbalances in two ways (Appendix B.2). First, we re-estimated the main results while controlling for all pretreatment covariates. We found that these imbalances bias slightly against our findings (that is, the effects would be larger if not for differential attrition). Second, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the approach of Lee to assess how widely the results may vary if we make different assumptions about differential attrition.Footnote 66 Even with extreme assumptions about differential attrition, our main findings would stand.

We evaluated migration and economic outcomes, alongside attitudinal and behavioral effects, associated with international job opportunities corresponding to the main preregistered hypotheses in our pre-analysis plans, asking two to six survey questions for each. We present all components individually (see Appendix C for question wording). Our main test of each hypothesis (according to our pre-analysis plan) measures the effect of the treatment on a single, z-score index combining all of the measures. Combining multiple measures into a single index holds two advantages. First, it reduces the number of comparisons, decreasing the risk of false positives. Second, it reduces statistical noise, increasing the power of our tests and decreasing the risk of false negatives.

We analyzed all data primarily with an intention-to-treat framework, testing the effect of treatment assignment (invitation to attend the placement program) on subjects’ attitudes. Appendix D reports the complier average causal effect estimates, which we preregistered as additional tests. For each primary outcome, we have a measure of the same outcome from the baseline survey. We therefore test these hypotheses with OLS, controlling for the baseline measure. We also report nearly identical results with simple difference-in-means comparisons (Appendix D). Due to the limited number of observations, small size of blocks, and the possibility of attrition, we did not include block (pair) fixed effects. Our figures show parametric confidence intervals, but our tables include p-values calculated with parametric standard errors and randomization inference—which yield nearly identical results. All hypotheses and procedures were preregistered on the Experiments in Governance and Politics online registry (20210608AE and 20190327AB). All of these hypotheses are evaluated either in this paper or in related papers.Footnote 67

Evaluating Mechanisms

Does migration alter political attitudes as a result of economic gains alone or also how those gains are realized? While migrants generally experience increases in income, self-reliance, and independence together, their family members accrue economic gains through remittances without having to work independently. We took two major steps to disentangle these processes and explain potential differences between the attitudes of migrants and their families. First, we conducted long-form, semi-structured interviews with members of the treatment group who moved abroad, as well as matched “likely migrants” in the control group in 2021, following our endline survey. The purpose of these interviews was to investigate possible causal processes in detail. The topics included motivations for moving abroad, experiences in a new country, comparisons between Mizoram and the host country, and subjects’ views on their economic circumstances and life plans.

Second, we conducted a midline survey of treatment and control subjects in January to March 2019, after selection to the training program but before anyone received job offers or moved abroad; 290 individuals (74 percent) responded to this survey. Comparing attitudes at this point helps us separate out economic gains (which came only later) from the psychological preparation and anticipation of financial independence that likely began beforehand.

Main Results

Overall, the endline survey produced strong evidence that opportunities to work overseas shape political preferences, economic conditions, and self-confidence. Treatment-group individuals were significantly more likely to move overseas for work, and they registered significant gains in personal and family income. They also became significantly more opposed to taxation and redistribution than control-group individuals. However, family members of treatment-group individuals did not experience the same effect—if anything, they became more supportive of taxation and redistribution despite significantly benefiting from remittances.

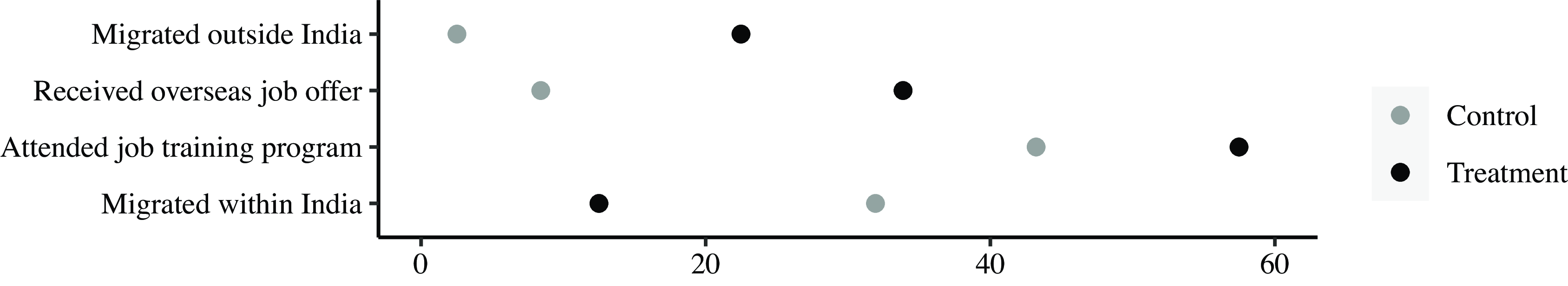

Migration

First, we find that the treatment had a large first-stage effect on subjects’ ability to migrate abroad, as Figure 1 documents. While 23 percent of the treatment group lived overseas at some point during the two years following the program, only 3 percent of the control group did (see also supplementary Table D.13). This effect is large relative to other field experiments on overseas migration. Beam, McKenzie, and Yang provide assistance and information about migration to potential migrants, but after intervention find that only 2.2 percent of the entire sample migrated, with the treatment having had no significant impact on migration rates.Footnote 68 A novelty of our research design is that we identified a sending region without an established history of out-migration and selected subjects at baseline who wished to emigrate abroad for employment. This allows us to isolate capacity to emigrate from desire to emigrate, and cleanly identify the impact of interventions that increase individuals’ ability to pursue employment overseas.

Figure 1. First-stage effects on migration

Notes: Percentage of treatment and control subjects with each outcome. All of these differences are statistically significant and in line with preregistered hypotheses.

The vast majority of the migrants moved to Kuwait or the UAE, with a handful moving to Qatar, Saudi Arabia, or Bahrain. About half of these migrants returned home at the end of their initial one-year contract, while half remained overseas, as some had accepted multi-year contracts with greater stability and status. These results are consistent with migration patterns between South Asia and the Gulf, where most labor migrants return home after one-to-five-year stints.

The endline survey illuminates how the program aided the migration process. Individuals in the treatment and control groups faced several hurdles in moving overseas, but the recruitment program seems to have lowered barriers at every step: subjects in the treatment group were more likely to apply for a job overseas, receive a job offer if they applied, receive a visa if they received an offer, and move overseas if they received a visa (supplemental Table D.14). Nearly all of those in the treatment group who moved abroad did so with the connections and help of our recruitment partner.

Strikingly, the treatment did not significantly increase the proportion of individuals who left Mizoram for work. While those in the treatment group were more likely to move overseas for work (23 versus 3 percent), those in the control group were more likely to move within India (32 versus 13 percent). In lieu of international placement opportunities, control-group subjects took domestic jobs elsewhere, particularly in the hospitality-sector hubs of Goa, Delhi, and Mumbai. Supplemental Figure D.5 temporally illustrates these trends, showing the proportions of each group that migrated domestically or overseas over the study period.

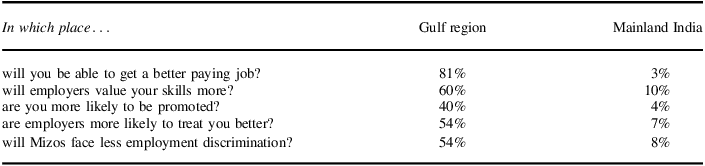

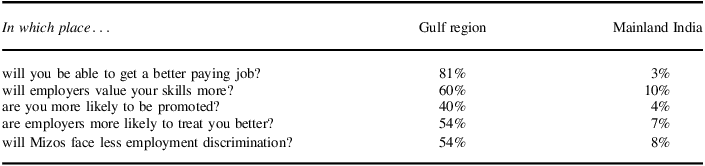

Why did so many of those in the treatment group choose to migrate overseas rather than stay in India? We argued that wage differentials are starker across national boundaries than internally.Footnote 69 Also, members of historically marginalized ethnic groups face systemic barriers to economic advancement in local labor marketsFootnote 70 and thus might find international employment opportunities especially appealing. Our results provide strong evidence for this hypothesis. Program participants viewed international employment as uniquely rewarding. In our midline survey, we asked them to rate their interest in job opportunities in the Gulf compared to other parts of India (Table 2). Respondents consistently reported that jobs in the GCC would pay more, provide more opportunities for promotions, feature better treatment by employers, and involve less ethnicity-based discrimination.

Table 2. Prospective migrants perceive international job opportunities as more valuable

Notes: Hypothesis was preregistered that Gulf jobs would be preferable to Mainland India jobs across all dimensions. Both treatment- and control-group subjects were polled. Remainder of responses were “don’t know/can’t say.”

Political Attitudes

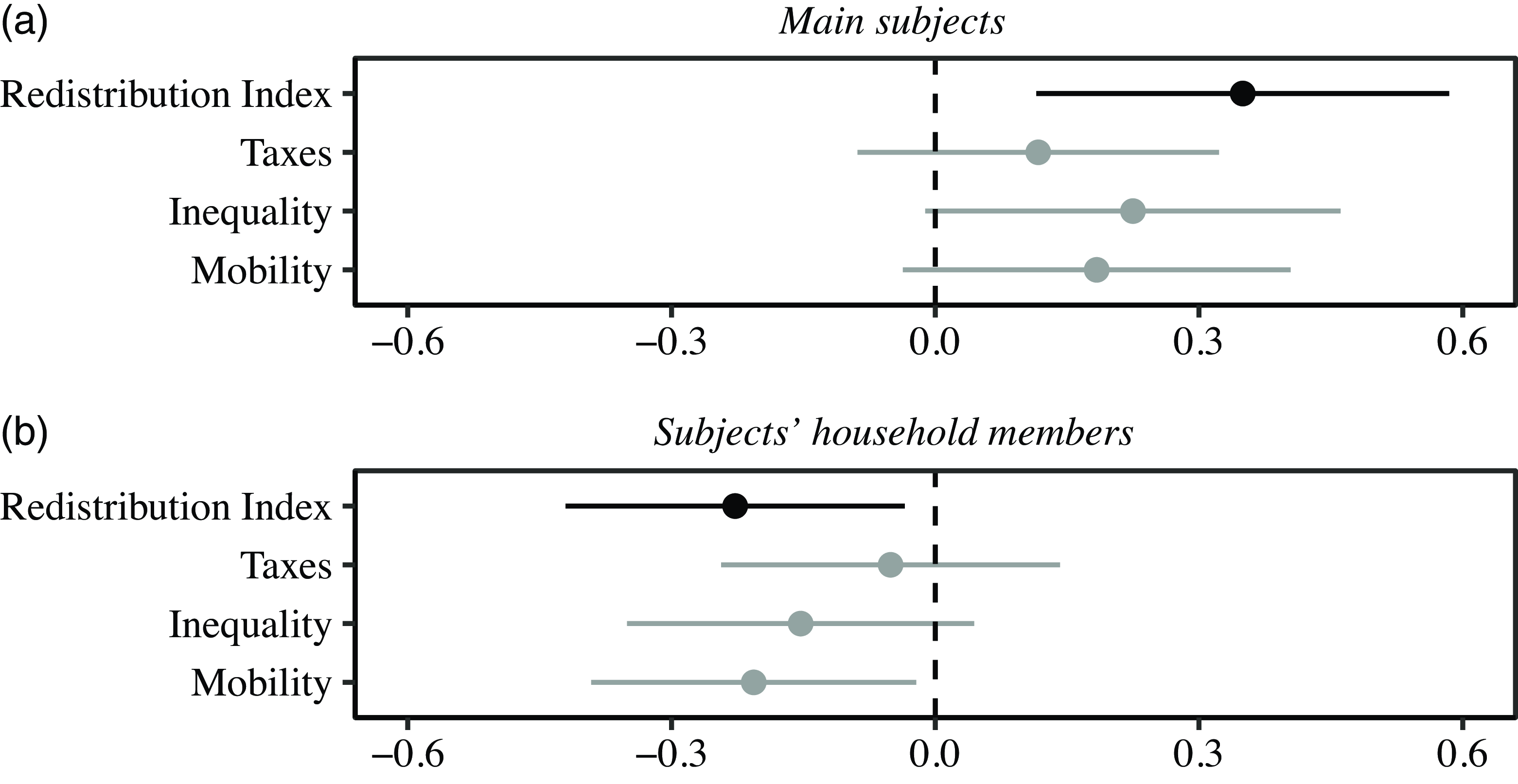

Consistent with our main argument, international employment opportunities significantly reduced migrants’ support for state-led taxation and redistribution. The top panel of Figure 2 shows the effect of overseas employment opportunities on three measures of support for state-led taxation and redistribution in their home country. At the endline, treatment-group individuals were more likely to strongly oppose high taxes for social spending in India (36 versus 30 percent) and more likely to disagree with the government’s intervening to reduce income inequality (16 versus 7 percent) than those in the control group. They also were more likely to agree with a sentiment that is known to underpin opposition to the welfare state: that it is “very possible” for the poor to advance economically with hard work alone (63 versus 50 percent).Footnote 71 When these measures are indexed together in our primary preregistered index, we find that access to overseas migration opportunities shifted the welfare-state attitudes of the treatment group by more than one-third of a standard deviation relative to the control group (see also supplemental Table D.15).

Figure 2. Treatment effects on redistribution attitudes

Notes: Treatment effects estimated by OLS, controlling for baseline measure of DV. Ninety percent confidence intervals shown, consistent with

![]() $p \lt .05$

on one-sided preregistered hypotheses. All effects are in standard deviations of DV, with positive sign indicating movement toward fiscally conservative positions. Taxes: Should the government lower taxes for ordinary people, even if that means it will have less funding for public services to help the poor in Mizoram? Inequality: Should the government reduce income differences between the rich and the poor? Mobility: In general, do you think it is possible for someone who is born poor to become rich by working hard?

$p \lt .05$

on one-sided preregistered hypotheses. All effects are in standard deviations of DV, with positive sign indicating movement toward fiscally conservative positions. Taxes: Should the government lower taxes for ordinary people, even if that means it will have less funding for public services to help the poor in Mizoram? Inequality: Should the government reduce income differences between the rich and the poor? Mobility: In general, do you think it is possible for someone who is born poor to become rich by working hard?

These estimated treatment effects are extremely large compared to other common determinants of taxation and redistribution attitudes. Within our data, treatment assignment was far more predictive of endline redistribution views than any pretreatment covariate: income, education, gender, and even pretreatment measures of redistribution. We also benchmarked our treatment effect against correlates of redistribution views using data from three major South Asian countries and the United States in the World Values Survey. The treatment effect in our survey (0.35 standard deviations) was larger than the effect of any comparable characteristic (education, gender, or union membership) on comparable redistribution questions in any of the four countries we examined (see Appendix D.3).

The effects are also quite large given the politics of taxation and redistribution in India. Our sample, like the Indian population, was extremely pro-redistribution. The result is also striking given that this program was co-sponsored by a state government office—treatment-group subjects could reasonably see themselves as beneficiaries of a government program.

What do these effects capture? One may interpret these results both as instrumental and as normative changes. Individuals in the sample are unlikely to pay significant taxes on their earnings—national and state income taxes are low in Mizoram and often nonexistent in the Gulf. Still, in both contexts they pay other forms of taxes, such as sales and business taxes. Hence, these effects may represent a broad concern about taxes on hard-earned salaries. More likely, however, they reflect a largely normative change: migrants turned against taxes and redistribution primarily because it felt unjust or unnecessary. Such normative changes tie closely into one of the axes of ideological conflict in India, statism—that is, the extent to which the state should dominate society and redistribute private property.Footnote 72 Indeed, our measures of redistributive preferences are closely linked to the state’s role in addressing poverty and inequality. Our findings, thus, indicate that migrants move closer to political parties and leaders less supportive of using the state to address economic issues in India. Migrants’ attitudinal shifts thus appear to be driven by changes in their broader political consciousness.

Turning to migrants’ family members, we find no evidence that migration decreased support for redistribution (bottom panel of Figure 2). To the contrary, parents and siblings of migrants became significantly more supportive of state-led welfare policies. Household members of treatment-group individuals were much more likely to strongly support government intervention to reduce income inequality than those of control-group individuals (73 versus 61 percent), and about as likely to support high taxes (23 versus 22 percent). They also showed evidence of an underlying attitude change, as they were less likely to believe it was “very possible” for the poor to advance economically with hard work alone (49 versus 56 percent).

These results have implications for long-standing debates on the impact of globalization on welfare policy. According to seminal studies,Footnote 73 globalization puts expansionary pressure on the welfare state as those who do not benefit from new economic opportunities demand more state support and as greater volatility in global markets motivates citizens to demand larger safety nets from governments. Yet recent work focusing on developing countries argues that globalization hollows out the welfare state.Footnote 74 Our micro-level evidence helps reconcile these contrasting claims. Migrants in our study, who benefit from overseas opportunities after becoming financially independent and self-sufficient, become less supportive of taxation and redistribution. In contrast, their household members, who gain economically from higher remittances but who become more reliant on those abroad for their incomes and thus develop less self-reliance in the global economy, acquire more pro-redistribution attitudes. This is evidence in favor of our theory: it is not economic opportunity alone, but its combination with beliefs about self-reliance and the prospect of upward mobility, that shapes welfare-state attitudes.

Mechanisms: Economic Gains Versus Self-Reliance

To demonstrate that it is not material gains alone that drive our results, but rather self-reliance coupled with upward social mobility, we provide evidence in two steps. All analyses in this section were preregistered (see the Research Design section). First, we compare the economic gains and welfare attitudes of migrants and their left-behind families. Second, we provide qualitative and experimental evidence from our study subjects to probe mechanisms.

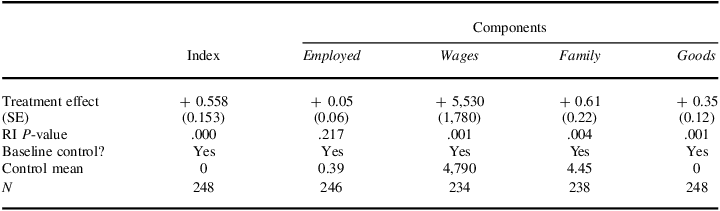

Shifts in Economic Standing

First and most importantly, both migrants and their families experienced significant economic benefits from overseas employment. As of the endline survey, individuals in the treatment group were on average earning more than twice as much as those in the control group (Table 3). The mean wage in the control group was approximately INR 4,800 (USD 65) per month, while the mean wage in the treatment group was over INR 10,400 (USD 140). This is particularly striking given that most of the subjects in both groups remained unemployed and that rates of employment in the treatment and control groups were not very different at endline (44 versus 39 percent). The wage increase was nearly entirely driven by the relatively small number of individuals in the treatment group (23 percent) who moved overseas for work. At endline, the mean monthly wage was INR 40,100 (about USD 540) for those currently employed overseas, INR 18,400 (USD 250) for those currently employed in Mainland India, and INR 12,800 (USD 170) for those currently employed in Mizoram.

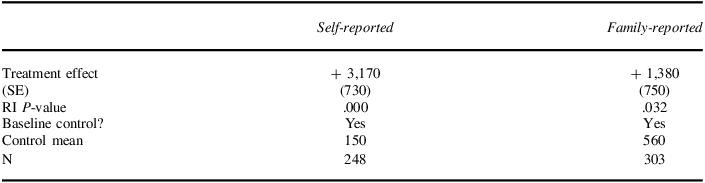

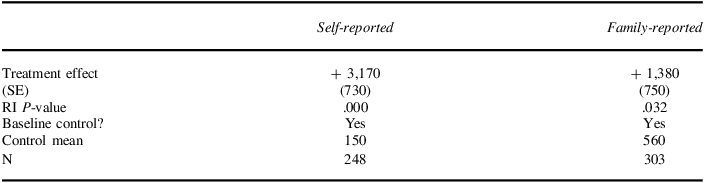

Table 3. Economic standing results

Notes: Treatment effects measured by OLS, controlling for baseline measure of DV. P-values are one-sided, per preregistered hypothesis. RI: randomization inference. Employed: employed at endline survey. Wages: personal monthly wages, in INR, rounded to INR 10. Family: family income on a 1–8 scale. Goods: standardized index of six household goods.

At the same time, migrants’ augmented wages significantly improved the economic standing of their families (supplemental Table D.17). On average, treatment-group individuals who moved overseas reported sending INR 14,000 (USD 200) per month, or about half of their wages, home to their families. Selection to the treatment group, therefore, had a significant and positive effect on self-reported remittances (Table 4). Likewise, the family members of migrants—and of the treatment group generally in the household survey—reported receiving significant boosts in remittances from overseas.

Table 4. Remittances results

Notes: Treatment effects measured by OLS, controlling for pretreatment income. Rounded to INR 10. P-values are one-sided, per preregistered hypothesis.

Consequently, assignment to the treatment group resulted in a substantial increase in their families’ overall economic circumstances, both in monetary terms and in lifestyle goods. Treatment-group subjects were half as likely to report a family income below INR 20,000 (18 versus 36 percent) and nearly twice as likely to report a family income above INR 50,000 (25 versus 16 percent). These differences also manifested in an index of household material goods. Treatment-group individuals were more likely to report their families as owning at least one computer (62 versus 53 percent), refrigerator (99 versus 95 percent), or motorbike (76 versus 68 percent).

Despite these large economic gains for both migrants and their families, as shown in the Main Results section, only the migrants became less supportive of increased taxation and redistribution. This implies that strong economic gains alone cannot explain the turn toward fiscally conservative attitudes.

Shifts in Self-Reliance

To examine whether increases in self-reliance drive our results on redistribution preferences, we perform a series of analyses. First, we draw from our long-form interviews with both treatment and control-group subjects and find that migrants were more likely to mention improvements in self-confidence and financial independence and to feel optimistic about their economic futures. We also provide three more pieces of suggestive evidence. Migrants were more likely to invest in their careers as opposed to having a family, indicating that they were more optimistic about their career prospects. They also report higher economic confidence. And they became less supportive of redistribution just before migration—that is, before realizing any economic gains, but after the prospect of upward mobility became apparent.

Qualitative evidence. We conducted in-depth qualitative interviews with migrants from the treatment group and with statistically matched non-migrants from the control group about their experiences as well as their political and economic attitudes. Our goal was to see whether migration shifted self-reliance, defined as the belief in one’s ability to achieve economic goals without assistance. To identify possible shifts in self-reliance, we looked for mentions of “confidence,” “security,” “stability,” “work,” “career,” “employment,” and “independence.”Footnote 75 From our analysis, three main themes emerge.

The first theme is that the overseas migrants had a stronger sense of financial security. Many reported being financially independent of their families: “I am able to earn and not rely on my family financially” (resp. 27); “I can now afford things for myself, and I don’t have to ask my parents for money anymore” (resp. 239). Others noted they could now meet their own expenses and still support loved ones back home: “I have a salary every month … I send money to my family and keep extra savings for myself” (resp. 40); “I am able to afford my own lifestyle and provide for my family” (resp. 88). Several migrants felt “more secure” than friends at home: “I think I am the most secure one among my friends financially” (resp. 228); “[I have] friends who have a college degree with no work, but I’m able to earn and support my family financially” (resp. 261). Thus migrants saw themselves as not only more financially independent but also more responsible with their earnings.

The second and more striking theme was that migrants expressed a great deal of pride in their economic success and attributed it primarily to their personal growth and confidence. One respondent said that they had become “more mature and confident,” and “more stable, and secure,” than their friends back home (resp. 179). Another remarked that he felt more confident than his friends at home, not only because of his higher earnings but because he was “able to work in a country where [he] knew no one and … adjust very well, and I think I have become more courageous and confident than them” (resp. 80). Another said that “after getting to work and experiencing many things, I think I am more confident than they are … There is more personal growth in myself” (resp. 44). These statements reflect migrants’ belief that their higher earnings were the result of their ability to succeed in new environments. In discussing these achievements, migrants also expressed a desire to safeguard their progress. One interviewee explained, “When it is our own money that we earn, we tend to spend it wisely and save up more than before” (resp. 44). Another appreciated the low taxation abroad, saying, “The government here does not take tax from the people, so I think that is good and better” (resp. 88). Such views reflect a belief in the power of hard work and a corresponding skepticism of redistribution, aligning with research that links success in unequal environments to stronger meritocratic beliefs.Footnote 76

The migrants also expressed optimism about their future ability to succeed independently. They said that they thought they had a “good chance because whatever job [they] apply for, the fact that [they] have work experience in a foreign country will put [them] at an advantage” (resp. 88). Or: “being able to work in a foreign country for my first job has given me high hopes that I have a bright career ahead” (resp. 44); “what I have learnt and experienced is a great asset to me and … I will be able to do well as long as I am hard working” (resp. 335). One said, “I think I am more mature than when I was in Mizoram, and I am more disciplined, and I have now the mindset to become better and do well and improve in the future” (resp. 40). In general, most migrants expressed a similar sentiment: because of their work experience and resilience in the Gulf, they would be in a better position to succeed in the future.

In contrast, control-group respondents described instability in their economic lives. Some had migrated within the country and returned, while others had stayed in Mizoram. A few reported not having any salaried work at all. One said that he had not been able to work “because of the pandemic and the road block by [neighboring] government [causing a] shortage of supply” (resp. 3). Despite his savings, he said, “I don’t think I am stable.” Another respondent noted that due to the pandemic she “had to spend without earning, so [she is not] secure right now” (resp. 16). Even those who returned from employment elsewhere in India reported a lack of financial stability due to lower salaries in Aizawl, Mizoram’s capital: “I don’t think I am secure, because I come from a poor family background and I am renting a flat here in Aizawl, so there are many things to spend money on, and it is difficult to have proper savings” (resp. 23). Together, these interviews show that our results were driven not only by the treatment group’s access to greater wages but also by their international migration fostering greater independence and economic confidence.

Shifts in confidence and life planning. Next, we provide evidence that migrants developed beliefs about being likely to make more money in the future, an indirect test of our self-reliance and prospect-of-upward-mobility channels. Access to migration overseas significantly improved migrants’ economic confidence and their willingness to further invest in their careers. Supplemental Table D.18 shows the effect of the treatment on an index of four measures of economic confidence. At the endline survey, individuals were modestly more likely to express confidence that they would be able to advance professionally, and that their next job would pay well. Overall, economic confidence among the treatment group was approximately 0.2 standard deviations higher than in the control group (

![]() $p \lt .10$

).

$p \lt .10$

).

We see stronger effects, moreover, on more durable measures of economic expectations: whether young adults are willing to delay marriage and childbearing plans to focus on their careers (Figure 3). Compared to the control group, treatment-group subjects expressed a significantly greater preference for delaying marriage and childbearing by the endline. Asked when they intend to marry and have children, those in the treatment group gave ages that were nearly two years older than those given by the control group (supplemental Table D.19). This treatment–control difference is larger than the difference between men and women’s preferences. To the extent that the welfare state alleviates the financial burden of family expansion and child-rearing, this shift in the household decisions of treatment-group subjects aligns with their diminished support for state-led taxation and redistribution. Overall, migrants’ greater economic confidence and decisions to invest more in their future careers provide suggestive evidence for the psychological mechanisms that underlie the change in political attitudes.

Figure 3. Ideal marriage and childbearing age

Notes: Marriage: At what age did you marry or do you plan to marry? Childbearing: At what age did you have children or do you plan to have children?.

Comparisons over Time

Finally, we demonstrate that treatment-group individuals’ economic and political attitudes began to shift even before they migrated and worked overseas (Figure 4 and supplemental Table D.15). This indicates that the prospect of future economic opportunities associated with migration shapes the treatment group’s redistribution attitudes. For this analysis, we conducted a midline survey in early 2019, after candidates had been selected for the overseas placement opportunity but before they accepted jobs or moved overseas. At this point, individuals in the treatment group had not yet gained materially from moving abroad, but they had already begun to anticipate future gains and view themselves as self-reliant.

Figure 4. Redistribution attitudes over time

Notes: Comparison of three-question redistribution index from Figure 2. One unit = 1 SD of index in control group

Treatment-group subjects increased in economic confidence relative to the control group by the midline. Even before they interviewed with foreign employers or were offered jobs, they saw their economic opportunities as significantly greater than those in the control group. They had also taken many challenging, concrete steps toward migrating overseas that were not included in the training program. Treatment-group subjects were more likely than those in the control group to have applied for a passport and sought out information on employers and labor laws abroad.Footnote 77 Any changes in political attitudes at the midline survey, therefore, are likely the result not of realized benefits but of effort and preparation to earn them, which shifted future economic prospects and attitudes toward opportunity and self-reliance.

Individuals in the treatment group experienced a significant shift in political preferences by the midline survey, becoming more fiscally conservative even before they saw any income gains from migration. At the midline, they were 0.21 standard deviations more anti-redistribution than the control group (Figure 4,

![]() $p \lt .05$

). At the endline, after some in the treatment group had received two years of high salaries overseas, these differences were qualitatively larger and more statistically significant (0.34 SD,

$p \lt .05$

). At the endline, after some in the treatment group had received two years of high salaries overseas, these differences were qualitatively larger and more statistically significant (0.34 SD,

![]() $p \lt .01$

). These results suggest not only that higher-income people are less apt to favor taxation and redistribution,Footnote

78

but also that perceiving oneself as more self-reliant and more upwardly mobile is sufficient to trigger similar attitudinal shifts.Footnote

79

$p \lt .01$

). These results suggest not only that higher-income people are less apt to favor taxation and redistribution,Footnote

78

but also that perceiving oneself as more self-reliant and more upwardly mobile is sufficient to trigger similar attitudinal shifts.Footnote

79

Together, the evidence on migrants’ increased feelings of independence and self-reliance, their bolstered economic confidence and lower willingness to invest in family planning, and their attitudinal shifts prior to registering economic gains offers strong support for our self-reliance mechanism. In contrast, we do not find evidence that economic gains alone consistently explain a shift in support for redistribution.

Alternative Explanations

We also see no evidence for three alternative explanations for the treatment effects.

Experiences and Trust in Government

One alternative causal story is that overseas migrants shift their views as a result of experiencing new economic and political institutions.Footnote 80 Indian migrants living in Gulf countries may become distrustful of the Indian government—and therefore the welfare state—after experiencing life under relatively high-capacity governments running on low tax rates (funded, instead, by oil production). But we do not find that people in the treatment group grew to distrust the Indian government. To the contrary, treatment individuals were significantly more likely than control individuals to say that their national, state, and local governments back in India were trustworthy and capable of solving problems (supplemental Table E.21). These results suggest that, if anything, migrants’ experiences overseas made them more trusting of the Indian government, which should have led to greater support for redistribution.

Training Program

A second possibility is that the job training program itself—not the opportunity to move overseas for work—shifted economic standing or political attitudes. We have significant reasons, both theoretical and empirical, to doubt this.

First, overseas job opportunities are extremely rare in Mizoram, while hospitality training programs are common. Local government organizations and NGOs regularly conduct free skills training programs as a way to reduce the region’s high unemployment rate. Of the individuals in the control group, 43 percent reported attending a job training program in the months following the baseline survey (compared to 58 percent of the treatment group). Candidates described these programs as extremely similar to our Mizoram-based training program. The job training conducted by our partners was very general, designed only to allow job candidates to credibly interview with overseas employers, who were unfamiliar with Mizoram’s local labor market. Migrants in our study described undergoing much more extensive company-specific training after moving overseas (for example, respondents 44, 80, 156). By contrast, reliable connections to overseas jobs are scarce and thus overwhelmingly desired in Mizoram’s isolated economy. At endline, just 3 percent of the control group had worked overseas, and all of them had returned to Mizoram by the endline survey.

Second, quantitative evidence from the survey strongly and consistently shows that job training by itself had little effect on economic standing or political attitudes (Appendix E). Controlling for pretreatment covariates and for migration abroad, there were no significant differences between those who attended job training programs and those who did not, either in the treatment or the control group.

COVID-19 Shutdowns

Given that our program timeline (August 2018 to March 2021) included the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, a third possibility is that the effects we observe are due in part to differential effects of COVID shutdowns. But we find little evidence that shutdowns affected the economic standing of the treatment and control groups differently. Asked about COVID-related shutdowns, the treatment and control groups were about equally likely to have been laid off (15 versus 18 percent), had work temporarily suspended (32 versus 32 percent), and had their hours or wages cut (23 versus 22 percent). Even at the endline survey, which was conducted during the peak of India’s 2021 shutdowns, there was no significant difference between the overall employment rate of the treatment and control groups (43 versus 39 percent). Instead, the economic effects were driven by the income differences between employed individuals in the treatment and control groups, which are much less likely to have been COVID-related.

Discussion

Representativeness and External Validity

How well do these findings generalize to other migrant populations and migration corridors? We make three sets of observations, and expand on them in Appendix G.

Representativeness. First, our population and context are broadly similar to that of overseas migration from India—the world’s largest source of emigrants—and other Global South countries. Appendix G.1 compares our experimental sample with nationally representative survey data from the Indian Human Development Survey, as well as more detailed data on India’s highest out-migration region from the Kerala Migration Study. The people in our study are demographically similar to other Indian migrants in three key respects: they are disproportionately young, highly educated, and members of religious and ethnic minority groups. Furthermore, our study leverages a migration corridor that represents a large proportion of worldwide migration flows. Economic migrants to the Gulf, mostly from South Asia, make up about one in six migrants globally.Footnote 81

External validity to different subjects. Next, we examine how the findings from our particular experimental sample generalize to demographically different migrant population groups. For example, young, educated members of marginalized groups might see particularly large economic gains (and therefore large attitudinal effects) from migration, where they can put their skills to productive use free from domestic barriers to upward mobility.Footnote 82 In Appendix G.2, we look for heterogeneous effects within our sample as a test of potential generalizability to populations with a different mix of demographic traits.Footnote 83 We find no evidence that treatment effects vary by pretreatment age, education, income, minority status, or other measures of marginalization. Then we use a machine-learning algorithm to estimate individual-level treatment effects agnostically for all subjectsFootnote 84 and find no evidence of any significant heterogeneity. Taken together, these analyses suggest that our treatment would have similar effects for populations with different demographic profiles, including those from less marginalized groups.