When the Arab faith mingled with Persia, India, and the remnant of the classical world it had overrun, and Muslim civilization was the central civilization of the West.

1.1 The Roman Paradox

Here is a paradox: conventionally, the Roman Empire has been understood in the light of Europe. Yet the defining characteristic of the European experience is normally taken precisely to be the absence of a unifying empire, Roman style. All attempts to subject the many polities of the continent to a new universal empire came to naught. Where the Romans had once created unity, the Europeans maintained division. The history of Europe took shape in a process that Walter Scheidel has summarized with the pithy formula of escape – escape from the Roman condition.Footnote 1 To be sure, Rome has found many eager emulators through the centuries. European kings and state-building elites mirrored themselves in the glories of the Roman past, staged their appearance in an architectural language inspired by the imperial monuments of the Caesars and graced their ambience with forms of art drawing heavily on Greco-Roman models. But however much the ruling classes liked to parade their achievements against the backdrop of Roman history, they all failed to follow in the footsteps of their ancient predecessor in the most important respect: they were unable to overcome their main rivals, extend power across Europe and impose an imperial peace.

London, Paris, Berlin or Rome – during the nineteenth century all were appointed with classicizing imperial monuments such as the Arc de Triomphe, Trafalgar Square, Brandenburger Tor or the stupefying Vittorio Emmanuele Monument, often referred to as the altare della patria (Fig. 1.1). Significantly, however, these iconic landmarks were erected as proud proclamations of national unity, modernization and greatness. In an extraordinary reversal of the historically predominant pattern, conquest and empire had been pushed to the margins. Colonies were something that nations of the European metropolis sought primarily in overseas territories far from home.Footnote 2 By contrast, ancient Rome had expanded by defeating and absorbing their closest and strongest rivals. The road to Roman world rule went over the fall of mighty Carthage and the Hellenistic successor monarchies that had emerged out of the glorious trail of conquests cut through Asia by Alexander. Nineteenth-century monuments, on the other hand, celebrated the capacity of nations to hold their own in the main theatre of military conflict and communicated their willingness to assert their position among the other great metropolitan powers of the day. In the competition of nations, no one wanted to be seen as falling behind their neighbours. If Paris saw the construction of grand symbolic architecture, London quickly answered. If a unified Germany was to be ruled by a Kaiser, the British queen would soon find herself proclaimed Imperatrix Indiae. The European neo-Romans of the nineteenth century were busy consolidating the political fragmentation which had characterized the continent since the collapse of the Western Roman court in the fifth century CE.Footnote 3

b. Arc de Triomphe (Paris, 1806–1836).

d. Altare della Patria (Rome, 1885–1935).

Occasionally the European Union is cast as a new empire seeking to impose the unity that had eluded the continent for centuries. But this is nothing more than rhetorical flourish. With or without a Brexit, the Union has been far too weak to warrant this label.Footnote 4 If anything, the fragile unity achieved by the EU rather puts into sharp relief just how much of a deviation from the historical norm the empire represents. In the experience of Europe, Rome and the empire look like an anomaly. When power ebbed away from the imperial city on the Tiber, the dwindling population, a mere fraction of its former glory, was left nestling in an oversized urban landscape of gigantic but crumbling buildings; ‘Wrecks of another world, whose ashes still are warm’, as Byron would later muse.Footnote 5 Unable to fill the void, the remaining residents were for the next many centuries able to draw on the ruins as an inexhaustible quarry to provide the materials for one phase of opulent building activity after the other. Medieval, renaissance and baroque Rome all relied on the spoliation of the imperial past.

The imperial capital had been the product of an enormous concentration of resources; it drew on a Mediterranean world empire that bestrode not merely one but three continents: Europe, Asia and Africa. Little wonder then that it does not easily map onto the European experience. Nothing in the history of pre-industrial European states quite prepares the student for ancient Rome. The imperial titan is too big, too unwieldy and simply out of all proportion to be squeezed down into a European size. Confronted with the Roman past, the compact patterns and models so familiar to students of European history frequently fall short, and their expectations serve as a poor guide to the old empire; its reality must be painted on a wider canvas. Only a turn to world history can open a reservoir of experiences and parallels of a scale vast enough to provide a match for ancient Rome.

This is what this book aims to do; it seeks to recontextualize Rome and identify a set of world-historical contexts which illuminate the ancient experience of empire. Europeans, after all, were not the only ones to reflect their experience in ancient Rome. The Ottomans, for instance, made no secret of their claim to succession from Rome. After its conquest in 1453, they deliberately chose Constantinople, the new Rome on the Bosporus, as their seat of empire. Hagia Sophia, built under Justinian as the flagship of imperial Roman Christianity, became the model for the grand mosques of Ottoman Istanbul.Footnote 6 Once, when I had to give a talk about the idea for this book, I provided an image of the Blue Mosque for a poster that my host wanted to produce to advertise the event. Probably in a hurry and just skimming the image from a small email attachment, he expressed his delight in the fact that I had chosen ‘Hagia Sophia’ (Fig. 1.2). The mistake is, at least, suggestive and may be taken as a good omen for this project. Reaching in similar fashion across three continents, the Ottomans open a window to a world of Afro-Eurasian state and empire formation that represents a set of parallel, traditionally neglected but all the more illuminating experiences and contexts for Roman history.

1.2 The Challenge of the New World History

Over the last generation, world history has been one of the most dynamic fields within the wider discipline. A spate of new works has emerged to question the shape of world history, tracing global connections and intensively debating what global and world history could mean.Footnote 7 Yet the response to this vibrant development from most classicists has been hesitant. ‘Global history is a difficult topic’, remarked Hartmut Leppin, perhaps sometimes even perceived as an existential threat.Footnote 8 Formerly, the study of the Greeks and Romans had nestled comfortably within the reigning narrative that used to structure knowledge in Western academic institutions. When charted on a map, world history took the shape of what might be labelled as the progressive crescent. After early beginnings in the ancient Near East, the story moved west into the Mediterranean with the rise of Greece and Rome, then curved up into France during the Middle Ages before Britain finally received the baton of progress to create the modern world. Only at this point did history begin to include the rest of the planet as it fell subject to European colonialism. World history, in short, had quickly left Asia and Africa behind to progress through stages of European development and eventual global domination. Ancient slavery, medieval feudalism, modern capitalism with its industry and colonies – these were the steps that to the nineteenth-century founders of the modern academic study of society summed up the course of historical evolution, and it belonged firmly in Europe. The rest of the world was perceived as stagnant and inert, outside the current of history. Marx thus devised the catch-all category of an Asiatic mode of production within which the societies without history could be grouped. Sumner Maine, the comparative legal sociologist, placed an ahistorical India, governed by caste and unchanging tradition, in opposition to the West where the development of Roman law had enabled rationality and contract to free society from the stifling dictates of hierarchy and status.Footnote 9

To a modern observer, it is obvious that this nineteenth-century narrative was a self-deceptive product of the illusions created by the age of high colonialism in which Europeans, for a very brief period, seemed able to dictate events across the planet. But if this is so, the credit is in no small part due to the critical work of Edward Said and his Orientalism. In this postcolonial classic, Said led a frontal attack on the notion of the static Orient. When Western students of Oriental societies focused on ancient texts, as if they held the key to the secret of a supposedly never-changing Middle Eastern, Indian or Chinese society, they helped forge the colonial order. Their activities created a regime of knowledge which silenced the colonial populations and served to keep them in subjection. It was the scholars staffing the Oriental faculties of Western universities who had acquired the power to define the character of the societies they were studying. The people living there were left only to express themselves in the language provided by their rulers. The solution was obvious. The Orientalist institution had to be torn down, to enable the various peoples under Western hegemony to begin to speak for themselves, developing their own story instead of having it told for them.Footnote 10

Here was a programme of liberation that passionately spoke to the conflicts, concerns and priorities of an era shaped by the dismantling of colonial empires. Decolonization had seen the emergence of a vast number of nations. Over a few decades the membership of the UN had risen from the original 51 founders in 1945 to 151 in 1978.Footnote 11 These new nations now had to find their voice and have it heard. Still, simply to leave people to tell their own story can only be half the solution, albeit a welcome and necessary one. No other continent than Europe constitutes a better warning against letting history be told solely through the eyes of one nation or ethnic group. This is a certain recipe for emphasizing the things which divide us, even elevating prejudice and bigotry to a position of truth. No one today needs to learn that we are connected across states and nations. The planet has just seen a great lockdown caused by a lethal virus spreading between societies. History has to address this dimension of human existence, too: exploring what connects us, explaining what societies have in common and seeing how they interact. How else can we understand the world which is ours? We need that kind of comparative knowledge.

Said, however, identified a significant risk in comparison and dismissed the comparative project merely as a tool of subjection, tending to narrow rather than open perspectives.Footnote 12 Too often Western thinkers had held other societies to the arbitrary standards of their own lifeworld and then found them wanting. European societies unsurprisingly in these analyses turned out to be best at being, well, European. But such unreflexive Eurocentrism was not invariably and necessarily the outcome of comparison. In combatting the stereotype of the Orient as outside history and open to domination, Said perhaps substituted another – that of an omnipotent, all-encompassing and uniform Western discourse. The polarizing and uncompromising logic of the anti-colonial struggle tended to, so to speak, wipe out nuance and vastly exaggerate the power of the colonial system, the all-important enemy and overwhelmingly significant other. Yet, however much it may have been able to influence the terms of the debate, the colonial discourse never reached the position of the hegemonic and coherent monolith portrayed in Said’s Orientalism, capable of silencing the other. Quickly, divergent and subaltern voices rose whose messages began to resonate forcefully across colonial empires – think of Gandhi and a whole string of revolutionary critics of Western power.Footnote 13

Scholarship on the Orient did not merely confirm the Eurocentric world-view, but also pushed against its boundaries, confronting it with phenomena and truths unfamiliar to the Western public. This may be illustrated by a glance at Martin Bernal’s Black Athena. The meaty volume forcefully brought Said’s agenda into the field of ancient and classical studies with a simple and clear-cut thesis: nineteenth-century European beliefs in their own exceptionalism had excluded ancient Egypt and to some extent Mesopotamia, the Orient and Africa, in short, from the prevailing narrative about the development of ancient civilization. The freedom-loving Greeks, on the other hand, were celebrated as the originators of Europe, the West and rational civilization. This stood in stark contrast to the eighteenth century, when Europeans had generally revered Egypt as a source of ancient wisdom, as in Mozart’s freemasonic opera The Magic Flute, and thus had been able to acknowledge the achievements of the South and the East.Footnote 14

Nonetheless, there is something strangely distorted about this assessment. Even as the Europeans grew increasingly (over)confident of their cultural leadership and its age-old Hellenic roots during the era of relentless colonial expansion over the nineteenth and early twentieth century, their previous certainties were constantly undermined. The story of scholarship narrated on the pages of Bernal’s book is also one of discovery and broadening horizons. For the first time in perhaps a millennium and a half, the secrets of the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and the Mesopotamian cuneiform script were unlocked. Voices, long since silenced, came to life again and described a hitherto unknown, fascinating past cultural universe teeming with stories of gods and priests, kings and queens, the meaning of life and the cultural background to the Old Testament. The Parthenon marbles or the Pergamon Altar, these glories of Hellenic culture, may have been the prize possessions of the collections of the British and Berlin Museums. Even so, following hot on their heels were the Assyrian palace reliefs, the Babylonian Ishtar Gate or the extensive displays of majestic Egyptian sculpture and mummies.Footnote 15 However, these treasured exhibits were only the tip of a much bigger iceberg.

In India, for instance, archaeology discovered the long-lost Harappa Bronze Age civilization along the Indus. By then epigraphers had already been able to date and trace the contours of the third-century BCE Mauryan Empire of Chandragupta and Ashoka. In the Americas, nineteenth- to twentieth-century Mayan archaeology uncovered a world of forgotten cities under the lush vegetation of the Mexican jungle. Within my own lifetime, the decipherment of their hieroglyphics has added written Mayan to the list of lost languages recovered from antiquity. Examples could easily be multiplied, but here we end with the early twentieth-century expeditions to the Tarim Basin that founded what is popularly known as Silk Road studies. Hidden in caves or under the sand dunes of the desert, texts and art works came to light that revealed a late antique social universe of Buddhists, Manicheans and Nestorian Christians unexpectedly rubbing shoulders in Central Asia. In short, the excavated stories and objects not only of Near Eastern but of world antiquity dramatically expanded and changed the (Western) view of the most ancient periods of human society. Vague myths and dim rumours gave way to certified chronologies and informed history.Footnote 16

As the ancient past began to take on firmer global contours, the established trajectory of Western progression began to look increasingly inadequate.Footnote 17 It may be coincidental, but the most prominent attempts to tackle this issue were made by two luminaries who were originally trained as ancient historians. But if this was a coincidence, it is unfortunately symptomatic that both have led a marginal existence inside our discipline. Both Arnold Toynbee (1889–1975) and Max Weber (1864–1920) have primarily become household names of world history and sociology, respectively. In response to the expanding panorama of world history, they developed a version that saw the course of history as consisting of the rise and decline of a long series of separate civilizations. In his multivolume A Study of History, Toynbee identified and analyzed the life cycle of no fewer than twenty-one civilizations. A towering figure in his own time, Toynbee is now little read and even less cited. His version of civilizational history, in spite of its novelty, remained anchored in nineteenth-century ideas. Each civilization was conceived as an autonomous organism, constituted the all-encompassing framework for the people living inside its area and followed more or less its own internal development as it went through its youthful, mature and old ages.Footnote 18 Instead of causal explanations, his pages are teaming with metaphors, verging almost on metaphysics.Footnote 19

Max Weber, on the other hand, is anything but forgotten. His work remains a strong influence on modern social science. Most significantly he attempted to analytically establish culture as a force in societal development. Capitalism, for instance, was not merely a product of material circumstances but shaped up to become a world-transforming force only when it was combined with Puritan Protestantism during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the Netherlands and Britain. Irrationally, the Puritan faith had shackled its worldly practitioners to a life of work without consumption. Profits were not to be enjoyed, only to be ploughed back into new business investment. Religious belief had come to sanctify the goal of capitalism: to use money to make more money. Money had ceased to be a means to an end but become the goal itself. If capitalism, therefore, was a rational activity, it was so only in a narrowly defined economic sense.

For the same reason, Western civilization could not be described, as it had by many, as simply rational in contrast to the other civilizations. In a vast comparative exercise studying religion in China, India and Judaism, Weber emphasized that the other world religions, the backbone of the other civilizations, were no less rational than modern European, Christian civilization. There was no absolute divide, and Weber’s historical sociology is packed with comparisons based on the observation of fundamental societal similarities between the great agrarian civilizations of Afro-Eurasia. Nevertheless, the fundamental question to Weber remained that of modernity. Ultimately his comparisons end up stressing a number of specific features that had enabled the Western Europe of his own time to develop what he saw as rational industrial capitalism. The other great societies had lacked these few specific features, but they had developed forms of rational thought and organization along different lines.Footnote 20

Even as Weber’s work in some respects represented a challenge to the hegemonic understanding of world history as tracing an arc of Western progress, it thus still ended up reinforcing the established narrative. Written over the first two decades of the twentieth century, it probably was as far as one could push our mental horizon. European and Western predominance, after all, was a well-established fact that no one could ignore at the time. By the 1970s and 1980s, however, the nineteenth-century edifice that had held the various elements in the traditional world-historical narrative together was crumbling. Two world wars, followed by two decades of rapid decolonization, had swept away the world of European colonialism and global hegemony. Not only had empire become illegitimate; Europe had also ceased to be the obvious centre of the world. Often Eurocentrism is denounced as a moral failing. But the issue goes far beyond the question of good or bad. It has simply become increasingly difficult to make sense of world events through a conception of history that sees Europe as the centre of the planet and the end of evolution. As new nations launched their own programmes of development, it quickly turned out that the European experience of modernization could not automatically be taken as paradigmatic for others. Their development took a different path. It was, in the programmatic statement of Dipesh Chakrabarty, time to ‘provincialise’ the European model and treat it as just one among several referential poles. The purpose, in other words, was not to throw away the forms of scholarship pursued at the modern university but to reform and build better intellectual frameworks that were more inclusive. Not only history but all the fundamental theories of social science had to be revised.Footnote 21

Enter the so-called school of historical sociology. In the 1980s a spate of path-breaking works set about re-examining the European historical experience which had served as the template for most macro-theories of social development. Three books, all hailing from the same research seminar at the London School of Economics and written by Michael Mann, John Hall and Ernest Gellner, have become classics of macro-historical enquiry. In the Sources of Social Power, Mann embarked on a journey, spanning three decades and four volumes, to supplant both Marxist and Weberian social theory. The course of human history ought not be explained by any single fundamental cause, whether economy or culture. It was the result of an interplay of several forces: political, ideological, military and economic. What decided the progressive development of human societies was the ability to combine elements of each into institutional bundles that increased the organizational capacity of collectives.

While Mann’s multivariate sociology was path-breaking and quite an eye-opener on ancient societies, his history stayed close to the dated trajectory of the progressive crescent. Empire, for instance, falls out of the narrative after the fall of Rome, only to reappear during the age of European colonialism, more than a millennium later.Footnote 22 Here his comrade in arms, John Hall, was more adventurous. His analysis of the evolution of societal power was still dominated by the rise of Europe, but his re-interrogation of the European experience took place on a background of comparative analyses of Islam, India and China. Yet each of these other great societies of the pre-industrial world were still – as a relic of the nineteenth century and Weber – treated as separate civilizations and by implication as standing outside the mainstream of history.Footnote 23 Gellner, finally, in Plough, Sword and Book, cut through these cultural distinctions to provide a brief sociological sketch of pre-industrial life, treating the various civilizations interchangeably as expressions of the same fundamental condition.Footnote 24

This trinity of works quickly received company. For our purposes, most important perhaps were the contributions by historian of Islam Patricia Crone and historian of the Byzantine Empire John Haldon. Both of them added greater depth to the portrait of pre-industrial societies in books of their own. Taken together, the efforts of the historical sociologists had managed to produce a more inclusive image of the pre-industrial and pre-colonial past.Footnote 25 Still, their analyses offered mostly static portraits and left open the question posed at the time by anthropologist Eric Wolf about Europe and the People without History. Comparative sociology had to be complemented by a turn to world history to forge a new narrative framework instead of the old.Footnote 26

Working both in parallel and in dialogue with the historical sociologists has been a steadily rising number of historians trying to cultivate world history as a field. An early trailblazer was William McNeill’s Plagues and Peoples from 1976. His fascinating discussion sketched a shared Afro-Eurasian historical framework for the last 5,000 years, shaped around the dynamic balance that existed between dense agricultural human societies and their epidemic crowd diseases.Footnote 27 A decade later this was followed by Crosby’s Ecological Imperialism and another decade on by Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel. The latter two shifted emphasis in the ecological enquiry to the question of why Europe had in the end been able to rise to global predominance and settle large tracts of the planet with colonists. They found the answer in the pool of germs, plants and domesticated animals that cohabited with human populations across Afro-Eurasia. When brought by Europeans to the Americas and Oceania, this so-called portmanteau biota represented a deadly combination to the unaccustomed Indigenous populations, which prior to contact had both fewer diseases and domesticated animals. It was these biological agents beyond the conscious control of the Europeans that had paved the way for their success, not primarily their ‘superior’ form of culture and organization.Footnote 28

But when the question is about Europe’s rise to world hegemony, no other book has been more influential over the last generation than Kenneth Pomeranz’s The Great Divergence. This instant classic of global history undertook a sustained comparison of the economies of early-modern Europe and late imperial China. The result was a forceful attack on any lingering notions of inherent advantages of European societies in economic and social organization. Not until industrialization gained momentum at the end of the eighteenth century was it possible to detect a decisive gap between China and the West. Nothing in the centuries before had suggested that Europe was on a significantly different path of development. Whether one looked to market formation or the organization of production, European leadership was anything but obvious. China could normally match the economic level of the Euro-Atlantic world. Its eventual industrialization was a product of the fortuitous location of coal in proximity to the economic leading zones and the windfall gain of the Americas – in short, sheer luck.Footnote 29

Stated like this, the thesis was perhaps pushed to the extreme. The foundation for Pomeranz’s view had already been laid by Mark Elvin in his wonderful and imaginative Pattern of the Chinese Past and extended by Bin Wong in the eye-opening China Transformed. Both these took off from the contemporary observations of Adam Smith that eighteenth-century China had possessed a well-developed commercial economy. Still, as both noted, China was not on the brink of a breakthrough to modern conditions but rather developed into the most elaborate and successful version of a stable agrarian empire in history.Footnote 30 In comparison, European societies went through a series of three violent and chaotic rolling revolutions in state-building and military mobilization, in science, and in world trade from around 1500. Slowly these dynamics began to reinforce each other, but it took time before the effects grew strong enough radically to upend things. When European sailors began to circle the planet around 1500, they were unable to challenge the big monarchies of Asia but had to make do with setting up shop along the margins of the Indian Ocean world. After 1750, the balance of power had begun to tilt visibly in the favour of European state-making and commercial elites. Over the following century the rulers of India, the Ottoman Empire and even the mighty Qing dynasty found themselves reeling under the relentless pressure of European commercial and territorial expansion.Footnote 31 But where precisely one identifies the tipping point in the prior 250 years is a matter of the ‘small print’. Early or late, from a world history perspective, this was a short period of time and the conclusion is clear: the European rise to global hegemony during the long nineteenth century was caused by a series of relatively late developments. That is the decisive insight to come out of the Pomeranz debate, and it has been the final nail in the coffin of the Eurocentric nineteenth-century version of world history.

But what to put in its place? Before Europe, then, one would have to think of world history differently. As V. S. Naipaul reminds us in the epigraph to this chapter, one could for instance locate the Islamic world at the centre of a pre-colonial history. Even more than Islam, the historical experience of China has come to be seen as an alternative point of reference and made to serve as a central site for efforts to rethink the shape of world history and construct a more inclusive story.Footnote 32 By the time Francis Fukuyama, twenty-five years after Michael Mann, revisited the problem of social power and political order, a fundamental reorientation had taken place. Ancient China had been substituted for Greco-Roman antiquity in the narrative. With the collapse of the story of the long Western progression towards modernity, there was no preordained role for either Greeks or Romans in world history.Footnote 33 Nothing, or at most precious little, in Greco-Roman history was necessary to explain the birth of modernity, as Walter Scheidel concluded in his recent discussion.Footnote 34 This view is an obvious challenge to the field of classics and ancient history to which we must find an answer, and to do so, we must engage more intensively with the newly developing discourse on world history.Footnote 35

1.3 Towards a New Ancient World History – and a Place for Rome

The new world history, however, is still just in the making. During a recent workshop, a Chinese colleague remarked in discussion that, to him, writing China into world history meant aligning the history of the middle kingdom to the categories of European history. This was a purely pragmatic stance, and as historian of the Qing dynasty Pamela Crossley has shown in her Hammer and Anvil, it is possible to get quite far with such an approach.Footnote 36 If the differences were generally small within the pre-colonial world, what is there to prevent us from extending the well-established European chronologies to embrace the rest of Afro-Eurasia? So we have seen a global early modernity, a global middle ages, perhaps even a global late antiquity, but so far few attempts to argue for a global classical age.Footnote 37 Within this framework, a strong trend has emerged to write so-called connected histories. Under the leadership of Sanjay Subrahmanyam, this group of historians reject comparison and have instead set out in the pursuit of global connections. Their stories seek to identify liminal persons that crossed civilizational boundaries and may be presented as precursors of the cultural mixture and connectivity of modern borderless globalization.Footnote 38 Inspired by the same impulse to celebrate the global ties of cultures, the notional construct of the Silk Road has received a new lease of life. Coined during the age of high imperialism by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, fuelled by its sense of adventure and romance and vigorously promoted by China, the Silk Road attracts attention as never before. To an upbeat Peter Frankopan, it simply holds the keys to a new global history.Footnote 39 For others, it has served as a flag under which to study an ancient and medieval form of globalization built around the long-distance trade in exotic spices and rich silken fabrics running across both Central Asia and the Indian Ocean.Footnote 40 Still others have pursued the agenda of connection by looking for globalizing processes in various geographical macro-regions before the rise of Europe. The ancient Mediterranean, for instance, is then treated as showing a geographically more constricted form of globalization than the modern, culminating in the Rome Empire.Footnote 41

But these attempts to generate a history of global reach by expanding the European experience, whether in terms of chronology or the connectivity of globalization, can only be a first step. The global drive to modernise and the pressure to conform to standards set by the most successful Euro-Atlantic powers was an outgrowth of industrialization and colonial empire building. This was one of the key insights identified by C. A. Bayly in The Birth of the Modern World, a path-breaking and foundational work on the global history of the nineteenth century.Footnote 42 By writing pre-colonial history on the chronological template of European history and its competitive pressures of globalization, we inadvertently extend the moment of European global hegemony back before it was achieved. If the world was ever made to march to a tune set in Europe, it was only for a brief moment. Before the age of forced convergence, the world moved to a different rhythm. To identify that rhythm is one of the most central tasks confronting the new global history at the moment, and it means transcending the ready-to-hand frameworks based on the extension of Europe.Footnote 43 Histories of global connection must be better contextualized by comparison. The problem of Roman imperial history and the problem of world history, in other words, turn out to be the same: both must be taken out of the European mould.

However, in the absence of a clear hegemonic centre, as Hervé Inglebert recently noted, there is no unifying principle immediately available for pre-colonial world history. All that might seem possible is the pursuit of area studies, much as in the time of Toynbee, one culture or civilization at a time.Footnote 44 To be sure, in several recent world histories, the area-studies principle tends undeniably to crowd out attempts at synthesis, the further you go back in history.Footnote 45 But atomistic fragmentation is not the only alternative to a Eurocentric world history. Cultures are not self-reliant, autonomous wholes; they constantly borrow and adapt from each other. This is not a feature which emerged only with modern globalization. If premodern civilizations have sometimes seemed closed onto themselves, it is because of the way we study them. For very understandable reasons, language-learning assumes primacy, and later specialization tends to reinforce a focus on a restricted body of texts or a specific site or locality. How else could we pretend to unlock the secrets of a long gone past, if we do not apply ourselves arduously to study their often arcane languages and artistic idioms? Deep immersive learning has many strengths, but it also comes with weaknesses and blind angles of its own.

One of these is synthesis. No one can learn all the languages, after all. Most Roman historians do not even master all the written languages of the empire but make do with Latin and Greek – neither of which was used by a majority of the population – and normally feel most confident by sticking to one region or province. This means that the question about how Rome relates to other historical societies is rarely even posed. Still, language is not an absolute barrier and should not be allowed to function as a mental prison. Intercultural communication is clearly possible, as students of cosmopolitanism reminds us. After all, much in the world is ‘utterly humanly familiar’. This pragmatic observation belongs to Kwame Appiah, who continues, ‘once someone has translated the language you don’t know … you will have no more (and, of course, no less) trouble understanding’ than the things more seemingly familiar to you.Footnote 46 Marriage, kingship, religious cult, warfare – the list could be extended ad infinitum – are all institutions and forms of activity that are found in most societies. Some of their features will be specific to the particular society in which they are studied, but much is also shared across cultural boundaries, and for many aspects of past life, it is not even evident that language opens a particularly privileged path to understanding.

Historical demography and epidemiology would be one obvious case.Footnote 47 Another example would be the share of their produce that peasants have commonly had to hand over to landlords, city dwellers and rulers. Here knowledge of the constraints of agricultural production, practices of land surveying and the (military) power of lords to be gleaned from parallel historical experiences may well tell us more than fine-grained conceptual analysis of very fragmentary primary, documentary sources. The sceptic will object that the handling of such ‘secondary’ material will inevitably lead to misunderstandings, crude assessments and loss of nuance. But that is missing the point. Salman Rushdie once famously quipped that ‘it is normally supposed that something always gets lost in translation; I cling, obstinately, to the notion that something can also be gained’.Footnote 48 The thing we gain is access to a wider experience, a better understanding of commonalities and the very capacity to identify shared developments, fundamental processes and broader trends. Much, therefore, speaks in favour of pragmatism. It is not a question of either/or. World history can alternate, as I will try to demonstrate in this book, between immersive study and the broader perspective obtainable only by engaging the work of colleagues in neighbouring fields and using them as our informants and translators.

In fact, we already tacitly acknowledge the necessity of such work, but then it goes under the label of theory. Classicists and ancient historians constantly draw on theory to illuminate the Greeks and Romans.Footnote 49 Yet the general insights of current theory come with one major drawback. Most theory has been developed to explain modern industrialized or even post-industrial conditions. For a time, anthropology seemed to offer an alternative. Fanning out from Western university departments at the turn of the nineteenth century, the practitioners of the discipline sought out pockets of human society as yet untouched by the forces of modernization. Most of the communities selected by anthropologists as their object were small-scale and commonly non-state. However, as such pockets have thinned out, anthropology has increasingly, as a voice of anti-modernity, turned to studying communities that have become marginalized in or fallen victim to the processes of modern development. Whichever way, the current use of theory reflects precisely the ‘lack of a tenable framework of world history’.Footnote 50 Either you have to align the ancient experience to the modern as much as possible or you adopt models from much simpler pre-state societies. What has been missing is theory tailored to the explanatory needs of larger, pre-industrial societies that saw the formation of cities, states and empires.Footnote 51

This gap was separately identified, at a remarkable intellectual conjuncture in the late 1960s and early 1970s, by Moses Finley and Marshall Hodgson. One a towering figure in the study of the Greco-Roman world, the other of premodern Islam, both pioneered reflection on the place of their pre-industrial culture in the context of world history. To overcome the limitations of theory, what was needed, they concluded, was more comparative study, not of the cultural essences of civilizations, placing one block against the other, but of specific institutions and concrete processes of complex, citied and literate, agrarian societies.Footnote 52 Here then is a challenge left to us to step out of our comfort zone and open the lines of communication to other neighbouring disciplines studying pre-industrial societies and cultures. There should be little to make us hesitate. If we are generally comfortable spanning the enormous gap between industrial and pre-industrial conditions in our use of theory, then we should also be able to tolerate generalization across societies that on all parameters are much closer to each other. Whether we look to the economic foundations, forms of technology, modes of communication, social organization and cultural manifestations, the differences among these societies are bound to have been much smaller than what separates life in our modern global village from all of them together.

To find common ground, however, experiment is necessary.Footnote 53 Different geographical and thematic contexts will have to be explored. Afro-Eurasia, the pre-colonial Americas, what backdrops of world history are most suitable – that is the question. Inspired by the efforts of the historical sociologists, a small body of work has sprouted in ancient history over the last generation to confront the unfamiliar in a search for commonalities and shared foundations between the Greco-Roman and other pre-industrial societies. Differences are here treated as less absolute but as belonging to a repertoire of potential responses to broadly similar conditions. Finley opened the quest by focusing on Greco-Roman slavery. It is now well-established to include comparison, both with the plantation economies of the Caribbean and the ancient Near East and with other historical societies even further afield.Footnote 54

Comparative work has also been done on the city-state. Mogens Hansen, for instance, embedded his examination of the Greek polis in a wider context of more than thirty historically attested city-state cultures.Footnote 55 Kurt Raaflaub, with shifting collaborators, embarked on a broad-spectred project to generate comparative histories for the ancient world.Footnote 56 So far, however, the formation of empires has proven by far the most fertile field spawning comparisons and interdisciplinary conversation. Archaeologists of the Precolumbian Americas and South Asia have teamed up with classicists to probe the various dimensions of imperial rule. A large European research network embarked on a project to bring historians together to examine parallels among the Romans, the Ottomans, the Mughals and other similar empires.Footnote 57 No doubt reinforced by the current great power rivalry of the US and China, attempts to match the imperial experience of ancient China and Rome have grown into a sub-trend of its own.Footnote 58

If the current quest for comparison has successfully broadened horizons and the reach of the historical imagination, the effort has still primarily been an exercise in historical sociology: comparison of cases perceived as typologically similar but treated as separate.Footnote 59 A unified alternative historical framework has yet fully to be fleshed out. Ian Morris, for instance, in Why the West Rules for Now, still makes do with depicting history as a millennia-long race along a progressing Western frontier towards modernity, significantly interrupted by a long medieval interlude with China in the lead, as a concession to the revisionist historiography.Footnote 60 Meanwhile, the attempt of Sitta von Reden and her group to push beyond the Silk Roads carves out an Afro-Eurasian framework for our study of the ancient economy.Footnote 61 Out of the experiments in recontextualization, therefore, the contours of a new geographical framework and temporality are slowly becoming discernible. A unifying history may, after all, be within reach that can place the comparative examples within a shared development. But which exactly?

One of the great strengths of the pursuit of world history is its capacity to play with chronologies. Inspired by biology and geological time, big history has for instance begun to ask us to situate human society within the wider and deeper history of our planet and solar system. But for most purposes this is going too big, after all. Measured against the timescale of natural history, the human experience is but a quick flash, a day or two in the life of our planet.Footnote 62 Most societal development will be invisible from such a distant vantage point. While a scheme tailored solely to European history may be too detailed to extend across the pre-colonial world, big history is not fine-grained enough. Something in between is needed, a macro-perspective that may be able to discern some broad trends across Afro-Eurasia and the Americas before the rise of colonialism.

A survey of West Eurasian state formation from its beginnings in the early Bronze Age till the formation of the Muslim empire some three-and-a-half millennia later may point us in the right direction.Footnote 63 Whether one looks to Assur or Carthage, the pharaohs or the caliphs, it reveals a political universe of remarkably recurrent patterns. The portraits produced by historians of the many separate, individual polities that came and went over this long period of time sport surprisingly many fundamental parallels in spite of their differences. But out of this repetitive flow, two long-term trends appear that are barely perceptible on the basis of the study of each single city-state or monarchy. First, state power went through a slow but steady consolidation and amalgamation of individual polities into vast universal empires. Second, the world of state making saw an enormous expansion. Population numbers rose considerably and the extent of territory subject to state power increased several times in size. While the realm of the Egyptian pharaoh had represented the height of state power in the third millennium BCE, it had come to constitute but a single, if affluent, province of the Roman Empire by the first century CE.

However, this expansive pattern was in no way confined solely to the Middle East and Mediterranean; it can in fact be identified across Afro-Eurasia and traced beyond the accustomed chronological boundaries of antiquity. Listen to Abu Tauleb Hossaini:

There are five lofty emperors whom because of their greatness people do not refer to by their names. The emperor of Hind, they call Dara, and the emperor of Rome [Rum], they hail as Kaisar, and the Emperor of Khuttun, and Chin, and Maucheen, they name Fughfoor, and the emperor of Turkestan they mention as Kaghan and they call the lord of Eran and Turan, king of kings.Footnote 64

Penned in the Persian language by an intellectual at the court of the Great Mughals during the seventeenth century, these lines conjure a fascinating alternative vision of world history. The zone of Afro-Eurasian state making had continued to expand and is here laid out as an arena dominated by what we might loosely describe as a group of mighty imperial monarchies. The Mughals saw themselves as heirs of Teimur Lenk, the conqueror from Samarkand, and therefore ought as king of kings to govern both India and their central Asian ancestral homeland. Next to the Mughals we find the Fughfoor, the title used in Arabic to denote the Chinese emperor, and the Kaisar-i Rum, whichs although Roman in origin would have referred to the Ottoman sultan.

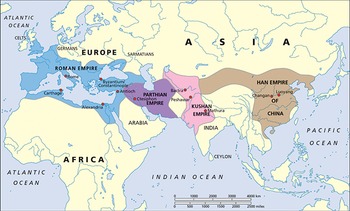

Here may well be the unifying world history framework called for by Finley, Hodgson and, in his own fashion, Inglebert. Hossaini’s image of the world encompasses a wide geographical reach and also provides the key to give meaningful chronological shape to the history of complex agrarian society (see Fig. 1.3).Footnote 65 For lack of better alternatives, world historians sometimes speak of the Axial Age. Inspired by Hegel and his notion of the spirit of history, the German philosopher Karl Jaspers once proclaimed the centuries between 800 and 200 BCE, which saw thinkers such as Confucius, Buddha and Socrates, as a world historical breakthrough to a new stage of consciousness, an axis in the development of human society.Footnote 66 Yet it is not immediately obvious how the message of Confucius in China to respect traditional hierarchies squares with the injunction of Socrates to his fellow citizens in Athens that they ceaselessly question established wisdom and customs. Whatever unity could be claimed on the basis of these thinkers is too elusive as a structuring principle for a world history. By contrast, Hossaini provides a far more concrete and materially tangible axis for a world history. The period identified by Jaspers as crucial was, more or less, the moment when grand empires begin to mushroom across the Afro-Eurasian landmass.Footnote 67

a. The arena dominated by the Qing, the Mughal and the Ottoman Empires around 1700 CE.

Figure 1.3a.Long description

In the Americas, the zones marked are Canada, Oregon, English colonies of America, New Spain, New Granada, Vice-royalty of Brazil, Vice-royalty of Peru, and Rio de la Plata. The rest of the map is covered by a zoomed section. It points out the borders of England, Spain (containing Madrid), Portugal, France, the Holy Roman Empire (containing Vienna), Poland-Lithuania, Russia (containing Moscow; borders shown up to 1619), the Ottoman Empire (containing Hungary, Algiers, Tripoli, Egypt, and Constantinople or Islamabad), the Safavid Empire (containing Isfahad), the Mughal Empire (containing Shahjahanabad or Delhi), the Qing Empire (containing Korea and Beijing or Peking), Siam, Philippines, Japan, and African regions of Songhai (by 1600), Dahomey, Benin, Bornu, Lunda, and Ethiopia. Arrows around the Qing Empire show the Manchus moving in around 1644, and the expeditions towards Mongolia in 1697, Sinkiang in 1724/1760, and Tibet in 1720. An arrow also marks the Conquest of Siberia in 1645.

b. The arena by the second century CE.

Figure 1.3b.Long description

Important cities include Rome, Carthage, Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinople in the Roman Empire, Ctesiphon in the Parthian Empire, Bactra, Peshawar, and Mathura in the Kushan Empire, and Changan and Luoyang in the Han Empire of China.

Classical Greco-Roman antiquity finds its place within the epoch in world history where the foundations of what we might call the Afro-Eurasian arena of universal empires, sketched by Hossaini, were laid. Titles such as the Persian Shahanshah or the Roman Caesar became fixtures of state-craft in precisely this period. With the rise of the Achaemenid dynasty in the mid sixth century BCE, empire broke the bounds of the ancient Levant to reach deep into central Asia and push out towards the centre of the Mediterranean. Over the next few centuries this movement gathered force. Vast empires, with rulers who saw themselves as universal and standing above other lords, began for the first time to form in a band stretching across Afro-Eurasia, from China to the shores of the Atlantic. Why this was the case is a key question of global history, and it is one in which the Roman experience has a significant role to play. But it is also a history which the thinkers of the nineteenth century had ignored and deemed outside the main current of social evolution.Footnote 68

Yet the complex of empires was far from the stagnant formation that they all envisaged it to be. To be sure, from one perspective one dynasty of conquerors might seem merely to replace the other. Still, under the endless succession of rulers, their societies continued slowly to grow in a glacially expanding drift and the texture of rule accumulated new layers. The Khagan, mentioned by Hossaini, was an addition to the ‘club’ that came at the very end of antiquity as the power of the central Asian steppe increased until it culminated in the vast and unmatched Mongol conquests of the thirteenth century CE. In antiquity, the distance was still too big between the main centres of power and the density of contacts too thin to foster a political horizon that could as a matter of course be projected across the length and breadth of the Afro-Eurasian world. A sole inscription commemorating a fledgling Kushan ruler in North India of the third century CE measures him against the Roman Caesar, the Persian king of kings, the rajas of India and just possibly one of the monarchs from the Chinese culture sphere (see Chapter 3). But that was a first. By the end of antiquity, the caliph would be able to imagine himself at the head of a procession of tributary Afro-Eurasian rulers.Footnote 69

Even so, normally the great imperial dynasties matched their achievements against their closest regional rival(s). Most famous, perhaps, are the reliefs at Naqsh-e Rostam in modern Iran depicting the Sasanian king of kings rising in solitary glory over his defeated and prostate Roman imperial opponents (See Fig. 3.1 further below). However, this is all that is needed. These regional rivalries serially linked up to form a loosely interconnected world of imperial rule and lordship stretching from the western to the eastern end of Afro-Eurasia and lasting from the onset of Achaemenid rule to the rise of European colonialism in the second half of the eighteenth century.Footnote 70 The following five chapters will explore how Rome may be seen to fit in and contribute to this story. We will embark on a journey that seeks to transcend the barriers to our neighbouring area studies in the hope of creating a sphere where we can meet in mutually beneficial dialogue.

Chapter 2 will look at state formation, ecology, peasantries and slavery; Chapter 3 examines the character of universal empires, while Chapter 4 will analyze the rise of cosmopolitan literary cultures and ecumenic religion and Chapter 5 tackles the character of intercontinental trade before the modern capitalism of European trading companies. Chapter 6 will then focus on the limits of this imperial order dominating the Afro-Eurasian world for centuries by studying the capacity of peasantries, enslaved people and populations on the margins to resist, subvert and possibly rebel against the sedentary masters. Finally, the conclusion will take stock of this experiment. What kind of world history has come out of this effort, how has Rome been recontextualized, what are the cracks in the story told here, what are the omissions and what are the alternatives? However we answer these questions, the following chapters will above all demonstrate the need to identify meaningful comparative contexts for our study of cultural connectivity. Each chapter will start with a surprising example of cultural exchange before it proceeds through comparison to identify a world history context that can invest the case with a significance beyond the merely curious, marginal and exotic, fascinating as that might be.