Since computational social science (CSS) was coined in 2009 (D. Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Pentland, Adamic, Aral, Barabási, Brewer and Christakis2009), it has been growing exponentially in many social science disciplines and is projected to have the potential to revolutionize social science studies (D. M. J. Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Pentland, Watts, Aral, Athey, Contractor and Freelon2020). Over the past decade, the field of nonprofit and philanthropic studies has also begun to apply computational methods, such as machine learning and automated text analysis. We start this article by explaining CSS from a research design perspective and framing its applications in studying the nonprofit sector and voluntary action. Next, we illustrate the promise of CSS for our field by applying these methods to consolidate the scholarship of nonprofit and philanthropic studies—creating a bibliographic database to cover the entire literature of the research field. The article concludes with critical reflections and suggestions. This article speaks to three audiences: (1) readers without technical background can have a structural understanding of what CSS is, and how they can integrate them into their research by either learning or collaboration; (2) technical readers can review these methods from a research design perspective, and the references cited are useful for constructing a CSS course; and (3) readers motivated to study the intellectual growth of our field can discover novel methods and a useful data source. The primary purpose of this short piece is not to exhaust all CSS methods and technical details, which are introduced in most textbooks and references cited.

Computational Social Science for Nonprofit Studies: A Toolbox of Methods

Though all empirical analysis methods are computational to some extent, why are some framed as “computational social science methods” (CSS) while others are not? Is it just a fancy but short-lived buzzword, or a new methodological paradigm that is fast evolving?

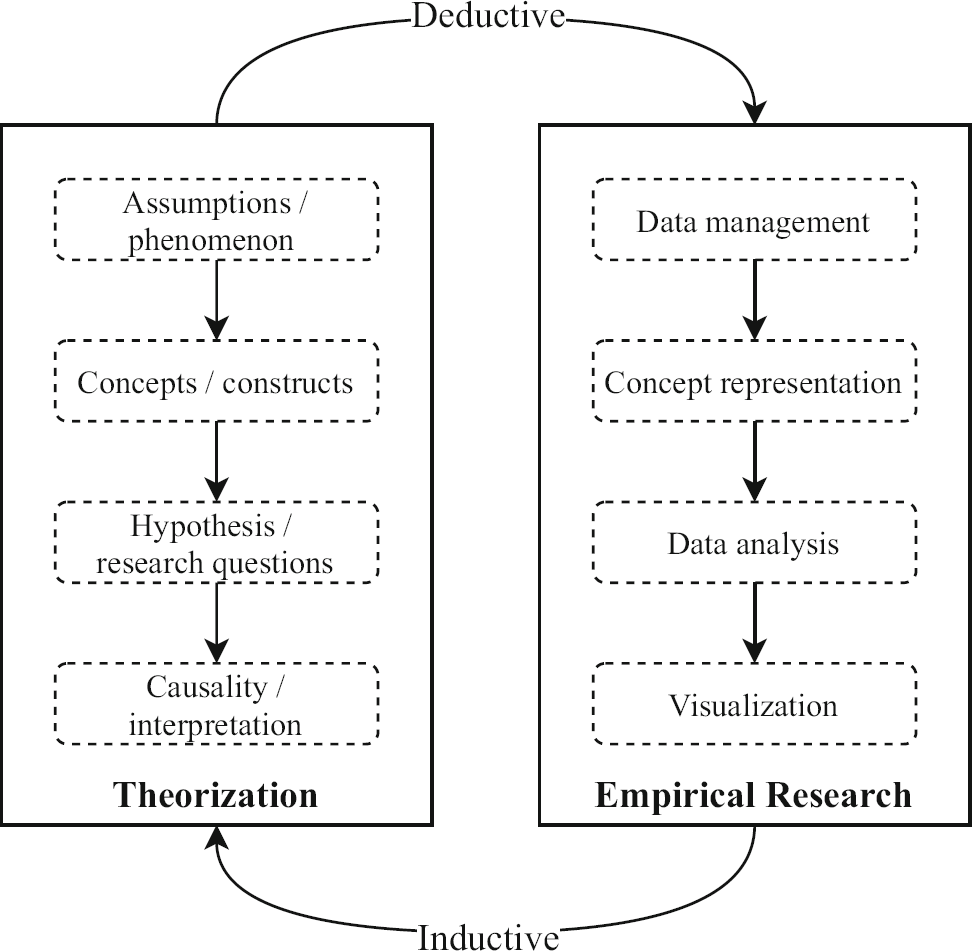

Empirical studies of social sciences typically include two essential parts: theorization and empirical research (Fig. 1; Shoemaker, Tankard, and Lasorsa Reference Shoemaker, James and Dominic2003; Ragin & Amoroso, Reference Ragin and Lisa2011, 17; Cioffi-Revilla, Reference Cioffi-Revilla2017). Theorization focuses on developing concepts and the relationship among these concepts, while empirical research emphasizes representing these concepts using empirical evidence and analyzing the relationship between concepts (Shoemaker, Tankard, and Lasorsa 2003, 51). The relationship between theorization and empirical research is bidirectional or circular—research can be either theory-driven (i.e., deductive), data-driven (i.e., inductive), or a combination of both. Quantitative and qualitative studies may vary in research paradigm and discourse, but they typically follow a similar rationale as Fig. 1 illustrates.

Fig. 1 Structure of empirical social science studies. A diagram summary of Shoemaker, Tankard, and Lasorsa (2003), adapted by the authors of this paper

CSS has been widely discussed but poorly framed—an important reason causing many scholars’ perception that the CSS is only a buzzword but not a methodological paradigm. We define CSS as a set of computationally intensive empirical methods employed in quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods social science research for data management, concept representation, data analysis, and visualization. What makes computational methods “social” is the objective to serve empirical social science research, such that theorization can have a solid ground, either by completing the deductive or the inductive cycle. What makes social science methods “computational” is the use of innovative and computationally intensive methods. The advantage of CSS for our highly interdisciplinary field is that it facilitates collaboration across traditional disciplinary borders, a promise that is being materialized in other fields of research (D. M. J. Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Pentland, Watts, Aral, Athey, Contractor and Freelon2020).

CSS methods primarily serve the four aspects of empirical research as included in Fig. 1: data management, concept representation, data analysis, and visualization. Data management methods help represent, store, and manage data efficiently. This is especially relevant when dealing with “big data”—heterogeneous, messy, and large datasets. Concept representation methods help operationalize concepts. For example, using sentiment analysis in natural language processing to scale political attitudes. These computational methods are complementary with traditional operationalizations such as attitude items in surveys or questions in interviews. Data analysis in CSS shares many statistical fundamentals with statistics (e.g., probability theory and hypothesis testing) but typically consumes more computational resources. The visualization of CSS illustrates data from multiple dimensions and using graphs that enable human–data interaction, so that consumers can closely examine the data points of interests within a massive dataset.

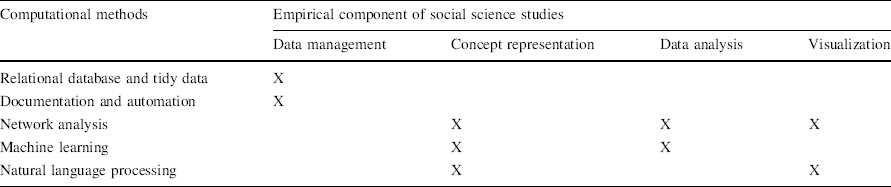

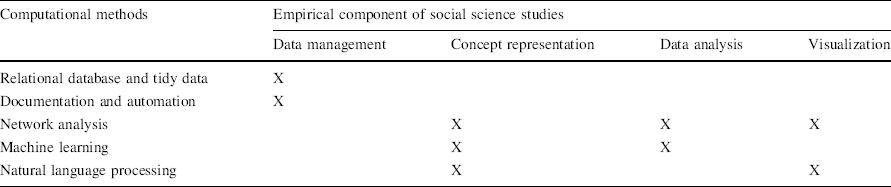

Table 1 presents a list of the most commonly used computational methods. The following sections briefly introduce them and provide applications in nonprofit studies. Our purpose is not to be comprehensive and exhaustive, but to introduce the principles behind these methods from a research design perspective in non-jargon language and within the context of nonprofit studies.

Table 1 Common computational social science methods and their roles in empirical studies

Computational methods |

Empirical component of social science studies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Data management |

Concept representation |

Data analysis |

Visualization |

|

Relational database and tidy data |

X |

|||

Documentation and automation |

X |

|||

Network analysis |

X |

X |

X |

|

Machine learning |

X |

X |

||

Natural language processing |

X |

X |

||

Data Management

Science is facing a reproducibility crisis (Baker, Reference Baker2016; Hardwicke et al., Reference Hardwicke, Wallach, Kidwell, Bendixen, Crüwell and Ioannidis2020). Since researchers using CSS methods usually deal with large volumes of data, and their analysis methods contain many parameters that need to be specified, they need to be extra cautious to reproducibility issues. Fortunately, researchers from various scientific disciplines have identified an inventory of best practices that contribute to reproducibility (Gentzkow & Shapiro, Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2014; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Bryan, Cranston, Kitzes, Nederbragt and Teal2017).

As a starting point for data management, an appropriate data structure helps represent and store real-world entities and relationships, which is fundamental to all empirical studies. Such demands can be met by using a relational database that has multiple interrelated data tables (Bachman, Reference Bachman1969; Codd, Reference Codd1970). There are two important steps for constructing such a database. First, store homogeneous data record in the same table and uniquely identify these records. Wickham (Reference Wickham2014) coined the practices of “Tidy Data,” which offer guidelines to standardize data preprocessing steps and describe how to identify untidy or messy data. Tidy datasets are particularly important for analyzing and visualizing longitudinal data (Wickham, Reference Wickham2014, 14). Second, relate different tables using shared variables or columns and represent the relationships between different tables using graphs, also known as a database schema or entity-relationship model (Chen, Reference Chen1976).

Because CSS methods heavily rely on data curation and programming languages such as Python and R, documentation and automation can improve the replicability and transparency of research (Corti et al., Reference Corti, Van den Eynden, Bishop and Woollard2019; Gentzkow & Shapiro, Reference Gentzkow and Shapiro2014). The best practices of documentation include adhering to a consistent naming convention and using a version control system such as GitHub to track changes. The primary purpose of automation is to standardize the research workflow and improve reproducibility and efficiency.

Knowledge about data management is not new, but it becomes particularly essential to nonprofit scholars in the digital age because they often deal with heterogeneous, massive, and messy data. For example, Ma et al. (Reference Ma, Qun, Chao and Huafang2017) and Ma (Reference Ma2020) constructed a relational database normalizing data on over 3,000 Chinese foundations from six different sources across 12 years. Data from different sources can be matched using codes for nonprofit organizations (De Wit, Bekkers, and Broese van Groenou Reference De Wit, Bekkers and Broese van Groenou2017) or unique countries (Wiepking et al. Reference Wiepking, Handy, Park, Neumayr, Bekkers, Breeze and de Wit2021). Without the principles of data management, it is impossible to use many open-government projects about the nonprofit sector, such as U.S. nonprofits’ tax formsFootnote 1 and the registration information of charities in the UK. Furthermore, a growing number of academic journals, publishers, and grant agencies in social sciences have started to require the public access to source codes and data. Therefore, it is important to improve students’ training in data management, as this is currently often not part of philanthropic and nonprofit studies programs.

Network Analysis

While the notion of social relations and human networks has been fundamental to sociology, modern network analysis methods only gained momentum since the mid twentieth century, along with the rapid increase in computational power (Scott, Reference Scott2017, 12–13). A network is a graph that comprises nodes (or “vertices,” i.e., the dots in a network visualization) and links (or “edges”), and network analysis uses graph theory to analyze a special type of data—the relation between entities.

Researchers typically analyze networks at different levels of analysis, for example, nodal, ego, and complete networks (Wasserman & Faust, Reference Wasserman and Faust1994, 25). At the nodal level, research questions typically focus on the attributes of nodes and how the nodal attributes are influenced by relations. At the ego network level, researchers are primarily interested in studying how the node of interest interacts with its neighbors. At the complete network level, attributes of the entire network are calculated, such as measuring the connectedness of a network. Research questions at this level usually intend to understand the relation between network structure and outcome variables. The three levels generally reflect the analyses at micro-, meso-, and macro-levels. Researchers can employ either a single-level or multi-level design, and the multi-level analysis allows scholars to answer complex sociological questions and construct holistic theories (e.g., Lazega et al., Reference Lazega, Jourda and Mounier2013; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Grund and Koskinen2018).

Nonprofits scholars have been using metrics of network analysis to operationalize various concepts. For example, the connectedness of a node or the entire network can be regarded as measuring social capital of individuals or communities (Herzog & Yang, Reference Herzog and Yang2018; Xu and Saxton Reference Xu and Saxton2019; Yang, Zhou, and Zhang Reference Yang, Zhou and Zhang2019; Nakazato & Lim, Reference Nakazato and Lim2016). Network analysis has been also applied to studying inter-organizational collaboration (Bassoli, Reference Bassoli2017; Shwom, Reference Shwom2015), resource distribution (Lai, Tao, and Cheng Reference Lai, Tao and Cheng2017), interlocking board networks (Ma & DeDeo, Reference Ma and DeDeo2018; Paarlberg, Hannibal, and McGinnis Johnson Reference Paarlberg, Hannibal and Johnson2020; Ma, Reference Ma2020), and the structure of civil societies (Seippel, Reference Seippel2008; Diani, Ernstson, and Jasny Reference Diani, Ernstson and Jasny2018). Networks can even be analyzed without real-world data. For example, Shi et al. (Reference Shi, Dokshin, Genkin and Brashears2017) created artificial network data simulating different scenarios to test how different organizational strategies affect membership rates.

Using social media data to analyze nonprofits’ online activities is a recent development with growing importance (Guo & Saxton, Reference Guo and Saxton2018; Xu and Saxton Reference Xu and Saxton2019; Bhati & McDonnell, Reference Bhati and McDonnell2020). However, social media platforms may often restrict data access because of privacy concerns, which encouraged “a new model for industry—academic partnerships” (King & Persily, Reference King and Persily2020). Researchers also have started to develop data donation projects, in which social media users provide access to their user data. For instance, Bail et al. (Reference Bail, Brown and Mann2017) offered advocacy organizations an app with insights in their relative Facebook outreach, asking nonpublic data about their Facebook page in return.

Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) can “discover new concepts, measure the prevalence of those concepts, assess causal effects, and make predictions” (Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Roberts and Stewart2021, 395; Molina & Garip, Reference Molina and Garip2019). For social scientists, the core of applying ML is to use computational power to learn or identify features from massive observations and link those features to outcomes of interest. For example, researchers only need to manually code a small subset of data records and train a ML algorithm with the coded dataset, a practice known as “supervised machine learning.” Then, the trained ML algorithm can help researchers efficiently and automatically classify the rest of the records which may be in millions. ML algorithms can also extract common features from massive numbers of observations according to preset strategies, a practice known as “unsupervised machine learning.” Researchers can then assess how the identified features are relevant to outcome variables. In both scenarios, social scientists can analyze data records that go beyond human capacity, so that they can focus on exploring the relationship between the features of input observations and outcomes of interest.

Despite these advantages, ML methods also suffer from numerous challenges. A recurrent issue is the black-box effect concerning the interpretation of results. The trained algorithms often rely on complex functions but provide little explanation on why those results are reasonable. Along with the advancement of programming languages, ML methods are becoming more accessible to researchers. However, scientists should be cautious to the parameters and caveats that are pre-specified by ML programming packages. Human validation is still the gold standard for applying ML-devised instruments in social science studies.

Although nonprofit scholars have not yet widely employed ML in their analysis, the methods have already shown a wide range of applications. For example, ML algorithms were experimented in analyzing nonprofits’ mission statements (Litofcenko, Karner, and Maier Reference Litofcenko, Karner and Maier2020; Ma, Reference Ma2021) and media’s framing of the Muslim nonprofit sector (Wasif Reference Wasif2021).

Natural Language Processing

Natural language processing (NLP) aims at getting computers to analyze human language (Gentzkow et al., Reference Gentzkow, Kelly and Taddy2019; Grimmer & Stewart, Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013). The purposes of NLP tasks can be primarily grouped into two categories for social scientists: identification and scaling. Identification methods aim at finding the themes (e.g., topic modeling) or entities (e.g., named-entity recognition) of a given text, which is very similar to the grounded theory approach in qualitative research (Baumer et al., Reference Baumer, Mimno, Guha, Quan and Gay2017). Scaling methods put given texts on a binary, categorical, or continuous scale with social meanings (e.g., liberal-conservative attitudes). Identification and scaling can be implemented through either a dictionary approach (i.e., matching target texts with a list of attribute keywords or another list of texts) or a machine learning approach. Although NLP methods are primarily developed in computational linguistics, they can also serve as robust instruments in social sciences (Rodriguez & Spirling, Reference Rodriguez and Spirling2021).

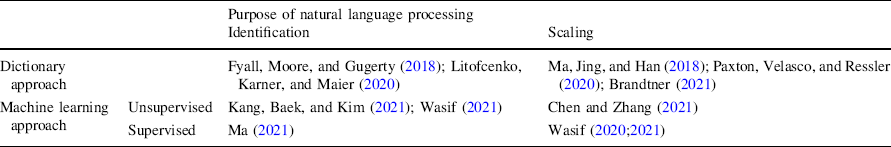

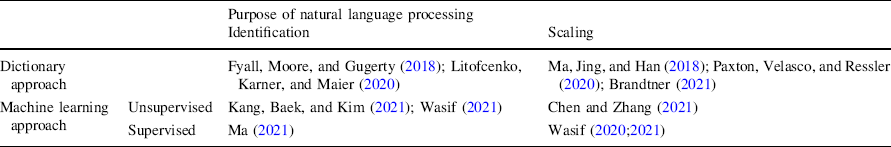

Table 2 lists empirical studies that are relevant to nonprofit and philanthropic studies. Scholars in other disciplines offer additional examples of the potential of NLP methods. For example, researchers in public administration and political science have applied sentiment analysis and topic modeling to find clusters of words and analyze meanings of political speeches, assembly transcripts, and legal documents (Mueller & Rauh, Reference Mueller and Rauh2018; Parthasarathy et al., Reference Parthasarathy, Rao and Palaniswamy2019; Anastasopoulos & Whitford, Reference Anastasopoulos and Whitford2019; Gilardi, Shipan, and Wüest Reference Gilardi, Shipan and Wüest2020). In sociology, text mining has proven useful to extract semantic aspects of social class and interactions (Kozlowski et al., Reference Kozlowski, Taddy and Evans2019; Schröder et al., Reference Schröder, Hoey and Rogers2016). As Evans and Aceves (Reference Evans and Aceves2016, 43) summarize, although NLP methods cannot replace creative researchers, they can identify subtle associations from massive texts that humans cannot easily detect.

Table 2 Example articles studying nonprofits with natural language processing methods

Purpose of natural language processing |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Identification |

Scaling |

||

Dictionary approach |

Fyall, Moore, and Gugerty (Reference Fyall, Kathleen Moore and Gugerty2018); Litofcenko, Karner, and Maier (Reference Litofcenko, Karner and Maier2020) |

Ma, Jing, and Han (Reference Ma, Jing and Han2018); Paxton, Velasco, and Ressler (Reference Paxton, Velasco and Ressler2020); Brandtner (Reference Brandtner2021) |

|

Machine learning approach |

Unsupervised |

Kang, Baek, and Kim (Reference Kang, Baek and Kim2021); Wasif (Reference Wasif2021) |

Chen and Zhang (Reference Chen and Zhang2021) |

Supervised |

Ma (Reference Ma2021) |

Applying the Methods: The Knowledge Infrastructure of Nonprofit and Philanthropic Studies

Most of the social science disciplines have dedicated bibliographic databases, for example, Sociological Abstracts for sociology and Research Papers in Economics for economics. These databases serve as important data sources and knowledge bases for tracking, studying, and facilitating the disciplines’ intellectual growth (e.g., Moody, Reference Moody2004; Goyal, van der Leij, and Moraga‐González Reference Goyal, van der Leij and Moraga-González2006).

In the past few decades, the number of publications on nonprofit and philanthropy has been growing exponentially (Shier & Handy, Reference Shier and Handy2014, 817; Ma & Konrath, Reference Ma and Konrath2018, 1145), and nonprofit scholars have also started to collect bibliographic records from different sources to track the intellectual growth of our field. For example, Brass et al. (Reference Brass, Longhofer, Robinson and Schnable2018) established the NGO Knowledge CollectiveFootnote 2 to synthesize the academic scholarship on NGOs. Studying our field’s intellectual growth has been attracting more scholarly attention (Walk & Andersson, Reference Walk and Andersson2020; Minkowitz et al., Reference Minkowitz, Twumasi, Berrett, Chen and Stewart2020; Kang, Baek, and Kim Reference Kang, Baek and Kim2021).

To consolidate the produced knowledge, it is important to establish a dedicated bibliographic database which can serve as an infrastructure for this research field. CSS not only provides excellent tools for constructing such a database, but also becomes central to studying and facilitating knowledge production (Edelmann et al., Reference Edelmann, Wolff, Montagne and Bail2020, 68). By applying the newest CSS advancements introduced earlier, we created a unique database: the Knowledge Infrastructure of Nonprofit and Philanthropic Studies (KINPS; https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/NYT5X). KINPS aims to be the most comprehensive and timely knowledge base for tracking and facilitating the intellectual growth of our field. In the second section of this article, we use the KINPS to provide concrete examples and annotated code scripts for a state-of-the-art application of CSS methods in our field.

Data Sources of the KINPS

The KINPS currently builds on three primary data sources: (1) Over 67 thousand bibliographical records of nonprofit studies between 1920s and 2018 from Scopus (Ma & Konrath, Reference Ma and Konrath2018); (2) Over 19 thousand English records from the Philanthropic Studies Index maintained by the Philanthropic Studies Library of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis; and (3) Google Scholar, the largest bibliographic database to date (Gusenbauer, Reference Gusenbauer2019; Martín-Martín et al., Reference Martín-Martín, Orduna-Malea, Thelwall and López-Cózar2018).

Database Construction Methods

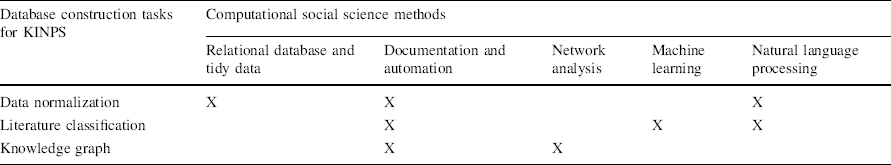

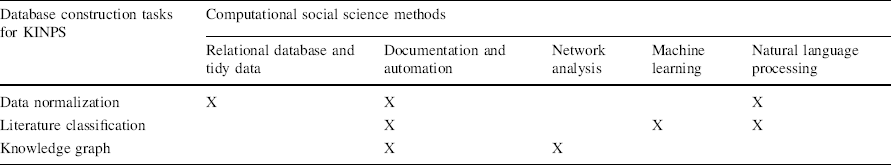

Constructing the database primarily involves three tasks: (1) normalizing and merging heterogeneous data records; (2) establishing a classification of literature; and (3) building a knowledge graph of the literature. As Table 3 presents, each of the three tasks requires the application of various computational methods introduced earlier. We automate the entire workflow so that an update only takes a few weeks at most.Footnote 3

Table 3 Computational social science methods used in constructing the Knowledge Infrastructure of Nonprofit and Philanthropic Studies

Database construction tasks for KINPS |

Computational social science methods |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Relational database and tidy data |

Documentation and automation |

Network analysis |

Machine learning |

Natural language processing |

|

Data normalization |

X |

X |

X |

||

Literature classification |

X |

X |

X |

||

Knowledge graph |

X |

X |

|||

Normalizing Data Structure from Different Sources

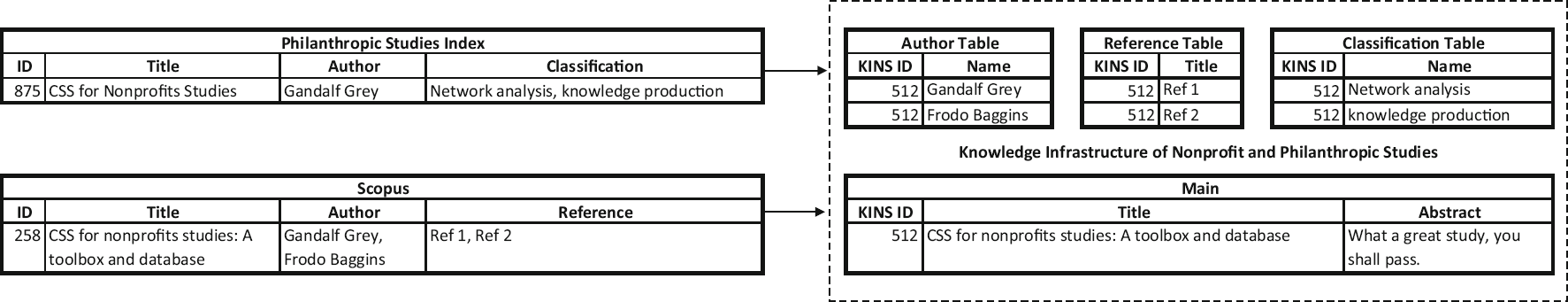

The bibliographic records from different sources are in different formats, so the first task is to normalize these heterogeneous entries using the same database schema and following the principles of relational databases. This task is especially challenging when different data sources record the same article as Fig. 2 illustrates.

Fig. 2 An example of data normalization

To normalize and retain all the information of an article from different sources, the schema of the KINPS should achieve a fair level of “completeness” that can be evaluated from three perspectives: schema, column, and population (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Qun, Chao and Huafang2017). Schema completeness of the KINPS measures the degree to which the database schema can capture as many aspects of an article as possible. As Fig. 2 illustrates, the schema of the KINPS includes both “Reference Table” and “Classification Table.” Column completeness measures the comprehensiveness of attributes for a specific perspective. For example, only the KINPS has the “Abstract” attribute in the “Main” table. Population completeness refers the extent to which we can capture the entire nonprofit literature. It can be evaluated by the process for generating the corpus, which was detailed in Ma and Konrath (Reference Ma and Konrath2018, 1142). Figure 3 shows the latest design of KINPS’s database schema.

Fig. 3 Design of database schema of the Knowledge Infrastructure of Nonprofit and Philanthropic Studies (2020–12-14 update)

Merging Heterogeneous Data Records using NLP Methods

Another challenge is disambiguation, a very common task in merging heterogeneous records. As Fig. 2 shows, records of the same article from different sources may vary slightly. The disambiguation process uses NLP methods to measure the similarity between different text strings.

A given piece of text needs to be preprocessed and represented as numbers using different methods so that they can be calculated by mathematical models (Jurafsky & Martin, Reference Jurafsky and Martin2020, 96). The preprocessing stage usually consists of tokenization (i.e., splitting the text strings into small word tokens) and stop word removal (e.g., taking out “the” and “a”). The current state-of-the-art representation methods render words as vectors in a high dimensional semantic space pre-trained from large corpus (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2019; Mikolov et al., Reference Mikolov, Chen, orrado and Dean2013).

For the disambiguation task, after preprocessing the text strings of publications from different data sources, we converted the text strings to word vectors using the conventional count vector method (Ma, Reference Ma2021, 670) and then measured the similarity between two text strings by calculating the cosine of the angle between the two strings’ word vectors (Jurafsky & Martin, Reference Jurafsky and Martin2020, 105). This process helped us link over 3,100 records from different sources with high confidence (code script available at https://osf.io/pt89w/).

Establishing a Classification of Literature

Classification reflects how social facts are constructed and legitimized from a Durkheimian perspective. A classification of literature presents the anatomy of scholarly activities and also forms the basis for building knowledge paradigms in a discipline or research area (Kuhn, Reference Kuhn1970). What is the structure of knowledge production by nonprofit scholars, how does the territory evolve time, and what are the knowledge paradigms in the field? To answer such fundamental questions, the literature of nonprofit and philanthropy needs to be classified in the first place.

We classified references in the KINPS using state-of-the-art advancements in supervised machine learning and NLP (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2019). After merging data records from different sources, 14,858 records were labeled with themes and included abstract texts. We used the title and abstract texts as input and themes as output to train a ML algorithm. After the classification algorithm (i.e., classifier) was trained and validated, it was used to predict the topics of all 60 thousand unlabeled references in the KINPS (code script available at https://xxx).

The classification in KINPS should be developed and used with extreme prudence because it may influence future research themes in our field. We made a great effort to assure that the classification is relevant, consistent and representative. First, the original classification was created by a professional librarian of nonprofit and philanthropic studiesFootnote 4 between the late 1990s and 2015. Second, we normalized the original classification labels following a set of rules generated by three professors of philanthropic studies and two doctoral research assistants with different cultural and educational backgrounds. Third, we invited a group of nonprofit scholars to revise the predicted results, and their feedback can be used to fine-tune the algorithm. In future use of the database, continuously repeating this step will be necessary to reflect changes in research themes in the field. Lastly, bearing in mind that all analysis methods should be applied appropriately within a theoretical context, if scholars find our classification unsatisfactory, they can follow our code scripts to generate a new one that may better fit their own theoretical framing.

Building a Knowledge Graph of the Literature

From the perspective of disciplinary development, three levels of knowledge paradigm are crucial to understand the maturity of a research field. Concepts and instruments are construct paradigms (e.g., social capital), which are the basis of thematic paradigms Footnote 5 (e.g., using social capital to study civic engagement). By organizing different thematic paradigms together, we are able to analyze the metaparadigms of our knowledge (Bryant, Reference Bryant1975, 356).

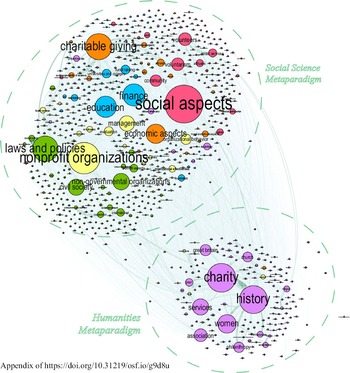

We can use a network graph to analyze the structure and paradigms of the knowledge in our field (Boyack et al., Reference Boyack, Klavans and Börner2005). Figure 4 illustrates the knowledge structure of nonprofit and philanthropic studies based on the KINPS. The online appendix (https://osf.io/vyn6z/) provides the raw file of this figure and more discussion from the perspectives of education, publication, and disciplinary development.

Fig. 4 A visualization of the knowledge structure of nonprofit and philanthropic studies

In this network graph, nodes represent the classifications labels established in the preceding section, two nodes are connected if a reference is labeled with both subjects, and the edge weight indicates the times of connection. The nodes are clustered using an improved method of community detection and visualized using a layout that can better distinguish clusters (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Brown, Klavans and Boyack2011; Traag et al., Reference Traag, Waltman and van Eck2019). Details and source codes are available in the OSF repository (code script available at https://osf.io/tnqkr/).

As Fig. 4 shows, there are two tightly connected metaparadigms in our field: humanities and social science metaparadigms. We encourage readers to discover the key references related to the different paradigms via the KINPS’s online interface. The humanities metaparadigm includes historical studies of charity, women, church, and philanthropy and many other topics. The social science metaparadigm includes five thematic paradigms represented in different colors. For each paradigm, we mention key topics: (1) the sociological paradigm includes the study of local communities and volunteering; (2) the economic paradigm includes research on giving and taxation; (3) the finance paradigm includes research on fundraising, marketing, and education; (4) the management paradigm studies evaluation, organizational behavior, and employees and prefers “nonprofit organizations” in discourse; and (5) the political and policy paradigm includes research on law and social policy, civil society, and social movements and prefers “non-governmental organizations” in discourse. More thematic paradigms can be found by fine-tuning the community detection algorithm (e.g., Heemskerk & Takes, Reference Heemskerk and Takes2016, 97), which will be part of future in-depth analysis of the KINPS.

Overall, the empirical examples here provide us a stimulus for studying the field’s development. Nonprofit scholars have been talking about intellectual cohesion and knowledge paradigms as indicators of this field’s maturity (Young, Reference Young1999, 19; Shier & Handy, Reference Shier and Handy2014; Ma & Konrath, Reference Ma and Konrath2018). Future studies can build on existing literature, the KINPS database, and the computational methods introduced in the proceeding sections to assess the intellectual growth of our field.

Facing the Future of Nonprofit Studies: Promoting Computational Methods in Our Field

We strongly believe that computational social science methods provide a range of opportunities that could revolutionize nonprofit and philanthropic studies. First, CSS methods will contribute to our field through their novel potential in theory building and provide researchers with new methods to answer old research questions. Using computational methods, researchers can generate, explore, and test new ideas at a much larger scale than before. As an example, for the KINPS, we did not formulate a priori expectations or hypotheses on the structure of nonprofit and philanthropic studies. The knowledge graph merely visualizes the connections between knowledge spaces in terms of disciplines and methodologies. As such it is a purely descriptive tool. Now that it is clear how themes are studied in different paradigms and which vocabularies are emic to them, we can start to build mutual understanding and build bridges between disconnected knowledge spaces. Also, we can start to test theories on how knowledge spaces within nonprofit and philanthropic studies develop (Frickel & Gross, Reference Frickel and Gross2005; Shwed & Bearman, Reference Shwed and Bearman2010).

Second, CSS methods combine features of what we think of as “qualitative” and “quantitative” research in studying nonprofits and voluntary actions. A prototypical qualitative study relies on a small number of observations to produce inductive knowledge based on human interpretation, such as interviews with foundation leaders. A prototypical quantitative study relies on a large number of observations to test predictions based on deductive reasoning with statistical analysis of numerical data, such as scores on items in questionnaires completed by volunteers. A prototypical CSS study can utilize a large number of observations to produce both inductive and deductive knowledge. For example, computational methods like machine learning can help researchers inductively find clusters, topics or classes in the data (Molina & Garip, Reference Molina and Garip2019), similar to the way qualitative research identifies patterns in textual data from interviews. These classifications can then be used in statistical analyses that may involve hypothesis testing as in quantitative research. With automated sentiment analysis in NLP, it becomes feasible to quantify emotions, ideologies, and writing style in text data, such as nonprofits’ work reports and mission statements (Farrell, Reference Farrell2019; J. D. Lecy et al., Reference Lecy, Ashley and Santamarina2019). Computational social science methods can also be used to analyze audiovisual content, such as pictures and videos. For example, CSS methods will allow to study the use of pictures and videos as fundraising materials and assess how these materials are correlated with donation.

Third, a promising strength of CSS methods is the practice of open science, including high standards for reproducibility.Footnote 6 Public sharing of data and source code not only provides a citation advantage (Colavizza et al., Reference Colavizza, Hrynaszkiewicz, Staden, Whitaker and McGillivray2020), but also advances shared tools and datasets in our field. For instance, Lecy and Thornton (Reference Lecy and Thornton2016) developed and shared an algorithm linking federal award records to recipient financial data from Form 990 s. Across our field, there is an increasing demand for data transparency. To illustrate the typical open science CSS approach, with the current article, we not only provide access to the KINPS database, but also annotated source codes for reproducing, reusing, and educational purposes.

Implementing CSS also raises concerns and risks. Like all research and analytical methods, CSS methods are not definitive answers but means to answers. There are ample examples of unintended design flaws in CSS that can lead to serious biases in outcomes for certain populations. ML algorithms for instance can reproduce biases hidden in training dataset, and then amplify these biases while applying the trained algorithms at scale. In addition, researchers may perceive CSS to be the panacea of social science research. The ability to analyze previously inaccessible and seemingly unlimited data can lead to unrealistic expectations in research projects. Established criteria that researchers have used for decades to determine the importance of results will need to be reconsidered, because even extremely small coefficients that are substantively negligible show up as statistically significant in CSS analyses. Furthermore, “big data” often suffer from the same validity and reliability issues as other secondary data—they were never collected to answer the research questions, researchers have no or limited control over the constructs, and in particular, the platform that collects the data may not generate a representative sample of the population (D. M. J. Lazer et al., Reference Lazer, Pentland, Watts, Aral, Athey, Contractor and Freelon2020, 1061). A final concern is with the mindless application of CSS methods as we have already discussed in machine learning section. Even highly accurate predictive models do not necessarily provide useful explanations (Hofman et al., Reference Hofman, Watts, Athey, Garip, Griffiths, Kleinberg and Margetts2021). Research design courses within the context of CSS methods are highly desirable. Students must learn how to integrate computational methods into their research design, what types of questions can be answered, and what are the concerns and risks that can undermine research validity.

For future research implementing CSS in nonprofit and philanthropic studies and with a larger community of international scholars, we will be working to expand the KINPS to include academic publications in additional languages, starting with Chinese. We encourage interested scholars to contact us to explore options for collaboration. Furthermore, the KINPS is an ideal starting point for meta-science in our field. For example, with linked citation data, it is possible to conduct network analyses of publications, estimating not only which publications have been highly influential, but also which publications connect different subfields of research. Furthermore, by extracting results of statistical tests, it is possible to quantify the quality of research—at least in a statistical sense—through the lack of errors in statistical tests, and the distribution of p values indicating p-hacking and publication bias. In future, algorithms may be developed to automatically extract effect sizes for statistical meta-analyses. We highly encourage scholars to use KINPS and advance nonprofit and philanthropic studies toward a mature interdisciplinary field and a place of joy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Revolutionizing Philanthropy Research Consortium for suggestions on keywords, Sasha Zarins for organizing the Consortium, and Gary King for commenting on interdisciplinary collaboration. We appreciate the constructive comments from Mirae Kim, Paloma Raggo, and the anonymous reviewers, and thank Taco Brandsen and Susan Appe for handling the manuscript. The development of KINPS uses the Chameleon testbed supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Author contributions

J.M. drafted the manuscript; designed definitions, selected the methods to be discussed in the toolbox section, constructed the database and online user interface. I.A.E. drafted the technical details. A.D.W. collected example studies and drafted the review sections. M.X. and Y.Y. collected partial data for training the machine learning algorithm. R.B. and P.W. helped frame the manuscript and definitions, and drafted the concluding sections. J.M., A.D.W, R.B., and P.W. finalized the manuscript.

Funding

J.M. was supported in part by the 2019–20 PRI Award and Stephen H. Spurr Centennial Fellowship from the LBJ School of Public Affairs and the Academic Development Funds from the RGK Center. P.W.’s work at the IU Lilly Family School of Philanthropy is funded through a donation by the Stead Family; her work at the VU University Amsterdam is funded by the Dutch Charity Lotteries.