1 Introduction

In February 2017, the US Central Command tweeted photos of Kurdish female militants fighting against ISIS (the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) with the caption “Ready for the fight” (US Central Command, 2017a). A few minutes later, they followed with another tweet: “By popular demand, more photos of the female fighters of the Syrian anti-ISIS campaign” (US Central Command, 2017b). Notwithstanding the concerns of Turkey, a NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) ally that considers the Kurdish group a terrorist organization and a vital national security threat, the US did not hesitate to demonstrate open support for them. Similarly, the French President and the Swedish Defense Minister officially welcomed Nesrin Abdullah, the commander of the YPJ, an all-women Kurdish fighting unit of the Democratic Union Party of Syria (PYD). Prioritizing anti-ISIS efforts over allied concerns may seem routine within counterterrorism and geopolitical strategy, but this focus would overlook a crucial gendered aspect: how showcasing female fighters can be strategically used to shape international perceptions, gather public support, and legitimize foreign policy moves by appealing to progressive or moral values.

Alongside official channels, Kurdish female fighters also attracted significant popular international attention. Major Western media outlets, including CNN, BBC, The Guardian, PBS, and even teen and fashion magazines like Teen Vogue and Marie-Claire, featured Kurdish female fighters, celebrating their bravery and highlighting the extraordinary nature of women taking up arms (Griffin, Reference Griffin2014). Headlines read “Women, Life, Freedom” (Lazarus, Reference Lazarus2019), “ISIS’s Biggest Fear Is Being Killed by Girls” (Webster, Reference Webster2015), and “A Bullet Almost Killed This Kurdish Sniper. Then She Laughed About It” (Horton, Reference Horton2017).

Examples of women militants attracting international attention are bountiful (Darden, Henshaw, and Szekely, Reference Darden, Henshaw and Szekely2019). Women participate as combatants in over one-third of contemporary armed rebellions, and as noncombatants in two-thirds, impacting conflict dynamics in unique ways (Loken and Matfess, Reference Matfess2024; Wood and Thomas, Reference Wood and Thomas2017). Female insurgents receive more sensationalized media coverage than men, which enhances their propaganda value (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2018) and raises the likelihood of attacks conducted by females, as these actions are expected to gain widespread attention in the Western media (Weeraratne, Reference Weeraratne2023). Indeed, an essential aspect of rebels’ public engagement efforts often involves the intentional inclusion of women insurgents. Many women actively participate in international propaganda activities (Başer, Reference Başer2022) and use media to raise awareness about their cause (Stallman and Hadi, Reference Stallman and Hadi2025). From Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Ethiopia to Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in Peru, and Liberation of Tamil Tigers Eelam (LTTE), numerous rebel organizations promote their female fighters to attract third-party support, sometimes even exaggerating the prevalence of their women militants. For instance, the UN Mission in Nepal reported that Maoists inflated the proportion of women, nearly doubling the actual figure to boost international propaganda (Ortega, Reference Ortega2010: 25). Despite such emphasis on showcasing women by rebel organizations, whether women-focused outreach activities resonate with audiences or translate into tangible support remains unclear.

Rebel groups seek support from foreign patrons to increase their chances of success. Research on external support in civil wars typically focuses on the supply side – the strategic calculus of foreign governments – at the expense of rebels’ agency, and tends to ignore why rebels spend considerable resources on outreach activities instead of concentrating on frontline gains (Huang, Reference Huang2016). Rebels lobby abroad, hire public relations experts, establish international offices, and leverage media platforms to attract support from international actors (Huang, Reference Huang2016).

For example, the Syrian Democratic Council – the political wing of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) – maintains a mission in Washington, DC, and uses gender equality as a key element of its appeal. Its website states:

Studies show that peace agreements are more likely to succeed when women participate, and that greater political and social empowerment of women is essential for combating extremism and building free and fair societies. As the only actor in Syria to prioritize women’s rights and implement pro-women policies on the ground, we believe our laws and policies are a model for the future of the country that the world should support.Footnote 1

This rhetoric mirrors the gender-progressive stance embraced by international communities, especially among democracies, positioning the SDF not just as a military force but as a promoter of democratic and gender-inclusive values. It highlights how rebels fight not only on the battlefield but also in the arena of international legitimacy, presenting themselves as aligned with liberal democratic ideals. The money and effort spent on these outreach activities suggest that these strategies are integral to how conflicts unravel – yet their impact remains understudied.

This Element fills this gap by evaluating how the gendered imagery of rebel organizations influences foreign perceptions and foreign policy decisions to support them. It focuses on foreign public opinion toward female combatants and its impact on foreign governmental support for civil wars.

Understanding whether and how rebels’ gendered outreach strategies affect foreign public opinion and external support matters for several reasons. First, external support is essential for rebel goals such as maintaining territorial control, attaining international recognition, inclusion in peace talks, prolonging conflict, and imposing sanctions on adversaries (Caspersen, Reference Caspersen2009; Regan, Reference Regan2002; Stanton, Reference Stanton2016). To attract support, rebels “market” themselves to transnational patrons (Bob, Reference Bob2005). Understanding how rebels succeed in securing international approval and external support requires examining the factors leading to successful marketing strategies attracting this support.

Second, policymakers, especially in democracies, are responsive to domestic preferences, including foreign policy decisions and the use of force, making them wary of foreign adventurism (Baum and Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2015; Chu and Recchia, Reference Chu and Recchia2022). Supporting a violent group responsible for civilian casualties can serve as fodder for the domestic opposition to undermine government approval and damage the international reputation of a democratic state. Public perceptions are critical here because foreign armed groups lack the legitimacy of an allied state (Kreps and Maxey, Reference Kreps and Maxey2018). Yet, public reaction toward external support for nonstate armed groups has attracted limited attention.

Third, although there is limited empirical evidence on how women involved in conflict are viewed, the political psychology literature widely recognizes that gender stereotypes shape assessments of female politicians. Traditional norms often depict female politicians as ethical, nurturing, and passive (Kahn Reference Kahn1996), whereas male politicians as assertive leaders are better suited for “hard” issues like security or economy (Dolan, Reference Dolan2010). While some recent work demonstrates the persistence of these stereotypes (Aaldering and Van der Pas, Reference Aaldering and Van Der Pas2020; O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2019), disadvantaging women in elections across Western and non-Western contexts (Blackman and Jackson Reference Blackman and Jackson2021; Liu, Reference Liu2018), others find no negative bias toward females in the political sphere (Adams et al., Reference James, Bracken, Gidron, Horne, O’Brien and Senk2023; Schwarz and Coppock, Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022), even suggesting that women can be viewed as more capable than men even in traditionally male domains (Lust and Benstead, Reference Ellen and Benstead2024). This mixed evidence on gender bias in political participation raises questions about whether similar stereotypes might shape attitudes toward female actors in conflict contexts, where perceptions of capability and suitability for “hard” issues like security could be particularly significant. How such gendered understandings impact attitudes in conflict contexts remains understudied.

War is often seen as the continuation of politics by other means (von Clausewitz, Reference von Clausewitz[1832] 1873); however, patriarchal mechanisms dominate war settings much more than they do traditional politics. Men are viewed as natural warriors, whereas women are associated with peace, nonviolence, and passivity. Further, “ambiguity is endemic to civil wars,” and uncertainty about actors’ intentions, aims, and methods is more prevalent in conflict settings than in traditional politics (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2003: 476). The literature on gender stereotypes in traditional politics suggests that people should rely on these stereotypes to make judgments about conflict. Yet, we know little about which stereotypes inform citizens’ attitudes in conflict settings, to what extent, and how. Understanding how people evaluate gender in rebel groups would contribute to the political psychology scholarship by informing us about how people make judgments in low-information and hypermasculine political settings.

Fourth, assessing which gendered beliefs are reproduced in conflict settings is crucial because these beliefs can contribute to the legitimacy of the organizations (Viterna, Reference Viterna, Bosi, Demetriou and Malthaner2014). Gender-diverse cadres can appeal to foreign audiences and be leveraged by the rebels as the embodiment of gender-equal policies to humanize the groups. Building legitimacy is critical for the international approval of rebel groups because rebels who appear legitimate can better attract external support and, thus, favorable conflict outcomes (Jo, Reference Hyeran2015; Stanton, Reference Stanton2020).

This Element fills these theoretical and empirical gaps by dissecting the relationship between gender roles, public opinion, and foreign conflict assistance. Particularly, I answer the following questions: How does women’s visible presence in insurgent groups affect foreign support? Do the rebel groups with women fighters attract more support than those without? If so, through which mechanisms does support operate?

I argue that the presence of women sends signals about the rebel group’s characteristics that are different from those of male rebels because traditional gender stereotypes associate men and women with different traits. The gender of rebel group members functions as a heuristic, informing people about the characteristics of the conflict environment, especially in the absence of further information, where there is uncertainty about rebel characteristics. Through survey experiments in different sociopolitical contexts, I examine whether foreign publics prefer supporting groups with female combatants and assess the mechanisms of this preference. Then, using observational cross-national data, I examine whether foreign public attitudes toward female combatants can translate into actual external government support for gender-diverse armed groups.

Traditional gender stereotypes are especially influential in conflict, with citizens often favoring “strong,” masculine leaders in times of war or security threats (Barnes and O’Brien, Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018; Lawless, Reference Lawless2004), while women are deemed to be nurturing peacemakers or passive victims (Sjoberg and Gentry, Reference Sjoberg and Gentry2007). These stereotypes can fuel competing perceptions of rebel groups with female fighters: foreign audiences may dismiss them as weaker and less capable of military success or, conversely, view them as more moderate and morally righteous. Drawing on literatures on social psychology, foreign policy, conflict, gender politics, public opinion, and media studies, I explore how the presence of female militants in rebel groups shapes foreign public perceptions, and garners favorable perceptions even when those groups employ violent strategies that audiences typically disapprove of. The presence of female combatants acts as a gendered signal, shaping perceptions by evoking entrenched expectations of women as peaceful or morally virtuous. Women’s agency in violence creates a cognitive inconsistency that observers resolve by projecting traits like moderation onto the entire group. Media and rebel outreach amplify these entrenched associations, presenting women as mothers, victims, or brave women’s rights activists. This enhances the group’s appeal to foreign audiences and increases foreign support for their rebel groups.

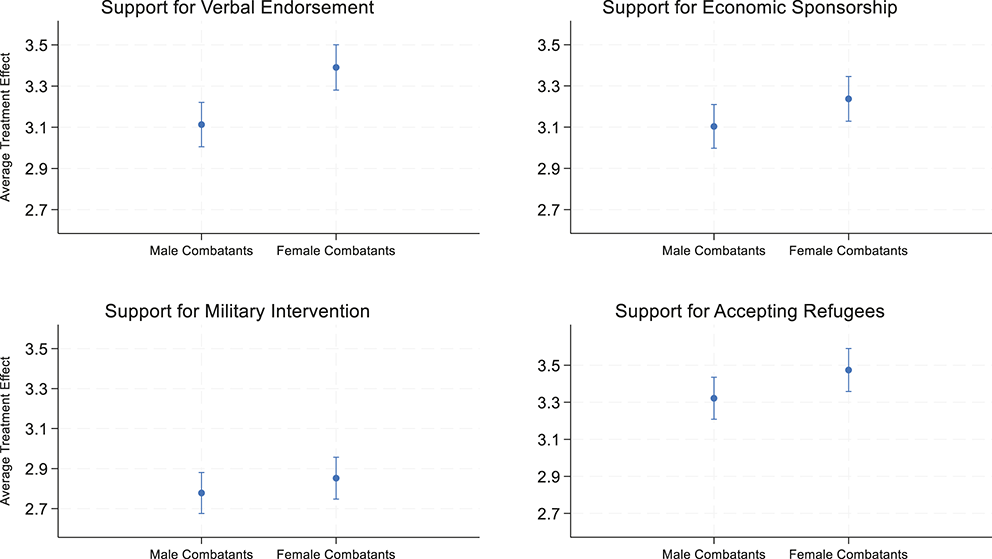

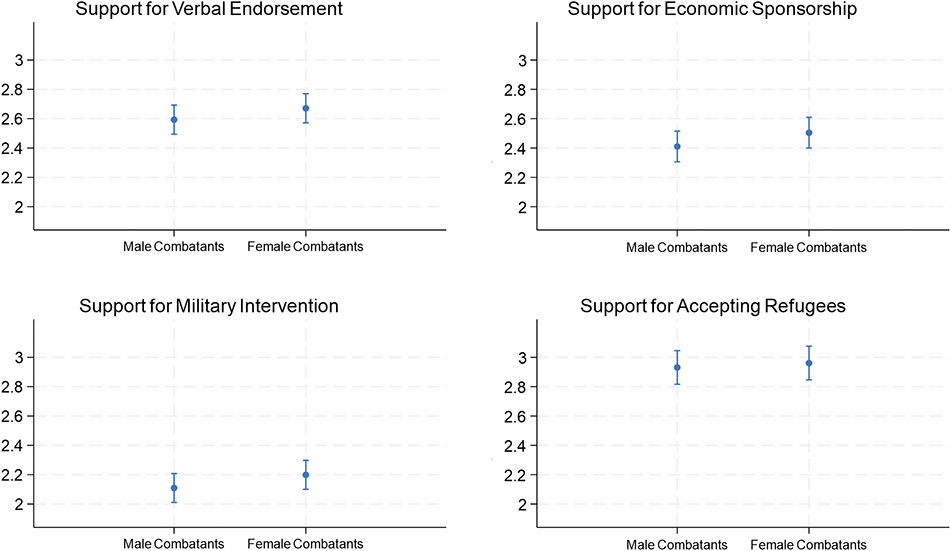

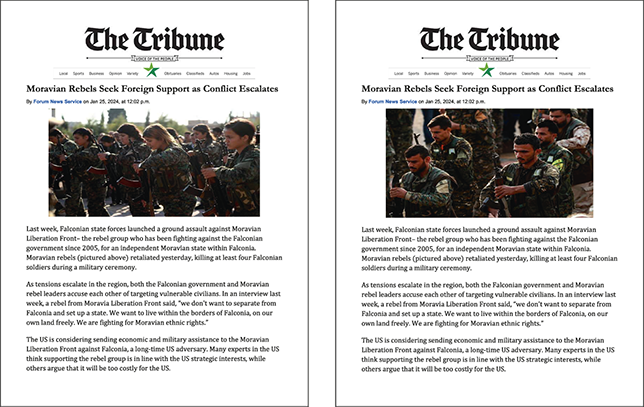

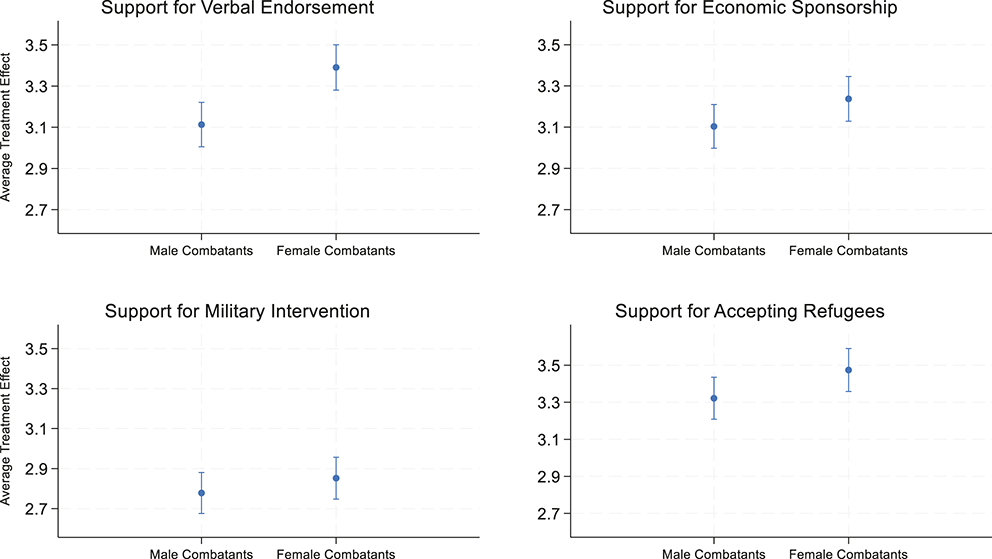

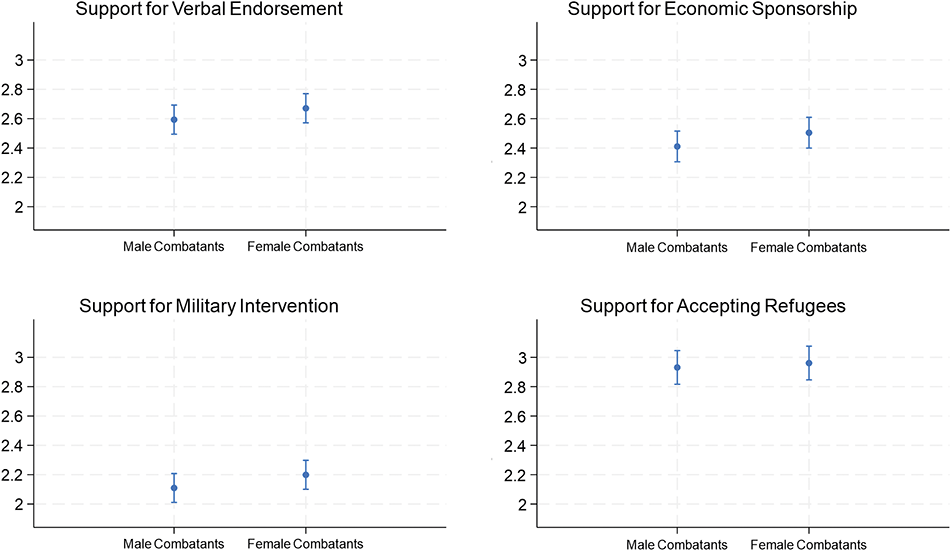

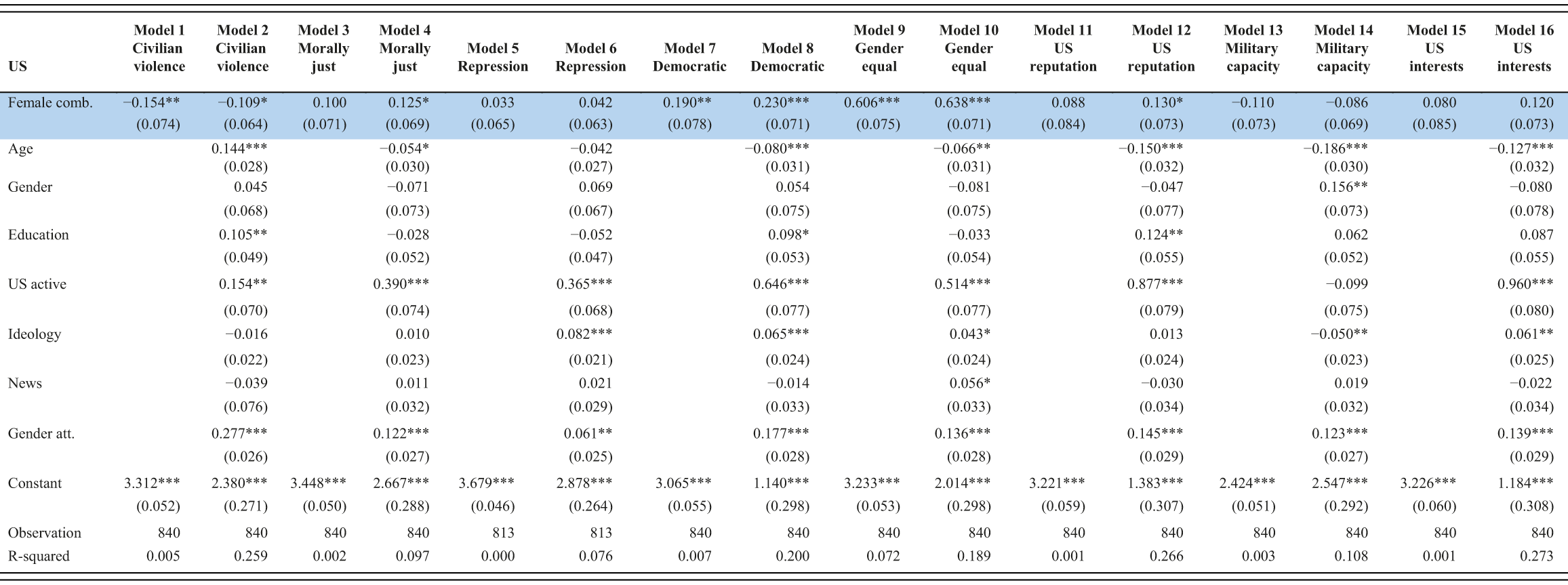

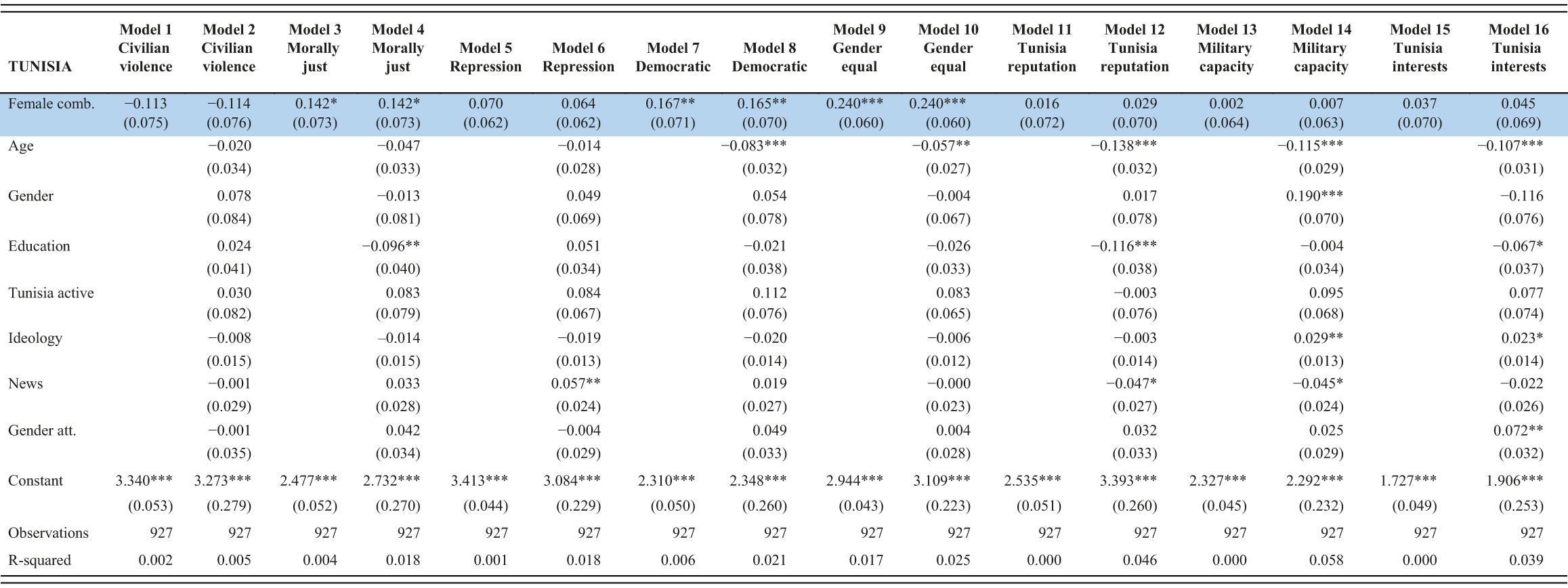

To analyze how conveying the message about the presence of women insurgents attracts support from third parties, first, I conduct original survey experiments in the US and Tunisia to assess micro-foundations of foreign attitudes toward sponsoring gender-diverse armed groups and parse out the mechanisms through which foreign audiences evaluate women’s presence in insurgencies differently from that of male rebels. I examine attitudes toward various forms of foreign support – verbal endorsement, economic aid, military intervention, and refugee acceptance – to pinpoint the extent of female combatants’ impact and to assess whether certain types of assistance are more affected by the gender composition of rebel groups.

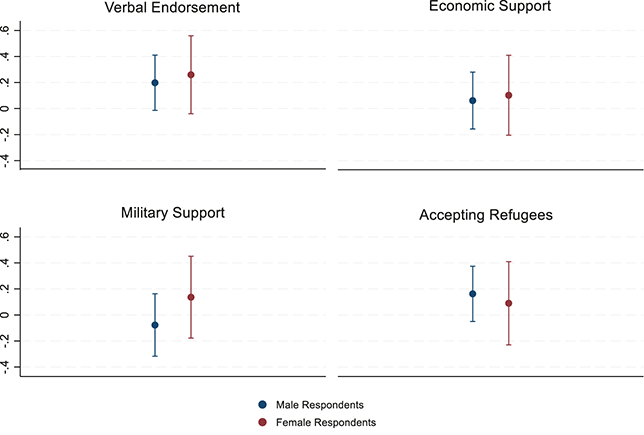

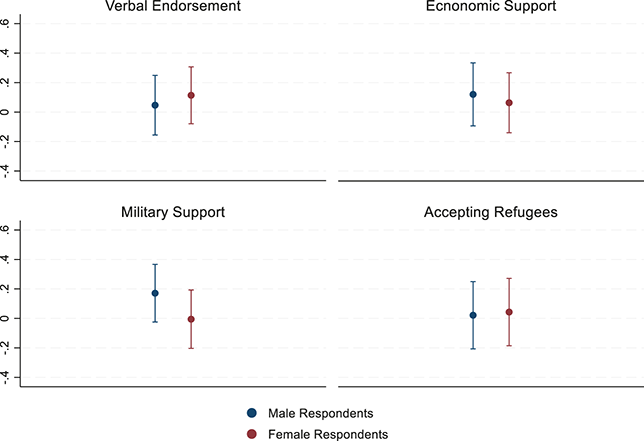

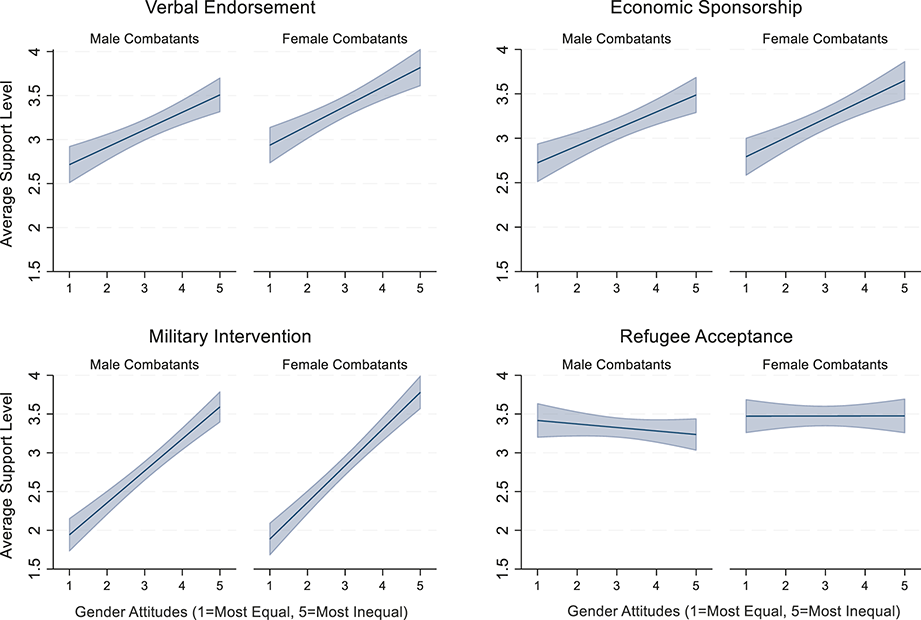

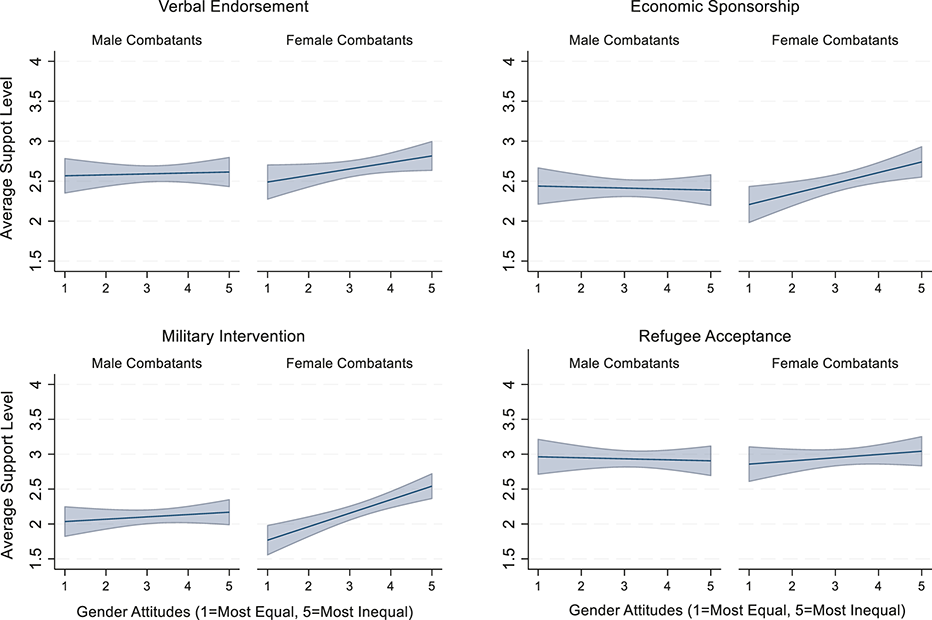

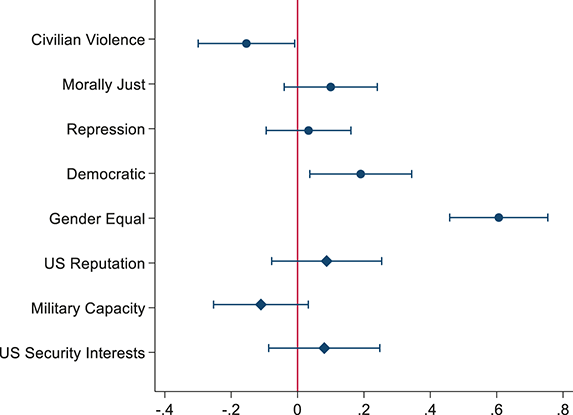

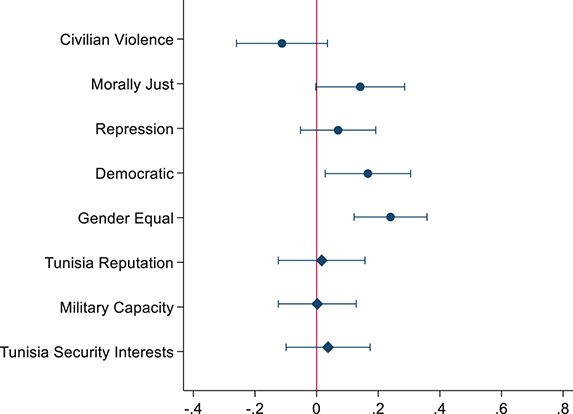

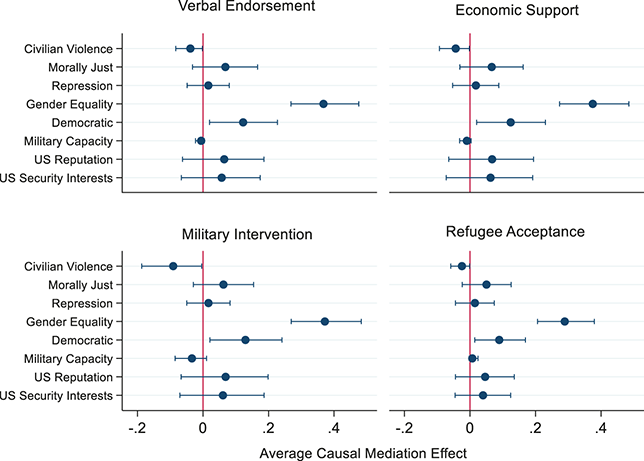

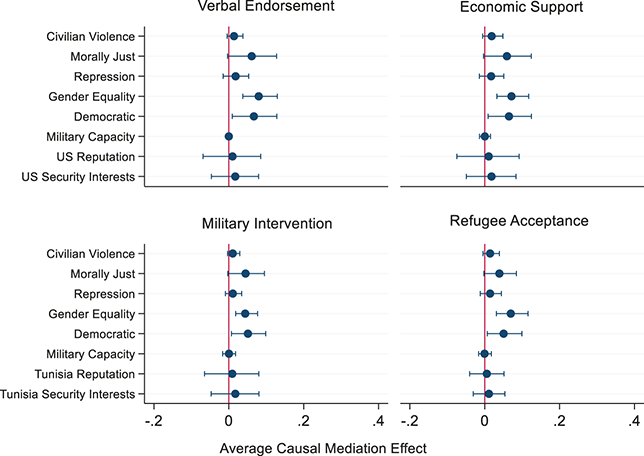

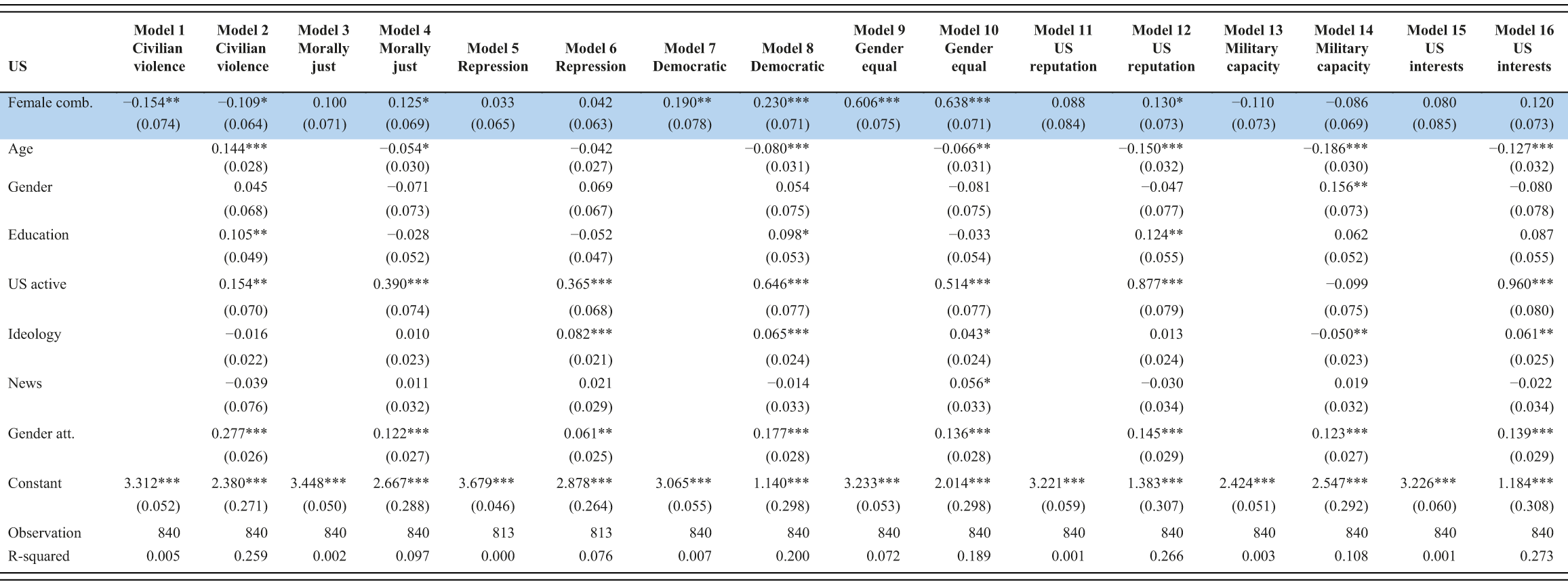

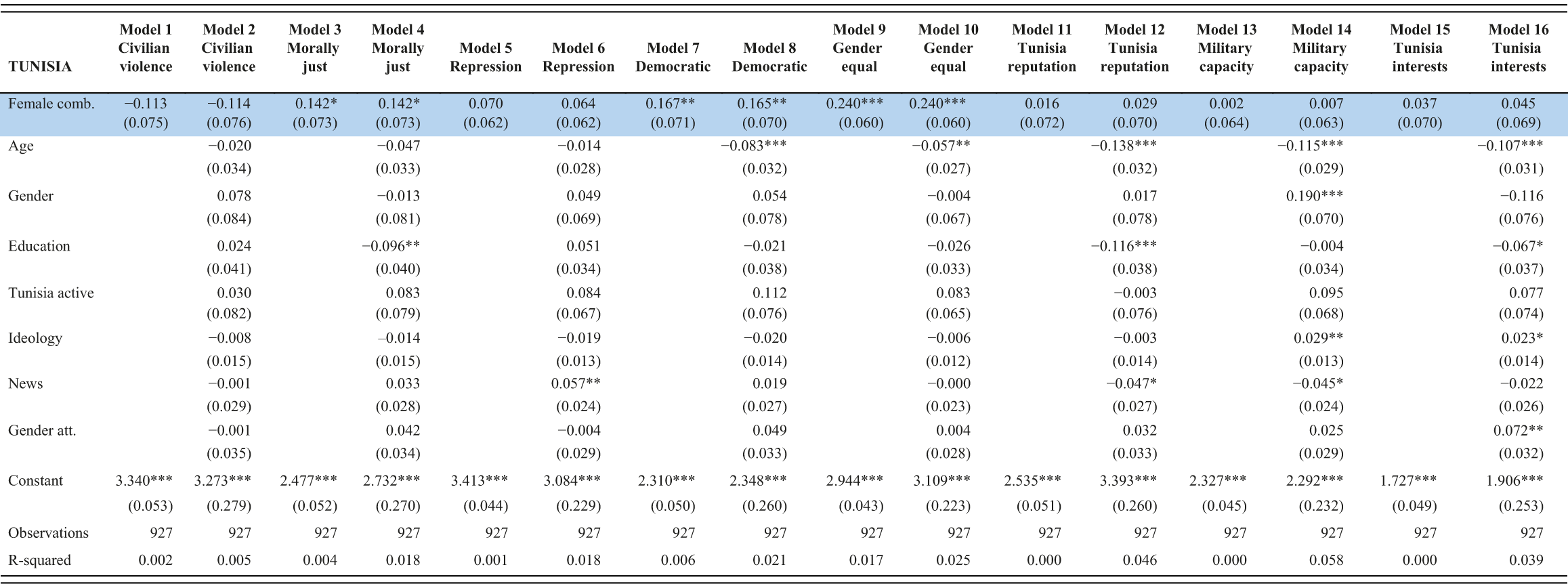

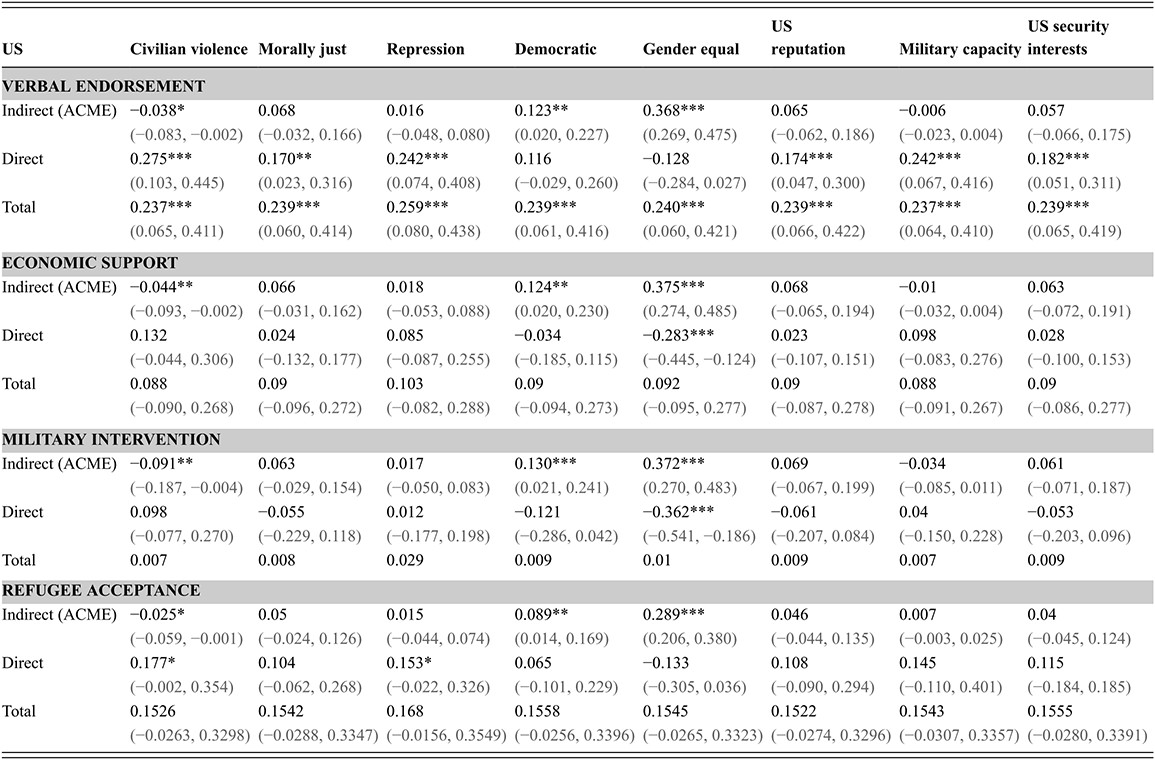

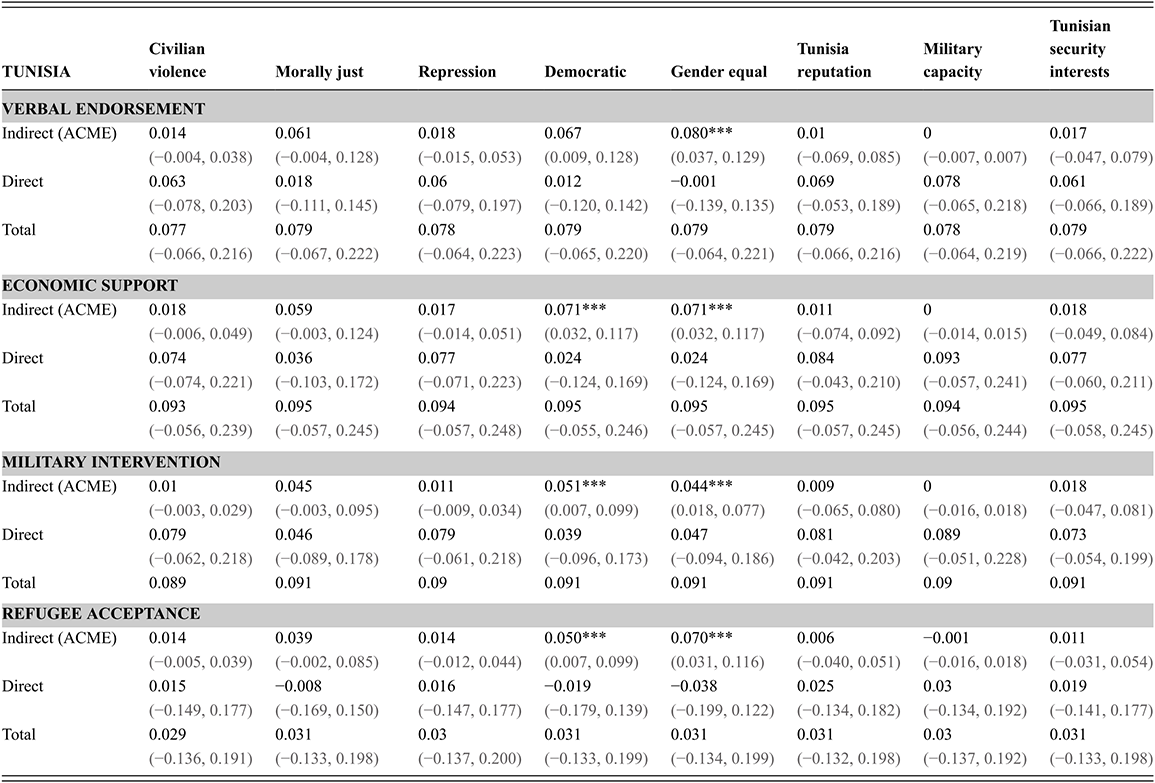

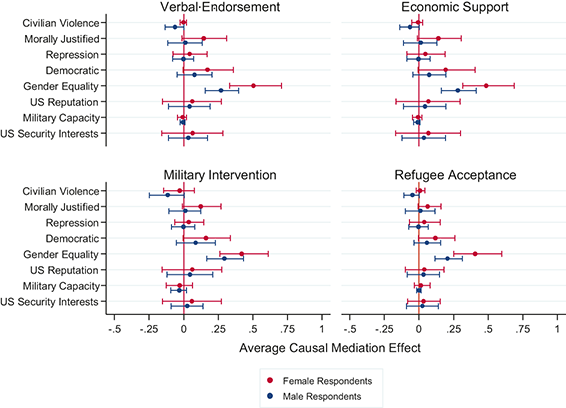

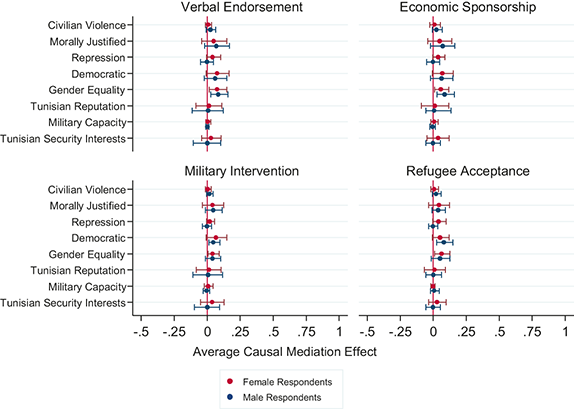

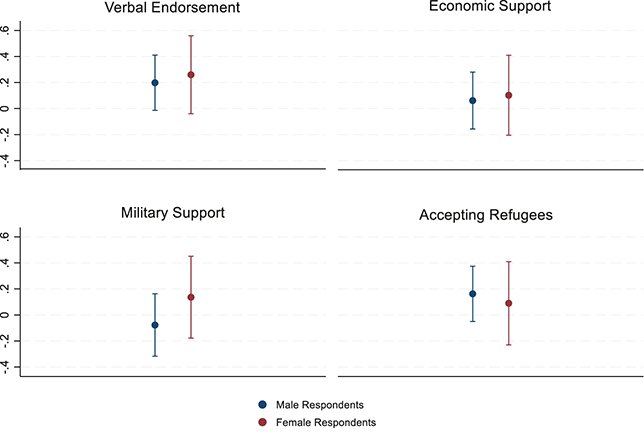

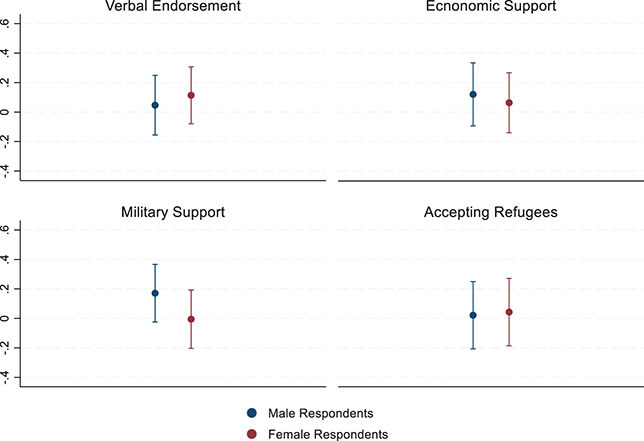

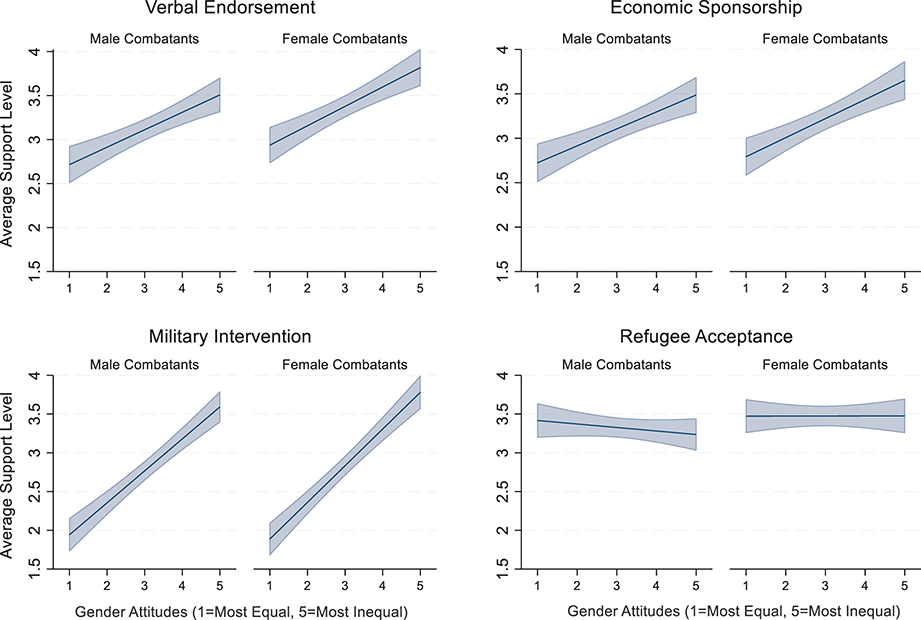

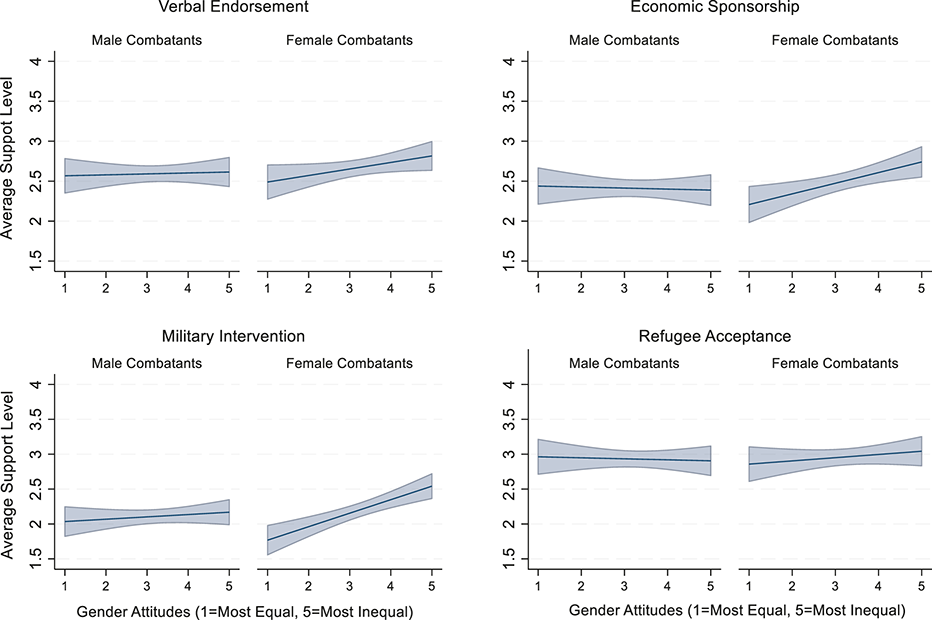

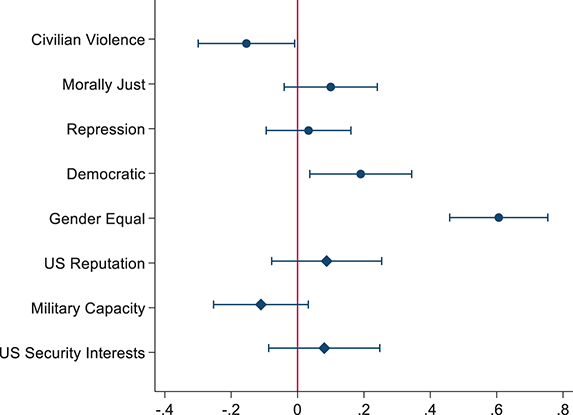

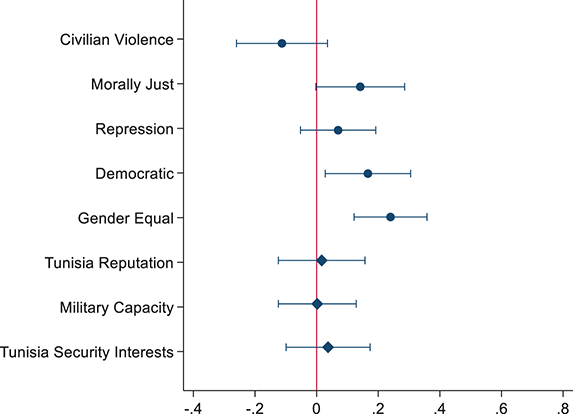

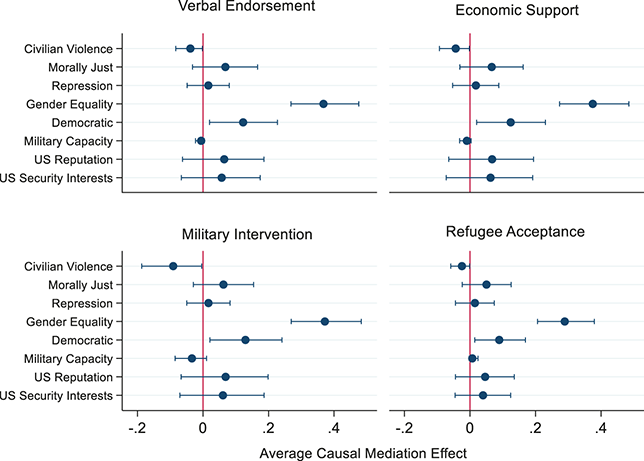

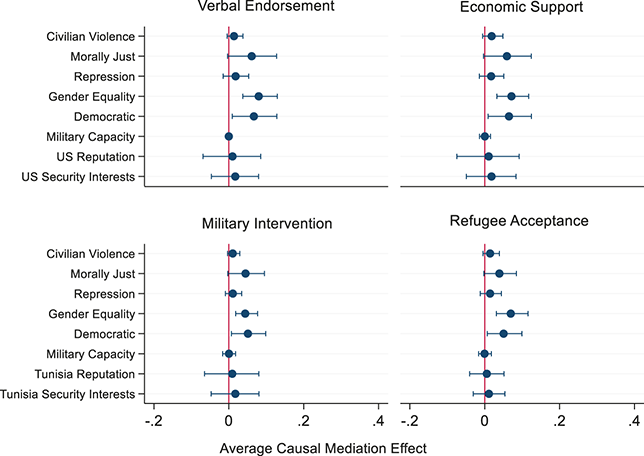

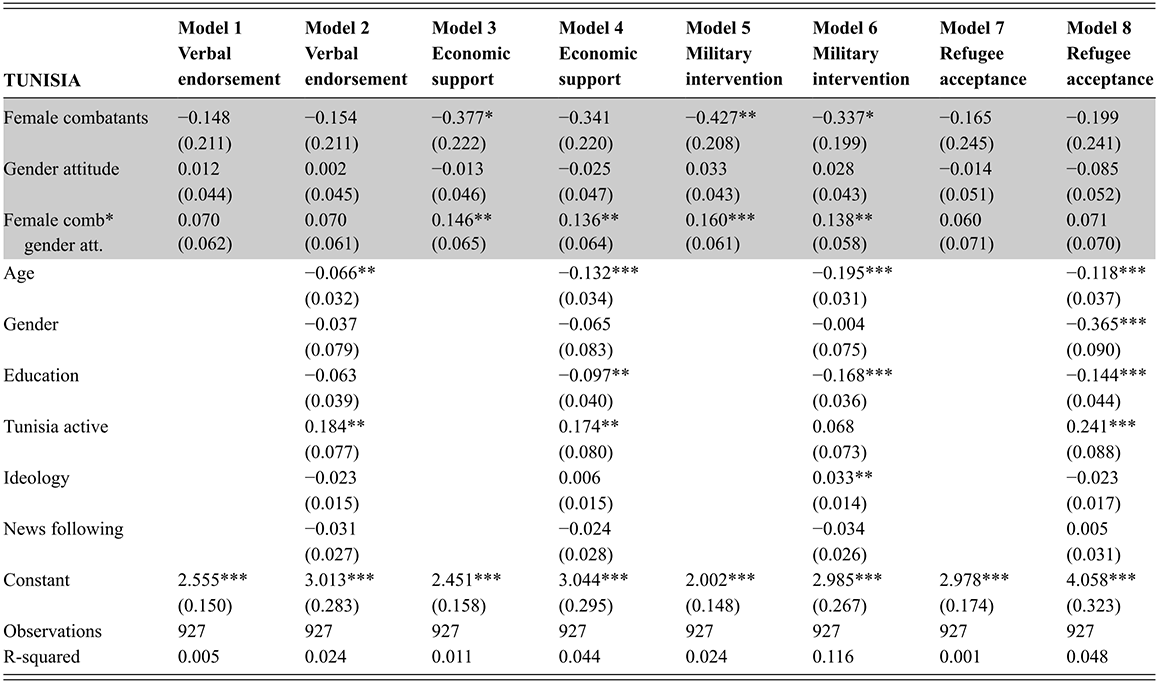

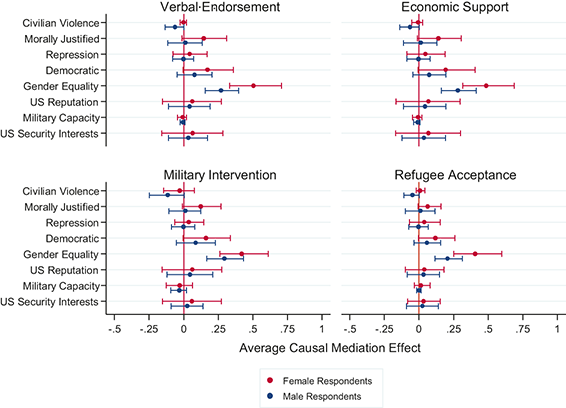

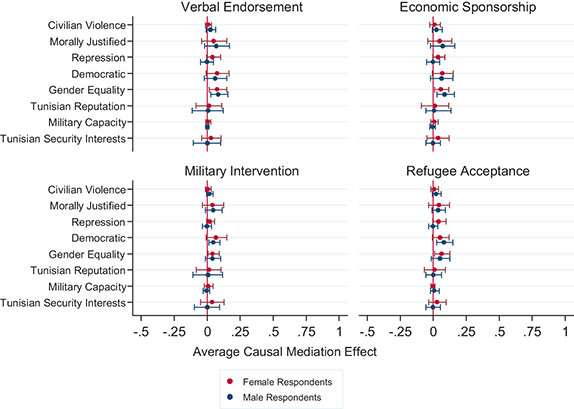

The results from these two different geographic and cultural contexts provide direct evidence that foreign audiences are more likely to support their government’s sponsorship of these groups when they know about female combatants’ presence. I find that this effect is particularly pronounced in the US, where citizens express stronger support for governmental endorsement – in terms of both verbal and financial backing – and are more open to accepting refugees from conflict zones when women participate in combat. The findings also reveal that both American and Tunisian respondents strongly perceive rebel groups recruiting women as more gender-equal and democratic. Additionally, they are more likely to view these groups as using less violence against civilians and see their armed struggle as more morally justifiable. These normative and humanitarian perceptions are central mechanisms driving public support for gender-diverse organizations. Contrary to expectations of backlash against women stepping into combat roles, there is no evidence of such a reaction. On the contrary, those with more traditional gender views – particularly among Tunisians – express stronger support for female combatants, challenging the assumption that conservatism uniformly resists women’s participation in conflict

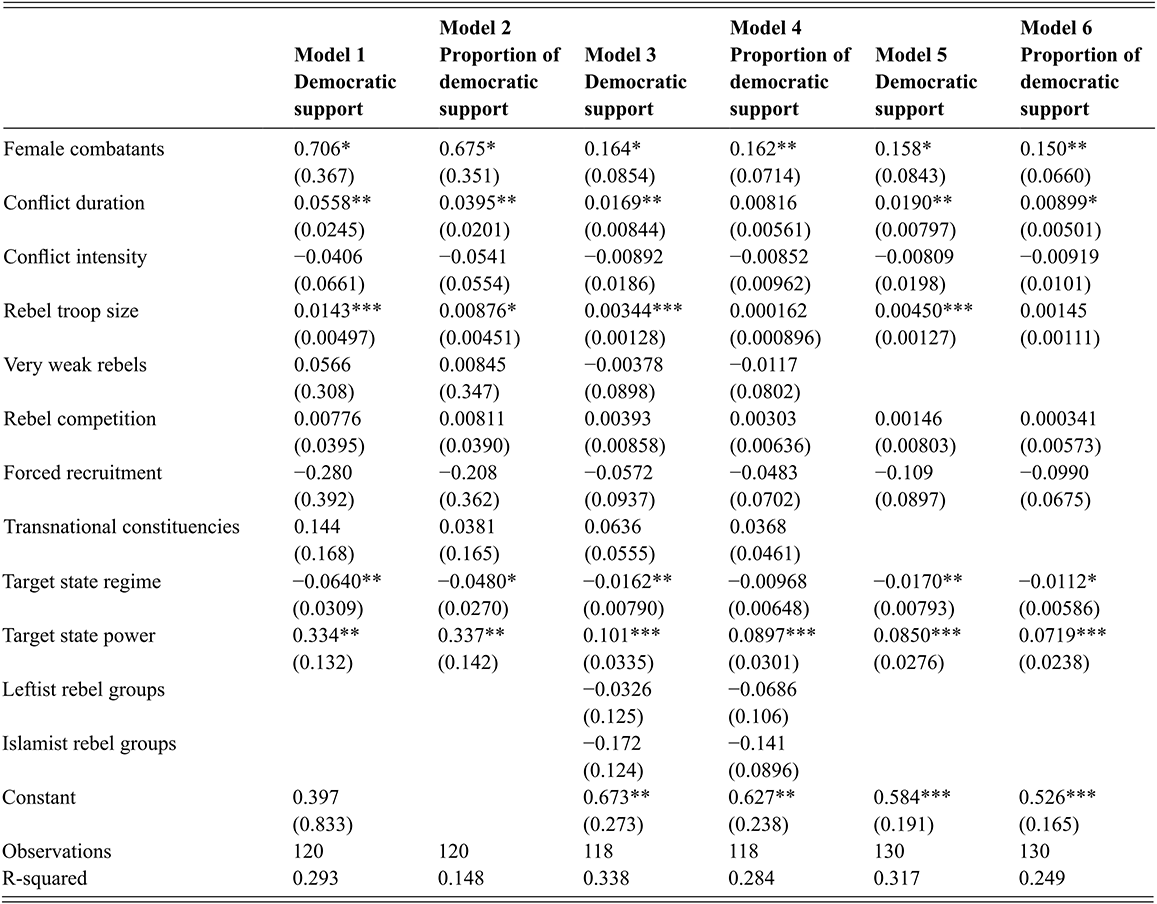

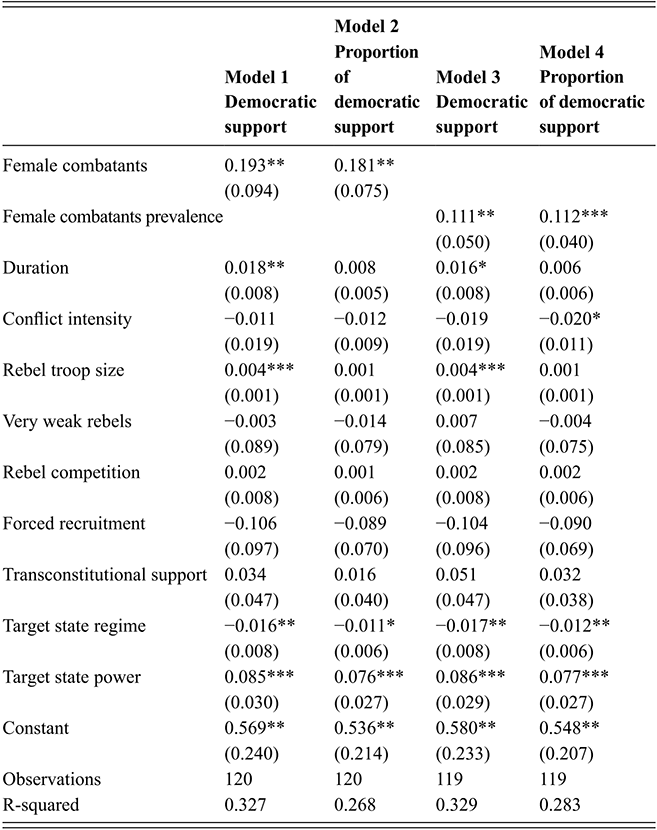

In the second part of the analysis, I examine whether these favorable attitudes influence actual foreign assistance from democracies. I focus on support from democratic states because leaders in these countries are more responsive to public opinion. As observed in the experiment, the presence of female fighters signals democracy and gender equality, making it easier for democratic leaders to justify support for these groups as consistent with national principles. Based on observational evidence from a global sample of rebel organizations between 1989 and 2009, I show that groups with female combatants are more likely to receive support from democratic states. Overall, evidence from two sets of analyses suggests that female participation in armed groups can attract tangible international benefits for rebel groups; sponsoring organizations with female fighters would be less likely to be considered an act of adventurism by foreign audiences, and the presence of female fighters can give the leaders an option of attaching a moral spin to the decision to support the rebel group.

The findings advance several key areas of research. First, this Element contributes both theoretically and empirically to the burgeoning literature on the outcomes of women’s participation in conflict (Başer, Reference Başer2022; Braithwaite and Ruiz, Reference Braithwaite and Ruiz2018; Brannon, Reference Brannon2023; Giri and Haer, Reference Giri and Haer2024; Loken, Reference Loken2024; Manekin and Wood, Reference Manekin and Wood2020; Wood and Allemang, Reference Wood and Allemang2022). Theoretically, it identifies specific mechanisms through which gendered outreach by rebel groups prompts external support, yielding tangible benefits. Empirically, it quantifies these benefits’ impact on foreign support through survey experiments with diverse audiences holding varying perspectives on women’s public roles. This way, it establishes the micro-foundations of how female combatants influence external support, positioning it as one of the first to examine female combatants’ role in shaping foreign government sponsorship of rebel groups.

A notable exception is Manekin and Wood (Reference Manekin and Wood2020), who show that female combatants can boost rebel legitimacy, particularly among US citizens, and help attract support from international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) and diasporas. Building on their work, this Element shifts the focus from legitimacy to exploring how female fighters shape both external public and governmental support through various causal mechanisms: instrumental factors, like sponsor states’ reputations and security interests; humanitarian concerns, like civilian harm and repression; and ideological cues, such as democratic or gender-equal imagery. Following their call to examine these dynamics across contexts, I analyze how gender norms and conflict exposure in both Western and Middle Eastern settings shape perceptions of gender-diverse groups, and show that these groups are more likely to gain support from democratic states. Overall, this Element goes beyond existing literature by dissecting how and why women insurgents affect foreign public opinion on different forms of conflict assistance and government support across contexts.

Second, I advance the scholarship on third-party involvement in civil wars by positioning rebel group membership, particularly gender composition, as a determinant of foreign support and parsing out the mechanisms linking them, highlighting the effect of membership in shaping rebel groups’ perceived characteristics. Recent experimental research suggests that the traits and behaviors of armed groups influence international audience perceptions, yet few studies have directly investigated how these attitudes are formed (Arves, Cunningham, and McCulloch, Reference Arves, Cunningham and McCulloch2019) and how these attitudes can translate into actual state support. This Element contributes to the literature on foreign policy attitudes by demonstrating that female combatants can increase foreign support for rebel groups by signaling humanitarian values and ideological moderation, aligning with research on the role of moral considerations in shaping public opinion on intervention (Kertzer et al., Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014; Kreps and Maxey, Reference Kreps and Maxey2018). It also adds to scholarship on the international appeal of rebel groups by showing how gendered signals, such as the inclusion of women, enhance perceptions of a group’s humanitarian profile, a factor crucial for securing international legitimacy and support (Jo, Reference Hyeran2015; Jo, Yi, and Barrett, Reference Hyeran, Joowon and Barrett2025; Stanton, Reference Stanton2016).

Third, by exploring female combatants’ role in public opinion, this Element furthers our understanding on the consequences of women’s participation beyond formal politics. Research on women’s political representation suggests that women politicians evoke positive perceptions regarding legitimate and honest governance (Barnes and Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2019; Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo, Reference Amanda, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Kao et al., Reference Kristen, Lust, Shalaby and Weiss2024). This Element shows that women’s participation incites similar positive perceptions in nontraditional realms of politics, even when they are perpetrators of violence and in traditionally masculine settings. Although rebel groups typically lack free and fair elections and tend not to prioritize gender rights, women’s participation makes their armed rebellion appear more democratic and gender equal. This Element suggests that these gendered views are so embedded that they are echoed in conflict settings and alter the conflict dynamics. Contrary to expectations of societal pushback against women breaking traditional norms by participating in combat, the results indicate that the presence of female combatants enhances group support, sometimes even more among those with conservative views. Hence, it extends research on gender stereotypes by showing that perceptions of good governance pertaining to female leaders in formal politics also apply to insurgencies, and that these gendered perceptions travel across formal politics and conflict settings.

Fourth, this Element advances and problematizes the broader empirical studies showing a positive association between women, gender equality, and peace. Studies show that states with higher gender equality are less likely to engage in conflict – referred to as the “gender equality–peace hypothesis” (Caprioli and Boyer, Reference Caprioli and Boyer2001; Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Caprioli, Ballif-Spanvill, McDermott and Emmett2009; Melander, Reference Melander2005; Wood and Ramirez, Reference Wood and Ramirez2018). Studies also show that women are typically less supportive of the use of force in foreign policy compared to men, even when controlling for factors like political partisanship, income, education, and age – referred to as the gender gap in support of war or as the “women–peace hypothesis” (Eichenberg, Reference Eichenberg2016; McDermott and Cowden, Reference McDermott and Cowden2001; Tessler and Warriner, Reference Tessler and Warriner1997). However, these attitudes are almost always assessed when perpetrators are male or presumed to be male – as the default image of a soldier or rebel is typically male. This Element complicates these hypotheses by revealing that violent organizations with female combatants are often perceived as embracing gender equality, leading people to support, and even endorse, military intervention on behalf of these groups, despite their violent tactics. In other words, gender equality can sustain support for armed groups and their violent tactics. This is puzzling because feminist consciousness – often considered central to women’s opposition to war (Brooks and Valentino, Reference Brooks and Valentino2011) – appears here to increase support for gender-diverse violent groups, challenging the assumption that gender equality and aversion to conflict go hand in hand.

Fifth, this Element contributes to the literature on gendered political preferences by showing that the gender gap in support of political violence disappears when combatants are women, which challenges the women–peace hypothesis. In other words, women are more prone to support using force when they see that their same-gender counterparts are engaged in combat. Despite female respondents’ lower baseline support levels for insurgencies, both male and female respondents show greater support when female fighters are involved, suggesting that gender representation in combat can shift women’s perspectives on conflict. The results suggest that the differences in individual gendered attitudes toward violence should not be evaluated independently from the gender of the perpetrator. These results highlight a complex relationship between gender and conflict, where the presence of female fighters and support for gender equality can foster, rather than diminish, support for violence. Overall, this examination of the relationship between gender roles, public opinion, and conflict responds to scholars’ calls to focus on mechanisms to have more refined theories about gender and political violence (Cohen and Karim, Reference Cohen and Karim2022).

In the rest of the Element, I first theorize about how the presence of female insurgents leads to a significantly different perspective on a rebel organization. Particularly, in Section 2, I explore how information on the gender of militants is processed to reveal positive or negative perceptions about the entire armed group. Then, I parse out the potential mechanisms through which traits associated with women can impact support for insurgency. In Section 3, I outline the original survey experiment design and present results from both the US and the Tunisian samples, demonstrating that the gender composition of rebel groups primarily influences foreign support by shaping perceptions of the group’s humane conduct, ideologies, and values. Section 4 describes the cross-national analysis and discusses the observational evidence, providing proof that groups with female fighters can attract more support from democracies. Finally, in Section 5, I discuss the primary contributions and their implications for research and policymaking.

2 Theoretical Framework

This section establishes the theoretical framework by addressing two questions: (1)Why would female militants’ presence affect public support? (2) How, or through which mechanisms, does female militants’ presence shape foreign audiences’ opinions? First, I outline the underlying premises of the theoretical framework, drawing from social psychology, foreign policy, and media studies literatures to explain why women’s presence should make a difference in public opinion. This framework helps us to understand how militants’ gender can become an important piece of information in making sense of the conflict dynamics, and why women’s visible presence can garner favorable perceptions even when they are just as willing as other groups to employ violent strategies that are frowned upon by foreign audiences. Second, I explore the mechanisms by which female militants affect foreign opinion, drawing on the scholarship from foreign conflict assistance and gender politics. In doing so, I discuss examples from media coverage and rebel activities to illustrate how these narratives converge to shape external perceptions of female militants.

2.1 Why Would Female Militants’ Presence Affect Public Support? Processing Information on Militants’ Gender

Militants’ gender can sway public opinion and impact decisions on sponsoring rebel groups. Foreign policy scholarship maintains that the information available to foreign leaders and the public is often disproportionate, with the latter having less access (Baum and Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2008). When making political judgments, people rely on the heuristic cues available to them to compensate for limited information (Popkin, Reference Popkin1994). Especially in conflict situations where uncertainty – about the goals, characteristics, strategies, and actions of actors – is pervasive, people use heuristics to infer the goals and natures of the warring parties.

The gender of militants is an important cue for audiences, to help them form beliefs about the conflict about which they lack context. All social identities – such as racial, ethnic, and gender – are associated with a set of norms that prescribe the expected behavior for members of that category. These norms and expectations influence behavior because they affect individuals’ preferences. The perceived social identity of rebel members thereby works as a shortcut, informing people about the characteristics of the conflict environment, such as how they behave, what they are fighting for, and what they are up against.

That said, women constitute a smaller fraction of combatants in contemporary rebellions. While their noncombatant roles are more common, they participate as fighters in about one-third of armed movements, with 15 percent of rebel groups having a dedicated women’s wing with frontline units exclusively for female fighters (Matfess and Loken, Reference Loken2024; Wood and Thomas, Reference Wood and Thomas2017). Despite their relatively limited presence, how can female combatants convey so much about the entire group’s character, shaping opinions on backing the group?

Social psychology literature suggests that individual traits can serve as powerful cognitive shortcuts for identifying the whole group to which those individuals belong, a phenomenon known as “entitativity” (Campbell, Reference Campbell1958). Entitativity refers to the perception of a collection of people as bonded together in a meaningful unit (Crawford, Sherman, and Hamilton, Reference Crawford, Sherman and Hamilton2002). This perception of group unity prompts observers to use the available information to infer dispositional qualities in the target group, form a cohesive impression of the group, assume consistency across situations, and attempt to resolve any inconsistencies in the information about the group (Hamilton and Sherman, Reference Hamilton and Sherman1996). For instance, spectators at a soccer game, though not an organized group, are often seen as having high entitativity; people attribute traits like aggressiveness to all fans based on the actions of a few, viewing them as a unified – and aggressive – group (Campbell, Reference Campbell1958). Entitativity is a crucial precursor to stereotyping, especially for outgroups with so-called essential identities that are perceived as fixed, like gender or race. This is particularly the case when only a few individuals are visible in a field (e.g., women in the military), where they stand out as “tokens” (Agadullina and Lovakov Reference Agadullina and Lovakov2018; Crawford et al., Reference Crawford, Sherman and Hamilton2002).

In conflict settings, the entitativity mechanism leads to stereotyping that extends characteristics associated with women to the entire rebel organization. The involvement of women as perpetrators of violence disrupts the conventional view of women as inherently peaceful. This creates cognitive inconsistency. Observers may resolve this inconsistency by projecting stereotypical female traits onto the entire rebel group, simplifying complex conflict dynamics into familiar gendered beliefs.

This stereotype projection can take two forms: Observers may attribute traditionally “feminine” traits, such as compassion or nurturance, to the group, assuming that women’s presence makes the group more peaceful. Alternatively, women’s violent roles may clash with gender norms, leading to perceptions of female combatants as deviants and their groups as morally corrupt. How the group is ultimately perceived – favorably or unfavorably – depends on (i) the pervasiveness of gender roles, (ii) the media framing, and (iii) the rebels’ international outreach activities.Footnote 2 The pervasiveness of embedded gender norms suggests that people are likely to assign their preexisting gendered assumptions to the rebel group upon seeing women as part of it, even absent information – that is, with a lack of media framing or strategic rebel propaganda. That said, media framing and rebels’ intentional gendered strategies solidify these perceptions. I will now unpack each of these factors.

First, the pervasiveness of gender roles is one way that the process of stereotype projection to an entire group operates. The link between women, peace, and morality is so deeply ingrained that it underpins national identity and shapes notions of citizenship (Peterson, Reference Peterson1992). Scholars posit that concepts of state and citizenship cannot be understood without considering gender; women are envisaged as moral authorities, entrusted with guarding and passing national identity to generations (Yuval-Davis, Reference Yuval-Davis1997). People readily rely on these embedded norms even more in contexts with ambiguity about actors’ responsibilities. Ambiguity encourages cognitive distortion aligned with traditional gender norms (Heilman and Haynes, Reference Heilman and Haynes2005), reinforcing perceptions that women are more peaceful and moral than men. This reinforces the “peaceful woman” stereotype, even when women engage in violence, and shapes beliefs about the rebel group’s behavior (as more peaceful), helping people solve the inconsistency in seeing women as part of a violent group.

Second, media framing amplifies these perceptions by leveraging gendered frames. The mainstream media, along with elites, plays a crucial role in shaping public attitudes toward foreign policy (Entman, Reference Entman2003). The media reports news through specific frames that cue the receiver to contextualize events, using selective issues, words, and photographs to influence how the story is perceived. Despite the diversity of contemporary media outlets, framing usually aligns with entrenched audience predispositions, as the media seeks to satisfy public demand as a strategic actor (Baum and Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2008). Framing a news item is most potent when it is culturally congruent with schemes that most members of society habitually employ (Entman, Reference Entman2003), and emotionally charged news influences foreign policy attitudes more than sole information (Gadarian, Reference Gadarian2010).

While the demand for foreign policy–related news is typically low, especially in the US, several factors capture public interest, such as casualty levels and elite discord (Baum and Potter, Reference Baum and Potter2008). The presence of female fighters is one such case that prompts public attention. They garner more sensational and emotional media coverage than men, which increases their propaganda value for rebels (Nacos, Reference Nacos2005). For instance, in recent conflicts in Syria and Iraq, women have been “hypervisible,” becoming central figures in media coverage (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2018).

Despite pursuing different objectives, mainstream media reporting and rebel outreach strategies often rely on similar frameworks to engage the public; both reinforce and are shaped by existing gendered expectations. In conflict, when women participate as combatants, the Western media in particular portrays them as mothers, victims, or feminists in romanticized narratives that evoke emotions aligned with socially resonant gendered themes (Sjoberg and Gentry, Reference Sjoberg and Gentry2007; Toivanen and Baser, Reference Toivanen and Baser2016). This framing corroborates the gendered framing by rebel groups, emphasizing women’s bravery, motherhood, and peacefulness (Rajan, Reference Rajan2011). This depiction reinforces the “peaceful women” stereotype even when women engage in violence; it downplays the severity of their violent acts, portraying them as victims of harsh conditions (more so than males) or as advocates for gender equality (detailed in Section 3).Footnote 3

Third, rebel groups are usually aware of the propaganda value of female militants, and strategically deploy them for international support. Typically, groups recruit women not just for international outreach but for other advantages as well, including expanding the labor force, building ties with locals, and, as they can more easily bypass security checks, aiding covert operations such as espionage, recruitment, and weapons transport. However, groups are also aware of women’s outreach advantages and make strategic choices to attract external support.

For example, the LTTE leadership was keenly aware of the impact that armed women could have on foreign perceptions of the movement’s objectives and actively promoted them through various media (Wood, Reference Wood2019). Its international branches produced and distributed documentaries, published books and magazines highlighting women’s roles, and arranged media interviews with female militants (Brun, Reference Brun2005). United Nations reports revealed that Nepal’s Maoists inflated female militants’ numbers to almost double for international propaganda purposes (Ortega, Reference Ortega2010). Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM) in Indonesia coordinated with Western media to promote its limited number of female combatants to foreigners (Manekin and Wood, Reference Manekin and Wood2020). The leader of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK – Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê, in Kurdish), Öcalan, also recognized the role of women in mobilizing international support. From its early years, the PKK cultivated ties with global women’s organizations, securing the women’s military unit’s (YAJK) participation in the 1995 UN World Conference on Women (Başer, Reference Başer2022). Öcalan frequently credited women with shaping global perceptions, emphasizing in the PKK’s official bulletin that they elevated the group’s appeal and image in Europe and the Middle East (PKK, 2001: 7). He specifically highlights the Kurdish women’s resistance against ISIS as a turning point, stating that their courage significantly amplified international attention for PKK (Başer, Reference Başer2022).

These examples illustrate how the media, rebel strategies, and public attitudes interact. Rebels leverage gendered outreach to attract support, while audiences, influenced by ingrained gender biases, interpret female militants in ways that align with preexisting perceptions. Since media portrayals and rebel messaging are rarely neutral, their interaction likely amplifies the effect of female combatants far more than controlled experimental settings can capture.

However, not all women would give the same impression. A group’s ideology and whether it shares an affinity with one’s country, when such information is available, are important factors shaping perceptions. I expect the theorized relationship to be weak or absent in cases such as women in veils, women depicted as suicide bombers, and abducted women. The veil symbolizes Islam, and female militants linked to groups espousing extremist interpretations of Islam are usually vilified or viewed as mentally ill, as depicted in racialized portrayals in the Western media. Female suicide bombers killing civilians tend to be evaluated negatively compared to women, for instance, engaging in guerrilla warfare. They are often portrayed as mad, or monsters, drastically deviating from feminine nurturing norms (Gentry and Sjoberg, Reference Gentry and Sjoberg2015). These portrayals vilify rather than humanize them, dampening their appeal to audiences. Also, the dynamics discussed here apply more to women who join armed groups voluntarily, as abducted women are less likely to gain support by signaling peace, nonviolence, or gender progressiveness. Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) gained notoriety for abducting thousands, forcing them into child soldiering or sexual slavery, which undermined support. Yet, without such information, people would likely assume voluntary participation.Footnote 4

Women in noncombatant roles are less likely to attract international attention or support because women serving as cooks, cleaners, nurses, or messengers, while essential to the functioning of the group, do not challenge traditional gender norms in the same way as combatants. They are less likely to be framed as markers of progressivism, empowerment, or humanitarian concern than the combatant women who visibly break norms. Noncombatant women are also less likely to raise negative perceptions about military capability, as they do not engage in fighting. Hence, they may evoke weaker emotional or ideological reactions – whether about equality or concern about military power. Overall, while their roles are crucial, they remain largely out of the international spotlight and are less likely to change public opinion. While these are plausible, further research is needed to explore the impact of these various forms of women’s participation in conflict on international audiences. For instance, some noncombat roles, such as nurses, can still trigger humanitarian emotions, especially if they are framed well by advocacy campaigns and rebel lobbyists. This Element, however, focuses on women in combatant, rather than noncombatant, roles, where their involvement in violence sharply contradicts traditional gender norms.

Another question is to whom the rebels are signaling and whether their strategies vary by audience. Rebels can leverage different reputation-building strategies to appeal to different constituencies (Akcinaroglu and Tokdemir, Reference Akcinaroglu and Tokdemir2018). For instance, service provision strengthens legitimacy among locals, while compliance with international law boosts international standing. However, they can seek legitimacy from both, making the efforts interconnected. Rebels seeking local authority also engage with humanitarian actors, as international backing weakens state narratives (Jo et al., Reference Hyeran, Joowon and Barrett2025). In this context, the gender norms of their audience would shape how rebels market female combatants, as they would tailor narratives to align with their targets’ values. For example, the PKK emphasized its gender-progressivism in engaging with Western democracies, while embodying traditional norms in its local communications, portraying women as primarily mothers and symbols of innocence to raise sympathy and reinforce ceasefire credibility (Başer, Reference Başer2022). Szekely (Reference Szekely2020) contends that, in the Syrian Civil War, rebel groups and states deployed female combatants as a cost-effective means of signaling alignment with the US and differentiating themselves from ISIS. They also manipulated the visibility of women, emphasizing or minimizing their presence to appeal to different audiences. As such, we would expect rebels seeking support from liberal democracies to be more likely to convey egalitarian messaging than those courting actors like Saudi Arabia, where such narratives hold less appeal.

Another question is whether there’s a gap between rebels’ marketing strategies and the experiences of female militants. Organizations can embrace gender equality as both a normative commitment and a strategic tool (Başer, Reference Başer2022). Even without genuine commitment, the presence of women fighters can project an egalitarian image, but this risks backlash if seen as inauthentic. Scholars disagree on whether armed groups can truly cultivate gender emancipation. Sixta (Reference Sixta2008) views female militants as First Wave feminists, arguing that they resist triple oppression – Western, societal, and organizational. Others maintain that even groups promoting gender equality often remain patriarchal, abandon reforms post-conflict, and expose women to new vulnerabilities (Mazurana et al., Reference Mazurana, McKay, Carlson and Kasper2002). Recent research shows mixed outcomes: group-level studies find that women can advocate for designing and implementing inclusive peace deals (Brannon and Thomas, Reference Brannon and Thomasforthcoming; Thomas, Reference Thomas2024), while individual-level accounts, like in FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), highlight how women’s newfound greater agency remains constrained by collective goals and patriarchal (Barrios Sabogal, Reference Sabogal and Camila2021). This agency is also shaped by intersectional factors like class, ethnicity, and education, as in the Nepal Maoists (Giri, Reference Giri2023). This Element doesn’t aim to judge whether rebels’ gendered messaging is genuine or if female fighters are actually empowered, but it argues that associations between women and values like equality, peace, and moderation, amplified by media and rebel narratives, can shape support for their groups.

Overall, insights from social psychology, public opinion on foreign policy, and the media indicate that information about militants’ gender should systematically influence public opinion. It follows that the gender of rebel membership matters for conflict dynamics, as the presence of women makes a difference in how rebel groups are perceived. In the next section, I outline pathways through which women and their rebel groups can shape perceptions and influence foreign support, walking through examples from media framing and rebel outreach strategies.

2.2 How Does Female Militants’ Presence Shape Foreign Audiences’ Opinions? Mechanisms of Support for Female Combatants

After establishing why messages of women combatants would shape public perceptions differently than male insurgents, this section explains how, or through which mechanisms, they affect foreign audience’s opinions. Public support for foreign conflict assistance is influenced by both normative and instrumental concerns (Holsti, Reference Holsti2004). Normatively, individuals are more likely to support interventions framed around humanitarian values – such as protecting civilians or aiding groups perceived as morally just or those linked to their ideologies and core values (Kertzer and Zeitzoff, Reference Kertzer and Zeitzoff2017; Kreps and Maxey, Reference Kreps and Maxey2018). On the other hand, instrumental support is often contingent on expected national benefits or gains on the ground (Gelpi, Feaver, and Reifler, Reference Christopher, Feaver and Reifler2009).

The traits associated with women can potentially impact foreign public support for the insurgency through both normative and instrumental concerns, which can pull the support in either direction. Normatively, groups with female combatants increase public support as they are considered to exercise moderation, pursue just goals, and/or support gender equality. Yet, instrumental concerns can either increase or decrease support. Specifically, citizens’ concerns about their country’s international reputation can increase support, while doubts about practical gains may decrease it, as women are often viewed as unfit for combat.

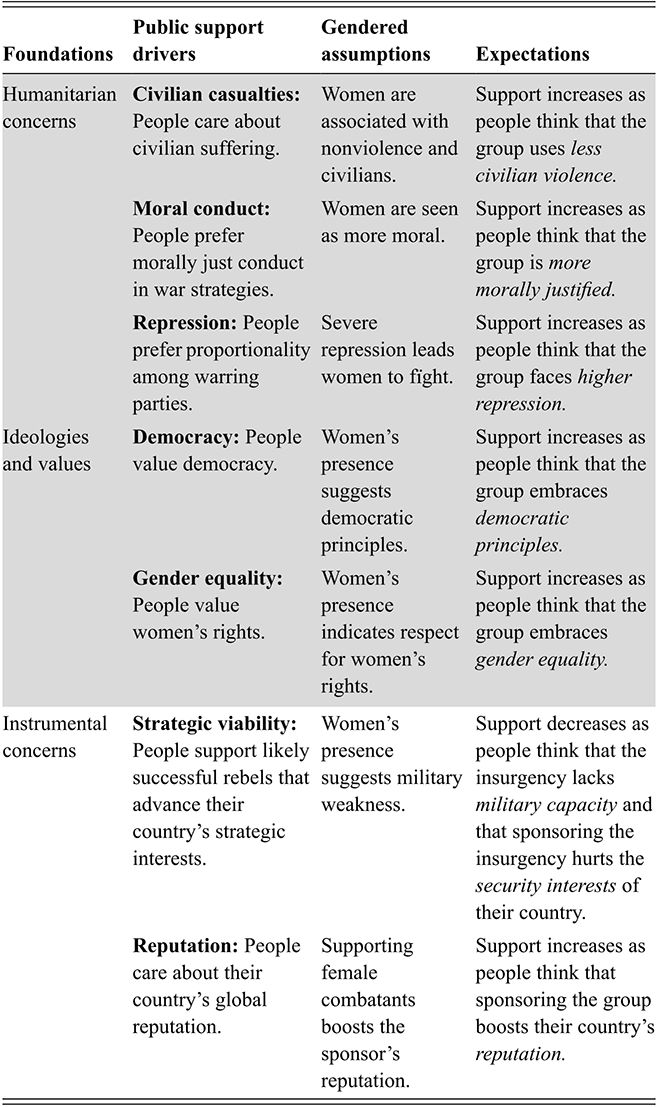

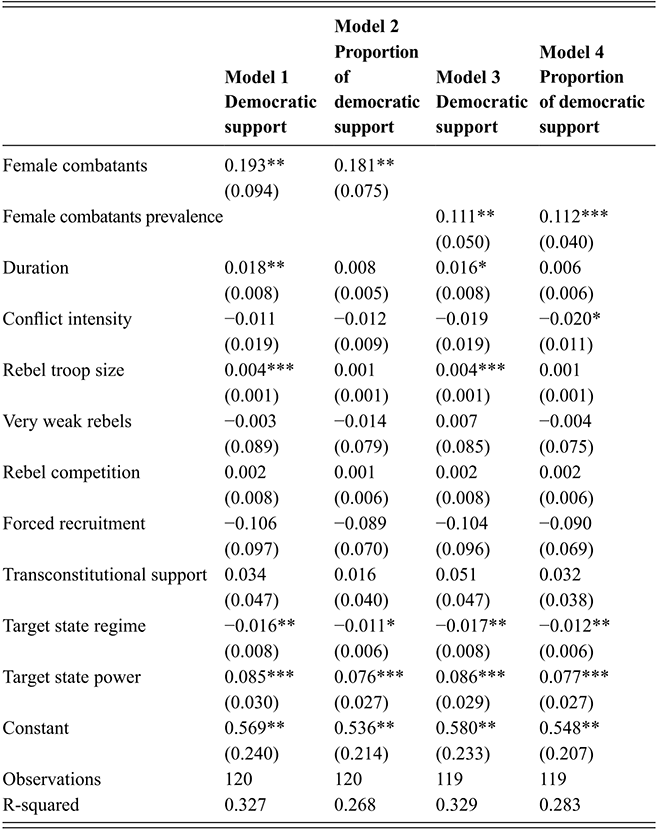

Building on scholarship on foreign conflict assistance and gendered conflict dynamics, I outline mechanisms through which female combatants can shape public support for foreign armed movements in three groups: (1) humanitarian concerns, (2) ideologies and values, and (3) instrumental concerns. I divide the normative concerns into the first two categories, as doing so clarifies distinct pathways through which gendered assumptions can shape support – namely through ethical obligations surrounding conflict dynamics versus alignment with the group’s values. Table 1 outlines the underlying factors driving foreign public support for conflict assistance, the gendered assumptions amplifying these factors, and the expected support trends for groups with female combatants based on these drivers. To the best of my knowledge, no studies have systematically tested these perceptions about female fighters or how these perceptions increase or decrease public support for their government’s backing of the group.

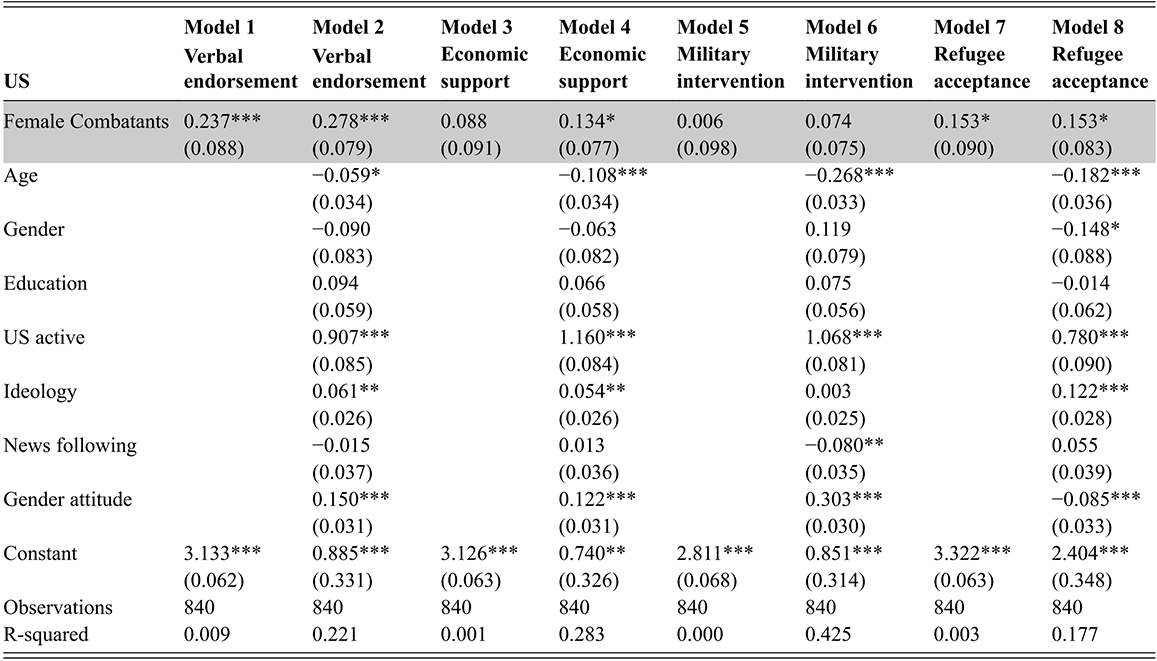

Table 1Long description

The table lists mechanisms across humanitarian concerns, ideologies and values, and instrumental concerns. For each category, it highlights core public support drivers, such as concern for civilians, morality, repression, democracy, gender equality, strategic interests, and national reputation, and then shows how women fighters modify these beliefs. Each row concludes with the expected effect on public support, indicating when gendered perceptions increase or decrease support for insurgent groups. Women’s presence can make groups seem less violent, more moral or democratic, and more reputation-enhancing, hence increase support, but can also raise doubt about military strength, which may decrease support.

2.2.1 Humanitarian Concerns

Humanitarian and moral imperatives influence citizens’ support for war (Tomz and Weeks, Reference Michael R. and Weeks2020). Among these concerns, civilian casualty, moral war conduct, and proportionality among warring parties stand out as they reflect key war norms, and women’s involvement makes these concerns even more pronounced. Due to women’s image as nonviolent, civilian, victim, and moral figures, their presence can increase support for their armed rebellions.

The first mechanism under the humanitarian-concern category is about harm inflicted upon civilians in combat zones. Protection of civilians is an international norm; Geneva Conventions require fighting parties to strictly refrain from targeting civilians. Research shows that civilian casualties reduce support for use of force (Gartner, Reference Gartner2008; Kertzer et al., Reference Kertzer, Powers, Rathbun and Iyer2014).

People may associate women with civilians and nonviolence, which can boost support for female combatants. Prevalent gender norms deem men to be the natural warriors while attributing victim or civilian roles to women. The phrase “women and children” best exemplifies how women are framed as civilians, innocent, and in need of protection, akin to children. Strategically employed by INGOs to attract donors (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2005), the phrase suggests that women lack agency and share children’s vulnerability to violence, rather than being potential fighters. These presumptions can lead people to evaluate groups recruiting women as less likely to attack civilians, which can increase support for their groups.

The second mechanism through which women can impact war support is proportionality of the use of force among warring parties, or state repression in civil wars (Hurka, Reference Hurka2005). Walzer’s (Reference Walzer1977) classic work on war ethics highlights the proportionality principle, where warring parties should refrain from using excessive or disproportionate force vis-à-vis their military objective. Research suggests that citizens also care about proportionality in conflict, shaping their support for the use of force (Dill, Sagan, and Valentino, Reference Janina, Sagan and Valentino2022).

Public sensitivity to proportionality suggests that perceptions of force’s scale matter. Traditional norms associate women with motherhood, passivity, and innocence, rather than being active political agents, so their involvement in combat signals extraordinary circumstances. When women take up arms, it indicates that repression is so severe that even the most passive members of society are compelled to fight. Scholars presume that this perception of disproportionate force against women helps groups with female combatants build legitimacy and mobilize support (Loken, Reference Loken2021; Viterna, Reference Viterna, Bosi, Demetriou and Malthaner2014). This, in turn, can raise public sympathy for the group, as observers may view women’s participation as evidence of disproportionate state violence, increasing favorability toward the group.

The third mechanism is shaping perceptions of the group’s cause as morally justified. Research shows that public support for US foreign policy decisions rises when framed around supporting human rights, and beliefs about the moral righteousness of conflict intervention drive support for foreign assistance more than strategic concerns (Kreps and Maxey, Reference Kreps and Maxey2018).

Women are typically considered the “fairer sex,” which can shape people’s understanding of conflict dynamics, as it does in politics. People tend to view female politicians as less corrupt and more honest than their male counterparts, with their involvement enhancing the legitimacy of political decisions (Barnes and Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2019; Clayton et al., Reference Amanda, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Similarly, female-led parties are perceived as more moderate than male-led parties (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2019). These assumptions extend to conflict settings, where women are believed to have a similar moderating effect on rebel group perceptions (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2009). Perceptions linking women with moral behaviors can lead people to view groups with female combatants as fighting a more moral cause than their male-dominated counterparts, bolstering support for the group.

Media Coverage and Rebel Outreach: How can women maintain their nonviolent, victim, and ethical image even when they are perpetrators of violence? Media portrayals, often aligned with rebel outreach strategies, play a key role. Especially the Western mainstream media’s framing of women militants reinforces the existing perceptions associating women with morally desirable notions. For example, a New York Times article on the uprising against Qaddafi emphasizes the legitimacy and inclusivity that the women bring to the armed rebellion: “Perhaps most important, women here participated in such large numbers they helped establish the legitimacy of the revolution, demonstrating that support for the uprising has penetrated deep into Libyan society” (Barnard, Reference Barnard2011). Another news title in the Independent emphasizes the motherhood of rebels: “Female Yemeni fighters carry babies and machine guns at the anti-Saudi rally” (Pasha-Robinson, Reference Pasha-Robinson2017). Sputnik’s choice to include an interview of a male insurgent fighting in the Syrian Civil War illustrates how motherhood traits are attached to female fighters, even though the organization effectively bans motherhood by prohibiting sexual relationships: “There are true heroes among women. They display courage on the battlefield while giving birth. That is what infuses a woman with greatness. Allah gave them qualities men do not have” (Sputnik International, 2015).

Toivanen and Baser (Reference Toivanen and Baser2016) find that the French and the British media portray Kurdish female fighters as selfless defenders, using violence only as a last resort, thus underscoring the severity of repression. The Western media often frames non-Western women as needing liberation (Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2006), while novels depict female terrorists sympathetically, balancing their roles as both life-givers and life-takers through maternal compassion (McManus, Reference McManus2013). These portrayals suggest that the Western media tends to present female rebels favorably, appealing to emotions and reinforcing existing beliefs, thus enhancing their propaganda value.

Rebel groups align with these portrayals to evoke humanitarian concerns, often leveraging motherhood to soften perceptions of violence (Viterna, Reference Viterna, Bosi, Demetriou and Malthaner2014). They use imagery of mothers holding rifles alongside babies to humanize and justify their cause, emphasizing women’s perceived nonviolence (Loken, Reference Loken2021). For example, a Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) poster depicts an armed woman as “woman, mother, and fighter on the path to liberation,” prioritizing motherhood as her revolutionary identity. This rhetoric spans the political spectrum, with leftist groups like Nicaragua’s Sandinistas and South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) employing it despite not advocating traditional gender roles. Similarly, religious fundamentalist groups like Hamas and Hezbollah stress motherhood, despite rarely deploying women in combat (Loken, Reference Loken2021).

Rebel groups also frame their women fighters as righteous defenders and protectors of vulnerable women. The LTTE highlighted its role in shielding women from sexual violence by Sri Lankan forces (Stack-O’Connor, Reference Stack-O’Connor2007). In 2013, FARC launched Mujer Fariana to depict its women as empowered fighters defending the oppressed, while al-Qaeda produced a magazine called Al Shamikha (“Majestic Woman”) to humanize their cause and downplay violent tactics.

To sum, just as stereotypes in traditional politics shape perceptions of female leaders – viewed as emotional, caring, passive, and gentle versus men as aggressive and forceful – similar perceptions (reinforced by media portrayal and rebel outreach activities) can lead to underestimating civilian targeting, overestimating state repression, and perceiving a more moral cause when female combatants are involved. These favorable perceptions can increase support for gender-diverse armed groups.

2.2.2 Ideologies and Values

Ideologies and values constitute another group of factors that influence public views on foreign policy; people are more likely to support conflict involvement abroad if foreign actors align with their beliefs (Chu, Reference Chu2021). Among these values, democratic principles and gender equality particularly resonate with citizens in democracies and autocracies – though perhaps to a lesser extent. I argue that the presence of women in rebel groups signals these values, suggesting a commitment to democratic principles and respect for women’s rights, which can bolster public support for their government’s sponsorship of these groups.

First, democratic principles have become an essential source of these shared ideologies and values among citizens, shaping their attitudes toward support for the use of force abroad. People in democracies are more supportive of intervening on behalf of democracies than of autocracies, and more averse to attacking democracies – this sets the foundation of the democratic peace theory (Tomz and Weeks, Reference Tomz and Weeks2013). At the same time, women’s rights have been associated with democracies. Women’s inclusion in political decision-making is seen as essential to democratic governance; it ensures that half the population is represented in decision-making, and enhances perceptions of the fairness, inclusivity, and responsiveness of democratic institutions (Barnes and Beaulieu, Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2014; Clayton et al., Reference Amanda, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). These values are reflected among the international community too. As gender equality rose on the global agenda, democracy promotion and foreign aid efforts began to emphasize women’s representation. Women’s political participation and democratic norms have become so closely bundled that even authoritarian regimes adopt gender quotas to enhance their democratic reputation in the international arena. Research shows that foreign audiences are indeed receptive to this image; they consider countries with higher women’s representation to be more democratic, even when countries lack elections (Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg Reference Bush, Donno and Zetterberg2024).

This association between women’s inclusion and democratic values can extend beyond formal politics into armed conflict. Just as women’s representation has become shorthand for democracy in states, the presence of women in rebel groups may signal a similar commitment to democratic norms – whether genuine or strategic. International observers, including donors, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and foreign publics, can view women’s participation as a reflection of inclusive governance and a rejection of authoritarian structures, especially where insurgents fight against autocracies. As such, gender inclusion serves not only as a military or ideological asset but also as a low-cost tool to project democrative values, differentiate from rivals, and appeal to foreign allies. This was evident in the Syrian Civil War, where gender ideology became a key cleavage: groups that included women used this to signal democratic and progressive credentials to potential domestic and regional allies, while those that excluded women were associated with authoritarianism and linked to actors like the Assad regime or ISIS (Szekely, Reference Szekely2020).

Given that rebel groups often lack democratic structures like elections or checks and balances, cues such as gender inclusion may become especially salient; observers may rely on the presence of women in leadership or combat roles to infer a group’s ideologies and post-conflict intentions. While how civilian treatment and international law alignment enhance rebel legitimacy is examined, the potential of female combatants to signal democratic alignment has not been explored. Examining whether women’s participation conveys democratic values, even within rebel groups typically governed by hierarchical and authoritarian structures, offers a compelling test into the symbolic power of gender inclusion.

Gender equality is another value that can shape conflict assistance. Although the literature has yet to directly address gender equality as a factor in conflict assistance, related studies demonstrate that women’s rights shape foreign aid trends (Dietrich et al., Reference Dietrich, Donno, Fleiner and Iannantuoni2025) and public attitudes toward foreign actors. Countries that institutionalize political gender equality are considered more deserving of foreign aid (Bush and Zetterberg, Reference Bush and Zetterberg2021; Bush et al., Reference Bush, Donno and Zetterberg2024), and countries that rely on Western foreign aid, despite their questionable human rights records, are more willing to adopt gender quotas to signal their alignment with gender progressivism (Edgell, Reference Edgell2017).

A similar mechanism could likely work for gender-diverse groups, but is yet to be tested. Women’s inclusion in rebel groups can make people think that their group embraces and fights for gender equality. While rebels typically do not mobilize around gender equality as a primary concern, first seeking rather to achieve greater autonomy or gain political and economic concessions, the presence of women fighters gives the groups a chance to frame their goals in a way that resonates with those concerned with women’s rights. This can increase the organization’s appeal in the eyes of international communities, especially those in liberal democracies. If people value gender equality, being gender-diverse would be more likely to earn groups a positive endorsement from the foreign public.

In sum, the presence of women in rebel groups can signal democratic values and gender equality, which can increase foreign public support for these groups. Although these groups are rarely democratic and rarely prioritize gender rights, gendered biases shape perceptions, helping observers interpret the conflict landscape. Media coverage and rebel outreach efforts further reinforce these associations, detailed next.

Media Coverage and Rebel Outreach: Media portrayal of female combatants can reinforce and reproduce their association with desirable ideologies and values, which can positively impact people’s perceptions. Contemporary news coverage, especially from Western media outlets, tends to corroborate rebels’ depiction of women as combating patriarchy (Nacos, Reference Nacos2005). News titles often refer to female militants as gender-equality advocates working toward emancipating suppressed women in their region. A title from The Conversation reads, “Colombian Militants Have a New Plan for the Country, and It’s Called ‘Insurgent Feminism’” (Boutron, Reference Boutron2017). Another one writes, “A ‘Utopian’ Society Promoting Gender Equality Continues to Rise from the Ashes of ISIS – Despite Turkish Attacks” and refers to Kurds’ fight in Syria as a feminist revolution (Flock, Reference Flock2024). Studies suggest that the media frames the female combatant as “exceptional, heroic, and one that deconstructs the masculinity of its adversary” (Toivanen and Baser, Reference Toivanen and Baser2016). These depictions can help organizations with women fighters be perceived as righteous by international communities, especially those concerned with liberal democratic values, even when they use violence, which is disapproved of normatively.

Rebel groups’ international outreach often aligns with media frames that emphasize women’s involvement as a sign of gender equality and empowerment. Recruiting women helps project an inclusive image that appeals to both local and international audiences. For instance, although the Irish Republican Army (IRA) initially resisted women’s participation, later pressures led to their inclusion to “demonstrate that the group represented a mass social movement” (Alison, Reference Alison2004: 454). Similarly, FARC’s recruitment of women fighters enhanced its image of inclusivity within Colombian communities (Herrera and Porch, Reference Herrera and Porch2008). The PKK underscores its commitment to gender equality by portraying women militants as the epitomes of democracy and freedom (PKK, 2023: 6). The YPJ (Women’s Defense Units of the Kurdish insurgency in Syria - Yekineyen Parastina Jin, in Kurdish) drew international attention, with visits to Rojava from global committees, intellectuals, and politicians – including French President Hollande and Swedish Defense Minister Hultqvist. The US Central Command even highlighted the public interest in female fighters in a tweet featuring them (US Central Command, 2017b).

2.2.3 Instrumental Concerns

While the humanitarian and ideological heuristics associated with women can make people more supportive of assisting rebel groups when female combatants are visibly present, instrumental concerns can push the support in a different direction. Public support for rebel groups can hinge on strategic viability, namely their perceived likelihood of succeeding in a way that would advance their country’s strategic interests. The presence of women in combat roles might signal military weakness, leading to decreased support. On the other hand, another instrumental factor, namely people’s concern for their country’s international reputation, may increase support for groups with female fighters, if people associate female fighters with pursuit of moral principles or gender equality.

First, concerns about the on-the-ground gains can reduce public support for gender-diverse rebel groups. People tend to back foreign interventions they see as likely to succeed (Eichenberg, Reference Eichenberg2005; Gelpi et al., Reference Christopher, Feaver and Reifler2009). Leaders also consider the probability of success when choosing to support armed groups, balancing this against potential security risks to their own country. The alignment between the group’s effective operations and the security interests of the sponsoring state plays a crucial role, as states are reluctant to back groups that may inadvertently create long-term security vulnerabilities (Salehyan, Gleditsch, and Cunningham, Reference Idean, Gleditsch and Cunningham2011).

Women are erroneously perceived as deficient in the attributes that are essential for success in traditionally male domains (Heilman, Reference Heilman2001). Studies demonstrate that female politicians are not perceived as tough enough for “masculinist” positions such as national security and foreign policy (Holman, Merolla, and Zechmeister, Reference Holman, Merolla and Zechmeister2011; Lawless, Reference Lawless2004). These stereotypes persist in contemporary Western and non-Western contexts, with critical implications for women’s actual political representation (Liu, Reference Liu2018). Women are mainly assigned to more “feminine” cabinet positions (Krook and O’Brien, Reference Krook and O’Brien2012) and are excluded from “masculine” positions, such as defense ministers during conflict, but are more likely to be appointed when the role becomes less conflict-centered (Barnes and O’Brien, Reference Barnes and O’Brien2018). As such, people can think that armed movements with women fighters are less likely to succeed.

Although skepticism about women’s military capabilities has declined, some mainstream outlets continue to feature headlines such as “Women Do Not Belong in Combat” (Donald, Reference Donald2019) and “Women Absolutely Do Not Belong in Combat” (Fischer, Reference Fischer2019), reflecting persistent conservative views. Recently, US Defense Minister Pete Hegseth argued against women in combat, claiming that it complicates fighting without improving effectiveness or lethality (NBC News, 2024). Similar debates appear internationally, as seen in headlines like “Female Frontline Soldiers Will Put Lives at Risk, Says Ex-Army Chief” (BBC, 2016) in the UK; “Israeli Army Debates Combat Roles for Women – With Rabbis Who Fiercely Oppose It” in Israel (Kubovich, Reference Kubovich2021); and “Kuwait Allows Women to Join Military, Igniting Debate” (Amwaj Media, Reference Media2021). These negative perspectives toward women’s military capacity can affect how people view their country’s security gains if involved in the conflict. If people view women as less capable in combat, they may equate their presence with military weakness and be less inclined to support armed groups with female insurgents, as these groups might be perceived as posing a threat to the sponsoring state’s security interests, ultimately reducing overall support.

Alternatively, people’s instrumental concerns for increasing their country’s reputation can increase support for gender-diverse groups if they associate women combatants with more righteous or gender-equal movements. Leaders and the public value their country’s reputation highly, often to the extent that decisions to use military force are driven by the desire to enhance or protect that reputation (Yarhi-Milo, Reference Yarhi-Milo2018). Just as women’s political representation can enhance an autocracy’s international reputation, women in insurgency may serve a similar function, especially among foreign publics and decision-makers who are concerned with international reputation and view gender equality as an indication of status. This is because gender equality functions as a defining norm distinguishing states perceived as civilized and reputable from those deemed uncivilized and backward (Towns, Reference Towns2010).

This reputational mechanism can be especially relevant in liberal democracies where foreign policy decisions are subject to public scrutiny and where alignment with women’s rights is deemed to be both an ideological interest and a domestic expectation. For political elites, supporting a gender-diverse rebel group allows them to frame foreign involvement not just in terms of security but also as a status-enhancing commitment to advance gender equality. For citizens, backing such groups can bolster national prestige as it aligns their state with progressive values, elevating its reputation on the global stage as a promoter of gender equality. For instance, a recent piece in Foreign Affairs argues for America’s continued hegemony in world affairs by upholding its reputation as a promoter of progressive values, and cites the alliance between the US and the SDF as an example of advancing democracy, human rights, and gender equality in the region (Stewart, Petkun, and Revkin, Reference Stewart, Petkun and Revkin2024). Sponsoring a movement led by women can be perceived as enhancing a country’s reputation in the global community, potentially garnering stronger support for these groups than they would have if they lacked women.

To sum, I organize core factors that may affect foreign audiences’ support for insurgencies in three groups, namely those focusing on: humanitarian concerns; ideologies and values; and sponsor interests. Mechanisms tied to audiences’ humanitarian concerns and values lead to favorable assessments of rebels with women: these mechanisms amplify favorable perceptions regarding reduced violence, moral conduct, democratic principles, and gender equality. Mechanisms tied to instrumental concerns may lead to either positive or negative evaluations. Perception of women as lacking capability in conflict settings may lead to reduced support for rebels with women, due to perceptions of ineffectiveness in delivering gains for the sponsoring state on the ground, namely low success likelihood or jeopardizing security interests. Conversely, audiences may believe that sponsoring rebels with women positively influences their country’s international reputation. I expect these mechanisms to impact foreign public opinions on lending foreign conflict assistance. I empirically test these expectations in the next section via original survey experiments.

3 Foreign Public Opinion toward Female Fighters: Experimental Analysis

Previous sections established that the gender composition of rebel groups can matter for public opinion and identified potential pathways through which this influence may operate. This section seeks to answer the following questions: Do foreign publics support armed movements featuring female fighters? How do they perceive these armed movements? Through what mechanisms does this support operate?

I also ask whether the perception of foreign armed movements varies systematically by citizens’ gender or gender-egalitarian attitudes. This is important because the extant research shows that women and people with more gender-egalitarian attitudes are less supportive of use of force and conflict intervention abroad compared to men and people with more gender-unequal attitudes (Wood and Ramirez, Reference Wood and Ramirez2018). This gender gap is deemed one of the most consistent findings in political psychology (Conover and Sapiro, Reference Conover and Sapiro1993); however, whether such a gap exists when the perpetrators are female has not been tested. I use survey experiments to focus on the impact of women combatants, isolating other conflict-related factors that can influence people’s support preferences, such as the country of origin or violence levels. I analyze these questions through survey experiments in the US and Tunisia.

3.1 Case Selection

The experiment is conducted over two samples: citizens of the US and of Tunisia. The US is the country engaging in foreign conflicts the most. It has a long history of providing various forms of assistance to rebel groups globally, ranging from involvement in Nicaragua, Cuba, Angola, and Iran during the Cold War, to interventions following the “global war on terror” policy in Libya and Afghanistan, to more recent engagements in Syria. These actions often sparked debates within domestic politics, where the opposition and the public have questioned the appropriateness and the consequences of supporting or terminating aid to various groups. Hence, understanding US attitudes on support for foreign conflicts is crucial in its own right and can also offer insights into the perspectives of other democratic audiences across Western nations.

Tunisia offers a valuable case with which to test the generalizability of the findings. On the one hand, like the US, Tunisia has been recognized as a democracy, hence we would expect public opinion to shape policymaking, making it a relevant comparison. The first free and fair elections were held in 2011 after Arab Spring, and a new constitution adopted in 2014 solidified the democratic framework. Tunisia was the only Arab nation classified as “free” in the 2020 Freedom House Index and was often referred to as “a democratic success story.” However, since 2021 Tunisia has been downgraded to “partially free” by Freedom House and reclassified from a “liberal democracy” to an “electoral autocracy” in V-Dem, as President Said curbed the powers of the parliament and the judiciary. This democratic backsliding raises questions about the extent to which public opinion shapes policymaking. Nonetheless, hybrid regimes like Tunisia, where democratic and authoritarian elements coexist, provide an opportunity to examine how public opinion functions within constrained democratic settings. Analyzing Tunisia helps me assess whether the findings apply beyond liberal democracies and to discuss public opinion’s role under conditions of increasing executive dominance.

In both Tunisia and the US, women constitute 16–17 percent of their state’s militaries (US Department of Defense, 2022; US Embassy in Tunisia, 2021), suggesting a similarity in people’s familiarity with women’s involvement in more masculine domains. On the other hand, Tunisia differs from the US in important ways, notably regarding military power and historical involvement in foreign conflicts, the strength of traditional gender norms, exposure to conflict, and the portrayal of female fighters in mainstream news media. These differences may lead to different attitudes toward gender-diverse groups and conflict assistance in general, representing potential challenges for the mechanisms underlined in Section 3. These make the Tunisian case informative about the extent to which the theorized mechanisms travel across contexts.

Particularly, the US has a more formally educated and high-income population where gender-progressive informal and formal institutions are more accepted, while the Tunisian population is generally more conservative. I expect that the strength of traditional gender stereotypes would be greater in Tunisia, providing a good case to test whether women’s involvement in combat creates backlashes. Further, audiences experiencing conflict in their own home country may be more hesitant to support sending conflict assistance abroad as they are more familiar with the devastating consequences of such aid. Tunisia experienced more internal conflict (such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb [AQIM] and the Islamic State–linked Jund al-Khilafah-Tunisia [JAK-T]). The US, on the other hand, while facing terrorist attacks (9/11) and intervening in Afghanistan and Iraq, has not faced persistent internal insurgencies involving organized rebel groups within its borders in recent decades.

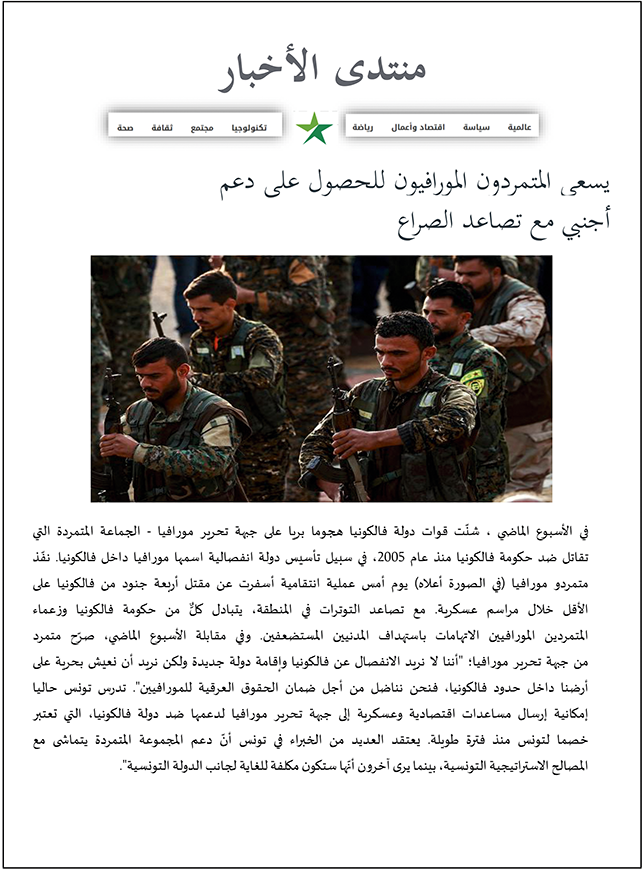

Moreover, the salience of female fighters in the mainstream media differs significantly for the US and Tunisia. The US supported the YPG (People’s Defense Units – Yekîneyên Parastina Gel, in Kurdish) against ISIS in Syria and Iraq. Numerous news stories featuring the Kurdish female fighters of the YPJ – an all-female brigade of the YPG – circulated in the US, depicting them as feminist heroines and the carriers of Western secular ideals against the radical Islamist agenda of ISIS, praising their bravery and military prowess (Yesiltas, Reference Yesiltas2022). For instance, a New York Times article title read “Women Fight ISIS and Sexism in Kurdish Regions” (Flanagin, Reference Flanagin2014). This gender dichotomy between ‘empowered YPJ’ versus ‘subjugated ISIS women’ dominated Western coverage of the Syrian war (Sjoberg, Reference Sjoberg2018).