Introduction

Political representation is one of the most fundamental elements of democracy. It is the way to realize the core democratic idea of the people's sovereignty (Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2020). Nevertheless, the nature of such representation is often paradoxical, especially between elections (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam, Persson, Narud and Esaiasson2013). Given that representatives cannot act in congruence with the positions of all citizens at all times, tensions in the relationship between representatives and the represented are inherent, leading to various representational deficits or failures (Dovi, Reference Dovi and Zalta2018; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Powell, Reference Powell2004).

Further hampering the legislators’ ability to promote policies that accord with the desires of their constituents is the multiplicity of principals to whom the legislators are committed. When making policy decisions, legislators usually face multiple pressures: the preferred policies of their constituents or a specific group they wish to represent and, the mandates of their party leadership, to name two such principals. Moreover, legislators' own moral convictions, or conscience, can also provide possible fraction points. This notion has been emphasized by the trustee model of representation (Burke, Reference Burke and Kramnick1774, cited in Kramnick, Reference Burke and Kramnick1999), which posits that representatives should, and often do, consider their own conscience when determining the best course of action for their constituents. Inasmuch as (some of) these principals' preferences are not aligned, legislators face conflicting demands (Carey, Reference Carey2007, Reference Carey2009; Umit & Auel, Reference Umit and Auel2020). When we take into account the plethora of principals to whom legislators are committed, it becomes evident that legislators simply cannot be responsive to all principals at all times, at least in terms of policy adaptation.

From an instrumental point of view, legislators who fail to demonstrate responsiveness or congruence often face electoral sanctions which hinder their re‐election prospects (Arnold & Franklin, Reference Arnold and Franklin2012, but see Hanretty et al., Reference Hanretty, Mellon and English2021 for a different perspective). Indeed, recent research by Dassonneville et al. (Reference Dassonneville, Blais, Sevi and Daoust2021) underscores that, when confronted with varying perceptions of representation, a majority of citizens uphold the notion that representation entails voting in accordance with the majority opinion of their constituency. Nevertheless, legislators are also driven by non‐instrumental motivations to be responsive to citizens, including the fulfilment of the role of a ‘good’ representative (Dovi, Reference Dovi2012) and other advantages linked to upholding democratic values and norms (Esaiasson & Wlezien, Reference Esaiasson and Wlezien2017).

Responsiveness, traditionally understood as a bottom‐up process in which legislators adapt their actions on policy to match the preferences of the majority of citizens,Footnote 1 can be viewed also as a dynamic, communicative and top‐down process (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam, Persson, Narud and Esaiasson2013, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). Communicative responsiveness is regarded as a method of garnering voter support even when the policies the legislators are promoting do not accord with those favoured by their constituents. It allows legislators to avoid the blame and electoral sanctions that voters may impose on them due to the failure to promote the policies the latter favour. Thus, representatives have other measures by which they can demonstrate their responsiveness to their voters. Examples include the legislators' ability to inform themselves regarding the preferences and wishes of their voters (‘listen’), and their ability to explain and justify their actions (‘explain’) (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). Such measures can be most effective in counteracting the negative effects of incongruent policy actions (Grose et al., Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015).

Conceptualizing responsiveness as a communicative process calls for a theoretical and empirical exploration of the various ways in which legislators can be responsive to their principals as well as their effectiveness in doing so. While this line of research is growing, not enough is known about how representatives communicate their actions to their voters, and the effect of such communications on voters. Our study contributes to this ongoing discussion. Specifically, we ask, first, do legislators seek to re‐establish themselves as responsive if they vote for a policy their constituents do not favour? Second, if so, what rhetorical measures do they adopt in order to do so? Third, what factors affect their likelihood of using this approach?

We join the bourgeoning literature studying legislative explanations (Broockman & Butler, Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam, Persson, Narud and Esaiasson2013, Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017; Grose et al., Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015; McGraw et al., Reference McGraw, Best and Timpone1995; Minozzi et al., Reference Minozzi, Neblo, Esterling and Lazer2015) and legislators' communicative responsiveness (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). In this study, we focus on legislators' use of explanations in the context of a representational deficit. We propose the concept of rhetorical responsiveness, which refers to legislators' use of compensatory speech acts to deal with their support for policies their constituents do not necessarily favour. Adapting Aristotle's (Reference Robert2019) three modes of persuasion – ethos, logos and pathos Footnote 2 to our compensation framework – we show that legislators compensate principals who hold positions that are incongruent with the legislators’ votes by offering them material or symbolic benefits to counterbalance the latter's incongruent voting (exchange), reinterpreting the principals’ preferences to fit the legislators’ actions on policy ((re)interpretation) or adopting their point of view (perspective taking).

Using the Brexit referendum as an illustrative case, we examine the parliamentary behaviour and discourse of cross‐pressured legislators in the House of Commons. Unlike studies that have examined legislators' communications with individual voters (Grose et al., Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015) or small groups of voters (Minozzi et al., Reference Minozzi, Neblo, Esterling and Lazer2015), we utilize data on legislators’ parliamentary speeches to explore whether legislators choose to use strategies related to rhetorical responsiveness in their public speaking time in parliament. We also investigate the types of rhetorical compensation they provide and to whom.

We first demonstrate how legislators' representational deficits vis‐à‐vis their constituencies arose between 2017 and 2019 with regard to the parliamentary discussions on Brexit. We show the complexity of the situation legislators endured as a result of the Brexit referendum and the following parliamentary discussions (Aidt et al., Reference Aidt, Grey and Savu2021) and demonstrate that the legislators' policy actions made it impossible for at least some of them to appear to be responsive to the demands of their constituencies regarding this vote. Next, we explore the rhetorical patterns in the legislators’ speeches and demonstrate that legislators use rhetoric in lieu of policy adaptation: they pay more attention to those who oppose the policy they voted for in an attempt to compensate them rhetorically.

In our main empirical analysis, we combine the traditional view of responsiveness – focused on policy actions – and the more recent communicative view of responsiveness – focused on legislators' explanations – to show how the two interact. Analysing legislators' rhetorical responsiveness as a function of the size of the representational deficit with regard to policy, we show that the larger the gap is between the legislators’ policy actions and the preferences of their constituency, the more likely they are to use exchange or perspective taking acts to compensate for their actions and as a form of rhetorical responsiveness. In contrast, for (re)interpretation, the opposite is true. Our findings attest to the role of parliamentary speech in re‐establishing and maintaining the image of the legislator as responsive to her constituents. The upshot is a richer, more nuanced understanding of the representational relationship and its underlying mechanisms.

The role of explanations: Theoretical arguments

The role of explanations in representation has recently received growing attention (Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2020). However, its roots can be found in Hannah Pitkin's (Reference Pitkin1967) seminal book in which she famously claims that representatives should not act incongruently with their voters, without a good reason and a good explanation. Fenno's (Reference Fenno1978) classic work echoes this point by noting that explanations are an important part of legislators' home style. Explanations are a strong tool in the legislators' toolbox because they enable legislators to shape public opinion, not just reflect it (Disch, Reference Disch2011; Jacobs & Shapiro, Reference Jacobs and Shapiro2000; Mansbridge, Reference Mansbridge2003; Pitkin, Reference Pitkin1967; Urbinati, Reference Urbinati2006). Explanations may also help legislators persuade voters that they are indeed working to promote their policy interests (McGraw et al., Reference McGraw, Timpone and Bruck1993).

The limited yet growing empirical work on legislators' use of explanations suggests that they are a very popular and effective tool. Grose et al. (Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015) show that US senators tailor their explanations to their principals, compensating for incongruent policy positions. They also report that such explanations are extremely effective in shaping voters' perceptions of the senator's policy positions and their general attitude towards the senator. Relatedly, Minozzi et al. (Reference Minozzi, Neblo, Esterling and Lazer2015) find that legislators' substantive persuasion – defined as persuasion meant to change attitudes about an issue – affects voters' positions on specific policy issues. It also influences the degree of trust in and approval of the legislator and the likelihood of voting for her. McGraw et al. (Reference McGraw, Best and Timpone1995) also establish that explanations have a singular effect distinct from that of policy outcomes on the evaluation of the representative and the policy. Esaiasson et al. (Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017) maintain that representative actions defined as ‘explaining’ and ‘listening’ are more effective than those defined as ‘adapting’, signalling the importance of communication between voters and legislators in representational relationships. In addition to these benefits, prior literature shows that explanations can be effective in helping legislators avoid blame (Levendusky & Horowitz, Reference Levendusky and Horowitz2012; McGraw, Reference McGraw, Kuklinski and Denis2001; Robison, Reference Robison2017). However, Robison (Reference Robison2022) indicates that this option is very limited in scenarios in which rival accounts challenge the explanation's sincerity or credibility. We now turn to present our theoretical expectations regarding legislators' use of explanations in the context of a representational deficit.

Discursive attention in lieu of policy congruence

We begin with a basic expectation regarding the relationship between representational deficits and legislators' use of their speaking time in parliament. When legislators fail to act according to their constituencies' policy preferences, they are in a representational deficit. In such situations we expect them to devote more discursive attention to their constituency, compared to situations in which no representational deficit arises. Such attention can help them smooth over the negative consequences of their policy incongruence. This expectation is in line with the literature and consistent with previous studies (e.g., Umit & Auel, Reference Umit and Auel2020). Hence, our first hypothesis states that

H1: Legislators who are in a representational deficit with their constituency will devote more discursive attention to it in their floor speeches, compared to legislators who are not in a representational deficit with their constituency.

Rhetorical responsiveness: Compensating through speech

Legislators who are in a representational deficit may devote more discursive attention to their constituencies. However, what does such attention entail? We argue that for legislators who are in a representational deficit, the attention given to their constituency should be conceptualized as rhetorical responsiveness, defined above as the responsiveness attained through compensatory speech acts designed to make up for a lack of policy congruence. Compensatory speech acts can thus be seen as a substitute for legislators’ incongruent policy actions. We use the term ‘compensation’ because such explanations are meant to make up for a lack of policy adaptation. We identify three types of compensatory strategies legislators use to maintain their rhetorical responsiveness and persuade their constituencies that they are indeed responsive to them. We anchor our classification in Aristotle's (Reference Robert2019) three modes of persuasion: logos, ethos and pathos. Importantly, the three rhetorical strategies are not mutually exclusive. Legislators can use them simultaneously and the use of one rhetorical strategy does not induce or prevent the use of another.Footnote 3

(Re)interpretation is a rhetorical strategy in which the speaker uses rhetoric in order to decrease the perceived representational deficit. We regard reinterpretation as an argumentative means and, therefore, consistent with Aristotle's logos. Reducing the deficit is performed by closing the alleged gap between the speaker and the principal. The representative frames and interprets the principal's position as aligned with her own, claiming that in fact her actions on policy are not so different from the principal's preferences. The idea of reinterpretation echoes Saward's (Reference Saward2010) work on the ‘constructivist turn’ in the study of representation, according to which representatives engage in claim‐making in order to discursively construct the principals they wish to represent.

Here is an example. Emma Reynolds – a Labour MP whose constituency's aggregate position on the Brexit vote was overwhelmingly pro‐Leave (67.7 per cent) – nevertheless, voted against Theresa May's withdrawal agreement, claiming it was not what her constituents voted for and would not be in their best interests. She stated, ‘The people did not vote in the 2016 referendum to be poorer, and I cannot in all conscience vote for a deal that makes my constituents poorer and the country less safe’ (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2019).

Exchange is a rhetorical strategy in which the speaker highlights the material or the symbolic benefits that she has already provided to the principal or plans to do so.Footnote 4 Notably, these benefits are not necessarily tied to the same issue that gave rise to the deficit, allowing legislators to reference unrelated benefits extended to their constituents. This resonates with Grimmer's research (Reference Grimmer2013) on the US Congress, which highlights how representatives employ communication concerning the distribution of material benefits to offset policy incongruence. Additionally, it aligns with Eulau and Karps’ (Reference Eulau and Karps1977) conceptual framework of allocation responsiveness, which centres on the representative's endeavours to offer benefits to their constituency. Embedded in the notion of ethos, this rhetorical strategy presents a form of quid‐pro‐quo argument that revolves around the speaker and hinges on their performance: Right now you feel you are not represented, but look what you are getting in return! An example of this rhetoric is the statement of Labour MP Caroline Flint when addressing those who favoured remaining in the European Union. In an attempt to make up for voting for a policy her constituents opposed, Flint focused on the benefits she had provided them when shaping the exit deal, namely, ‘the things you and I value most’. She went on to say:

We will regain control of our laws and borders. To remain supporters, whom I stood alongside in 2016, I want to say, Yes, we respected the decision to leave, but we have successfully protected the things that you and I value most: open trade with the European Union (EU), workers' rights, high environmental standards, rights for Brits abroad, respect for EU citizens working here, student exchange programmes, joint research projects – I could go on. All of that can be secured, but only with a deal (Flint, Reference Flint2019).

Perspective taking is a strategy whereby the speaker acknowledges the perspective of those left unrepresented and includes it in the conversation. The legislator addresses their grievances, concerns or distress. Directed towards the listener's point of view, this strategy aligns with the idea of pathos. It emphasizes the audience's perspective as a method for appealing to its emotions, interests and views. Perspective taking is considered a strategy of rhetorical compensation because it makes the preferences of policy losers present and acknowledged in the conversation. By doing so, it provides representation for such preferences, even if they are not promoted into policy. The compensation lies in that policy losers' voices are heard and acknowledged by the representative in parliament and are not simply ignored (Easton, Reference Easton1965). This understanding of compensation resonates with perspectives of responsiveness which stress how important it is for voters to have their representative be informed about their wishes and views (Butler, Reference Butler2014; Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017; Jacobs & Shapiro, Reference Jacobs and Shapiro2000). By addressing the preferences of policy losers the representative signals to her constituents that she indeed hears them and is emphatic to the discomfort they may feel by her support of a different policy than the one they had preferred. While it is true that constituents are still bound to be disappointed by not having their preferred policy promoted, it is reasonable to assume that they will be appreciative of the legislator's acknowledgment of their existence, preferences and grievance's when speaking in the plenary, instead of just bluntly ignoring such preferences.

For example, Conservative MP Craig Tracey, who supported the Brexit deal in opposition to his constituents’ Remain vote, highlighted the two most important criteria for his constituents in judging any deal. By doing so he took his constituents' perspective and articulated it in public debate. He said, ‘I was keen to see an agreement delivered that I could support. Critically, the one on offer does not meet two of the criteria set out by my constituents: the return of our sovereignty and the ability to trade freely’ (Tracey, Reference Tracey2019). Note that despite the concerns he raised, in his policy actions he went against his constituents' position, 67 per cent of whom voted to remain and supported the deal. Thus, taking the perspective of the constituents is used as a compensatory rhetorical strategy to demonstrate his responsiveness despite his vote.

The size of the representational deficit and its effect on rhetorical responsiveness

In our next hypotheses, we combine the traditional view of responsiveness – focused on policy actions – and the more recent communicative view of the term – focused on legislators' explanations – to show how the two interact. For this purpose, we consider how legislators' rhetorical responsiveness is expected to change as a function of the magnitude of the representational deficit, in terms of policy adaptation. While it is possible to treat representational deficits as binary, a more nuanced approach would consider them as a matter of degree. Thus, a sizable representational deficit would occur if constituents' aggregate preferences lean significantly in one direction and are ignored, policy wise, by the legislator, whereas in constituencies with aggregate preferences less tilted towards one policy alternative or another, smaller representational deficits would occur. This degree reflects the number of ‘policy losers’ the legislator fails to represent in terms of policy and therefore may want to compensate rhetorically.

It should be noted that this definition is insensitive to the saliency individual voters attribute to their preference regarding policy issues. Having 70 per cent of voters in a constituency support a given policy says nothing about how much each individual voter cares about that policy. However, it does provide an important indicator for the aggregate preference of the constituency, thus affecting the behaviour of legislators.Footnote 5 Legislators are attuned and aware of the aggregate preference of their constituency on policy issues and tend to take it into account. Anecdotal evidence for this can be found in our textual corpus, where many MPs reiterate their constituency's aggregate Brexit preference in their floor speeches. For example: ‘It is no secret that I voted to leave the EU, as did 67 per cent of my constituents’ (Tracey, Reference Tracey2019); ‘In my constituency, there was a 70% vote to leave’ (Vickers, Reference Vickers2019); ‘I personally voted to remain, and have always been conscious of the fact that a majority of my constituents – 57.3% – voted to remain, while recognizing and remembering that over 40%, a significant minority, voted to leave’ (Robinson, Reference Robinson2019).

Using the Brexit vote, we investigate the effect of the size of a representational deficit on the legislator's choice of compensatory rhetorical strategy. Our basic premise is that the greater the representational deficit, that is, the gap between the constituency's aggregate policy preferences and the legislator's voting behaviour, the more likely that legislators will engage in rhetorical responsiveness to compensate their constituents. In other words, the greater the loss in terms of policy responsiveness (and the greater is the number of policy losers), the stronger the legislators’ incentive to engage in rhetorical responsiveness. For example, in a constituency where 70 per cent voted Remain and the legislator supported Theresa May's exit plan, the legislator would be more likely to engage in rhetorical responsiveness than in a similar scenario but with a smaller proportion, say, 55 per cent.

This rationale rests on two main reasons. When representational deficits are large, legislators (1) are better informed about voters' preferences and (2) face greater incentives to demonstrate responsiveness to their voters, especially those disappointed by the legislators' policy choices. We now elaborate on these reasons.

Effective compensation requires that the legislator be informed of and able to assess constituents' attitudes and the existence of a representational deficit. In and of itself, this is not a trivial task, though it bears extreme significance to democratic representation and policymaking. For legislators to consciously embrace the policy preferences of citizens (Soroka & Wlezien, Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010), or offer valid justifications when they deviate from them (Jacobs & Shapiro, Reference Jacobs and Shapiro2000), they must possess a clear comprehension of the prevailing public sentiment. Indeed, according to Stimson et al. (Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995), rational politicians are adept at gauging the national sentiment and adjusting their actions accordingly and Mansbridge's (Reference Mansbridge2003) concept of ‘anticipatory representation’ centres on representatives' ability to grasp the public's preferences and anticipate their needs.

Moreover, the context of intense competition within which politicians function (Sheffer et al., Reference Sheffer, Loewen, Soroka, Walgrave and Sheafer2018), their primary drive for re‐election (Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1974) and the personality characteristics often displayed by politicians (Best, Reference Best2011) should collectively position them as adept assessors of public opinion (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans, Soontjens, Pilet, Brack, Varone, Helfer, Vliegenthart, van der Meer, Breunig, Bailer, Sheffer and Loewen2023). Their motivations are aligned with understanding and responding to the desires of the populace. This connects to recent literature on how representatives process information and its effect on their behaviour (Butler, Reference Butler2014; Butler & Nickerson, Reference Butler and Nickerson2011; Öhberg & Naurin, Reference Öhberg and Naurin2016; Richardson & John, Reference Richardson and John2012). Nevertheless, a recent study based on a large‐scale comparative survey by Walgrave et al. (Reference Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans, Soontjens, Pilet, Brack, Varone, Helfer, Vliegenthart, van der Meer, Breunig, Bailer, Sheffer and Loewen2023) show that more often than not legislators are quite inaccurate in estimating the public's preferences. We argue that legislators' ability to evaluate the public's preferences is contingent on the magnitude and uniformity of the aggregate preferences: the more crystalized the aggregate preference of the constituency, the more likely the legislator is to correctly evaluate what that preference is. Therefore, as the representational deficit grows larger, legislators are more likely to use discursive strategies of rhetorical responsiveness – simply because they are more likely to accurately gauge the aggregative preference of their constituency and, as a result, be aware of the existence of representational deficit.

But once aware of a deficit, what incentivizes legislators to use discursive compensational strategies the larger it is? This brings us to the second part of the argument, which rests on legislators' incentives for re‐election (Mayhew, Reference Mayhew1974) and on the responsiveness–acceptance connection (Esaiasson et al., Reference Esaiasson, Gilljam and Persson2017). As we noted earlier, responsiveness is often thought of as a means for legislators to elude voter sanctions when failing to vote in accordance with voters' preferences. Studies have shown that when legislators behave in a manner that persuades voters that their desires and perspectives have been considered, voters experience greater ease in overcoming dissatisfaction stemming from policy choices that are not in their favour. In the terminology of this study, when legislators discursively compensate incongruent voters they signal their voters that they are not being ‘neglected or ignored’ and, by doing so, they ‘help to reduce frustrations and discontent and thereby either prevent the withdrawal of support or positively stimulate it’ (Easton, Reference Easton1965, p. 433).

Thus, legislators engage in responsiveness to avoid blame and maintain their chances for re‐election. Fearing potential electoral consequences, legislators proactively monitor public opinion, allocating substantial resources to fully comprehend it and pre‐emptively avoid electoral backlash (Stimson et al., Reference Stimson, MacKuen and Erikson1995). When voters' preferences are more crystalized and cohesive, there is a stronger pressure for accountability, and therefore in the event of a representational deficit, the need for compensation rises. Put differently, as the representational deficit grows larger – meaning that the aggregate preference of the constituency tilts more and more towards one policy alternative or another and the legislator votes against the favourable policy alternative – the number of policy losers in the constituency grows. The more policy losers there are, the greater is the electoral risk for office‐seeking legislators, as constituents can impose sanctions on incongruent legislators. Therefore, legislators are incentivized to engage in rhetorical responsiveness the larger the discrepancy between the aggregate policy position of the constituency and their own vote.

This argumentation is applicable to both the perspective taking and exchange rhetorical strategies. Legislators can offer their disgruntled constituencies rhetorical compensation either in the form of benefits, material or symbolic, or in the form of taking on their perspective and manifesting it in parliamentary debate. This likelihood increases with the widening of the gap between the legislator's policy actions and his/her constituency's aggregate policy preferences. Hence, we posit that

H2a. The likelihood for a legislator to use either the perspective taking or the exchange compensatory strategy grows as the representational deficit grows larger.

However, we expect the use of the (re)interpretative compensation to follow a different pattern. Specifically, we hypothesize that, with the build‐up of a conflict between the legislator and the constituency, the likelihood of (re)interpretative compensation will decrease. In constituencies which demonstrate a clear aggregate preference towards a given policy alternative over another legislators will resort to (re)interpretative compensation less frequently than in constituencies with a more uncertain aggregative preference. This assumption is based on the nature of the (re)interpretative compensatory strategy, which is essentially a reframing of the principals’ policy position to align with that of the legislator. As we mentioned above, since the use of discursive compensational strategies is meant to assist legislators in avoiding blame and sanctions, they are expected to craft their use of compensational strategies based on the benefits each strategy provides them, given the representational deficit context. The strategy of reinterpretation is not expected to be very useful when the constituency is overwhelmingly in favour or against a specific policy, since it is very hard to differently reframe such a position and present it as congruent with a contradictory policy option. Therefore, we expect this strategy to be mostly in use in constituencies with uncertain or mixed aggregate preferences.

We relate to Philippe Converse's (Reference Converse and Tufte1970) work on attitudes and non‐attitudes as well as to the well‐established literature which argues that citizens' policy preferences are not exogenous to the policy process and that voters' preferences and views are shaped at least in part by elite political communication (see, e.g., Barber & Pope, Reference Barber and Pope2019; Bolsen et al., Reference Bolsen, Druckman and Cook2014; Broockman & Butler, Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Lenz, Reference Lenz2009; Reference Lenz2012; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2010; Slothuus & Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021). When the constituency does not have a clear and crystalized aggregate preference, the legislator is more likely to use a rhetorical strategy which presents her policy actions as congruent with the constituency's preference, in an attempt to affect the actual preferences of individual constituents, or at least their satisfaction with the policy enacted. Clearly, such an approach is more difficult to implement when there is a clear and decisive majority in the constituency in favour of one policy preference or another because such preferences are less prone to reinterpretation. Therefore, we expect the use of this strategy to be maximal when the constituency's aggregate preferences are mixed or divided and therefore inconclusive.

H2b. The likelihood for a legislator to use the (re)interpretative compensatory strategy diminishes as the representational deficit grows larger.

Case selection: The British referendum and plenary discussions on the Brexit deal

We test our hypotheses using the case of the 2016 referendum in the United Kingdom and the parliamentary debates on the Brexit deal in the House of Commons. We chose this case for four reasons. First, under normal circumstances, the preferences of voters are difficult for legislators to gauge with any degree of accuracy (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Jansen, Sevenans, Soontjens, Pilet, Brack, Varone, Helfer, Vliegenthart, van der Meer, Breunig, Bailer, Sheffer and Loewen2023). In the Brexit referendum, however, legislators were informed about their respective constituencies’ preferences before they took action in parliament (see Hanretty, Reference Hanretty2017). In this case, we could also investigate how legislators compensated incongruent constituencies. In each voting scenario examined, we were able to determine the legislator's vote and the aggregate preference of her constituency and examine the legislator's parliamentary speech on the issue. Based on this information, we were able to identify legislators who were in representational deficits vis‐à‐vis their constituencies.

Second, in each of the two largest UK parties, Conservatives and Labour, the legislators were divided in their votes. Such a within‐party division is a necessary condition for identifying conflicting pressures. Otherwise, the influence of the legislator's party affiliation on her vote and use of compensatory strategies would be conflated with that of her constituency (or other principals), and these variables cannot be disentangled. Furthermore, estimates suggest that around half of the legislators in Parliament were out of step with their constituents as regards Brexit (Hanretty, Reference Hanretty2017). Again, this variability allowed us to examine the representational deficits that ensued and the ways in which the legislators coped with them.

Third, Brexit was a high‐salience policy issue that had great relevance and importance to all of the actors in the system. Most policy issues affect some segments or groups more than others, thus engaging some actors, while leaving others rather indifferent. In striking contrast, the Brexit question affected everyone. We can assume that all of the political actors were engaged to a similar extent.

Fourth, in the House of Commons the decision to speak in the plenary rests with the members themselves; party leaders have little control over which legislators speak in the debates (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012). Therefore, we can assume with a fair degree of confidence that, in the debates analysed, all legislators who wanted to speak were given the opportunity to do so.

Despite its clear advantages, we acknowledge that the case of Brexit is quite exceptional in its scope of influence and consequences. It is also equally distinctive in terms of the features that are salient for this study. Based on the results of the referendum, the principals' preferences were visible, verifiable and institutionally sanctioned. As already mentioned, in other political scenarios, legislators are not necessarily aware of the public's preferences and must make decisions based on partial information regarding the stances and attitudes of the principals they represent. To mitigate this uncertainty, legislators often use public opinion polls and other measures. Crucially, however, even in the case of Brexit – in which the preferences of the principals were supposedly clear – an element of uncertainty remained, due to the variation in the strength of the constituents’ aggregate preferences. Accordingly, our hypotheses tap into the extent to which a legislator's compensatory rhetoric is contingent on the size of the representational deficit she faces, evaluated by the strength of the constituents’ aggregate preferences. In what follows, we discuss the empirical method of our investigation.

Empirical strategy

In this study, we explore legislators' communications with their voters via floor speeches in parliament. As per Friedrich (Reference Friedrich1968, p. 324), parliaments ‘not only represent the “will” of the people, they also deliberate’. Thus, speech in parliament – not only votes – is a tool through which legislators communicate their actions to the public. While it is true that legislative speech is not necessarily as public facing as other arenas, such as traditional or social media outlets, it still constitutes an important arena through which legislators communicate with the general public. Indeed, there is bourgeoning literature that conceptualizes legislative debates as forums where legislators strategically communicate their positions to others within and outside the legislature (Grose et al., Reference Grose, Malhotra and Van Houweling2015; Lin & Osnabrügge, Reference Lin and Osnabrügge2018; Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2012, Reference Proksch and Slapin2015; Slapin & Proksch, Reference Slapin and Proksch2010; Reference Slapin, Proksch, Saalfeld and Strøm2014; Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2020). Thus, legislators construct their speeches in parliament with the objective of having key extracts from them circulated to the broader public by their parties and journalists (Proksch & Slapin, Reference Proksch and Slapin2015), as well as through their own social media accounts.

In addition, studies have shown that legislators who cannot provide their principals with their preferred policy outcomes often resort to parliamentary speeches. For example, Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2008) demonstrate that legislators from coalition parties use parliamentary debates to justify their policy compromises in government to their voters, while still voting with the government. In Ireland, legislators from coalition parties who represent constituencies that are economically vulnerable have been more vocal in parliament in their opposition to various cutback measures, despite voting with the government (Herzog & Benoit, Reference Herzog and Benoit2015). Proksch and Slapin (Reference Proksch and Slapin2012) establish that, in the United Kingdom, MPs at odds with their party leadership speak more frequently than their more amenable counterparts. Similarly, Proksch and Slapin (Reference Proksch and Slapin2010) show that, compared to their less recalcitrant colleagues, members of the European Parliament who are at odds with their European Parliament group and side with their national party make more speeches. All of these studies strongly indicate that legislative speech offers a window to ‘empirically investigate the arguments that representatives use to justify the pursuit of certain aims’ (Wolkenstein & Wratil, Reference Wolkenstein and Wratil2020). More specifically, by juxtaposing roll‐call votes and the floor speeches preceding them, we are able to investigate legislators’ strategies to cope with the pressures that arise from representational deficits.

We examined legislators’ rhetorical responsiveness in light of their respective vote choices. We used data from nine debates in the British Parliament held in conjunction with major votes on Brexit between January 2018 and October 2019. We retrieved the data on the legislators’ vote choices from the House of Commons website. Table A1 in the online Appendix describes the debates.

In order to determine whether a representational deficit arose vis‐à‐vis the constituency, we juxtaposed each legislator's vote choice in each of the nine votes with the aggregate preferences of her constituency on the Remain/Leave issue. We coded the legislators’ vote choice as congruent with the referendum's outcome (Leave) if they voted with the Conservative Party's position on the nine votes analysed, and as incongruent with the referendum (Remain) if they voted otherwise. We analysed each vote separately.

We realize that a Remain/Leave vote in the referendum is not strictly equivalent to the votes legislators take in parliament on specific votes relating to the Brexit deal. While the two are not equal, the votes legislators take in parliament on substantial Brexit discussions (such as May's or Johnson's exit deals) are in fact the way the political system translates and embeds the referendum's results into policy enactment. Since by and large the government‐opposition divide in British politics included the Conservative Party as promoting a leave policy and the Labour Party as promoting a remain policy, we consider a parliamentary vote as congruent with a leave constituency if the legislator voted with the Conservative Party majority. Clearly, this operationalization has its limitations, but it provides us with a clear measure to define congruence or lack of it.

For example, let us consider the 15‐Jan‐2019 division on May's withdrawal agreement. The majority of Conservatives voted for the bill, meaning that, for the purposes of this study, a vote in favour of May's deal was congruent with the Leave position. However, those who are known as the ‘hardline Brexiteers’ voted against the bill, as they saw it as too soft. Their votes will be categorized as incongruent with their constituency's Leave position. Even if these legislators believe they are acting according to the (Leave) policy preferences of their constituency, their voting behaviour still warrants explanation. Especially to constituents who voted Leave and are not aligned with the hardline Brexiteers position.

Next, we examined the legislators’ speeches, specifically, changes in their rhetoric when dealing with a representational deficit. Using the ParlSpeech V2 data set (Rauh & Schwalbach, Reference Rauh and Schwalbach2020), we extracted all speeches made by the legislators in the nine pre‐vote debates (see Table A2 in the online Appendix). Mentions of the constituency were identified in a two‐step process involving inductive expansion and validation. First, we created a custom dictionary comprising keywords capturing mentions of the constituency. Synonymous signifiers and edge cases were identified inductively from a sample of the corpus data and added to the dictionary, thereby expanding it. We used four keywords to identify the constituency: ‘local’, ‘community’, ‘area’ and ‘constituency’. We utilized case‐insensitive matching of the dictionary terms to find mentions of the candidates. In the second step, we manually verified the speech tokens that matched the dictionary to ensure that they indeed referred to the constituency, and any erroneous matches were discarded.

As a preliminary analysis, we examined the entire corpus of speech data at our disposal and compared the tendency to mention the constituency in the speeches of legislators facing a deficit to those of legislators whose vote was congruent with their constituency. We then calculated the raw proportion of discursive attention paid to the constituency among the deficit and non‐deficit groups as well as the estimated difference between the groups and its statistical significance.

In our core analysis, we assessed the legislators’ tendency to compensate the constituency rhetorically as a function of the size of the representational deficit. The population for this analysis was the legislators who were in a representational deficit vis‐a‐vis their constituency, and who mentioned the constituency in their speech. We then manually coded the mention of the constituency based on our scheme for compensatory rhetorical strategies: perspective taking, exchange and (re)interpretative. We investigated which if any of these types of rhetorical compensation the legislators used. The three rhetorical strategies were coded independently as binary variables because they are not mutually exclusive. The coded unit consisted of a validated mention of the constituency in a sentence and two other sentences: one preceding and one following it, providing context. Addendum A to the online Appendix describes the coding scheme in greater detail.

The main independent variable in our analysis is the size of the representational deficit the legislator faces. We operationalized this variable using the strength of the constituency's aggregate position on the Brexit vote, calculating the absolute difference between the score for ‘undecided’, which is 50, and the actual vote share for Leave in the constituency. Thus, a constituency in which 60 per cent voted Leave, and one in which this ratio was 40 per cent, would both receive a score of 10 (|60–50|; |40–50|). In contrast, if 70 per cent voted to Leave, the score would be 20 (|70–50|).

We controlled for the legislator's gender, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, seat security (measured as the difference in vote share amassed in the previous elections by that legislator and the second most successful candidate in the constituency) and tenure. We also controlled for MPs' political ambition using the Frontbencher/Backbencher status of MPs as well as for MPs' own ideological orientation regarding Brexit (Trumm et al., Reference Trumm, Milazzo and Townsley2020). The latter variable is based on MPs' declared EU referendum vote in 2016Footnote 6 and contains four categories: Leave, Remain, not declared and new MP, for MPs in our data set who were not in office during the referendum and their declared Brexit preference is, therefore, unaccounted for. Finally, we controlled for the share of votes in the legislator's constituency for UKIP in the 2017 elections and the share of people in the constituency born in the UK according to the 2011 census. We collected or processed the information for these control variables from the Comparative Legislators’ Database (Göbel & Munzert, Reference Göbel and Munzert2021) and the British General Election Constituency Results Dataset (Norris, Reference Norris2019). Addendum B to the online Appendix explains the units of analysis and the creation of the independent variable in more detail. In all of the analyses, we used clustering at the level of individual legislators. Utilizing a logistic regression model, we examined the effect of the size of the representational deficit on a legislator's tendency to employ each of the three types of compensatory strategies.

Results

Legislators' use of discursive attention when policy congruence is absent

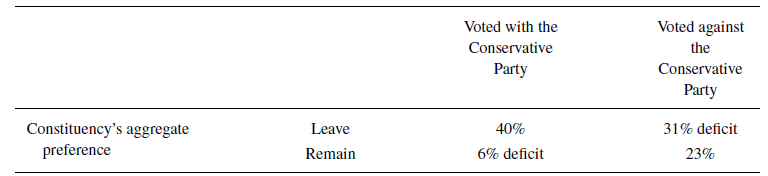

We begin our empirical analysis with a short descriptive observation about the extent of the representational deficits vis‐à‐vis the constituency. Table 1 presents the empirical description of the sources and the frequency of representational deficits vis‐à‐vis the constituency. The table lists the share of legislators facing a representational deficit in relation to the constituency, based on the discrepancy between the legislator's vote and the aggregate preferences of the constituency. We use this analysis to illustrate our basic assumption. In making a voting decision, a legislator must make choices with regard to policy, which often creates a representational deficit. Indeed, our data show that representational deficits are quite common: 37 per cent of legislators in our data set were in a representational deficit in relation to their constituency. A large proportion of these legislators – 31 per cent – represented constituencies who favoured leaving the EU. In contrast, only a small percentage – 6 per cent – represented those who wanted to remain in it. These results raise interesting questions regarding how legislators address such deficits and their use of compensatory speech acts in order to re‐establish their rhetorical responsiveness.

Table 1. Representational deficits vis‐a‐vis the constituency

Note. Share of legislators facing a representational deficit vis‐à‐vis their constituency based on a comparison between the legislators’ votes and their constituencies’ aggregate positions on Brexit.

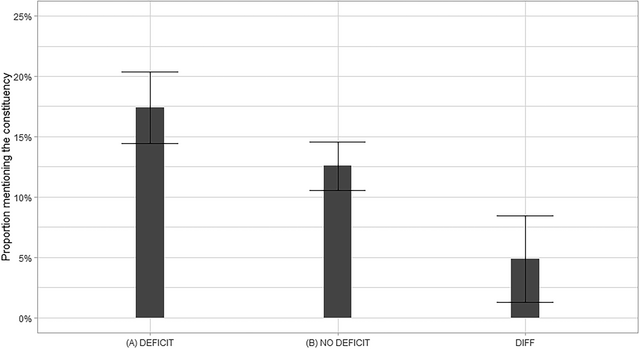

First, we asked whether these 37 per cent of legislators who were at odds with their constituency in terms of policy adaptation directed more discursive attention to their constituencies, compared with those who were congruent with their constituencies. Figure 1 provides the answer to this question. Legislators who found themselves at odds with their constituency mentioned it more often in their floor speeches than legislators whose policy actions were congruent with their constituency's aggregate preferences. As the ‘DIFF’ column indicates, this difference was statistically significant (as the confidence intervals differ from zero). The results of this preliminary analysis, which are consistent with previous studies (e.g., Umit & Auel, Reference Umit and Auel2020), confirm H1. They suggest that legislators are indeed more discursively attentive to principals whose preferences they did not support in their votes. This result makes sense as discursive attention can be thought of as a basic condition for rhetorical compensation.

Figure 1. Legislators' discursive attention to congruent and incongruent constituencies. The raw proportion of constituency mentions by legislators is based on the existence or lack thereof of a representational deficit. The DIFF column represents the estimated difference between the two groups. 95 per cent confidence intervals are added. (See Table A3 in the online Appendix for additional information.)

Before we move on to our next analysis, we address the effect of gender and ethnicity on legislators' legislative speech. While in this study we consider both as control variables only, legislative debates can play a crucial role in the representation of women and minorities. Past literature has focused on women MPs' floor access and frequency of legislative speech (Bäck et al., Reference Bäck, Debus and Müller2014, Reference Bäck, Debus, Fernandes, Bäck, Debus and Fernandes2021; Osborn & Mendez, Reference Osborn and Mendez2010; Pearson & Dancey, Reference Pearson and Dancey2011), on the dynamic surrounding women MPs' speeches in parliaments (Och, Reference Och2020; Vallejo Vera & Gómez Vidal, Reference Vallejo Vera and Gómez Vidal2020) and on the representative content of women MPs' speeches (Wäckerle & Castanho Silva, Reference Wäckerle and Castanho Silva2023; Childs, Reference Childs2004; Swers, Reference Swers2002). Systematic research on how ethnic minorities utilize legislative debates to amplify their voices is still scarce (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Debus and Bäck2021). By and large, we do find some effect of gender and ethnicity on legislators' discursive patterns; however, this effect is somewhat inconsistent. Both women and non‐White MPs are more likely to mention their constituency in their floor speeches, compared to men and White MPs, respectively, when they are in a representational deficit vis‐à‐vis the constituency (see Table A4 in the online Appendix). For women, this pattern also holds when they are not in a representation deficit with their constituency. Moreover, both women and Black MPs are more likely to offer exchange compensation to their incongruent constituencies, compared to men and non‐Black MPs, respectively; however, similar patterns were not accounted for the two other rhetorical compensatory strategies (see Table A5 in the online Appendix). These findings are still preliminary; however, they can serve as suggestive evidence for the effect of gender and ethnic background on MPs’ legislative speech. Nonetheless, future research focused on this question is needed. More than anything, these findings can be regarded as tailwind to the broad literature sustaining the effect of MPs' personal characteristics on legislative behaviour and decision‐making.

The contingency of rhetorical responsiveness on the size of the representational deficit

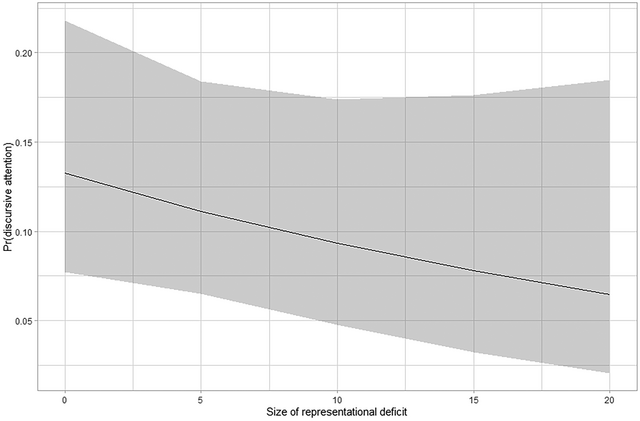

Our preliminary analysis confirmed that legislators use discursive attention in the absence of policy congruence. Next, we continue to examine the substantive qualities of such attention, which we claim are composed of compensatory speech acts. However, before doing so, we conducted one additional analysis of discursive attention that tied together the previous analysis and the following one. In this analysis, we investigated the role of the size of the representational deficit legislators face in the amount of attention they pay to incongruent constituencies (Figure 2).Footnote 7 Guided by the same logic of using discursive attention to re‐establish their responsiveness, it is reasonable to expect that the larger the representational deficit the more discursive attention legislators will pay to incongruent principals.

Figure 2. Legislators' discursive attention as a function of the size of the representational deficit. Predicted probabilities of legislators to mention the constituency in floor speeches based on the size of the representational deficit. The analysis draws on model 2 in Table A4 in the online Appendix.

Surprisingly though, this expectation does not hold. The size of the representational deficit has no significant effect on legislators' predicted probability of mentioning incongruent principals in floor speeches (see models 1 and 2 in Table A4 in the online Appendix). Figure 2, which is based on model 2 in Table A4, thus shows no effect of the size of the representational deficit on legislators' predicted probability of mentioning incongruent principals in floor speeches.

These inconsistent patterns pose an interesting question regarding legislators' use of explanations and the strategies they employ to convince their constituencies that they are responsive to their desires. Why is the relationship between the size of the representational deficit and legislators' likelihood of paying discursive attention to incongruent constituencies not positive? We argue that the reason lies in the different nature of the compensatory strategies legislators use to compensate incongruent constituencies, which all fall under the umbrella of ‘discursive attention’. As we previously argued and will show next, the discursive attention legislators pay to incongruent constituencies is comprised of three types of compensatory speech acts. The use legislators make of these rhetorical strategies differs depending on the types of compensatory speech acts. While the use of some becomes more likely as the representational deficit grows and constituents' aggregate preferences become more tilted towards a specific policy alternative and cohesive, the use of others becomes less likely. This can explain the non‐finding presented in Figure 2, as the opposite trends of compensatory speech acts cancel each other. Only a nuanced approach to the study of rhetorical responsiveness can flesh out and account for such differences.

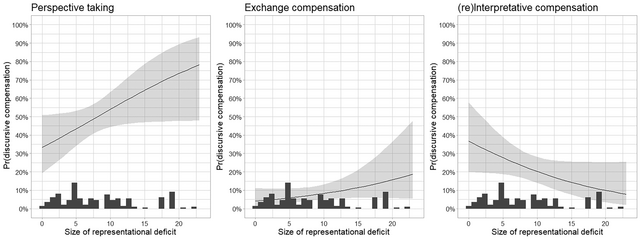

The models in Table A5 in the online Appendix demonstrate this explanation. They estimate the effect of the size of the representational deficit, measured as the strength of an incongruent constituency's aggregate preference (whether Leave or Remain) on the tendency of the legislator to target it with a rhetorical compensatory strategy. To account for the nested nature of the data which consists of mentions of the constituency nested in incongruent MPs, we utilize a logistic regression model and cluster the standard errors by MP. Figure 3 shows the predicted probabilities for compensation as a function of the size of the representational deficit. The range of the values on the horizontal axis corresponds to the empirical values of the strength of the constituencies’ preferences.

Figure 3. Estimated compensation across levels of representational deficit. Predicted probabilities for a constituency to be targeted with perspective taking, exchange and (re)interpretative compensation by legislators in a representational deficit, by various sizes of the representational deficit in the Brexit referendum. The analysis draws on models 2, 4 and 6 in Table A5 in the online Appendix. Values on the horizontal axis range between 0 and 20 in accordance with the real values of the strength of the constituency's preference. All other variables are kept at their respective means. Grey areas represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. The histogram depicts the distribution of the strength of the preference in the constituencies analysed. We considered 59 unique constituencies, but multiple observations might belong to the same constituency.

In line with H2a and H2b, Figure 3 shows a strong differential effect of the size of the representational deficit on the type of compensatory strategy deployed. When the constituency has a distinctive preference towards one policy alternative or another and the legislator is in a large representational deficit vis‐a‐vis it, the latter is more likely to use the forms of exchange or perspective taking to compensate the constituency.Footnote 8 On the other hand, in such scenarios, the probability of the legislator using (re)interpretative compensation sharply declines. These findings confirm H2a and H2b. They indicate that each type of compensation is subject to a different logic. (Re)interpretative compensation is deployed when the constituency's preference is indeterminate and lends itself to reframing. In contrast, exchange and perspective taking are considered appropriate when the constituency's preference is less vague. It appears, therefore, that legislators deal with different magnitudes of representational deficit by means of different rhetorical strategies of compensation.

For robustness purposes, we re‐ran this analysis excluding hardline Brexiteers. We did so since, as explained earlier, in the context of the Brexit referendum this group could be regarded as an outlier – Eurosceptic Conservative legislators who opposed the Conservative Party's position in parliament (a Leave position) despite representing a Leave constituency. The analysis excluding the group of hardline Brexiteers, as well as a separate analysis including hardline Brexiteers only, can be found in Tables A6 and A7 as well as in Figure A1 in the online Appendix. Not only do the results of this robustness check hold, they are even stronger. This is especially true for the models presented in Table A6 in the online Appendix (which excludes hardline Brexiteers) in which the size of the representational deficit has a statistically significant effect on legislators' likelihood to engage in all three types of compensatory strategies. These findings lend further support to the argument we put forward.

The analysis presented in Figure 3 is important for two reasons. First, it allows us to rule out the effect of embedded or omitted personal characteristics of the legislator, which may make some more prone than others to utilize rhetorical responsiveness, regardless of the situation. Thus, it is not the legislators’ personal characteristics that predict their tendency to compensate their constituency rhetorically. It is their response to the size of the deficit that dictates this choice. Second, this exercise brings together old and new conceptions of responsiveness. It combines traditional conceptions of responsiveness, focusing on policy congruence, with new conceptions of the term exploring other means by which legislators can be responsive. Our findings show that the larger the magnitude of the traditional responsiveness gap is, the likelier legislators are to resort to communicative responsiveness measures.

Discussion and conclusion

This study joins a bourgeoning literature framing responsiveness as a communicative process that allows legislators to harness voter support even when they vote against the policy their constituents favour. As a result, we expand our investigation beyond roll‐call votes and examine legislators’ parliamentary speeches, which – unlike vote records – reflect what issues they care about and what their political priorities are. Furthermore, unlike vote records, the legislators’ texts lend themselves to nuanced analysis. Which principals do the legislators mention most often? How do they present the policies they support and those they oppose? Thus, the analysis of texts in conjunction with voting patterns provides a more fine‐tuned, reliable measure of legislators’ responsiveness when faced with representational deficits.

Before we discuss our findings, there are two scope conditions important to address that also motivate future research. Firstly, our use of parliamentary speeches assumes that legislators attribute value to this arena and hold the belief that their constituents pay heed to the explanations and justifications they provide. Whether constituents actually listen to legislators' floor speeches is an empirical question outside the scope of this paper, but a more important question is whether legislators believe constituents listen to their floor speeches. We argue that they do, building on vast recent literature which has shown that legislators use legislative debates to strategically communicate their positions. Nevertheless, it is crucial to comprehend not just how the media portrays representatives' legislative speeches, and how citizens perceive them but also the increasing significance of social media in this context (Fernandes et al., Reference Fernandes, Debus and Bäck2021). Politicians can use platforms like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to strengthen their rhetorical responsiveness: they can signal their specific preferences; explain why they voted not in line with the majority in their constituency or compensate policy losers they care about. Given the more permissive and adaptable nature of social media compared to legislative speeches, it is plausible to speculate that they provide fertile ground for enhancing rhetorical responsiveness. With social media assuming a pivotal role as a channel for representatives to showcase and deliberate their endeavours (Mueller and Saeltzer, Reference Mueller and Saeltzer2022; Saeltzer, Reference Saeltzer2022), forthcoming research should focus on scrutinizing legislative rhetorical responsiveness as manifested across diverse social media platforms.

A second scope condition addresses the question of saliency from two angles. The first is that of issue saliency. The case in point – Brexit – is clearly a high‐salience policy issue. As we mentioned earlier, we believe it makes a good case for an exploratory examination of a question not yet dealt with. The saliency of the issue creates a high engagement of legislators, and thus it might be argued that legislators are more likely to speak in parliament and to compensate incongruent constituencies on high‐salience issues, whereas on lower salience issues, legislators might be less likely to speak altogether. Moreover, the saliency of the issue may result in voters attributing higher saliency to their preferences on Brexit, making them care more about it. This brings us to the second way saliency should be incorporated in future studies – in examining – in addition to voters' aggregated preferences on a policy issue – the importance voters attribute to such policy. In this study, we capture the size of representational deficits according to the aggregate preferences of the constituency. However, as we mentioned earlier, more voters supporting (or rejecting) a given policy does not necessarily mean it is more or less important to the individual voter. To capture this, one must combine the voter's preference with the saliency she attributes to such a preference. Such examination is challenging as available data usually do not include information about the saliency voters' attribute to their preferences on policy issues. Moreover, it could be that voters for which a policy issue is extremely salient are able to exert substantial influence on legislators even if they are small in numbers, resulting in large representational deficits. While accommodating these complexities surpasses the scope of this study, future research should embrace the saliency question and formulate theories about its impact on legislators' rhetorical responsiveness to voters.

To recap, our analysis shows that legislators tailor their speeches in the plenary to incongruent constituencies, compensating the latter for having acted in contravention of their will. By focusing on the relationship between the use of rhetorical compensatory strategies as a function of the magnitude of the representational deficit, we show that the more determined incongruent principals are in their aggregate policy preferences, the more likely legislators are to use perspective taking and exchange compensation to convince these principals that they are still responsive to the latter's needs and desires. In such a situation, they are less likely to use (re)interpretative compensation to achieve this goal. Not only do legislators tailor their rhetoric to incongruent principals, but they also modify it according to the gap between the policy actions they took and the aggregate preferences of their principals. When the principals are indecisive and their preferences are unclear, legislators find it appropriate to use (re)interpretative compensation, reinterpreting the principal's position such that it aligns with their own. However, when the principals’ preferences are clear‐cut, legislators realize that reinterpretation is not an option. Therefore, they will try to compensate the principals by using perspective taking, manifesting the constituents’ point of view regarding the policy question, or offering them something in exchange for the legislators’ incongruent vote. The magnitude of the conflict in classic responsiveness terms – focusing on the legislators’ policy actions – is thus a strong predictor of the use of rhetorical responsiveness.

The relationship between the three different compensation strategies and the rhetorical decisions the legislators make about which one to choose is telling. Whenever there is a small representational gap, reinterpreting preferences (logos) is the legislators' most preferred rhetorical strategy. However, as the legislators' policy choices diverge further away from their constituents' preferences, perspective‐taking (pathos) and exchange (ethos) take place. In other words, the larger the representational gap between the legislators and their constituents, the more the legislators' rhetoric shifts from logos‐based compensation strategies to more personal and audience‐related ones. This choice is understandable. When the representational deficit is small, which often happens when the constituents' preferences are mixed and divided, it makes sense to use logos and try to reinterpret the constituents' position and reframe it as closer to that of the legislators. However, when the representational deficit is large and substantial, meaning that the constituency the legislator represents has a clear preference towards one policy alternative or another, legislators understand that such a reinterpretation is no longer possible. Therefore, they resort to ‘damage control’ rhetorical strategies such as exchange or perspective taking.

The findings contribute to our understanding of responsiveness and how legislators use speech acts in order to re‐establish it rhetorically. These questions have hitherto not been resolved in research, and the Brexit case provides a rich ground for such an explorative endeavour. We trust that this study has opened new avenues for addressing other issues related to representation. In particular, future research can examine whether legislators’ use of compensatory rhetorical strategies follows the patterns found here when it comes to other issues on the parliamentary agenda and in other national contexts. Moreover, while this study has focused on rhetorical responsiveness towards incongruent majority positions, future studies could shed light on how legislators make use of rhetorical resources to respond to incongruent minority positions (e.g., the minority in the constituency when the legislator's policy is in line with the majority) and how these differ from responses to majority positions.

Acknowledgements

For helpful and insightful comments, we thank Fabio Wolkenstein, Christopher Wlezien, the participants of the Political Representation Discourse in Light of the Crisis of Democracy Conference 2022 and the participants of the European Political Science Association Annual Meeting 2021. We thank the EJPR editors and reviewers for their valuable feedback. We thank Noam Peterburg and Mateo Cohen for their wonderful research assistance. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge the financial assistance of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, Grant #20.17.0.047PO allotted to Odelia Oshri and Shaul Shenhav. This study was funded by the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, Grant #20.17.0.047PO allotted to Odelia Oshri and Shaul Shenhav.

Funding Information

Fritz Thyssen Foundation, Grant #20.17.0.047PO allotted to Odelia Oshri and Shaul Shenhav.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Online Appendix

Additional supporting information may be found in the Online Appendix section at the end of the article:

Table A1: Debates Included in the Analysis

Table A2: Descriptive Statistics of the Corpus of Texts

Table A3: Two Sample Tests for the Equality of Proportions– Discursive Attention Paid to the Constituency by Deficit

Table A4: Regression Table ‐ Discursive Attention Paid to the Constituency by Strength of the Representational Deficit

Table A5: Regression Table – Compensatory Strategy Used towards the Constituency by Strength of the Representational Deficit

Table A6: Robustness analysis – Compensatory Strategy Used towards the Constituency by Strength of the Representational Deficit, excluding hardline Brexiteers

Table A7: Robustness analysis – Compensatory Strategy Used towards the Constituency by Strength of the Representational Deficit, hardline Brexiteers only

Figure A1: Robustness – subsample analysis (full sample, excluding hardline Brexiteers, hardline Brexiteers only)

Addendum A: Discursive Compensation Coding Scheme

Addendum B: Construction of the Unit of Analysis and Primary Independent Variable

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information