Impact statement

Succession is an inevitable natural process. Succession occurs in biocrusts, but microhabitat, mainly microclimate, controls the speed of this natural process, causing it to vary at various points in space. Realizing this is a step towards improving our understanding of the spatial and temporal distribution of biocrusts.

Because biocrusts have multiple functions in the ecosystem, it is crucial to understand their dynamics for the sustainable management of semi-arid environments. In particular, it is an important advance for biocrust conservation.

Biocrusts should be protected, at least in areas where they are dominant, because they are highly biodiverse, protect the soil against erosion, act as carbon sinks and drive pedogenesis where vegetation is sparse. They are a useful indicator of multiple critical functions (multifunctionality) and provide effective ecosystem conservation. Biocrust conservation can be very important because, to date, very little can be done to rebuild lichen biocrusts once they are destroyed. In this context, a deeper understanding of the dynamics and distribution of biocrusts is very beneficial for the currently thriving body of research that explores the possibilities of using biocrusts to restore degraded areas. In this sense, the concept of mature cyanobacteria-dominated biocrust, including dark cyanobacteria and some pioneer lichens, could be quite useful. Moreover, the biocrusts of the Tabernas Desert are a fundamental component of an ecosystem that is perhaps unique in Europe.

Introduction

Succession is a natural process by which the composition of a community changes over time (Clements, Reference Clements1916; Drury and Nisbet, Reference Drury and Nisbet1973; Connell and Slatyer, Reference Connell and Slatyer1977). Succession in biocrusts has received extensive mention in the literature (Eldridge and Greene, Reference Eldridge and Greene1994; Belnap and Eldridge, Reference Belnap, Eldridge, Belnap and Lange2003; Belnap et al., Reference Belnap, Büdel, Lange, Belnap and Lange2003a; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008; Büdel et al., Reference Büdel, Darienko, Deutschewitz, Dojani, Friedl, Mohr and Weber2009; Zhuang et al., Reference Zhuang, Zhang, Zhao, Wu, Chen and Zhang2009; Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Domingo, Cantón, Trasar-Cepeda, Leirós and Gil-Sotres2012a, Reference Miralles, Lázaro, Sánchez-Marañón, Soriano and Ortega2020; Drahorad et al., Reference Drahorad, Steckenmesser, Henningsen, Lichner and Rodný2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Rossi, Deng, Liu, Wang, Adessi and De Philippis2014; Navarro-Noya et al., Reference Navarro-Noya, Jimenez-Aguilar, Valenzuela-Encinas, Alcántara-Hernandez, Ruiz-Valdiviezo, Ponce-Mendoza, Luna-Guido, Marsch and Dendooven2014; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Cantón, Asensio and Domingo2015; Kidron, Reference Kidron2019; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Zhang, Wang, Zhou, Ye, Fu, Ke, Zhang, Liu and Chen2020; Geng et al., Reference Geng, Zhou, Wang, Peng, Li and Li2024; Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024). Because succession implies changes in species, it can generate biocrust types, that is, communities dominated by different autotrophic organisms, such as cyanobacteria, lichens and mosses, and these types are often considered successional stages. However, Kidron (Reference Kidron2019) and Kidron and Xiao (Reference Kidron and Xiao2024) claimed that referring to biocrust types as successional stages is only justified when stages in recovery plots are compared with control plots, as crust types occupying different locations may be due to distinct abiotic conditions, which affect the dominance of certain photoautotrophs.

Therefore, we wonder: are different crust types at the same place distinct successional stages, or are they distinct communities shaped by microhabitat differences? This may not always be obvious, mainly because (i) there is evidence that the habitat controls the crust type; and (ii) biocrusts usually considered early-successional seem invariant for decades at some sites. However, most scholars are probably aware that both succession and habitat shape crust types. Therefore, we raise the question of how succession and microhabitat interact, using the Tabernas region as our study area. This includes the sites of Tabernas and Sorbas.

According to Kidron et al. (Reference Kidron, Barzilay and Sachs2000, Reference Kidron, Vonshak and Abeliovich2009, Reference Kidron, Vonshak, Dor, Barinova and Abeliovich2010), all five crust types defined at the Nizzana Research Station (in the Negev Desert) are associated with different microhabitats. Similarly, in the Tabernas region, biocrust types are distributed according to topographical microhabitats (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Alexander, Puigdefábregas, Alexander and Millington2000; Canton et al., Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Del Barrio, Solé-Benet and Lázaro2004a; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008). Biocrust type also depends on habitat in other drylands across the world, such as South Africa (Thomas and Dougill, Reference Thomas and Dougill2006), Argentina (Navas Romero et al., Reference Navas Romero, Herrera Moratt, Martinez, Rodriguez and Vento2020) or California (Pietrasiak et al., Reference Pietrasiak, Johansen, LaDoux and Graham2011, Reference Pietrasiak, Drenovsky, Santiago and Graham2014). Microhabitat affects biocrust type mainly through its effects on microclimate, strongly through incident solar radiation and water availability (Kidron et al., Reference Kidron, Vonshak and Abeliovich2009; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Büdel, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016c; Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024).

Succession follows different pathways under different climates (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016b, Reference Weber, Büdel, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016c). In general, when the site is drier, the possibility of succession occurring is lower because it is limited by the lack of water (Felde et al., Reference Felde, Rodriguez-Caballero, Chamizo, Rossi, Uteau, Peth, Keck, De Philippis, Belnap and Eldridge2020). Moreover, the 53-year biocrust monitoring study in Utah (USA) by Finger-Higgens et al. (Reference Finger-Higgens, Duniway, Fick, Geiger, Hoover, Pfennigwerth, Van Scoyoc and Belnap2022) showed that climate change can alter crust type. Our results suggest that the same occurs between microclimates at a local scale.

Succession could occur via Connell and Slatyer’s (Reference Connell and Slatyer1977) facilitation model, because early-successional species condition a site in favour of late-successional species (Bowker, Reference Bowker2007; Colesie et al., Reference Colesie, Scheu, Green, Weber, Wirth and Büdel2012). Potential mechanisms, direct by facilitation or competition (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Callaway, Valladares and Lortie2009; Li et al., Reference Li, Colica, Wu, Li, Rossi, De Philippis and Liu2013; Soliveres and Eldridge, Reference Soliveres and Eldridge2020), or indirect by altering site conditions, are poorly understood (Soliveres and Eldridge, Reference Soliveres and Eldridge2020).

Cyanobacteria-dominated biocrust is widely assumed to be the first stage. Some claim that there is only evidence of two stages: cyanobacteria and, later, lichens or mosses (Eldridge et al., Reference Eldridge, Freudenberger and Koen2006; Zhuang et al., Reference Zhuang, Zhang, Zhao, Wu, Chen and Zhang2009; Uclés et al., Reference Uclés, Villagarcía, Cantón, Lázaro and Domingo2015). Others assume three stages: cyanobacteria, lichens and mosses (Felde et al., Reference Felde, Peth, Uteau-Puschmann, Drahorad and Felix-Henningsen2014; Deng et al., Reference Deng, Zhang, Wang, Zhou, Ye, Fu, Ke, Zhang, Liu and Chen2020; Li and Hu, Reference Li and Hu2021; Sun and Li, Reference Sun and Li2021). In our Tabernas studies, we often referred to a greater number of hypothetical stages, describing the biocrust types (Lopez-Canfin et al., Reference Lopez-Canfin, Lázaro and Sánchez-Cañete2022a, Reference Lopez-Canfin, Lázaro and Sánchez-Cañete2022b; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023; Rubio and Lázaro, Reference Rubio and Lázaro2023).

The objectives of this review article are (i) to show that, in the Tabernas region, crust types can be considered authentic successional stages even though both succession and microclimate act simultaneously in generating them; and (ii) to provide a conceptual model of biocrust succession for Tabernas, including the microclimate effect and the conditions under which succession occurs.

To achieve this, we present four case studies of direct succession – two unpublished – along with a review of publications from the Tabernas region based on crust types, hypothesized to be successional stages, and covering a range of biocrust structural and functional properties. Finally, we synthesize the work and propose a model.

Case study system

The Tabernas region includes extensive areas with high biocrust cover that have not been disturbed for more than 35 years. Of the 63 articles found in Scopus that deal with more than one biocrust type at Tabernas, none explicitly discounts the idea that succession generates biocrust types. Four (6.3%) seemed to contest it implicitly or were unclear on this position. Fourteen (22.2%) assumed, although not explicitly, that biocrust type corresponded to successional stages. Forty (63.5%) explicitly stated that biocrust type equates to succession stage. Before 2008, authors referred to succession only obliquely or indirectly. Lázaro et al. (Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008) provided evidence of the replacement of cyanobacterial biocrust by lichens over time and had two effects: (i) after this, the vast majority of articles hypothesized biocrust types as successional stages, starting with Chamizo et al. (Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Rodríguez-Caballero, Domingo and Escudero2012c) and Miralles et al. (Reference Miralles, Domingo, Cantón, Trasar-Cepeda, Leirós and Gil-Sotres2012a); and (ii) this inspired us to start long-term monitoring experiments to test the relationship between biocrust type and successional stage.

We propose that (i) biocrust types can be considered as successional stages at Tabernas in cases other than recovery studies, allowing for space-for-time sampling, as this is compatible with the association of biocrust type with microclimate (Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Román, Chamizo, Roncero-Ramos and Cantón2019; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008; Li and Hu, Reference Li and Hu2021). (ii) The biocrusts at Tabernas would exhibit the following progression: physical; incipient cyanobacterial; mature cyanobacterial; lichen biocrust dominated by Squamarina lentigera and/or Diploschistes diacapsis (Squamarina); and lichen biocrust characterized by Lepraria isidiata (Lepraria; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023). At the Sorbas site, the last stage can be a moss-dominated biocrust. (iii) On a human time scale, succession in biocrusts only occurs where the microclimate allows for it. (iv) Succession can sometimes split (following different pathways in different microhabitats) and be retrogressive. Often, succession is imagined as a simple, linear, one-way process. However, our data from Sorbas and the in-situ drought experiment by Rubio and Lázaro (Reference Rubio and Lázaro2025) show the existence of bifurcations and regressive succession, also noted by Kidron and Xiao (Reference Kidron and Xiao2024).

Tabernas

Most research has been done at the El Cautivo field site, located at 37.011°, 2.442°, 240–320 m a.s.l., which is a representative part of the Tabernas Desert. It is a badlands area that has developed since the late Pleistocene era (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Calvo, Arnau, Mather and Lázaro2008) in the Tortonian marine marls (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Domingo, Solé-Benet and Puigdefábregas2001; Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Domingo, Solé-Benet and Puigdefábregas2002). It receives 200–240 mm/yr of rainfall, and the mean annual air temperature is 18–19 °C (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Rodrigo, Gutiérrez, Domingo and Puigdefábregas2001; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Rodríguez-Tamayo, Ordiales, Puigdefábregas, Mota, Cabello, Cerrillo and Rodríguez-Tamayo2004). The meso-climatic conditions favour biocrust development (Lázaro, Reference Lázaro and Pandalai2004). Soils are silty (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Solé-Benet and Lázaro2003). Vegetation is patchy, dominated by dwarf shrubs or tussock grasses. Biocrusts dominate about one-third of the territory and also occur in another third in the plant interspaces. For more information, see Calvo-Cases et al. (Reference Calvo-Cases, Harvey, Alexander, Canton, Lazaro, Sole-Benet, Puigdefabregas, Gutiérrez and Gutiérrez2014) and Lázaro et al. (Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023).

Sorbas

The Sorbas field site is about 30 km east of Tabernas, at 37.083, 2.066° and 397 m a.s.l. The mean annual temperature is 17 °C, and rainfall is 274 mm/yr. Lithology consists of Miocene gypsum outcrops, and the soils are Gypsiric Leptosols. It has 30–40% plant cover, comprising tussock grasses and shrubs or dwarf shrubs often dominated by gypsophilous species. Over half of the plant interspaces are covered by biocrusts dominated by lichens, cyanobacteria or mosses in the wetter years. Additional site information is shown in the Supplementary Material.

Direct research on biocrust succession

Initial photographic monitoring

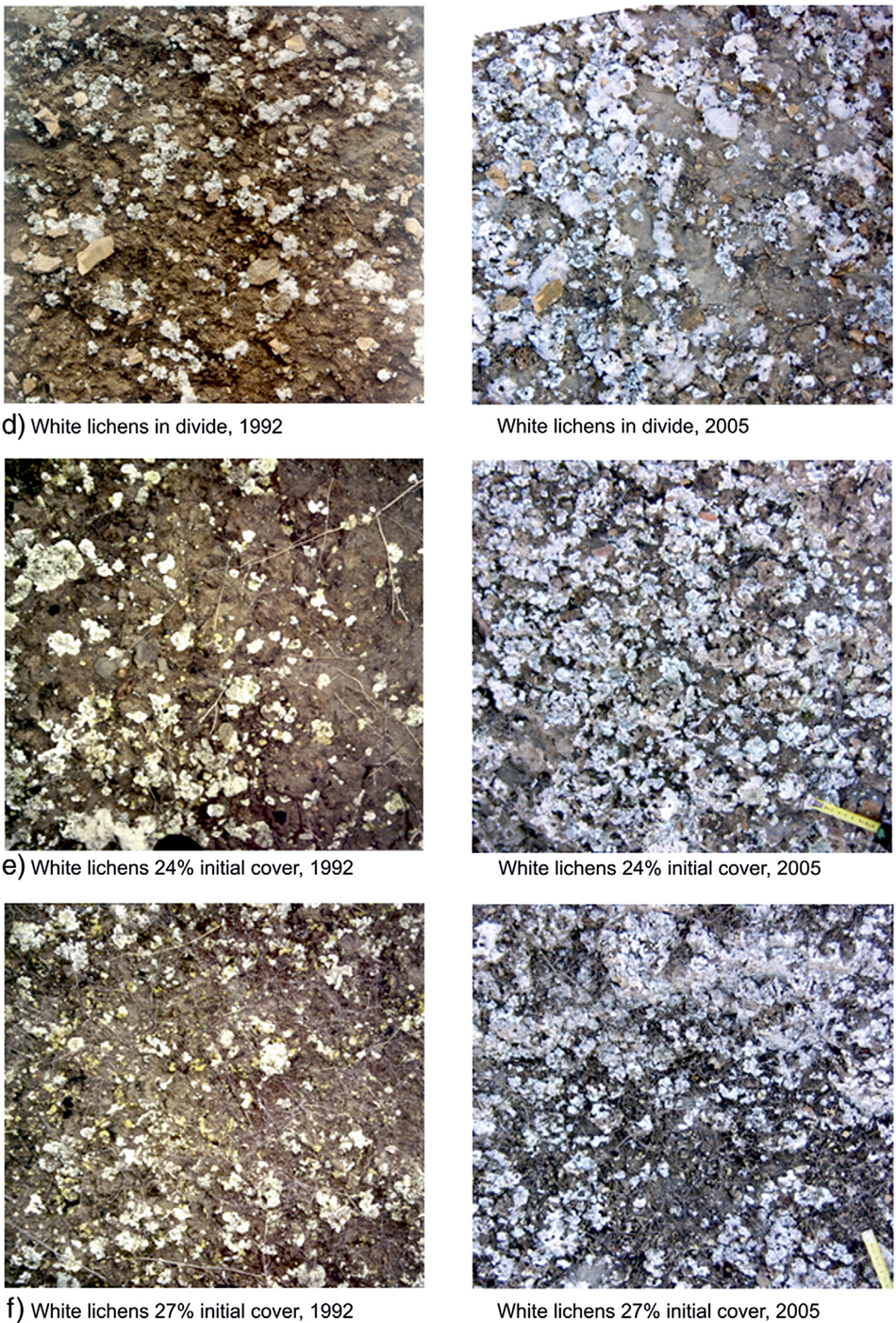

A preliminary 13-year photographic monitoring at Tabernas showed replacement of cyanobacteria by lichens over time, prompting a recovery experiment in 2005 to remove the biocrust of four biocrust types (Cyanobacteria, Squamarina, Diploschistes and Lepraria) in representative areas where they were dominant (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008).

Recovery of various biocrust types

Rubio and Lázaro (Reference Rubio and Lázaro2023) published the recovery patterns of the four biocrust types following 17 years of in situ monitoring. Their main results are as follows (see their Figure 1):

-

(i) The cyanobacterial biocrust cover recovered in just 8 years and recovered thickness in about 12 years, whereas the cover of the Squamarina or Diploschistes biocrust had not fully recovered in 2021, and the recovery of the Lepraria biocrust was even slower. Several authors have found that the ability to colonize and the growth rate of microbial crusts are greater than those of lichen or moss crusts (Belnap and Eldridge, Reference Belnap, Eldridge, Belnap and Lange2003; Dojani et al., Reference Dojani, Büdel, Deutschewitz and Weber2011; Lorite et al., Reference Lorite, Agea, García-Robles, Cañadas, Rams and Sánchez-Castillo2020)

-

(ii) In the three lichen-dominated communities, a cyanobacterial biocrust forms first, reaching an extensive cover before lichens are relevant, consistent with studies in the Succulent Karoo in South Africa (Dojani et al., Reference Dojani, Büdel, Deutschewitz and Weber2011).

-

(iii) Lichens can colonize empty spaces if they are sufficiently stable (sensu Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024), but the spaces are not empty for long because cyanobacteria colonize them faster. Consequently, most lichens develop on cyanobacteria. Lan et al. (Reference Lan, Wu, Zhang and Hu2012) claimed that lichens require a previous cyanobacterial development. Each successional stage is determined by the resources provided by the previous stage (Deng et al. (Reference Deng, Zhang, Wang, Zhou, Ye, Fu, Ke, Zhang, Liu and Chen2020).

-

(iv) One plot suffered a boot print in its lower left quadrat, only once, in the second year (Figure 1h). For quite a few years, that quadrat had very little biocrust. Lichens colonization could not be sustained. The development of the cyanobacteria around the footprint resulted in the formation of a depression. When the cyanobacterial crust finally developed in the depression, it became less apparent and is now being colonized by lichens.

Figure 1. This is part of Figure 3 of Lázaro et al. (Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008), evidencing replacement of cyanobacterial biocrust by lichenic biocrust from a 13-year in situ photographic monitoring at the Tabernas Desert. In the early 1990s, we named ‘white lichens’ to the biocrust dominated by light lichens, but that biocrust corresponds to the Squamarina biocrust used here and includes a diversity of lichens, like the yellow Fulgensia seen in the photos.

Additional monitoring at Sorbas

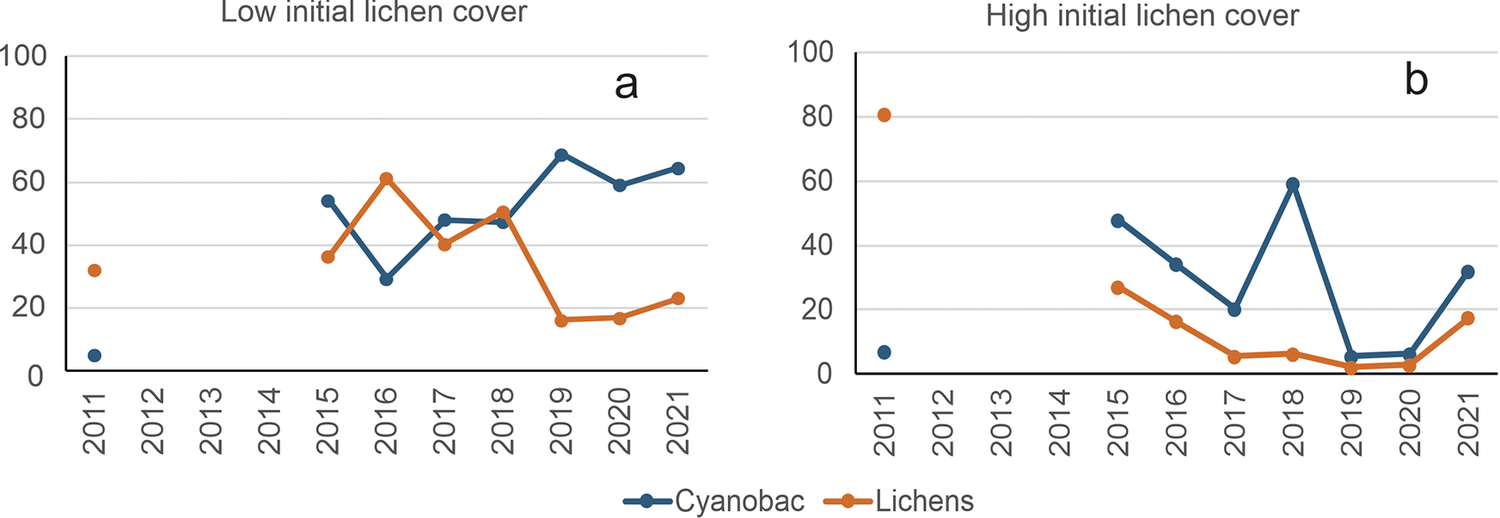

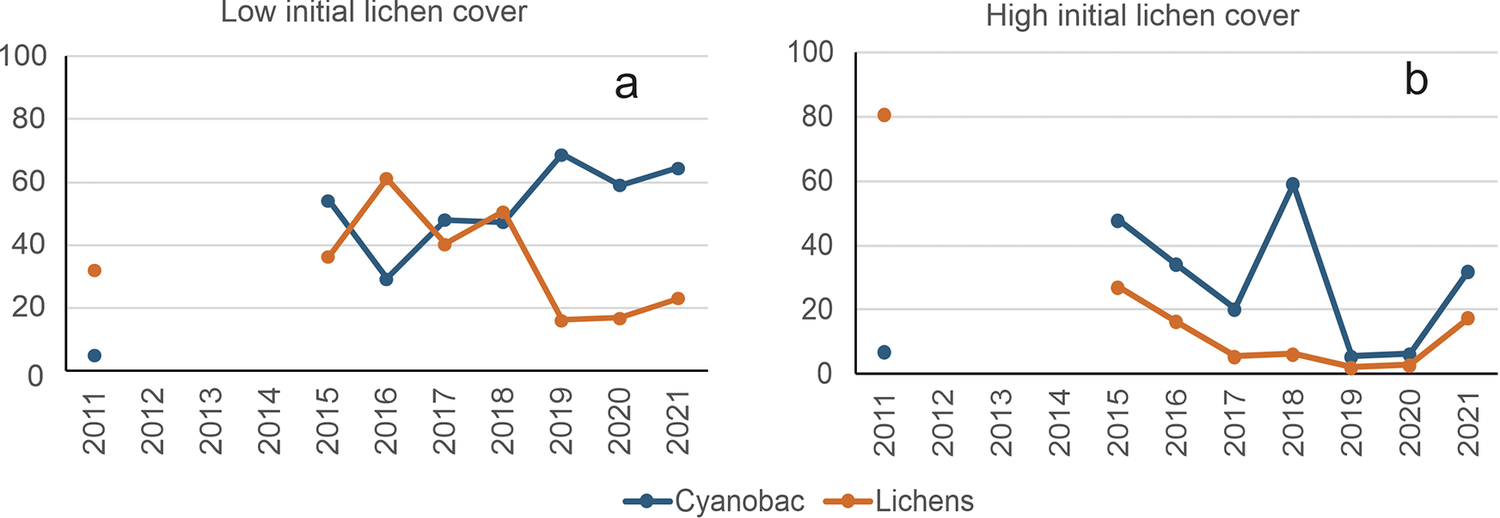

This 11-year monitoring program, distinguishing high (>60%) and low (<20%) initial lichen cover, was a climatic change study (Maestre et al., Reference Maestre, Escolar, Ladrón de Guevara, Quero, Lazaro, Delgado-Baquerizo, Ochoa, Berdugo, Gozalo and Gallardo2013; de Guevara M et al., Reference Ladrón de Guevara, Lázaro, Quero, Ochoa, Gozalo, Berdugo, Uclés, Escolar and Maestre2014). The control plots provide examples of progressive (from cyanobacteria to lichens) and regressive succession (Figure 2). The significant changes over time in some of those plots without treatments and under the same microclimate show that there are unknown intrinsic factors potentially driving biocrust succession.

Figure 2. Evidence of succession in biocrusts in the Sorbas experimental area. Graph a: Progressive succession between 2011 and 2016 in a plot with low initial lichen cover. Graph b: Regressive succession during the same period in a nearby plot that started with high lichen cover; it is noteworthy that cyanobacteria increase while lichens decrease. Both are control plots without any treatment. Covers were approximated from sums of species frequencies.

During the first 4 years, lichen cover increased very slowly (Figure 2a), whereas cyanobacteria increased quickly. Once cyanobacteria reached about 55% cover, lichens increased quickly, reaching 60% in 1 year, partly replacing the cyanobacteria. When lichens decreased, cyanobacteria increased (Figure 2a, Figure 2b).

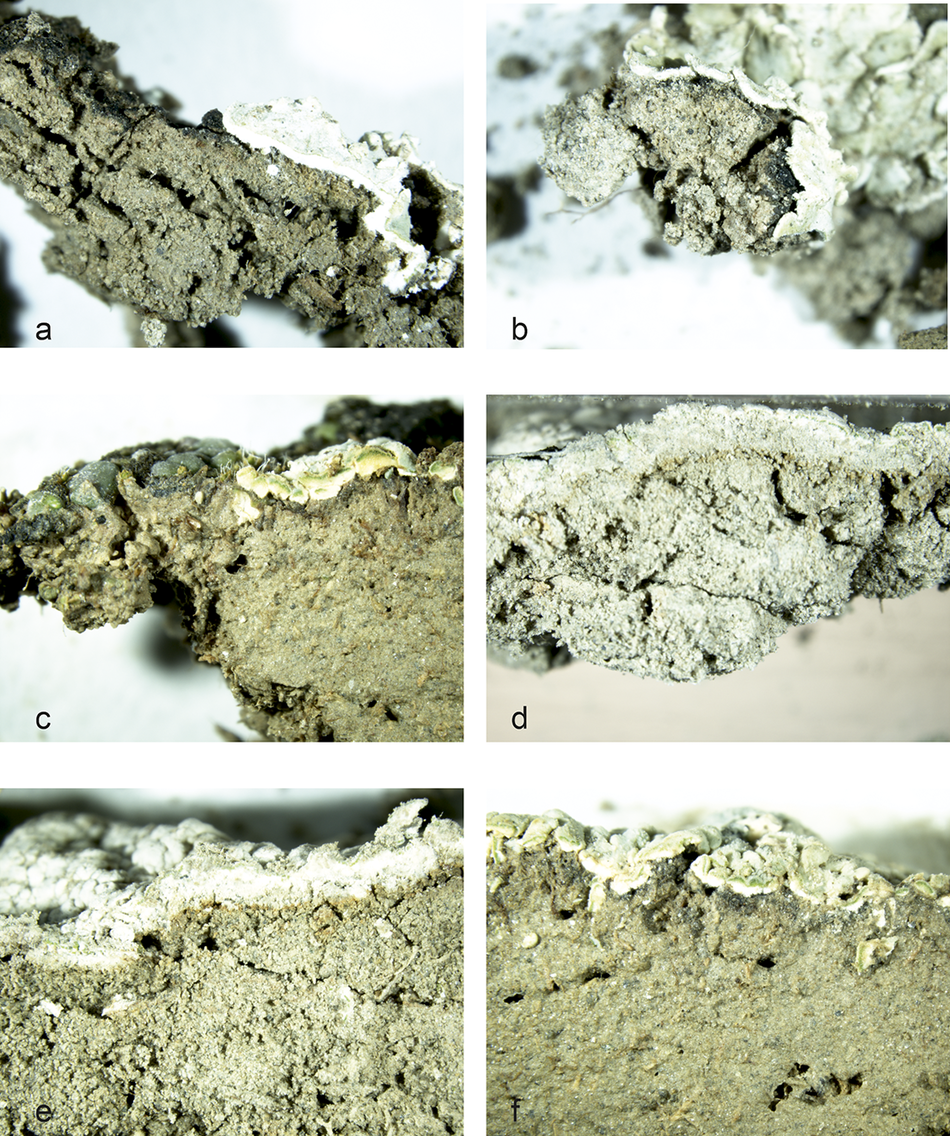

Biocrust micro-profiles

We randomly collected 40 intact soil samples with lichen biocrust, using 9-cm Petri dishes. In the laboratory, we cut small portions of the samples perpendicularly to the surface and obtained 114 photographs using a stereomicroscope. In some of the micro-profiles (Figure 3), we found lichen thalli over a thin horizon of dark or light cyanobacterial biocrust with an appearance like that of the cyanobacterial biocrust when it is alone. The dark cyanobacterial biocrust progressively disappeared towards the centre of the lichen thallus, which is likely its oldest section (Figure 3a).

Figure 3. Some examples of micro-profiles of unaltered biocrusted soil showing lichens developing over a thinner dark or light cyanobacterial biocrust. Squamarina on dark cyanobacterial biocrust is shown in photos a, b, c and f; photo c also shows Toninia on dark cyanobacteria. Photos d and e show Diploschistes developed on light cyanobacterial biocrust.

Indirect approaches: functional properties of crust types hypothesized as succession stages

These studies reinforce the understanding that succession shapes crust types because they all stem from the same hypothetical successional sequence.

Shifts in microbial community composition

At Tabernas, microbial composition changes throughout succession. The phylum Cyanobacteria, representing 21.9% of the bacteria in the cyanobacterial biocrust, was reduced by only 2.2% in the hypothetical latest-successional Lepraria crust (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Lázaro, Sánchez-Marañón, Soriano and Ortega2020). Differences in microbiota between Incipient and Mature cyanobacteria crusts were mainly due to phyla Actinobacteria (Actinomycetota) and Cyanobacteria, which comprise 14.4 and 12.4% of Incipient and 9.8 and 21.9% of Mature biocrusts, respectively (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Lázaro, Sánchez-Marañón, Soriano and Ortega2020). Incipient cyanobacteria were dominated by the bundle-forming cyanobacteria, Microcoleus spp., whereas Mature cyanobacteria were dominated by unicellular cyanobacteria, mainly the lichen photobiont Chroococcidiopsis sp. (Roncero-Ramos et al., Reference Roncero-Ramos, Muñoz-Martín, Cantón, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Mateo2020). The soil micro-fungi species also differed among these biocrust types/stages (Grishkan et al., Reference Grishkan, Lázaro and Kidron2019). The mechanisms driving changes in microbial composition include the metabolites excreted in soil, which are different according to the biocrust type (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Jorge-Villar, van Wesemael and Lázaro2017), as they influence the composition of the soil microbiota (Boustie and Grube, Reference Boustie and Grube2005).

Soil microbiota also changed in other areas depending on the biocrust type (Chilton et al., Reference Chilton, Neilan and Eldridge2018; Sorochkina et al., Reference Sorochkina, Velasco Ayuso and Garcia-Pichel2018; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Li, Xiong, Kou, Zou, Jiao, Yao, Wang, Zhang and Li2024). Maier et al. (Reference Maier, Tamm, Wu, Caesar, Grube and Weber2018) reported an increase in abundance and diversity of the heterotrophic microbiota associated with biocrust succession. Li and Hu (Reference Li and Hu2021) showed that in the regions of China where the three successional stages (bacteria, lichens and mosses) were present, biocrust type, rather than soil or microclimate, accounted for the greatest differences in microbial communities.

Water cycle and availability

At Tabernas, as succession progresses, infiltration and water content increase and runoff (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Lázaro, Solé-Benet and Domingo2012a; Rodriguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodriguez-Caballero, Cantón, Chamizo, Lázaro and Escudero2013), Runoff Length (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Calvo-Cases, Lázaro and Molina2015) and Minimum Runoff Length decreases (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Calvo-Cases, Arnau-Rosalén, Rubio, Fuentes and López-Canfín2021). Soil moisture, water holding capacity and non-rainfall water uptake also increase (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Rodríguez-Caballero and Domingo2016b; Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Chamizo, Rodriguez-Caballero, Lázaro, Roncero-Ramos, Román and Solé-Benet2020; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Moro and Cantón2021), but evaporation remains similar (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Domingo and Belnap2013). These changes are already noticeable when moving from the Incipient to the Mature cyanobacterial biocrust (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Chamizo, Rodriguez-Caballero, Lázaro, Roncero-Ramos, Román and Solé-Benet2020). Thus, succession increases water availability (Uclés et al., Reference Uclés, Villagarcía, Cantón and Domingo2013; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Belnap, Eldridge, Canton, Malam Isa, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016a).

Globally, we find that the hydrological behaviour of biocrusts can vary considerably depending on the underlying soil (Warren, Reference Warren, Belnap and Lange2003b). Biocrust development progressively increases infiltration in places with non-sandy soils, as in Tabernas (Eldridge and Greene, Reference Eldridge and Greene1994; Belnap et al., Reference Belnap, Wilcox, Van Scoyoc and Phillips2013, among others), which is due to three main non-exclusive mechanisms: (i) an increase in surface roughness (Kidron et al., Reference Kidron, Monger, Vonshak and Conrod2012; Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Cantón, Chamizo, Afana and Solé-Benet2012); (ii) an increase in large, irregular, elongated and interconnected pores (Miralles-Mellado et al., Reference Miralles-Mellado, Cantón and Solé-Benet2011); and (iii) increases in soil organic carbon (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Sun, Xu and Zhao2019). However, where the soil is sandy, the effect of biocrust development is the opposite, also increasing with succession, as they progressively accumulate finer soil particles and have a greater capacity for both pore clogging and water holding (Kidron, Reference Kidron2007; Malam Issa et al., Reference Malam Issa, Défarge, Trichet, Valentin and Rajot2009, Reference Malam Issa, Valentin, Rajot, Cerdan, Desprats and Bouchet2011; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hasi and Wu2012).

Erodibility and soil losses

At Tabernas, soil loss strongly decreases throughout succession (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Lázaro, Solé-Benet and Domingo2012a, Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Román and Cantón2016c; Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023). Solute (Lazaro and Mora, Reference Lazaro and Mora2014; Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Chamizo, Rodriguez-Caballero, Lázaro, Roncero-Ramos, Román and Solé-Benet2020) and organic carbon (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Román, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Moro2014; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Román and Cantón2016c) export also decline.

It is widely accepted that biocrusts have a greater soil protection when the crust is more developed, that is, successionally and greater cover (Warren, Reference Warren, Belnap and Lange2003a; Knapen et al., Reference Knapen, Poesen, Galindo-Morales, De Baets and Pals2007; Belnap and Büdel, Reference Belnap, Büdel, Belnap, Weber and Büdel2016; Gao et al., Reference Gao, Sun, Xu and Zhao2019). This is the most relevant biocrust effect (and service) at the ecosystem scale. Bowker et al. (Reference Bowker, Belnap, Bala Chaudhary and Johnson2008) showed that the biocrust chlorophyll a content explains the degree of protection against erosion, because chlorophyll increases with biocrust succession and cover development. Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Qin, Weber and Xu2014) and Gao et al. (Reference Gao, Sun, Xu and Zhao2019) also found decreasing erodibility with the biocrust successional development at the Loess Plateau region in China.

Changes in physical and chemical soil features

At Tabernas, organic carbon, nitrogen, nutrient and exopolysaccharide content increase throughout succession (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Solé-Benet and Domingo2004b; Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, van Wesemael, Cantón, Chamizo, Ortega, Domingo and Almendros2012b, Reference Miralles, Trasar-Cepeda, Leiros and Gil-Sotres2013; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Miralles and Domingo2012b; Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Román, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Moro2014; Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Chamizo, Rodriguez-Caballero, Lázaro, Roncero-Ramos, Román and Solé-Benet2020; Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Moro and Cantón2021). Soil quality (Miralles-Mellado et al., Reference Miralles-Mellado, Cantón and Solé-Benet2011), aggregate stability, soil porosity and pore interconnections (Miralles-Mellado et al., Reference Miralles-Mellado, Cantón and Solé-Benet2011; Zethof et al., Reference Zethof, Bettermann, Vogel, Babin, Cammeraat, Solé-Benet, Lázaro, Luna, Nesme, Woche, Sørensen, Smalla and Kalbitz2020), as well a surface micro-topography, also increase (Rodríguez-Caballero et al., Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Cantón, Chamizo, Afana and Solé-Benet2012, Reference Rodríguez-Caballero, Aguilar, Castilla, Chamizo and Aguilar2015). Moreover, the nature and proportion of metabolites and pigments change (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Jorge-Villar, van Wesemael and Lázaro2017). The development of lichen-dominated biocrusts prevents the accumulation of metallic nutrients induced by climate change (Moreno-Jiménez et al., Reference Moreno-Jiménez, Ochoa-Hueso, Plaza, Aceña-Heras, Flagmeier, Elouali, Ochoa, Gozalo, Lázaro and Maestre2020) and regulates major P pools, increasing the resistance in the P cycle to climate change (García-Velázquez et al., Reference García-Velázquez, Gallardo, Ochoa, Gozalo, Lázaro and Maestre2022).

Similar soil physical and chemical changes have been widely reported from other locations. Belnap et al. (Reference Belnap, Prasse, Harper, Belnap and Lange2003b) showed that biocrusts increase the silt/clay fraction and the content of nitrogen, carbon and metal chelators. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Rossi, Deng, Liu, Wang, Adessi and De Philippis2014) found that the colloidal fraction of the excreted polysaccharides had a larger molecular weight and more types of monosaccharides in the older biocrusts. Felde et al. (Reference Felde, Peth, Uteau-Puschmann, Drahorad and Felix-Henningsen2014) found in the Negev that the total porosity and the pore sizes increased from cyanobacteria to lichen to moss crusts, and the pore geometry changed from tortuous to linear. Barger et al. (Reference Barger, Weber, Garcia-Pichel, Zaady, Belnap, Belnap, Weber and Büdel2016) showed that nitrogen fixation increases throughout biocrust succession. Dou et al. (Reference Dou, Xiao, Revillini and Delgado-Baquerizo2024) showed that biocrust’s capacity to increase dryland carbon stocks depends on its successional stage.

Changes in the soil-atmosphere gas exchange

In Sorbas, the net photosynthesis was two to four times greater in lichen biocrusts than in cyanobacterial crusts (Ladrón de Guevara et al., Reference Ladrón de Guevara, Lázaro, Quero, Ochoa, Gozalo, Berdugo, Uclés, Escolar and Maestre2014). In Tabernas, late and early-successional biocrusts had similar net CO2 fluxes, but photosynthesis and dark respiration rates were higher in the late-successional ones (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Ladrón de Guevara, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Ortega, van Wesemael and Cantón2018). Chamizo et al. (Reference Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero, Sánchez-Cañete, Domingo and Cantón2022) found that although CO2 efflux was mostly affected by rainfall amount and timing, it depends on the biocrust type. Distinguishing the five successional stages mentioned in Section 2, the CO2 uptake was progressively offset by the increase in respiration throughout succession (Lopez-Canfin et al., Reference Lopez-Canfin, Lázaro and Sánchez-Cañete2022a). Water vapour adsorption by dry soils was more relevant in the early stages, which has ecological implications because it is coupled with nocturnal soil CO2 uptake (Lopez-Canfin et al., Reference Lopez-Canfin, Lázaro and Sánchez-Cañete2022b).

In general, photosynthesis and respiration increase throughout succession in all drylands (Sancho et al., Reference Sancho, Belnap, Colesie, Raggio, Weber, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016b). Early-successional cyanobacterial biocrusts show lower carbon fixation values than lichen or moss biocrusts (Zaady et al., Reference Zaady, Kuhn, Wilske, Sandoval-Soto and Keselmeier2000). Garcia-Pichel and Belnap (Reference Garcia-Pichel and Belnap1996) found that physicochemical microenvironments have gas-exchange consequences within early-successional biocrust stages. Soil organic matter, which has a positive effect on soil CO2 fluxes because microbial respiration associated with its decomposition is a major component of soil respiration, also increases throughout biocrust succession (Dou et al., Reference Dou, Xiao, Revillini and Delgado-Baquerizo2024). By accelerating succession in the greenhouse (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Kong, Taylor, Le Moine, Bowker, Barber, Basler, Carbone, Hayer, Koch, Salvatore, Sonnemaker and Trilling2022), CO2 fluxes also increased from cyanobacteria to lichen and moss biocrusts.

Drought resistance and resilience

At Tabernas, the earliest cyanobacterial biocrust lost more than 50% of its cover during a prolonged in situ experimental drought. The intermediate Squamarina-Diploschistes biocrust lost almost 30%, and the latest Lepraria biocrust only lost 20% (Rubio and Lázaro, Reference Rubio and Lázaro2025).

The observed increase in drought resistance may have been related to the fact that the crusts were in a later successional stage, in which biodiversity and functional redundancy are greater, providing a greater resistance to, and resilience against, disturbance (Biggs et al., Reference Biggs, Yeager, Bolser, Bonsell, Dichiera, Hou, Keyser, Khursigara, Lu, Muth, Negrete and Erisman2020). This growing resistance to cover loss reinforces the understanding that ecosystem services increase throughout biocrust succession. This is based on findings of decreasing erodibility with succession (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Gascón and Rubio2023), increasing water collection and retention (Chamizo et al., Reference Chamizo, Cantón, Rodríguez-Caballero and Domingo2016b) and growing nutrient accumulation (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Gao, Yu, Zhang, Yan, Wu, Song and Li2022).

Macro-geomorphological effects of biocrusts

Catchment asymmetry is a global phenomenon that can occur due to several causes and is at the cutting edge of geomorphological knowledge (Langston and Tucker, Reference Langston and Tucker2018). Although it is more frequent in temperate drylands, where biocrusts can be the main soil cover, very little is known about the effect of biocrusts on these processes. However, Churchill (Reference Churchill1981) found in the Badlands National Park catchments, having the pole-oriented hillslopes less steep; according to Figure 4 in that research, the northern slopes have biocrusts in the upper half, whereas the southern slopes do not.

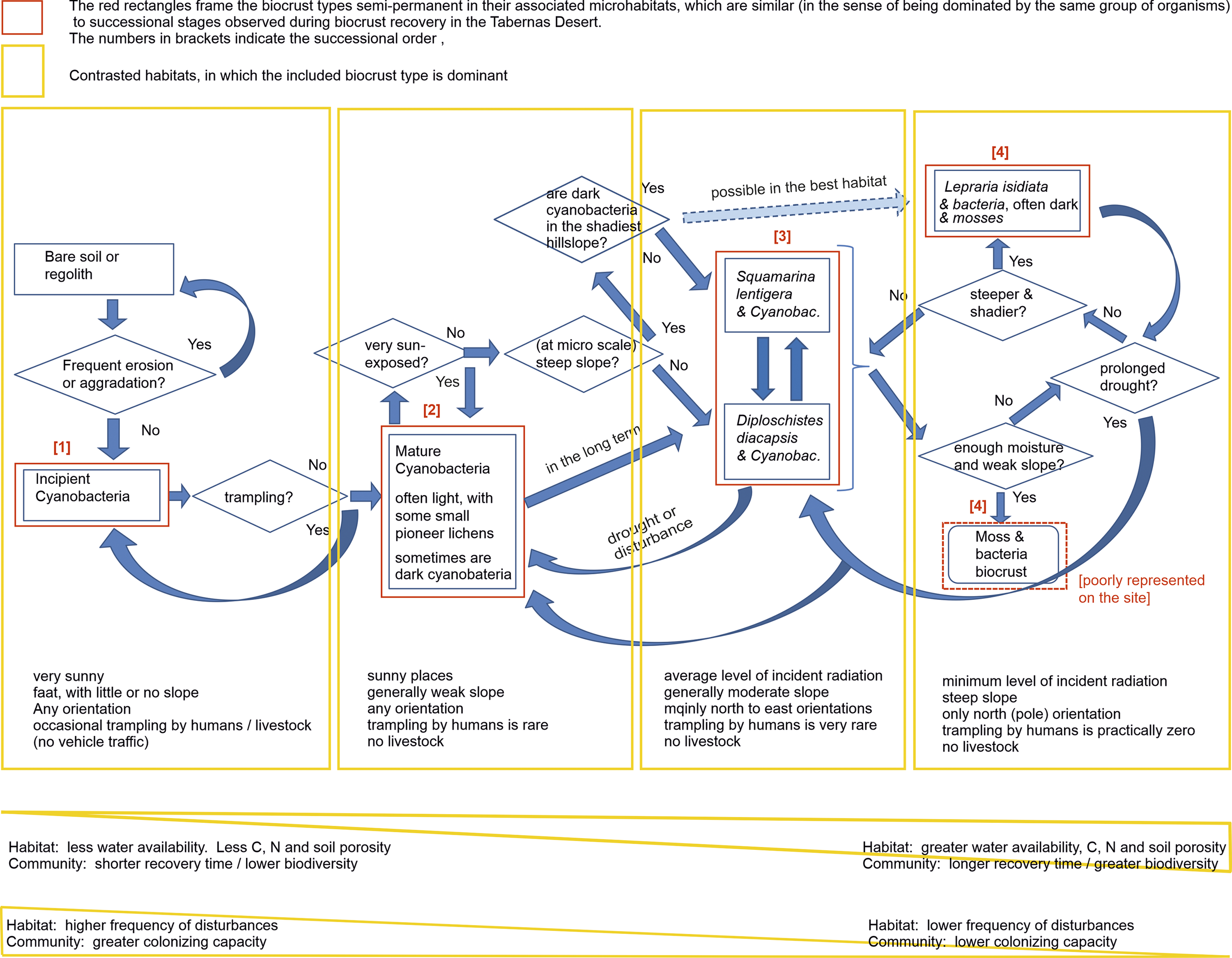

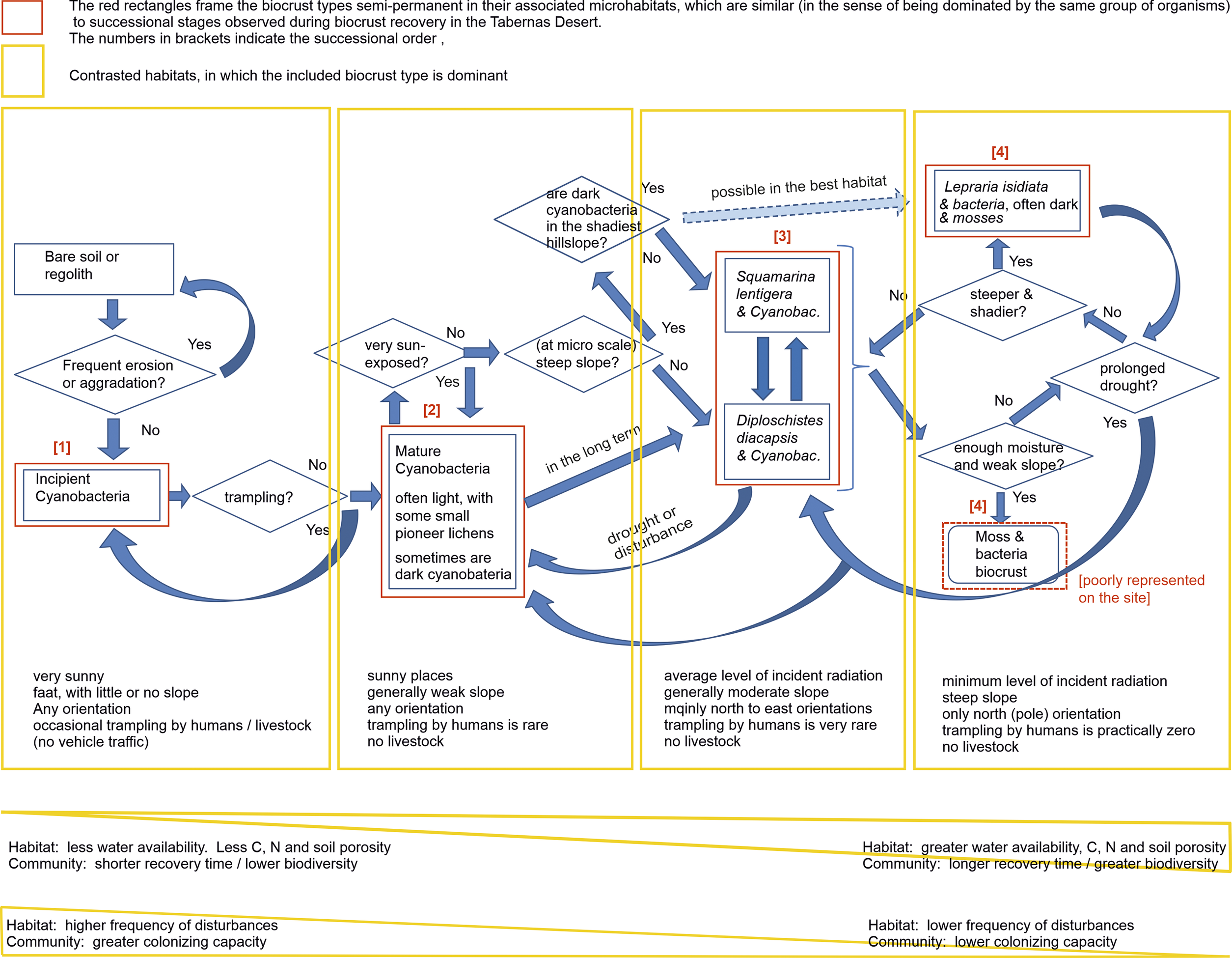

Figure 4. Conceptual model of biocrust succession for the Tabernas Desert, southeast Spain. Only the biocrust types distinguishable by the naked eye are included. The model relates each type of biocrust/successional stage to the habitat in which it dominates. Straight arrows indicate progressive succession. In each habitat, you can see the succession up to the dominant type in that habitat; thus, the complete succession can only be seen in the most favourable habitats for lichen biocrusts. Curved arrows indicate regressive succession. The arrow with broken lines and a less intense colour indicates that such progress is possible, although it does not always occur.

At Tabernas, we analysed more than 6,400 catchments, very often finding catchment asymmetry. This asymmetry occurs because one of the two hillslopes draining into the same channel is more stable, and the channel mainly undermines the opposite hillslope, which progressively becomes steeper. Biocrusts are stabilizing forces and develop better in the shadier hillslopes. In most asymmetries, the most stable hillslope was the shadier one, which was the best for the progress of biocrust succession. Therefore, although the effect of cyanobacteria stabilizing soil is well known, the known larger stabilizing capacity of lichens seems great enough for feedback catchment asymmetry (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Calvo-Cases, Rodriguez-Caballero, Arnau-Rosalén, Alexander, Rubio, Cantón, Solé-Benet and Puigdefábregas2022).

Other indirect approaches to biocrust succession are in the Supplementary Material.

Microhabitat control over crust types

The association between microhabitats and biocrust types observed for decades in Tabernas was verified by Rodriguez-Caballero et al. (Reference Roncero-Ramos, Román, Rodríguez-Caballero, Chamizo, Águila-Carricondo, Mateo and Cantón2019b), who claimed that terrain attributes, such as slope and potential incoming solar radiation, are the main drivers of the distribution of biocrust types. Cyanobacteria dominate in stable zones with high solar radiation because they produce photo-protective pigments (Miralles et al., Reference Miralles, Jorge-Villar, van Wesemael and Lázaro2017). Lichens cover mainly the upper half of the shadier north-oriented hillslopes because they are often outcompeted by vegetation on the footslopes.

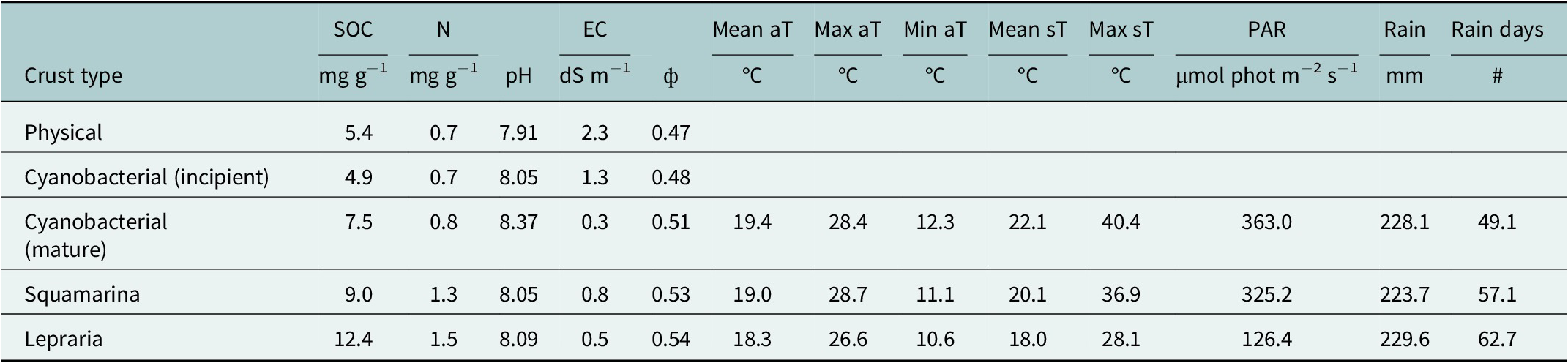

Successional trends were apparent for soil features of microhabitats corresponding to different crust types, and microclimatic variables at stations in Incipient and Mature cyanobacteria, Squamarina and Diploschistes and Lepraria (Table 1). These trends were particularly apparent in soil organic carbon and nitrogen, soil porosity, soil temperatures, photosynthetically active radiation and the number of days with at least one record in the rain gauge.

Table 1. Soil properties are averages of five replicates sampled in typical crust-type sites, from Lopez-Canfin et al. (Reference Lopez-Canfin, Lázaro and Sánchez-Cañete2022a)

Note: The microclimatic variables are the averages of the yearly values of the 2004–2021 period. Mean aT, Max aT and Min aT are mean, maximum and minimum air temperatures, respectively. Mean sT and Max sT are mean and maximum temperatures at the soil surface, respectively. Rain is the average of the yearly total rainfall volume. N Rain d is the number of days with at least one record in the rain gauge, which is likely related to a larger number of non-rainfall water inputs in the more shady habitats, as rainfall is similar across these habitats.

Abbreviations: SOC, soil organic carbon; N, nitrogen; EC, electrical conductivity; PAR, photosynthetically active radiation; ф, soil porosity.

The control of microclimate and soil properties on biocrust types has been found in various other drylands (Lan et al., Reference Lan, Wu, Zhang and Hu2012; Kidron, Reference Kidron2019; Navas Romero et al., Reference Navas Romero, Herrera Moratt, Martinez, Rodriguez and Vento2020; Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024). However, soil properties change over time with community development, which could make the soil more suitable for more competitive biocrust types. According to Colesie et al. (Reference Colesie, Scheu, Green, Weber, Wirth and Büdel2012), this is precisely at the core of the successional process. Thus, microclimate would be the main driver of the microhabitat effect because most of the differences in soil may not be an abiotic factor but rather due to succession. Arias-Real et al. (Reference Arias-Real, Delgado-Baquerizo, Sabater, Gutiérrez-Cánovas, Valencia, Aragón, Cantón, Datry, Giordani, Medina, de los Ríos, Romaní, Weber and Hurtado2024) found that microhabitat and succession are closely related, and water availability can be the core driver of biodiversity and functional patterns. Thus, microhabitat acts simultaneously with succession, controlling the speed of succession, consistent with Felde et al. (Reference Felde, Rodriguez-Caballero, Chamizo, Rossi, Uteau, Peth, Keck, De Philippis, Belnap and Eldridge2020). Further, the duration of moisture in the topsoil can often be the main driver of biocrust type (Kidron, Reference Kidron2019; Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024). However, the existence of poorly understood factors highlighted in Sorbas suggests that it is better to invoke microhabitat rather than water content as the causal agent of these changes.

Synthesis

Our results as a whole

At Tabernas, in relatively shady habitats where lichens can develop, they replace cyanobacteria (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008; Rubio and Lázaro, Reference Rubio and Lázaro2023), confirmed by our results in Sorbas and the soil micro-profiles. These changes in the crust type are due to succession because they occur over time within certain microclimates. The crust types of the recovery phases were similar to those dominating in the different microclimates. This allowed us to accept the space-for-time samplings for the indirect studies. Thus, the changes in various structural and functional biocrust properties according to the biocrust type were related to succession because they varied consistently with the hypothetical succession pathway. The results of these indirect studies, in themselves, do not imply species replacement, which was demonstrated by direct research. Indirect research provided information on those functional changes that might be due to the successional process, consistent with Garcia-Pichel et al. (Reference Garcia-Pichel, Felde, Drahorad, Weber, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016). These changes in properties over time trend towards a more stable, structured and fertile soil, which one would expect for succession progress.

Initially, we had identified two challenges to accept that succession can configure the crust types: (i) the verified association between crust types and microclimates, and (ii) the persistence of cyanobacterial biocrusts in some sites. Both facts suggest that the microclimate is the main driver of biocrust type. In each microhabitat, in the absence of disturbances or long drought, the corresponding biocrust type can be permanent at the human time scale (Kidron and Xiao, Reference Kidron and Xiao2024). However, after a disturbance, succession will occur in the relatively shady habitats where the microclimate allows for lichen development, and not (or very slowly) in the more exposed habitats where cyanobacteria can remain dominant for a long time. Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016b) and Felde et al. (Reference Felde, Rodriguez-Caballero, Chamizo, Rossi, Uteau, Peth, Keck, De Philippis, Belnap and Eldridge2020) suggest that water availability can determine the successional endpoint. All crust types undergo succession, but succession does not occur in some places because of habitat constraints. Succession can also be seen in soft ecotones (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Cantón, Solé-Benet, Bevan, Alexander, Sancho and Puigdefábregas2008) because of climatic oscillations.

We concur with Kidron and Xiao (Reference Kidron and Xiao2024) that the multiple functions and features of cyanobacteria (reviewed above) do not necessarily imply the development of lichens or mosses. This occurs because such development may be limited by microhabitat, but that does not contradict that succession can shape crust types.

Although the factors controlling crust type (vegetation, radiation, geomorphology and soil; Bowker et al., Reference Bowker, Belnap, Büdel, Sannier, Pietrasiak, Eldridge, Rivera-Aguilar, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016) are similar at intermediate (m1-m2) and micro (m−2-m−3) scales, changes at Tabernas seem much slower at intermediate scales (sensu Mallen-Cooper et al., Reference Mallen-Cooper, Cornwell, Slavich, Sabot, Xirocostas and Eldridge2023). Our ongoing research suggests that this is due to microscale changes spatially offsetting each other, but also to lower spatial resolution in data at larger scales.

Successional model integrating microclimate

The conceptual model in Figure 4 synthesizes our understanding of the biocrust distribution and dynamics at Tabernas.

Cyanobacterial biocrusts constitute a widespread matrix on which lichen biocrusts eventually develop. In the sunniest and eventually trampled areas, this biocrust remains for decades in an incipient developmental stage. The cessation of trampling gives rise to mature cyanobacteria, including light cyanobacteria everywhere and dark cyanobacteria that were only dominant in the early recovery stages of the shadiest plots. Cyanobacteria produce significant physical and chemical changes in the soil (Cantón et al., Reference Cantón, Chamizo, Rodriguez-Caballero, Lázaro, Roncero-Ramos, Román and Solé-Benet2020), facilitating lichen biocrusts. Cyanobacteria dominate in the sunniest areas (35 years of observation), although, in the long term, they share dominance with lichens, as can be observed in the oldest geomorphological levels of the drainage network (Lázaro et al., Reference Lázaro, Alexander, Puigdefábregas, Alexander and Millington2000). In shadier sites, the cyanobacterial biocrust is replaced by lichens of the Squamarina-Diploschistes community within about 15–20 years (Rubio and Lázaro, Reference Rubio and Lázaro2023). The Lepraria community is the latest stage because it develops more slowly, and many species of the previous stages appear during such a process (Rubio and Lázaro, Reference Rubio and Lázaro2023). In the shadiest sites, mature dark cyanobacteria could (experiment ongoing) sometimes slowly generate a Lepraria community, skipping the Squamarina-Diploschistes stage. Mosses only form metric-scale patches in Sorbas during wet winters. Disturbances, such as prolonged droughts, can reverse the direction of succession, further receding with more intense or long-lasting disturbances, consistent with our data from Sorbas and Rubio and Lázaro (Reference Rubio and Lázaro2025).

This model is consistent with previous knowledge. Because cyanobacteria are autotrophs and among the oldest organisms on Earth (Weber et al., Reference Weber, Belnap, Büdel, Belnap, Weber and Büdel2016a), they can be the first colonizers. The first would be filamentous bundle-forming cyanobacteria that move upwards when hydrated and downwards when desiccating, spreading their exopolysaccharides (Belnap et al., Reference Belnap, Büdel, Lange, Belnap and Lange2003a; Zhang, Reference Zhang2005), which stabilize soil (Roncero-Ramos et al., Reference Roncero-Ramos, Román, Rodríguez-Caballero, Chamizo, Águila-Carricondo, Mateo and Cantón2019b). Later, less mobile unicellular or heterocystous cyanobacteria appear, together with green algae (Belnap and Eldridge, Reference Belnap, Eldridge, Belnap and Lange2003; Garcia-Pichel et al., Reference Garcia-Pichel, Johnson, Yougkin and Belnap2003; Sorochkina et al., Reference Sorochkina, Velasco Ayuso and Garcia-Pichel2018) when the surface is not degraded (Roncero-Ramos et al., Reference Roncero-Ramos, Muñoz-Martín, Cantón, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Mateo2020). Pioneer lichens follow, gradually followed by other species of lichens and mosses (Belnap and Eldridge, Reference Belnap, Eldridge, Belnap and Lange2003; Lan et al., Reference Lan, Wu, Zhang and Hu2012). The fact that lichens replace cyanobacteria is consistent with the aspect preferences found by Bowker et al. (Reference Bowker, Belnap, Davidson and Goldstein2006), irrespective of the spatial scale. The successional order is consistent with the accelerating succession in greenhouse results from Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Kong, Taylor, Le Moine, Bowker, Barber, Basler, Carbone, Hayer, Koch, Salvatore, Sonnemaker and Trilling2022). Regressive succession was noticed in other areas (Zelikova et al., Reference Zelikova, Housman, Grote, Neher and Belnap2012). The occasional splitting of succession (following different pathways in different microhabitats) replicates in microhabitats at the local scale the fact that different global habitats can have specific successional sequences (Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Bowker, Zhang, Belnap, Weber, Büdel and Belnap2016b).

It is noteworthy that our model only deals with the crust types easily recognizable in situ by the naked eye. Interestingly, bundle-forming cyanobacteria dominate the Incipient type, whereas unicellular cyanobacteria dominate in the Mature type (Roncero-Ramos et al., Reference Roncero-Ramos, Muñoz-Martín, Cantón, Chamizo, Rodríguez-Caballero and Mateo2020).

Conclusion

In the Tabernas region, biocrust types of different successional stages are often the same as those associated with different microclimates. The successional pathway may split and regress. Our model, consistent with previous knowledge, includes two earlier stages of cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts (Incipient and Mature) and two later stages of lichen biocrusts (Squamarina-Diploschistes, Lepraria). Each stage corresponds to a habitat, from the most sun-exposed and trampled surfaces (old pathways) to the shadiest and best preserved biocrusts. Our model considers the order in which species tend to appear due to their requirements and interspecific relationships. It clarifies how microclimate and succession interact to shape biocrust type. Biocrust composition is necessarily in equilibrium with the microhabitat, as well as with biotic factors such as facilitation or competition. Consequently, succession occurs at very different speeds across space. In the moistest habitats, all the stages will develop. In the driest, at human time scales, the biocrust will remain dominated by cyanobacteria. Therefore, any biocrust type can seem permanent because each microhabitat will display the most advanced crust type it can support. Thus, succession can be observed in moist habitats after biocrust disturbance, and in ecotones because of climate oscillations.

Our results show that space-for-time sampling in biocrusts is feasible. To verify and exploit this on a global scale would facilitate the research on biocrust dynamics and functionality, which is important in drylands.

Open peer review

For open peer review materials, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10009.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/dry.2025.10009.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Domingo Álvarez Gómez, technician of the geomorphology laboratory of our institute, for his meticulous help with the micro-profile sections in samples of unaltered biocrusted soil. The authors also thank Lydia N. Bailey, biologist at the Fort Collins Science Center, for her question on the scale during our talk at the Biocrust 5 Conference, which gave rise to this article.

The authors would like to express special thanks to the Viciana brothers, landowners of the El Cautivo field site, where they carried out most of these investigations, as well as to Lindy Whals and Francisco Contreras, owner and manager of the Sorbas farm where the experiments are located.

Author contribution

RL conceived and designed the article, obtained and processed data, interpreted results, wrote the first draft and provided most of the funding. CR and CLC collaborated in several field campaigns, elaborated data and published some of the most recent articles on which this article is based. BRR contributed to the article’s design and provided most of the literature review. All authors discussed the interpretation of the results and reviewed the writing of the final version.

Financial support

This study was supported by the research projects DINCOS (CGL2016-78075-P) and INTEGRATYON3 (PID2020-117825GB-C21 and C22), both funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, along with the European ERDF funds, as well as the BAGAMET (P20_00016) and PCBio (CA32507) projects, funded by the Andalusian Plan for Research, Development and Innovation (PAIDI-2020) and Andalusia’s Complementary Plans for Biodiversity, respectively, of the Junta de Andalucía. The Consuelo Rubio’s predoctoral student contract FPU18/00035 and the Clement Lopez’s postdoctoral Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement number 101109110 also facilitated this work. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union (EU) or the European Research Executive Agency (REA). Beatriz Roncero-Ramos was supported by the Junta de Andalucía (PAIDI-DOCTOR 21_00571).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No accompanying comment.