Introduction

As highlighted by Appleby in 1975(Reference Appleby1) ‘first dearth and then plague’ was a common saying in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, drawing on the relationship between harvest failures and outbreak of plagues, recognising the now well-described phenomenon of chronic undernutrition impairing many aspects of the immune response and making individuals susceptible to infectious diseases, especially in the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts(Reference Govers, Calder and Savelkoul2). Moreover, the transition from hunter-gatherers to agrarian societies with the aggregation of humans into sedentary agricultural settlements favoured infectious disease spread(Reference Dobson and Carper3). This expansion to cities, trade and the influence of an increased population on ecosystems has increased the emergence of infectious diseases and risks for epidemics and pandemics(Reference Piret and Boivin4). Throughout the historical interaction of humans and life-threatening pathogens a fundamental role of food and nutrition was appreciated, with it being recognised that optimal nutritional status was important for protecting against communicable diseases, despite the biological mechanisms of infectious diseases not being fully understood(Reference Birgisdottir5).

In commenting on the recent pandemic driven by COVID-19, attention has been drawn to nutritional status in modulating susceptibility to, and severity of, COVID-19, with malnutrition predisposing to infection in disadvantaged populations and the elderly(Reference Rodriguez-Leyva and Pierce6). To enhance our understanding of the role of nutrition and the spread of COVID-19, a series of manuscripts were recently published, as summarised in Mathers(Reference Mathers7), on nutritional aspects of this disease. The focus of those publications was the mechanisms of specific nutrients and/or nutritional status upon the severity of COVID-19. By way of summary these papers drew attention to the importance of avoiding nutritional deficiencies, including deficiencies of individual micro-nutrients, the importance of the gut microbiome and the nutritional maintenance of innate and adaptive immunity(Reference Mathers7).

We recently described how SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for COVID-19, through the power of tropism seeks out vulnerabilities to facilitate its propagation by self-assembly(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8). In turn, we also highlighted the vulnerability of SARS-CoV-2 as it attempts to traverse the upper respiratory tract mucosa; a mucosal layer protected by a unique mucosal immune system. Moreover, we(Reference Popovic, Martin and Head9) established a relationship between SARS-CoV- 2 diffusion in the mucosa and its affinity for the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) target, and in doing so, we speculated that the very earliest contact of this virus with the human mucosa defines the subsequent pathogenesis of this infection. It is important to note that early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Russell et al.(Reference Russell, Moldoveanu and Ogra10) proposed a significant role for mucosal immunity, and for secretory as well as circulating immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies. In this review we seek to explore further the vulnerability of SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract mucosa with emphasis on the intersection of mucosal immune function, nutrition and prevention of infection.

COVID-19, a diverse constellation of complex pathophysiological pathways: an argument for early prevention

The progression of COVID-19 within a human and across populations is nonlinear, multifactorial, occurs at many levels and to be fully understood requires systems analysis thinking(Reference Head and Buckley11). In the healthy state, understanding human variability, as it applies to human nutrition, also involves embracing the principles of complex science(Reference Head and Buckley11). Valdés et al.(Reference Valdes, Moreno and Rello12) noted that COVID-19 infection reflects a broad spectrum of patient symptoms driven by a diversity in pathophysiology in a myriad of physiological pathways altered during the time course of the disease. Variability in responses to nutritional intake, combined with variability in responses to COVID-19 infection adds complexity to determining the potential role for nutrition in the prevention and/or management of COVID-19.

Dysregulated, uncontrolled inflammation as the host response migrates from the upper airway to the lower respiratory tract is the hallmark of serious COVID-19(Reference Lumbers, Head and Smith13). It follows at this stage of the disease progression that agents, including nutrients with anti-inflammatory properties, may be beneficial. However, as we have summarised recently(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8), just prior to lower lung infection there appears to be a dampened nasal interferon and inflammasome response. The predicted robust type 1 and 3 interferon responses are moderated, thereby reducing the pro-inflammatory setting that normally affords host protection but now permits the virus to replicate and spread to bystander cells. Moreover, this inflammatory silence becomes more of a problem as it may result in asymptomatic infectivity, which can promote spread. In the landmark RECOVERY trial(Reference Group, Horby and Lim14) dexamethasone reduced mortality in COVID-19 cases in those receiving respiratory support (i.e., oxygen), while no benefit, and indeed the possibility of harm, was seen in patients who did not require respiratory support(Reference Group, Horby and Lim14). Vegivinti et al.(Reference Vegivinti, Evanson and Lyons15) reported that steroids were more effective when given early in the disease course, at a time when viral infection and replication was minimal and before the rise in complexity of the pathophysiology. Overall, the temporal dependency of treatment efficacy that is evident from these trials illustrates the difficulties and challenges in identifying effective treatment approaches during the many complex stages of progression of COVID-19.

Given we have proposed that the SARS-CoV-2 virus is at its most vulnerable early in infection as the virus diffuses across the upper airway mucosa to reach its target protein on the epithelium(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8), mucosal IgA antibodies, if available and functional, may play a key role in prevention of infection. Specifically, IgA protects the epithelial barriers from pathogens and an early SARS-CoV-2 specific response dominated by IgA antibodies contributing to virus neutralisation may reduce the risk of infection(Reference Quinti, Mortari and Salinas16).

COVID-19 is a consequence of a clash between a highly conserved human viral target receptor (ACE2) and a highly conserved human respiratory tract immune response to the viral pathogen. The SARS-CoV-2 receptor target, ACE2, appeared early in evolution, about 550 million years ago (summarised in Lumbers et al.(Reference Lumbers, Head and Smith13)). The human immune response to that viral attack also has ancient origins. For example, Yu et al.(Reference Yu, Huang and Kong17) have provided evidence that air organs and specialised mucosal immunoglobulins (Igs) are part of an ancient partnership that predates the emergence of tetrapods, and that the development of the lung is originally from the anterior foregut endoderm.

Lungs are exposed to pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2, and have evolved an inducible protective mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). The nasopharynx-associated lymphoid tissue (NALT, discussed in detail later) is key in our current defence against airborne pathogens and was thought to have emerged 200 million years ago(Reference Tacchi, Musharrafieh and Larragoite18). An essential component of the protective function of MALT is the secretion of immunoglobulin (Ig) A (IgA) as secretory IgA (sIgA). IgA is analogous to IgT in teleosts. IgTs are the most ancient Igs specialised in mucosal immunity against parasitic and bacterial pathogens(Reference Yu, Huang and Kong17). Of significance is the demonstration of IgT within the nasal mucosa and the suggestion that dedicated mucosal Ig performs an evolutionarily conserved role across vertebrate mucosal surfaces(Reference Yu, Kong and Yin19).

It is important in this context to contrast the evolution of two of our prominent antibodies IgA and IgG. IgG emerged as a ‘mammalian antibody’ with evolutionary divergence across mammalian species(Reference Butler, Wertz and Kacskovics20); whereas, NALT (now associated with IgA responses) emerged possibly 380 million years ago for pathogen protection of the olfactory epithelium in aquatic vertebrates and later adapted to defend against inhaled antigens in land-based vertebrates(Reference Tacchi, Musharrafieh and Larragoite18).

Collectively this evolution of a highly conserved, inducible mucosal-associated lymphoid protective barrier over millions of years produced the setting for our current upper airway pathogen protection. More recently it has been a combination of the landmark clinical findings from polio vaccination research, the clinical observations on the impact of enteral and parental feeding, as well as the powerful insights gained from studies of immunity with maternal neonate feeding that has contributed to our understanding of this primary protective mucosal lymphoid immune process.

Mucosa. Fundamental lessons from polio vaccination and mucosal immunity

The use of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) given by injection and oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) has illuminated the importance of the mucosal secretion of IgA in viral protection in humans. In doing so, this comparison emphasises the distinction between the mucosal immune system and systemic immunity.

As highlighted by Hird and Grassly(Reference Hird and Grassly21), immunisation with the oral live-attenuated polio vaccine (OPV) induces sIgA, and this is associated with reduced shedding of poliovirus from the intestine. It is thought that the OPV prevents infection by way of viral neutralisation with mucosal IgA(Reference Blutt and Conner22). By way of distinction, injection of the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), as summarised by Donlan and Petri(Reference Donlan and Petri23), fails to produce a mucosal immune response and under these conditions viral shedding from the intestine can continue after infection. Thus, while systemic immunity is widespread in humans and utilises IgG, mucosal immunity utilises IgA to protect the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems(Reference Donlan and Petri23). By way of explanation, Donlan and Petri(Reference Donlan and Petri23) described how OPV induced IgA antibodies against poliovirus in the duodenum by inducing antibody-producing B cells, facilitating CD4+ T cells and locally producing cytokines such that B cells in the mucosa (but not systemically) are activated. Of critical importance were the observations in children previously immunised with live polio vaccine and studied before and after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (Ogra(Reference Ogra24)). Before operations, poliovirus IgA antibodies, but not IgG or IgM antibodies, were present in the nasopharynx. After operations, the IgA antibodies in the nasopharynx declined markedly, with some children who previously displayed IgA antibodies failing to do so after operation. Moreover, children with intact tonsils had prevailing antibody responses in the nasopharynx that were much higher than those seen in children in whom the tonsils were removed. Collectively these studies highlighted the presence of a nasopharyngeal lymphoid response associated with the IgA antibody following vaccination with the oral live attenuated poliovirus vaccine. The tonsils are viewed as part of an immunological network acting on external mucosal surfaces(Reference Ogra, Faden and Welliver25). Subsequently it has been demonstrated that adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy were associated with a two- to threefold increase in upper respiratory tract diseases(Reference Byars, Stearns and Boomsma26). In addition, CD-10, a marker for B lymphocytes was lower in children undergoing tonsillectomy, suggesting a decrease in B cells and reduced antibody production(Reference Radman, Ferdousi and Khorramdelazad27). Collectively these observations following tonsillectomy highlight the importance of the tonsils in the pharynx and palate with their ability to immediately activate the immune system when in contact with pathogens(Reference Semih and Doblan28).

The application of IPV given by injection and oral OPV has revealed the presence of a unique networked mucosal immune system utilising IgA antibodies. This immune system provides the framework to explore the role of the gastrointestinal system and its link to respiratory tract immunity in the protection of the lung from pathogens including viruses.

Critical lessons from enteral feeding and respiratory immunity

In 1983 Kudsk et al.(Reference Kudsk, Stone and Carpenter29) demonstrated that in animals enteral feeding was important in survival after haemoglobin– Escherichia coli adjuvant peritonitis. Subsequently Moore et al.(Reference Moore, Moore and Jones30) conducted a prospective clinical trial in which they compared total enteral feeding (TEN) with total parental feeding (TPN) in critically injured patients. They demonstrated that early TEN feeding via the gut reduced septic complications. Establishing a mouse-specific influenza virus immunity, Kudsk et al.(Reference Kudsk, Li and Renegar31) showed a preservation of upper respiratory tract immunity with enteral feeding, whereas parenterally fed mice, despite being immunised against A/PR8 (HINI) influenza virus, exhibited impairment in IgA-mediated upper respiratory tract immunity.

Li et al.(Reference Li, Kudsk and Gocinski32) highlighted a correlation between gut-associated lymphatic tissue (GALT) atrophy and decreased levels of intestinal, intraluminal IgA. These authors highlighted GALT as an independent immune organ offering protection for distal mucosal sites including the nasopharynx, salivary glands and lung(Reference Li, Kudsk and Gocinski32). In developing a model of respiratory immunity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia, King et al.(Reference King, Kudsk and Li33) identified that protection against bacterial pneumonia was lost with TPN and completely preserved with chow or complex enteral diets. Within GALT, Th1 cytokines down regulate IgA production and Th2 cytokines upregulate IgA production. The IgA stimulating cytokine, IL-4, is increased and the IgA reduced in mice with TPN(Reference Wu, Kudsk and DeWitt34). Importantly the balance between IgA stimulation and inhibition is maintained with complex enteral diets(Reference Wu, Kudsk and DeWitt34).

In addition to the activity of IgA being aligned with the gut-associated lymphatic tissue and immune protection derived from the gut in anatomically distant sites, such as the lung, there have been recent findings describing a closely linked relationship between gastrointestinal microbiota and pulmonary immunity. As highlighted by Anand and Mande(Reference Anand and Mande35), there is growing support for the concept of a ‘common mucosal response’ involving the microbiota and mucosal immunity on distant mucosal sites, including the lung. T and B cells, induced in the Peyer’s patches, migrate within circulation to the intestinal regions as well as bronchial epithelium, with IgA produced from the B cells relaying the immunological knowledge between the gut and lung. Moreover, it would appear there is a duality of function of IgA in excluding pathogens as well as promoting colonisation of commensals(Reference Huus, Bauer and Brown36). The interactions involving the microbiota are well described by Sencio et al.(Reference Sencio, Machado and Trottein37).

McAleer and Kolls(Reference McAleer and Kolls38) showed the importance of the gut microbiota in determining the nature of lung inflammation, including the role of short chain fatty acids (SCFA) generated in the gut. It is noteworthy that the SCFA, acetate, a product of bacterial fermentation of resistant starch, may microbially induce CD4+ T cells to support T-cell-dependent IgA(Reference Takeuchi, Miyauchi and Kanaya39). The absence of enteral feeding may also be associated with changes in bacterial community with a decrease in the release of sIgA at the mucosa(Reference Pierre40).

The significance of the interactions of enteral feeding and respiratory immunity relates to an understanding of the basis of pulmonary protection to serious pathogens such as the influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. Collectively these findings provide evidence of a relationship between respiratory tract immunity, food/nutrition and the gastrointestinal system. Clarity regarding the details of this relationship comes from studies on maternal feeding in neonates and is explored below.

Lessons from maternal feeding in the human neonate

There is a view that humans are immature at birth with evolved altricial traits distinct from the precocial characteristics of higher mammals(Reference Bluestone41). While it can be argued that an advantage of being born in an immature state permits a uniqueness in brain growth and development in the first year of life, there is also an immaturity in the immune system with a susceptibility to infection in early infancy(Reference Bluestone41). It follows that this immaturity in acquired immunity leads to a reliance upon maternal antibodies for defence against pathogens(Reference Ballard and Morrow42). This dependency may well provide advantageous, as discussed by Macpherson et al.(Reference Macpherson, Yilmaz and Limenitakis43), as maternally derived antibodies may shield the offspring from premature stimulation from their own mucosal system with long-term effects on the acquired microbiome. As suggested by Molès et al.(Reference Moles, Tuaillon and Kankasa44), the neonatal gut can be viewed as a temporary extension of the placental role, and breast milk a continuum of the role of human blood in the provision of soluble factors and immunologically active milk cells. The constant transfer and allocation of maternal cells to the infant intestinal mucosa is facilitated by a process of micro-chimerism(Reference Moles, Tuaillon and Kankasa44,Reference Lokossou, Kouakanou and Schumacher45) . Maternal cells support the immunological maturation and immune defence of the newborn(Reference Lokossou, Kouakanou and Schumacher45). This microbial protection includes the interplay of the mucosa, the transfer of IgA immunity in partnership with sustenance and the establishment of the gastrointestinal microbiome.

The immaturity of the infant immune system at birth has provided the most remarkable opportunity in understanding the intricacies of mucosal immunity as a protective barrier of critical importance, and one from which to view mucosal protection from infection with SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19. Three observations provide insights to the intricacies of mucosal immunity.

Serum IgA deficiency in full term neonates

At birth, infants are serum IgA (sIgA) deficient and, as highlighted by Walker(Reference Walker46), take about 30 days to produce protective levels after activation of sIgA plasma cells by way of bacterial colonisation and fermentation of non-digestible oligosaccharides from breast milk. sIgA is the predominant antibody in human milk, with IgM and IgG antibodies becoming more abundant later in lactation(Reference Ballard and Morrow42). IgA is the most important immunoglobulin in milk, in concentration and biologic activity(Reference Lawrence, Lawrence and Lawrence47). Infant microbial and antigen protection is achieved by sIgA antibody transfer in the mother’s milk. Thus, the collective sIgA is due to the presence of a variety of mammary gland-associated specific sIgA antibodies that had been primed at an intestinal level(Reference Cruz, Cano, Cáceres, Mestecky, Blair and Ogra48). The spectrum of viruses for which antibodies in milk can be present is quite extensive. Lawrence(Reference Lawrence, Lawrence and Lawrence47) has highlighted some of the viruses for which sIgA antibodies may be present in milk and these include enteroviruses (poliovirus, coxsackie, and echovirus), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Semliki Forest virus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), rubella, reovirus type 3, rotavirus and measles. Specific sIgA antibodies for influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 present in milk are discussed later.

The role of lymphoid tissue

The transfer of IgA immunity from mother to infant is remarkable and described by Lawrence(Reference Lawrence, Lawrence and Lawrence47). As suggested, the mammary gland may be viewed as an extension of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and possibly the bronchiole-associated lymphoid tissue. sIgA secreted into the milk is produced by plasma cells in the basolateral region of the mammary glands(Reference Guo, Ren and Han49). As highlighted by Lokossou et al.(Reference Lokossou, Kouakanou and Schumacher45), in this entero-mammary pathway, chemokines mediate the migration of B cells to the mammary glands, subsequently permitting the accumulation of IgA-secretory cells in the mammary gland, explaining the predominance of the IgA class of immunoglobulins in breast milk.

IgA and the microbiota

There is little doubt that a key role of antibodies is in the neutralisation of pathogens. However, there is a role for antibodies in the functional aspects of microbial non-pathogens(Reference Macpherson, Yilmaz and Limenitakis43). Strains of gastrointestinal bacteria are shared between the mother and infant(Reference Lokossou, Kouakanou and Schumacher45), and the initial colonisation occurs by vertical transmission(Reference Dalby and Hall50). The binding of IgA to the microbes can either inhibit or enhance their colonisation, and promote their clearance by aggregation or enhance their presence by binding to commensals, such as Lactobacillus (Reference Guo, Ren and Han49). Moreover, the sIgA in milk formed from IgA/plasma cells in the mammary gland, that were originally in gut, have been trained by the maternal microbiota(Reference Guo, Ren and Han49). In this way the immune system manages the host–microbial symbiosis, but in turn, the microbiome trains and develops key components of the host innate and adaptive immune system(Reference Zheng, Liwinski and Elinav51).

Additional maternal modulation occurs with breast milk, which contains prebiotic oligosaccharides that are not digested before the colon and are fermented by the colonic flora to form short chain fatty acids (SCFA). Breast milk-fed infants have an increased probiotic proliferation of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacilli, and the probiotics stimulated by colonic fermentation enhance secretion of polymeric IgA that protects mucosal surfaces against harmful bacterial invasion(Reference Forchielli and Walker52). In turn, sIgA binding to select commensals, such as Lactobacillus, can increase their mucosal colonisation(Reference Guo, Ren and Han49). The stimulation of the production and secretion of polymeric IgA contributes to the development of longer-term intestinal defence in the offspring(Reference Forchielli and Walker52). Guo et al.(Reference Guo, Ren and Han49) note that in pregnancy and lactation, the gut and vaginal microbiota of mothers change to facilitate the expansion of commensals such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. The mode of delivery may have, possibly via gut microbiota development, significant effects on immunological functions in the infant(Reference Huurre, Kalliomaki and Rautava53–Reference Thompson55).

Maternal feeding in the human neonate illustrates the protective barrier role of the mucosa, lymphoid tissue and the intricacies of mucosal immunity, with the pivotal role of IgA antibodies. This interconnectedness of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues and the relationship with IgA underpins the development of immunity by way of antigen recognition and the microbiome. Features that are very prominent in mucosal barrier protection against SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19.

Lessons derived from gastrointestinal mucosal immune defence with its concurrent tolerance to food antigens and commensal bacteria – a networked common mucosal inductive and effector immune system

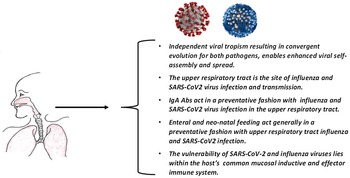

Drawing upon the findings of landmarked studies highlighted immediately above and summarised in Fig. 1, the view has emerged that key to viral defence in humans is common mucosal lymphoid tissue that affords pathogen protection across multiple organs and tissues, including the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. A protective process that has strong links to food and nutrition. An understanding of the cellular and molecular basis of the mucosal protective network is essential in designing approaches to exploit the vulnerability of SARS-CoV-2 in its obligatory passage across the nasopharyngeal mucosa in its attempt to infect humans.

Fig. 1. Approaches to understanding the mucosa, nutrition and immune system in COVID-19. A networked common mucosal inductive and effector immune system.

Understanding mucosally induced tolerance and immune defence has been studied for decades(Reference Brandtzaeg and Pabst56) and is dependent in part on the formation and migration of secretory antibodies as a key platform for the mucosal immune system. Steele et al.(Reference Steele, Mayer and Berin57) have shown the mucosal immune system is in a state of active tolerance with commensal bacteria and food antigens, and disruption of this tolerance occurs with food allergies, for example. To this extent, it has been observed that the mucosal immune system is more complex than the systemic immunity equivalent in regard to effectors and anatomy(Reference Brandtzaeg and Pabst56). The protection afforded by secretory IgA is twofold: by immune exclusion involving antigen complexes and by intracellular neutralisation to prevent viral replication(Reference Gozzi-Silva, Teixeira and Duarte58). The secretory IgA antibody protects the epithelium from pathogenic organisms by restricting their access to the epithelium and, at the same time, influencing the composition of the gastrointestinal microbiota(Reference Mantis, Rol and Corthesy59). In addition, by binding antigens in the gastrointestinal lumen, it prevents their uptake, and as such, this neutralising antibody is thought to play a protective role in food allergies(Reference Berin60), and therefore acts as an important contributor to gastrointestinal homeostasis. However, this homeostasis does not occur in isolation as it is interconnected by way of a sophisticated immune network.

The lung and the gut are strongly linked and influence each other’s homeostasis(Reference Anand and Mande35), and a fundamental basis of this linkage involves food, nutrition and immune function. Pierre(Reference Pierre40) summarises the decades of research into respiratory and gut immune tract changes associated with parental feeding and the accompanying risks of respiratory and abdominal infections. From those studies, attention has been drawn to the role of the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT) and adaptive and immune cell function. The formation and export of secretory IgA antibodies, and the ability to actively sample antigens from mucosal surfaces, are characteristics of the mucosal immune system(Reference Brandtzaeg and Pabst56).

It has been known for some time that the huge surface area of mucosal membranes is protected by IgA produced locally in subepithelial spaces of mucosal membranes and in secretory glands, and that antigen-sensitised IgA antibodies from GALT are disseminated to the gut and other mucosa-associated tissues(Reference Mestecky61). More recent focus has been on the role of GALT in antigen sampling and the release of sIgA to gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosal surfaces(Reference Pierre40). By way of summary and drawing upon excellent descriptions in this area(Reference Ogra, Faden and Welliver25,Reference Wu, Kudsk and DeWitt34,Reference Anand and Mande35,Reference Pierre40,Reference Brandtzaeg and Pabst56,Reference Mestecky61–Reference Tamura, Ainai and Suzuki63) the following pattern emerges regarding inductive and effector responses:

-

Mucosal lymphoid tissue is one of the largest immune entities in the body and reflects a large proportion of the body’s total immunoglobulin formation.

-

This mucosal immune system is composed of inductive and effector sites with the migration of cells from the from the inductive site through the lymphatic system to the effector site.

-

The mucosa inductive sites [mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)], for example, the Peyer’s patches in the small intestine, as well as the gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT), the nasopharyngeal-associated lymphoid tissues (NALT), larynx (LALT) and the bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). Also included in that immunologic network is the upper airway, tonsils and salivary glands.

-

Antigens bind to receptors on MALT and are internalised and then packaged and transferred to dendritic cells whereupon the carried antigens are carried to the inductive sites and initiate mucosal T- and B-cell responses. At the effector sites the cellular contribution to sIgA antibodies occurs. The effector sites are different from the inductive sites and can include the lamina propria of different mucosae and surface epithelia.

-

Subsequent release of sIgA protects the mucosal surfaces by way of specific and nonspecific binding with bound antigen, and subsequent phagocytosis leads to a dampened inflammatory immune-tolerant response.

-

These mucosal IgA forming cells move, for example, from the Peyer’s patches to the effector sites, including lymph and bronchial epithelium, via the circulation.

-

NALT and Peyer’s patches provide a two-tiered barrier for host–pathogen protection as inductive sites for mucosal IgA and serum IgG.

-

It is important to also note that commensals in the gut are also important for the induction and functioning of IgA, and its production is enhanced after colonisation with gut bacteria.

-

In this fashion, the gastrointestinal tract (inductive site) and the lung (effector site) are linked. This is key to understanding the link between nutrition, the microbiome, respiratory pathogens and morbidity.

It is this emergent knowledge of a common mucosal inductive and effector immune system that provides the foundation for understanding the gastrointestinal and lung axis in its preservation of upper respiratory tract immunity with enteral feeding in the pioneering studies of Kudsk et al.(Reference Kudsk, Li and Renegar31). Recently Pannaraj et al.(Reference Pannaraj, da Costa-Martins and Cerini64) have commented on the integrated mucosal immune system comprising the respiratory tract, the lactating mammary gland, the intestine and other mucosal sites, and that stimulation of one mucosal site may result in antibody production at another mucosal site.

With this knowledge it is now possible to understand the interaction of viral pathogens responsible for pandemics and endemics with the mucosal immune defence mechanisms. Accordingly, we have explored the characteristics of infections mediated by influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 with emphasis upon:

-

The upper respiratory tract as the site of initial viral infection.

-

The role of IgA antibodies.

-

The role of enteral feeding and viral infection.

-

The role of neonatal feeding and viral infection.

Why use nutrition to protect against infection?

On the basis of a detailed system and thermodynamic analysis(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8,Reference Popovic, Martin and Head9,Reference Popovic and Minceva65,Reference Popovic and Popovic66) , we were ultimately drawn to an understanding that the vulnerability of SARS-CoV-2 lies in its diffusion across human nasopharyngeal mucosal layers, a barrier that offers fundamental host protection by way of its highly conserved immunological processes. The importance of the immune barriers including not only the mucosal layers of the respiratory tract but also the gastrointestinal tract, has been recently highlighted(Reference Calder67). As food and/or nutrients can be absorbed across these tracts, it appears reasonable to consider effects of these foods and nutrients on the mucosal layers.

In the section above, we have drawn attention to the interaction between the gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory tract and the role of IgA. This interaction involves GALT as an independent immune organ, offering protection for distal mucosal sites including the nasopharynx, salivary glands, and lung through the release of IgA that circulates to these sites. Critically, with GALT atrophy, the levels of intestinal intraluminal IgA are decreased. Collectively findings define a relationship between respiratory tract immunity, food/nutrition and the gastrointestinal system. This is also a prominent discussion in in maternal feeding in neonates which is discussed in the section above.

Calder(Reference Calder67,Reference Calder68) specifically highlighted the importance of nutrition and immunity in the context of pathogen protection as it relates to COVID-19. This protection arises from the evolution of an array of cell types and molecules as part of the human immune system that protect the host from pathogens(Reference Vegivinti, Evanson and Lyons15). It follows that supporting or enhancing protective immune function with nutritional strategies is of importance when facing a highly infectious and dangerous pathogen such as SARS-CoV-2. Gozzi-Silva et al.(Reference Gozzi-Silva, Teixeira and Duarte58) showed that nutrients can ameliorate the development and severity of pulmonary diseases by acting on immune cells and modulating immune driven inflammatory responses. We hypothesised that the upper respiratory tract nasopharyngeal mucosal interface may represent a potential novel therapeutic and immunological target for preventing progression to serious COVID-19(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8).

Why focus on the mucosa?

The importance of the mucosa as a preventative barrier to pathogens including SARS-CoV-2 comes from two major considerations. Firstly, the vast knowledge base derived from the results of pre-clinical and clinical investigations that collectively provide evidence for a pivotal relationship between mucosal immunity, respiratory tract immunity, food/nutrition and the gastrointestinal system. We have summarised earlier many of the key studies describing mucosal immunity, which include studies on polio vaccines, enteral and parenteral feeding and the development of acquired immunity in the very young with maternal antibodies. The second area of support for the importance of the mucosa as a preventative barrier for SARS-CoV-2 comes from a thermodynamic understanding of viral diffusion in the mucosa and its subsequent target binding on the airway epithelium. Recently, we developed a mechanistic model of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infection, to define the relationship between the viral diffusion in the mucosa and viral affinity for its ACE2 target, which revealed that for SARS-CoV-2, the higher the affinity of ACE2 binding the more complete the mucosal diffusion from the upper airway to the region of the ACE2 target on the epithelium(Reference Popovic, Martin and Head9). Previously, attention has also been focused upon the lethality of SARS-CoV-2 being a consequence of the thermodynamic spontaneity of its binding to ACE2 as the prelude to human host cellular entry and replication(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8,Reference Popovic, Martin and Head9) . The viral transit across the mucosa is fundamental to the development COVID-19 for at least three reasons:

-

If SARS-CoV-2 is successful in diffusing across the nasopharyngeal mucosal barrier and binding to its ACE2 target, the subsequent upper airway infection will determine if COVID-19 is mild or asymptomatic (upper airway) or if it progresses to serious disease (lower respiratory tract).

-

SARS-CoV-2 displays a nasopharyngeal tropism that collectively involves the interplay between entropy and enthalpy, which results in a higher affinity for the ACE2 target than, for example, viruses such as SARS-CoV that do not exhibit this tropism to the same extent. This SARS-CoV-2 tropism is associated with an effective passage across the mucosal bilayer gradient, and most importantly, an enhanced efficiency of target-binding and subsequent epithelial cell entry mediated by a furin-sensitive polybasic cleavage site at the junction of S1 and S2 on the spike protein(Reference Head, Lumbers and Jarrott8).

-

The passage of SARS-CoV-2 across the nasopharyngeal mucosal barrier, while driven by nasopharyngeal tropism and favourable thermodynamics, is not assured, owing to mucosal immunity, which represents a fundamental area of extracellular vulnerability for this virus. This protective barrier of mucus, formed from mucins in goblet cells, is associated with antimicrobial peptides, cytokines and antibodies, with the latter being principally secretory IgA(Reference Gozzi-Silva, Teixeira and Duarte58).

Consistent with the protective properties of the nasopharyngeal mucosal barrier, there have been recent advances in enhancing mucosal immunity with vaccines. Nouailles et al.(Reference Nouailles, Adler and Pennitz69) showed that mucosal immunity at the site of virus entry is of paramount importance by demonstrating that intranasal immunisation provides protection against both the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 and the two variants of concern (VOC), B.1.1.7 and B.1.351. Consistent with this view, Afkhami et al.(Reference Afkhami, D’Agostino and Zhang70) indicated that intranasal, but not intramuscular, immunisation provided potent B- and T-cell dependent protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Subsequently, Jangra et al.(Reference Jangra, Landers and Laghlali71) drew attention to intranasal vaccination being more effective at inducing mucosal immune responses than systemic vaccination, providing improved protection, reduced viral transmission and improved mucosal immunity in the upper respiratory tract, which more effectively blocked viral dissemination into the lower respiratory tract.

In viewing the host factors associated with variations in influenza morbidity and mortality in the 1918 influenza pandemic Short et al.(Reference Short, Kedzierska and van de Sandt72) summarised six key factors, three of which are related to immunity (immunopathology, humoral immune response and cellular immune response) and one to malnutrition, illustrating the collective prominence of nutrition and immune responses in this highly infectious upper respiratory tract disease.

The upper respiratory tract is the site of influenza virus infection and transmission

By way of tropism, seasonal influenza viruses H1N1 and H3N2 bind to the α-2,6-linked sialic acid receptors of the upper respiratory tract and thereby facilitate transmission. The binding in the upper respiratory tract is in the region of the lymphoid tissue of Waldeyer’s ring – comprising the palatine tonsils, nasopharyngeal tonsil (adenoid), the lingual tonsil, the tubal tonsils and the lateral pharyngeal bands. It is the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) acting as the initial defensive barrier at the entry way to the respiratory and alimentary tract(Reference Hellings, Jorissen and Ceuppens73). As Tamura et al.(Reference Tamura, Ainai and Suzuki63) have highlighted, the respiratory tract mucosa is the site of infection and immune responses with the influenza virus. Several key observations illustrate this conclusion well:

-

With the use of genetically tagged and untagged influenza A/H1N1, A/H3N2 and A/H5N1 in experiments reflecting upper and lower respiratory tract infections, Richard et al.(Reference Richard, van den Brand and Bestebroer74) demonstrated that the influenza virus replication was in the nasal respiratory epithelium of the upper respiratory tract and is a driver for the transmission of influenza A viruses in the air.

-

In 2014 Lowen et al.(Reference Lowen, Bouvier, Steel, Compans and Oldstone75), in referring to previous studies(Reference Lowen, Steel and Mubareka76,Reference Seibert, Rahmat and Krause77) , highlighted that passive immunisation of guinea pigs with a neutralising mouse monoclonal IgG antibody to H1N1 (pH1N1) virus (A/California/04/2009) failed to protect naïve guinea pigs from infection by transmission with the virus from inoculated partner animals. By contrast, the majority of guinea pigs immunised with an IgA construct at a dose sufficient to detect the antibody in nasal washes were protected. They concluded that the expression of sufficient neutralising antibodies at the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory tract is more important than serum IgG in preventing influenza transmission by respiratory droplets.

This anatomical and immunological setting is invaluable in our understanding of the influence of nutrition on upper respiratory tract influenza infection and transmission – a setting, as will be described later, that can inform our understanding of the protective interplay between nutrition and nasopharyngeal immune function in COVID-19.

Do IgA antibodies play a primary role in preventing influenza virus infection in the upper respiratory tract?

Evidence supporting a key role of secreted IgA antibodies to influenza virus as a fundamental platform in preventing upper respiratory tract infection. Observations which resonate powerfully with mucosal immune defence and nutritional interactions discussed earlier and include the following:

-

In a double-blind placebo-controlled vaccination study Belshe et al.(Reference Belshe, Gruber and Mendelman78) demonstrated that nasal administration of a live attenuated cold-adapted trivalent influenza vaccine was associated with a high correlation of nasal wash IgA and protection from H1N1 challenge. The vaccine displayed 83% efficacy in preventing H1N1 virus shedding after challenge. Mohn et al.(Reference Mohn, Brokstad and Pathirana79) followed the mucosal and humeral responses in tonsils and saliva after intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccination in children, and in addition to the increase in salivary IgA to influenza A(H3N2) and influenza B virus, there was an augmented influenza virus-specific B-cell response in tonsils.

-

Abreu et al.(Reference Abreu, Clutter and Attari80) conducted a 3-year longitudinal study in young adults and the elderly following influenza vaccinations where they found a positive relationship between vaccine-induced IgA antibody titres and traditional immunological endpoints.

-

Suzuki et al.(Reference Suzuki, Kawaguchi and Ainai81) demonstrated that intranasal administration of inactivated influenza vaccines produced multiple molecular forms of neutralising antibodies in human nasal mucosa. These comprised at least five quaternary structures and a polymeric form, which had a higher neutralising potency against seasonal influenza viruses (H3N2) and the highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (H5N1). They concluded that the large polymeric sIgA has a critical role in protective immunity against influenza virus infection of the human upper respiratory tract(Reference Suzuki, Kawaguchi and Ainai81). Terauchi et al.(Reference Terauchi, Sano and Ainai82) demonstrated that in nasal wash samples, multimeric IgA correlated with virus neutralising titres, suggesting multimeric IgA antibodies have an important role in nasal mucosa antiviral activity.

-

Quinti et al.(Reference Quinti, Mortari and Salinas16) showed the significance of IgA in studies with patients with primary antibody deficiencies, whereby the impaired production and antibody-mediated response with IgA is associated with respiratory infections.

-

In a comprehensive review, Tamura et al.(Reference Tamura, Ainai and Suzuki63) indicated that the respiratory tract mucosa is both the site of influenza infection and immune response. Secretory IgA neutralises the influenza virus with subsequent transportation to the apical surface of the epithelium with subsequent processing, preventing upper respiratory tract infection. This is in contrast to serum IgG antibodies that play a role in preventing progression to lethal influenza induced pneumonia. A conclusion consistent with Renegar et al.(Reference Renegar, Small and Boykins83), who suggested that IgA mediates protection in the nasal compartment and IgG provides the dominant protection in the lung. Likewise, Chen et al.(Reference Chen, Magri and Grasset84) drew attention to the lower abundance of IgG compared with IgA in the upper respiratory tract and gut mucosa, as well as the mammary and lachrymal glands.

Enteral feeding mediates upper respiratory tract anti-influenza protection

As mentioned earlier, a critical lesson from studies on enteral feeding was the relationship with respiratory immunity. The extent to which this relationship is present with influenza infection is fundamental in understanding the protective role of food/nutrition working in concert with mucosal immune function. The following studies focused on influenza immunity, and support a protective role of enteral feeding when contrasted to parental feeding:

-

Kudsk and Renegar(Reference Kudsk, Li and Renegar31), using mice inoculated with mouse-specific influenza virus, demonstrated that IgA-dependent upper respiratory tract immunity was preserved with enteral feeding but not with intravenous feeding.

-

Renegar et al.(Reference Renegar, Johnson and Dewitt85) showed that parenteral nutrition in immunised mice reduced influenza-specific IgA in nasotracheal washes and depressed the selective transport index, indicating impaired mucosal transport of polymeric IgA. They concluded that gut associated lymphoid tissue atrophy and impaired transport occurred in the absence of enteral feeding and highlighted the importance of production in respiratory tract IgA-mediated immunity.

-

Nasal anti-influenza immunity loss occurred with parenteral nutrition (TPN) fed immune mice, together with a decrease in influenza-specific secretory IgA in the upper respiratory tract(Reference Renegar, Small and Boykins83). Anti-influenza mucosal immunity was maintained in studies with oral feeding. This finding is consistent with the gastrointestinal lymphoid tissue atrophy discussed earlier.

-

Fukatsu and Kudsk(Reference Fukatsu and Kudsk86) demonstrated in animal experiments that the defence against H1N1 influenza virus was with the IgA immunity, and animals fed via the gastrointestinal tract maintained this immunity, whereas animals fed parenterally lost this established immunity.

Neonatal feeding and influenza protection

Schlaudecker et al.(Reference Schlaudecker, Steinhoff and Omer87) summarised that secretory IgA is the most abundant immunoglobulin in breast milk on the basis of studies in women vaccinated against pertussis, rotavirus and measles, showing that secretory IgA is produced. There is accumulating evidence, often based upon the results of experiments with vaccinations, for a potentially protective role of IgA in breast milk in influenza. Examples of this experimentation include the following:

-

In looking at the effect of antenatal immunisation on the levels of specific anti-influenza IgA levels in human breast milk, Schlaudecker et al.(Reference Schlaudecker, Steinhoff and Omer87) proposed that sustained high levels of anti-influenza IgA in breast milk and decreased infant episodes of respiratory illness suggest that breastfeeding may provide local mucosal protection for the infant for at least 6 months.

-

As recently summarised by Pannaraj et al.(Reference Pannaraj, da Costa-Martins and Cerini64) live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) induces nasal secretory IgA in children and adults, with high levels correlating with protection from confirmed influenza. The LAIV was inhaled, resulting in direct stimulation of antigen-recognising cells in the respiratory tract(Reference Pannaraj, da Costa-Martins and Cerini64). By comparing LAIV vaccination with intramuscular vaccination with inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV), Pannaraj et al.(Reference Pannaraj, da Costa-Martins and Cerini64) demonstrated that human milk influenza-specific IgA increased by day 30 and persisted for at least 180 d for both LAIV and IIV. They noted a strong induction of innate pathways with LAIV but not IIV, and thus, it may provide protection against mucosal infections before antigen-specific immunity develops in human milk(Reference Pannaraj, da Costa-Martins and Cerini64).

Decades of research has provided powerful insights into the protective role of the mucosal immune system in collaboration with food and nutrition in protection against infection and transmission. By way of summary, the influenza virus has, through tropism, adapted to infect the upper respiratory tract for infection and transmission. The critical antibody employed in this immune response in the upper airway is IgA and, to a much lesser extent, IgG. This IgA-linked immunity was preserved with enteral but not parental feeding, highlighting the role of gut associated lymphoid tissue and upper respiratory tract viral protection. Importantly IgA is the most abundant immunoglobulin in breast milk.

This invaluable accumulation of decades of knowledge provides a powerful position from which to look at the drivers of protection to early infection with SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19. A similarly contagious virus used tropism to target the upper respiratory tract of humans, in this way answering the key question of whether the well-documented properties of mucosal protection for the influenza virus apply to the more recently emerged SARS-CoV-2 virus, mediating COVID-19.

Evidence is accumulating that indicates the nasopharyngeal mucosal barrier is a fundamental target in any consideration of early prevention of COVID-19 involving nutrition, either alone or in combination with intranasal vaccine approaches.

SARS-CoV-2 and the human mucosal immune response

We have built on the observations described above and focused on the mucosa and the immune system in the protection against COVID-19. The mucosa is the initial immunological barrier that utilises the principal antibody, IgA, at different anatomic sites(Reference Yan, Lamm and Bjorling88).

In COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, in a similar fashion to influenza virus, has through tropism adapted to infect the upper respiratory tract of humans for infection and transmission. Accordingly, it is therefore possible with SARS-CoV-2 to address and compare the four key domain areas described for the influenza virus above, namely:

-

The upper respiratory tract as the site of initial SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

-

The role of IgA antibodies in COVID-19.

-

The role of enteral feeding and SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

-

The role of neonatal feeding and SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

In this way, despite their differing viral nature it can be recognised that both viruses share a common vulnerability at the point of host entry, and as such, a common nutrition-based approach to enhancing mucosal immune defence mechanisms could be applied to reduce transmission and infection.

The upper respiratory tract is the site of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection and transmission

-

Soffritti et al.(Reference Soffritti, D’Accolti and Fabbri89) detected a mucosal IgA response in 64% of patients with COVID-19 and found that the anti-SARS-CoV-2 sIgA was more abundant in the asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic patients with COVID-19, with a decreased mucosal sIgA response seen in more severely symptomatic patients. They highlighted the importance of this local immune response in early control of infection, and that sIgA may be of importance in controlling virus penetration into the body.

-

In a longitudinal antibody response study, Fröberg et al.(Reference Froberg, Gillard and Philipsen90) demonstrated that early and higher antibody responses resulted in early viral clearance and symptom resolution. Furthermore, most of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 nasal antibodies, but particularly anti-RBD IgA, correlated with disease symptom resolution.

-

In a study focused on systemic and mucosal humoral immunity in SARS-CoV-2 convalescent subjects, Butler et al.(Reference Butler, Crowley and Natarajan91) suggested mucosal IgA neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 at the point of entry could be substantial, and together with previous studies, suggested mucosal IgA could be of use as an immune correlate in protection from infection and reduced likelihood of transmission.

-

Based on the view that secretory IgA protects the mucosal surface by neutralising respiratory viruses, Sterlin et al.(Reference Sterlin, Mathian and Miyara92) measured the SARS-CoV-2-specific neutralising antibodies in the serum, saliva and bronchoalveolar fluid in patients with COVID-19. They found that IgA contributed to neutralisation more than IgG, and neutralising IgA was detectable in saliva from 49 to 73 d post-symptoms. They also highlighted that the antibody production is in response to SARS-CoV-2 infecting the mucosal surface, and that SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA dominates as an early neutralising antibody.

-

Semih and Doblan(Reference Semih and Doblan28) examined the effects of tonsillectomy in patients with COVID-19 and concluded that, based on comparative analysis, the risk of symptomatic disease was higher in patients with COVID-19 and a history of tonsillectomy.

-

Van der Ley et al.(Reference van der Ley, Zariri and van Riet93) demonstrated in animals that an intranasal OMV-based vaccine generated high mucosal and systemic immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection. They noted high levels of spike-binding immunoglobulin G (IgG) and A (IgA) antibodies in the nose and lungs. Intramuscular vaccination only induced an IgG response in the serum.

IgA antibodies and prevention of SARS-CoV-2 virus infection in the upper respiratory tract

-

As highlighted by Ejemel et al.(Reference Ejemel, Li and Hou94) the enhanced antigen binding of mucosal IgA in comparison with IgG is due to its multimeric structure and the mucosal surface protected by the high level of glycosylation of IgA antibodies. Wang et al.(Reference Wang, Lorenzi and Muecksch95) demonstrated that the dimeric, secretory form of IgA, found in mucosa, is more than one log more potent than the monomer against SARS-CoV-2. They also state that dimeric IgA is a more potent neutraliser than IgG.

-

In experiments conducted some years ago, evaluating protection against SARS coronavirus using an inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine with an adenovirus-based vector expressing the nucleocapsid, See et al.(Reference See, Zakhartchouk and Petric96) demonstrated that an intranasal but not intramuscular route of administration restricted SARS-CoV replication in the lungs. More recently, Langel et al.(Reference Langel, Johnson and Martinez97), using an adenovirus vector SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that expressed the spike protein, demonstrated that both intranasal and oral administration induced a robust antibody response. Furthermore, when they induced a post-vaccination infection with a SARS-CoV-2 challenge the intranasal or oral vaccinated hamsters had decreased viral RNA and infectious virus in the nose and lungs, with less lung pathology compared with mock-vaccinated control hamsters. Similar results were seen in work by Langel et al.(Reference Langel, Johnson and Martinez97) and King et al.(Reference King, Silva-Sanchez and Peel98) – the latter showing that even a single intra-nasal vaccination with a adenovirus type 5-vectored vaccine (encoding the receptor-binding domain of SARS-CoV-2) in mice produced a strong and sustained mucosal IgA response in the respiratory tract that offered protestation from a lethal SARS-CoV-2 challenge.

-

Quinti et al.(Reference Quinti, Soresina and Guerra99) in studying patients with primary antibody deficiencies identified a clinical phenotype with high pneumonia risk, patients who had low IgG and IgA. Subsequently, this group(Reference Quinti, Mortari and Salinas16) highlighted the importance of impaired IgA production and responses, as well as the susceptibility to respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, upper respiratory tract colonisation and the risk of chronic respiratory diseases development. Their work suggested that a lack of anti-SARS-Cov-2 IgA and secretory IgA (sIgA) might be a cause of COVID-19 severity, vaccine failure and prolonged viral shedding.

-

Çölkesen et al.(Reference Colkesen, Kandemir and Arslan100) highlighted the role of mucosal immunity as an initial barrier to a pathogen’s entry into the body and that immunoglobulin A (IgA) is the key antibody responsible for mucosal immunity. In looking at the relationship between selective IgA deficiency and COVID-19 prognosis, they found that the risk of severe COVID-19 in patients with selective IgA deficiency was approximately 7.7-fold higher than that in other patients.

-

Intriguingly, Naito et al.(Reference Naito, Takagi and Yamamoto101) have proposed a potential association between the incidence of selective IgA deficiency in various countries and COVID-19 cases based on a comparison of COVID-19 by country and associations with IgA deficiencies.

-

In examining responses of health care workers to SARS-CoV-2, Hennings et al.(Reference Hennings, Thorn and Albinsson102) found that contracting the virus was associated with SARS-CoV-2 neutralising IgG in serum whereas the IgA responses while partially neutralising were present in individuals who did not succumb to COVID-19 and who reported symptoms or had PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. The authors suggest that the IgA measured in the study may be a surrogate marker for nasal IgA which exerts protection from COVID-19 by preventing viral entry to the human.

Enteral feeding with upper respiratory tract SARS-CoV-2 infection

-

Overall, there are few data available on the outcomes of feeding practices in patients with COVID-19 disease (Karayiannis et al.(Reference Karayiannis, Kakavas and Bouloubasi103)). In a review based on case reports, retrospective clinical studies, review articles and society recommendations, Aguila et al.(Reference Aguila, Cua and Fontanilla104) commented that enteral nutrition is a preferred nutrition strategy if oral intake fails, as the lack of nutrient contact with the mucosa may result in lymphoid tissue atrophy and a decline in immune efficiency. In a subsequent review, Ojo et al.(Reference Ojo, Ojo and Feng105) demonstrated that early enteral nutrition reduced mortality in critically ill patients with COVID-19 disease but not the length of hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) stay compared with delayed enteral or parenteral nutrition. However, in a study by Karayiannis et al.(Reference Karayiannis, Kakavas and Bouloubasi103), enteral nutrition was not superior to parenteral nutrition in terms of mortality but may be associated with reduced length of stay in hospital and stay in mechanical ventilation support for the critically ill. No improved outcomes with the initiation of enteral nutrition within 24 h with mechanically ventilated adults with COVID-19 was reported by Farina et al.(Reference Farina, Nordbeck and Montgomery106).

Neonatal feeding and SARS-CoV-2 protection

The presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA antibodies in human milk include the following observations in addition to those above in women vaccinated with non-COVID-19 vaccines.

-

Pace et al.(Reference Pace, Williams and Jarvinen107) found that breast milk from women with COVID-19 does not contain SARS-CoV-2 but is a likely lasting source of immunity mediated by IgA specific to the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein receptor binding domain.

-

Fox et al.(Reference Fox, Marino and Amanat108) indicated the presence of SARS-CoV-2 IgA in the milk of COVID-19-recovered participants with 89% of the samples positive for spike-specific IgA. They also suggested that the highly durable titres may be due to long-lived plasma cells in the GALT and/or mammary gland, as well as continued antigen stimulation.

-

Perl et al.(Reference Perl, Uzan-Yulzari and Klainer109) demonstrated secretion of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk for 6 weeks after vaccination with IgA secretion seen as early as 2 weeks. Based upon the strong antibody neutralising effects, there is a suggestion of potential protection against infection in the infant.

-

Valcarce et al.(Reference Valcarce, Stafford and Neu110) explored the presence of SARS-CoV-2-specific immunoglobulins in human milk after the COVID-19 vaccination. They showed that the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines induce SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA and IgG secretion in human milk.

-

Selma-Royo et al.(Reference Selma-Royo, Bauerl and Mena-Tudela111) examined the time course of SARS-CoV-2 induction of specific IgA and IgG in breast milk after vaccination and found that both IgA and IgG increased at 2 weeks after the first dose of mRNA vaccines. In addition, they found the levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA and IgG were dependent on the vaccine type.

Exploiting the long history of nutrition in revealing the pillars of mucosal immunity as well as the commonality in the upper respiratory tract mucosal with SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus provides a powerful argument for enhancing mucosal immune function with nutrition in COVID-19.

It is apparent that anti-SARS-CoV-2 secretory IgA (sIgA) was more abundant in asymptomatic or pauci-symptomatic patients with COVID-19 and that higher antibody responses resulted in early viral clearance and symptom resolution. Furthermore, it is possible that mucosal IgA neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 at the point of entry is substantial, that SARS-CoV-2 infects the mucosal surface and that SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA dominates as an early neutralising antibody.

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 IgA in breast milk of COVID-19-recovered participants was seen in 89% of samples from women positive for spike-specific IgA(Reference Fox, Marino and Amanat108). Secretion of SARS-CoV-2 specific IgA and IgG antibodies in breast milk occurred for 6 weeks after vaccination, with IgA secretion seen as early as 2 weeks after vaccination(Reference Selma-Royo, Bauerl and Mena-Tudela111). In addition, the mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccines induce SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA and IgG secretion in human milk(Reference Valcarce, Stafford and Neu110). It seems that the mucosal antibody IgA has a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection; key aspects of this research are summarised above.

Decades of research have provided powerful insights into the protective role of the mucosal immune system in concert with food and nutrition in the protection against infection and transmission. We have provided a detailed comparison of the role of the mucosal immune protective function for protection against SARS-CoV-2 and influenza A infection. It is apparent that, despite the structural differences in the two viruses, their attack upon the upper respiratory tract is countered by a common mucosal protective barrier, with IgA playing a lead role in that process.

The interplay between viral tropism, convergent evolution and human adaption defines the food and nutrition-based strategy to protect against SARS-CoV-2 infection

In studying the comparative evolution of nutrition and immunity, the lessons derived from polio research in regard to mucosal immunity, the clinical significance of enteral feeding and respiratory function and the mucosal protection present in maternal feeding all indicate a fundamental role of human mucosal function in pathogen protection. The real-life insights to this protective role appear in the powerful similarity of the mucosal response to the influenza virus and to the more recent SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

The viruses responsible for the two largest pandemics seen in the past 100 years belong to two distinct viral classifications and, with progression to serious diseases, display differing pathophysiological outcomes. However as can be seen from the preceding discussion, there is a remarkable similarity between both viruses in the human response; they generate at the very first entry to humans by crossing the nasopharyngeal mucosal layer (Figure 2). Thus, while both viruses independently seek to enhance their propagation through upper respiratory tract infection, human evolution has refined a mucosal immune barrier to offset the earliest stages of this viral infection.

Fig. 2. Commonality in the upper respiratory tract infection and the mucosal vulnerability of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses. The images of the COVID-19 and influenza viruses used in this figure were developed by the US Centres for Disease Control (CDC). Our use of the virus images does not imply endorsement by CDC or the US Government of this manuscript, the authors or their organisations. The virus images are available on the CDC website for no charge.

It is this interplay between tropism, convergent evolution and human adaption that defines a food- and nutrition-based strategy to support protection against severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Strategies to support vaginal delivery, breastfeeding to 6 months, the potential use of intranasal vaccine routes of administration, and appropriate nutrition to support the microbiome appear to be important considerations in health policy.

Against this background, the opportunity arises to build on experiences encountered with human influenza infection by identifying nutritional strategies for enhancing mucosal immune function to protect against COVID-19 and reducing its clinical severity.

Food and nutrition influence the risk and severity of infection in COVID-19

The interplay between viral tropism, the consequences of convergent evolution, and human adaptive responses defines the food- and nutrition-based strategies to aid in the protection against infection with SARS-CoV-2. Not surprisingly, there is a growing body of literature on the relationship between food and nutrients and the risk and severity of COVID-19.

The importance of nutrition relates to its ability to modulate immune responses during infectious disease, with evidence that a range of nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, flavonoids and fatty acids, may reduce the risk of chronic pulmonary diseases and viral infections(Reference Gozzi-Silva, Teixeira and Duarte58,Reference Calder67) . Rodriguez-Leyva and Pierce(Reference Rodriguez-Leyva and Pierce6) have drawn focus to nutritional status in modulating infectious disease and susceptibility to COVID-19, with malnutrition predisposing to infection in disadvantaged populations and the elderly. Furthermore, a series of articles focused on the nutritional aspects of this disease have been summarised by Mathers(Reference Mathers7). These papers drew attention to avoiding nutritional deficiencies, the importance of the gut microbiome and the nutritional maintenance of innate and adaptive immunity. The significance of the interaction of nutrients (for example, vitamins A, C, D and E) in support of the immune system in the context of respiratory infections was also highlighted(Reference Kim, Rebholz and Hegde112). Pecora et al.(Reference Pecora, Persico and Argentiero113) emphasised the importance of micronutrients, including several vitamins and trace elements involved in immune support, and emphasised that deficiencies in some of these micronutrients affect components of adaptive immunity and antibody-mediated humoral responses. Collectively, there is broad agreement concerning the importance of the relationship between nutrition and immunity on the modulation of COVID-19.

An additional area of importance in considering the risk and severity of COVID-19 relates to diet quality. In a very comprehensive study, Merino et al.(Reference Merino, Joshi and Nguyen114) conducted a prospective analysis of the association of diet quality, risk and severity of COVID-19 and its intersection with socioeconomic deprivation. Of importance was the finding in this study that a diet composed of healthy plant-based foods lowered the risk and severity of COVID-19, and this was evident for individuals living in areas with higher socioeconomic deprivation. Consistent with these findings, Kim et al.(Reference Kim, Rebholz and Hegde112), in a study on health care workers from six countries, concluded that plant-based diets or pescatarian diets were associated with lower odds of moderate-to-severe COVID-19.

Motti et al.(Reference Motti, Tafuri and Donini115) identified a relationship between immune function and vitamins C and D. Likewise the plant (citrus)-based flavonoid hesperidin in addition to displaying anti-inflammatory properties(Reference Khorasanian, Fateh and Gholami116) also possessed immunoregulatory properties and, importantly, has been shown in animal studies to increases intestinal IgA(Reference Camps-Bossacoma, Franch and Perez-Cano117). In summary, those foods and nutrients that maintain an effective immune response would appear to offer a sound approach to protection against COVID-19.

The role of nutrients in optimising mucosal protection involving IgA in COVID-19

As emphasised by Quinti et al.(Reference Quinti, Mortari and Salinas16), IgA protects epithelial barriers from pathogens and an early SARS-CoV-2 specific response is dominated by IgA antibodies contributing to virus neutralisation. Sterlin and Gorochov(Reference Sterlin and Gorochov118) drew attention to IgA being potently active against several pathogens, including rotavirus, poliovirus, influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. As summarised by Kheirouri and Alizadeh(Reference Kheirouri and Alizadeh119), decreased or absent IgA has been considered as a clinically significant immunodeficiency leading to a susceptibility to infections and recurrent mucosal infectious diseases including recurrent otitis media, upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and pneumonia. It follows that nutritional optimisation of early mucosal protection in COVID-19 must involve an understanding of what foods and nutrients are important in maintaining the effectiveness of mucosal IgA in its polymeric and secretory forms. The following discussion identifies those nutrients and foods that are reported to interact with mucosal IgA.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is a steroid hormone that is produced endogenously through the effect of ultraviolet light on the skin or can be consumed in some foods or supplements. Vitamin D plays various roles in immunomodulation, and a meta-analysis has demonstrated that it is effective in preventing acute respiratory infections(Reference Martineau, Jolliffe and Hooper120). More recently, a potential role for vitamin D in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and progression and severity of COVID-19 was reviewed by Ali(Reference Ali121). In that review, it was pointed out that vitamin D had been shown to increase mucosal secretion of anti-viral peptides, which may improve mucosal defences. Furthermore, a significant negative correlation was found between mean serum vitamin D levels and COVID-19 cases per one million inhabitants in European countries, but there was no relationship with COVID-19 death rates. This suggests that vitamin D might be associated with an improved ability to reduce infection rate, rather than to reduce the impact of the disease once infected, perhaps due to effects of vitamin D on improving mucosal immunity.

In a meta-analysis of randomised control trials (RCT), Zhu et al.(Reference Zhu, Zhu and Gu122) showed that vitamin D supplementation could be effective in preventing influenza. Furthermore, Pecora et al.(Reference Pecora, Persico and Argentiero113) concluded that there was a role for vitamin D in regulating the response to viral infections and that most observational studies confirmed an association between increased susceptibility to respiratory infections and lower vitamin D levels. Consistent with that view, He et al.(Reference He, Handzlik and Fraser123) demonstrated that athletes with low vitamin D status may have a higher risk of URTI and suffer more severe symptoms; this may be due to impaired mucosal and systemic immunity, including reduced secretory IgA. It is important to note that there is a constant interaction between the mucosal lymphoid tissue which adaptively produces mainly polymeric IgA (pIgA) and the epithelium, with the majority of pIgA in secretions of epithelial origin in the form of secretory IgA (SIgA)(Reference Pilette, Ouadrhiri and Godding124). As summarised by Ashique et al.(Reference Ashique, Gupta and Gupta125), vitamin D defence against infections related to the respiratory system has been demonstrated in randomised clinical trials and meta-analyses which suggest an association of COVID-19 cases with abnormally low vitamin D levels. Panagiotou et al.(Reference Panagiotou, Tee and Ihsan126) showed that low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 are associated with greater disease severity. By contrast, an analysis of UK Biobank data did not support a potential role for 25(OH)D to explain susceptibility to COVID-19 infection(Reference Hastie, Mackay and Ho127).

Vitamin A (retinol, retinoic acid)

Vitamin A regulates genes involved in immunity and the production of antibodies, enhanced through the interaction of vitamin A and T helper cell development(Reference Pecora, Persico and Argentiero113). Importantly, Gozzi-Silva et al.(Reference Gozzi-Silva, Teixeira and Duarte58) drew attention to studies showing that retinoic acid is essential to producing IgA antibodies. It may also promote immunoglobulin class switching to increase IgA production in B cells(Reference Correa, Portilho and De Gaspari128).

It was demonstrated earlier that vitamin A deficiency impairs the secretory IgA response to influenza infection(Reference Stephensen, Moldoveanu and Gangopadhyay129). As summarised by Pecora et al.(Reference Pecora, Persico and Argentiero113), vitamin A supplementation correlates with a reduction in infection-related morbidity and mortality that is associated with vitamin A deficiency. Mucosal IgA responses towards viruses and viral vaccines are impaired in the gut and the upper respiratory tract as well as intranasal vaccination, failing to induce normal levels of IgA in vitamin-A-deficient animals(Reference Surman, Jones and Rudraraju130,Reference Surman, Jones and Sealy131) . This impaired intranasal vaccine response was corrected with a single intranasal application of retinyl palmitate with the vaccine. In raising the possibility of vitamin A being a potential protective factor with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Wang et al.(Reference Wang, Zhang and Wu132) highlighted that retinoic acid can mediate the production of SIgA in the respiratory tract.

Probiotics

In an early study by Kaila et al.(Reference Kaila, Isolauri and Soppi133), it was shown that children with acute rotavirus, when treated with a lactobacillus preparation (Lactobacillus GG), had a non-specific humoral response during the acute phase of the infection, and at convalescence 90% of the study group (compared with 46% of the placebo group) had developed an IgA-specific antibody-secreting response to rotavirus. Subsequently, Vitiñi et al.(Reference Vitiñi, Alvarez and Medina134) showed that lactic acid bacteria (LAB) were able to increase the number of IgA-producing cells associated with the lamina propria of the small intestine. In a double-blind randomised study, Pahumunto et al.(Reference Pahumunto, Sophatha and Piwat135) showed that the probiotic Lactobacillus paracasei SD1 increased salivary IgA and reduced Streptococcus mutans. Mardi et al.(Reference Mardi, Kamran and Pourfarzi136) emphasised the enhanced mucosal protection of probiotics by increased IgA levels, that immunomodulatory benefits may be crucial for people at risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2. Collectively highlighting the significance of the gut–lung axis in the disruption of respiratory diseases, Brahma et al.(Reference Brahma, Naik and Lordan137) have drawn attention to promising but limited evidence to suggest that probiotics are an effective prophylactic or treatment strategy for COVID-19 and the importance of the microbiome as a potential target in COVID-19.

Zinc

In a comprehensive study on the efficacy of micronutrients in supporting immunity, particularly with respect to respiratory virus infections, Pecora et al.(Reference Pecora, Persico and Argentiero113) drew attention to the role played by zinc in the essential maintenance of membrane barrier integrity in the pulmonary and intestinal epithelia and their role as the first barrier in pathogen protection. Li et al.(Reference Li, Luo and Liang138) conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on trace element status (Zn, Fe, Cu, Mg and Se) in COVID-19 and the relationship between circulating trace elements and COVID-19 severity and survival status. They found that Zn concentrations in patients with COVID-19 were significantly lower than controls and correlated with disease severity. In a population-based study, before vaccination was available and when the initial viral variant was circulating, Equey et al.(Reference Equey, Berger and Gonseth-Nusslé139) demonstrated that low plasma Zn concentrations were associated with higher anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG and IgA seropositivity. Kheirouri and Alizadeh(Reference Kheirouri and Alizadeh119) reported that zinc and vitamin A modulate many immune responses, including antibody synthesis and secretion, and that vitamin A deficiency was associated with lower mucosal concentrations of IgA. In this context, it is of interest that Levkut et al.(Reference Levkut, Husáková and Bobíková140) demonstrated that, in chickens, zinc supplements increased the expression of the IgA gene and the levels of intestinal IgA.

Bovine colostrum