1. Introduction

Let k be an algebraically closed field and C a smooth, projective, and connected curve over k of genus

![]() $g \geqslant 2$

with Jacobian variety J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor of C and let

$g \geqslant 2$

with Jacobian variety J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor of C and let

![]() $\iota_e \colon C \hookrightarrow J$

be the Abel–Jacobi map based at e. We study the torsion behaviour of the Ceresa cycle

$\iota_e \colon C \hookrightarrow J$

be the Abel–Jacobi map based at e. We study the torsion behaviour of the Ceresa cycle

in the Chow group modulo rational equivalence. If

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion, then

$\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion, then

![]() $(2g-2)e= K_C$

in

$(2g-2)e= K_C$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_0(C)\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

, where

$\mathrm{CH}_0(C)\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

, where

![]() $K_C$

is the canonical divisor class. Moreover, if

$K_C$

is the canonical divisor class. Moreover, if

![]() $(2g-2)e$

is canonical, then the image of

$(2g-2)e$

is canonical, then the image of

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}$

in

$\kappa_{C,e}$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_1(J)\otimes{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is independent of e and we denote it by

$\mathrm{CH}_1(J)\otimes{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is independent of e and we denote it by

![]() $\kappa(C)$

; see § 2.7 for these claims. Thus, the class

$\kappa(C)$

; see § 2.7 for these claims. Thus, the class

![]() $\kappa(C)$

vanishes if and only if

$\kappa(C)$

vanishes if and only if

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion for some degree-1 divisor e.

$\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion for some degree-1 divisor e.

We also consider the image

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C)$

of

$\bar{\kappa}(C)$

of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

in the Griffiths group

$\kappa(C)$

in the Griffiths group

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}_1(J)\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

of homologically trivial 1-cycles modulo algebraic equivalence. When

$\mathrm{Gr}_1(J)\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

of homologically trivial 1-cycles modulo algebraic equivalence. When

![]() $g = 2$

, or more generally when C is hyperelliptic, it is easy to see that

$g = 2$

, or more generally when C is hyperelliptic, it is easy to see that

![]() $\kappa(C) = 0$

. On the other hand, Ceresa famously showed that

$\kappa(C) = 0$

. On the other hand, Ceresa famously showed that

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C) \neq 0$

for a very general curve C over C of genus

$\bar{\kappa}(C) \neq 0$

for a very general curve C over C of genus

![]() $g \geqslant 3$

[Reference CeresaCer83].

$g \geqslant 3$

[Reference CeresaCer83].

The vanishing of the Ceresa cycle is of interest for various reasons. For example,

![]() $\kappa(C) = 0$

if and only if the Chow motive

$\kappa(C) = 0$

if and only if the Chow motive

![]() ${\frak{h}}(C)$

has a multiplicative Chow–Künneth decomposition (by [Reference Fu, Laterveer and VialFLV21, Proposition 3.1] and Proposition 11). Moreover,

${\frak{h}}(C)$

has a multiplicative Chow–Künneth decomposition (by [Reference Fu, Laterveer and VialFLV21, Proposition 3.1] and Proposition 11). Moreover,

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C)=0$

if and only if the tautological subring modulo algebraic equivalence is generated by a theta divisor (by [Reference BeauvilleBea04, Corollary 3.4]), in which case Poincaré’s formula

$\bar{\kappa}(C)=0$

if and only if the tautological subring modulo algebraic equivalence is generated by a theta divisor (by [Reference BeauvilleBea04, Corollary 3.4]), in which case Poincaré’s formula

![]() $[C] = {\Theta^{g-1}}/{(g-1)!}$

holds modulo algebraic equivalence. More generally, the Ceresa cycle over

$[C] = {\Theta^{g-1}}/{(g-1)!}$

holds modulo algebraic equivalence. More generally, the Ceresa cycle over

![]() $\mathcal{M}_g$

serves as a testing ground for the study of homologically trivial algebraic cycles in codimension greater than 1.

$\mathcal{M}_g$

serves as a testing ground for the study of homologically trivial algebraic cycles in codimension greater than 1.

1.1 Vanishing criteria

We prove cohomological vanishing criteria for Ceresa cycles of curves with non-trivial automorphisms. Let

![]() $\mathrm{H}^*(-)$

be a Weil cohomology functor, such as

$\mathrm{H}^*(-)$

be a Weil cohomology functor, such as

![]() $\ell$

-adic cohomology with

$\ell$

-adic cohomology with

![]() $\ell \neq \mathrm{char \hspace{1mm}}(k)$

or singular cohomology when

$\ell \neq \mathrm{char \hspace{1mm}}(k)$

or singular cohomology when

![]() $k = \mathrm{\mathbb{C}}$

. Note that the finite group

$k = \mathrm{\mathbb{C}}$

. Note that the finite group

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

acts on

$\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

acts on

![]() $\mathrm{H}^*(J)$

, by functoriality. Cupping with the principal polarization gives an injection

$\mathrm{H}^*(J)$

, by functoriality. Cupping with the principal polarization gives an injection

![]() $\mathrm{H}^1(J)(-1) \hookrightarrow \mathrm{H}^3(J)$

, allowing us to define the primitive cohomology

$\mathrm{H}^1(J)(-1) \hookrightarrow \mathrm{H}^3(J)$

, allowing us to define the primitive cohomology

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}} := \mathrm{H}^3(J)/\mathrm{H}^1(J)(-1)$

.

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}} := \mathrm{H}^3(J)/\mathrm{H}^1(J)(-1)$

.

Theorem A.

If

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}}^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}}^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

![]() $\kappa(C) = 0$

.

$\kappa(C) = 0$

.

This improves on a recent result of Qiu and Zhang stating that if

![]() $(\mathrm{H}^1(C)^{\otimes 3})^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

$(\mathrm{H}^1(C)^{\otimes 3})^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

![]() $\kappa(C) = 0$

[Reference Qiu and ZhangQZ24].Footnote

1

By contrast, Theorem A requires only the weaker condition that the subrepresentation

$\kappa(C) = 0$

[Reference Qiu and ZhangQZ24].Footnote

1

By contrast, Theorem A requires only the weaker condition that the subrepresentation

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}} \subset \mathrm{H}^3(J) \simeq \bigwedge^3 \mathrm{H}^1(C) \subset \mathrm{H}^1(C)^{\otimes 3}$

has no non-trivial

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}} \subset \mathrm{H}^3(J) \simeq \bigwedge^3 \mathrm{H}^1(C) \subset \mathrm{H}^1(C)^{\otimes 3}$

has no non-trivial

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-fixed points. If the quotient

$\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-fixed points. If the quotient

![]() $C/\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

has genus 0, then our hypothesis is equivalent to

$C/\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

has genus 0, then our hypothesis is equivalent to

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

.

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

.

Our proof of Theorem A is inspired by Beauville’s proof that for the curve

![]() $y^3 = x^4 + x$

, the image of

$y^3 = x^4 + x$

, the image of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

under the complex Abel–Jacobi map vanishes [Reference BeauvilleBea21]. To achieve a vanishing result in the Chow group, we work directly with the rational Chow motive

$\kappa(C)$

under the complex Abel–Jacobi map vanishes [Reference BeauvilleBea21]. To achieve a vanishing result in the Chow group, we work directly with the rational Chow motive

![]() ${\frak{h}}^3(J)$

and make crucial use of the finite-dimensionality results of Kimura [Reference KimuraKim05].

${\frak{h}}^3(J)$

and make crucial use of the finite-dimensionality results of Kimura [Reference KimuraKim05].

Our second result is a vanishing criterion for

![]() $\overline{\kappa}(C)$

; however, the result is conditional on the Hodge conjecture. In particular, we assume for the rest of this introduction that k has characteristic 0.

$\overline{\kappa}(C)$

; however, the result is conditional on the Hodge conjecture. In particular, we assume for the rest of this introduction that k has characteristic 0.

Theorem B.

Assume the Hodge conjecture for abelian varieties. If

![]() $\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

$\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

, then

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C) = 0$

.

$\bar{\kappa}(C) = 0$

.

More precisely, we require the Hodge conjecture for

![]() $J\times A$

, where A is the abelian variety described in Proposition 3.3. Note that

$J\times A$

, where A is the abelian variety described in Proposition 3.3. Note that

![]() $\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3) \simeq \bigwedge^3\mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1)$

, so the conditions of Theorems A and B both depend only on the abstract representation

$\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3) \simeq \bigwedge^3\mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1)$

, so the conditions of Theorems A and B both depend only on the abstract representation

![]() $(G,V) = (\mathrm{Aut}(C), \mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1))$

.

$(G,V) = (\mathrm{Aut}(C), \mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1))$

.

The proof of Theorem B is in the same spirit as that of Theorem A. The Hodge conjecture is used to show that the motive

![]() ${\frak{h}}^3(J)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)}$

is isomorphic to

${\frak{h}}^3(J)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)}$

is isomorphic to

![]() ${\frak{h}}^1(A)(-1)$

, from which the algebraic triviality of

${\frak{h}}^1(A)(-1)$

, from which the algebraic triviality of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

follows.

$\kappa(C)$

follows.

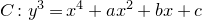

1.2 Picard curves

The condition

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}}^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

in Theorem A is only rarely satisfied; for example, it holds for exactly two plane quartic curves over C (see Theorem E below). The condition

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)_{\mathrm{prim}}^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)} = 0$

in Theorem A is only rarely satisfied; for example, it holds for exactly two plane quartic curves over C (see Theorem E below). The condition

![]() $\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)}=0$

of Theorem B is satisfied more often; for example, it holds for all Picard curves

$\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^{\mathrm{Aut}(C)}=0$

of Theorem B is satisfied more often; for example, it holds for all Picard curves

![]() $y^3 = x^4 + ax^2 + bx + c$

. 4-fold is algebraic. Fortunately, Schoen has proved the Hodge conjecture in our specific situation [Reference SchoenSch98]. (See also recent work of Markman [Reference MarkmanMar23, Reference MarkmanMar25].) This leads to an unconditional proof of the vanishing of

$y^3 = x^4 + ax^2 + bx + c$

. 4-fold is algebraic. Fortunately, Schoen has proved the Hodge conjecture in our specific situation [Reference SchoenSch98]. (See also recent work of Markman [Reference MarkmanMar23, Reference MarkmanMar25].) This leads to an unconditional proof of the vanishing of

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C)$

. By further analysing

$\bar{\kappa}(C)$

. By further analysing

![]() $\kappa(C)$

, we prove the following precise characterization of the vanishing of

$\kappa(C)$

, we prove the following precise characterization of the vanishing of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

in the Picard family.

$\kappa(C)$

in the Picard family.

Theorem C. thm: Picard main Let

![]() $C_f$

be a smooth projective Picard curve with model

$C_f$

be a smooth projective Picard curve with model

for some

![]() $a,b,c\in k$

. Consider the point

$a,b,c\in k$

. Consider the point

![]() $P_f= (a^2+12c,72ac-2a^3-27b^2)$

on the elliptic curve

$P_f= (a^2+12c,72ac-2a^3-27b^2)$

on the elliptic curve

Then

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C_f)=0$

, and

$\bar{\kappa}(C_f)=0$

, and

![]() $\kappa(C_f)=0$

if and only if

$\kappa(C_f)=0$

if and only if

![]() $P_f \in E_f(k)$

is torsion.

$P_f \in E_f(k)$

is torsion.

Here,

![]() $\mathrm{disc}(f)$

is the discriminant of f and the coordinates of

$\mathrm{disc}(f)$

is the discriminant of f and the coordinates of

![]() $P_f$

are the usual I- and J-invariants of the binary quartic form

$P_f$

are the usual I- and J-invariants of the binary quartic form

![]() $z^4 f(x/z)$

; see § 4.1. The fact that

$z^4 f(x/z)$

; see § 4.1. The fact that

![]() $P_f$

defines a point on

$P_f$

defines a point on

![]() $E_f$

follows from a classical relation between the invariants of a binary quartic. Picard curves have a unique point

$E_f$

follows from a classical relation between the invariants of a binary quartic. Picard curves have a unique point

![]() $\infty$

at infinity, for which

$\infty$

at infinity, for which

![]() $(2g-2)\infty = 4\infty$

is canonical. For a more precise version of Theorem C relating the torsion orders of

$(2g-2)\infty = 4\infty$

is canonical. For a more precise version of Theorem C relating the torsion orders of

![]() $\kappa_{C_f,\infty}$

and

$\kappa_{C_f,\infty}$

and

![]() $P_f$

, see § 4.2.

$P_f$

, see § 4.2.

Theorem C generalizes the results of [Reference Laga and ShnidmanLS25] concerning bielliptic Picard curves, that is, those with

![]() $b=0$

in (1.2). There we exploited the explicit geometry of the bielliptic cover to characterize the vanishing locus of

$b=0$

in (1.2). There we exploited the explicit geometry of the bielliptic cover to characterize the vanishing locus of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

. Here we must proceed more indirectly: using Schoen’s work on the Hodge conjecture, we first show that the vanishing of

$\kappa(C)$

. Here we must proceed more indirectly: using Schoen’s work on the Hodge conjecture, we first show that the vanishing of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

is equivalent to the vanishing of its Abel–Jacobi image in the intermediate Jacobian. Using the Shioda–Tate formula and considerations of isotrivial families of elliptic curves, we are able to bootstrap the calculations of [Reference Laga and ShnidmanLS25] to determine the Abel–Jacobi image up to a multiple and obtain the characterization of Theorem C.

$\kappa(C)$

is equivalent to the vanishing of its Abel–Jacobi image in the intermediate Jacobian. Using the Shioda–Tate formula and considerations of isotrivial families of elliptic curves, we are able to bootstrap the calculations of [Reference Laga and ShnidmanLS25] to determine the Abel–Jacobi image up to a multiple and obtain the characterization of Theorem C.

In § 3, we give several examples of higher-genus families of curves

![]() $\mathcal{C} \rightarrow B$

for which Theorem B applies. It would be interesting to completely characterize the vanishing of

$\mathcal{C} \rightarrow B$

for which Theorem B applies. It would be interesting to completely characterize the vanishing of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

in these families as well, and to find more such families. The general proof strategy would follow that of Theorem C: using the Hodge conjecture, one shows that the vanishing of

$\kappa(C)$

in these families as well, and to find more such families. The general proof strategy would follow that of Theorem C: using the Hodge conjecture, one shows that the vanishing of

![]() $\kappa(\mathcal{C}_b)$

is equivalent to the vanishing of

$\kappa(\mathcal{C}_b)$

is equivalent to the vanishing of

![]() $\sigma(b)$

, where

$\sigma(b)$

, where

![]() $\sigma$

is a section of a certain abelian scheme

$\sigma$

is a section of a certain abelian scheme

![]() $\mathcal{A} \rightarrow B$

. (The analytification of

$\mathcal{A} \rightarrow B$

. (The analytification of

![]() $\sigma$

is the normal function associated to the Ceresa cycle over B, which lands in the

$\sigma$

is the normal function associated to the Ceresa cycle over B, which lands in the

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-fixed points of the intermediate Jacobian.) One then tries to identify

$\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-fixed points of the intermediate Jacobian.) One then tries to identify

![]() $\mathcal{A} \rightarrow B$

and

$\mathcal{A} \rightarrow B$

and

![]() $\sigma$

explicitly.

$\sigma$

explicitly.

1.3 Vanishing loci in genus 3

Let

![]() $\mathcal{M}_g$

be the coarse moduli space of genus-g curves C, seen as a variety over Q. Let

$\mathcal{M}_g$

be the coarse moduli space of genus-g curves C, seen as a variety over Q. Let

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

be the locus of curves with

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

be the locus of curves with

![]() $\kappa(C) = 0$

. Let

$\kappa(C) = 0$

. Let

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

be the analogous subset for

$V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

be the analogous subset for

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C)$

. The subsets

$\bar{\kappa}(C)$

. The subsets

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

and

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

and

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

are each a countable union of closed algebraic subvarieties (Lemma 5.1). We have

$V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

are each a countable union of closed algebraic subvarieties (Lemma 5.1). We have

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}\subset V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

, and Ceresa’s result [Reference CeresaCer83] shows that

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}\subset V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

, and Ceresa’s result [Reference CeresaCer83] shows that

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{alg}} \neq \mathcal{M}_g$

for all

$V_g^{\mathrm{alg}} \neq \mathcal{M}_g$

for all

![]() $g\geqslant 3$

. What can be said about the irreducible components of

$g\geqslant 3$

. What can be said about the irreducible components of

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

and

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

and

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

and their dimensions? For a fixed g, are there only finitely many components? Collino and Pirola showed that

$V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

and their dimensions? For a fixed g, are there only finitely many components? Collino and Pirola showed that

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

does not contain subvarieties of dimension at least 4 that are not themselves contained in the hyperelliptic locus [Reference Collino and PirolaCP95, Corollary 4.3.4]. On the other hand, Theorem C shows that

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

does not contain subvarieties of dimension at least 4 that are not themselves contained in the hyperelliptic locus [Reference Collino and PirolaCP95, Corollary 4.3.4]. On the other hand, Theorem C shows that

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

contains the two-dimensional Picard locus. Turning to

$V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

contains the two-dimensional Picard locus. Turning to

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

, we answer several open question about its geometry and arithmetic by analysing the torsion locus of the section

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

, we answer several open question about its geometry and arithmetic by analysing the torsion locus of the section

![]() $P_f$

of

$P_f$

of

![]() $E_f$

.

$E_f$

.

Theorem D.

Let

![]() $X\subset \mathcal{M}_3$

be the Picard locus.

$X\subset \mathcal{M}_3$

be the Picard locus.

-

(i) The base change

$(X\cap V_3^{\mathrm{rat}})\times_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}} \mathbb{C}$

is a countably infinite disjoint union of rational curves. In particular, there exist one-parameter families of plane quartic curves in

$(X\cap V_3^{\mathrm{rat}})\times_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}} \mathbb{C}$

is a countably infinite disjoint union of rational curves. In particular, there exist one-parameter families of plane quartic curves in

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

, and

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

, and

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

contains infinitely many positive-dimensional components.

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

contains infinitely many positive-dimensional components. -

(ii) If K is a number field and

$C \in (X \cap V_3^{\mathrm{rat}})(K)$

, then the order of

$C \in (X \cap V_3^{\mathrm{rat}})(K)$

, then the order of

$\kappa_{C,\infty}$

in

$\kappa_{C,\infty}$

in

$\mathrm{CH}_1(J)$

is bounded above by a quantity depending only on

$\mathrm{CH}_1(J)$

is bounded above by a quantity depending only on

$[K\colon \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}]$

.

$[K\colon \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}]$

.

An example of a one-parameter family as in (i) is the family

![]() $C_t \colon y^3 = x^4 -12x^2 + tx -12$

. Note that we have previously shown in [Reference Laga and ShnidmanLS25, Theorem 1.3] that the torsion orders of the classes

$C_t \colon y^3 = x^4 -12x^2 + tx -12$

. Note that we have previously shown in [Reference Laga and ShnidmanLS25, Theorem 1.3] that the torsion orders of the classes

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}$

, where C has genus 3 and

$\kappa_{C,e}$

, where C has genus 3 and

![]() $4e= K_C$

, are unbounded.

$4e= K_C$

, are unbounded.

Recall that there is a stratification of the non-hyperelliptic locus of

![]() $\mathcal{M}_3$

by locally closed subvarieties

$\mathcal{M}_3$

by locally closed subvarieties

![]() $X_G$

, indexed by certain finite groups G, with the property that a non-hyperelliptic curve

$X_G$

, indexed by certain finite groups G, with the property that a non-hyperelliptic curve

![]() $[C]\in \mathcal{M}_3(\mathrm{\mathbb{C}})$

lies in

$[C]\in \mathcal{M}_3(\mathrm{\mathbb{C}})$

lies in

![]() $X_G$

if and only if

$X_G$

if and only if

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C)\simeq G$

. It turns out that the isomorphism class of the

$\mathrm{Aut}(C)\simeq G$

. It turns out that the isomorphism class of the

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-representation

$\mathrm{Aut}(C)$

-representation

![]() $\mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1)$

does not depend on the choice of curve [C] in

$\mathrm{H}^0(C, \Omega_C^1)$

does not depend on the choice of curve [C] in

![]() $X_G(\mathrm{\mathbb{C}})$

. Our final theorem determines exactly which

$X_G(\mathrm{\mathbb{C}})$

. Our final theorem determines exactly which

![]() $X_G$

are contained in

$X_G$

are contained in

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

or

$V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

or

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

.

$V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

.

Theorem E. Let G be a finite group isomorphic to the automorphism group of a plane quartic. Then

![]() $X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

if and only if

$X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

if and only if

![]() $G=C_9$

or

$G=C_9$

or

![]() $G_{48}$

, and

$G_{48}$

, and

![]() $X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

if and only if

$X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

if and only if

![]() $X_G$

is contained in the Picard locus, in other words if and only if

$X_G$

is contained in the Picard locus, in other words if and only if

![]() $G= C_3,C_6,C_9$

or

$G= C_3,C_6,C_9$

or

![]() $G_{48}$

.

$G_{48}$

.

Here,

![]() $G_{48}$

is the group with GAP label (48,33). The strata

$G_{48}$

is the group with GAP label (48,33). The strata

![]() $X_{C_{9}}$

and

$X_{C_{9}}$

and

![]() $X_{G_{48}}$

are single closed points, represented by the curves

$X_{G_{48}}$

are single closed points, represented by the curves

![]() $y^3= x^4+x$

and

$y^3= x^4+x$

and

![]() $y^3 = x^4+1$

, respectively.

$y^3 = x^4+1$

, respectively.

Theorem E shows that

![]() $X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

if and only if

$X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

if and only if

![]() $\mathrm{H}^3(J)^G=0$

for every (equivalently, some) curve in

$\mathrm{H}^3(J)^G=0$

for every (equivalently, some) curve in

![]() $X_G$

, and that

$X_G$

, and that

![]() $X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

if and only if

$X_G\subset V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

if and only if

![]() $\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^G=0$

for every curve in

$\mathrm{H}^0(J, \Omega_J^3)^G=0$

for every curve in

![]() $X_G$

. Thus, for

$X_G$

. Thus, for

![]() $g = 3$

, the criteria of Theorems A and B exactly single out the strata

$g = 3$

, the criteria of Theorems A and B exactly single out the strata

![]() $X_G$

where

$X_G$

where

![]() $\kappa(C)$

or

$\kappa(C)$

or

![]() $\bar{\kappa}(C)$

identically vanishes. Does this continue to hold in higher genera? Are there non-hyperelliptic curves of arbitrarily large genus for which Theorem A or B applies?

$\bar{\kappa}(C)$

identically vanishes. Does this continue to hold in higher genera? Are there non-hyperelliptic curves of arbitrarily large genus for which Theorem A or B applies?

We also use Theorem B to find the first examples of positive-dimensional components of

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

with generic point satisfying

$V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}$

with generic point satisfying

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C) = \{1\}$

.Footnote

2

This uses the following fact: if C dominates another curve D, then

$\mathrm{Aut}(C) = \{1\}$

.Footnote

2

This uses the following fact: if C dominates another curve D, then

![]() $\overline{\kappa}(C)=0$

implies

$\overline{\kappa}(C)=0$

implies

![]() $\overline{\kappa}(D) = 0$

. For example, the genus 6 family

$\overline{\kappa}(D) = 0$

. For example, the genus 6 family

admits a

![]() $D_9$

-action and lies in

$D_9$

-action and lies in

![]() $V_6^{\mathrm{alg}}$

(conditional on the Hodge conjecture). The quotient by the involution

$V_6^{\mathrm{alg}}$

(conditional on the Hodge conjecture). The quotient by the involution

![]() $(x,y) \mapsto (-x,y^{-1})$

is the genus-3 family

$(x,y) \mapsto (-x,y^{-1})$

is the genus-3 family

where

![]() $u = (t-1)/(t+1)$

, which lies in

$u = (t-1)/(t+1)$

, which lies in

![]() $V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

by the fact above, and satisfies

$V_3^{\mathrm{alg}}$

by the fact above, and satisfies

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(X_u) = \{1\}$

generically. A similar construction gives a one-dimensional component of

$\mathrm{Aut}(X_u) = \{1\}$

generically. A similar construction gives a one-dimensional component of

![]() $V_4^{\mathrm{alg}}$

(again conditional on the Hodge conjecture) with trivial generic automorphism group; see Theorem 3.12. Thus, even in genus 3, the implications of Theorems A and B are not yet fully understood, since it is hard to know which curves admit high-genus covers that satisfy our vanishing criteria. We should remark that, as far as we know, there are no known examples of curves C with

$V_4^{\mathrm{alg}}$

(again conditional on the Hodge conjecture) with trivial generic automorphism group; see Theorem 3.12. Thus, even in genus 3, the implications of Theorems A and B are not yet fully understood, since it is hard to know which curves admit high-genus covers that satisfy our vanishing criteria. We should remark that, as far as we know, there are no known examples of curves C with

![]() $\overline{\kappa}(C) = 0$

,

$\overline{\kappa}(C) = 0$

,

![]() $\mathrm{Aut}(C) = \{1\}$

, and

$\mathrm{Aut}(C) = \{1\}$

, and

![]() $\mathrm{End}(J) = \mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}$

; see [Reference Ellenberg, Logan and SrinivasanELS24] for data confirming this for many quartic plane curves. The curves

$\mathrm{End}(J) = \mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}$

; see [Reference Ellenberg, Logan and SrinivasanELS24] for data confirming this for many quartic plane curves. The curves

![]() $X_u$

are no exceptions as generically we have

$X_u$

are no exceptions as generically we have

![]() $\mathrm{End}^0(\mathrm{Jac}(X_u)) = \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}(\zeta_9 + \zeta_9^{-1})$

by Remark 3.13.

$\mathrm{End}^0(\mathrm{Jac}(X_u)) = \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}(\zeta_9 + \zeta_9^{-1})$

by Remark 3.13.

Finally, Gao and Zhang have recently proven a Northcott property for the Beilinson–Bloch height of the Ceresa cycle on J and (equivalently) the modified diagonal cycle

![]() $\Delta(C)$

on

$\Delta(C)$

on

![]() $C^3$

[Reference Gao and ZhangGZ24]. More precisely, for each

$C^3$

[Reference Gao and ZhangGZ24]. More precisely, for each

![]() $g \geqslant 3$

, there exists an open dense subset

$g \geqslant 3$

, there exists an open dense subset

![]() $U_g \subset \mathcal{M}_g$

such that for any

$U_g \subset \mathcal{M}_g$

such that for any

![]() $X \in \mathrm{\mathbb{R}}$

and

$X \in \mathrm{\mathbb{R}}$

and

![]() $d \in \mathrm{\mathbb{N}}$

, the number of

$d \in \mathrm{\mathbb{N}}$

, the number of

![]() $C \in U_g(\bar{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}})$

defined over a number field of degree at most d and with

$C \in U_g(\bar{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}})$

defined over a number field of degree at most d and with

![]() $\langle \Delta(C), \Delta(C)\rangle < X$

is finite. In order to better understand Ceresa vanishing loci in families of curves, it is of great interest to try to identify the largest such open dense set

$\langle \Delta(C), \Delta(C)\rangle < X$

is finite. In order to better understand Ceresa vanishing loci in families of curves, it is of great interest to try to identify the largest such open dense set

![]() $U_g$

, or equivalently, its complement

$U_g$

, or equivalently, its complement

![]() $Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}} := \mathcal{M}_g \setminus U_g$

. The Northcott property implies that any positive-dimensional component of

$Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}} := \mathcal{M}_g \setminus U_g$

. The Northcott property implies that any positive-dimensional component of

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

is contained in

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

is contained in

![]() $Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}}$

, but

$Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}}$

, but

![]() $Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}}$

may be strictly larger than the union of the positive-dimensional components of

$Z_g^{\mathrm{slim}}$

may be strictly larger than the union of the positive-dimensional components of

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

. Indeed, Theorem D shows that

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}}$

. Indeed, Theorem D shows that

![]() $X_{C_3} \subset Z_3^{\mathrm{slim}}$

, even though

$X_{C_3} \subset Z_3^{\mathrm{slim}}$

, even though

![]() $X_{C_3} \not\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

.

$X_{C_3} \not\subset V_3^{\mathrm{rat}}$

.

1.4 Structure of paper

In § 2 we collect some standard results on Chow groups, Chow motives and Ceresa cycles. In § 3 we prove the cohomological vanishing criteria (Theorems A and B) and give some examples. In § 4 we study the family of Picard curves in detail and prove Theorems C and D. Finally, in § 5 we introduce the Ceresa vanishing loci

![]() $V_g^{\mathrm{rat}},V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

, prove Theorem D and determine which automorphism strata they contain in genus 3, proving Theorem E.

$V_g^{\mathrm{rat}},V_g^{\mathrm{alg}}\subset \mathcal{M}_g$

, prove Theorem D and determine which automorphism strata they contain in genus 3, proving Theorem E.

2. Notation and background

2.1 Chow groups

Let k be a field. A variety is by definition a separated scheme of finite type over k. We say a variety is nice if it is smooth, projective and geometrically integral. If X is a smooth and geometrically integral variety and

![]() $p\in \{0,\dots,\dim X\}$

, let

$p\in \{0,\dots,\dim X\}$

, let

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

denote the Chow group (with Z-coefficients) of codimension p cycles modulo rational equivalence. If

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

denote the Chow group (with Z-coefficients) of codimension p cycles modulo rational equivalence. If

![]() $Z\subset X$

is a closed subscheme of codimension p, we denote its class in

$Z\subset X$

is a closed subscheme of codimension p, we denote its class in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

by [Z] (using [Sta18, Tag 02QS] if Z is not integral).

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

by [Z] (using [Sta18, Tag 02QS] if Z is not integral).

If X is additionally projective, then

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

has a filtration by subgroups

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

has a filtration by subgroups

where

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

is the subgroup of algebraically trivial cycles (in the sense of [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, § 3.1]) and

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

is the subgroup of algebraically trivial cycles (in the sense of [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, § 3.1]) and

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{hom}}$

the subgroup of homologically trivial cycles (with respect to a fixed Weil cohomology theory for nice varieties over k). The Griffiths group is by definition

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{hom}}$

the subgroup of homologically trivial cycles (with respect to a fixed Weil cohomology theory for nice varieties over k). The Griffiths group is by definition

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}^p(X) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{hom}}/\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

. We occasionally write

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{hom}}/\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

. We occasionally write

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_p(X) = \mathrm{CH}^{\dim X -p}(X)$

and

$\mathrm{CH}_p(X) = \mathrm{CH}^{\dim X -p}(X)$

and

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}_p(X) = \mathrm{Gr}^{\dim X -p}(X)$

. If R is a ring, we write

$\mathrm{Gr}_p(X) = \mathrm{Gr}^{\dim X -p}(X)$

. If R is a ring, we write

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_R= \mathrm{CH}^p(X)\otimes_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}} R$

and

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_R= \mathrm{CH}^p(X)\otimes_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}} R$

and

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_R = \mathrm{Gr}^p(X)\otimes_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}} R$

.

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_R = \mathrm{Gr}^p(X)\otimes_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Z}}} R$

.

2.2 Base change, specialization and families

We state three lemmas concerning operations on cycles. These seem to be standard, but we could not locate proofs in the literature.

Lemma 2.1. Let

![]() $X/k$

be a nice variety and

$X/k$

be a nice variety and

![]() $K/k$

a (not necessarily finite) extension of fields.

$K/k$

a (not necessarily finite) extension of fields.

-

(i)The base-change maps

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

and

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

and

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}\rightarrow \mathrm{Gr}^p(X_K)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

are injective.

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}\rightarrow \mathrm{Gr}^p(X_K)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

are injective.

-

(ii)If in addition k is algebraically closed, the base-change maps

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

and

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

and

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)\rightarrow \mathrm{Gr}^p(X_K)$

are injective.

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)\rightarrow \mathrm{Gr}^p(X_K)$

are injective.

Proof. The proof is an adaptation of [Reference BlochBlo10, Lemma 1A.3, p.22]. We first prove (ii) for

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

. Suppose

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

. Suppose

![]() $\alpha\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

has trivial image in

$\alpha\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

has trivial image in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

. Then

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

. Then

![]() $\alpha$

already has trivial image in

$\alpha$

already has trivial image in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{K'})$

, where

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{K'})$

, where

![]() $K'\subset K$

is a subfield that is finitely generated over k, since the data witnessing triviality in

$K'\subset K$

is a subfield that is finitely generated over k, since the data witnessing triviality in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

can be defined over such a subfield. By spreading out, we can find a smooth integral variety

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)$

can be defined over such a subfield. By spreading out, we can find a smooth integral variety

![]() $U/k$

with function field K’ such that

$U/k$

with function field K’ such that

![]() $\alpha$

has trivial image in

$\alpha$

has trivial image in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U)$

. Since k is algebraically closed, there exists a k-point

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U)$

. Since k is algebraically closed, there exists a k-point

![]() $u\in U(k)$

. Pulling back along u defines a left-inverse

$u\in U(k)$

. Pulling back along u defines a left-inverse

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

to the map

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

to the map

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U)$

. It follows that

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X\times_k U)$

. It follows that

![]() $\alpha$

is trivial in

$\alpha$

is trivial in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, as desired. The argument for

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, as desired. The argument for

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)$

is identical and omitted.

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)$

is identical and omitted.

We now prove (i) for

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. There exists a field L containing both K and an algebraic closure

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. There exists a field L containing both K and an algebraic closure

![]() $\bar{k}$

of k. It therefore suffices to prove the two base-change maps

$\bar{k}$

of k. It therefore suffices to prove the two base-change maps

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_{\bar{k}})_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_L)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

are both injective. The first one follows from the fact that for a finite extension

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_{\bar{k}})_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_L)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

are both injective. The first one follows from the fact that for a finite extension

![]() $k'/k$

the pushforward map

$k'/k$

the pushforward map

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{k'}) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, when precomposed with the base-change map, is multiplication by

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{k'}) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, when precomposed with the base-change map, is multiplication by

![]() $[k':k]$

. The second follows from (ii). The case of

$[k':k]$

. The second follows from (ii). The case of

![]() $\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is again analogous.

$\mathrm{Gr}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is again analogous.

To discuss specialization in the next lemma, let R be a discrete valuation ring with fraction field K and residue field k. Let

![]() $X\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec} (R)$

be a smooth, projective morphism with geometrically integral fibres, so the generic and special fibres

$X\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec} (R)$

be a smooth, projective morphism with geometrically integral fibres, so the generic and special fibres

![]() $X_K$

and

$X_K$

and

![]() $X_k$

are nice varieties over K and k, respectively. In this setting, Fulton [Reference FultonFul98, § 20.3] has defined a specialization morphism

$X_k$

are nice varieties over K and k, respectively. In this setting, Fulton [Reference FultonFul98, § 20.3] has defined a specialization morphism

![]() $\mathrm{sp}\colon \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)$

for every

$\mathrm{sp}\colon \mathrm{CH}^p(X_K) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)$

for every

![]() $0\leqslant p\leqslant \dim(X_K)$

. It has the property that if

$0\leqslant p\leqslant \dim(X_K)$

. It has the property that if

![]() $Z\subset X$

is a closed integral subscheme of codimension p, flat over R, then

$Z\subset X$

is a closed integral subscheme of codimension p, flat over R, then

![]() $\mathrm{sp}([Z_K]) = [Z_k]$

.

$\mathrm{sp}([Z_K]) = [Z_k]$

.

Lemma 2.2.

In the above notation, sp sends

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

to

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

to

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

.

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

.

Proof. Let

![]() $C/K$

be a nice curve with K-points

$C/K$

be a nice curve with K-points

![]() $t_0, t_1\in C(K)$

and let

$t_0, t_1\in C(K)$

and let

![]() $Z\subset (X_K)\times_K C$

be an integral closed subscheme of codimension p, flat over C. By [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, Theorem 1] and the remarks thereafter, it suffices to prove that

$Z\subset (X_K)\times_K C$

be an integral closed subscheme of codimension p, flat over C. By [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, Theorem 1] and the remarks thereafter, it suffices to prove that

![]() $\mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}] - [Z_{t_1}]) \in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}} \otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

for each such tuple

$\mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}] - [Z_{t_1}]) \in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}} \otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

for each such tuple

![]() $(C, t_0,t_1, Z)$

.

$(C, t_0,t_1, Z)$

.

Let

![]() $\mathcal{C}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

be an integral, projective, flat, proper and regular model of C, which exists by [Reference LiuLiu02, Proposition 10.1.8]. Let

$\mathcal{C}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

be an integral, projective, flat, proper and regular model of C, which exists by [Reference LiuLiu02, Proposition 10.1.8]. Let

![]() $\mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

be the Hilbert scheme of the projective morphism

$\mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

be the Hilbert scheme of the projective morphism

![]() $X\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

. The closed subscheme Z determines a K-morphism

$X\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

. The closed subscheme Z determines a K-morphism

![]() $\alpha\colon C\rightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}$

. Since C is connected, the image of

$\alpha\colon C\rightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}$

. Since C is connected, the image of

![]() $\alpha$

is contained in an open and closed subscheme

$\alpha$

is contained in an open and closed subscheme

![]() $\mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}^{\phi}$

with fixed Hilbert polynomial. The surface

$\mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}^{\phi}$

with fixed Hilbert polynomial. The surface

![]() $\mathcal{C}$

is regular,

$\mathcal{C}$

is regular,

![]() $\mathrm{Hilb}^{\phi}_{X/R}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

is projective [Reference Altman and KleimanAK80, Corollary (2.8)] and we may view

$\mathrm{Hilb}^{\phi}_{X/R}\rightarrow \mathrm{Spec}(R)$

is projective [Reference Altman and KleimanAK80, Corollary (2.8)] and we may view

![]() $\alpha$

as a rational map

$\alpha$

as a rational map

![]() $\mathcal{C}\dashrightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}^{\phi}$

. Therefore, by [Reference LiuLiu02, Theorem 9.2.7], there exists a birational map

$\mathcal{C}\dashrightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}_{X/R}^{\phi}$

. Therefore, by [Reference LiuLiu02, Theorem 9.2.7], there exists a birational map

![]() $\widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \rightarrow \mathcal{C}$

, obtained by successively blowing up closed points in the special fibre, and an R-morphism

$\widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \rightarrow \mathcal{C}$

, obtained by successively blowing up closed points in the special fibre, and an R-morphism

![]() $\tilde{\alpha}\colon \widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \rightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}^{\phi}_{X/R}$

with generic fibre

$\tilde{\alpha}\colon \widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \rightarrow \mathrm{Hilb}^{\phi}_{X/R}$

with generic fibre

![]() $\alpha$

. In other words, there exists a closed subscheme

$\alpha$

. In other words, there exists a closed subscheme

![]() $\mathcal{Z} \subset \widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \times_R X$

, flat over

$\mathcal{Z} \subset \widetilde{\mathcal{C}} \times_R X$

, flat over

![]() $\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}$

, whose generic fibre equals Z.

$\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}$

, whose generic fibre equals Z.

The K-points

![]() $t_i\in C(K)$

extend to R-points

$t_i\in C(K)$

extend to R-points

![]() $\tilde{t}_i\colon \mathrm{Spec}(R) \rightarrow \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}$

whose reductions

$\tilde{t}_i\colon \mathrm{Spec}(R) \rightarrow \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}$

whose reductions

![]() $\bar{t}_i\in \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k(k)$

land in the smooth locus of

$\bar{t}_i\in \widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k(k)$

land in the smooth locus of

![]() $\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

. The closed subschemes

$\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

. The closed subschemes

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_{\tilde{t}_i}\subset X$

are flat over R. Therefore,

$\mathcal{Z}_{\tilde{t}_i}\subset X$

are flat over R. Therefore,

![]() $\mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}]-[Z_{t_1}]) = [\mathcal{Z}_{\bar{t}_0}] - [\mathcal{Z}_{\bar{t}_1}]$

.

$\mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}]-[Z_{t_1}]) = [\mathcal{Z}_{\bar{t}_0}] - [\mathcal{Z}_{\bar{t}_1}]$

.

By the Zariski connectedness theorem, the special fibre

![]() $\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

is connected. Consequently, by resolving irreducible components of

$\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

is connected. Consequently, by resolving irreducible components of

![]() $\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

, we can connect

$\widetilde{\mathcal{C}}_k$

, we can connect

![]() $\bar{t}_0$

to

$\bar{t}_0$

to

![]() $\bar{t}_1$

by a sequence of nice curves: there exist a finite extension

$\bar{t}_1$

by a sequence of nice curves: there exist a finite extension

![]() $k'/k$

, a collection of nice curves

$k'/k$

, a collection of nice curves

![]() $D_1, \dots,D_n$

over k’, and for each

$D_1, \dots,D_n$

over k’, and for each

![]() $1\leqslant i \leqslant n$

a pair of points

$1\leqslant i \leqslant n$

a pair of points

![]() $s_{i,1}, s_{i,2}\in D_i(k')$

and a morphism

$s_{i,1}, s_{i,2}\in D_i(k')$

and a morphism

![]() $\varphi_i\colon D_i \rightarrow \mathcal{C}_{k'}$

such that

$\varphi_i\colon D_i \rightarrow \mathcal{C}_{k'}$

such that

![]() $\varphi_1(s_{1,1}) = \bar{t}_1$

,

$\varphi_1(s_{1,1}) = \bar{t}_1$

,

![]() $\varphi_i(s_{i,2}) = \varphi_{i+1}(s_{i+1,1})$

for all

$\varphi_i(s_{i,2}) = \varphi_{i+1}(s_{i+1,1})$

for all

![]() $1\leqslant i\leqslant n-1$

, and

$1\leqslant i\leqslant n-1$

, and

![]() $\varphi_{n}(s_{n,2}) = \bar{t}_2$

. Letting

$\varphi_{n}(s_{n,2}) = \bar{t}_2$

. Letting

![]() $W^{(i)}$

be the pullback of

$W^{(i)}$

be the pullback of

![]() $\mathcal{Z}_k$

along

$\mathcal{Z}_k$

along

![]() $\varphi_i$

, we have

$\varphi_i$

, we have

Since each term

![]() $([W^{(i)}_{s_{i,1}}]- [W^{(i)}_{s_{i,2}}])$

lies in

$([W^{(i)}_{s_{i,1}}]- [W^{(i)}_{s_{i,2}}])$

lies in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{k'})_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

by definition of algebraic triviality, the same is true for their sum. Taking the pushforward along

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{k'})_{\mathrm{alg}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

by definition of algebraic triviality, the same is true for their sum. Taking the pushforward along

![]() $X_{k'} \rightarrow X_k$

, we see that

$X_{k'} \rightarrow X_k$

, we see that

![]() $[k':k] \cdot \mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}]-[Z_{t_1}]) \in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

, as desired.

$[k':k] \cdot \mathrm{sp}([Z_{t_0}]-[Z_{t_1}]) \in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

, as desired.

Remark 2.3. The proof shows that if K is perfect and k is algebraically closed, then sp even sends

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

to

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_K)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

to

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

.

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_k)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

.

Lemma 2.4. Let

![]() $X\rightarrow S$

be a smooth proper morphism of smooth varieties over a field k. Let

$X\rightarrow S$

be a smooth proper morphism of smooth varieties over a field k. Let

![]() $\alpha$

be a codimension-p cycle on X. Then the locus of points

$\alpha$

be a codimension-p cycle on X. Then the locus of points

![]() $s\in S$

such that the (Gysin) fibre

$s\in S$

such that the (Gysin) fibre

![]() $\alpha_s\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is zero (respectively, lies in

$\alpha_s\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is zero (respectively, lies in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{alg}, \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

) is a countable union of closed algebraic subvarieties of S.

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{alg}, \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

) is a countable union of closed algebraic subvarieties of S.

Proof. There exist a countable subfield

![]() $k_0\subset k$

, a smooth proper morphism

$k_0\subset k$

, a smooth proper morphism

![]() $X_0\rightarrow S_0$

of varieties over

$X_0\rightarrow S_0$

of varieties over

![]() $k_0$

and a cycle

$k_0$

and a cycle

![]() $\alpha_0$

on

$\alpha_0$

on

![]() $X_0$

whose base change to k are

$X_0$

whose base change to k are

![]() $X\rightarrow S$

and

$X\rightarrow S$

and

![]() $\alpha$

, respectively. Since

$\alpha$

, respectively. Since

![]() $k_0$

is countable,

$k_0$

is countable,

![]() $S_0$

has only countably many closed subschemes. Let

$S_0$

has only countably many closed subschemes. Let

![]() $\mathcal{F}$

be the collection of integral closed subschemes

$\mathcal{F}$

be the collection of integral closed subschemes

![]() $Z\subset S_0$

such that

$Z\subset S_0$

such that

![]() $\alpha_0$

is zero in

$\alpha_0$

is zero in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{0,\eta(Z)})_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

, where

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X_{0,\eta(Z)})_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

, where

![]() $\eta(Z)\in S_0$

denotes the generic point of Z. Then we claim that the locus of

$\eta(Z)\in S_0$

denotes the generic point of Z. Then we claim that the locus of

![]() $s\in S$

for which

$s\in S$

for which

![]() $\alpha_s\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is zero is exactly the union

$\alpha_s\in \mathrm{CH}^p(X_s)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

is zero is exactly the union

![]() $\bigcup_{Z\in \mathcal{F}} Z_k \subset S$

. This follows from Lemmas 2.1 and properties of the specialization map; we omit the details, and the similar argument for algebraic triviality.

$\bigcup_{Z\in \mathcal{F}} Z_k \subset S$

. This follows from Lemmas 2.1 and properties of the specialization map; we omit the details, and the similar argument for algebraic triviality.

2.3 Chow motives

We recall a few relevant facts about the category

![]() $\mathsf{Mot}(k)$

of (pure, contravariant) Chow motives M over k with Q-coefficients; see [Reference SchollSch94] or [Reference Murre, Nagel and PetersMNP13, § 2] for basic definitions.

$\mathsf{Mot}(k)$

of (pure, contravariant) Chow motives M over k with Q-coefficients; see [Reference SchollSch94] or [Reference Murre, Nagel and PetersMNP13, § 2] for basic definitions.

Denote the Lefschetz motive by

![]() $\mathbb{L}$

, its nth tensor power by

$\mathbb{L}$

, its nth tensor power by

![]() $\mathbb{L}^n$

, and write

$\mathbb{L}^n$

, and write

![]() $M(n) = M\otimes \mathbb{L}^n$

. Following [Reference Murre, Nagel and PetersMNP13, § 2.5], the Chow group in codimension p of M is by definition

$M(n) = M\otimes \mathbb{L}^n$

. Following [Reference Murre, Nagel and PetersMNP13, § 2.5], the Chow group in codimension p of M is by definition

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(M) = \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathsf{Mot}(k)}(\mathbb{L}^{p}, M)$

. If

$\mathrm{CH}^p(M) = \mathrm{Hom}_{\mathsf{Mot}(k)}(\mathbb{L}^{p}, M)$

. If

![]() $M = {\frak{h}}(X)$

, where X is smooth projective over k, then

$M = {\frak{h}}(X)$

, where X is smooth projective over k, then

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(M) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. (Beware that we need to take Q-coefficients on the right-hand side.) If C is a nice curve over k, a morphism

$\mathrm{CH}^p(M) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. (Beware that we need to take Q-coefficients on the right-hand side.) If C is a nice curve over k, a morphism

![]() $\varphi\colon {\frak{h}}(C)\rightarrow M(p-1)$

in

$\varphi\colon {\frak{h}}(C)\rightarrow M(p-1)$

in

![]() $\mathsf{Mot}(k)$

induces a homomorphism of abelian groups

$\mathsf{Mot}(k)$

induces a homomorphism of abelian groups

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1(\varphi)\colon \mathrm{CH}^1(C)_{\mathrm{alg},\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(M)$

. We define

$\mathrm{CH}^1(\varphi)\colon \mathrm{CH}^1(C)_{\mathrm{alg},\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}} \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^p(M)$

. We define

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(M)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

to be the union of the images of

$\mathrm{CH}^p(M)_{\mathrm{alg}}$

to be the union of the images of

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1(\varphi)$

ranging over all pairs

$\mathrm{CH}^1(\varphi)$

ranging over all pairs

![]() $(C, \varphi)$

as above. This coincides with

$(C, \varphi)$

as above. This coincides with

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}} \otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

when

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)_{\mathrm{alg}} \otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

when

![]() $M = {\frak{h}}(X)$

; see [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, Corollary 4.13].

$M = {\frak{h}}(X)$

; see [Reference Achter, Casalaina-Martin and VialACMV19b, Corollary 4.13].

Finally, we define motives of fixed points. If G is a finite group acting on a motive M, write

![]() $M^G$

for the submotive cut out by the idempotent

$M^G$

for the submotive cut out by the idempotent

![]() $({1}/{\#G})\sum_{g \in G} g_* \in \mathrm{End}(M)$

. We have

$({1}/{\#G})\sum_{g \in G} g_* \in \mathrm{End}(M)$

. We have

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(M^G) = \mathrm{CH}^p(M)^G$

. If G acts on a nice variety X, then G acts on

$\mathrm{CH}^p(M^G) = \mathrm{CH}^p(M)^G$

. If G acts on a nice variety X, then G acts on

![]() ${\frak{h}}(X)$

and

${\frak{h}}(X)$

and

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, and

$\mathrm{CH}^p(X)$

, and

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}(X)^G) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)^G\otimes {\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

$\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}(X)^G) = \mathrm{CH}^p(X)^G\otimes {\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

2.4 Chow–Künneth decomposition for abelian varieties

Let

![]() $A/k$

be a g-dimensional abelian variety. Deninger and Murre [Reference Deninger and MurreDM91, § 3] have constructed a canonical Chow–Künneth decomposition

$A/k$

be a g-dimensional abelian variety. Deninger and Murre [Reference Deninger and MurreDM91, § 3] have constructed a canonical Chow–Künneth decomposition

\begin{align}{\frak{h}}(A) = \bigoplus_{i = 0}^{2g}{\frak{h}}^i(A),\end{align}

\begin{align}{\frak{h}}(A) = \bigoplus_{i = 0}^{2g}{\frak{h}}^i(A),\end{align}

uniquely characterized by the following property: if

![]() $(n)\colon A\rightarrow A$

denotes multiplication by n, then

$(n)\colon A\rightarrow A$

denotes multiplication by n, then

![]() $(n)^*$

acts on

$(n)^*$

acts on

![]() ${\frak{h}}^i(A)$

via

${\frak{h}}^i(A)$

via

![]() $n^i$

for every integer n. On the other hand, Beauville [Reference BeauvilleBea86] has shown that there exists a direct sum decomposition

$n^i$

for every integer n. On the other hand, Beauville [Reference BeauvilleBea86] has shown that there exists a direct sum decomposition

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p(A)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} = \bigoplus_{s = p-g}^p \mathrm{CH}^p_{(s)}(A)$

, where

$\mathrm{CH}^p(A)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} = \bigoplus_{s = p-g}^p \mathrm{CH}^p_{(s)}(A)$

, where

The two decompositions are linked by the formula

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^i(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^p_{(2p-i)}(A)$

. Beauville conjectured that

$\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^i(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^p_{(2p-i)}(A)$

. Beauville conjectured that

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p_{(s)}(A) = 0$

when

$\mathrm{CH}^p_{(s)}(A) = 0$

when

![]() $s<0$

, and he proved it when

$s<0$

, and he proved it when

![]() $p \in \{0,1,g-2,g-1,g\}$

[Reference BeauvilleBea86, Proposition 3(a)].

$p \in \{0,1,g-2,g-1,g\}$

[Reference BeauvilleBea86, Proposition 3(a)].

Example 2.5. For

![]() $p = 1$

, the Beauville decomposition

$p = 1$

, the Beauville decomposition

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1(A)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} = \mathrm{CH}^1_{(0)}(A) \bigoplus \mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A)$

is the decomposition of a divisor class into symmetric and anti-symmetric classes.

$\mathrm{CH}^1(A)_\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}} = \mathrm{CH}^1_{(0)}(A) \bigoplus \mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A)$

is the decomposition of a divisor class into symmetric and anti-symmetric classes.

Lemma 2.6.

If

![]() $A/k$

is an abelian variety, then

$A/k$

is an abelian variety, then

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^1(A))_{\mathrm{alg}} = \mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^1(A))$

for all

$\mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^1(A))_{\mathrm{alg}} = \mathrm{CH}^p({\frak{h}}^1(A))$

for all

![]() $p\geqslant 0$

.

$p\geqslant 0$

.

Proof. By Lemma 2.1(1), we may assume k is algebraically closed. The only non-zero Chow group of

![]() ${\frak{h}}^1(A)$

is

${\frak{h}}^1(A)$

is

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1({\frak{h}}^1(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A)$

, the set of anti-symmetric elements of

$\mathrm{CH}^1({\frak{h}}^1(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A)$

, the set of anti-symmetric elements of

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1(A)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. The lemma follows from the fact that

$\mathrm{CH}^1(A)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. The lemma follows from the fact that

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A) = \mathrm{CH}^1(A)_{\mathrm{hom}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

and that homological and algebraic equivalence coincide for codimension-1 cycles.

$\mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(A) = \mathrm{CH}^1(A)_{\mathrm{hom}}\otimes \mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}$

and that homological and algebraic equivalence coincide for codimension-1 cycles.

2.5 The Lefschetz decomposition for abelian varieties

Let

![]() $A/k$

be an abelian variety with polarization

$A/k$

be an abelian variety with polarization

![]() $\lambda\colon A \rightarrow A^{\vee}$

. Let

$\lambda\colon A \rightarrow A^{\vee}$

. Let

![]() $\ell \in \mathrm{CH}^1_{(0)}(A)$

be the unique class satisfying

$\ell \in \mathrm{CH}^1_{(0)}(A)$

be the unique class satisfying

![]() $2\ell = (1, \lambda)^* \mathcal{P}$

, where

$2\ell = (1, \lambda)^* \mathcal{P}$

, where

![]() $\mathcal{P}\in \mathrm{Pic}(A\times A^{\vee})$

is the Poincaré bundle. Künnemann has shown [Kün93, Theorem 5.2] that intersecting with

$\mathcal{P}\in \mathrm{Pic}(A\times A^{\vee})$

is the Poincaré bundle. Künnemann has shown [Kün93, Theorem 5.2] that intersecting with

![]() $\ell^{g-i}$

induces an isomorphism

$\ell^{g-i}$

induces an isomorphism

![]() ${\frak{h}}^i(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-i}(A)(g-i)$

for all

${\frak{h}}^i(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-i}(A)(g-i)$

for all

![]() $0\leqslant i \leqslant g$

. This induces a Lefschetz decomposition of the Chow–Künneth components

$0\leqslant i \leqslant g$

. This induces a Lefschetz decomposition of the Chow–Künneth components

![]() ${\frak{h}}^i(A)$

; see [Kün93, Theorem 5.1]. We are chiefly interested in the components

${\frak{h}}^i(A)$

; see [Kün93, Theorem 5.1]. We are chiefly interested in the components

![]() ${\frak{h}}^3(A)$

and

${\frak{h}}^3(A)$

and

![]() ${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)$

when

${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)$

when

![]() $g\geqslant 2$

; in that case the Lefschetz decomposition has the form

$g\geqslant 2$

; in that case the Lefschetz decomposition has the form

![]() ${\frak{h}}^3(A) = {\frak{h}}^3_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \bigoplus \ell \cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

and

${\frak{h}}^3(A) = {\frak{h}}^3_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \bigoplus \ell \cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

and

![]() ${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A) = {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \bigoplus \ell^{g-2}\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

. It has the property that the isomorphism

${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A) = {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \bigoplus \ell^{g-2}\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

. It has the property that the isomorphism

![]() $\ell^{g-3}\colon {\frak{h}}^3(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)(g-3)$

is a direct sum of isomorphisms

$\ell^{g-3}\colon {\frak{h}}^3(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)(g-3)$

is a direct sum of isomorphisms

![]() ${\frak{h}}^3_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(A)$

and

${\frak{h}}^3_{\mathrm{prim}}(A) \rightarrow {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(A)$

and

![]() $\ell\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A) \rightarrow \ell^{g-2} {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

. Taking Chow groups, we get a decomposition

$\ell\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A) \rightarrow \ell^{g-2} {\frak{h}}^1(A)$

. Taking Chow groups, we get a decomposition

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}_{\mathrm{prim}}^{2g-3}(A))\bigoplus \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}(\ell^{g-2} \cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A))$

.

$\mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(A)) = \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}_{\mathrm{prim}}^{2g-3}(A))\bigoplus \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}(\ell^{g-2} \cdot {\frak{h}}^1(A))$

.

2.6 Beauville components of C

Consider a nice curve C of genus

![]() $g\geqslant 2$

over k with Jacobian J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor on C and embed C in J using the Abel–Jacobi map based at e, sending

$g\geqslant 2$

over k with Jacobian J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor on C and embed C in J using the Abel–Jacobi map based at e, sending

![]() $x\in C$

to the divisor class of

$x\in C$

to the divisor class of

![]() $x-e$

. Decompose

$x-e$

. Decompose

![]() $[C] = [C]_0 + \cdots + [C]_{g-1}$

with

$[C] = [C]_0 + \cdots + [C]_{g-1}$

with

![]() $[C]_s \in \mathrm{CH}_{(s)}^{g-1}(J)$

. In this subsection we analyse the component

$[C]_s \in \mathrm{CH}_{(s)}^{g-1}(J)$

. In this subsection we analyse the component

![]() $[C]_1$

more closely, whose vanishing is equivalent to the vanishing of

$[C]_1$

more closely, whose vanishing is equivalent to the vanishing of

![]() $\kappa(C)$

. Proposition 2.7 can be viewed as a determination of the ‘imprimitive part’ of

$\kappa(C)$

. Proposition 2.7 can be viewed as a determination of the ‘imprimitive part’ of

![]() $[C]_1$

.

$[C]_1$

.

For

![]() $\alpha \in \mathrm{CH}_p(J)$

and

$\alpha \in \mathrm{CH}_p(J)$

and

![]() $\beta \in \mathrm{CH}_q(J)$

, the Pontryagin product

$\beta \in \mathrm{CH}_q(J)$

, the Pontryagin product

![]() $\alpha\star \beta$

is the pushforward of

$\alpha\star \beta$

is the pushforward of

![]() $\alpha\times \beta$

under the addition map

$\alpha\times \beta$

under the addition map

![]() $J\times J\rightarrow J$

. If n is a positive integer, let

$J\times J\rightarrow J$

. If n is a positive integer, let

![]() $\alpha^{\star n}$

be the n-fold Pontryagin product of

$\alpha^{\star n}$

be the n-fold Pontryagin product of

![]() $\alpha$

with itself. Let

$\alpha$

with itself. Let

![]() $K_C\in \mathrm{CH}_0(C)$

denote the canonical divisor class and let

$K_C\in \mathrm{CH}_0(C)$

denote the canonical divisor class and let

![]() $x_e\in J(k)$

be the point corresponding to the degree-0 divisor class

$x_e\in J(k)$

be the point corresponding to the degree-0 divisor class

![]() $[(2g-2)e]-K_C$

.

$[(2g-2)e]-K_C$

.

Proposition 2.7.

We have an equality in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_{(1)}^1(J)$

:

$\mathrm{CH}_{(1)}^1(J)$

:

Here we view

![]() $[0]-[x_e]$

as an element of

$[0]-[x_e]$

as an element of

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_0(J)$

.

$\mathrm{CH}_0(J)$

.

Proof. If D is a degree-(

![]() $g-1$

) divisor class on C, let

$g-1$

) divisor class on C, let

![]() $\Theta_{D}$

be the image of the map

$\Theta_{D}$

be the image of the map

![]() $\mathrm{Sym}^{g-1}(C) \rightarrow J$

defined by

$\mathrm{Sym}^{g-1}(C) \rightarrow J$

defined by

![]() $x\mapsto [x]-D$

. Then

$x\mapsto [x]-D$

. Then

![]() $[C]^{\star (g-1)} = (g-1)![\Theta_{(g-1)e}]$

. By Riemann–Roch,

$[C]^{\star (g-1)} = (g-1)![\Theta_{(g-1)e}]$

. By Riemann–Roch,

Combining the last two sentences shows that

![]() $(-1)_*([C]^{\star (g-1)}) = [x_e]\star [C]^{\star(g-1)}$

.

$(-1)_*([C]^{\star (g-1)}) = [x_e]\star [C]^{\star(g-1)}$

.

Since the Pontryagin product sends

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^{g-p}_{(s)}(J) \times \mathrm{CH}^{g-q}_{(t)}(J)$

to

$\mathrm{CH}^{g-p}_{(s)}(J) \times \mathrm{CH}^{g-q}_{(t)}(J)$

to

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^{g-p-q}_{(s+t)}(J)$

and since

$\mathrm{CH}^{g-p-q}_{(s+t)}(J)$

and since

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1_{(s)}(J)\neq 0$

only if

$\mathrm{CH}^1_{(s)}(J)\neq 0$

only if

![]() $s\in\{0,1\}$

, we calculate that

$s\in\{0,1\}$

, we calculate that

![]() $[C]^{\star(g-1)} = [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} + (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1$

. Applying

$[C]^{\star(g-1)} = [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} + (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1$

. Applying

![]() $(-1)_*$

and

$(-1)_*$

and

![]() $[x_e]\star$

to the previous identity, we obtain

$[x_e]\star$

to the previous identity, we obtain

\begin{align*} (-1)_*[C]^{\star(g-1)} &= [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} - (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1, \\ [x_e]\star [C]^{\star(g-1)} &= [x_e]\star [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} + (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1. \end{align*}

\begin{align*} (-1)_*[C]^{\star(g-1)} &= [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} - (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1, \\ [x_e]\star [C]^{\star(g-1)} &= [x_e]\star [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} + (g-1) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1. \end{align*}

Note that

![]() $[x_e]\star$

acts trivially on

$[x_e]\star$

acts trivially on

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(J)$

since

$\mathrm{CH}^1_{(1)}(J)$

since

![]() $([x_e]-[0])\in \bigoplus_{s\geqslant 1} \mathrm{CH}^g_{(s)}(J)$

by the explicit description of the Beauville decomposition for 0-cycles [Reference BeauvilleBea86, bottom of p.649]. Equating the right-hand sides of the two centred equations proves that

$([x_e]-[0])\in \bigoplus_{s\geqslant 1} \mathrm{CH}^g_{(s)}(J)$

by the explicit description of the Beauville decomposition for 0-cycles [Reference BeauvilleBea86, bottom of p.649]. Equating the right-hand sides of the two centred equations proves that

![]() $(2g-2) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1 = [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e])$

. Since

$(2g-2) \cdot [C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1 = [C]_0^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e])$

. Since

![]() $[C]_s^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e]) \in \bigoplus_{t\geqslant s+1} \mathrm{CH}^1_{(t)}(J) = \{0\}$

for all

$[C]_s^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e]) \in \bigoplus_{t\geqslant s+1} \mathrm{CH}^1_{(t)}(J) = \{0\}$

for all

![]() $s\geqslant 1$

, it follows that

$s\geqslant 1$

, it follows that

![]() $[C]_0^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e]) = [C]^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e])$

, concluding the proof.

$[C]_0^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e]) = [C]^{\star(g-1)} \star ([0]-[x_e])$

, concluding the proof.

Corollary 2.8.

Suppose that

![]() $[C]_1=0$

in

$[C]_1=0$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_1(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Then

$\mathrm{CH}_1(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Then

![]() $(2g-2)e=K_C$

in

$(2g-2)e=K_C$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_0(C)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

$\mathrm{CH}_0(C)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

Proof. If

![]() $[C]_1=0$

, then

$[C]_1=0$

, then

![]() $[C]^{\star(g-1)} \star([0]-[x_e])=0$

by (2.3). On the other hand,

$[C]^{\star(g-1)} \star([0]-[x_e])=0$

by (2.3). On the other hand,

![]() $[C]^{\star (g-1)} = (g-1)![\Theta_{(g-1)e}]$

is multiple of a theta divisor, in the notation of the proof of Proposition 2.7. Since

$[C]^{\star (g-1)} = (g-1)![\Theta_{(g-1)e}]$

is multiple of a theta divisor, in the notation of the proof of Proposition 2.7. Since

![]() $\Theta_{(g-1)e}$

defines a principal polarization, the map

$\Theta_{(g-1)e}$

defines a principal polarization, the map

![]() $x\mapsto [\Theta_{(g-1)e + x}] - [\Theta_{(g-1 )e}] = [\Theta_{(g-1)e}]\star ([x]-[0])$

induces an isomorphism

$x\mapsto [\Theta_{(g-1)e + x}] - [\Theta_{(g-1 )e}] = [\Theta_{(g-1)e}]\star ([x]-[0])$

induces an isomorphism

![]() $\varphi\colon J(k)\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^1(J)_{\hom}$

. Since

$\varphi\colon J(k)\rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^1(J)_{\hom}$

. Since

![]() $\varphi(x_e)$

is torsion, it follows that

$\varphi(x_e)$

is torsion, it follows that

![]() $x_e\in J(k)$

is itself torsion, as desired.

$x_e\in J(k)$

is itself torsion, as desired.

The principal polarization defines an ample class

![]() $\ell\in \mathrm{CH}_{(0)}^1(J)$

, which induces a Lefschetz decomposition

$\ell\in \mathrm{CH}_{(0)}^1(J)$

, which induces a Lefschetz decomposition

![]() ${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J) = {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J) \bigoplus \ell^{g-2}\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(J)$

as in § 2.5.

${\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J) = {\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J) \bigoplus \ell^{g-2}\cdot {\frak{h}}^1(J)$

as in § 2.5.

Corollary 2.9.

Suppose that

![]() $(2g-2)e = K_C$

in

$(2g-2)e = K_C$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_0(C)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Then

$\mathrm{CH}_0(C)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Then

![]() $[C]_1 \in \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J))$

.

$[C]_1 \in \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J))$

.

Proof. By definition and the discussion in § 2.4,

![]() $[C]_1\in \mathrm{CH}_{(1)}^{g-1}(J) = \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J))$

. Since

$[C]_1\in \mathrm{CH}_{(1)}^{g-1}(J) = \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J))$

. Since

![]() $x_e$

is torsion,

$x_e$

is torsion,

![]() $(n)_*([0]-[x_e]) =0$

for some integer

$(n)_*([0]-[x_e]) =0$

for some integer

![]() $n\geqslant 1$

. The decomposition (2.2) implies that

$n\geqslant 1$

. The decomposition (2.2) implies that

![]() $[0] = [x_e]$

in

$[0] = [x_e]$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_0(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Therefore, (2.3) shows that

$\mathrm{CH}_0(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

. Therefore, (2.3) shows that

![]() $[C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1=0$

. Using properties of the

$[C]_0^{\star(g-2)} \star [C]_1=0$

. Using properties of the

![]() $\mathfrak{sl}_2$

-action on

$\mathfrak{sl}_2$

-action on

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^*(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

(in the sense of [Reference MoonenMoo09, § 1.3]), this implies that

$\mathrm{CH}^*(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

(in the sense of [Reference MoonenMoo09, § 1.3]), this implies that

![]() $\ell \cdot [C]_1 = 0$

. Since

$\ell \cdot [C]_1 = 0$

. Since

![]() $\mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J))$

equals the kernel of

$\mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}_{\mathrm{prim}}(J))$

equals the kernel of

![]() $\ell \cdot (-) \colon \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J)) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-1}(J)(1))$

, the corollary follows.

$\ell \cdot (-) \colon \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-3}(J)) \rightarrow \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}({\frak{h}}^{2g-1}(J)(1))$

, the corollary follows.

2.7 Ceresa cycles

Let

![]() $C/k$

be a nice curve of genus

$C/k$

be a nice curve of genus

![]() $g\geqslant 2$

with Jacobian J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor on C and let

$g\geqslant 2$

with Jacobian J. Let e be a degree-1 divisor on C and let

![]() $\iota_e\colon C\rightarrow J$

be the Abel–Jacobi map based at e. We define

$\iota_e\colon C\rightarrow J$

be the Abel–Jacobi map based at e. We define

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}\in \mathrm{CH}_1(J)$

using formula (1.1). Using the Beauville decomposition (2.2) to write

$\kappa_{C,e}\in \mathrm{CH}_1(J)$

using formula (1.1). Using the Beauville decomposition (2.2) to write

![]() $[C] = [\iota_e(C)] = \sum_{s=0}^{g-1} [C]_s$

with

$[C] = [\iota_e(C)] = \sum_{s=0}^{g-1} [C]_s$

with

![]() $[C]_s\in \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}_{(s)}(J)$

, we calculate that

$[C]_s\in \mathrm{CH}^{g-1}_{(s)}(J)$

, we calculate that

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_1(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

$\mathrm{CH}_1(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.

Lemma 2.10.

If

![]() $\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion, then

$\kappa_{C,e}$

is torsion, then

![]() $(2g-2)e-K_C$

is torsion.

$(2g-2)e-K_C$

is torsion.

Lemma 2.11.

If

![]() $e,e'\in \mathrm{CH}_0(C)$

are degree-1 divisors such that

$e,e'\in \mathrm{CH}_0(C)$

are degree-1 divisors such that

![]() $e-e'$

is torsion, then

$e-e'$

is torsion, then

![]() $[\iota_e(C)] = [\iota_{e'}(C)]$

and

$[\iota_e(C)] = [\iota_{e'}(C)]$

and

![]() $\kappa_{C,e} = \kappa_{C,e'}$

in

$\kappa_{C,e} = \kappa_{C,e'}$

in

![]() $\mathrm{CH}_1(J)_{\mathrm{\mathbb{Q}}}$

.