The cost of ruling – the fact that incumbents lose support at the next election – is one of the few empirical laws of political science (Cuzan, Reference Cuzan2015), documented in a number of studies (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad and Paldam1999; Narud & Valen, Reference Narud, Valen, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Paldam, Reference Paldam1986; Stevenson, Reference Stevenson2002; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017).Footnote 1 A recent study estimates that governments on average lose two to three percentage points of their support at each election (Cuzan, Reference Cuzán2022), a loss that is close to or larger than the plurality margin in most recent European elections (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2021, p. 82). The cost of ruling thus underlies alternation in office, which is a key mechanism of democratic representation, ensuring that executive power rests with different segments of the electorate and that changing public preferences are reflected in government policies (Budge, Reference Budge2019, p. 191).

Given the substantial importance of the cost of ruling, it is striking how little effort political science has put into understanding the mechanisms behind it (cf. Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019; Thesen et al., Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2020). Several theoretical mechanisms were suggested more than 20 years ago (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad and Paldam1999), most of which received little empirical support in later studies (for a review, see Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017). Consequently, the mechanisms underlying this important empirical law are still poorly understood. This paper focuses on media coverage as a key driver of the almost universally observed cost of ruling phenomenon. We concentrate on the information available to voters about politics and political actors, bringing insights from the literature on media and politics into the study of governing costs.

In political communication, it is well established that incumbents get more media attention than the opposition, a phenomenon that is usually referred to as the incumbency bonus (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, van Aelst and Legnante2012). We argue that this bonus in the quantity of coverage hides a burden of bad news. Negativity is a central news value (Harcup & O'Neill, Reference Harcup and O'Neill2017), which is reflected in a tendency to report on political and societal problems and the well‐known negativity bias of the media (Soroka, Reference Soroka2014, pp. 72–94). However, news negativity is not evenly distributed. Critical and negative news frames are linked to responsibility, and those in power are more often relevant sources or objects of reporting when problems are addressed, and blame is attributed in the news (Green‐Pedersen et al., Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and Thesen2017). The result is an incumbency burden in political communication; news content featuring incumbents is more negative than news where the opposition appears.

Prior research on framing, agenda setting and priming (e.g., Druckman et al., Reference Druckman, Hennessy, St Charles and Webber2010; Matthews, Reference Matthews2019; Valenzuela, Reference Valenzuela2019) suggests that this bias could have consequences. As argued by Iyengar and Kinder (Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987, p. 63): ‘By calling attention to some matters while ignoring others, [television] news influences the standards by which governments, presidents, politics, and candidates for public office are judged’. In other words, because of the incumbency burden governments are systematically judged more often in light of negativity than their competitors. The outcome, we contend, is a gradual decline of voter support for incumbents. Finally, we argue that the distribution of policy responsibility moderates the negative effect of bad news on government support, because it influences the ease with which voters are able to link the incumbency burden and the incumbent parties. Thus, the argument put forward in this paper offers an explanation of both constant and variable aspects of the cost of ruling phenomenon.

Since we study the information available to voters through the news, it is important to address our assumptions regarding the role of news media and the real‐world problems they report on. On the one hand, we expect that the tone of news coverage, and thus also the incumbency burden, is related to objective societal problems, whether it is unemployment and economic conditions, environmental challenges, or crime etc. At the same time, work on journalistic framing demonstrates that ‘journalists are framers’ (Baden, Reference Baden, Wahl‐Jorgensen and Hanitzsch2019, p. 229). But they do not frame at random. They work in news institutions governed by a set of norms and rules for what news is (Cook, Reference Cook1998), that shapes journalistic decisions about which actors to cover and how to cover them. The incumbency burden in the news inevitably reflects both these norms and rules, and the economic and social realities that incumbents face. We demonstrate this in a separate analysis of economic news, showing that the incumbency burden is higher during economic downturns but still always a feature of political news that systematically disfavors incumbents.

Empirically we draw on a new and extensive dataset on mass media coverage of politics in 12 different newspapers from 2000–2018 in four countries: the United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands. This dataset allows us to trace the amount and tone of news media attention to all cabinets and their respective opposition in the countries and period we study, based on the appearance of these actors across approximately 770,000 news articles. The daily news coverage of incumbents and opposition is then aggregated and linked to monthly opinion poll data. Analyzing the data, three results regarding the content and effect of political news stand out. First, media coverage involving incumbents is systematically and cross‐nationally more negative than coverage involving the opposition, which supports our key notion that the incumbency bonus is in fact better understood as an incumbency burden. Incumbents do have a surplus of media appearances compared to the opposition, but they tend to appear more often in a context of negative news. The incumbency burden, however, is not constant, but varies over time and across political systems, making it possible to assess its impact on government support. This leads to the second major finding of this paper: the higher the incumbency burden in news coverage, the more the incumbents are punished in the opinion polls. Thus, the incumbency burden is an important predictor of incumbent support – and given that this burden is present in 80 per cent of the period we cover, it also offers an explanation of the gradual and nearly constant vote loss that characterizes the cost of ruling. Third, the burden effect on incumbent support is moderated by concentration of policy responsibility. Utilizing the comparative variation in our data, the analysis shows that shared government responsibility offers a shield against parts of the negative electoral effects of the news coverage that governments inevitably will experience. In combination, our theoretical argument and empirical findings accentuate the importance of the interplay between critical journalism on the one hand, and the political context on the other, in understanding the cost of ruling.

From incumbency bonus to incumbency burden

Holding a government office implies control over the bureaucracy and the legislative process, and easy access to media attention. Thus, there are good reasons why incumbency could be the source of an electoral advantage. This, however, is not the empirical reality. Yet, empirically corroborated explanations of governing costs have been in short supply. Among the explanations of why incumbents (nearly) always lose support, three theories have received most attention (cf. Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad and Paldam1999). First, the coalition of minorities theory argues that incumbent parties have over‐promised to win government power. As time in office goes by, more and more groups are disappointed, and as these groups vary across policy promises, a growing coalition of disappointed minorities causes declining support for the government. Second, the median‐gap theory argues that the cost of ruling emerges because incumbent parties have moved closer to the median voter to win office. However, the longer a government stays in office, the more it moves towards its ideal position and away from the median voter. This results in a policy misrepresentation that pushes median voters to support the opposition instead. Finally, the grievance asymmetry theory argues that voters overemphasize negative changes and blame them on the government, especially in terms of the economy. However, with the exception of policy misrepresentation, these theories have found little empirical support in later studies (Thesen et al., Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2020; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017).

More recent studies of the cost of ruling have focused on the dynamics of coalition cabinets, emphasizing that governing costs relate to the distribution of policy responsibility between junior and larger members in coalition governments (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019; Hjermitslev, Reference Hjermitslev2020; Klüver & Spoon, Reference Klüver and Spoon2020). These studies address important gaps in our theoretical and empirical understanding of how cooperation and compromise between governing parties affect incumbent support. While we draw on some of these insights, our focus remains on the cabinet level in order to understand why there is a cost in the first place, leaving questions about the distribution of costs across coalition partners for future studies.

Following Thesen et al. (Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2020), we propose a general account of the mechanism underlying the cost of ruling, using information and news coverage of politics as our starting point. Within the literature on political communication, the so‐called incumbency bonus is a well‐established empirical finding (De Swert, Reference De Swert2011; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, van Aelst and Legnante2012). Governing parties or incumbents get more media attention than the opposition, a fact that testifies to the importance of the news values of power and relevance (Harcup & O'Neill, Reference Harcup and O'Neill2017). The term ‘bonus’ indicates that this is perceived as an advantage for governing parties, and that such a disparity in news access reflects – and possibly strengthens – the existing distribution of power between political actors. However, there are two important gaps in this interpretation. First, it establishes a link between news values and the quantity of media coverage without considering the quality of media coverage (Green‐Pedersen et al., Reference Green‐Pedersen, Mortensen and Thesen2017). This limits our understanding of incumbents’ news dominance to a matter of salience or agenda setting, when it should of course also be studied from the perspectives of ‘second level agenda setting’ or framing (Valenzuela, Reference Valenzuela2019). Incumbents dominate the news, but whether or not this is in fact a bonus will depend on the type of frames that news with incumbents typically contain. Second, the ‘bonus interpretation’ does not address how different news values, such as power and negativity, are likely to be correlated. Standard news criteria lead journalists to concentrate on negative developments and societal problems (Harcup & O'Neill, Reference Harcup and O'Neill2017), and at the same time also to cover the actors that can be deemed responsible (Soroka, Reference Soroka2006).

The news focuses on incumbents because they are powerful, but with great power comes great responsibility. Due to their responsibility, government parties and ministers will often be accompanied by problems when they figure in the news. This does not mean that incumbents will only appear in news based on critical watchdog journalism, nor does it preclude that governments can sometimes increase their dominance in the news in relation to crises without suffering electorally (e.g., a rally‐round‐the‐flag context during wars or the pandemic; Johannson et al., Reference Johansson, Hopmann and Shehata2021). Yet, the argument about the incumbency burden holds that incumbents in the long run are more likely to appear in bad news as compared to the opposition.

As suggested in the introduction, our argument assumes that political news does not present a 1:1 reflection of societal problems, and of what incumbents do to handle them. Studies of particular policy areas like economy (Soroka, Reference Soroka2006) and crime (Soroka, Reference Soroka2014, pp. 72–82), for which relative objective measures of societal problems exist, have documented the negativity bias of news coverage. Furthermore, studies of pledges find that although most pledges are kept (Thomson et al., Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser‐Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), media focus substantially more on broken promises than on those that are fulfilled (Müller, Reference Müller2020; Duval, Reference Duval2019). This does not imply that news is in‐varyingly negative, no matter for instance the development of the state of the economy. News negativity will vary, reflecting among other factors the ups and downs of economic realities. And at a more structural level, the degree of critical focus on the incumbent may vary according to the ideological orientation of the news outlet and its audience, as well as the cross‐national variation in professionalization and commercialization that exists between different media systems (Hallin & Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004).

The incumbency burden will in other words vary in strength, depending on factors like the economic and institutional context. But the incumbency burden is the product of entrenched news values that constantly draw attention to problems, and to the political actors that hold office and policy responsibility. The tone of critical, political news will therefore in the long run disfavor incumbents, even when the economic context or other conditions are favorable. The quantitative overweight of incumbent news thus provides no advantage in party competition because it is accompanied by a bias towards bad news, summarized in our first expectation about the incumbency burden:

H1: Incumbents appear in news that is more negative compared to the news in which the opposition figures.

The next step in our argument is that this imbalance in the tone of news content propagates to the electoral competition between incumbents and the opposition. We know from numerous agenda setting studies that salience in the news is transferred to the public agenda (Valenzuela, Reference Valenzuela2019). If H1 is true, and voters are constantly exposed to an incumbency burden, this will also mean that their evaluations of political actors are made in context of information that systematically disfavors incumbents. Research on priming and related mechanisms, explored in a long line of studies of the relationship between media coverage and vote choice (Aaldering et al., Reference Aaldering, Van der Meer and Van der Brug2018; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, Vliegenthart, De Vreese and Albæk2010; Iyengar & Kinder, Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987; Kleinnijenhuis et al., Reference Kleinnijenhuis, Van Hoof, Oegema and De Ridder2007; Matthews, Reference Matthews2019; Van Spanje & Azrout, Reference Van Spanje and Azrout2019), suggests that this news imbalance will have consequences for government support. More precisely, the incumbency burden in the media (H1) converts to an electoral burden in the sense that it affects voter support negatively, as expressed in hypothesis 2a:

H2a: The incumbency burden affects incumbent support negatively.

The electoral consequence of the incumbency burden can materialize in different ways. It can show up as a short‐term and negative effect on government support, reflecting the public's immediate response to the day‐to‐day incumbency burden. This is the assumption behind hypothesis H2a above, which represents a straightforward application of the burden effect within a media priming approach. However, it may also show up as a long‐term effect that gradually undermines support for the incumbent government due to the accumulation of negative media attention over the course of its tenure (Green & Jennings, Reference Green and Jennings2016; Thesen et al., Reference Thesen, Mortensen and Green‐Pedersen2020). Supplementing the immediate negative impact of the incumbency burden, the assumption here is that governments can hardly reset their public image from one month to the next. Given what we know about negativity and retrospective voting (Healy & Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013; Soroka, Reference Soroka2014), we find it more likely that the disadvantages that incumbents face in terms of news attention are stored in public memory. Consequently, the accumulated burden should become relevant to incumbent support, an expectation which is summarized in the following hypothesis:

H2b: The accumulated incumbency burden affects incumbent support negatively.

Finally, time is relevant not only because the incumbency burden accumulates during a government's tenure. As implied in both the coalition of minorities and median gap or policy misrepresentation theories, governments could become more vulnerable to vote loss over time: as more policies are enacted, the number of disappointed voters grows and the gap between the median voter preference and the policy status quo increases (Nannestad & Paldam, Reference Nannestad and Paldam1999; Wlezien, Reference Wlezien2017). Consequently, the day‐to‐day incumbency burden is likely to inflict more serious electoral damage the longer a government has been in office. This is the third way in which we expect the negative electoral consequence of the incumbency burden to materialize, summarized below in hypothesis 2c:

H2c: The incumbency burden affects incumbent support more negatively with increasing tenure.

All three mechanisms behind the three hypotheses (H2a, b and c) are consistent with the cost of ruling phenomenon. The three hypotheses also represent the implications of our argument in its most general form, linking news content to incumbent support through our concept of an incumbency burden. As explained above, this burden is closely related to the policy responsibility of incumbent governments. However, the extent to which incumbents have concentrated power – and thus concentrated responsibility –varies. Studies on governing costs across political systems have highlighted how the incumbency disadvantage varies according to the concentration and visibility of policy responsibility (Palmer & Whitten, Reference Palmer, Whitten, Dorussen and Taylor2002; Rose & Mackie, Reference Rose, Mackie, Daalder and Mair1983; Strøm, Reference Strøm1990). Where concentration and visibility are high, voters can assign blame to the government more easily, while government will find it more difficult to pursue and succeed with various blame‐shifting and blame‐avoidance strategies. It is a reasonable extension of this argument to expect that negative media attention will hurt incumbents more easily when responsibility is concentrated, for instance in the context of single‐party cabinets. This moderating effect is summarized in hypothesis 3:

H3: The burden effect on incumbent support is conditioned by the concentration of policy responsibility. When responsibility is highly concentrated, the negative burden effect increases.

Data, design and methods

Examining the hypotheses derived above requires a dataset of news, cabinets and contexts that captures variation on the many dimensions that we are interested in. Our investigation builds on two main datasets covering regular observations on government support and news content. The first is collected and made available by Jennings and Wlezien (Reference Jennings and Wlezien2016) and contains data from thousands of vote intention polls across close to 30 countries since 1942. Our dependent variable of incumbent support was measured using this dataset (see more below). The second dataset is much more limited in scope with regards to countries and years, but provides a unique, extensive daily coverage of key news sources in four European countries – the United Kingdom, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands – from 2000−2018. In order to maximize variation and coverage, we include all months and countries for which we have data from both these datasets. Consequently, it is the resource intensive and demanding collection and coding of news data that restricts our sample of cases and period.Footnote 2

Studying the United Kingdom, Norway, Denmark and the Netherlands allows us to analyze developments that have taken place across different settings, both in terms of political systems and media systems. With regard to the former, our cases cover variations in electoral and party systems. We follow three proportional and one majoritarian system. The group of proportional systems varies with respect to electoral proportionality, party system size, polarization, structure of party competition and government formation (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart2012; Mair, Reference Mair, Katz and Crotty2006).Footnote 3 In terms of media systems, applying the categorization of Hallin and Mancini (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004), the liberal media system of the United Kingdom is characterized by a higher level of commercialization, journalistic professionalism and polarization compared to the democratic corporatist model of the other three countries. Based on the characteristics of our country sample, we believe our conclusions likely travel reasonably well to similar countries of Northern Europe and the North Atlantic (e.g. Finland, Sweden, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Ireland). However, the news corpus on which we base this study did not include a country from what Hallin and Mancini describe as the ‘polarized, pluralist model’, which suggests that generalizations to Southern Europe would be highly tentative.

Our two key variables on political communication biases – the incumbency bonus and the incumbency burden – are measured using the dataset of daily news media content from 2000−2018. This corpus contains 5.8 million newspaper articles from a total of 12 newspapers across the four countries. The selection of newspapers aims for comparability across countries and is based on the approach in a recent comparative study on political journalism (De Vreese et al., Reference De Vreese, Esser and Hopmann2017). For each of the four countries, the sample includes the leading left‐leaning broadsheet, the leading right‐leaning broadsheet and one mass‐market newspaper.Footnote 4 This selection of news sources thus allows us to examine the general nature of the incumbency burden across outlets with different ideological orientation and different styles of journalism; factors that as discussed above are likely to affect how news outlets approach the incumbent.

A high‐choice media environment has of course put established news media under pressure, raising the question if newspapers are still a good indicator of the media environment. Nevertheless, research shows that traditional media still play a dominant role in agenda‐setting and the media landscape (Djerf‐Pierre & Shehata, Reference Djerf‐Pierre and Shehata2017; Harder et al., Reference Harder, Sevenans and Van Aelst2017; Su & Xiao, Reference Su and Xiao2021; Langer & Gruber, Reference Langer and Gruber2021). Even if citizens to an increasing extent encounter news through social media, the news are still produced by legacy news media operating under the journalistic criteria that we discussed before. This supports the assumption that our news corpus is a valid proxy for the information available to the public via the media. The selection of news sources and the construction of the news corpus are further explained in the Supporting Information (see Appendix A).

Before turning to the measurement of the incumbency bonus and burden, we must clarify what constitutes a change of government in this study. In line with our focus on the electoral impact of political news content, it is important to use those changes in office that are likely to be perceived as de facto cabinet changes by the public. We therefore define alternations in office based on two criteria. The first is based on whether a new party takes over the prime minister's (PM) post. In other words, a cabinet that is re‐elected does not count as a new cabinet, and neither does a cabinet with a new PM from the same party. The second criterion rests on substantial changes in cabinet composition for cabinets with the same PM party. More concretely, we count it as a cabinet shift when an existing cabinet with the same PM changes its composition to, or from, a single‐party cabinet. In other words, when a three‐party cabinet loses (or gains) one coalition partner this is not counted as a new cabinet. But when the Liberal PM Lars Løkke Rasmussen expanded his single‐party cabinet with two additional parties in 2016, and the Lib‐Con coalition was replaced by the single‐party cabinet of Cameron in 2015, this is counted as a cabinet shift.

Measuring the incumbency bonus and the incumbency burden

The news appearances of incumbents and the opposition are captured by running a high number of queries in the corpus, in order to identify both mentions of parties (full name and abbreviation) as well as mentions of individual politicians serving as either members of parliament, ministers or party leaders for incumbent and opposition parties respectively. More details about the queries are presented in Supporting Information Appendix A. Based on the result of these queries, the number of articles in which any incumbents (the opposition) appear are summed across months. This produces a simple and straightforward measure of monthly news visibility for both incumbents and the opposition. The distribution of news attention between incumbents and the opposition – the incumbency bonus – is then estimated by subtracting the number of news articles in which opposition actors appear from the corresponding count for government actors.Footnote 5 A higher bonus thus indicates a stronger news dominance of incumbents.

We conceive of the imbalance or bias in political news as relating to the tone or sentiment in its content. Note again that the idea about an incumbency burden stretches beyond news evaluation of government and opposition. The concept builds on how news invariably focuses on problems and those who hold policy responsibility, and thus encompasses news which presents negative information without necessarily blaming or evaluating governments. In other words, the incumbency burden means that news where incumbents are present is expected to be more negative. As with the measurement of the bonus, the volume of our collected data means that we need assistance from computers in order to successfully proxy the tone of political news. Recent studies in political communication and political science (Rheault & Cochrane, Reference Rheault and Cochrane2020; Rudkowsky et al., Reference Rudkowsky, Haselmayer, Wastian, Jenny, Emrich and Sedlmair2018) have shown the potential of using word embedding models. Our approach to measuring news sentiment is similar, relying on a method proposed by Rheault et al. (Reference Rheault, Beelen, Cochrane and Hirst2016) and further developed by de Vries (Reference De Vries2022). The method allows us to calculate how positive or negative each sentence in our corpus is. The performance of the sentiment coding was validated against human coding, producing F1‐scores in the range of 0.61–0.64 (see Supporting Information Appendix A for more details).

Based on this approach, the incumbency burden is calculated by subtracting the mean tone of sentences in which opposition actors appear from the corresponding mean tone of sentences in which government actors appear. A higher burden thus reflects a stronger news tone bias in disfavor of incumbents. This is arguably a simple measure which does not distinguish between negative news evaluations of political actors and negative news containing political actors. It nevertheless allows us to tap into the key component of the argument about an incumbency burden: government actors tend to appear more in a context of negative news than opposition actors. Note that since we measure the sentiment of sentences, we can identify variations in news tone on a sub‐article level. This means that even though a lot of articles contain both opposition and government actors, we are still able to proxy the tone of the content in which the respective actors appear within these articles. Finally, the cumulated incumbency burden simply cumulates the burden measure for each month the incumbent is in office.

Measuring incumbent support

The dependent variable when analyzing the incumbency burden and the cost of ruling is incumbent support. We measure this using an extract of the Jennings and Wlezien vote‐intention dataset which covers the ‘best estimates’ of party preferences from several survey houses at each point in time (for detailed documentation, see Appendix S1 of Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2016). Monthly support for cabinet parties was first averaged across all polls in a given month, and then aggregated across all cabinet parties, corresponding to the burden measure which aggregates tone in news content across all incumbent (and opposition) parties. The result is the dependent variable of monthly incumbent support (in per cent). The choice of using poll data instead of election results is based on the assumption that the electorate's party preferences are subject to an ongoing process of updating in the period between elections (Jennings & Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2016). Although the cost of ruling can only be observed in elections, the mechanisms by which governments lose supporters are not restricted to Election Day or campaigns. If we want to advance our understanding of governing costs, we therefore need to also study the continuous development in government vote intention.

Moderators and control variables

The combination of news and vote‐intention data has been supplemented by a number of moderators and control variables. Based on the extensive literature on the economic vote (Dassonneville & Lewis‐Beck, Reference Dassonneville and Lewis‐Beck2019), any modelling of governing costs should take into account the economic context. We do this via two variables. The OECD's composite leading indicator (CLI) provides a measure of economic activity built on a wide range of key short‐term economic indicators, while monthly unemployment rates are taken from the OECD's internationally comparable employment statistics.Footnote 6 Though, these measures do not capture all aspects of the economy, they – taken together – provide a quite broad picture of the state of the economy.

Both unemployment and economic activity serve as control variables in the main analyses below. However, they also play an important role in additional analyses of economic news. A potential objection to our argument could be that news simply mediates the state of the world. Any negative effect of the incumbency burden on incumbent support would in this perspective be spurious and would disappear once the state of the world is controlled for. In the theory section, we have argued that such an interpretation of the relationship between objective real‐world conditions and news coverage runs counter to existing research. Still, we attempt to address this objection better empirically by presenting additional analyses on a sub‐sample of the news data. While it is of course impossible to measure the ‘state of the world’, the idea is simply that when we restrict our sample to economic news, the (economic) incumbency burden could be expected to follow the development of the economic variables more closely. Consequently, inspired by Soroka (Reference Soroka2006), we explore the relationship between the state of the economy and the incumbency burden in economic news in order to examine if the burden is just a simple reflection of economic realities.

Since the incumbency bonus only captures the gap between government and opposition news appearances, the models also include the total number of news appearances by all political parties to control for the saliency of political news. The tenure variable counts the number of months in office for each respective cabinet, and is used to evaluate the extent to which our approach contributes towards explaining the cost of ruling. Additionally, three cabinet‐level characteristics available from the ParlGov‐database (Döring & Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2021) are added to the models reported below.Footnote 7 First, the two most important properties of cabinets – size and parliamentary strength – are proxied through the number of cabinet parties Footnote 8 and the cabinet seat share (in parliament), of which the former is used for testing H3 about concentration of policy responsibility and variations in the burden effect. Finally, in line with recent research indicating that the degree of cabinet compromise affects the cost of ruling (Fortunato, Reference Fortunato2019), we also control for the left‐right distance between coalition partners.Footnote 9

Empirical evaluation of Hypothesis 1

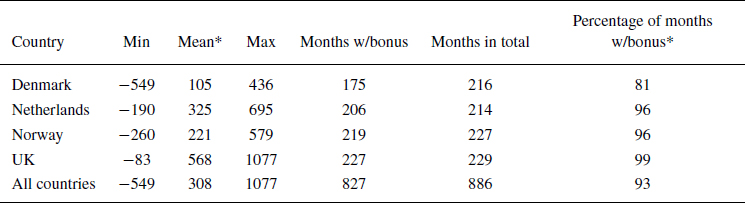

Table 1 summarizes descriptive statistics for our measure of the incumbency bonus. Recall that in line with a consistent finding in political communication research, we expect that incumbents in general, across time and political systems, dominate the news compared to representatives from opposition parties. The pattern in Table 1 corroborates this expectation. Across our four countries and time periods, we have a total of 886 monthly observations on the aggregated news tone imbalance. In this material, incumbents outnumber non‐incumbents in 827 months. An incumbency bonus is consequently observed in 93 per cent of the country–months covered in our data. On average, incumbents appear in 308 more articles than the opposition per month.

Table 1. Descriptives for the incumbency bonus

*All means are significantly (p < 0.05) above zero, and all percentages have confidence intervals (95 per cent) that do not include 50 per cent.

Disaggregating to the country level, Table 1 also displays some variation across countries. Denmark stands out with a lower incumbency bonus than the other three countries, most likely reflecting the higher prevalence of minority governments. Yet the mean for Denmark still shows a clear incumbency bonus in that incumbents on average outnumber non‐incumbents by 105 news articles per month. The number of months with an incumbency bonus is also lower in Denmark, 81 per cent, compared to the 96–99 per cent range found in the other three countries. Based on Table 1, we find the strongest incumbency bonus in the United Kingdom.

The main argument in this paper is that incumbents’ quantitative news domination reflects a liability, and not a bonus. The reason is that incumbents, compared to opposition parties without government responsibility, appear more often in news that is negative (H1). This incumbency burden in turn results in decreased electoral support for governments. Table 2 sheds light on the first part of this argument. Recapitulating the essence of our operationalization, a negative value equals an absence of the incumbency burden while a positive value indicates its presence. Higher positive values mean a heavier burden in the sense that the news tone gap disfavoring incumbents is larger.

Table 2. Descriptives for the incumbency burden (H1)

*All means are significantly (p < 0.05) above zero, and all percentages have confidence intervals (95 per cent) that do not include 50 per cent.

Across all four countries, incumbents on average appear in news that is more negative than the news in which non‐incumbents are present. As is evident in the bottom row of the table, the measure varies between approximately −0.08 and 0.15 (SD = 0.037). Table 2 also shows that in four out of 5 months (79 percent), incumbents do experience a burden. In three of the four countries (the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Norway) the incumbency burden is even stronger. Again, Denmark stands out with the lowest incumbency burden, but even here incumbents are more likely to appear in news with a more negative tone than the news in which the opposition appears. Thus, Table 2 provides empirical support for hypothesis 1, establishing the incumbency burden as a general political imbalance in news media coverage.Footnote 10

It is also worth considering that the opposition will typically be critical and willing to attack incumbents. Yet, the tone of coverage when incumbents are present in the news is still more negative than when the opposition is present. This means that the negativity of incumbent news media coverage is more than a reflection of the fight between government and a critical opposition, indicating the important role played by news criteria and journalistic norms that systematically disfavor incumbents.

Before analyzing how the incumbency burden relates to incumbent support, we first address the potential concern that such a measure only captures real world developments. In order to do that, we sample economic newsFootnote 11 and explore the association between key economic indicators and the incumbency burden in the news. Using this sub‐sample of our data, Table 3 shows that the incumbency burden in economic news is at its height during periods of rising unemployment or negative economic growth.Footnote 12 However, two other patterns in Table 3 deserve attention. First, the incumbency burden is always present, also when unemployment decreases and when the economy grows. Second, the burden varies considerably, regardless of the state of the economy. Although there are unobserved aspects of economic context that we do not control for (e.g., taxes and inflation), economic growth and unemployment are arguably decisive for the valence of economic news. With previous findings on negativity biases in news coverage of the economy (Soroka, Reference Soroka2006) in mind, the patterns we find support the notion that the incumbency burden – and its effect on incumbent support found in the analyses below – should be interpreted as more than a mere mediation of economic and societal realities.

Table 3. The incumbency burden in economic news, by economic development.

*All means are significantly (p < 0.05) above zero, and all percentages have confidence intervals (95 %) that do not include 50 per cent.

Empirical evaluation of Hypotheses 2 and 3

To assess the impact of the incumbency burden on incumbent support, and subsequently the moderators of this effect, we estimate cross section and panel data regression models. The panels in our case are the 15 cabinets that we follow over the course of their tenure (mean tenure of 48 months). To strengthen causal inference, we control for time‐invariant cabinet heterogeneity by incorporating unit fixed effects. This specification of the panel model removes unobserved constant differences between our cabinets as a potential explanation of their support (Wooldridge, Reference Wooldridge2010).

A fixed effects specification is not ideal if researchers are interested in the influence of constant (or slow moving) factors. But since our main goal is to estimate the effect of time variant factors, more specifically the incumbency burden in the news, including unit fixed effects is preferable. Note however that this is not the case when testing H3 about the differential impact of the burden across cabinets of different size. Since this a property of cabinets that mostly does not change in our sample, H3 is tested using a random effects specification.

Repeated measurement of the same units means that panel data is often characterized by temporal dependence. Adding a lagged dependent variable (LDV) has become the dominant solution to ensure robust estimation in the face of autocorrelation (Keele & Kelly, Reference Keele and Kelly2006). Dafoe (Reference Dafoe2018) demonstrates that conditioning on LDVs is appropriate under the assumption that there is no unobserved persistent causes of the outcome. In this perspective, an LDV model is a relevant choice since a fixed effects model controls for all unobserved heterogeneity that is constant over time.Footnote 13 Finally, we apply a so‐called autoregressive distributed lag model (ADL) with a lagged dependent variable on the right‐hand side of the equation because it supports substantive, theoretical considerations (Keele & Kelly, Reference Keele and Kelly2006, p. 189). First, it allows us to estimate how incumbent support at time t is the function of new information (in the shape of the incumbency burden) that was not available at time t−1. Second, it is likely that the burden effect will be distributed over future time periods, given that various groups of voters will respond at different paces.

Tests find that the panel model with LDV still has autocorrelation and we therefore report estimates with cabinet clustered standard errors. Testing various standard errors in the face of autocorrelation, Hoechle (Reference Hoechle2007, p. 29) concludes that this is the preferred solution for panel data when residuals are believed to be spatially uncorrelated. This is arguably the case for our dataset, where each panel consists of a single cabinet that served in either a different country or at a different point in time than the other cabinets. Due to the many pitfalls when specifying models with time‐series cross‐section data, we report results of several alternative specifications in the Supporting Information Appendix and the robustness section further below.Footnote 14

The coefficient plot in Figure 1 presents the analysis reported in Model 1, Table B1 in the Supporting Information Appendix. The dependent variable is monthly support in the polls (percent) for incumbent parties, and the two main explanatory variables are the incumbency burden (H2a) and the cumulated incumbency burden (H2b).

Figure 1. Coefficient plot, based on regression of incumbent support, Model 1, Table B1 in the Supporting Information Appendix. 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals.

The results in the coefficient plot suggest both an immediate and an accumulated effect of the incumbency burden on government voter support. To ease the interpretation, we have standardized the burden variables prior to estimating the regressions. Consequently, the coefficients show that a one standard deviation increase in the burden diminishes government support by 0.43 (burden) and 0.62 (cumulated burden) percentage points, respectively.Footnote 15 This is a substantial impact, which is especially noteworthy when taking into account that the model includes key factors shown to affect government support in previous research. In particular, we control for economic context and find that unemployment and economic activity influence the cost of ruling in line with expectations, although only the former effect qualifies as statistically significant. The results allow us to discern a negative electoral effect of the incumbency burden from the impact of economic conditions, suggesting that news content exerts an effect on governing costs that is independent from a dominant explanation of aggregate election results.

The cost of ruling basically means that incumbents lose support as a function of time: Their level of support in the next election will be lower than what it was prior to taking office. In modelling terms, one way in which this could manifest itself is through a negative effect of tenure on incumbent support. Furthermore, models of incumbent support that reduce such a negative tenure effect arguably represent a step towards solving the puzzle of why governments ‘always’ lose. Consistent with this perspective, Table B2 in the Supporting Information Appendix uses stepwise regression modelling to elaborate on the contribution offered by the argument about an incumbency burden. The idea is to compare the tenure effect in models with and without the burden variables. Model 1 and Model 2 use the same LDV specification that was reported above, finding that the inclusion of the burden variables halves the tenure effect (from −0.02 to −0.01).Footnote 16 In other words, part of the cost of ruling that incumbents face seems to be explained by the burden of appearing in political news that is comparatively negative.

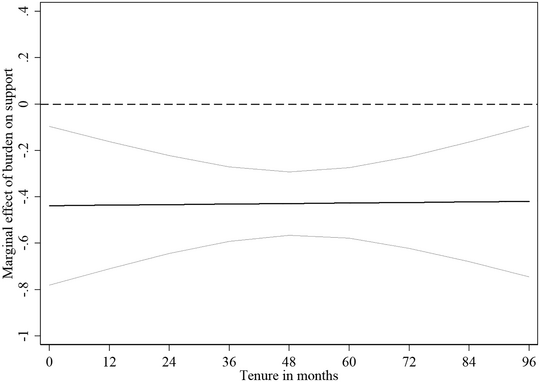

Figure 2 elaborates on the interaction effect from Model 4, Table B1 in the Supporting Information Appendix, showing the marginal effect of burden on support as tenure increases. The results clearly do not support a notion of a third path through which news tone differences impact electoral support, namely that the negative effect of the incumbency burden increases with tenure. According to Figure 2, the incumbency burden has a negative marginal effect on support regardless of how long a government has been in office.Footnote 17

Figure 2. Marginal effect of incumbency burden on incumbency support across tenure. 95 per cent confidence interval. Estimated using Model 4, Table B1 (Supporting Information Appendix).

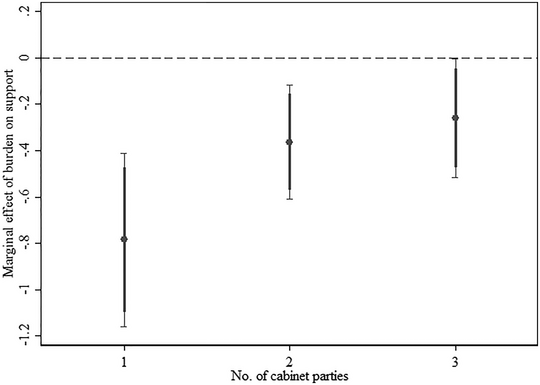

Hypothesis 3 claims that the burden effect on incumbent support is conditioned by the concentration of policy responsibility. To evaluate this claim, we utilize the variation in cabinet size and composition found both over time and across the four political systems included in our data set. We proxy concentration of policy responsibility using the number of cabinet parties. Model 5 in Table B1 (Supporting Information Appendix B) reports the results of a model where the number of cabinet parties and the incumbency burden is interacted. The interaction effect is illustrated in Figure 3, where the marginal effect of burden on support is plotted for cabinets of different sizes.Footnote 18 The figure shows, supporting H3, that the negative burden effect on incumbent support applies more strongly to single‐party cabinets. In fact, a one standard deviation rise in the incumbency burden is associated with a drop of nearly 0.8 percentage points for a single‐party cabinet. In comparison, coalitions appear to be shielded against some of the negative impact from news that governments inevitably will appear in.

Figure 3. Marginal effect of incumbency burden on incumbency support for cabinets of different sizes. Estimated using Model 5, Table B1 in the Supporting Information Appendix. 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals.

Taken together, the results suggest that any conceivable advantage of an incumbency bonus in political communication in no way makes up for the negative electoral effects associated with the incumbency burden. Single‐party cabinets appear more vulnerable to these costs, but the overall story from our sample of cabinets is one of a general, consistent effect: Both single‐party cabinets and coalitions are negatively affected, and there is no sign that they can escape the burden effect at any point during their tenure.

Robustness

The results presented above have been reproduced using alternative model specifications reported in Tables B3 and B4 of the Supporting Information Appendix. The re‐estimations in Table B3 apply three types of standard errors – conventional, Driscoll–Kraay and panel corrected (Beck & Katz, Reference Beck and Katz1995) – of which the latter two are supposed to deal with general forms of cross‐sectional and serial correlation under various circumstances (Hoechle, Reference Hoechle2007). The results across the four different specifications in Tables B1 and B3 are highly similar, which is a positive signal with regards to robust model specification (King & Roberts, Reference King and Roberts2015, p. 177). Next, spurious inferences is a particular challenge when analyzing related time series and practitioners are advised to check alternative models of the dynamic relationship between time series (Philips, Reference Philips2022). Furthermore, there is also a challenge related to reverse causality, considering that some part of the incumbency burden will reflect news about negative (positive) poll results for incumbents (opposition). Although poll coverage is only a limited part of political news, both these challenges suggest that an alternative model specification could be useful. In Table B4 we therefore report the results of an error correction model (ECM, see De Boef & Keele, Reference De Boef and Keele2008). The ECM regresses both lagged and first‐differenced independent variables on a first‐differenced dependent variable. Additionally, Table B4 presents a more limited adjustment of the main model we have reported above, through a general ADL model where lagged values of the incumbency burden is added. A cursory look at the results, without studying the details that these specifications offer, again indicates that the burden effects are robust.

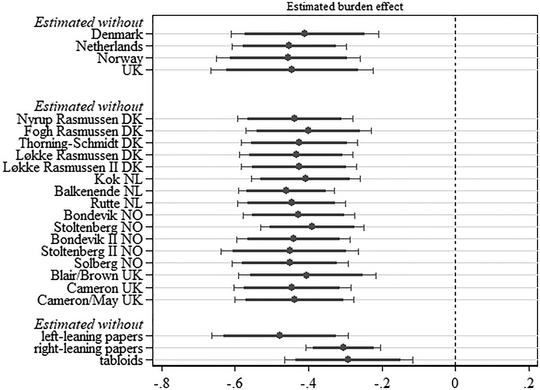

Finally, we address the potential bias that could arise if specific cases or sources in our sample are particularly influential. This is done based on a ‘leave‐one‐out; logic, where we drop one country, one cabinet or one type of newspaper at a time before re‐estimating the models. Results are displayed in Figure 4. Although the estimated coefficients vary, it appears that neither any particular country, cabinet nor a particular type of news outlet is driving the main results of this study.

Figure 4. The estimated effect of the incumbency burden in various jackknife robustness tests. 95 and 90 per cent confidence intervals.

Conclusion

There are few empirical laws within political science, but the cost of ruling is one of them (Cuzan, Reference Cuzán2022). Being in office comes with great political power, over the bureaucracy and the legislative process, and guaranteed media attention that in theory should provide incumbents with a considerable advantage over the opposition. From this perspective, the cost of ruling is also a paradox that requires explanation.

Drawing on the literature about politics and media, we argue that part of the reason why governments lose support relates to the very different ways in which incumbents and the opposition figure in political news. News media pay more attention to incumbents than to the opposition because they are more powerful, an element of political news known as the incumbency bonus. However, while this bonus in theory would afford incumbents more opportunities to strengthen their hold on the electorate, this is not how political journalism works. The policy responsibility that grants incumbents news attention is tightly linked to journalism's professional norm of critical, democratic control. This means that even though incumbents are more often in the news, the tone of the news in which they figure is systematically more negative compared to the tone when the opposition is present. We have labelled this the incumbency burden and find that it is a general feature of political news imbalances. This burden furthermore plays an important role in generating the cost of ruling – an argument that receives consistent support in our models combining extensive data on media coverage of politics with monthly opinion poll data in four countries (the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway) over nearly two decades.

As others have noted with regard to the relation between policy making and media coverage (Grossman, Reference Grossman2022), we believe that the role of political communication in government support deserves much more attention in further research. Our study covers extensive amounts of data, finding interesting patterns in several countries over a long period. We have nevertheless barely scratched the surface and would like to stress the need for research that applies other designs and other data. For instance, extensions of recent work on media coverage of public policy (Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2019) and pledges (Müller, Reference Müller2020; Duval, Reference Duval2019) could prove extremely valuable for studies of government support. In particular, if we are able to distinguish what governments do and how media link policy problems to government (in)action, we should be better equipped to get at the role of news in governing costs.

Finally, our aggregate approach obviously needs to be supplemented when addressing assumptions and mechanisms on the micro level. In keeping with our design, the argument and analyses above rest on a simplified understanding of the electorate that expects a heavier incumbency burden to elicit a decrease in government support. While there are studies of voters at the individual level that would support such a link (e.g., Lengauer & Johann, Reference Lengauer and Johann2013; Nai & Seeberg, Reference Nai and Seeberg2018), the nuances of voter responses to news coverage of various policy problems and incumbents should be further explored in both observational and experimental designs. We are confident that the incumbency burden is a prominent and consequential feature of political communication, but its impact across those that originally voted for the government is bound to be differential and shaped by factors such as political preferences and media exposure.

Our results imply that the existence of critical news media, that is, news media that work according to standard news criteria including a critical view of those holding power, is a crucial part of representative democracy. From the perspective of incumbents, the burden constitutes a continuous constraint in their competition with opposition parties. It might understandably also be perceived as unfair, given that news media focus on unsolved problems and failures while ignoring positive developments and incumbent achievements (Müller, Reference Müller2020). On the other hand, this implies that office power is on loan and that the incumbency burden plays its part in securing office alternation as well as policy representation (Budge, Reference Budge2019, p. 191).

At the same time, a high‐choice media environment involving online news, social media, etc., has put established news media under pressure, particularly in the last decade. If a larger share of the public gets its information about politics and incumbents from outside edited media, the professional journalistic scrutiny of incumbents will reach a smaller audience. While this might be good news for those in power – they might dream of a world with no cost of ruling –, the new media landscape also includes fake news and misinformation that often challenge the elite narratives of governments. Either way, the literature on intermedia agenda‐setting suggests that traditional media still play a leading role vis‐à‐vis emerging media (Harder et al., Reference Harder, Sevenans and Van Aelst2017; Su & Xiao, Reference Su and Xiao2021). We therefore believe our news corpus constitutes a valid basis from which to proxy the information available to the public via the media. Nevertheless, future research should address a more varied selection of news outlets and platforms, studying their impact on the cost of ruling.

Acknowledgements

We thank the EJPR editors and four anonymous reviewers for constructive feedback and comments. We are grateful for comments and suggestions from Will Jennings, Annelien Van Remoortere, Rens Vliegenthart, Erik De Vries, Stefaan Walgrave and Murat Yildirim.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data from the news corpus used to prepare the news variables are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/J6F4PP. Additionally, datasets and code to reproduce the results may be found in the Supporting Information zip‐archive.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article: