INTRODUCTION

In a memorial to his successor composed in the 1620s, Peruvian viceroy Francisco de Borja y Aragón (1581–1658), the prince of Esquilache, offered his opinion on a long-standing debate regarding the construction of ventilation shafts at the mercury mine of Huancavelica. Located in the Andean highlands in what today is modern Peru, Huancavelica was one of the early modern world’s principal sources of mercury whose cinnabar (red mercuric sulfide) had been mined by the area’s Indigenous inhabitants before its incorporation into the Incan empire at the turn of the fourteenth century and, subsequently, by the Spanish in the sixteenth.Footnote 1 Borja y Aragón described the state of the mine in the following terms:

So that your excellency understands the great danger and little benefit of the vents for the upper part, it must be imagined that the cerro of Huancavelica is not very high and its form is like a hat that is tipped over. And because of the ventilation shafts given to it, it is pierced in many parts and leads to one of two inconveniences: either these vents aren’t repaired with wood and are put at risk when they are blocked as a result of floods and felled timber, or they are fortified with a great quantity of wood so that they resist the ravages of time…. Accordingly, your majesty should consider the harm that can result from giving two penetrating wounds to this body, already so mistreated, and that the remedy is to load it up with so much wood that the weight alone is enough to exhaust it.Footnote 2

Borja y Aragón closed his description by advising the incoming viceroy to consider the “harm” that would result from giving two further “penetrating wounds” to this “body,” which was already so “mistreated,” that the only “remedy” was to load it up with so much wood that the weight alone would “exhaust it.” This portrayal of Huancavelica as on the brink of collapse was intended to convey Borja y Aragón’s preference for a system of horizontal, rather than vertical, ventilation shafts. To further this argument, he noted that in addition to the difficulties he just outlined, such vertical ventilation shafts would not allow the lower part of the mine to “be ventilated and breathe.”

Today we tend to describe Huancavelica as a site that produces the natural resource of mercury, where natural resource and mercury are terms with precise meanings in relation to modern scientific principles. Borja y Aragón’s contemporaries, however, tended not to use the term resource in connection with mercury. Instead, as explored in greater detail below, mercury—like other metals—was often described as a tesoro (treasure) or source of riches. It was part of the royal hacienda, a word we might today tend to gloss as treasury, though the hacienda and the tesoros, or riches, of the New World consisted not only of the mercury in the mine but also of Huancavelica itself—the mercury mine. These riches were described as contributing to the common good by sustaining the realm. Mercury and other minerals were often likened to plants and agricultural crops: they were endowed by nature with generative properties. Nature was portrayed as actively thwarting human attempts to access mineral riches, though nature itself was described as an entity that did not own or make good use of these mineral riches.Footnote 3

Similarly, we might be tempted to use the term landscape to describe the visual depiction Borja y Aragón offered his successor to help him envision the difficulties facing Huancavelica. Landscape, in this sense, conforms to the modern conception of a natural environment shaped by human activity. However, the relationship between humans and nature as described by the viceroy does not conform to modern, Western conceptions. In Borja y Aragón’s report, Huancavelica is portrayed as a living body that has been wounded by human activity. It strains under the burden of the wooden supports that are necessary to counteract these penetrating wounds. Its metallic ores produce exhalations, which in period sources are described as contributing to miners’ ill health; to prevent inhalation of these noxious fumes, the mine must be ventilated so that it, like the workers who crawl through its underground spaces, are able to “breathe.”

This special issue aims to critically examine conventional understandings of the terms resources and landscapes by interrogating their modernist and Western-centric interpretations through a historical lens. It calls into question the widespread employment of these terms in the humanities and proposes an alternative heuristic framework to develop historically specific and contextual understandings of the way early modern and non-Western actors envisioned the entanglement of nature’s materiality and human society. By embracing the complexities and contradictions that emerge, we seek not only to challenge existing paradigms but also to enrich contemporary discussions in scholarship in the humanities, particularly in the context of the Anthropocene. Our exploration is guided by questions about the relevance of premodern studies, the integration of historical perspectives with present concerns, and the potential of diverse disciplinary and geographical approaches.

APPROACHING THE PAST THROUGH THE CONCERNS OF THE PRESENT

Borja y Aragón’s vision of Huancavelica as a living body violated, weighed down by scaffolding, and struggling to breathe is likely unfamiliar to most modern readers. Their vision has instead been shaped by scholarship that has tended to approach Huancavelica through the lens of modern analytical categories, including the environment, technical knowledge, and human and natural resources. In this guise, Huancavelica has been portrayed as emblematic of the promises and pitfalls of colonialism, environmental degradation, and modernity.

For economic and world historians, Huancavelica is notable for its position at the center of the creation of early modern global markets and the worldwide circulation of people, natural materials, and material goods. The discovery of new silver deposits in Iberian-controlled American territories transformed and connected regional economies of silver trade centered on deposits in Central Europe and Japan. The high production levels of American mines led to a surge in the global supply of silver, the effects of which—including sustained inflation in Europe and commercial intensification in Ming China—were regarded with unease by period actors.Footnote 4

Historians of technology, however, have focused on the fact that this production boom was facilitated by new technologies. Chief among these developments was the patio process, a method of refining silver via amalgamation with mercury first implemented on a large scale in New Spain in the 1550s. Although mercury was vital to the processing of American silver, its known sources were limited in the early modern period. Huancavelica was the main supplier of mercury for nearby Potosí (modern Bolivia), which produced over half the world’s silver from 1545 to the 1650s.Footnote 5 Almadén, located in the Iberian Peninsula and mined since antiquity, served as the other primary source for the Iberian empire. Mercury was also mined at Idria (present-day Slovenia) and Monte Amiata (Tuscany) and could be obtained from China, where cinnabar had been mined since the Shang dynasty.Footnote 6

Environmental historians, by contrast, center Huancavelica’s geographical position and natural features. They note that the town of Huancavelica is 3,700 meters above sea level in the Andes Mountains of modern Peru southeast of Lima. At the height of production in the late 1570s, it relied on the coerced labor of around three thousand Indigenous Andeans to produce upward of 138,000 kg of mercury per year, which would have facilitated the production of approximately 100,000 kg of refined silver.Footnote 7 The extraction, refining, and transport of mercury, modern scholars argue, contributed to chronic mercury toxicity in the surrounding regions.Footnote 8

Historians of labor and colonialism, in turn, focus on how the Iberian state administered its natural and human resources to exploit its mineral deposits using the new refining technologies. By law, miners were required to turn over one-fifth of the silver they produced to the Crown. The activities of mining and refining at Huancavelica, Potosí, and nearby mines were dependent on the contributions of Indigenous laborers drafted into service under a coercive labor regime (mita) instituted in the late sixteenth century.Footnote 9 In addition, the Crown established administrative oversight over the production, transport, and sale of mercury, both to augment its own revenues and to ensure adequate supply for the silver industry.Footnote 10

This modern analytical lens is not unique to Huancavelica. Studies of mining activities in key regions of early modern Europe, for example, often employ a perspective that credits seemingly forward-looking technological and economic developments with the area’s fifteenth-century mining boom.Footnote 11 Such narratives emphasize the introduction of expensive water drainage and ventilation systems, along with the adoption of the Saigerverfahren—a specialized smelting technique that separated silver from copper-rich ores using lead as a solvent—as pivotal innovations that enabled extraction from deeper geological deposits in the Ore Mountains, Harz Mountains, Carpathians, and Tyrolean Alps. Scholars have also highlighted how the capital necessary for these costly mining endeavors was raised through the introduction of specific mining shares called Kuxen (singular Kux, plural Kuxen). This early modern financial instrument differed from modern stocks: after the initial purchase at a fixed price, investors known as Gewerken were required to contribute additional funds on a quarterly basis to finance workers’ wages, equipment, consumables, and technological infrastructure.Footnote 12 In return, the Gewerken stood to gain quarterly profits if yields were favorable. Shifting focus from technological and financial innovations to social structures, social historians have examined working conditions and migration patterns within these mining communities. Their explorations of the evolution of mining settlements often proceeds with an implicit aim of tracing the origins of current demographic and economic configurations. This teleological approach inadvertently assigns agency to economic and technological developments, contributing to narratives in which the complex social, environmental, and cultural dimensions of mining are overshadowed by a focus on progress and modernization.

The impulse to approach historical mining from a presentist perspective applies to other aspects of nature’s materiality. The unfolding global environmental crisis and the introduction of the concept of the Anthropocene have only encouraged this tendency to rely on modern conceptual categories to explore the historical past. The term Anthropocene was proposed in the 2000s by Nobel Laureate and atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen, who argued that the dramatic transformations wrought on the earth system as a result of human activity were unprecedented and should be approached as a new geological epoch.Footnote 13 With the term, Crutzen intended to convey the notion of this “human-dominated, geological epoch” that follows the Holocene, the warm period of the last ten to twelve millennia.Footnote 14

These contemporary concerns have steered historical inquiry toward the frameworks of the modern age. Humanities scholars and scientists alike stress the importance of considering the current climate crisis in relation to Earth’s deep past. However, this past has not been approached on its own terms. Instead, alarm over our present predicament and a growing consensus that the mid-twentieth century marked the identifiable beginnings of the Anthropocene have encouraged scholars to turn to the historical past with the questions and methods of the present.Footnote 15

The way modern scientific concepts and frameworks have been imposed on humanities scholarship is evident in attempts to reexamine the history of early modern mining in response to the current global environmental crisis. These studies have adopted perspectives and methodologies from contemporary environmental science and chemistry, often reinterpreting historical mining practices through the lens of current scientific understandings. Consequently, European and colonial American mining activities are now frequently analyzed for their role in causing extensive deforestation, which is viewed as leading to “erosion, aridification, and the subsequent development of scrub and grassland ecologies.”Footnote 16 Furthermore, the extraction and processing of ores are scrutinized for producing what modern environmental science defines as contaminants—such as heavy metals, mercury, sulphur dioxide, and sulphuric acid. These contaminants, identified and quantified through modern techniques, are noted for their dispersion across ecosystems via waterways, soil, and the atmosphere, and are recognized for their persistent health risks today.Footnote 17 Such studies, while valuable, often frame historical mining activities strictly within the paradigms and priorities of contemporary environmental concerns, potentially sidelining historical contexts and interpretations that diverge from modern scientific narratives.

In seeking to center early modern conceptual frameworks, this special issue is in dialogue with recent literature that has challenged this scientifically inflected approach to historical analysis. In his Inscriptions of Nature, Pratik Chakrabarti revisits the European discovery of deep time to demonstrate the way that the links between history and nature that permeate modern historical writing from the Annales tradition, environmental history, and Anthropocene studies are a product of the European discovery of deep time in the nineteenth century. Through an analysis of the geological and antiquarian investigations that accompanied the nineteenth-century construction of the Yamuna (Doab) canal in northern India, Chakrabarti exhorts scholars in the humanities to resist the urgency that undergirds recent scholarship on the Anthropocene to collapse distinctions between natural and human history and privilege scientific explanations of the past over the historical. Instead, Chakrabarti urges them to recognize that nature itself is a “matter of human imagination.” In his words, “what these peoples crossed or inhabited in the Mediterranean, the Karoo, or the Bay of Bengal was not just the sea, the mountains and the desert but their imaginations of these natural worlds and their frontiers.”Footnote 18

This emphasis on contextualized understandings of nature’s materiality resonates with Alexandra Walsham’s work on the spiritual dimensions of premodern environmental relationships. Walsham demonstrates how the Protestant Reformation transformed British and Irish perceptions of the landscape—the wells, springs, stones, and natural formations that had traditionally functioned as sites of healing and divine grace. Her research reveals that early modern actors interpreted nature’s materiality as both evidence of God’s presence and as a contested space for negotiating religious truth.Footnote 19

Other scholars have highlighted the impossibility of abstracting such spiritual concerns in relation to premodern actors’ engagement with the natural world both within and outside of Europe. Monica Azzolini highlights the convergence of naturalistic, religious, and eschatological themes that undergirded the seventeenth-century Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher’s interest in the excavation and extraction of both relics and natural objects. As Azzolini shows, in his Mundus Subterraneus, a text that is often described as contributing to modern scientific understanding of the earth’s interior, Kircher turned to the underworld both literally and figuratively, exploring the earth’s interior as a site of metallic generation and geological activity, as a source of Roman and Christian archeology, and as a source of spiritual reflection on salvation shaped by eschatological writings and period depictions of hell and purgatory.Footnote 20 Similarly, Allison Bigelow demonstrates in her analysis of colonial Iberian mining literature how Indigenous American contributions to early modern metallurgical theory and practice are made visible through linguistic choices that often reflect both Indigenous American practice and underlying cosmological theories.Footnote 21

Bigelow’s work connects to a broader body of research on early modern mining and metalworking from the history of science, knowledge, and art that has convincingly shown how early modern Europeans understood materials through conceptual frameworks linking human bodies, natural materials, and cosmologies. Within this scholarly context, Pamela Smith argues that metallurgical knowledge emerged directly from physical engagement with materials, where the human body served not merely as a production tool but was implicated in knowledge creation through sensory experiences. Metalworkers and miners developed theories through direct bodily interaction, using multiple senses to understand properties of metals and ores. This practical engagement with the material world was thus embedded within cultural frameworks encompassing religious beliefs, social hierarchies, and the interplay between learned and vernacular knowledge systems.Footnote 22

RESOURCE LANDSCAPES AS A HEURISTIC FRAMEWORK

We propose resource landscapes as an alternative heuristic framework for considering early modern entanglements of natural processes with the human practices and belief systems that often sought to control them. This framework is centered on two terms employed ubiquitously in modern environmental and Anthropocene studies that are of key concern to contemporary scientists: natural resources and landscapes, the latter conceptualized as a piece of land and its shaping by human actors. Using the term resource landscapes as a framework acknowledges the value of examining past historical periods to address pressing questions of the present. Yet, as conceptualized in this special issue, this approach necessitates rigorous analysis of historical actors’ own understandings. We must interrogate whether, and in what ways, these historical figures conceived of what we today categorize as resources and landscapes. Rather than imposing anachronistic concepts, this heuristic framework encourages scholars to historicize actors’ own conceptions, thereby recovering what Pratik Chakrabarti has termed past “imaginaries of nature.”Footnote 23

This heuristic framework acknowledges resource and landscape as Western concepts of relatively recent origins whose relationship to historical periods must be interrogated. The term resource is used today in connection with the natural environment and human efforts in relation to production, management, labor, and consumption. These associations, however, were developed in the twentieth century in dialogue with the professionalization and mathematization of economics.Footnote 24 The etymological root of resource goes back much further in history: the Latin verb resurgere, meaning to arise from, to resurrect, to get up, or to recover. Resurgere is composed of the Latin prefix re- (again) and the verb surgere (to rise/arise); as such, it echoes the verb regere (to lead, to govern).Footnote 25 Daniel Hausmann and Nicolas Perreaux have noted the strong biblical resonances of the Latin term resurgere in medieval literature, where it was associated with the resurrection of Christ, with flesh and its corruptible or incorruptible nature, and with the possibility of rising from the dead.Footnote 26 The first vernacular occurrences of resurgere appear in French texts of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries as resorse and in the fifteenth century as ressource, meaning help or aid, specifically the potential use of personal abilities to overcome a crisis and undergo a renewal.Footnote 27 According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the earliest English usage of resource appears in a 1596 translation of Martinus Barletius’s History of George Castriot, referring to the “resource and restitution of the Albanois name and majesty,” directly borrowing from the French ressource. In 1611, Randle Cotgrave’s dictionary defined ressource as “a resource, new spring,” emphasizing the concept of renewal. Additional instances of early seventeenth-century English usage employed the term in the sense of recovery or return, as in Kenelm Digby’s 1644 reference to sailors who “could not hope for a resource” after being shipwrecked.Footnote 28 Only during the second half of the seventeenth century did the modern understanding of resources, in plural, as stocks of natural materials, money, or other material (or immaterial) goods appear.Footnote 29

Like resource, landscape is a term applied widely today to diverse geographical areas and chronological periods. Scholars identify China and Japan, for example, as having highly developed traditions of landscape art and note that European artists’ approaches to garden aesthetics derive from Persian, Arab, and Mughal Indian models. However, landscape is a word of Northern European origin, and its wide deployment to characterize a style of art often fails to address its cultural specificity and historical development. Key contributions by Stephen Daniels, Denis Cosgrove, and Tim Ingold have expanded the conceptual lens through which landscape is understood. They exhort other scholars to view landscape alternately as a “cultural image, a pictorial way of representing or symbolising surroundings,” or from a dwelling perspective.Footnote 30 Their theoretical analyses, while referencing the historical development of the term landscape, focus more on modern applications than on the reconstruction of past worldviews.

The etymology and historical use of the term landscape demonstrate the long-running association between art form, nature, and human intervention embodied in the term, as well as its cultural specificity. Landscape, as the Early Modern Dutch landtschap, entered the vocabulary of European art around 1600, when landtschappen subsequently became a possible specialization for Netherlandish artists. The term was later adopted and adapted in geographically and linguistically specific ways. The English landscape has its roots in the Dutch landschap or German Landschaft, where land signifies a bounded territory defined by its customs and culture and schaft implies the shaping or crafting of a social unity out of disparate elements. European Romance languages instead derive the comparable term for landscape (such as paesaggio, paysage, paisaje) from the Latin pagus, a term employed to refer to an administrative unit of a province.Footnote 31 The etymological root of the word country in Romance languages, pagus derived from the Greek πάγος, meaning fixed or set, or a space with fixed boundaries. Our modern understanding of landscape, in turn, was shaped by nineteenth- and twentieth-century European values connected with the Romantic movement and nationalism.Footnote 32

Employing resource landscapes as a heuristic framework entails approaching early modern entanglements of natural processes, human practices, and belief systems on their own terms. Such an approach responds to recent scholarship that has emphasized the way conceptions of nature and its materiality are historical constructions. Footnote 33. In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European mining regions, for example, local belief systems and material imaginaries shaped period perceptions of processes, including production rates, technologies of extraction, and the development of infrastructure, often defined today in terms of resources.Footnote 34 Alexandra Walsham’s view of landscapes as “dense and complex systems of signs and symbols” imbued with spiritual significance and deeply enmeshed in historical actors’ sociopolitical realities exhorts scholars to consider landscapes not just as physical spaces but as cultural and spiritual entities. Footnote 35. By demonstrating how the Italian apothecary Camilla Erculiani (d. after 1584) merged Aristotelian philosophy, Galenic medical theory, and Christian theology, Lydia Barnett similarly has emphasized the way nature’s materiality was understood in relation to spiritual forces and individual human bodies in early modern Europe.

These spiritual, geohumoral conceptions of the natural world also shaped the way premodern Europeans articulated their understanding of the relationship between nature’s materiality and human communities.Footnote 36 Such conceptions are evident in the Latin terms natio, gens, genus, and stirps, often glossed as nation, people, ethnic identity, linguistic community, or kin group, which were employed in medieval Europe to reflect notions of human difference linked to descent, grounded in geography and climate, and shaped by astrological influences on human physiology. Footnote 37 Surekha Davies has demonstrated how Christian bodies and behaviors were thought to be subject to change under the influence of new geographical spaces and argues that the natures of human souls and intellects and their capacities for improvement were determined through observations of their bodies, behaviors, and environments.Footnote 38 For Mackenzie Cooley, this geohumoral conception of the natural world shaped the way actors in Italy, Iberia, and the Americas conceptualized notions of difference, breeding, and the potential of humans to intervene in the natural world. Footnote 39

Just as Cooley highlights the long history of what we might term eugenic impulses, this special issue draws attention to the complexity, multiplicity, and slipperiness of early modern categories, even when they convey impulses or concepts familiar to us today. By challenging the anachronistic application of contemporary definitions, our conceptualization of resource landscapes not only enriches our comprehension of historical human-nature interwovenness but also underscores the complexity of interpreting past perceptions through present-day conceptual frameworks. The special issue’s contributions prompt critical reflection regarding the legacies of these concepts in shaping current environmental thought and policies. Thus, the framework of resource landscapes serves not merely as a lens to view the past but also as a bridge connecting historical insights with contemporary environmental challenges. This framework aims to facilitate dialogue among scholars across disciplines to further refine and expand this fruitful heuristic.

MINING RESOURCE LANDSCAPES

Mining provides one prism through which to illustrate the heuristic framework of resource landscapes. The case studies that follow are each anchored in a specific text, image, or object that deals with mining in early modern Europe and the colonial Americas. They offer a point of comparison in relation to the individual contributions that comprise this special issue, which address many other aspects of nature’s materiality. In contemporary understanding, minerals and metals are classified as nonrenewable, inorganic substances identified by their physical, chemical, and geological properties. The Oxford English Dictionary’s entry for metal, for example, defines it as a “hard, shiny, malleable material,” like gold or silver, that is of high density, malleable, and ductile.Footnote 40 In contrast, as these case studies reveal, historical actors in early modern European spaces viewed minerals and metal not as passive, inert, nonrenewable materials but as integral parts of broader, generative, and animate landscapes. For these actors, nature’s materiality was entangled with and understood in relation to spiritual forces, the greater cosmos, and individual and corporate bodies. More particularly, this analysis urges scholars to rethink the common tendency to assume an intrinsic opposition between early modern European and non-European actors’ approaches to nature’s materiality. This is in dialogue with recent studies by Allison Bigelow and Mackenzie Cooley, whose explorations of technical scientific vocabularies related to colonial Spanish mining, on the one hand, and of period understandings of animal generation and their application in breeding, on the other, employ a more inclusive approach that calls attention to points of dialogue and convergence between European and Indigenous American conceptions of nature’s materiality.Footnote 41

MINING AND THE WORKS OF HEAVEN AND EARTH

In 1617, the incumbent principal mining official in the Duchy of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, Georg Engelhardt von Löhneysen (1552–1622), published a lavishly illustrated tome that offered a comprehensive compilation of early modern mining knowledge. The volume, adorned with double-sided engravings, featured site-specific details about the Harz Mountains and addressed mineral generation, mining law, mining administration, activity areas, and technological and metallurgical practices and infrastructures. In his text, Löhneysen described how “God creates crevices and passages and works his sulphur and mercury in them as if in a laboratory, then lets one metal grow after the other, or allows it to be revealed by means of exhalations [Witterungen].”Footnote 42 In making this statement, Löhneysen drew on ancient, medieval, and early modern authorities, who similarly described minerals and metals as organic materials.Footnote 43 He intertwined these organic conceptualizations and metaphors with religious interpretations of metals and broader belief systems in ways that revealed how spiritual understandings of the cosmos shaped approaches to mining and refining in early modern Central Europe.

In his publication, Löhneysen highlighted the potential promise and threat of metals in spiritual terms. Drawing on the insights of Johannes Mathesius (1504–65), a sixteenth-century preacher from the Bohemian mining town of Sankt Joachimsthal (today Jáchymov), Löhneysen highlights the inherent uncertainties of mining due to divine providence disrupted by Adam’s Fall. According to his formulation, the entire earth, including subterranean veins of ore and all minerals, became tainted with sin. Consequently, there was no longer certainty, security, or safety in mining; minerals could grow and perish, and miners could strike it rich or be deceived. Extending this analysis, Löhneysen reports that the miners analogize mining to the seductive power of women. He reports that the miners often proclaim that “a beautiful vein and a beautiful woman can cheat fairly well.”Footnote 44 This comparison underscores not only the material value of metals but also their capacity for change and improvement, making them symbols of hope and promise. However, the transformative nature of metals also harbored a threatening aspect, intertwined with worldly vices such as greed, avarice, and lust. Economic and technological rationalities in mining cannot be divorced from the symbolic and moral connotations embedded within religiously grounded theories of matter.Footnote 45

The overlapping financial, biblical, moral, and affective dimensions evident in this account challenge the modern utilitarian concept of resources. As etymological explorations have demonstrated, prior to the eighteenth century, resources were understood within a framework of physical and spiritual renewal or transformation. The term resources integrates connections between the earthly-material and the transcendent-spiritual meanings of matter. Hence, both natural resources and human souls are in a constant state of dynamic change, a process that, in this postlapsarian state, necessitates effort, work, and sweat.

Scholars whose research focuses on areas outside of Europe have noted the way nature’s materiality was similarly entangled with cosmological systems. The influential seventeenth-century treatise Tiangong kaiwu by Song Yingxing (1587–1666) provides a compelling example of such premodern integrated approaches and of the way their richer conceptual frameworks tend to be flattened through modern analytical categories. Tiangong kaiwu was traditionally translated into English as The Exploitation of the Works of Nature, reflecting scholars’ earlier technological and economically determined readings of the work. Underlining the importance of historicizing and contextualizing belief systems, epistemologies, and cosmologies in Ming China, Dagmar Schäfer has convincingly argued for a new translation of the title as The Works of Heaven and the Inception of Things. Schäfer identifies the conceptual foundation underlying the treatise’s technical descriptions as operating through two distinct stages: the natural conditions through which materials develop and transform without human agency, and the subsequent processes by which these materials acquire their final characteristics through limited human intervention. Her analysis captures a philosophical framework that conceived of nature as a living system governed by discernible patterns that humans could interpret and harness for their benefit.Footnote 46

This metaphysical understanding of material transformation finds concrete expression in Song Yingxing’s treatment of pearls and gems, which he described as formed through the interaction of lunar influences and the forces of water. Anna Grasskamp demonstrates how pearl-bearing shells functioned as sacred symbols of material transformation in Chinese culture. They were connected to Buddhist ritual practices and appeared on Ming blue-and-white ceramics with religious significance. These material artifacts reveal the broader cultural resonance of the cosmological principles that Schäfer identified in Song’s treatise.Footnote 47

These resonances continued to shape discussions of minerals and metals in the late-nineteenth century. Shellen Wu has shown that in period debates over the control of China’s immense coal reserves, these mineral resources were consistently referred to as “the natural benefit of heaven and earth” (天地自然之利). In contrast to modern categorizations of resources as renewable and nonrenewable, one 1740 memorial advocating on behalf of mining described coal as a “natural beneficence” that was “inexhaustible” in supply. Wu argues that in Qing China, mineral resources were understood as inexhaustible benefits deriving from nature, tailored to human needs, and yet requiring management by the state.Footnote 48

THE MINE EMBODIED

Nature’s materiality was also conceptualized in relation to cosmic, social, and individual human bodies, themselves subject to God’s influence. In his History of the Imperial Town of Potosí, dated 1756, Bartolomé Arzáns de Orsúa y Vela (1676–1736, hereafter Arzáns) described how the silver mountain of Potosí in the Andean highlands attracted “paintbrushes,” which “ran” to depict the mountain. These images rendered Potosí as an old man (viejo) “with gray hair and a long beard.”Footnote 49 He was dressed in clothes of silver, adorned with an imperial crown encircled with a laurel, and clutched a scepter and bar of silver. Underneath him were hunks of precious metal, bars, and coins, which represented the process by which human activity transforms silver from ore to currency. The plants scattered amongst this silver at various stages of processing called to mind period comparisons between agricultural and mineral wealth, both of which were thought to originate from nature for human use. Arzáns’s treatment of Potosí reveals the way he and other individuals of European descent employed corporeal metaphors to conceptualize nature’s mineral riches and their relationship to the corporate body of human society.

Arzáns described Potosí using language and terminology drawn from early modern treatises on governance. The mountain itself is described as a male ruler of nature’s materiality: it was the “emperor of mountains,” “king of hills,” and “prince of minerals.”Footnote 50 In contrast, the town itself was rendered as a female ruler, noblewoman, and mother of nature’s materiality and European and Indigenous populations. Potosí’s hill was described as an “empress of the towns and places of the New World,” “queen of her powerful province,” “princess of the Indigenous populations,” a “benevolent and pious mother to indifferent sons,” and a “lady of treasures and fortunes.”

While these descriptors emphasize the mountain’s agency and power, elsewhere Arzáns depicted Potosi as a corporeal body that served, influenced, and in turn was shaped and violated by human activity. Arzáns narrates that Potosí was a “body of earth” with a “soul of silver.” The silver mountain, in his view, has mouths, eyes, and a heart, which exist for the benefit of humans. The mountain’s more than 1,500 mouths “call humans” in order to give them its treasures; its eyes exist “in order to see their necessities.” Its generosity leads it to give them its heart.Footnote 51

Just as the mountain ruled over other natural bodies, Arzáns depicted Potosí as a ruler of men. According to him, the mountain served as a lord, ruling over five thousand Indigenous Andeans, who “remove[d] its entrails.”Footnote 52 This metaphor calls to mind early modern European conceptions of the body politic in organic, embodied terms, with rulers as the heads and other members contributing to the well-being of society as feet, hands, legs, and so forth.Footnote 53 Here the mountain itself is a “lord” over these individuals, but they do not inhabit the same body.Footnote 54 Rather, those who serve the lord simultaneously consume or destroy it by removing its entrails. This depiction resonates with and extends early modern conceptions of the relationship between rulers and the common good. Early modern authors drew on the examples of Aristotle, Cicero, and later writers, who explained the existence of political communities by the actions of “great and wise” men who convinced others, who previously “wandered in fields in the manner of beasts,” to act not for individual greed and ambition (cupiditas) but for the common interest (communis commodi causa).Footnote 55

Writers of early modern treatises on governance and mirror of princes manuals illustrated this quality for their readers by drawing on the examples of great men from antiquity who sacrificed their fortunes and family in the service of the republic. In his 1597 Politica para corregidores (Art of governing for provincial governors), for example, Jerónimo Castillo de Bobadilla (1547–1605), then serving as a counselor to Philip II (1527–98), described how the ancient Romans had chosen for their leaders individuals who died in such states of poverty that they were unable to allow their daughters to get married.”Footnote 56 The mountain of Potosí, according to Arzáns, follows in their example, for it allows those it serves to remove its very entrails for their own consumption.

The relationship between Potosí, human individuals, and corporate society is predicated on construction and destruction. Arzáns describes Potosí as a “trumpet that sounds over the earth,” a “paid army against enemies of the faith,” and a “city wall,” “castle,” and “formidable work” that impedes such enemies.Footnote 57 The mountain is thus an entity that is constructed and acts for the benefit of those of the Catholic faith. On the other hand, Potosí’s treasures are only able to be accessed through human-led disturbance of the natural environment. Humans “cut the wind,” “plough through the sea,” and “disturb the earth.”Footnote 58

The image of a mountain as a violated body was a recurring motif in European descriptions of Old and New World mining. Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert has shown how elites in New Spain drew on images of the body to discuss issues of labor and administration in relation to colonial silver mining.Footnote 59 In the passage with which this introduction opens, Borja y Aragón similarly underscored his argument regarding the correct course of action to ventilate Huancavelica by describing the mountain as a mutilated body sustained only by the same human interventions that had harmed her. His depiction resonates with a scene employed by Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes to reflect on gold panning in La Española. In his 1535 Historia general de las Indias, Oviedo warned that improper valuation and use of the divine gift of precious metals results in the “earth, our universal mother,” being “broken and opened in many parts,” as men set themselves to “strike veins of gold in her entrails and inner parts.”Footnote 60

Perhaps one of the most vivid European examples of nature portrayed as a wounded maternal body is the late fifteenth-century dialogue Iudicium Iovis (Jupiter’s judgment), composed around 1490 by the Bohemian humanist Paulus Niavis (1460–1517).Footnote 61 This mythological court case depicts Mother Earth—represented as a chaste woman with a pale face, streaming tears, torn garments, and a punctured body—suing a miner before Jupiter. Her advocate Mercury accuses the miner of matricide, describing how he “penetrates into the entrails of his mother,” “ransacks her womb,” and injures “all the inner parts.”Footnote 62 Mother Earth appears “full of wounds” and “splattered with blood,” her “whole body covered with cruore” and devoid of “grace and beauty.”Footnote 63 The miner defends himself by referencing Pliny, arguing that Earth was created solely for human use.Footnote 64 Jupiter ultimately defers judgment to Fortuna, who rules that while humans must “ransack mountains” and “offend nature,” their bodies will also be “devoured by the Earth” and “suffocated by poisonous airs.”Footnote 65 This reciprocal relationship positions neither as dominant, but, rather, depicts humans and nature as bound in cycles of mutual dependence and vulnerability.

This complex understanding of human-nature interwovenness depicted in Niavis’s dialogue reflects a broader early modern cosmological framework in which material bodies were not only embedded within but also permeated and animated by a unified system of correspondences. Nature’s materiality was understood not only in relation to the body politic but also in relation to larger cosmic forces. Early modern Europeans tended to conceptualize this relationship through Aristotelian matter theory, which imagined the terrestrial sphere composed of four elements and influenced by the celestial region. This conceptualization was still very prominent in the eighteenth century, as is evident in the iconography developed for the 1719 feast celebrating the marriage of Maria Josepha (1699–1757), daughter of Emperor Joseph I (1678–1711), and Saxon elector prince Friedrich August II (1696–1763), son of Augustus II the Strong (1670–1733). This feast, which was held in Dresden, took as its motto Constellatio Felix (a promising or successful constellation) and was thematically staged as a festival of the seven planets.

The final act and climax of the celebration was held at the site known as Plauenscher Grund and centered on the planet Saturn. Footnote 66 Numerous surviving artifacts and visual representations reveal an elaborate iconography that highlighted the mutual permeation of earth’s materiality, the body politic, and the cosmos.Footnote 67 Large silver medals (fig. 1) minted to commemorate the occasion employ rich symbolism that provides insight into the way nature’s materiality was conceptualized in relation to the influences of the seven planets on the earthly sphere. These medals were crafted not only in silver but also in gold and bronze. The obverse depicts the patron of mining, Saturn, seated on a boulder, holding a scythe in his left hand while inscribing a plaque: “Memoriæ Saturnalia Saxoniæ MXXIX” (Memories of the Saxon Saturnalia 1719). On the reverse, the medal features a cosmological depiction that directly corresponds with the illumination displayed on a rock cliff at the festival site as described in the anonymous festival book.Footnote 68

Figure 1. Heinrich Paul Groskurt. Silver medal on the occasion of the marriage of Electoral Prince Friedrich August (later Friedrich August II or August III of Poland) to Archduchess Maria Josepha of Austria, 1719. Silver; 55.35 mm; 58.14 g. Coin Cabinet, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, inv. 1989/197.

At the center of the medal the crowned monogram of Augustus II the Strong “AR,” meaning Augustus Rex, is prominently displayed, enveloped by sun rays. Surrounding it were planetary gods with their corresponding symbols, each also representing a metal: above the royal crown, the sun god Apollo/Phoebus, symbolizing gold, whose iconographic representation is reminiscent of Christ’s resurrection. Other deities appeared resting or balancing on clouds: to Phoebus’s right was Luna, symbolizing silver; to the left was Venus, symbolizing copper; below were Jupiter with tin and Mars with iron; and at the bottom was Mercurius with mercury and Saturn with lead. The representation of the Constellatio Felix symbolically proclaimed the dawn of a new golden age under Augustus II the Strong, anchored in the mineral resources of Saxony. The medal intertwines hopes for economic prosperity, sovereign power, and metaphysical divine influences. It ostentatiously displays the mineral wealth of the Kingdom of Saxony, incorporating a metaphysical layer of interpretation that forms an integral part of the rulership over resource landscapes.

Cosmic interpretations of nature’s materiality were not restricted to silver, gold, and precious alloys. A tobacco box from the possession of Augustus II the Strong offers a striking example of how rulership over land and nature’s materiality was represented not only in a cosmological but also in a colonial framework (fig. 2). The front and back of the tin are adorned with a hemisphere surrounded by diamonds and gold stars, with signs of the zodiac made of Saxon carnelian stone. Inside, painted in color under the lid, there is found again the motif of the Constellatio Felix on a small ivory plate. By combining Saxon carnelian, silver, and gold with non-European materials, namely diamonds, ivory, and tobacco, this box serves as a material representation of Saxony’s claim to authority over distant lands and their natural riches.

Figure 2. Tobacco box with hemisphere, ca. 1719–33. Jeweler: Johann Melchior Dinglinger; stonecutter: Johann Christoph. Cut carnelian, carnelian rosettes, diamond, gold, silver, miniature painting in oil on ivory; 1.1 x 7.6 cm. Green Vault, Staatliche Kunstsammlung Dresden, VIII 238. Photo: Jürgen Karpinski.

Corporeal metaphors undergirded many early modern conceptualizations of nature, from cosmic entities to depictions of human communities and their individual members. Such a conception is evident in mining calendars printed in Central European mining regions. Between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, the widespread genre of astrological literature, encompassing affordable prints like writing calendars, almanacs, prognostics (prognostica astrologica), and practical guides (practica), also saw the development of tailored calendars designed for specific professions.Footnote 69 Among these inexpensive ephemeral prints, mining calendars with lengths of up to fifty pages were particularly noteworthy. Designed to address the distinct calendric, astronomical, medical, and economic needs of communities in mining regions, these prints were instrumental in helping individuals navigate the substantial financial stakes and significant physical risks inherent in mining operations. These mining calendars, furthermore, reveal that the interwovenness of nature’s materiality, cosmic forces, and individual and social bodies explored in the previous examples were not restricted to elite actors but resonated more broadly with individuals of different social classes, professions, and educational levels.

These publications advised miners and investors on a range of financial and logistical issues in ways that underscore the intimate connections between human bodies and nature’s materiality. Calendars informed miners and investors which metals were to be mined on a certain day or in certain periods of time. In mining jargon, the German verb for to mine is bauen, which literally means to build. However, in mining jargon bauen meant both mining from a technical point of view and investing in mining in the form of Kuxen. In his Bergk-Practica oder Prognosticon des Bergkwerck bawens, printed in Nuremberg in 1597, the pastor and calendar maker Georg Kreslin (ca. 1563–1628) informs his readers which metals and metal compounds “have a good and happy supply” in the quarters and “bring their blessings abundantly,”Footnote 70 and which—like gold and silver in the Luciae quarter—“have no supply or continuation” and “bear the costs with difficulty.”Footnote 71 Kreslin organized his astrological forecasts according to the four mining quarters—Luciae, Reminiscere, Trinitatis, and Cruci—and not according to months or seasons. This underlines the proximity of the Bergk-Praktica to the Kux trade, or, more broadly, the connections between astrology and market knowledge. Based on these accounts, the trades received their yield (distribution of profits from profitable mines) and also had to pay their subsidy (quarterly payment to the person who maintained the mine). In addition to mining-specific information, these calendars also contained meteorological information, dates of local markets, and information on the mining administration. They also contained advice on when to chop wood, sow seeds, and cut hair, as well as suggesting the best dates for bloodletting. Consequently, this economic information was intimately connected to bodies and their surroundings, articulating both the physicality and moral implications of a mining landscape and its relationship to the human body.

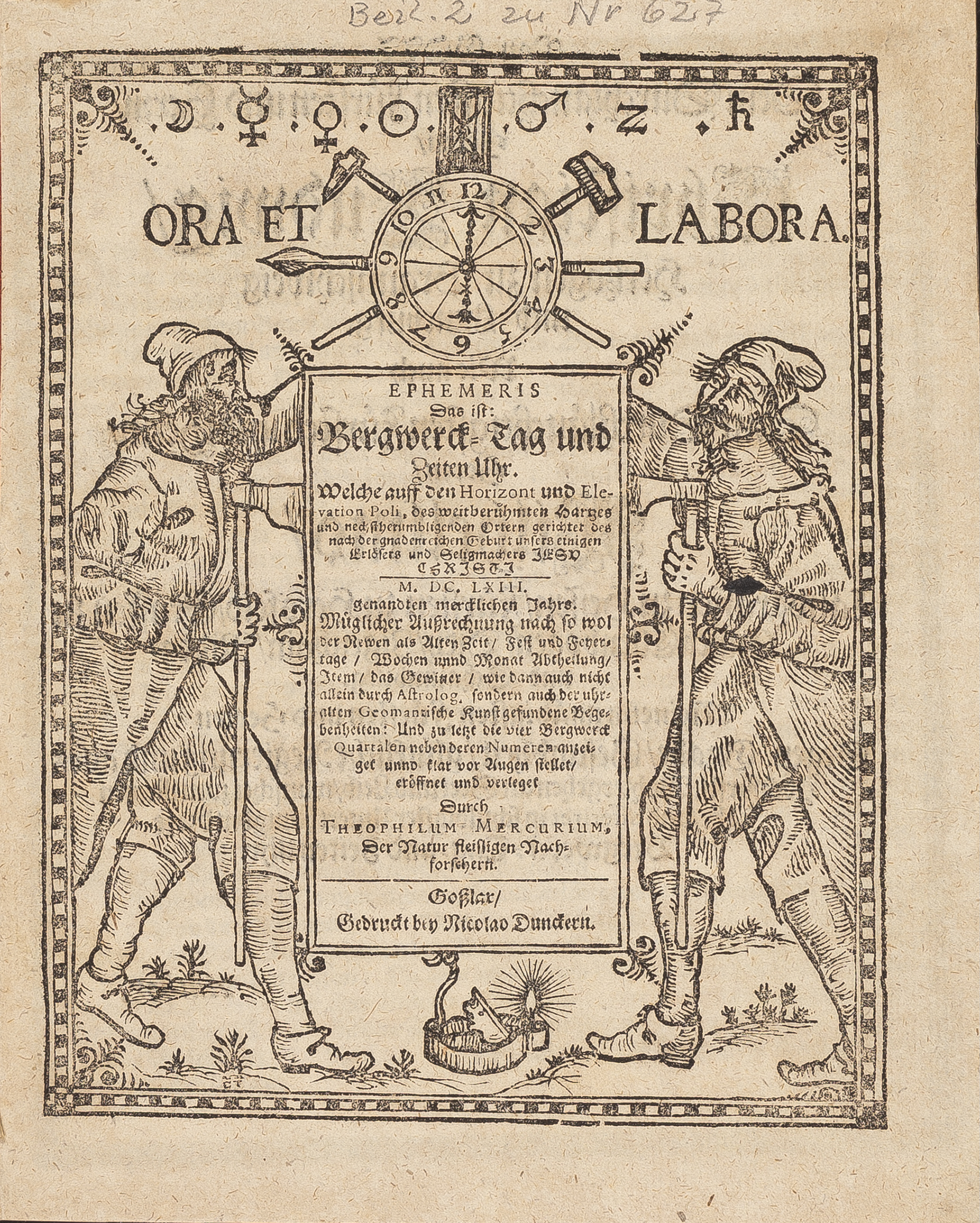

Other authors conceptualized the intra-relation between human bodies and nature’s materiality through the familiar analogy of the microcosm and macrocosm. One example is a set of mining calendars published between 1663 and 1670 by Matthias Ramelow (fl. ca. 1660–70), a physician from Goslar, who wrote under the pseudonym Theophilus Mercurius.Footnote 72 His prints contained astrological calculations on when time is right for prosperous mining but also when miners must be cautious to enter the mines because of toxic vapors. Each calendar contained information on diseases, wars, and the fertility of the soil. Mercurius’s calendars demonstrate how the microcosm-macrocosm relationships, framed by the four elements—air, water, fire, earth—were supported by Hippocratic and Galenic views of the humoral body, as articulated by the author:

The human being, who is a compendium of the great world, and therefore called Microcosmus the small world, comprehends all such three regna within himself, and possesses as well the mineralia as also the vegetabile and animale.Footnote 73

For humoralists, the four properties of heat, cold, moisture and dryness permeated all of creation, tying human bodies and temperaments to planetary influence, seasons, winds, soils, plants, animals, and times of life. Their ameliorating or corrupting effects on humans were at once both moral and physical.Footnote 74

This elemental and humoral conception of the environment links the landscape to the body as both are transforming and being actively transformed through micro/macrocosmic influences. Such cosmic conceptions of the human body can be traced to multiple strands of ancient Greek philosophy, including Stoicism and Neoplatonism, and these conceptions shaped the writings of early modern thinkers such as Henricus C. Agrippa von Nettesheim (1486–1535), Paracelsus (1493–1541), Robert Fludd (1574–1637), and Athanasius Kircher (1602–80). While microcosm-macrocosm relationships have often been studied in relation to Neoplatonism and the alchemical tradition, these mining calendars reveal how they also shaped early modern Europeans’ conceptions of mineral riches.Footnote 75 In Mercurius’s calendars, both landscapes and bodies are visible and tangible expressions of the relationships and actions that shape them. The illustrated title page of his first calendar, of 1665 (fig. 3), vividly demonstrates the intricate connection between the earthly and the cosmological realms. Depicted at the top of the illustration are the seven planetary signs, directly aligning with the fundamental miner’s creed located just below: “ORA ET LABORA” (pray and work). This visual arrangement underscores the belief that celestial influences directly impact and guide the earthly endeavors of mining, intertwining spiritual devotion with daily labor.

Figure 3. Theophilus Mercurius. Ephemeris, Das ist: Bergwerck- Tag und Zeiten Uhr, title page of first edition, Goßlar, 1662. Herzog August Library Wolfenbüttel, sign. BA II 7, Nr. 627, Beilage 2.

THE MINE AS A COLONIAL RESOURCE LANDSCAPE

The previous case studies offer a window into early modern European conceptions of mineral resources as entangled in spiritual and cosmic understandings of the universe and engaged in mutually constitutive relationships with individual and corporate human bodies. A similar vision of mineral resources is depicted in a painting housed today at the Museo de la Moneda (fig. 4) in Potosí and known as the Virgen del Cerro.Footnote 76 Scholars speculate that though it was painted by an unknown artist, the painting may have been inspired by a drawing of the Virgin of Copacabana by the Indigenous artist Francisco Tito Yupanqui (1550–1616) that depicted the Virgin over the mountain of Potosí.Footnote 77

Figure 4. La Virgen del Cerro, ca. 1720. Oil on canvas, 137 x 105 cm. Museo de la Casa de Moneda, Potosí.

The Virgen del Cerro is one instance of many early modern representations of the silver mountain, some of which circulated broadly across Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and China. Footnote 78 While the majority of these depictions represent Potosí as a self-contained mountain, in the Virgen del Cerro, the head and hands of the Virgin Mary are represented as emerging from the mountain, which juts into the heavenly sphere, where God the Father and his son Jesus place a crown on her head. Figures representing the Pope, the Spanish monarch, a member of the Order of Santiago, the viceroy, and another colonial official are situated at the base of the mountain. Behind them, on the surface of the mountain, are individuals of European and Indigenous Andean descent as well as local flora and fauna.

The Virgen del Cerro image has often been interpreted, through a religious or political framework, as shaped by and revealing of both European and Indigenous conceptions of nature’s materiality. One strand of analysis has focused on the way the image incorporates elements drawn from European Christian and Indigenous Andean spiritual beliefs. In this guise, the Virgen del Cerro has been read as evidence of religious syncretism, as part of European missionary efforts, or as an expression of Indigenous resistance. A second strand has focused on the smaller figures on the surface of the mountain, which are thought to reference the legend of Potosí’s discovery. As related in Spanish-language sources, Potosí’s silver deposits came to the attention of the Spaniard Juan de Villarroel via an Indigenous Andean in his service named Huallpa. Huallpa discovered the mountain’s silver when he lit a fire at night and found that melted silver dripped from the roots of the plants he burned. The representation of this legend has led to an interpretation of this image along political lines: there is significant evidence of exploitation of Potosí and other silver deposits before the Spanish conquest, but the myth of untouched silver deposits was part of a narrative that justified the Spanish as divinely ordained exploiters of the region’s silver.Footnote 79

The image, however, can also be read as a window into the resource landscapes of the Spanish colonial Andes. The figures working on Potosí’s surface narrate the Spanish legend of Potosí’s discovery, yet they also represent the mountain as a site of human artifice. The human figures depicted on the surface are engaged in a variety of activities, including prayer, digging into the earth, and lighting fires, which may reference Huallpa’s discovery of Potosí’s silver or the use of fire in the process of refining. This depiction of Indigenous mining labor on the body of the Virgin may also reflect the visual rhetoric of “spiritual mining” that Annick Benavides has noted in seventeenth-century art produced in Peru. According to Benavides, images of the Virgin of Copacabana and other scenes depicting mining represented Spain’s acquisition of Peruvian mineral riches and God’s acquisition of Indigenous souls as joint projects facilitated by Spanish colonization.Footnote 80

Silver’s significance is also evident in the decision to include three representations of silver/lunar disks in a vertical axis in the center of the image. The large silver disk at the bottom calls to mind both the lunar surface and a minted coin; its placement at the bottom of the mountain alludes to the ores underneath Potosí’s surface. Silver circles are also visible as halos atop the Virgin and the dove, who represents the Holy Spirit. Scholars of the colonial Andes have argued that this set of images underscores connections between silver, the moon as a generative force, and the Andean deity of the Pachamama, or Mother Earth, who is evoked by the representation of the Virgin Mary.Footnote 81

These associations would also have resonances for viewers of European descent, who would have been familiar with an iconographic tradition linking the Immaculate Virgin with the moon. They would also have been familiar with depictions of the earth as a nurturing maternal figure, a motif prevalent in the Neoplatonic, Aristotelian, and alchemical traditions, as well as in early modern literary and artistic productions that drew on ancient Greek and Roman representations.Footnote 82 In European visual culture, there has been a significant iconographic association between mountains and the female body, exemplified by sacred figures such as Mary and other saints. The painting Metercia, created in 1513 by the artist known as “L.A.” and located in the Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Rožňava, Slovakia, illustrates a profound connection between fertility and divine creation (fig. 5). It merges the figures of Anna Selbdritt and the Trinity, depicting the earth’s bounty as akin to the fruits of the maternal womb. This painting links the fertile bodies of female saints to the Immaculate Conception and Incarnation, reflecting the divine processes of metal emergence and refinement.Footnote 83 This artistic tradition resonates deeply with the imagery of Virgen del Cerro, weaving together themes of fertility, sacred femininity, and the generative powers of the natural world.

Figure 5. L.A. Metercia (St. Anne, the Virgin Mary, and the Baby Jesus in a Mining Scene), 1513. Oil on canvas, 170 × 125 cm. Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Katedrála Nanebovzatia Panny Márie), Rožňava, Slovakia. Institute for Material Culture, University of Salzburg. Photo: Peter Böttcher.

Period writers (and modern scholars) often describe Potosí as a locale hostile to human and natural life. Its cold temperature and altitude allegedly made it a place devoid of human, plant, and animal life.Footnote 84 The Virgen del Cerro counters this view by depicting Potosí as a site of nature’s bounty, celebrating the variety of plant and animal life found in the Andes; various types and sizes of trees and flowers, which themselves symbolize fertility and whose growth depends on the cycles of the sun and moon. A variety of wild animals native to the region, including llamas, lions, and vicunas are rendered in detail; these testify to Andean conceptions of the mountain as a generative force: Incan origin myths describe llamas as emerging from the lakes and summits of mountains. The aquatic birds and vizcacha, a native rodent that resembles a rabbit, were able to cross natural boundaries, moving between the sky, land, water, and underground; their presence reinforces the connections made by the multiple renditions of silver regarding the interdependence and relationship between the heavens, and the terrestrial and underground realms.Footnote 85

The image links these three realms in ways that resonate with European and Indigenous Andean conceptions of the spiritual and natural world. The sun and moon, depicted in traditional European iconography on the two sides of the mountain, were worshiped by the Incas as divine beings who were brother and sister, as well as husband and wife, a familial relationship that was instantiated by Incan rulers who also married their sisters. Both were seen as vital for agriculture and thus for fertility. Metals were significant for the Incans not for monetary exchange but for their religious significance: gold was associated with the sun and silver with the moon. As Sabine MacCormack describes, Andean peoples saw the natural world—the plains, mountains, sky, and waters—as the “theatre and dramatis personae of divine action.”Footnote 86 Spiritual significance was afforded to celestial bodies, including the sun, moon, and stars, as well as to stones, rivers, and mountains, deemed holy places or huacas. These natural entities were understood to be places where divine presences representing the history and concerns of the community resided, promoting an intimacy between humans and the natural environment understood in spiritual terms.Footnote 87 The mineral kingdom was conceptualized in intimate connection with the vegetable and animal kingdoms, collectively viewed as manifestations of divine creation and governed by divine providence.

Scholars have argued that such conceptions of nature’s materiality were characteristic of Indigenous communities throughout the Americas. For Taíno and Mesoamerican communities, subterranean spaces served as bridges in a concentric model of the universe consisting of the heavens, the visible world we experience, and a water realm below. Linguistic analysis of Cristóbal Colón’s (1451–1506) diary reveals that the Taíno peoples of the Antillean islands in the Caribbean conceptualized their practices of extracting gold as a communal activity linked to lunar cycles that had spiritual significance related to creation and fertility.Footnote 88 Taínos traced the origins of their people, culture, and time itself “to the emergence of stunning golden objects, metal-like feathers, and fragrant, yellow plants.”Footnote 89 This depiction of the Taínos is just one example of the more general consensus that Indigenous Americans understood metals as linked to human activity, endowed with generative properties, and reflective of and embedded in the spiritual forces that animated the wider universe. Such a characterization has often been framed in opposition to the capitalistic and extractivist approach associated with and typically attributed to early modern Europeans.Footnote 90

Employing the resource landscape framework more broadly could complicate this antagonistic depiction. As the other examples in this introduction and the special issue reveal, early modern actors inside and outside Europe tended to view the natural world in spiritual, reciprocal, and relational ways that perhaps more closely resemble the views ascribed to non-European early modern actors than is often acknowledged. It may be that one reason why European actors were often able to render and incorporate non-European, Indigenous conceptions of the natural world in ways that modern scholars have been able to recover was due to the resonances rather than the dissonances between the two. Rather than approaching European and non-European resource landscapes as inherently oppositional, it may be helpful to look at more particular, localized areas of difference. Allison Bigelow, for example, offers a useful model of such an approach. While acknowledging the broader similarities in the ways that Taíno origin stories and early modern European philosophical and alchemical theories linked plants and minerals, she notes that Aristotelian matter theory led Europeans to see the boundaries between the two as more rigid.Footnote 91

EARLY MODERN RESOURCE LANDSCAPES

The case studies that comprise this special issue provide a window into early modern resource landscapes writ large that underscores and amplifies the preceding analysis focused on mining and metals. They reveal the way that early modern historical actors across time and geographic region similarly conceptualized nature’s materiality in relation to their spiritual beliefs, understandings of the larger cosmos, and individual and social bodies. While these case studies emphasize the perspective of early modern European actors, we believe that the heuristic of resource landscapes could be fruitfully applied to other geographical regions.Footnote 92 Consideration of additional cases from a broader geographic and temporal scope would no doubt amplify and add nuance to this picture.

Several case studies underscore the way nature’s materiality was conceptualized in relation to religious belief. Melissa Reynolds, for example, reads the English physician Timothy Bright’s The sufficiencie of English medicines (1580) as an expression of the way nature’s materiality was entangled with notions of divine providence, medicine, and visions of empire. She explores Bright’s resistance to incorporating New World materia medica, exemplified in Nicolás Monardes’s Historia medicinal (1565–74), which appeared in English translation the same year as Bright’s The sufficiencie of English medicines. While previous scholars have framed such resistance in relation to period debates about the merits of the local versus the exotic or ancient precedent versus novelty, Reynolds highlights the way Bright’s and Monardes’s responses to New World flora were shaped by their differing conceptions of God’s role in the creation and apportionment of nature’s materiality. Whereas Monardes’s understanding of providence was universalist, Bright took a stance that Reynolds describes as “anti-imperial,” namely that “differing and unequal apportionment of medical resources across the known world reflected God’s differing … provision for differing … peoples.” For Bright, the “global resource landscape” was a “marker of difference,” which resided in the soul, was manifest in the body, and was made visible through medical experimentation.

Divine providence is also highlighted in Danielle Clarke’s analysis of the poetry of Lady Anne Southwell (1574–1636). Southwell employed scriptural models about good agrarian practice to address nature’s materiality and human conduct. Her poetry exemplifies the way colonial approaches to natural resources were legitimized through scriptural precedents, with agricultural metaphors serving dual purposes of religious conversion and landscape transformation. Particularly significant is Clarke’s examination of how notions of improvement connected spiritual salvation with resource management, creating a moral imperative for colonial intervention. By centering her analysis on Southwell’s consideration of nature’s materiality, Clarke explores the methodological implications of approaching early modern sources using modern environmental thinking. She extends this analysis to highlight the paradoxical role that women occupied in early modern settler colonialism. Though women were central to the enterprise, they were not given agency in terms of land ownership and legal processes.

Gabriele Marcon highlights the way spiritual understandings of nature’s materiality were entangled with laboring human bodies. His analysis centers on a sixteenth-century chronicle, penned by a local clerk from Tretto (Veneto) named Iseppo Gorlin, that narrates the discovery of silver ores by the German friar and magus Fra Bernat. Gorlin’s text, according to Marcon, reveals that early modern actors conceptualized mineral riches in terms of agriculture and simultaneously relied on spiritual and magical understandings of the world to contend with the uncertainties inherent in mining operations.

The relationship between the body politic, governance, and nature’s materiality is explored in contributions by Lavinia Maddaluno, Caroline Elizabeth Murphy, and William Rhodes. Maddaluno draws on a variety of sources, including administrative records, archival documents, period legislation, and agricultural and medical treatises, to examine socioeconomic, cultural, scientific, and medical responses to rice cultivation in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Milan. Today we might be tempted to view rice cultivation in terms of the modern analytical category of subsistence; Maddaluno demonstrates that rice was viewed by period actors in more expansive terms—indeed, as a potential disruption to the natural, theological, and social order.

Maddaluno’s analysis of the Duchy of Milan can be set in dialogue with Murphy’s reinterpretation of the Jesuit Giovanni Botero’s writings on statecraft. As Murphy emphasizes, early modern Italian interest in aquatic landscapes reflected the response of centralizing Italian city-states to the cooler, wetter climate of the Little Ice Age. In her contribution, Murphy builds on previous scholarship that has highlighted Botero’s focus on industry as a key component of political knowledge. She argues that industry, for Botero, included not just human-made environments like factories and workshops but also the natural environment. Aquatic environments, particularly, shaped Botero’s understanding of what comprises and contributes to secular greatness (grandezza). This is evident in the way Botero employs aquatic metaphors to describe political states, draws attention to the role of hydraulic navigation as a means of supporting communities, and urges rulers’ careful management of aquatic environments.

Competing imperial ideologies are at the center of Rhodes’s exploration of the entanglement of nature’s materiality, labor, and violence in Edmund Spenser’s A View of the Present State of Ireland (1596) and Bernardo de Vargas Machuca’s Milicia y descripción de las Indias (1599). Though their texts represent two rival states’ colonial ambitions, Rhodes argues that Spenser and Vargas Machuca arrived at similar understandings of the means and ends of colonial warfare. Both Spencer and Vargas Machuca viewed Ireland and New Granada as threatening locales. Their dangers stemmed both from nature’s materiality and the relationship between this materiality and the Indigenous inhabitants of these areas. Colonial warfare, both argued, was a key means of countering this threat by transforming subsistence activities that had once linked Indigenous peoples to the land into new forms of labor that generated colonial wealth.

Mackenzie Cooley also draws attention to the agency of nonhuman actors in the context of European colonization. Her contribution centers on a textual source often seen as emblematic of early modern Spanish colonization: specifically, she considers the responses to the questionnaires developed by the first cosmographer-chronicler of the Indies, Juan López de Velasco (1530–98), a text now known as the Relaciones geográficas de Indias.Footnote 93 By applying the tools of the digital humanities and the insights of modern climatology to this text, Cooley proposes a revised understanding of Alfred Crosby’s “Columbian Exchange.”Footnote 94 In place of Crosby’s hypothesis of “sweeping arrows of transformation shaped by imperial logic,” Cooley proposes that period actors’ experiences are better understood through the metaphor of a patchwork quilt. The exchange of flora, fauna, and microorganisms that followed Columbus’s journey to the Americas was characterized by local and regional differences, which were the result of actions that were both intentional as well as makeshift, irregular, and improvised.

Read in dialogue, these contributions offer insight into distinctively premodern conceptions of resources and landscapes. In multiple contributions, landscape appears neither as an inert, natural backdrop nor as a passive site of human exploitation but as an active force whose relationship with human society was dialogic. Rhodes highlights the way that Spenser and Vargas Machuca conceived of Irish and New World nature simultaneously as an impediment to and a facilitator of colonization and productivity. Giovanni Botero, Murphy notes, similarly envisioned water, with its physical properties of strength (forza), firmness (fermezza/sodezza), and viscosity (viscosità), as key to ensuring a state’s productivity and grandezza and as an agent that shaped the people who lived there.

Though the contributors rely on the modern term resource, their analyses underscore the inadequacy of the term for capturing premodern conceptions of nature’s materiality. While Murphy focuses her contribution on Botero’s thoughts regarding “aquatic resources,” she notes that Botero employed the terms richezze (“riches”) or frutti della terra (“fruits of the earth”) to refer to what we today call natural resources. In describing human interactions with nature, Botero relied on terminology that resonated with Aristotelian matter theory. For Botero, human labor was the efficient cause—the active agent of change—that transformed raw natural matter (materia prima) into finished goods (materia lavorata).

Botero’s terminology resonates with those of other period actors, both European and non-European, who conceived of nature’s bounty as “treasures” bestowed by the world’s creator. In the Latin-European and Iberian world, metals, minerals, and previous stones were often described as thesaurus / tesoros, whose acquisition by humans was conceptualized through agricultural metaphors, including gathering and harvesting.Footnote 95 For Vargas Machuca, the project of Spanish colonization was driven by la riqueza (the riches), a term that encompasses nature’s materiality but also the financial investment and physical labor of the soldiers whose efforts facilitated imperial expansion.

Early modern European actors, these contributions make clear, viewed what today we regard as a dialogue between humans and nature as a three-way interaction between humans, nature, and God. Marcon, Clarke, and Reynolds specifically highlight the perceived role of God in apportioning nature’s bounty and making it accessible to humans. Yet, the agency premodern actors assigned to God is visible in the remaining contributions as well. For secular and religious officials in the Duchy of Milan, as Maddaluno illustrates, nature’s materiality—what today we would describe as the natural resource of rice and the wet landscape required for its cultivation—impinged on and influenced human spirituality and morality. Viewed through the lens of Aristotelian conceptions of decline and renewal, rice cultivation was criticized by detractors as introducing unnatural unruliness and, in particular, sin and moral depravity, into nature’s materiality in ways that negatively impacted both the natural course of other crops and human industry. Murphy notes that, according to Botero, the existence of water and its possession of physical properties that facilitated transportation and communication were signs of God’s benevolence and desire to promote commerce and, through it, communication and communion.

CONCLUSION

Current scientific research on the Anthropocene utilizes quantitative data and models to analyze the extent and intensity of human-induced changes in Earth’s history. Plotting changes to these levels over time reveals that the transition from preindustrial to modern levels can be modeled as an exponential function. This approach positions the period traditionally termed early modernity as one of transition marked by fundamental economic and ecological shifts that led to capitalism, growth, and ecological degradation.

Humanities scholars’ contributions to Anthropocene studies have tended to adopt these methods and teleological outlook. Their interdisciplinary approaches position climatological findings as foundational to historical inquiry, leading to systematic reinterpretations of environmental history and resource utilization through contemporary climatological models applied to early modern case studies. The resulting analyses often reconstruct the early modern period in ways that parallel both traditional progress narratives and current Anthropocene discourse—either as the genesis of present environmental crises or as an archive of abandoned sustainable practices that might inform contemporary solutions. This special issue takes as its core assumption that approaching the historical past purely in light of scientific interpretation and data is problematic. Such an approach oversimplifies the complex and multifaceted interactions between human societies and their environments, and fails to account for the varied historical trajectories and outcomes that have shaped environments.

The authors of this special issue approach human activity and socionatural interactions on Earth not simply as the result of measurable factors, but instead as the outcome of a complex array of choices, beliefs, worldviews, hopes, and promises. The goal is not to align historical periods in a seamless linear narrative. Rather, the contributions focus on creating new links between past and present realities in order to enhance the comprehension of both. These studies seek to disrupt a teleological narrative that approaches early modernity in relation to the modern present. In doing so, they embrace a view of early modernity articulated by Adam Bobbette and Amy Donovan in their notion of “amodernity,” a term they developed from Bruno Latour’s theoretical framework. Rather than accepting early modern as a historical periodization on a progressive historical timeline, the amodern perspective fundamentally questions the conceptual division between modern and non-modern. This approach “abandons the idea that there is a non-modern, primitive, or savage state that preceded the modern.”Footnote 96