INTRODUCTION

Prolonged preservation of nematode parasites is desirable for a variety of reasons, including maintaining characterized parasite strains and supporting research in areas like anthelmintic resistance testing and parasite biology (Höglund et al. Reference Höglund, Daş, Tarbiat, Geldhof, Jansson and Gauly2023; Li et al. Reference Li, Gazzola, Hu and Aroian2023). Techniques for prolonged preservation of important gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants have been widely developed and practiced (Chehresa et al. Reference Chehresa, Beech and Scott1997; Chylinski et al. Reference Chylinski, Cortet, Sallé, Jacquiet and Cabaret2015; Van Wyk et al. Reference Van Wyk, Gerber and De Villiers2000). Nematode cryopreservation protocols developed so far are mainly based on preservation of infective larval (L3) stage (Chylinski et al. Reference Chylinski, Cortet, Sallé, Jacquiet and Cabaret2015; Coles et al. Reference Coles, Bauer, Borgsteede, Geerts, Klei, Taylor and Waller1992). These techniques are highly useful in reducing labour and financial costs associated with obtaining parasite stages for routine experimental purposes (Chehresa et al. Reference Chehresa, Beech and Scott1997; Gasnier et al. Reference Gasnier, Cabaret and Moulia1992). Two techniques have commonly been used for the long-term preservation of infective L3: refrigeration and cryopreservation (Chylinski et al. Reference Chylinski, Cortet, Sallé, Jacquiet and Cabaret2015). Refrigeration may be used to advantage aspects of parasite physiology such as reduced energy metabolism and the presence of an external protective sheath (proteinaceous coat, chitinoid shell and vitelline membrane) that provides resistance against adverse environmental conditions (Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015). Cryopreservation exploits the natural ability of free-living parasite stages to survive extreme environmental conditions such as overwintering (Eckert Reference Eckert1997) and has become the mainstay for maintaining pure strains of nematodes in the laboratory (Chylinski et al. Reference Chylinski, Cortet, Sallé, Jacquiet and Cabaret2015; Coles et al. Reference Coles, Bauer, Borgsteede, Geerts, Klei, Taylor and Waller1992; Van Wyk et al. Reference Van Wyk, Gerber and De Villiers2000).

The basic principle of cryopreservation involves freezing parasites in a manner that prevents intracellular ice formation, which is lethal to the organism (Smyth Reference Smyth and Smyth1990). This can be achieved through rapid shock freezing or the use of cryoprotectants in conjunction with rapid, slow, or hybrid cooling protocols (Eckert Reference Eckert1997). Cryoprotectants help minimize freezing damage by preventing or reducing ice crystal formation, primarily by depressing the freezing point of intra- and extracellular fluids, stabilizing water, or increasing solution viscosity (Eckert Reference Eckert1997; Smyth Reference Smyth and Smyth1990; Wowk Reference Wowk2007). However, the effectiveness of cryopreservation depends on the type and concentration of cryoprotectant used, as well as the rates of cooling and thawing (Miyake et al. Reference Miyake, Karanis and Uga2004). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is one of the most widely used and effective cryoprotectants in nematode cryopreservation due to its ability to penetrate biological membranes by interacting with phospholipids, potentially forming pores and enhancing permeability (Stiernagle Reference Stiernagle2006). Optimal DMSO concentrations typically range between 7.5–10% (Szurek and Eroglu Reference Szurek and Eroglu2011). Despite its widespread use in the cryopreservation of nematode larvae, the potential cryoprotective effects or toxicity of DMSO on nematode eggs remain largely unexplored.

Unlike most gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants, ascarid nematodes such as Ascaridia galli lack a free-living larval stage. All developmental stages of the lifecycle are confined within the eggshell, with the infective stage being the fully embryonated egg (Permin and Hansen Reference Permin and Hansen1998). In established cryopreservation protocols for ruminant nematode L3, larvae are typically exsheathed prior to freezing to allow permeation of cryoprotectants and prevent extracellular ice damage (Chylinski et al. Reference Chylinski, Cortet, Sallé, Jacquiet and Cabaret2015; Van Wyk et al. Reference Van Wyk, Gerber and De Villiers2000). The sheath may provide limited protection during cooling but acts as a barrier at freezing temperatures. This is somewhat analogous to the ascarid eggshell, which may assist with resisting cooling but not freezing damage, especially if impermeable to cryoprotectants like DMSO. This fundamental difference presents unique challenges for cryopreservation of eggs, as commonly used strategies that target free-living L3 larvae—such as exsheathment, direct cryoprotectant contact, and rapid freezing—may not work for eggs.

There have been limited studies published on the effects of low temperatures on A. galli eggs. It has been reported that among the various developmental stages of A. galli eggs, the undeveloped (unembryonated) stages are the most resistant to non-freezing low temperatures (3–6°C) (Ackert and Cauthen Reference Ackert and Cauthen1931). Storage at these temperatures generally inhibits egg development, and eggs must be moved to room temperature (20–30°C) for development to the infective stage to occur (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015, Reference Tarbiat, Rahimian, Jansson, Halvarsson and Höglund2018). However, slightly colder temperatures (such as 0°C ±1) or freezing temperatures appear to have a detrimental effect on the viability of A. galli eggs. For instance, Ackert (Reference Ackert1931) reported that non-embryonated eggs kept at 0°C for one month were unable to reach the infective stage when incubated at 30°C while still viable. Similarly, Levine (Reference Levine1937) found that the eggs were non-viable after 45 days at –1°C. A search of the literature failed to find the effect of low temperatures on the survival of fully embryonated A. galli eggs. In practice, researchers occasionally store embryonated eggs at refrigeration temperatures before their use in artificial infection experiments. However, because embryonated eggs typically require optimal conditions—warmth, moisture, and adequate oxygen (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012; Levine Reference Levine1937; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015)—cold storage may compromise the survival of the already developed larvae (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012). Given that A. galli is on the rise and has gained renewed research interest due to its increasing prevalence in laying hens (Höglund et al. Reference Höglund, Daş, Tarbiat, Geldhof, Jansson and Gauly2023), there is a clear need to identify storage conditions that maintain the viability of A. galli eggs for reliable use in research.

The eggshell of ascarid nematodes is one of the most resistant biological structures and offers a high degree of protection to the internal egg mass or developing embryo (Wharton Reference Wharton1980; Wharton et al. Reference Wharton, Perry and Beane1993). It is impermeable to all substances except lipid solvents, gases, and perhaps liquid water (Wharton, Reference Wharton1980). It is generally accepted that the eggshell of ascarid nematodes is the hardest and most resistant of all nematode eggs. This resistance is due to the structure of the eggshell, which includes a thick chitin-protein layer (Bond and Huffman Reference Bond and Huffman2023; Lysek et al. Reference Lysek, Malinsky and Janisch1985). This enables A. galli eggs to survive extreme conditions and remain infective in the external environment for months (Thapa et al. Reference Thapa, Thamsborg, Meyling, Dhakal and Mejer2017). Although the eggshell has a very different structure from cell membranes and DMSO may not be effective because of this, clarifying this aspect is important for furthering research and development of cryopreservation methods for this parasite and other ascarid nematodes.

The objective of this study was to investigate the survival of both unembryonated and fully embryonated A. galli eggs exposed to cold and freezing temperatures with or without the penetrative cryoprotectant DMSO. The specific propositions tested were: 1) DMSO will protect A. galli eggs from freezing damage when exposed to sub-zero temperatures; 2) DMSO, at concentrations commonly used for cryopreservation (up to 10%), will not have detrimental effects on the viability and developmental capacity of A. galli eggs; and 3) unembryonated A. galli eggs are more resistant to refrigeration than embryonated eggs.

Materials and methods

Ascaridia galli eggs

The experimental subjects of this study were A. galli eggs recovered from freshly recovered mature female worms incubated at 37°C in RPMI media. Details of the procedure for worm and egg harvest have been described in Feyera et al. (Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020). Briefly, freshly harvested A. galli worms were transferred into RPMI media (with 0.1% 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, 250 ng/mL amphotericin B; Sigma-Aldrich Pty Ltd, St Louis, MO, USA) in a glass jar to a volume that covered the worms. The A. galli worms were then maintained for three days at 37°C, changing the media every 24 hours. After every 24 hours, the media containing parasite eggs was collected into 50 mL screw cap Falcon tubes and the jar was rinsed with fresh RPMI media. The egg suspension was then centrifuged (Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, USA) at 425 g for 1 min and eggs concentrated at the bottom of the media were collected using transfer pipettes. The recovered eggs were then stored in boiled and cooled sterile water at 4°C for later use or were subsequently resuspended in 0.1 N H2SO4 (recommended embryonation medium) and incubated aerobically at 26°C for 4 weeks to allow full embryonation (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022).

Two egg developmental stages were defined and used: 1) unembryonted (Fig. 1a): eggs stored in cryovials with lids tightly closed to approximate anaerobic condition at 4°C in distilled water (boiled and cooled) for about 4 weeks from the day of isolation; 2) embryonated (Fig. 1b): eggs aerobically incubated at 26°C in 0.1 N H2SO4 for 4 weeks from the day of isolation. For both categories of eggs, the percentage of pre-storage damage and the viability status was estimated by microscopic examination of 200–300 eggs. In both cases, egg viability was >90% at the start of the experiment.

Figure 1. Representative examples of A. galli egg developmental stages used for the experiment: (a) unembryonated eggs: fertile eggs with no visible cell division process, contained a single cell which almost completely filled the eggshell and appeared granulated; (b) embryonated eggs: egg that had completed development and contained coiled slender motile larvae.

Experimental design and setup

This study employed a 2 × 3 × 3 × 4 factorial experimental arrangement involving four factors: egg developmental stage (unembryonated or embryonated), storage medium (sterile water, 5% DMSO, or 10% DMSO), storage temperature (4, –20, or –80°C), and storage period (1, 2, 4, or 8 weeks). For all storage conditions, concentrated eggs were resuspended in the respective preservation medium (1 mL) and distributed into 1.5 mL cryostorage vials with rubber lids in such a way that each vial contained 1000 viable eggs/mL. There were three replicates of each treatment combination. For freezing treatments, all vials were incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes prior to storage to facilitate permeation of the cryprotectant (DMSO) into the egg. A slow cooling rate (0.3°C/min) was employed for eggs stored at –20, and –80°C (Uga et al. Reference Uga, Araki, Matsumura and Iwamura1983). The detailed experimental design, including treatment groups, number of replicates, and egg survival assessment approaches, is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Experimental design: treatment factors, levels, replicates, and measurements of egg survival.

DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide.

Monitoring survival of eggs

Separate approaches were used to assess the survival of the two egg categories (unembryonated and embryonated) after the various storage periods. For this purpose, the following key terminologies were defined and used: 1) embryonation capacity of unembryonated eggs (ECu), survival of unembryonated eggs (ESu), and survival of embryonated eggs (ESe). To establish the ECu and ESu, the storage medium was replaced with 0.1 N H2SO4 (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022) and incubated at 26°C for 4 weeks under aerobic condition. At the end of incubation period at 26°C, at least 100 eggs from each replicate sample were examined microscopically and the proportion of viable eggs at different stages of development (undeveloped, early development, vermiform, and embryonated (ECu)) or damaged/dead were recorded for each category by adopting morphological classifications described earlier (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Rahimian et al. Reference Rahimian, Gauly and Daş2016; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015). Undeveloped (unembryonated) eggs contained a single granulated cell filling most of the eggshell. Eggs with two or more cells without visible differentiation were classified as early developmental stages. The vermiform stage was identified by a non-motile, tadpole-like embryo occupying nearly the entire capsular space with high terminal opacity. Fully embryonated eggs contained coiled, slender, motile larvae, while eggs showing disrupted shells, shrunken embryonic masses, or abnormal internal structures were considered dead. This classification allowed systematic monitoring of egg development under different storage conditions (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020, Reference Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke, Shifaw and Walkden-Brown2022). The percentage of ESu was estimated as the proportion of eggs in developmental stages other than dead, whereas the ECu is the percentage of unembryonated eggs that demonstrated full embryonation at the end of each observation period. The survival of embryonated eggs (ESe) stored for different periods was evaluated using an in vitro hatching assay, based on a chemical–mechanical method originally developed for A. galli (Dick et al. Reference Dick, Leland and Hansen1973) and later described by Feyera et al. (Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020). Briefly, eggs were washed with 0.9% NaCl, exposed to equal parts of 4% NaOH and 4% NaOCl for 24 hours at 26°C, incubated in 0.2% Tween-80 for 1 hour, and washed again. Larvae were subsequently liberated by centrifugation at 930 × g for 5 min. The liberated larvae were tested for viability using dye (methylene blue) exclusion method, where uptake of dye indicates larval death and inactivation as described earlier (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Shafir et al. Reference Shafir, Sorvillo, Sorvillo and Eberhard2011). Hatched larvae were mixed 1:1 with a 1:10,000 dilution of methylene blue. Viable larvae remained motile and unstained, whereas non-viable larvae absorbed the methylene blue stain. At least 50 liberated larvae were counted and recorded in triplicate tubes.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analysed using JMP® software version 18 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA). The main measurements assessed were ECu, ESu, and ESe under different treatment (storage) conditions, all expressed as percentages. The percentage ESu was estimated as the proportion of all eggs in developmental stages (i.e., the sum of viable undeveloped eggs, early development, vermiform stages, and fully embryonated eggs) other than dead, whereas the percentage ECu was estimated as the proportion of eggs that demonstrated full embryonation at the end of each observation period. Percentages were based on triplicate counts of 100 eggs, hence a total of 300 observations. For eggs stored in the embryonated stage, ESe was estimated as percentage of artificially hatched larvae that were viable based on vital staining. Percentages were based on triplicate counts of 50 larvae, hence a total of 150 observations. Distributions of the data and model residuals were assessed for compliance with the assumptions of analysis of variance (ANOVA). Data complied with the assumptions of ANOVA and transformation of data was not required. Because a different survivability measurement approach was employed for the egg development stages used (unembryonated and embryonated), two separate analyses involving a full factorial ANOVA in the linear model platform of JMP were carried out to evaluate effects of study factors on egg survival parameters. In each analysis, storage media (water, 5% DMSO, or 10% DMSO), storage period (1, 2, 4, or 8 weeks), and their interactions were fitted as fixed effects in a linear model. Storage temperature was removed from the factorial model, as eggs did not survive at –20 or –80°C, resulting in no variation to analyse. All post hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s HSD test and data are presented using least-squares means (LSM). Linear regression was used to test the association between egg survival and storage period, and to determine the rate of decline in survival with storage time by regressing egg survival level against week within treatment groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 throughout the analysis.

Results

Treatment effects of storage temperature and cryoprotectant on the survival of eggs over time

No egg survival was detected at –20°C and –80°C, regardless of the developmental stage or storage medium even after 1 week of storage. At the end of each storage period at these temperatures, eggs with an abnormal intra-capsular mass, disrupted eggshell, and a shrunken internal embryonic mass were observed. In contrast, at a storage temperature of 4°C egg survival was maintained but showed a marked decline over time, irrespective of the developmental stage and storage media used. Consequently, all subsequent survival data are reported only for eggs stored at 4°C.

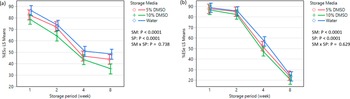

Based on the different survival assessment methods, it was observed that unembryonated A. galli eggs survived refrigeration better than embryonated eggs, regardless of being stored in DMSO or water. Figure 2 presents the differential survival rates for the two egg types, highlighting the clear differences in survival patterns. For all storage media, ESu experienced a rapid decline in survival during the first 4 weeks, which then slowed (Fig. 2a). In contrast, ESe showed little loss during the first 2 weeks, followed by a more rapid decline after 2 weeks of storage through to week 8 (Fig. 2b). At the end of the 8-week storage period, the overall percentage ESu in 10% DMSO, 5% DMSO, and water was reduced to 35.6, 43.8, and 48.4%, respectively (Fig. 2a). The corresponding values for ESe in 10% DMSO, 5% DMSO, and water were 20.7, 22.9, and 23.7%, respectively (Fig. 2b). For ESu the effects of both storage media (P = 0.003) and storage period (P < 0.0001) were significant and there was also significant interaction between these effects (P = 0.0025). The significant interaction was primarily due to a marked reduction in the ESu in 10% DMSO, but not in the other treatments at 8 weeks. In the case of ESe, the effects of storage media (P = 0.0014) and storage period (P < 0.0001) were significant without interaction effects (P > 0.05).

Figure 2. Interaction plots showing survival of unembryonated (a) and embryonated (b) A. galli eggs stored under different media conditions at refrigeration temperature (4°C) over 8 weeks. Values represent LSM ± SE. Storage media are represented by distinct colours (10% DMSO, 5% DMSO, Water). DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide, ESe = survival of embryonated eggs, ESu = survival of unembryonated eggs, LSM = least square means, SE = standard error.

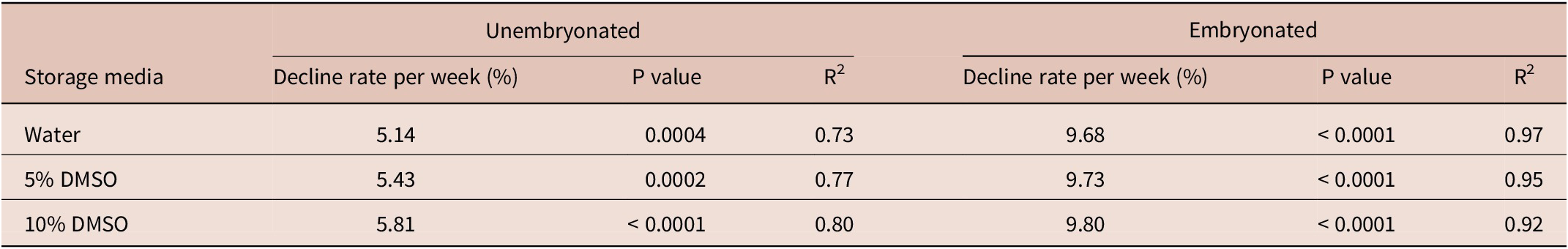

Eggs stored in water and 5% DMSO had similar and higher survival rate (P < 0.05) compared to those stored in 10% DMSO, regardless of their developmental stage. Fitting regression lines over the 8-week period yielded the outcomes summarized in Table 2, showing that ESu demonstrated a much slower rate of weekly decline in overall percentage survival in all storage media compared to ESe. Overall, combining all storage media in the analysis, the decline in ESu over the 8-week experimental period was 5.46% per week, whereas the rate of decline in ESe was 9.74% per week.

Table 2. Differential linear weekly rate of decline in survival of unembryonated (ESu) and embryonated (ESe) eggs following refrigeration (4°C) DMSO or water during 1 to 8 weeks.

DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide.

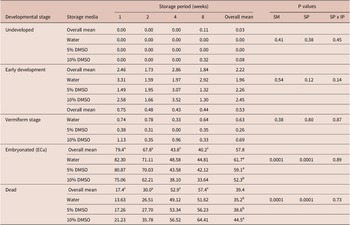

Effect of DMSO on embryonation capacity following refrigeration of unembryonated eggs

Table 3 shows percentages of different A. galli egg developmental stages following pre-embryonation storage at 4°C for 1 to 8 weeks in water with or without DMSO and subsequent aerobic incubation at 26°C in water for 4 weeks to enable embryonation. The vast majority of eggs completed embryonation after 4 weeks of incubation, irrespective of the storage medium used during the pre-embryonation storage at 4°C. Only a very low proportion of eggs (< 4%) remained at early development or vermiform stages. The percentage ECu was significantly (P < 0.0001) affected by both the pre-embryonation storage period and the storage media used, with no significant interaction between the two factors. Eggs stored for only 1 week demonstrated the highest ECu relative to those refrigerated for 2 weeks or more. Eggs stored in water (82.3%) or 5% DMSO (80.9%) showed a higher (P < 0.05) percentage ECu than those stored in 10% DMSO (75.1%) after 1 week of refrigeration. Overall, loss of ECu was slightly more rapid in eggs stored in DMSO than in those stored in water. The rate of decline in percentage ECu of eggs stored in water (y = 81.03 – 5.16x; R2 = 0.75, P = 0.0002), 5% DMSO (y = 79.37 – 5.40x; R2 = 0.73, P = 0.0003), and 10% DMSO (y = 73.68257 – 5.65x; R2 = 0.77, P = 0.0002), respectively, were 5.16, 5.40, and 5.65 %/week.

Table 3. Percentages (LSmeans) of different A. galli egg developmental stages following pre-embryonation refrigeration (1 to 8 weeks) in DMSO or water and subsequent aerobic incubation at 26°C for 4 weeks.

DMSO = dimethyl sulfoxide, SM = storage media, SP = storage period. Different superscripts (a, b, c) within columns and egg developmental category indicate a significant difference between storage media, whereas those within rows and storage weeks (x, y, z) indicate a significant difference between storage period (P < 0.05).

Discussion

This study evaluated the survivability and rate of decline in the survival of unembryonated and fully embryonated A. galli eggs exposed to refrigeration and freezing temperatures in the presence of the penetrative cryoprotectant DMSO. No treatment prevented A. galli eggs from freezing damage, and not a single egg survived even for 1 week of storage at –20°C or –80°C. Above freezing temperatures, the inclusion of DMSO in the storage medium at 4°C caused a moderate concentration-dependent reduction in egg survival with increasing storage time. Survival of eggs declined during storage at 4°C at a higher rate in 10% DMSO compared to water and 5% DMSO. Unembryonated A. galli eggs survived refrigeration better than embryonated eggs, with egg survival declining linearly at almost double rate in the latter (9.74%/week) than the former (5.46%/week).

The first proposition of this study, that DMSO would protect A. galli eggs damage when exposed to sub-zero temperatures, was not supported by the findings. Even though two concentrations of the cryoprotectant and a slow cooling method were applied, no egg survived even for 1 week of storage at –20°C and –80°C. This failure to survive was comparatively rapid and prolonged freezing conditions contrast with the view that the resistant thick shells of ascarid eggs may help them survive extreme low temperatures at least for shorter periods (Cruthers et al. Reference Cruthers, Weise and Hansen1974; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015). Eggs stored at freezing temperatures typically exhibited shell cracks or collapse, shrinkage, loss of the outer coat, internal degeneration, and distorted shape, indicating loss of viability. In contrast, the survival of eggs was maintained after storage at 4°C, irrespective of the storage media employed, with embryonated eggs exhibiting a much more rapid loss of viability over time compared to unembryonated eggs (Fig. 2a, b). There are limited studies on the survival of nematode eggs at sub-zero temperatures even though some short-term success has been claimed for eggs of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Uga et al. Reference Uga, Araki, Matsumura and Iwamura1983) and Parascaris equorum (Koudela and Bodeček, Reference Koudela and Bodeček2006) at sub-zero temperatures above –80°C. For instance, Uga et al. (Reference Uga, Araki, Matsumura and Iwamura1983) reported that eggs of A. cantonensis stored in DMSO survived (50%) cooling to –30°C for about 1 hour, but extremely low survival was noted at lower temperatures. Koudela and Bodeček (Reference Koudela and Bodeček2006) also found that the viability of unembryonated P. equorum eggs was maintained to varying degrees when stored in water at –5 to –20°C for 1–168 hours, but no eggs survived even 1 hour of freezing at –80°C. At freezing temperatures, damage to nematode eggs can occur either by external ice crystals (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zhu, Wang, Liu, Chen and Duan2018) or due to the freezing of the water within eggs, which forms ice crystals that can disrupt cell membranes and other cellular structures (Brambillasca et al. Reference Brambillasca, Guglielmo, Coticchio, Mignini Renzini, Dal Canto and Fadini2013; Jang et al. Reference Jang, Park, Yang, Kim, Seok, Park, Choi, Lee and Han2017; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zhu, Wang, Liu, Chen and Duan2018). DMSO acts as a cryoprotectant by reducing ice crystal formation during freezing and thawing, thus preventing cell damage (Stiernagle Reference Stiernagle2006). It achieves this by lowering the freezing point of water and potentially by interacting with cellular components to stabilize them against the stress of ice formation, indirectly reducing osmotic stress (Mandumpal et al. Reference Mandumpal, Kreck and Mancera2011). DMSO is known for its ability to penetrate biological membranes, and it is thought to do this by interacting with the phospholipids in the membranes, potentially forming pores and increasing permeability (Stiernagle Reference Stiernagle2006). The reason DMSO was unable to provide protection of eggs against freezing damage in the current study is unknown but may relate to difficulties in penetrating the chitinous layer of the nematode eggshell or to the way DMSO interacts with it (Kadlecová et al. Reference Kadlecová, Hendrychová, Jirsa, Čermák, Huang, Grundler and Schleker2024). It has also been reported that traditional slow-cooling methods, often used for cryopreservation, may not be suitable for nematode eggs (James Reference James2004; Kadlecová et al. Reference Kadlecová, Hendrychová, Jirsa, Čermák, Huang, Grundler and Schleker2024; Mickiewicz et al. Reference Mickiewicz, Nowek, Czopowicz, Moroz-Fik, Potărniche, Biernacka, Szaluś-Jordanow, Górski, Antonopoulos and Markowska-Daniel2025), as this approach allows for the formation of larger ice crystals, which are more damaging (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Zhu, Wang, Liu, Chen and Duan2018). Taken as a whole, our data (and that of others) suggest that the prospects for developing a cryopreservation protocol for chicken ascarid eggs at sub-zero temperatures using a cryoprotectant combined with a slow cooling rate are not promising. However, future studies may trial more advanced cryopreservation protocols involving rapid cooling and the use of different cryoprotectants, which may be more effective for cryopreserving nematode eggs.

Our second proposition that DMSO, at concentrations commonly used for cryopreservation, will have little detrimental effect on the viability and developmental capacity of A. galli eggs, was partially supported by the data. Viability was preserved following pre-embryonation storage in DMSO at 4°C, but a moderate concentration-dependent decline in ECu was noted as a function of the storage period. Eggs stored in water and 5% DMSO exhibited similar and better ECu compared to those stored in 10% DMSO, suggesting that DMSO can have a concentration-dependent adverse effect on A. galli egg viability and embryonation capacity. Whether stored in water or DMSO, ECu declined with the storage period at 4°C, at a comparable but slightly lower rate than the 6.2% per week decline observed following storage in water in our previous study (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020). It has been suggested that the toxicity of DMSO on nematode egg viability may be dependent on both dose (Mickiewicz et al. Reference Mickiewicz, Nowek, Czopowicz, Moroz-Fik, Potărniche, Biernacka, Szaluś-Jordanow, Górski, Antonopoulos and Markowska-Daniel2025) and exposure time (Fry et al. Reference Fry, Querol, Gomez, McArdle, Rees and Madrigal2015), meaning higher concentrations and extended periods of exposure lead to greater negative effects. Even though concentrations between 7.5% and 10% DMSO are suggested to be optimal for cryopreservation (Mickiewicz et al. Reference Mickiewicz, Nowek, Czopowicz, Moroz-Fik, Potărniche, Biernacka, Szaluś-Jordanow, Górski, Antonopoulos and Markowska-Daniel2025; Szurek and Eroglu Reference Szurek and Eroglu2011), it can be concluded that DMSO at a 10% concentration is not suitable for cryopreservation of A. galli eggs and has a mild detrimental effect on survival of eggs stored at 4°C.

The last proposition of this study, that unembryonated A. galli eggs are more resistant to refrigeration (4°C) than embryonated eggs, was supported by the findings. The ESe declined at almost double rates for each week of storage at 4°C in all three storage media, compared to the corresponding change in overall ESu (Table 2). After 8 weeks of refrigeration, the percentage ESe stored in water was reduced to only 20.7%, compared to unembryonated eggs, whose overall ESu was maintained at 43%. Our data indicate that if refrigerated post-embryonation, A. galli eggs may experience a complete loss of larval viability by as early as 10–12 weeks of storage, whereas for the unembryonated form this may be delayed to 18–20 weeks, depending on the storage media employed. This observation aligns with earlier reports indicating that among the various developmental stages of A. galli eggs, the unembryonated stages are the most resistant to non-freezing low temperatures (0–6°C) and are thus suitable for storage at refrigeration temperatures (Ackert and Cauthen Reference Ackert and Cauthen1931; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015). It has been suggested that undeveloped eggs, which are essentially in a dormant state, can tolerate cold temperatures more easily than embryonated eggs (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Jansson and Höglund2015). Larvae that have completed in ovo development require optimal conditions, such as oxygen saturation, suitable temperature (20–30°C), and humidity for the embryo to continue its normal metabolic activities (Feyera et al. Reference Feyera, Ruhnke, Sharpe, Elliott, Campbell and Walkden-Brown2020; Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Rahimian, Jansson, Halvarsson and Höglund2018). In the present study, eggs were kept in storage vials with lids closed, and a relative lack of oxygen within this system may have contributed to the more rapid mortality rate of the embryonated eggs compared to the undeveloped eggs. Previous studies have suggested that anaerobic conditions maximize the survivability of undeveloped eggs at 4°C for a projected 40 weeks, whereas aerobic conditions are required to maximize survival after embryonation (Shifaw et al. Reference Shifaw, Feyera, Elliott, Sharpe, Ruhnke and Walkden-Brown2022; Tarbiat et al. Reference Tarbiat, Rahimian, Jansson, Halvarsson and Höglund2018). Refrigeration slows down or halts all biochemical processes, potentially leading to cell necrosis and gradual deterioration of larvae, eventually resulting in death (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Pyo, Hwang, Park, Hwang, Chai and Shin2012). Thus, it can be concluded that the storage of A. galli eggs at refrigeration temperatures after full embryonation provides inferior duration of survival compared to undeveloped eggs.

The practical implication of our results and those of others is that cryopreservation of A. galli or other ascarid eggs remains elusive. Until a breakthrough in this regard, further optimization of storage methods at temperatures above freezing is warranted with opportunities available for improved duration of storage of both unembryonated and embryonated eggs. Nonetheless, while this study examined temporal changes in egg survival and development under different storage conditions, the key measure of biological relevance is the infectivity of embryonated eggs. Morphological viability does not necessarily indicate infectivity (Rahimian et al. Reference Rahimian, Gauly and Daş2016), as prolonged storage or suboptimal conditions may reduce larval vitality and infection potential in chickens (Elliott Reference Elliott1954). Future studies should therefore assess the infectivity of stored embryonated eggs through controlled trials to confirm that morphological survival reflects true infective capacity. Moreover, the potential utility of stored unembryonated eggs in in vitro assays, such as larval development tests, also warrants further investigation.

Conclusions

We conclude that cryopreservation of A. galli eggs by slow freezing in the presence of 5 and 10% DMSO is not feasible. Thus, further optimization of storage methods at non-freezing temperatures is warranted to enable the maintenance of viable infective stocks for research. In addition to its lack of cryoprotective effect against egg damage, DMSO exhibited moderate toxicity to eggs at 10%, with increasing exposure time. Given that DMSO is widely included in in vitro parasite assay media, it may compromise assay results if used at this concentration. Undeveloped eggs survive refrigeration longer than embryonated eggs under sealed storge conditions and are thus more suitable for prolonged preservation at 4°C. Nevertheless, given that egg development stage, temperature, oxygen saturation, and storage media can all interact in complex ways to influence egg survival, ongoing research into optimisation of storage at temperatures above freezing is indicated.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Michael Raue and Danielle Smith, staff at the University of New England, Australia, for their technical support during the study.

Financial support

This research was funded by Australian Eggs Ltd. Project 1BS003. Teka Feyera was supported by a University of New England international postgraduate scholarship.

Competing interests

None.